| Part of a series on the |

| Cherokee language |

|---|

|

ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ Tsalagi Gawonihisdi |

| History |

| Grammar |

| Writing System |

| Phonology |

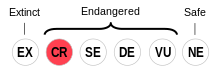

Cherokee or Tsalagi (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, romanized: Tsalagi Gawonihisdi, IPA: [dʒalaˈɡî ɡawónihisˈdî]) is an endangered-to-moribund[a] Iroquoian language[4] and the native language of the Cherokee people.[6][7][8] Ethnologue states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speakers out of 376,000 Cherokees in 2018,[4] while a tally by the three Cherokee tribes in 2019 recorded about 2,100 speakers.[5] The number of speakers is in decline. The Tahlequah Daily Press reported in 2019 that most speakers are elderly, about eight fluent speakers die each month, and that only 5 people under the age of 50 are fluent.[11] The dialect of Cherokee in Oklahoma is "definitely endangered", and the one in North Carolina is "severely endangered" according to UNESCO.[12] The Lower dialect, formerly spoken on the South Carolina–Georgia border, has been extinct since about 1900.[13] The dire situation regarding the future of the two remaining dialects prompted the Tri-Council of Cherokee tribes to declare a state of emergency in June 2019, with a call to enhance revitalization efforts.[5]

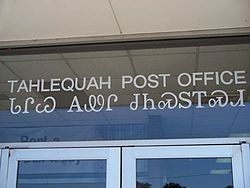

Around 200 speakers of the Eastern (also referred to as the Middle or Kituwah) dialect remain in North Carolina, and language preservation efforts include the New Kituwah Academy, a bilingual immersion school.[14] The largest remaining group of Cherokee speakers is centered around Tahlequah, Oklahoma, where the Western (Overhill or Otali) dialect predominates. The Cherokee Immersion School (Tsalagi Tsunadeloquasdi) in Tahlequah serves children in federally recognized tribes from pre-school up to grade 6.[15]

Cherokee, a polysynthetic language,[16] is also the only member of the Southern Iroquoian family,[17] and it uses a unique syllabary writing system.[18] As a polysynthetic language, Cherokee differs dramatically from Indo-European languages such as English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese, and as such can be difficult for adult learners to acquire.[6] A single Cherokee word can convey ideas that would require multiple English words to express, from the context of the assertion and connotations about the speaker to the idea's action and its object. The morphological complexity of the Cherokee language is best exhibited in verbs, which comprise approximately 75% of the language, as opposed to only 25% of the English language.[6] Verbs must contain at minimum a pronominal prefix, a verb root, an aspect suffix, and a modal suffix.[19]

Extensive documentation of the language exists, as it is the indigenous language of North America in which the most literature has been published.[20] Such publications include a Cherokee dictionary and grammar, as well as several editions of the New Testament and Psalms of the Bible[21] and the Cherokee Phoenix (ᏣᎳᎩ ᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ, Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi), the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States and the first published in a Native American language.[22][23]

Classification

Cherokee is an Iroquoian language, and the only Southern Iroquoian language spoken today. Linguists believe that the Cherokee people migrated to the southeast from the Great Lakes region[24] about three thousand years ago, bringing with them their language. Despite the three-thousand-year geographic separation, the Cherokee language today still shows some similarities to the languages spoken around the Great Lakes, such as Mohawk, Onondaga, Seneca, and Tuscarora.

Some researchers (such as Thomas Whyte) have suggested the homeland of the proto-Iroquoian language resides in Appalachia. Whyte contends, based on linguistic and molecular studies, that proto-Iroquoian speakers participated in cultural and economic exchanges along the north–south axis of the Appalachian Mountains.[citation needed] The divergence of Southern Iroquoian (which Cherokee is the only known branch of) from the Northern Iroquoian languages occurred approximately 4,000–3,000 years ago as Late Archaic proto-Iroquoian speaking peoples became more sedentary with the advent of horticulture, advancement of lithic technologies and the emergence of social complexity in the Eastern Woodlands. In the subsequent millennia, the Northern Iroquoian and Southern Iroquoian would be separated by various Algonquin and Siouan speaking peoples as linguistic, religious, social and technological practices from the Algonquin to the north and east and the Siouans to the west from the Ohio Valley would come to be practiced by peoples in the Chesapeake region, as well as parts of the Carolinas.

History

Literacy

Before the development of the Cherokee syllabary in the 1820s, Cherokee was an oral language only. The Cherokee syllabary is a set of written symbols invented by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s to write the Cherokee language. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy in that he could not previously read any script. Sequoyah had some contact with English literacy and the Roman alphabet through his proximity to Fort Loudoun, where he engaged in trade with Europeans. He was exposed to English literacy through his white father. His limited understanding of the Latin alphabet, including the ability to recognize the letters of his name, may have aided him in the creation of the Cherokee syllabary.[25] When developing the written language, Sequoyah first experimented with logograms, but his system later developed into a syllabary. In his system, each symbol represents a syllable rather than a single phoneme; the 85 (originally 86)[26] characters in the Cherokee syllabary provide a suitable method to write Cherokee. Some typeface syllables do resemble the Latin, Greek, and even the Cyrillic scripts' letters, but the sounds are completely different (for example, the sound /a/ is written with a letter that resembles Latin D).

Around 1809, Sequoyah began work to create a system of writing for the Cherokee language.[27] At first he sought to create a character for each word in the language. He spent a year on this effort, leaving his fields unplanted, so that his friends and neighbors thought he had lost his mind.[28][29] His wife is said to have burned his initial work, believing it to be witchcraft.[27] He finally realized that this approach was impractical because it would require too many pictures to be remembered. He then tried making a symbol for every idea, but this also caused too many problems to be practical.[30]

Sequoyah did not succeed until he gave up trying to represent entire words and developed a written symbol for each syllable in the language. After approximately a month, he had a system of 86 characters.[28] "In their present form, [typeface syllabary not the original handwritten Syllabary] many of the syllabary characters resemble Roman, Cyrillic, or Greek letters, or Arabic numerals," says Janine Scancarelli, a scholar of Cherokee writing, "but there is no apparent relationship between their sounds in other languages and in Cherokee."[27]

Unable to find adults willing to learn the syllabary, he taught it to his daughter, Ayokeh (also spelled Ayoka).[27] Langguth says she was only six years old at the time.[31] He traveled to the Indian Reserves in the Arkansas Territory where some Cherokees had settled. When he tried to convince the local leaders of the syllabary's usefulness, they doubted him, believing that the symbols were merely ad hoc reminders. Sequoyah asked each to say a word, which he wrote down, and then called his daughter in to read the words back. This demonstration convinced the leaders to let him teach the syllabary to a few more people. This took several months, during which it was rumored that he might be using the students for sorcery. After completing the lessons, Sequoyah wrote a dictated letter to each student, and read a dictated response. This test convinced the western Cherokees that he had created a practical writing system.[29]

When Sequoyah returned east, he brought a sealed envelope containing a written speech from one of the Arkansas Cherokee leaders. By reading this speech, he convinced the eastern Cherokees also to learn the system, after which it spread rapidly.[28][29] In 1825 the Cherokee Nation officially adopted the writing system. From 1828 to 1834, American missionaries assisted the Cherokees in using Sequoyah's original syllabary to develop typeface syllabary characters and print the Cherokee Phoenix, the first newspaper of the Cherokee Nation, with text in both Cherokee and English.[32]

In 1826, the Cherokee National Council commissioned George Lowrey and David Brown to translate and print eight copies of the laws of the Cherokee Nation in the new Cherokee language typeface using Sequoyah's system, but not his original self-created handwritten syllable glyphs.[30]

Once Albert Gallatin saw a copy of Sequoyah's syllabary, he found the syllabary superior to the English alphabet. Even though a Cherokee student must learn 86 syllables instead of 26 letters, they can read immediately. Students could accomplish in a few weeks what students of English writing could learn in two years.[31]

In 1824, the General Council of the Eastern Cherokees awarded Sequoyah a large silver medal in honor of the syllabary. According to Davis, one side of the medal bore his image surrounded by the inscription in English, "Presented to George Gist by the General Council of the Cherokee for his ingenuity in the invention of the Cherokee Alphabet." The reverse side showed two long-stemmed pipes and the same inscription written in Cherokee. Supposedly, Sequoyah wore the medal throughout the rest of his life, and it was buried with him.[30]

By 1825, the Bible and numerous religious hymns and pamphlets, educational materials, legal documents, and books were translated into the Cherokee language. Thousands of Cherokees became literate and the literacy rate for Cherokees in the original syllabary, as well as the typefaced syllabary, was higher in the Cherokee Nation than that of literacy of whites in the English alphabet in the United States.

Though use of the Cherokee syllabary declined after many of the Cherokees were forcibly removed to Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma, it has survived in private correspondence, renderings of the Bible, and descriptions of Indian medicine[33] and now can be found in books and on the internet among other places.

In February 2022, Motorola Mobility introduced a Cherokee language interface for its latest smartphone. Eastern Band Principal Chief Richard Sneed, who along with other Cherokee leaders worked with Motorola on the development, considered this an effort to preserve the language. Features included not only symbols but also the culture.[34]

Geographic distribution

The language remains concentrated in some Oklahoma communities[35] and communities like Big Cove and Snowbird in North Carolina.[36]

Dialects

At the time of European contact, there were three major dialects of Cherokee: Lower, Middle, and Overhill. The Lower dialect, formerly spoken on the South Carolina-Georgia border, has been extinct since about 1900.[13] Of the remaining two dialects, the Middle dialect (Kituwah) is spoken by the Eastern Band on the Qualla Boundary, and retains ~200 speakers.[4] The Overhill, or Western, dialect is spoken in eastern Oklahoma and by the Snowbird Community in North Carolina by ~1,300 people.[4][37] The Western dialect is most widely used and is considered the main dialect of the language.[6][38] Both dialects have had English influence, with the Overhill, or Western dialect showing some Spanish influence as well.[38]

The now extinct Lower dialect spoken by the inhabitants of the Lower Towns in the vicinity of the South Carolina–Georgia border had r as the liquid consonant in its inventory, while both the contemporary Kituhwa dialect spoken in North Carolina and the Overhill dialect contain l.

Language drift

| Drifted Otali Sequoyah syllabary mapping | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Otali syllable | Sequoyah syllabary index | Sequoyah syllabary chart | Sequoyah syllable |

| a | 00 | Ꭰ | a |

| e | 01 | Ꭱ | e |

| i | 02 | Ꭲ | i |

| o | 03 | Ꭳ | o |

| u | 04 | Ꭴ | u |

| v | 05 | Ꭵ | v |

| qwa | 06 | Ꭶ | ga |

| ka | 07 | Ꭷ | ka |

| ge | 08 | Ꭸ | ge |

| gi | 09 | Ꭹ | gi |

| go | 10 | Ꭺ | go |

| gu | 11 | Ꭻ | gu |

| gv | 12 | Ꭼ | gv |

| ha | 13 | Ꭽ | ha |

| he | 14 | Ꭾ | he |

| hi | 15 | Ꭿ | hi |

| ho | 16 | Ꮀ | ho |

| hu | 17 | Ꮁ | hu |

| hv | 18 | Ꮂ | hv |

| la | 19 | Ꮃ | la |

| le | 20 | Ꮄ | le |

| li | 21 | Ꮅ | li |

| lo | 22 | Ꮆ | lo |

| lu | 23 | Ꮇ | lu |

| lv | 24 | Ꮈ | lv |

| ma | 25 | Ꮉ | ma |

| me | 26 | Ꮊ | me |

| mi | 27 | Ꮋ | mi |

| mo | 28 | Ꮌ | mo |

| mu | 29 | Ꮍ | mu |

| na | 30 | Ꮎ | na |

| hna | 31 | Ꮏ | hna |

| nah | 32 | Ꮐ | nah |

| ne | 33 | Ꮑ | ne |

| ni | 34 | Ꮒ | ni |

| no | 35 | Ꮓ | no |

| nu | 36 | Ꮔ | nu |

| nv | 37 | Ꮕ | nv |

| qua | 38 | Ꮖ | qua |

| que | 39 | Ꮗ | que |

| qui | 40 | Ꮘ | qui |

| quo | 41 | Ꮙ | quo |

| quu | 42 | Ꮚ | quu |

| quv | 43 | Ꮛ | quv |

| sa | 44 | Ꮜ | sa |

| s | 45 | Ꮝ | s |

| se | 46 | Ꮞ | se |

| si | 47 | Ꮟ | si |

| so | 48 | Ꮠ | so |

| su | 49 | Ꮡ | su |

| sv | 50 | Ꮢ | sv |

| da | 51 | Ꮣ | da |

| ta | 52 | Ꮤ | ta |

| de | 53 | Ꮥ | de |

| te | 54 | Ꮦ | te |

| di | 55 | Ꮧ | di |

| ti | 56 | Ꮨ | ti |

| do | 57 | Ꮩ | do |

| du | 58 | Ꮪ | du |

| dv | 59 | Ꮫ | dv |

| dla | 60 | Ꮬ | dla |

| tla | 61 | Ꮭ | tla |

| tle | 62 | Ꮮ | tle |

| tli | 63 | Ꮯ | tli |

| tlo | 64 | Ꮰ | tlo |

| tlu | 65 | Ꮱ | tlu |

| tlv | 66 | Ꮲ | tlv |

| ja | 67 | Ꮳ | tsa |

| je | 68 | Ꮴ | tse |

| ji | 69 | Ꮵ | tsi |

| jo | 70 | Ꮶ | tso |

| ju | 71 | Ꮷ | tsu |

| jv | 72 | Ꮸ | tsv |

| hwa | 73 | Ꮹ | wa |

| we | 74 | Ꮺ | we |

| wi | 75 | Ꮻ | wi |

| wo | 76 | Ꮼ | wo |

| wu | 77 | Ꮽ | wu |

| wv | 78 | Ꮾ | wv |

| ya | 79 | Ꮿ | ya |

| ye | 80 | Ᏸ | ye |

| yi | 81 | Ᏹ | yi |

| yo | 82 | Ᏺ | yo |

| yu | 83 | Ᏻ | yu |

| yv | 84 | Ᏼ | yv |

There are two main dialects of Cherokee spoken by modern speakers. The Giduwa (or Kituwah) dialect (Eastern Band) and the Otali dialect (also called the Overhill dialect) spoken in Oklahoma. The Otali dialect has drifted significantly from Sequoyah's syllabary in the past 150 years, and many contracted and borrowed words have been adopted into the language. These noun and verb roots in Cherokee, however, can still be mapped to Sequoyah's syllabary. There are more than 85 syllables in use by modern Cherokee speakers.

Status and preservation efforts

In 2019, the Tri-Council of Cherokee tribes declared a state of emergency for the language due to the threat of it going extinct, calling for the enhancement of revitalization programs.[5] The language retains about 1,500[11] to 2,100[5] Cherokee speakers, but an average of eight fluent speakers die each month, and only a handful of people under 40 years of age are fluent as of 2019.[11][additional citation(s) needed] In 1986, the literacy rate for first language speakers was 15–20% who could read and 5% who could write, according to the 1986 Cherokee Heritage Center.[21] A 2005 survey determined that the Eastern Band had 460 fluent speakers. Ten years later, the number was believed to be 200.[39]

Cherokee is "definitely endangered" in Oklahoma and "severely endangered" in North Carolina according to UNESCO.[12] Cherokee has been the co-official language of the Cherokee Nation alongside English since a 1991 legislation officially proclaimed this under the Act Relating to the Tribal Policy for the Promotion and Preservation of Cherokee Language, History, and Culture.[40] Cherokee is also recognized as the official language of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. As Cherokee is official, the entire constitution of the United Keetoowah Band is available in both English and Cherokee. As an official language, any tribal member may communicate with the tribal government in Cherokee or English, English translation services are provided for Cherokee speakers, and both Cherokee and English are used when the tribe provides services, resources, and information to tribal members or when communicating with the tribal council.[40] The 1991 legislation allows the political branch of the nation to maintain Cherokee as a living language.[40] Because they are within the Cherokee Nation tribal jurisdiction area, hospitals and health centers such as the Three Rivers Health Center in Muscogee, Oklahoma provide Cherokee language translation services.[41]

Education

In 2008 the Cherokee Nation initiated a ten-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs, as well as a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at home.[42] This plan was part of an ambitious goal that in 50 years, 80 percent or more of the Cherokee people will be fluent in the language.[43] The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $4.5 million into opening schools, training teachers, and developing curricula for language education, as well as initiating community gatherings where the language can be actively used. They have accomplished: "Curriculum development, teaching materials and teacher training for a total immersion program for children, beginning when they are preschoolers, that enables them to learn Cherokee as their first language. The participating children and their parents learn to speak and read together. The Tribe operates the Kituwah Academy".[43] Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Education Program (KPEP) on the Qualla Boundary focuses on language immersion programs for children from birth to fifth grade, developing cultural resources for the general public and community language programs to foster the Cherokee language among adults.[44]

There is also a Cherokee language immersion school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that educates students from pre-school through eighth grade.[45] A second campus was added in November 2021, when the school purchased Greasy School in Greasy, Oklahoma, located in southern Adair County ten miles south of Stilwell.[46] Situated in the largest area of Cherokee speakers in the world, the opportunity for that campus is for students to spend the day in an immersion school and then return to a Cherokee-speaking home.[46]

Several universities offer Cherokee as a second language, including the University of Oklahoma, Northeastern State University, and Western Carolina University. Western Carolina University (WCU) has partnered with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) to promote and restore the language through the school's Cherokee Studies program, which offers classes in and about the language and culture of the Cherokee Indians.[47] WCU and the EBCI have initiated a ten-year language revitalization plan consisting of: (1) a continuation of the improvement and expansion of the EBCI Atse Kituwah Cherokee Language Immersion School, (2) continued development of Cherokee language learning resources, and (3) building of Western Carolina University programs to offer a more comprehensive language training curriculum.[47]

In November 2022, the tribe opened a $20 million language center in a 52,000-square-foot building near its headquarters in Tahlequah.[48] The immersion facility, which has classes for youth to adults, features no English signage: even the exit signs feature a pictograph of a person running for the door rather than the English word.[48]

The Cherokee Nation has created language lessons on the online learning platform Memrise which contain "around 1,000 Cherokee words and phrases".[49]

Phonology

The family of Iroquoian languages has a unique phonological inventory. Unlike most languages, the Cherokee inventory of consonants lacks the labial sounds /p/ and /b/. It also lacks /f/ and /v/. Cherokee does, however, have one labial consonant, /m/, but it is rare, appearing in no more than ten native words.[50] In fact, the Lower dialect does not produce /m/ at all. Instead, it uses /w/.

In the case of /p/, ⟨qw⟩ /kʷ/ is often substituted, as in the name of the Cherokee Wikipedia, Wigiqwediya. Some words may contain sounds not reflected in the given phonology: for instance, the modern Oklahoma use of the loanword "automobile", with the /ɔ/ and /b/ sounds of English.

Consonants

As with many Iroquoian languages, Cherokee's phonemic inventory is small. The consonants for North Carolina Cherokee are given in the table below. The consonants of all Iroquoian languages pattern so that they may be grouped as (oral) obstruents, sibilants, laryngeals, and resonants.[51]: 337

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | plain | labial | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Stop | t | k | kʷ | ʔ | |||

| Affricate | t͡s | t͡ɬ | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | ɰ | ||||

Notes

- The stops /t, k, kʷ/ and affricates /t͡s, t͡ɬ/ are voiced in the beginning of syllables and between vowels: [d, g, gʷ, d͡z, d͡ɮ]. Before /h/, they surface as aspirated stops: [tʰ, kʰ, kʷʰ, t͡sʰ], except /t͡ɬ/ which surfaces as a plain voiceless affricate [t͡ɬ] or fricative [ɬ] in some Oklahoma Cherokee speakers.[52][53] These aspirated allophones are felt as separate phonemes by native speakers and are often reflected as such in the orthographies (in romanization or syllabary).

- /t͡s/ is palatalized as [t͡ɕ ⁓ t͡ʃ] (voiced allophones: [d͡ʑ ⁓ d͡ʒ]) in the Oklahoma dialects,[54] but [t͡s] before /h/ + obstruent after vowel deletion:[55] jⱥ-hdlv́vga becomes tsdlv́vga 'you are sick'.[56]

- /t͡ɬ/ has merged with /t͡s/ in most North Carolina dialects.[52]

- [g] (the voiced allophone of /k/) can also be lenited to [ɣ], and [gʷ] (the voiced allophone of /kʷ/) to [ɣʷ ⁓ w].[57][58]

- The sonorants /n, l, j, ɰ/ are devoiced when preceding or following /h/, with varying degrees of allophony: [n̥, l̥⁓ɬ, j̥⁓ç, w̥⁓ʍ⁓ɸ].[59]

- /m/ is the only true labial. It occurs only in a dozen native words[60] and is not reconstructed for Proto-Iroquoian.[61]

- /s/ is realized as [ʃ] or even [ʂ] in North Carolina dialects. After a short vowel, /s/ is always preceded by a faint /h/, generally not spelled in the romanized orthographies.[59][62][55]

- /ʔ/ and /h/, including the pre-aspiration /h/ mentioned above, participate in complex rules of laryngeal and tonal alternations, often surfacing as various tones instead. Ex: h-vhd-a > hvhda "use it!" but g-vhd-íha > gvv̀díha "I am using it" with a low falling tone;[60] wi-hi-gaht-i > hwikti "you're heading there" but wi-ji-gaht-i > wijigáati "I am heading there" with a falling tone.

Orthography

There are two main competing orthographies, depending on how plain and aspirated stops (including affricates) are represented:[63][64][65]

- In the d/t system, plain stops are represented by English voiced stops (d, g, gw, j, dl) and aspirated stops by English voiceless stops (t, k, kw, c, tl). This orthography is favored by native speakers.

- In the t/th system, plain stops are represented by voiceless stops instead, and aspirated stops by sequences of voiceless stops + h (th, kh, khw/kwh, ch, thl/tlh). This orthography is favored by linguists.

Another orthography, used in Holmes (1977), doesn't distinguish plain stops from aspirated stops for /t͡sa/ and /kw/ and uses ts and qu for both modes.[66] Spellings working from the syllabary rather than from the sounds often behave similarly, /t͡s/ and /kʷ/ being the only two stop series not having separate letters for plain and aspirated before any vowel in Sequoyah script. Ex: ᏌᏊ saquu [saàgʷu], ᏆᎾ quana [kʷʰana].

Vowels

There are six short vowels and six long vowels in the Cherokee inventory.[67] As with all Iroquoian languages, this includes a nasalized vowel.[51]: 337 In the case of Cherokee, the nasalized vowel is a mid central vowel usually represented as v and is pronounced [ə̃], that is as a schwa vowel like the unstressed "a" in the English word "comma" plus the nasalization. It is similar to the nasalized vowel in the French word un which means "one".

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | ə̃ ə̃ː | o oː |

| Open | a aː |

/u/ is weakly rounded and often realized as [ɯ ⁓ ʉ].

Word-final vowels are short and nasalized, and receive an automatic high or high-falling tone: wado [wadṍ] 'thank you'.[68] They are often dropped in casual speech: gaáda [gaátʰ] 'dirt'.[69] When deletion happens, trailing /ʔ/ and /h/ are also deleted and any resulting long vowel is further shortened:[70] uùgoohvv́ʔi becomes uùgoohv́ 'he saw it'.

Short vowels are devoiced before /h/: digadóhdi [digadó̥hdĩ́].[68] But due to the phonological rules of vowel deletion, laryngeal metathesis and laryngeal alternation (see below), this environment is relatively rare.

Sequences of two non-identical vowels are disallowed and the vowel clash must be resolved. There are four strategies depending on the phonological and morphological environments:[71]

- the first vowel is kept: uù-aduulíha becomes uùduulíha 'he wants',

- the second vowel is kept: hi-ééga becomes hééga 'you're going',

- an epenthetic consonant is inserted: jii-uudalééʔa becomes jiiyuudalééʔa,

- they merge into a different vowel or tone quality.

These make the identification of each individual morpheme often a difficult task:

dee-

DIST-

ii-

ITER-

uu-

3B-

adaa(d)-

REFL-

nv́vneel

give:PFV

-vv́ʔi

-EXP

"he gave them right back to him"

dee-

DIST-

iinii-

1A.DU-

asuúléésg

wash.hands:IPFV

-o

-HAB

"you and I always wash our hands"

Tone

Cherokee distinguishes six pitch patterns or tones, using four pitch levels. Two tones are level (low, high) and appear on short or long vowels. The other four are contour tones (rising, falling, lowfall, highrise) and appear on long vowels only.[72]

There is no academic consensus on the notation of tone and length, although in 2011 a project began to document the use of tones in Cherokee to improve language instruction.[73] Below are the main conventions, along with the standardized IPA notation.

| Vowel length | Tone | IPA | Pulte & Feeling (1975) |

Scancarelli (1986) |

Montgomery-Anderson (2008, 2015) |

Feeling (2003), Uchihara (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | Low | ˨ | ạ² | à | a | a |

| High | ˧ | ạ³ | á | á | á | |

| Long | Low | ˨ | a² | à: | aa | aa |

| High | ˧ | a³ | á: | áa | áá | |

| Rising | ˨˧ | a²³ | ǎ: | aá | aá | |

| Falling | ˧˨ | a³² | â: | áà | áà | |

| Lowfall | ˨˩ | a¹ (= a²¹) | ȁ: | aà | àà, àa | |

| Superhigh | ˧˦ | a⁴ (= a³⁴) | a̋: | áá | aa̋ |

- The low tone is the default, unmarked tone.

- The high tone is the marked tone. Some sources of high tone apply to the mora, others to the syllable. Complex morphophonological rules govern whether it can spread one mora to the left, to the right or at all. It has both lexical and morphological functions.

- The rising and falling tones are secondary tones, i.e. combinations of low and high tones, deriving from moraic high tones and from high tone spread.

- The lowfall tone mainly derives from glottal stop deletion after a long vowel, but also has important morphological functions (pronominal lowering, tonic/atonic alternation, laryngeal alternation).

- The superhigh tone, also called highfall by Montgomery-Anderson, has a distinctive morphosyntactical function, primarily appearing on adjectives, nouns derived from verbs, and on subordinate verbs. It is mobile and falls on the rightmost long vowel. If the final short vowel is dropped and the superhigh tone becomes in word-final position, it is shortened and pronounced like a slightly higher final tone (notated as a̋ in most orthographies). There can only be one superhigh tone per word, constraint not shared by the other tones. For these reasons, this contour exhibits some accentual properties and has been referred to as an accent (or stress) in the literature.[74]

While the tonal system is undergoing a gradual simplification in many areas, it remains important in meaning and is still held strongly by many, especially older, speakers. The syllabary displays neither tone nor vowel length, but as stated earlier regarding the paucity of minimal pairs, real cases of ambiguity are rare. The same goes for transliterated Cherokee (osiyo for [oosíjo], dohitsu for [doòhiı̋dʒu], etc.), which is rarely written with any tone markers, except in dictionaries. Native speakers can tell the difference between written words based solely on context.

Grammar

Cherokee, like many Native American languages, is polysynthetic, meaning that many morphemes may be linked together to form a single word, which may be of great length. Cherokee verbs must contain at a minimum a pronominal prefix, a verb root, an aspect suffix, and a modal suffix,[19] for a total of 17 verb tenses.[39] They can also bear prepronominal prefixes, reflexive prefixes, and derivational suffixes. Given all possible combinations of affixes, each regular verb can have 21,262 inflected forms.

For example, the verb form gééga, 'I am going', has each of these elements:

| Ꭸ | Ꭶ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| g- | -éé- | -g- | -a |

| PRONOMINAL PREFIX 1 sg |

VERB ROOT 'to go' |

ASPECT SUFFIX present |

MODAL SUFFIX |

The pronominal prefix is g-, which indicates first person singular. The verb root is -éé-, 'to go.' The aspect suffix that this verb employs for the present-tense stem is -g-. The present-tense modal suffix for regular verbs in Cherokee is -a.

Cherokee makes three number distinctions on pronouns: singular, dual and plural. It does not make gender distinction,[75] but does distinguish animacy in third person pronouns. Cherokee also makes the distinction between inclusive and exclusive pronouns in the first person dual and plural. There is no distinction between dual and plural in the 3rd person. This makes a total of 10 persons.

The following is the conjugation of this verb form in all 10 persons.[76]

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | exclusive | ᎨᎦ (ge-ga) gééga I'm going |

ᎣᏍᏕᎦ (o-s-de-ga) oòsdééga We two (not you) are going |

ᎣᏤᎦ (o-tse-ga) oòjééga We're (not you) all going |

| inclusive | ᎢᏁᎦ (i-ne-ga) iìnééga You & I are going |

ᎢᏕᎦ iìdééga We're (& you) all going | ||

| 2nd | ᎮᎦ (he-ga) hééga You're going |

ᏍᏕᎦ (s-de-ga) sdééga You two are going |

ᎢᏤᎦ (i-tse-ga) iìjééga You're all going | |

| 3rd | ᎡᎦ (e-ga) ééga She/he/it's going |

ᎠᏁᎦ (a-ne-ga) aànééga They are going | ||

The translation uses the present progressive ('at this time I am going'). Cherokee differentiates between progressive ('I am going') and habitual ('I go') more than English does. For the habitual, the aspectual prefix is -g- "imperfective" or "incompletive" (here identical to present, but can vary for other verbs) and the modal prefix -óóʼi "habitual".

| Person | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | exclusive | ᎨᎪᎢ (ge-go-i) géégóóʼi I often/usually go |

ᎣᏍᏕᎪᎢ (o-s-de-go-i) oòsdéégóóʼi We two (not you) often/usually go |

ᎣᏤᎪᎢ (o-tse-go-i) oòjéégóóʼi We (not you) often/usually go |

| inclusive | ᎢᏁᎪᎢ (i-ne-go-i) iìnéégóóʼi You & I often/usually go |

ᎢᏕᎪᎢ (i-de-go-i) iìdéégóóʼi We (& you) often/usually go | ||

| 2nd | ᎮᎪᎢ (he-go-i) héégóóʼi You often/usually go |

ᏍᏕᎪᎢ (s-de-go-i) sdéégóóʼi You two often/usually go |

ᎢᏤᎪᎢ (i-tse-go-i) iìjéégóóʼi You often/usually go | |

| 3rd | ᎡᎪᎢ (e-go-i) éégóóʼi She/he/it often/usually goes |

ᎠᏁᎪᎢ (a-ne-go-i) aànéégóóʼi They often/usually go | ||

Pronouns and pronominal prefixes

Like many Native American languages, Cherokee has many pronominal prefixes that can index both subject and object. Pronominal prefixes always appear on verbs and can also appear on adjectives and nouns.[77] There are two separate words which function as pronouns: aya 'I, me' and nihi 'you'.

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| set I | set II | set I | set II | set I | set II | ||

| singular | ji-, g- | agi-, agw- | hi-, h- | ja-, j- | ga/a-, X- | u-, X- | |

| dual | inclusive | ini-, in- | gini-, gin- | sdi-, sd- | desdi-, desd- | – | – |

| exclusive | osdi-, osd- | ogini-, ogin- | – | – | – | – | |

| plural | inclusive | idi-, id- | igi-, ig- | iji-, ij- | deji-, dej- | – | – |

| exclusive | oji-, oj- | ogi-, og- | – | – | ani-, an- | uni, un- | |

Compound pronouns

A Cherokee pronoun's number marks not only the agent of a verb, but often the object as well. This is the case if the depending object was already mentioned and would be substituted by a separate pronoun in English as well. Contrary to English, animacy is marked but gender is not.

(These suffixes have to be treated in a CV syllabary structure.) Set I and II join here except if written A | B.

Object Subject

|

1 s | 2 s | 3 s an | 3 s in | 1 d inc | 1 d exc | 2 d | 1 p inc | 1 p exc | 2 p | 3 p an | 3 p in |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 singular | – | gv(y)- | ji(y)- | g(e)- | – | – | sdv(y)- | – | – | ijv(y)- | gaji(y)- | deg(a)- |

| 2 singular | sg(w)(i)- | – | hi(y)- | h(i)- | – | sgini(y)- | – | – | isgi(y)- | – | gahi(y)- | deh(i)- |

| 3 singular (animate) | agw(a)- | j(i)- | g(i)- | g(i)- | gin(i)- | ogin(i)- | sd(i)- | ig(i)- | og(i)- | ij(i)- | deg(i)- | deg(i)- |

| 1 dual inclusive | – | – | en(i)- | in(i)- | – | – | – | – | – | – | gen(i)- | den(i)- |

| 1 dual exclusive | – | sdv(y)- | osd(i)- | osd(i)- | – | – | sdv(y)- | – | – | ijv(y)- | gosd(i)- | dosd(i)- |

| 2 dual | sgin(i)- | – | esd(i) | sd(i)- | – | sgin(i)- | – | – | isgi(y)- | – | gesd(i)- | desd(i)- |

| 1 plural inclusive | – | – | ed(i)- | id(i)- | – | – | – | – | – | – | ged(i)- | ded(i)- |

| 1 plural exclusive | – | ijv(y)- | oj(i)- | oj(i)- | – | – | ijv(y)- | – | – | ijv(y)- | goj(i)- | doj(i)- |

| 2 plural | isgi(y)- | – | ej(i)- | ij(i)- | – | isgi(y)- | – | – | isgi(y)- | – | gej(i)- | dej(i)- |

| 3 plural (animate) | gvg(w)(i)- | gej(i)- | an(i)- | un(i)- | an(i)- | un(i)- | gegin(i)- | gogin(i)- | gesd(i)- | geg(i)- | gog(i)- | gej(i)- | gan(i)- | gun(i)- | dan(i)- | dun(i)- |

Some prefixes are the same, even though they mean their opposite. Understanding is ensured by regular stem changes within the verb.

Shape classifiers in verbs

Some Cherokee verbs require special classifiers which denote a physical property of the direct object. Only around 20 common verbs require one of these classifiers (such as the equivalents of 'pick up', 'put down', 'remove', 'wash', 'hide', 'eat', 'drag', 'have', 'hold', 'put in water', 'put in fire', 'hang up', 'be placed', 'pull along'). The classifiers can be grouped into five categories:

- Live

- Flexible (most common)

- Long (narrow, not flexible)

- Indefinite (solid, heavy relative to size), also used as default category[78]

- Liquid (or container of)

Example:

| Classifier type | Cherokee | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live | ᎯᎧᏏ | hikasi | Hand him (something living) |

| Flexible | ᎯᏅᏏ | hinvsi | Hand him (something like clothes, rope) |

| Long, indefinite | ᎯᏗᏏ | hidisi | Hand him (something like a broom, pencil) |

| Indefinite | ᎯᎥᏏ | hivsi | Hand him (something like food, book) |

| Liquid | ᎯᏁᎥᏏ | hinevsi | Hand him (something like water) |

There have been reports that the youngest speakers of Cherokee are using only the indefinite forms, suggesting a decline in usage or full acquisition of the system of shape classification.[13] Cherokee is the only Iroquoian language with this type of classificatory verb system, leading linguists to reanalyze it as a potential remnant of a noun incorporation system in Proto-Iroquoian.[79] However, given the non-productive nature of noun incorporation in Cherokee, other linguists have suggested that classificatory verbs are the product of historical contact between Cherokee and non-Iroquoian languages, and instead that the noun incorporation system in Northern Iroquoian languages developed later.[80]

Word order

All orderings between subjects, verbs, and objects are possible in Cherokee sentences, but word order preferences are influenced by a number of factors. Some preferences are determined by information structure; items that express new information typically precede those that refer to entities already in the conversation.[81] Word order is also influenced by thematic role, such that agent arguments of transitive sentences (subjects) typically precede theme arguments (objects).[82][83] In copular sentences, the subject complement must precede the copular verb.[84] Negative sentences have a different word order.[citation needed]

Adjectives precede nouns, as in English. Demonstratives, such as ᎾᏍᎩ nasgi ('that') or ᎯᎠ hia ('this'), come at the beginning of noun phrases. Relative clauses follow noun phrases.[82] Adverbs precede the verbs that they are modifying. For example, 'she's speaking loudly' is ᎠᏍᏓᏯ ᎦᏬᏂᎭ asdaya gawoniha (literally, 'loud she's-speaking').[82]

In affirmative present tense sentences, no verb is required to express a copular, predicative relationship between two noun phrases. In such a case, word order is flexible. For example, Ꮎ ᎠᏍᎦᏯ ᎠᎩᏙᏓ na asgaya agidoda ('that man is my father'). A noun phrase might be followed by an adjective, such as in ᎠᎩᏙᏓ ᎤᏔᎾ agidoda utana ('my father is big').[85]

Orthography

Cherokee is written in an 85-character syllabary invented by Sequoyah (also known as Guest or George Gist). Many of the letters resemble the Latin letters they derive from, but have completely unrelated sound values; Sequoyah had seen English, Hebrew, and Greek writing but did not know how to read them.[86]

Two other scripts used to write Cherokee are a simple Latin transliteration and a more precise system with Diacritical marks.[87]

Description

Each of the characters represents one syllable, as in the Japanese kana and the Bronze Age Greek Linear B writing systems. The first six characters represent isolated vowel syllables. Characters for combined consonant and vowel syllables then follow. It is recited from left to right, top to bottom.[88][page needed]

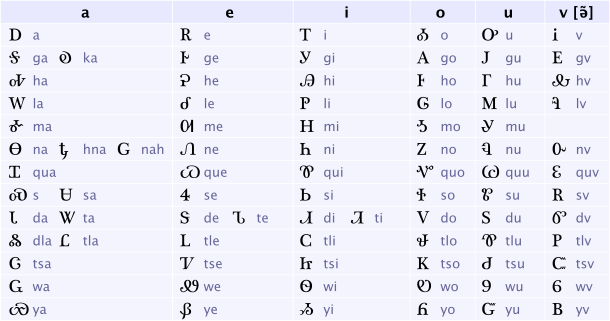

The charts below show the syllabary as arranged by Samuel Worcester along with his commonly used transliterations. He played a key role in the development of Cherokee printing from 1828 until his death in 1859.

Notes

- In the chart, 'v' represents a nasal vowel, /ə̃/.

- The character Ꮩ do is shown upside-down in some fonts.[b]

The transliteration working from the syllabary uses conventional consonants like qu and ts, and may differ from the ones used in the phonological orthographies (first column in the below chart, in the d/t system).

| Ø | Ꭰ | Ꭱ | Ꭲ | Ꭳ | Ꭴ | Ꭵ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g / k | Ꭶ | Ꭷ | Ꭸ | Ꭹ | Ꭺ | Ꭻ | Ꭼ | ||||||||

| h | Ꭽ | Ꭾ | Ꭿ | Ꮀ | Ꮁ | Ꮂ | |||||||||

| l / hl | Ꮃ | Ꮄ | Ꮅ | Ꮆ | Ꮇ | Ꮈ | |||||||||

| m | Ꮉ | Ꮊ | Ꮋ | Ꮌ | Ꮍ | ||||||||||

| n / hn | Ꮎ | Ꮏ | Ꮐ | Ꮑ | Ꮒ | Ꮓ | Ꮔ | Ꮕ | |||||||

| gw / kw | Ꮖ | Ꮗ | Ꮘ | Ꮙ | Ꮚ | Ꮛ | |||||||||

| s | Ꮝ | Ꮜ | Ꮞ | Ꮟ | Ꮠ | Ꮡ | Ꮢ | ||||||||

| d / t | Ꮣ | Ꮤ | Ꮥ | Ꮦ | Ꮧ | Ꮨ | Ꮩ | Ꮪ | Ꮫ | ||||||

| dl / tl (hl) | Ꮬ | Ꮭ | Ꮮ | Ꮯ | Ꮰ | Ꮱ | Ꮲ | ||||||||

| j / c (dz / ts) |

Ꮳ | Ꮴ | Ꮵ | Ꮶ | Ꮷ | Ꮸ | |||||||||

| w / hw | Ꮹ | Ꮺ | Ꮻ | Ꮼ | Ꮽ | Ꮾ | |||||||||

| y / hy | Ꮿ | Ᏸ | Ᏹ | Ᏺ | Ᏻ | Ᏼ | |||||||||

The phonetic values of these characters do not equate directly to those represented by the letters of the Latin script. Some characters represent two distinct phonetic values (actually heard as different syllables), while others often represent different forms of the same syllable.[88][page needed] Not all phonemic distinctions of the spoken language are represented:

- Aspirated consonants are generally not distinguished from their plain counterpart. For example, while /d/ + vowel syllables are mostly differentiated from /t/ + vowel by use of different glyphs, syllables beginning with /ɡw/ are all conflated with those beginning with /kw/.

- Long vowels are not distinguished from short vowels. However, in more recent technical literature, length of vowels can actually be indicated using a colon, and other disambiguation methods for consonants (somewhat like the Japanese dakuten) have been suggested.

- Tones are not marked.

- Syllables ending in vowels, h, or glottal stop are undifferentiated. For example, the single symbol Ꮡ is used to represent both suú as in suúdáli, meaning 'six' (ᏑᏓᎵ), and súh as in súhdi, meaning 'fishhook' (ᏑᏗ).

- There is no regular rule for representing consonant clusters. When consonants other than s, h, or glottal stop arise in clusters with other consonants, a vowel must be inserted, chosen either arbitrarily or for etymological reasons (reflecting an underlying etymological vowel, see vowel deletion for instance). For example, ᏧᎾᏍᏗ (tsu-na-s-di) represents the word juunsdi̋, meaning 'small (pl.), babies'. The consonant cluster ns is broken down by insertion of the vowel a, and is spelled as ᎾᏍ /nas/. The vowel is etymological as juunsdi̋ is composed of the morphemes di-uunii-asdii̋ʔi (DIST-3B.pl-small), where a is part of the root. The vowel is included in the transliteration, but is not pronounced.

As with some other underspecified writing systems, such as Arabic, adult speakers can distinguish words by context.

Transliteration issues

Transliteration software that operates without access to or reference to context greater than a single character can have difficulties with some Cherokee words. For example, words that contain adjacent pairs of single letter symbols, that (without special provisions) would be combined when doing the back conversion from Latin script to Cherokee. Here are a few examples:

Ꭲ

i-

Ꮳ

tsa-

Ꮅ

li-

Ꮝ

s-

Ꭰ

a-

Ꮑ

ne-

Ꮧ

di

itsalisanedi

Ꭴ

u-

Ꮅ

li-

Ꭹ

gi-

Ᏻ

yu-

Ꮝ

s-

Ꭰ

a-

Ꮕ

nv-

Ꮑ

ne

uligiyusanvne

Ꭴ

u-

Ꮒ

ni-

Ᏸ

ye-

Ꮝ

s-

Ꭲ

i-

Ᏹ

yi

uniyesiyi

Ꮎ

na-

Ꮝ

s-

Ꭲ

i-

Ꮿ

ya

nasiya

For these examples, the back conversion is likely to join s-a as sa or s-i as si. Transliterations sometimes insert an apostrophe to prevent this, producing itsalis'anedi (cf. Man'yōshū).

Other Cherokee words contain character pairs that entail overlapping transliteration sequences. Examples:

- ᏀᎾ transliterates as nahna, yet so does ᎾᎿ. The former is nah-na, the latter is na-hna.

If the Latin script is parsed from left to right, longest match first, then without special provisions, the back conversion would be wrong for the latter. There are several similar examples involving these character combinations: naha nahe nahi naho nahu nahv.

A further problem encountered in transliterating Cherokee is that there are some pairs of different Cherokee words that transliterate to the same word in the Latin script. For example, ᎠᏍᎡᏃ and ᎠᏎᏃ both transliterate to aseno, and ᎨᏍᎥᎢ and ᎨᏒᎢ both transliterate to gesvi. Without special provision, a round-trip conversion changes ᎠᏍᎡᏃ to ᎠᏎᏃ and changes ᎨᏍᎥᎢ to ᎨᏒᎢ.[c]

Unicode

Cherokee was added to the Unicode Standard in September 1999 with the release of version 3.0.

Blocks

The main Unicode block for Cherokee is U+13A0–U+13FF.[d] It contains the script's upper-case syllables as well as six lower-case syllables:

| Cherokee[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+13Ax | Ꭰ | Ꭱ | Ꭲ | Ꭳ | Ꭴ | Ꭵ | Ꭶ | Ꭷ | Ꭸ | Ꭹ | Ꭺ | Ꭻ | Ꭼ | Ꭽ | Ꭾ | Ꭿ |

| U+13Bx | Ꮀ | Ꮁ | Ꮂ | Ꮃ | Ꮄ | Ꮅ | Ꮆ | Ꮇ | Ꮈ | Ꮉ | Ꮊ | Ꮋ | Ꮌ | Ꮍ | Ꮎ | Ꮏ |

| U+13Cx | Ꮐ | Ꮑ | Ꮒ | Ꮓ | Ꮔ | Ꮕ | Ꮖ | Ꮗ | Ꮘ | Ꮙ | Ꮚ | Ꮛ | Ꮜ | Ꮝ | Ꮞ | Ꮟ |

| U+13Dx | Ꮠ | Ꮡ | Ꮢ | Ꮣ | Ꮤ | Ꮥ | Ꮦ | Ꮧ | Ꮨ | Ꮩ | Ꮪ | Ꮫ | Ꮬ | Ꮭ | Ꮮ | Ꮯ |

| U+13Ex | Ꮰ | Ꮱ | Ꮲ | Ꮳ | Ꮴ | Ꮵ | Ꮶ | Ꮷ | Ꮸ | Ꮹ | Ꮺ | Ꮻ | Ꮼ | Ꮽ | Ꮾ | Ꮿ |

| U+13Fx | Ᏸ | Ᏹ | Ᏺ | Ᏻ | Ᏼ | Ᏽ | ᏸ | ᏹ | ᏺ | ᏻ | ᏼ | ᏽ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The rest of the lower-case syllables are encoded at U+AB70–ABBF:

| Cherokee Supplement[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+AB7x | ꭰ | ꭱ | ꭲ | ꭳ | ꭴ | ꭵ | ꭶ | ꭷ | ꭸ | ꭹ | ꭺ | ꭻ | ꭼ | ꭽ | ꭾ | ꭿ |

| U+AB8x | ꮀ | ꮁ | ꮂ | ꮃ | ꮄ | ꮅ | ꮆ | ꮇ | ꮈ | ꮉ | ꮊ | ꮋ | ꮌ | ꮍ | ꮎ | ꮏ |

| U+AB9x | ꮐ | ꮑ | ꮒ | ꮓ | ꮔ | ꮕ | ꮖ | ꮗ | ꮘ | ꮙ | ꮚ | ꮛ | ꮜ | ꮝ | ꮞ | ꮟ |

| U+ABAx | ꮠ | ꮡ | ꮢ | ꮣ | ꮤ | ꮥ | ꮦ | ꮧ | ꮨ | ꮩ | ꮪ | ꮫ | ꮬ | ꮭ | ꮮ | ꮯ |

| U+ABBx | ꮰ | ꮱ | ꮲ | ꮳ | ꮴ | ꮵ | ꮶ | ꮷ | ꮸ | ꮹ | ꮺ | ꮻ | ꮼ | ꮽ | ꮾ | ꮿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Fonts and digital platform support

A single Cherokee Unicode font, Plantagenet Cherokee, is supplied with macOS, version 10.3 (Panther) and later. Windows Vista also includes a Cherokee font. Several free Cherokee fonts are available including Digohweli, Donisiladv, and Noto Sans Cherokee. Some pan-Unicode fonts, such as Code2000, Everson Mono, and GNU FreeFont, include Cherokee characters. A commercial font, Phoreus Cherokee, published by TypeCulture, includes multiple weights and styles.[90] The Cherokee Nation Language Technology Program supports "innovative solutions for the Cherokee language on all digital platforms including smartphones, laptops, desktops, tablets and social networks."[91]

Vocabulary

Numbers

Cherokee uses Arabic numerals (0–9). The Cherokee council voted not to adopt Sequoyah's numbering system.[92] Sequoyah created individual symbols for 1–20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 as well as a symbol for three zeros for numbers in the thousands, and a symbol for six zeros for numbers in the millions. These last two symbols, representing ",000" and ",000,000", are made up of two separate symbols each. They have a symbol in common, which could be used as a zero in itself.

| English | Cherokee[93] | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| one | ᏌᏊ | saquu |

| two | ᏔᎵ | tali |

| three | ᏦᎢ | tsoi |

| four | ᏅᎩ | nvgi |

| five | ᎯᏍᎩ | hisgi |

| six | ᏑᏓᎵ | sudali |

| seven | ᎦᎵᏉᎩ | galiquogi |

| eight | ᏧᏁᎳ | tsunela |

| nine | ᏐᏁᎳ | sonela |

| ten | ᏍᎪᎯ | sgohi |

| eleven | ᏌᏚ | sadu |

| twelve | ᏔᎵᏚ | talidu |

| thirteen | ᏦᎦᏚ | tsogadu |

| fourteen | ᏂᎦᏚ | nigadu |

| fifteen | ᎯᏍᎦᏚ | hisgadu |

| sixteen | ᏓᎳᏚ | daladu |

| seventeen | ᎦᎵᏆᏚ | galiquadu |

| eighteen | ᏁᎳᏚ | neladu |

| nineteen | ᏐᏁᎳᏚ | soneladu |

| twenty | ᏔᎵᏍᎪᎯ | talisgohi |

Days

| English | Cherokee[93][94] | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| Days of the week | ᎯᎸᏍᎩᎢᎦ | hilvsgiiga |

| Sunday | ᎤᎾᏙᏓᏆᏍᎬ | unadodaquasgv |

| Monday | ᎤᎾᏙᏓᏉᏅᎯ | unadodaquohnvhi |

| Tuesday | ᏔᎵᏁᎢᎦ | talineiga |

| Wednesday | ᏦᎢᏁᎢᎦ | tsoineiga |

| Thursday | ᏅᎩᏁᎢᎦ | nvgineiga |

| Friday | ᏧᎾᎩᎶᏍᏗ | junagilosdi |

| Saturday | ᎤᎾᏙᏓᏈᏕᎾ | unadodaquidena |

Months

| English | Meaning | Cherokee | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | Month of the Cold Moon | ᏚᏃᎸᏔᏂ | dunolvtani |

| February | Month of the Bony Moon | ᎧᎦᎵ | kagali |

| March | Month of the Windy Moon | ᎠᏄᏱ | anuyi |

| April | Month of the Flower Moon | ᎧᏩᏂ | kawani |

| May | Month of the Planting Moon | ᎠᎾᎠᎬᏘ | anaagvti |

| June | Month of the Green Corn Moon | ᏕᎭᎷᏱ | dehaluyi |

| July | Month of the Ripe Corn Moon | ᎫᏰᏉᏂ | guyequoni |

| August | Month of the End of Fruit Moon | ᎦᎶᏂᎢ | galonii |

| September | Month of the Nut Moon | ᏚᎵᎢᏍᏗ | duliisdi |

| October | Month of the Harvest Moon | ᏚᏂᏅᏗ | duninvdi |

| November | Month of Trading Moon | ᏄᏓᏕᏆ | nudadequa |

| December | Month of the Snow Moon | ᎥᏍᎩᎦ | vsgiga |

Colors

| English | Cherokee | Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| black | ᎬᎾᎨᎢ | gvnagei |

| blue | ᏌᎪᏂᎨᎢ | sagonigei |

| brown | ᎤᏬᏗᎨ | uwodige |

| green | ᎢᏤᎢᏳᏍᏗ | itseiyusdi |

| gray | ᎤᏍᎪᎸ ᏌᎪᏂᎨ | usgolv sagonige |

| gold | ᏓᎶᏂᎨᎢ | dalonigei |

| orange | ᎠᏌᎶᏂᎨ | asalonige |

| pink | ᎩᎦᎨᎢᏳᏍᏗ | gigageiyusdi |

| purple | ᎩᎨᏍᏗ | gigesdi |

| red | ᎩᎦᎨ | gigage |

| silver | ᎠᏕᎸ ᎤᏁᎬ | adelv unegv |

| white | ᎤᏁᎦ | unega |

| yellow | ᏓᎶᏂᎨ | dalonige |

Word creation

The polysynthetic nature of the Cherokee language enables the language to develop new descriptive words in Cherokee to reflect or express new concepts. Some good examples are ᏗᏘᏲᎯᎯ (ditiyohihi, 'he argues repeatedly and on purpose with a purpose') corresponding to 'attorney' and ᏗᏓᏂᏱᏍᎩ (didaniyisgi, 'the final catcher' or 'he catches them finally and conclusively') for 'policeman'.[95]

Other words have been adopted from another language such as the English word gasoline, which in Cherokee is ᎦᏐᎵᏁ (gasoline). Other words were adopted from the languages of tribes who settled in Oklahoma in the early 1900s. One interesting and humorous example is the name of Nowata, Oklahoma, deriving from nowata, a Delaware word for 'welcome' (more precisely the Delaware word is nuwita which can mean 'welcome' or 'friend' in the Delaware languages). The white settlers of the area used the name Nowata for the township, and local Cherokee, being unaware that the word had its origins in the Delaware language, called the town ᎠᎹᏗᎧᏂᎬᎾᎬᎾ (Amadikanigvnagvna) which means 'the water is all gone gone from here' — i.e. 'no water'.[96]

Other examples of adopted words are ᎧᏫ (kawi) for 'coffee' and ᏩᏥ (watsi) for 'watch'; which led to ᎤᏔᎾ ᏩᏥ (utana watsi, 'big watch') for clock.[96]

Meaning expansion can be illustrated by the words for 'warm' and 'cold', which can be also extended to mean 'south' and 'north'. Around the time of the American Civil War, they were further extended to US party labels, Democratic and Republican, respectively.[97]

Samples

From the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

ᏂᎦᏓ ᎠᏂᏴᏫ ᏂᎨᎫᏓᎸᎾ ᎠᎴ ᎤᏂᎶᏱ ᎤᎾᏕᎿ ᏚᏳᎧᏛ ᎨᏒᎢ.

Nigada aniyvwi nigeguda'lvna ale unihloyi unadehna duyukdv gesv'i.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

ᎨᏥᏁᎳ ᎤᎾᏓᏅᏖᏗ ᎠᎴ ᎤᏃᎵᏍᏗ

Gejinela unadanvtehdi ale unohlisdi

They are endowed with reason and conscience

ᎠᎴ ᏌᏊ ᎨᏒ ᏧᏂᎸᏫᏍᏓᏁᏗ ᎠᎾᏟᏅᏢ ᎠᏓᏅᏙ ᎬᏗ.

ale sagwu gesv junilvwisdanedi anahldinvdlv adanvdo gvhdi.

and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Notes

- ^ Ethnologue classifies Cherokee as moribund (8a), which means that "The only remaining active users of the language are members of the grandparent generation and older".[10]

- ^ There was a difference between the old-form DO (Λ-like) and a new-form DO (V-like). The standard Digohweli font displays the new-form. Old Do Digohweli and Code2000 fonts both display the old-form.[89]

- ^ This has been confirmed using an online transliteration service.[which?]

- ^ The PDF Unicode chart shows the new-form of the letter do.

References

- ^ Neely, Sharlotte (March 15, 2011). Snowbird Cherokees: People of Persistence. University of Georgia Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-8203-4074-6. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Frey, Ben (2005). "A Look at the Cherokee Language" (PDF). Tar Heel Junior Historian. North Carolina Museum of History. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Cherokee". Endangered Languages Project. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e McKie, Scott (June 27, 2019). "Tri-Council declares State of Emergency for Cherokee language". Cherokee One Feather. Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "The Cherokee Nation & its Language". University of Minnesota: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Keetoowah Cherokee is the Official Language of the UKB" (PDF). Keetoowah Cherokee News: Official Publication of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma. April 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Language & Culture". United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Archived from the original on April 25, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "UKB Constitution and By-Laws in the Keetoowah Cherokee Language" (PDF). United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ "Language Status". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Ridge, Betty (April 11, 2019). "Cherokees strive to save a dying language". Tahlequah Daily Press. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". UNESCO. 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Scancarelli 2005.

- ^ Schlemmer, Liz (October 28, 2018). "North Carolina Cherokee Say The Race To Save Their Language Is A Marathon". North Carolina Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Overall, Michael (February 7, 2018). "As first students graduate, Cherokee immersion program faces critical test: Will the language survive?". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson, Brad (June 2008b). "Citing Verbs in Polysynthetic Languages: The Case of the Cherokee-English Dictionary". Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 27. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. viii.

- ^ "Cherokee Syllabary". Omniglot. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Feeling et al. 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "Native Languages of the Americas: Cherokee (Tsalagi)". Native Languages of the Americas. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ a b "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue. SIL International. 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ LeBeau, Patrick. Term Paper Resource Guide to American Indian History. Greenwoord. Westport, CT: 2009. p. 132.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. Exploring American History: Penn, William – Serra, Junípero Cavendish. Tarrytown, NY: 2008. p. 829.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Cushman, Ellen (2011). ""We're Taking the Genius of Sequoyah into This Century": The Cherokee Syllabary, Peoplehood, and Perseverance". Wíčazo Ša Review. 26 (1). University of Minnesota Press: 72–75. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.26.1.0067. JSTOR 10.5749/wicazosareview.26.1.0067.

- ^ Sturtevant & Fogelson 2004, p. 337.

- ^ a b c d Wilford, John Noble (June 22, 2009). "Carvings From Cherokee Script's Dawn". The New York Times. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ a b c G. C. (August 13, 1820). "Invention of the Cherokee Alphabet". Cherokee Phoenix. Vol. 1, no. 24.

- ^ a b c Boudinot, Elias (April 1, 1832). "Invention of a New Alphabet". American Annals of Education.

- ^ a b c Davis, John B. (June 1930). "The Life and Work of Sequoyah". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 8 (2). Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Langguth, p. 71

- ^ "Sequoyah". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ "Cherokee language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ O'Brien, Matt (February 28, 2022). "Cherokee on a smartphone: Part of a drive to save a language". Hickory Daily Record. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2022 – via Associated Press.

- ^ "Cherokee: A Language of the United States". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. SIL International. 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "Cherokee Language & Culture". Indian Country Diaries. pbs. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ Scancarelli 2005, p. 351.

- ^ a b Thompson, Irene (August 6, 2013). "Cherokee". aboutworldlanguages.com. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Neal, Dale (January 4, 2016). "Cracking the code to speak Cherokee". Asheville Citizen-Times.

- ^ a b c Cushman, Ellen (September 13, 2012). "8 – Peoplehood and Perseverance: The Cherokee Language, 1980–2010". The Cherokee Syllabary: Writing the People's Perseverance. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 189–191. ISBN 978-0-8061-8548-4. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ "Health Centers & Hospitals". Cherokee Nation. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ "Native Now: Language: Cherokee". We Shall Remain – American Experience – PBS. 2008. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Cherokee Language Revitalization". Cherokee Preservation Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Kituwah Preservation & Education Program Powerpoint, by Renissa Walker (2012)'. 2012. Print.

- ^ Chavez, Will (April 5, 2012). "Immersion students win trophies at language fair". Cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ a b "Cherokee Immersion announces second campus". Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton, Tulsa World, November 2, 2021. November 2, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "Cherokee Language Revitalization Project". Western Carolina University. 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Cherokee Nation opens $20 million immersion facility where English becomes a foreign language". Michael Overall, Tulsa World, November 15, 2022. November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- ^ Sellers, Caroline (June 8, 2023). "Cherokee language lessons now available on two apps". Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Kfor.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2024.

- ^ King 1975, pp. 16, 21.

- ^ a b Lounsbury, Floyd G. (1978). Trigger, Bruce G. (ed.). "Iroquoian Languages". Handbook of North American Indians. 15. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution: 334–343. OCLC 12682465.

- ^ a b Uchihara 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, pp. 39, 64.

- ^ Uchihara 2016, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Scancarelli 1987, p. 25.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 65.

- ^ Uchihara 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Scancarelli 1987, p. 26.

- ^ a b Uchihara 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b Uchihara 2016, p. 43.

- ^ Charles 2010, pp. 21, 82.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 36.

- ^ Uchihara 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, pp. 33, 64.

- ^ Scancarelli 2005, pp. 359–362.

- ^ Scancarelli 1987, p. 30.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. ix.

- ^ a b Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 45.

- ^ Uchihara 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 78.

- ^ Uchihara 2013, pp. 127–130.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 51.

- ^ Dunlap, Mary Jane (November 1, 2011). "Language specialists racing with time to revitalize Cherokee language". The University of Kansas. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Uchihara 2016, p. 95.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. xiii.

- ^ a b Robinson 2004, p. 60.

- ^ Montgomery-Anderson 2008a, p. 49.

- ^ King 1975.

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (1984). "The Evolution of Noun Incorporation". Language. 60 (4): 847–894. doi:10.1353/lan.1984.0038. S2CID 143600392.

- ^ Chafe, Wallace. 2000. "Florescence as a force in grammaticalization." Reconstructing Grammar, ed. Spike Gildea, pp. 39–64. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- ^ Scancarelli 1987, pp. 181–198.

- ^ a b c Feeling 1975, p. 353.

- ^ King 1975, p. 111.

- ^ Akkuş 2018.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. 354.

- ^ Feeling 1975, p. xvii.

- ^ Feeling et al. 2003, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Walker & Sarbaugh 1993.

- ^ "LanguageGeek Fonts: Cherokee". LanguageGeek.

- ^ "Phoreus Cherokee". TypeCulture. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ Avila, Eduardo (September 13, 2015). "How the Cherokee language has adapted to texts, iPhones". Public Radio International, Digital Voices Online. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "Sequoyah's Numerals". Inter tribal. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "Numbers in Cherokee". omniglot.com. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "Dikaneisdi (Word List)". cherokee.org. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ Holmes and Smith, p. vi

- ^ a b Holmes and Smith, p. vii

- ^ Holmes and Smith, p. 43

Bibliography

- Akkuş, F. (2018). "Copular constructions and clausal syntax in Cherokee". In Keough, M.; Weber, N.; Anghelescu, A.; Chen, S. (eds.). Proceedings of the Workshop on the Structure and Constituency of Languages of the Americas 21. University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics. Vol. 46.

- Feeling, Durbin (1975). Cherokee-English Dictionary: Tsalagi-Yonega Didehlogwasdohdi. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Nation.

- Feeling, Durbin; Kopris, Craig; Lachler, Jordan; Van Tuyl, Charles (2003). A Handbook of the Cherokee Verb: A Preliminary Study. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Heritage Center. ISBN 978-0-9742818-0-3.

- Holmes, Ruth Bradley; Sharp Smith, Betty (1976). Beginning Cherokee: Talisgo Galiquogi Dideliquasdodi Tsalagi Digohweli. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Montgomery-Anderson, Brad (May 30, 2008a). "A Reference Grammar of Oklahoma Cherokee" (PDF).

- Montgomery-Anderson, Brad (May 2015). Cherokee Reference Grammar. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4342-2. OCLC 880689691.

- Robinson, Prentice (2004). Conjugation Made Easy: Cherokee Verb Study. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Cherokee Language and Culture. ISBN 978-1-882182-34-3.

- Scancarelli, Janine (2005). "Cherokee". In Scancarelli, Janine; Hardy, Heather K. (eds.). Native Languages of the Southeastern United States. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press in cooperation with the American Indian Studies Research Institute, Indiana University, Bloomington. pp. 351–384. OCLC 56834622.

- Uchihara, Hiroto (2013). "Tone and Accent in Oklahoma Cherokee" (Ph.D. dissertation). Buffalo, State University of New York.

- Uchihara, Hiroto (2016). Tone and Accent in Oklahoma Cherokee. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873944-9.

Concerning the syllabary

- Bender, Margaret (2002). Signs of Cherokee Culture: Sequoyah's Syllabary in Eastern Cherokee Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bender, Margaret (2008). "Indexicality, voice, and context in the distribution of Cherokee scripts". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2008 (192): 91–104. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.037. S2CID 145490610.

- Daniels, Peter T. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 587–592.

- Foley, Lawrence (1980). Phonological Variation in Western Cherokee. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Kilpatrick, Jack F.; Kilpatrick, Anna Gritts. New Echota Letters. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press.

- Tuchscherer, Konrad; Hair, Paul Edward Hedley (2002). "Cherokee and West Africa: Examining the Origins of the Vai Script". History in Africa. 29: 427–486. doi:10.2307/3172173. JSTOR 3172173. S2CID 162073602.

- Sturtevant, William C.; Fogelson, Raymond D., eds. (2004). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Vol. 14. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

- Walker, Willard; Sarbaugh, James (1993). "The Early History of the Cherokee Syllabary". Ethnohistory. 40 (1): 70–94. doi:10.2307/482159. JSTOR 482159. S2CID 156008097.

Further reading

- Bruchac, Joseph, ed. (1995). Aniyunwiya/Real Human Beings: An Anthology of Contemporary Cherokee Prose. Greenfield Center, NY: Greenfield Review Press. ISBN 978-0-912678-92-4.

- Charles, Julian (2010). A History of Iroquoian Languages (PhD dissertation). Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. hdl:1993/4175.

- Cook, William Hinton (1979). A Grammar of North Carolina Cherokee (PhD dissertation). Yale University. OCLC 7562394.

- King, Duane H. (1975). A Grammar and Dictionary of the Cherokee Language (PhD dissertation). University of Georgia. OCLC 6203735.

- Munro, Pamela, ed. (1996). Cherokee Papers from UCLA (PDF). UCLA Occasional Papers in Linguistics. Vol. 16. OCLC 36854333. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2009.

- Pulte, William; Feeling, Durbin (2001). "Cherokee". In Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.). Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages: Past and Present. New York: H. W. Wilson. pp. 127–130. ISBN 0-8242-0970-2.

- Scancarelli, Janine (1987). Grammatical Relations and Verb Agreement in Cherokee (PDF) (PhD dissertation). Los Angeles: University of California. OCLC 40812890. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2024.

- Scancarelli, Janine (1996). "53. Cherokee Writing". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

External links

- Cherokee-English Dictionary Online Database

- Cherokee word list lookup

- Cherokee Nation Dikaneisdi (Word List)

- Cherokee numerals

- Cherokee – Sequoyah transliteration system – online conversion tool

- Cherokee Unicode Chart

- Cherokee Nation ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ ᏖᎩᎾᎶᏥ ᎤᎾᏙᏢᏅᎢ (Tsalagi Gawonihisdi teginalotsi unadotlvnvi) / Cherokee Language Technology

- List of both short and long names for every country and dependency in the world

Language archives, texts, audio, video

- Cherokee Phoenix, bilingual newspaper in Cherokee and English

- Cherokee Traditions digital archive, from Western Carolina University

- Cherokee New Testament Online Online translation of the New Testament. Currently the largest Cherokee document on the internet.

- "Native American Audio Collections: Cherokee". American Philosophical Society. Archived from the original on March 2, 2013. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- Cherokee Language Texts, from the Boston Athenæum: Schoolcraft Collection of Books in Native American Languages. Digital Collection.

Language lessons and online instruction

- Free online Cherokee classes from the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma

- Cherokee Language Online (Beginning dialogues, audio, flashcards and grammar from culturev.com)

- Cherokee Language downloadable flashcard decks (Some based on culturev.com)

- Mango Languages Archived 2021-06-02 at the Wayback Machine has free lessons via their website or app

- Online Cherokee language classes, from Western Carolina University

- Cherokee Language Program at Western Carolina University on Facebook, additional materials

- CherokeeLessons.com (Hosts Creative Commons licensed materials including a textbook covering grammar and many hours of challenge/response based audio lesson files).

- Cherokee language YouTube videos for beginners, by tsasuyeda

- Cherokee speakers, Cherokee Nation