Contents

The French language is spoken as a minority language in the United States. Roughly 2.1 million Americans over the age of five reported speaking the language at home in a federal 2010 estimate,[1][2] making French the fourth most-spoken language in the nation behind English, Spanish, and Chinese (when Louisiana French, Haitian Creole and all other French dialects and French-derived creoles are included, and when Cantonese, Mandarin and other varieties of Chinese are similarly combined).[3]

Several varieties of French evolved in what is now the United States:

- Louisiana French, spoken in Louisiana by descendants of colonists in French Louisiana

- New England French, spoken in New England by descendants of 19th and 20th-century Canadian migrants

- Missouri French, spoken in Missouri by descendants of French settlers in the Illinois Country

- Muskrat French, spoken in Michigan by descendants of habitants, voyageurs and coureurs des bois in the Pays d'en Haut

- Métis French, spoken in North Dakota by Métis people

More recently, French has also been carried to various parts of the nation via immigration from Francophone countries and regions. Today, French is the second most spoken language (after English) in the states of Maine and Vermont. In Louisiana, it is tied with Spanish for second most spoken if Louisiana French and all creoles such as Haitian are included. French is the third most spoken language (after English and Spanish) in the states of Connecticut and Rhode Island.[2][4]

As a second language, French is the second most widely taught foreign language (after Spanish) in American schools, colleges and universities.[5] While the overwhelming majority of Americans of French ancestry grew up speaking only English, some enroll their children in French heritage language classes.

Dialects and varieties

There are three major groups of French dialects that emerged in what is now the United States: Louisiana French, Missouri French, and New England French (essentially a variant of Canadian French).[6]

Louisiana French is traditionally divided into three dialects, Colonial French, Louisiana Creole French, and Cajun French.[7][8] Colonial French is traditionally said to have been the form of French spoken in the early days of settlement in the lower Mississippi River valley, and was once the language of the educated land-owning classes. Cajun French, derived from Acadian French, is said to have been introduced with the arrival of Acadian exiles in the 18th century. The Acadians, the francophone inhabitants of Acadia (modern Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and northern Maine), were expelled from their homeland between 1755 and 1763 by the British. Many Acadians settled in lower Louisiana, where they became known as Cajuns (a corruption of "Acadians"). Their dialect was regarded as the typical language of white lower classes, while Louisiana Creole French developed as the language of the black community. Today, most linguists regard Colonial French to have largely merged with Cajun, while Louisiana Creole remains a distinct variety.[8]

Missouri French was spoken by the descendants of 17th-century French settlers in the Illinois Country, especially in the area of Ste. Genevieve, St. Louis, and in Washington County. In the 1930s there were said to be about 600 French-speaking families in the Old Mines region between De Soto and Potosi.[9] By the late 20th century the dialect was nearly extinct, with only a few elderly speakers able to use it.[7] Similarly, Muskrat French is spoken in southeastern Michigan by descendants of habitants, voyageurs and coureurs des bois who settled in the Pays d'en Haut.[10]

New England French, essentially a local variety of Canadian French, is spoken in parts of the New England states. This area has a legacy of significant immigration from Canada, especially during the 19th and the early 20th centuries. Some Americans of French heritage who have lost the language are currently attempting to revive it.[11][12] Acadian French is also spoken by Acadians in Maine in the Saint John Valley.[13][14]

Métis French is spoken by some Métis people in North Dakota.

Ernest F. Haden identifies the French of Frenchville, Pennsylvania as a distinct dialect of North American French.[15] "While the French enclave of Frenchville, Pennsylvania first received attention in the late 1960s, the variety of French spoken has not been the subject of systematic linguistic study. Haden reports that the geographical origin of its settlers is central France, as was also the case of New Orleans, but with settlement being more recent (1830–1840). He also reports that in the 1960s French seemed to be on the verge of extinction in the state community."[16][17][18]

Brayon French is spoken in the Beauce of Quebec; Edmundston, New Brunswick; and Madawaska, Maine mostly in Aroostook County, Maine. Although superficially a phonological descendant of Acadian French, analysis reveals it is morphosyntactically identical to Quebec French.[19] It is believed to have resulted from a localized levelling of contact dialects between Québécois and Acadian settlers.[20] Some of the Brayons view themselves as neither Acadian nor Québécois, affirming that they are a distinctive culture with a history and heritage linked to farming and forestry in the Madawaska area.

Canadian French spoken by French Canadian immigrants is also spoken by Canadian Americans and French Canadian Americans in the United States across Little Canadas and in many cities of New England. French Canadians living in Canada express their cultural identity using a number of terms. The Ethnic Diversity Survey of the 2006 Canadian census[21][22][23] found that French-speaking Canadians identified their ethnicity most often as French, French Canadians, Québécois, and Acadian. The latter three were grouped together by Jantzen (2006) as "French New World" ancestries because they originate in Canada.[24][25] All these ancestries are represented among French Canadian Americans. Franco-Newfoundlanders speaking Newfoundland French, Franco-Ontarians, Franco-Manitobans, Fransaskois, Franco-Albertans, Franco-Columbians, Franco-Ténois, Franco-Yukonnais, Franco-Nunavois are part of the French Canadian American population and speak their own form of French.

Various dialects of French spoken in France are also spoken in the United States by recent immigrants from France, by people of French ancestry and descendants of immigrants from France.[26][27][28]

Native speaker populations

French ancestry

A total of 10,804,304 people claimed French ancestry in the 2010 census[29] although other sources have recorded as many as 13 million people claiming this ancestry. Most French-speaking Americans are of this heritage, but there are also significant populations not of French descent who speak it as well, including those from Belgium, Switzerland, Haiti and numerous Francophone African countries.

Newer Francophone immigrants

In Florida, the city of Miami is home to a large Francophone community, consisting of French expatriates, Haitians (who may also speak Haitian Creole, a separate language which is derived partially from French), and French Canadians; there is also a growing community of Francophone Africans in and around Orlando and Tampa. A small but sustaining French community that originated in San Francisco during the Gold Rush and was supplemented by French wine-making immigrants to the Bay Area is centered culturally around that city's French Quarter.

In Maine, there is a recent increase of French speakers due to immigration from Francophone countries in Africa.[30][31][32]

Francophone tourists and retirees

Many retired individuals from Quebec have moved to Florida, or at least spend the winter there. Also, the many Canadians who travel to the Southeastern states in the winter and spring include a number of Francophones, mostly from Quebec but also from New Brunswick and Ontario. Quebecers and Acadians also tend to visit Louisiana, as Quebec and New Brunswick share a number of cultural ties with Louisiana.

Seasonal migrations

Florida, California, New York, Texas, Louisiana, Arizona, Hawaii, and a few other popular resort regions (most notably Old Orchard Beach, Maine, Kennebunk and Kennebunkport, Maine and Cape May, New Jersey) are visited in large numbers by Québécois, during winter and summer vacations.

Language study

French has traditionally been the foreign language of choice for English-speakers across the globe. However, after 1968,[33] French has ranked as the second-most-studied foreign language in the United States, behind Spanish.[34] Some 1.2 million students from the elementary grades through high school were enrolled in French language courses in 2007–2008, or 14% of all students enrolled in foreign languages.[35]

Many American universities offer French-language courses, and degree programs in the language are common.[36] In the fall of 2016, 175,667 American university students were enrolled in French courses, or 12.4% of all foreign-language students and the second-highest total of any language (behind Spanish, with 712,240 students, or 50.2%).[37]

French teaching is more important in private schools, but it is difficult to obtain accurate data because of the optional status of languages. Indeed, the study of a foreign language is not required in all states for American students. Some states, however, including New York, Virginia and Georgia, require a minimum of two years of study of a foreign language.

Local communities

Francophone communities

| Town | State | Total population | % Francophone | Francophone population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madawaska | ME | 4,534 | 84% | 3,809 |

| Frenchville | ME | 1,225 | 80% | 980 |

| Van Buren | ME | 2,631 | 79% | 2,078 |

| Berlin | NH | 10,051 | 65% | 6,533 |

| Fort Kent | ME | 4,233 | 61% | 2,582 |

| Town | State | Total population | % Francophone | Francophone population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Agatha | ME | 802 | 80% | 642 |

| Grand Isle | ME | 518 | 76% | 394 |

| St. Francis | ME | 577 | 61% | 352 |

| Saint John Plantation | ME | 282 | 60% | 169 |

| Hamlin | ME | 257 | 57% | 146 |

| Eagle Lake | ME | 815 | 50% | 408 |

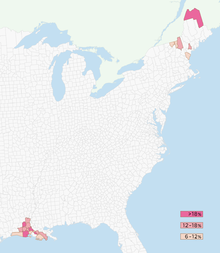

Counties and parishes with the highest proportion of French-speakers

Note: speakers of French-based creole languages are not included in percentages.

| Parish/county | State | Total population | % Francophone | Francophone population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Martin Parish | LA | 48,583 | 27.4% | 13,312 |

| Evangeline Parish | LA | 35,434 | 25.7% | 9,107 |

| Vermilion Parish | LA | 53,807 | 24.9% | 13,398 |

| Aroostook County | ME | 73,938 | 22.4% | 16,562 |

| Lafourche Parish | LA | 89,974 | 19.1% | 17,185 |

| Acadia Parish | LA | 58,861 | 19% | 11,184 |

| Avoyelles Parish | LA | 41,481 | 17.6% | 7,301 |

| Assumption Parish | LA | 23,388 | 17.6% | 4,116 |

| St. Landry Parish | LA | 87,700 | 16.7% | 14,646 |

| Coos County | NH | 33,111 | 16.2% | 5,364 |

| Jefferson Davis Parish | LA | 31,435 | 16.2% | 5,092 |

| Lafayette Parish | LA | 190,503 | 14.4% | 27,432 |

| Androscoggin County | ME | 103,793 | 14.3% | 14,842 |

French place-names

Media and education

Cultural and language governmental bodies

- Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL)

- Massachusetts American and French Canadian Cultural Exchange Commission[38]

Cultural organizations

Television channels

- 3ABN Français, Christian television network 24/7 in French.[39]

- Bonjour Television, the first American television station broadcasting 24/7 totally in French.[40]

- TV5Monde

- Louisiana Public Broadcasting daily afternoon and weekend morning broadcast of French language programs aimed at children on LPB 2

- Canal+ International [41]

Newspapers

Radio stations

- WSRF (AM 1580), Miami area

- WYGG (FM 88.1), central New Jersey

- KFAI (FM 90.3 Minneapolis and 106.7 St.Paul), Minnesota (weekly broadcast is French with English translation, but features French-language music)

- KBON (FM 101.1), southern Louisiana (spoken programming is English, but features French-language music)

- KLCL (AM 1470), southern Louisiana (spoken programming is English, but features French-language music)

- KVPI (1050 AM), southern Louisiana (twice-a-day news broadcast in French, plays English-language music)

- KRVS (FM 88.7), southern Louisiana (variety of programming in English and French)

- WFEA (AM 1370) Manchester, New Hampshire (Sunday morning broadcast in French. Chez Nous with Roger Lacerte)

- WNRI (AM 1380 and FM 95.1) Woonsocket, Rhode Island (Saturday midday, and Sunday afternoon broadcasts of L'Écho Musical with Roger and Claudette Laliberté)

Multimedia Platforms

- Télé-Louisiane: Multimedia platform dedicated to the languages and culture of Louisiana.

- New Niveau

French language schools

- North Seattle French School

- Audubon Charter School, New Orleans[42]

- Dallas International School[43]

- École Bilingue de Berkeley

- École Bilingue de La Nouvelle-Orléans[44]

- Ecole Kenwood French Immersion School, Columbus, Ohio[45]

- San Diego French-American School

- École secondaire Saint-Dominique, Auburn, Maine

- Awty International School, Houston, Texas

- Lycée International de Houston

- Francophone Charter School of Oakland

- French Academy of Bilingual Culture, New Milford, New Jersey

- Lycée Français de New York

- Lycée Français de Los Angeles

- Lycée Français de Chicago

- Lycée Français de la Nouvelle-Orléans

- Lycée Français de San Francisco

- Lycée International de Los Angeles

- French American International School, San Francisco

- French American School of Arizona, Tempe, Arizona

- French-American School of New York

- French American School of Rhode Island, Providence

- International School of Arizona, Scottsdale, Arizona

- International School of Boston

- International School of Denver

- International School of Indiana

- International School of Tucson

- International School of Louisiana (ISL)[46]

- The Language Academy, San Diego

- French International School of Philadelphia[47]

- L'École Française du Maine

- L'Étoile du Nord French Immersion, St. Paul, Minnesota

- French American School of Puget Sound, Mercer Island, Washington

- French Immersion School of Washington

- École Franco-américaine de la Silicon Valley

- French American International School (Portland, Oregon)

- Portland French School, Portland, Oregon

- École Bilingue de Berkeley, Berkeley, California

- John Hanson French Immersion School, Oxon Hill, Maryland

- Robert Goddard French Immersion School, Lanham, Maryland

- The Waring School, French Immersion School, Beverly, Massachusetts

- École Internationale de Boston / International School of Boston, Cambridge and Arlington, Massachusetts

- Normandale French Immersion Elementary School, Edina, Minnesota

- St. Louis Language Immersion Schools, Saint Louis, Missouri

- École Française Bilingue de Greenville, South Carolina

- Lycée Rochambeau, Washington, D.C.

- Académie Lafayette – French Immersion Charter Public School, Kansas City, Missouri

- Santa Rosa French-American Charter School, Santa Rosa, California

See also

- French America

- French Americans

- Quebec

- New Brunswick

- Louisiana

- French Creole

- Quebec French

- Acadian French

- Louisiana French

- Frenchville French

- Louisiana Creole

- Missouri French

- Muskrat French

- New England French

- Canadian French

- Newfoundland French

- French language in Canada

- American French

- Francophonie in Minnesota

- Council for the Development of French in Louisiana

- French colonization of the Americas

References

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau (2003). "Language Use and English-Speaking Ability: 2000" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ a b "LANGUAGE SPOKEN AT HOME BY ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH FOR THE POPULATION 5 YEARS AND OVER : Universe: Population 5 years and over : 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- ^ "LANGUAGE SPOKEN AT HOME BY ABILITY TO SPEAK ENGLISH FOR THE POPULATION 5 YEARS AND OVER : Universe: Population 5 years and over : 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates??". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States".

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich; International Sociological Association (1989). Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 306–308. ISBN 0-89925-356-3. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Ammon, Ulrich; International Sociological Association (1989). Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Walter de Gruyter. p. 307. ISBN 0-89925-356-3. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "What is Cajun French?". Department of French Studies, Louisiana State University. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2010.

- ^ "Creole Dialect of Missouri". J.-M. Carrière, American Speech, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 1939), pp. 109–119

- ^ Au, Dennis. "The Mushrat French: The Survival of French Canadian Folklife on the American Side of le Détroit". Archived from the original on 2014-04-26.

- ^ "Reveil". Wakingupfrench.com. 2006-01-30. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ centralmaine.mainetoday.com https://web.archive.org/web/20090526140218/http://centralmaine.mainetoday.com/news/stories/021118franco_f.shtml. Archived from the original on May 26, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Made in Acadia: The History, Evolution and Unique Expressions of Acadian French". 27 December 2017.

- ^ "Acadians & the St. John Valley | Maine's Aroostook County".

- ^ Haden, Ernest F. 1973. "French dialect geography in North America." In Thomas A. Sebeok (Ed). Current trends in linguistics. The Hague: Mouton, 10.422–439.

- ^ King, Ruth (2000). "The Lexical Basis of Grammatical Borrowing: A Prince Edward Island French Case Study". Amsterdam: John Benjamins: 5.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Phillips, George. "French influence on the English speaking community".

- ^ vorlon.case.edu https://web.archive.org/web/20070206014449/http://vorlon.case.edu/~flm/flm/Frenchville/Frenchville.html. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Geddes, James (1908). Study of the Acadian-French language spoken on the north shore of the Baie-des-Chaleurs. Halle: Niemeyer; Wittmann, Henri (1995) "Grammaire comparée des variétés coloniales du français populaire de Paris du 17e siècle et origines du français québécois." in Fournier, Robert & Henri Wittmann. Le français des Amériques. Trois-Rivières: Presses universitaires de Trois-Rivières, 281–334.

- ^ "Neither American or Canadian: The Republic of Madawaska « All in".

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population". The Daily. Statistics Canada. 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ "Ethnic Diversity Survey: portrait of a multicultural society" (PDF). Statistics Canada. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ Statistics Canada (April 2002). "Ethnic Diversity Survey: Questionnaire" (PDF). Department of Canadian Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

The survey, based on interviews, asked the following questions: "1) I would now like to ask you about your ethnic ancestry, heritage or background. What were the ethnic or cultural origins of your ancestors? 2) In addition to "Canadian", what were the other ethnic or cultural origins of your ancestors on first coming to North America?

- ^ Jantzen, Lorna (2003). "THE ADVANTAGES OF ANALYZING ETHNIC ATTITUDES ACROSS GENERATIONS—RESULTS FROM THE ETHNIC DIVERSITY SURVEY" (PDF). Canadian and French Perspectives on Diversity: 103–118. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Jantzen (2006) Footnote 9: "These will be called "French New World" ancestries since the majority of respondents in these ethnic categories are Francophones."

- ^ "French Immigration to America Timeline **".

- ^ Camarota, Steven A. (8 August 2012). "Immigrants in the United States, 2010".

- ^ "European Immigrants in the United States". 26 July 2012.

- ^ "SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES : 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Reason for Recent French Speaking Resurgence in Lewiston: African Immigrants". 27 March 2017.

- ^ "In Maine, a little French goes a long way". The World from PRX.

- ^ "African immigrants drive French-speaking renaissance in Maine". Portland Press Herald.

- ^ Judith W. Rosenthal, Handbook of Undergraduate Second Language Education (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000; New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 50.

- ^ Ruiz, Rebecca. "By The Numbers: Most Popular Foreign Languages". Forbes.

- ^ "Language study in the US" (PDF). actfl.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- ^ Goldberg, David; Looney, Dennis; Lusin, Natalia (February 2015). "Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in United States Institutions of Higher Education, Fall 2013" (PDF). Modern Language Association. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "MLA Enrollment Survey Press Release 2016" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ "Citizens' Guide to State Services, Housing/Community Development- Commissions". Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Commonowealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on March 16, 2018.

- ^ "Home". 3abnfrancais.org.

- ^ "Home". bonjouramericatv.com.

- ^ "Découvrir nos métiers et marques - Vivendi".

- ^ "Audubon Charter School". Auduboncharter.com. 1999-12-31. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Home". Dallasinternationalschool.org. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Ecole Bilingue de la Nouvelle Orleans - Welcome to EB New Orleans". www.ebnola.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008.

- ^ "Academic Brief / Program Overview".

- ^ http://www.isl-edu.org Archived June 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "About Us | EFIP". Efiponline.com. 1991-01-22. Archived from the original on 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

External links

- History of French settlement in Detroit, MI

- "Feel Like a Canadian in New York". New York in French. 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2020-06-29.