Contents

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts on another country (see also marches). Unlike a border—a rigid and clear-cut form of state boundary[1]—in the most general sense a frontier can be fuzzy or diffuse. For example, the frontier between the Eastern United States and the Old West in the 1800s was an area where European American settlements gradually thinned out and gave way to Native American settlements or uninhabited land. The frontier was not always a single continuous area, as California and various large cities were populated before the land that connected those to the East.

Frontiers and borders also imply different geopolitical strategies. In Ancient Rome, the Roman Republic experienced a period of active expansion and creating new frontiers. From the reign of Augustus onward, the Roman borders turned into defensive boundaries that divided the Roman and non-Roman realms.[2] In the eleventh-century China, China's Song Dynasty defended its northern border with the nomadic Liao empire by building an extensive manmade forest. Later in the early twelfth century, Song Dynasty invaded the Liao and dismantled the northern forest, converting the former defensive border into an expanding frontier.[3]

In modern history, colonialism and imperialism has applied and produced elaborate use and concepts of a frontier, especially in the settler colonial states of North America, expressed by the "Manifest Destiny" and "Frontier Thesis".

Mobile frontiers was discussed during the Schengen convention.[4] It was used by Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru to describe Mao Zedong's actions of grabbing Indian territory before and during the 1962 War through a creeping process.[5] Albert Nevett, in his 1954 book "India Going Red?" wrote that "The Empire of Soviet Communism has 'mobile frontiers'".[6]

Spain

The Spanish "frontier" lies between Spain and Gibraltar and has been in existence since Gibraltar became independent of Spain in 1704. Passports are checked twice - once by Gibraltar and once by Spain - within a short distance of each other. This regularly leads to delays exiting and entering Gibraltar.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, the boundary, border country, the borders of civilisation, or as the land that forms the furthest extent of what was frequently termed "the inside" or "settled" districts.[7] The "outside" was another term frequently used in colonial Australia, this term seemingly[original research?] covered not only the frontier but the districts beyond. Settlers at the frontier thus frequently referred to themselves as "the outsiders" or "outside residents" and to the area in which they lived as "the outside districts". At times one might hear the "frontier" described as "the outside borders".[8] However the term "frontier districts" was seemingly[original research?] used predominantly in the early Australian colonial newspapers whenever dealing with skirmishes between black and white in northern New South Wales and Queensland, and in newspaper reports from South Africa, whereas it was seemingly not so commonly used when dealing with affairs in Victoria, South Australia and southern New South Wales. The use of the word "frontier" was thus frequently connected to descriptions of frontier violence, as in a letter printed in the Sydney Morning Herald in December 1850 which described murder and carnage at the northern frontier and calling for the protection of the settlers saying: "...nothing but a strong body of Native Police will restore and keep order in the frontier districts, and as the squatters are taxed for the purpose of such protection".[9]

South America

Argentina

The southern indigenous frontier of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata was the southern limit into which the viceyolty could exert its rule. Beyond this lay territories[10] de facto controlled by indigenous peoples who inhabited the Pampas and Patagonia. These group were mainly the Tehuelche, Pehuenche, Mapuche,[11] and the Ranqueles.

Various military campaigns and peace treaties were arranged by the Spanish in order to either stop indigenous incursions in Spanish lands or to advance the frontier into indigenous territory.[12]

Under General Julio Argentino Roca, the Conquest of the Desert extended Argentine power into Patagonia.

Chile

The Destruction of the Seven Cities (1599–1604) led to the formation of a frontier called La Frontera, with the Spanish ruling north of Biobío River and Mapuche retaining independence south of the said river. Within this frontier the city of Concepción assumed the role of "military capital" of Spanish-ruled Chile.[13] This informal role was given by the establishment of the Spanish Army of Arauco in the city which was financed by a payments of silver from Potosí called Real Situado.[13] Santiago located at some distance from the war zone remained the political capital since 1578.[13]

Following the Mapuche uprising of 1655 and abolition of Mapuche slavery in 1683 in the Spanish Empire trade across the frontier increased.[14] Mapuche-Spanish and later Mapuche-Chilean trade increased further in the second half of the 18th century as hostilities decreased.[15] Mapuches obtained goods from Chile and some dressed in "Spanish" clothing.[16] Despite close contacts Chileans and Mapuches remained socially, politically and economically distinct.[16] Spanish and later Chilean officials with the titles of comisario de naciones and capitán de amigos acted as intermediaries between the Mapuche and colonial and republican authorities.[17]

During the Occupation of Araucanía the Republic of Chile advanced the frontier south from Bío Bío River to Malleco River where a well defended line of forts was established between 1861 and 1871.

Having decisively defeated Peru in the battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores in January 1881 Chilean authorities turned their attention to the southern frontier in Araucanía seeking to defend the previous advances that had been so difficult to establish.[18][19][20] The idea was not only to defend forts and settlements but also to advance the frontier all the way from Malleco River to Cautín River.[18][20]

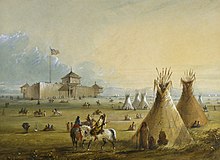

North America

Colonial North America

The word "frontier" has often meant a region at the edge of a settled area, especially in North American development. It was a transition zone where explorers, pioneers and settlers were arriving. Frederick Jackson Turner said that "the significance of the frontier" was that as pioneers moved into the "frontier zone," they were changed by the encounter. For example, Turner argues in 1893 that in the United States, unlimited free land in this zone was available, and thus offered the psychological sense of unlimited opportunity. This, in turn, had many consequences such as optimism, future orientation, shedding the restraints of land scarcity, and the wastage of natural resources.[21]

In the earliest days of European settlement of the Atlantic coast, the frontier was any part of the forested interior of the continent lying beyond the fringe of existing settlements along the coast and the great rivers, such as the St. Lawrence, Connecticut, Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna River and James.[citation needed]

English, French, Spanish and Dutch patterns of settlement were quite different. Only a few thousand French citizens migrated to Canada. These Canadiens settled in villages along the St. Lawrence River, establishing communities that remained stable for long stretches, rather than leapfrogging west the way the English and later the Americans did. Although French fur traders ranged widely through the Great Lakes and Mississippi River watersheds, including as far as the Rocky Mountains, they did not usually settle down. French settlement in these areas was limited to a few very small villages on the lower Mississippi and in the Illinois Country.[22] The Dutch set up fur trading posts in the Hudson River valley, followed by large grants of land to patroons, who brought in tenant farmers that created compact, permanent villages. Dutch efforts at westward expansion were halted by their defeats at the hands of English forces.[23]

The English colonies generally pursued a more unified policy of settlement of the New World, including focusing their efforts on cultivating land in the New World. The typical English settlements were quite compact and small— mostly being under 3 square kilometres (1 square mile). Early frontier areas east of the Appalachian Mountains included the Connecticut River valley.[24] The French and Indian War of the 1760s resulted in a victory for the British, who gained large areas of French colonial territory west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi River in the Treaty of Paris. American settlers began moving across the Appalachians into areas such the Ohio Country and the New River Valley both before and after the American Revolution.[24]

Most of the frontier movement was east to west, but there were other directions as well. The frontier in New England lay to the north; in Nevada to the east; in Florida to the south. Throughout American history, the expansion of settlement was largely from the east to the west, and thus the frontier is often identified with "the west." On the Pacific Coast, settlement moved eastward.[24]

Canadian frontier

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Canada |

|---|

|

| Timeline (list) |

| Historically significant |

| Topics |

| By provinces and territories |

| Cities |

| Research |

A Canadian frontier thesis was developed by Canadian historians Harold Adams Innis and J. M. S. Careless. They emphasized the relationship between the center and periphery. Katerberg argues that "in Canada the imagined West must be understood in relation to the mythic power of the North." [Katerberg 2003] This is reflected in Canadian literature with the phrase "garrison mentality". In Innis's 1930 work The Fur Trade in Canada, he expounded on what became known as the Laurentian thesis: that the most creative and major developments in Canadian history occurred in the metropolitan centers of central Canada and that the civilization of North America is the civilization of Europe. Innis considered place as critical in the development of the Canadian West and wrote of the importance of metropolitan areas, settlements, and indigenous people in the creation of markets. Turner and Innis continue to exert influence over the historiography of the American and Canadian Wests. The Quebec frontier showed little of the individualism or democracy that Turner ascribed to the American zone to the south. The Nova Scotia and Ontario frontiers were rather more democratic than the rest of Canada, but whether that was caused by the need to be self-reliant at the frontier itself, or the presence of large numbers of American immigrants is debated.[citation needed]

The Canadian political thinker Charles Blattberg has argued that such events ought to be seen as part of a process in which Canadians advanced a "border" as distinct from a "frontier" — from east to west. According to Blattberg, a border assumes a significantly sharper contrast between the civilized and the uncivilized since, unlike a frontier process, the civilizing force is not supposed to be shaped by that which it is civilizing. Blattberg criticizes both the frontier and border "civilizing" processes.[citation needed]

Canadian prairies

The pattern of settlement of the Canadian prairies began in 1896, when the American prairie states had already achieved statehood. Like their American counterparts, the Prairie provinces supported populist and democratic movements in the early 20th century.[25]

United States

Following the victory of the United States in the American Revolutionary War and the signing Treaty of Paris in 1783, the United States gained formal, if not actual, control of the British territory west of the Appalachians. Thousands of settlers, typified by Daniel Boone, had already reached Kentucky, Tennessee, and adjacent areas. Some areas, such as the Virginia Military District and the Connecticut Western Reserve (both in Ohio), were used by the states as rewards to veterans of the war. How to formally include these new frontier areas into the nation was an important issue in the Continental Congress of the 1780s and was partly resolved by the Northwest Ordinance (1787). The Southwest Territory saw a similar pattern of settlement pressure.[citation needed][26]

For the next century, the expansion of the nation into these areas, as well as the subsequently acquired Louisiana Purchase, Oregon Country, and Mexican Cession, attracted hundreds of thousands of settlers. Whether the Kansas frontier would become "slave" or "free" kindled the American Civil War. In general before 1860, Northern Democrats promoted easy land ownership and Whigs and Southern Democrats resisted. The Southerners resisted Homestead Acts because it supported the growth of a free farmer population that might oppose slavery.[citation needed]

When the Republican Party came to power in 1860 it promoted a free land policy — notably the Homestead Act of 1862, coupled with railroad land grants that opened cheap (but not free) lands for settlers. In 1890, the frontier line had broken up (Census maps defined the frontier line as a line beyond which the population density was under 2 inhabitants per square mile or 0.8 inhabitants per square kilometre).

The effect of the frontier upon popular culture was enormous, in dime novels, Wild West shows, and, after 1910, Western movies set on the frontier.

The American frontier was generally the westernmost edge of a settlement and typically more free-spirited than in the East because of its lack of social and political institutions. The idea that the frontier provided the core defining quality of the United States was elaborated by the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, who built his Frontier Thesis in 1893 around this notion. Subsequently, the frontier has also been described as the point of contact between two cultures, where contact led to exchanges that affected both cultures.[27]

In popular culture, Alaska: The Last Frontier is an American reality cable television series about Alaskan pioneers, Yule and Ruth Kilcher, at their homestead 11 miles outside of Homer.

Russia

The expansion of Russia to the north, south (Wild Fields) and east (Siberia, the Russian Far East and Russian Alaska) exploited ever-changing frontier regions over several centuries and often involved the development and settlement of Cossack communities.[28]

See also

- Cabin rights

- Frontier thesis

- March (territorial entity)

- Wild Fields

- Military Frontier

- Xinjiang under Qing rule

- Conquest of the Desert

- North-West Frontier Province

Notes

- ^ Mura, Andrea (2016). "National Finitude and the Paranoid Style of the One". Contemporary Political Theory. 15: 58–79. doi:10.1057/cpt.2015.23. S2CID 53724373.

- ^ Luttwak, Edward (1976). The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the First Century CE to the Third. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (July 2018). "FRONTIER, FORTIFICATION, AND FORESTATION: DEFENSIVE WOODLAND ON THE SONG–LIAO BORDER IN THE LONG ELEVENTH CENTURY". Journal of Chinese History. 2 (2): 313–334. doi:10.1017/jch.2018.7. ISSN 2059-1632.

- ^ Zaiotti, Ruben (2011). Cultures of Border Control: Schengen and the Evolution of European Frontiers. University of Chicago Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-226-97787-4.

- ^ Singh, Air Commodore Jasjit (2013-03-15). China's India War, 1962: Looking Back to See the Future: Looking Back to See the Future. KW Publishers Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-85714-79-5.

- ^ Nevett, Albert (1954). India Going Red. Indian Institute of Social Order (Indian Social Institute).

- ^ See e.g. Parliamentary Debate April 14 Legislative Assembly of NSW (Australian April 14, 1848, p.4 Robinson)

- ^ see e.g. Sydney Morning Herald June 6, 1851 p.2g; South Australian Register, Moreton Bay Courier Feb 16, 1861, p2 and 2 April 1861, p.3 re 'The Native Police'; see Queensland Parliamentary Debate (Attorney-General Pring) (Brisbane Courier, July 27, 1861, p5); Queensland Parliamentary Debate 20 August 1863; Brisbane Courier, Aug 22, 1863 (Editorial).

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald Dec 24, 1850, p.3s.

- ^ Gascón, Margarita (2001). "Periferia y frontera al sur del en el sur del virreinato del Perú". La transición de periferia a frontera : mendoza en el siglo XVII (in Spanish). Andes. pp. 4–6. ISSN 0327-1676. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Marimán, P.; Caniuqueo, S.; Millalén, J.; Levil, R. (2006). ¡…Escucha, winka…!: Cuatro ensayos de Historia Nacional Mapuche y un epílogo sobre el futuro (in Spanish). Chile: LOM. ISBN 9562828514.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roulet, Florencia (December 2009). "Mujeres, rehenes y secretarios : mediadores indígenas en la frontera sur del Río de la Plata durante el período hispánico". Colonial Latin America Review (in Spanish). 18 (3): 303. doi:10.1080/10609160903336101. ISSN 1466-1802. S2CID 161223604. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c Enciclopedia regional del Bío Bío (in Spanish). Pehuén Editores. 2006. p. 44. ISBN 956-16-0404-3.

- ^ "La Frontera araucana". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Bengoa 2000, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Bengoa 2000, p. 154.

- ^ "Tipos fronterizos". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Bengoa 2000, pp. 275-276.

- ^ Ferrando 1986, p. 547

- ^ a b Bengoa 2000, pp. 277-278.

- ^ "Frederick Jackson Turner: The Significance of the Frontier in American History (1893)". wwnorton.com. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ^ Clarence Walworth Alvord, The Illinois Country 1673-1818 (1918)

- ^ Arthur G. Adams, The Hudson Through the Years (1996); Sung Bok Kim, Landlord and Tenant in Colonial New York: Manorial Society, 1664-1775 (1987)

- ^ a b c Allan Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (2000)

- ^ Laycock, David. Populism and Democratic Thought in the Canadian Prairies, 1910 to 1945. 1990; Seymour Martin Lipset, Agrarian Socialism (1950).

- ^ "Westward Expansion | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ Anzaldua, Gloria (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

- ^

Richards, John F. (15 May 2003). "7: Frontier Settlement in Russia". The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. California world history library. Vol. 1 (reprint ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press (published 2003). p. 263. ISBN 9780520230750. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

Discharged and unemployed or deserting servicemen, younger sons and other dependents of men already in frontier service in older areas, fleeing criminals, sedentarized steppe Tatars, and cossacks took up residence in or near the new centers. Decade after decade, however, peasants fleeing to the frontier made up the largest category of migrants. [...] The more venturesome Russian migrants avoided the frontier towns and peasant villages in favor of life as cossacks (from the Turkic kazak, meaning 'free man').

References

Chilean history

- Bengoa, José (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche: Siglos XIX y XX (Seventh ed.). LOM Ediciones. ISBN 956-282-232-X.

- Ferrando Kaun, Ricardo (1986). Y así nació La Frontera... (Second ed.). Editorial Antártica. ISBN 978-956-7019-83-0.

US history

- The Frontier In American History by Frederick Jackson Turner

- Billington, Ray Allen.—

- America's Frontier Heritage (1984), an analysis of the frontier experience from perspective of social sciences and historiography

- Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier (1952 and later editions), the most detailed textbook, with highly detailed annotated bibliographies

- Land of Savagery / Land of Promise: The European Image of the American Frontier in the Nineteenth Century (1981)

- Blattberg, Charles Shall We Dance? A Patriotic Politics for Canada (2003), Ch. 3, a comparison of the Canadian 'border' with the American 'frontier'

- Hine, Robert V. and John Mack Faragher. The American West: A New Interpretive History (2000), recent textbook

- Lamar, Howard R. ed. The New Encyclopedia of the American West (1998), 1000+ pages of articles by scholars

- Milner, Clyde A., II ed. Major Problems in the History of the American West 2nd Ed. (1997), primary sources and essays by scholars

- Nichols, Roger L. ed. American Frontier and Western Issues: An Historiographical Review (1986) essays by 14 scholars

- Paxson, Frederic, History of the American Frontier, 1763-1893 (1924)

- Slotkin, Richard, Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (2000), University of Oklahoma Press

Canada

- Blattberg, Charles Shall We Dance? A Patriotic Politics for Canada (2003), Ch. 3, a comparison of the Canadian 'border' with the American 'frontier'

- Cavell, Janice. "The Second Frontier: the North in English-Canadian Historical Writing." Canadian Historical Review 2002 83(3): 364–389. ISSN 0008-3755 Fulltext in Ebsco

- Clarke, John. Land, Power, and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada. McGill-Queen's U. Press, 2001. 747 pp.

- Colpitts, George. Game in the Garden: A Human History of Wildlife in Western Canada to 1940 U. of British Columbia Press, 2002. 216 pp.

- Forkey, Neil S. Shaping the Upper Canadian Frontier: Environment, Society and Culture in the Trent Valley. U. of Calgary Press 2003. 164 pp.

- Katerberg, William H. "A Northern Vision: Frontiers and the West in the Canadian and American Imagination." American Review of Canadian Studies 2003 33(4): 543–563. ISSN 0272-2011 Fulltext online at Ebsco

- Mulvihill, Peter R.; Baker, Douglas C.; and Morrison, William R. "A Conceptual Framework for Environmental History in Canada's North." Environmental History 2001 6(4): 611–626. ISSN 1084-5453. This proposes a five-part conceptual framework for the study of environmental history in the Canadian North. The first element of the framework analyzes approaches to environmental history that are applicable to the Canadian North. The second element reviews historical forces, myths, and defining characteristics that pertain to the region. A third element of the framework tests the validity of Turner's Frontier Thesis and Creighton's Metropolitan Thesis when applied to northern Canada. The fourth element consists of an overview of major northern environmental trends. The final element consists of four interrelated themes that identify the environmental relationships between northern and southern Canada.

Siberian frontier

- Pesterev, V. (2015). Siberian frontier: the territory of fear. Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), London.

Comparative Frontiers

- Ігор Чорновол. Компаративні фронтири: світовий і вітчизняний вимір [in Ukrainian, The Frontier Thesis: a Comparative Approach and Ukrainian Context]. — Київ: "Критика", 2015. — 376 с. https://krytyka.com/ua/products/books/komparatyvni-frontyry-svitovyy-i-vitchyznyanyy-vymir

Further reading

- The World in 2015: National borders undermined? 11-min video interview with Bernard Guetta, a columnist for Libération newspaper and France Inter radio. "For [Guetta], one of the main lessons from international relations in 2014 is that national borders are becoming increasingly irrelevant. These borders, drawn by the colonial powers, were and still are entirely artificial. Now, people want borders along national, religious or ethnic lines. Bernard Guetta calls this a "comeback of real history"."

- Mura, Andrea (2016). "National Finitude and the Paranoid Style of the One". Contemporary Political Theory. 15: 58–79. doi:10.1057/cpt.2015.23. S2CID 53724373.

- Struck, Bernhard, Border Regions, EGO - European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2013, retrieved: March 8, 2021 (pdf).