Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Causes

-

2Social & political impacts

-

3Housewives' and Mothers' Activism in the Great Depression

-

4Homelessness during the Great Depression

-

5Contraception during the Great Depression

-

6Global comparison of severity

-

7Tight monetary policy

-

8Political responses of the depression era

-

9Recession of 1937–1938

-

10Afterward

-

11Facts and figures

-

12See also

-

13References

-

14Further reading

-

15External links

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

In the United States, the Great Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and then spread worldwide. The nadir came in 1931–1933, and recovery came in 1940. The stock market crash marked the beginning of a decade of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, deflation, plunging farm incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth as well as for personal advancement. Altogether, there was a general loss of confidence in the economic future.[1]

The usual explanations include numerous factors, especially high consumer debt, ill-regulated markets that permitted overoptimistic loans by banks and investors, and the lack of high-growth new industries. These all interacted to create a downward economic spiral of reduced spending, falling confidence and lowered production.[2] Industries that suffered the most included construction, shipping, mining, logging, and agriculture. Also hard hit was the manufacturing of durable goods like automobiles and appliances, whose purchase consumers could postpone. The economy hit bottom in the winter of 1932–1933; then came four years of growth until the recession of 1937–1938 brought back high levels of unemployment.[3]

The Depression caused major political changes in America. Three years into the depression, President Herbert Hoover, widely blamed for not doing enough to combat the crisis, lost the election of 1932 to Franklin Delano Roosevelt by a landslide. Roosevelt's economic recovery plan, the New Deal, instituted unprecedented programs for relief, recovery and reform, and brought about a major realignment of politics with liberalism dominant and conservatism in retreat until 1938.

There were mass migrations of people from badly hit areas in the Great Plains (the Okies) and the South to places such as California and the cities of the North (the Great Migration).[4][5] Racial tensions also increased during this time.

The memory of the Depression also shaped modern theories of government and economics and resulted in many changes in how the government dealt with economic downturns, such as the use of stimulus packages, Keynesian economics, and Social Security. It also shaped modern American literature, resulting in famous novels such as John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men.

Causes

Monetary interpretations

Examining the causes of the Great Depression raises multiple issues: what factors set off the first downturn in 1929; what structural weaknesses and specific events turned it into a major depression; how the downturn spread from country to country; and why the economic recovery was so prolonged.[6]

Many rural banks began to fail in October 1930 when farmers defaulted on loans. There was no federal deposit insurance during that time as bank failures were considered a normal part of economic life. Worried depositors started to withdraw savings, so the money multiplier worked in reverse. Banks were forced to liquidate assets (such as calling in loans rather than creating new loans).[7] This caused the money supply to shrink and the economy to contract (the Great Contraction), resulting in a significant decline in aggregate investment. The decreased money supply further aggravated price deflation, putting more pressure on already struggling businesses.

The U.S. Government's commitment to the gold standard prevented it from engaging in expansionary monetary policy.[clarification needed] High interest rates needed to be maintained in order to attract international investors who bought foreign assets with gold. However, the high interest also inhibited domestic business borrowing.[citation needed] The U.S. interest rates were also affected by France's decision to raise their interest rates to attract gold to their vaults. In theory, the U.S. would have two potential responses to that: allow the exchange rate to adjust, or increase their own interest rates to maintain the gold standard. At the time, the U.S. was pegged to the gold standard. Therefore, Americans converted their dollars into francs to buy more French assets, the demand for the U.S. dollar fell, and the exchange rate increased. One of the only things the U.S. could do to get back into equilibrium was increase interest rates.[citation needed]

In the late 20th century, Winner of the Swedish Central Bank Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences economist Milton Friedman and his fellow monetarist Anna Schwartz argued that the Federal Reserve could have stemmed the severity of the Depression, but failed to exercise its role of managing the monetary system and ameliorating banking panics, resulting in a Great Contraction of the economy from 1929 until the New Deal began in 1933.[8] This view was endorsed by Fed Governor Ben Bernanke who in 2002 said in a speech honoring Friedman and Schwartz:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression, you're right. We did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.[9][8]

— Ben S. Bernanke

Stock market crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 is often cited as the beginning of the Great Depression. It began on October 24, 1929, and kept going down until March 1933. It was the longest and most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States. Much of the stock market crash can be attributed to exuberance and false expectations. In the years leading up to 1929, the rising stock market prices had created vast sums of wealth in relation to amounts invested, in turn encouraging borrowing to buy more stock. However, on October 24 (Black Thursday), share prices began to fall and panic selling caused prices to fall sharply. On October 29 (Black Tuesday), share prices fell by $14 billion in a single day, more than $30 billion in the week.[10] The value that evaporated that week was ten times more than the entire federal budget and more than all of what the U.S. had spent on World War I. By 1930 the value of shares had fallen by 90%.[11]

Since many banks had also invested their clients' savings in the stock market, these banks were forced to close when the stock market crashed. After the stock market crash and the bank closures, people were afraid of losing more money. Because of their fears of further economic challenge, individuals from all classes stopped purchasing and consuming. Thousands of individual investors who believed they could get rich by investing on margin lost everything they had. The stock market crash severely impacted the American economy.

Banking failures

A large contribution was the closure and suspension of thousands of banks across the country. Financial institutions failed for several reasons, including unregulated lending procedures, confidence in the gold standard, consumer confidence in future economics, and agricultural defaults on outstanding loans. With these compounding issues the banking system struggled to keep up with the public's increasing demand for cash withdrawals. This overall decreased the money supply and forced the banks to resort to short or liquidate existing loans.[7] In the race to liquidate assets the banking system began to fail on a wide scale. In November 1930 the first major banking crisis began with over 800 banks closing their doors by January 1931. By October 1931 over 2100 banks were suspended with the highest suspension rate recorded in the St. Louis Federal Reserve District, with 2 out of every 5 banks suspended.[12] The economy as a whole experienced a massive reduction in banking footholds across the country amounting to more than nine thousand closed banks by 1933.

The closures resulted in a massive withdrawal of deposits by millions of Americans estimated at near $6.8 billion ($136 billion in 2023 dollars). During this time the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was not in place resulting in a loss of roughly $1.36 billion (or 20%) of the total $6.8 billion accounted for within the failed banks. These losses came directly from everyday individuals' savings, investments and bank accounts. As a result, GDP fell from the high seven-hundreds in 1929 to the low to mid six-hundreds in 1933 before seeing any recovery for the first time in nearly 4 years.[13] Federal leadership intervention is highly debated on its effectiveness and overall participation. The Federal Reserve Act could not effectively tackle the banking crisis as state bank and trust companies were not compelled to be a member, paper eligible discount member banks heavily restricted access to the Federal Reserve, power between the twelve Federal Reserve banks was decentralized and federal level leadership was ineffective, inexperienced, and weak.

Unregulated banking growth

Throughout the early 1900s banking regulations were extremely lax if not non-existent. The Currency Act of 1900 lowered the required capital of investors from 50,000 to 25,000 to create a national bank. As a result of this change nearly two thirds of the banks formed over the next ten years were quite small, averaging just above the 25,000 in required capital.[14] The number of banks would nearly double (number of banks divided by Real GDP) from 1890 to 1920 due to the lack of oversight and qualification when banking charters were being issued in the first two decades of the 1900s.[15]

The unregulated growth of small rural banking institutions can be partially attributed to the rising cost of agriculture especially in the Corn Belt and Cotton Belt. Throughout the corn and cotton belts real estate increases drove the demand for more local funding to continue to supply rising agricultural economics. The rural banking structures would supply the needed capital to meet the farm commodity market, however, this came with a price of reliability and low risk lending. Economic growth was promising from 1887 to 1920 with an average of 6 percent growth in GDP. In particular, the participation in World War I drove a booming agricultural market that drove optimism at the consumer and lending level which, in turn, resulted in a more lax approach in the lending process. Over banked conditions existed which pressured struggling banks to increase their services (specifically to the agricultural customers) without any additional regulatory oversight or qualifications. This dilemma introduced several high-risk and marginal business returns to the banking market.[16] Banking growth would continue through the first two decades well outside of previous trends disregarding the current economic and population standards. Banking profitability and loan standards begin to deteriorate as early as 1900 as a result.

Crop failures beginning in 1921 began to impact this poorly regulated system, the expansion areas of corn and cotton suffered the largest due to the Dust Bowl era resulting in real estate value reductions. In addition, the year 1921 was the peak for banking expansion with roughly 31,000 banks in activity, however, with the failures at the agricultural level 505 banks would close between 1921 and 1930 marking the largest banking system failure on record. Regulatory questions began to hit the debating table around banking qualifications as a result; discussions would continue into the Great Depression as not only were banks failing but some would disappear altogether with no rhyme or reason.[17] The panic of financial crisis would increase in the Great Depression due to the lack of confidence in the regulatory and recovery displayed during the 1920s, this ultimately drove a nation of doubts, uneasiness, and lack of consumer confidence in the banking system.

Contagion

With a lack of consumer confidence in the economic direction given by the federal government panic started to spread across the country shortly after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. President Hoover retained the Gold Standard as the country's currency gauge throughout the following years. As a result, the American shareholders with the majority of the gold reserves began to grow wary of the value of gold in the near future. Europe's decision to move away from the Gold Standard caused individuals to start to withdraw gold shares and move the investments out of the country or began to hoard gold for future investment. The market continued to suffer due to these reactions, and as a result caused several of the everyday individuals to speculate on the economy in the coming months. Rumors of market stability and banking conditions began to spread, consumer confidence continued to drop and panic began to set in. Contagion spread like wildfire pushing Americans all over the country to withdraw their deposits en masse. This idea would continue from 1929 to 1933 causing the greatest financial crisis ever seen at the banking level pushing the economic recovery efforts further from resolution. An increase in the currency-deposit ratio and a money stock determinant forced money stock to fall and income to decline. This panic-induced banking failure took a mild recession to a major recession.[18]

Whether this caused the Great Depression is still heavily debated due to many other attributing factors. However, it is evident that the banking system suffered massive reductions across the country due to the lack of consumer confidence. As withdraw requests would exceed cash availability banks began conducting steed discount sales such as fire sales and short sales. Due to the inability to immediately determine current value worth these fire sales and short sales would result in massive losses when recuperating any possible revenue for outstanding and defaulted loans. This would allow healthy banks to take advantage of the struggling units forcing additional losses resulting in banks not being able to deliver on depositor demands and creating a failing cycle that would become widespread.[19] Investment would continue to stay low through the next half-decade as the private sector would hoard savings due to uncertainty of the future. The federal government would run additional policy changes such as the Check tax, monetary restrictions (including reduction of money supply by burning), High Wage Policy, and the New Deal through the Hoover and Roosevelt administration.

Social & political impacts

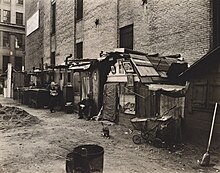

One visible effect of the depression was the advent of Hoovervilles, which were ramshackle assemblages on vacant lots of cardboard boxes, tents, and small rickety wooden sheds built by homeless people. Residents lived in the shacks and begged for food or went to soup kitchens. The term was coined by Charles Michelson, publicity chief of the Democratic National Committee, to refer sardonically to President Herbert Hoover whose policies Michelson blamed for the depression.[20]

The government did not calculate unemployment rates in the 1930s. The most widely accepted estimates of unemployment rates for the Great Depression are those by Stanley Lebergott from the 1950s. He estimated that unemployment reached 24.9 percent in the worst days of 1933. Another commonly cited estimate is by Michael Darby in 1976. He put the unemployment rate at a peak of 22.5 percent in 1932.[21] Job losses were less severe among women, workers in non durable industries (such as food and clothing), services and sales workers, and those employed by the government. Unskilled inner city men had much higher unemployment rates. Age also played a factor. Young people had a hard time getting their first job. Men over the age of 45, if they lost their job, would rarely find another one because employers had their choice of younger men. Millions were hired in the Great Depression, but men with weaker credentials were not, and they fell into a long-term unemployment trap. The migration in the 1920s that brought millions of farmers and townspeople to the bigger cities suddenly reversed itself. Unemployment made the cities unattractive, and the network of kinfolk and more ample food supplies made it wise for many to go back.[22] City governments in 1930–31 tried to meet the depression by expanding public works projects, as President Herbert Hoover strongly encouraged. However, tax revenues were plunging, and the cities as well as private relief agencies were totally overwhelmed by 1931; no one was able to provide significant additional relief. People fell back on the cheapest possible relief, including soup kitchens providing free meals to anyone who showed up.[23] After 1933, new sales taxes and infusions of federal money helped relieve the fiscal distress of the cities, but the budgets did not fully recover until 1941.

The federal programs launched by Hoover and greatly expanded by President Roosevelt's New Deal used massive construction projects to try to jump-start the economy and solve the unemployment crisis. The alphabet agencies CCC, FERA, WPA and PWA built and repaired the public infrastructure in dramatic fashion, but did little to foster the recovery of the private sector. FERA, CCC and especially WPA focused on providing unskilled jobs for long-term unemployed men.

The Democrats won easy landslide victories in 1932 and 1934, and an even bigger one in 1936; the hapless Republican Party seemed doomed. The Democrats capitalized on the magnetic appeal of Roosevelt to urban America. The key groups were low-skilled and Catholics, Jews, and Blacks were especially impacted. The Democrats promised and delivered in terms of political recognition, labor union membership, and relief jobs. The cities' political machines were stronger than ever, for they mobilized their precinct workers to help families who needed help the most navigate the bureaucracy and get on relief. FDR won the vote of practically every demographic in 1936, including taxpayers, small business and the middle class. However, the Protestant middle-class voters turned sharply against him after the recession of 1937–38 undermined repeated promises that recovery was at hand. Historically, local political machines were primarily interested in controlling their wards and citywide elections; the smaller the turnout on election day, the easier it was to control the system. However, for Roosevelt to win the presidency in 1936 and 1940, he needed to carry the electoral college and that meant he needed the largest possible majorities in the cities to overwhelm rural voters. The machines came through for him.[24] The 3.5 million voters on relief payrolls during the 1936 election cast 82% percent of their ballots for Roosevelt. The rapidly growing, energetic labor unions, chiefly based in the cities, turned out 80% for FDR, as did Irish, Italian and Jewish communities. In all, the nation's 106 cities over 100,000 population voted 70% for FDR in 1936, compared to his 59% elsewhere. Roosevelt worked very well with the big city machines, with the one exception of his old nemesis, Tammany Hall in Manhattan. There he supported the complicated coalition built around the nominal Republican Fiorello La Guardia, and based on Jewish and Italian voters mobilized by labor unions.[25]

In the 1938 United States elections the Republicans made an unexpected comeback, and Roosevelt's efforts to purge the Democratic Party of his political opponents backfired badly. The conservative coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats took control of Congress, outvoted the urban liberals, and halted the expansion of New Deal ideas. Roosevelt survived in 1940 thanks to his margin in the Solid South and in the cities. In the North the cities over 100,000 gave Roosevelt 60% of their votes, while the rest of the North favored Willkie 52–48%.[26]

With the start of full-scale war mobilization in the summer of 1940, the economies of the cities rebounded. Even before Pearl Harbor, Washington pumped massive investments into new factories and funded round-the-clock munitions production, guaranteeing a job to anyone who showed up at the factory gate.[27] The war brought a restoration of prosperity and hopeful expectations for the future across the nation. It had the greatest impact on the cities of the West Coast, especially Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Portland and Seattle.[28]

Economic historians led by Price Fishback have examined the impact of New Deal spending on improving health conditions in the 114 largest cities, 1929–1937. They estimated that every additional $153,000 in relief spending (in 1935 dollars, or $1.95 million in year 2000 dollars) was associated with a reduction of one infant death, one suicide, and 2.4 deaths from infectious disease.[29][30]

Housewives' and Mothers' Activism in the Great Depression

The Great Depression's political landscape proved conducive to the first large-scale movement of class-conscious working-class women organizers since the country's founding. Housewives, mothers, and working-class women regardless of employment status were driven by rising market prices to become political players within their communities. Black women and immigrant women were essential to these movements, mobilizing their communities to advocate for better conditions. This activism included food boycotts, anti-eviction rallies, the establishment of barter networks, calls for price regulations for food and housing, and gardening co-ops to battle food insecurity.[31]

Women in the United States have a long history of activism regarding housing and the cost of food despite the common and longstanding misconception that homemakers are passive and apolitical. The rising prices in the U.S. meant a new issue for consumers: the concept of being an "ethical consumer" and reckoning with their own consumer behavior in the ever-changing markets.[32] As the government acted minimally at the time to protect consumers from predatory market tactics, many women as workers, housewives, and mothers found activism a natural part of their role in the name of protecting their families.[32]

Demonstrations and Union Activity

The boycotts done by housewives predominantly revolved around targeting unfair businesses in their communities that price-gauged their shops or refused to support their workers' livelihoods to an acceptable degree. Housewives in New York were particularly active at this time, but housewives and mothers across the country mobilized in this ongoing time of hardship. Historian Annelise Orleck recounts the following demonstrations from a variety of communities:

In New York City, organized bands of Jewish housewives fiercely resisted eviction, arguing that they were merely doing their jobs by defending their homes and those of their neighbors. Barricading themselves in apartments, they made speeches from tenement windows, wielded kettles of boiling water, and threatened to scald anyone who attempted to move furniture out on to the street. Black mothers in Cleveland, unable to convince a local power company to delay shutting off electricity in the homes of families who had not paid their bills, won restoration of power after they hung wet laundry over every utility line in the neighborhood. They also left crying babies on the desks of caseworkers at the Cleveland Emergency Relief Association, refusing to retrieve them until free milk had been provided for each child. These actions reflected a sense of humor but sometimes housewife rage exploded. In Chicago, angry Polish housewives doused thousands of pounds of meat with kerosene and set it on fire at the warehouses of the Armour Company to dramatize their belief that high prices were not the result of shortages.

— Annelise Orleck, "We Are That Mythical Thing Called The Public": Militant Housewives During The Great Depression

Formal organizations were formed by housewives as well, based on the power of these earlier community-based demonstrations: United Council of Working Class Women, Women's Committee of the Washington Commonwealth Federation, Women's Committee against the High Cost of Living, Housewives Industrial League, and the Housewives' League of Detroit to name a few.[31][33]

New ways of activism came out of these boycotts and a renewed awareness of where folks were putting their money came with concerns from American consumers. One unique demonstration by the League of Women Shoppers and Lee Simonson was a fashion show, attended by high society women of D.C., urging consumers to boycott unethically sourced (to protest Japanese actions during the 30's) and overpriced Japanese silk (a popular luxury fabric at the time). Simultaneously, a large number of predominantly unemployed women (as well as some garment workers and representatives from the American Federation of Hosiery Workers) outside the show marched in protest of the boycott, opening a national conversation about the definition of ethical consumerism. This was one of America's first highly effective acts of fashion activism.[34]

As women either returned or began to enter the workforce, the deplorable conditions quickly became clear to them. The lack of sanitation practices, poor wages, and otherwise unsafe work environments were no longer issues that workers were willing to power through when so many other burdens were weighing on them outside of the workplace.[32] The 1930s brought falling wages and high unemployment, which had workplaces implementing strong efforts to keep women and Black folks out of jobs to better employ the preferred white male population, as well as keeping the few female and/or Black workers out of unions. International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Farmer-Labor Women's Federation of Minnesota, and American Federation of Labor were all run by working-class women demanding better conditions to work and raise their families under. The speeches and demonstrations done by these groups of women underscored the dichotomy of the positions they assumed in society under early feminism: The home may be the woman's place, but the "home" was no longer just the family's isolated home and property.[31]

Black Women's Roles

Black women served a particularly radical role through the furthering of working-class women's movements. The Great Depression had particularly strong effects on the Black community in the 1920s and 30s, forcing Black women to reckon with their relationship to the U.S. government. Due to the downturned economy, jobs were scarce and Black men were a huge target of the lay-offs, making up a large population of the unemployed during the Depression. Black folks were also still unable to vote at this time in the Jim Crow south, meaning Black families were facing immense compounding pressures. These conditions set the precedent for Black women to take action and demand the government expand welfare. In collaboration with their white counterparts, Black women would help to form the National Welfare Rights Organization.[33] "Don't Buy Where You Can't Work" boycotts broke out in Black communities, using the role of the homemaking consumer to leverage jobs for Black adults.[35] Black housewives lead marches calling for the government to regulate prices on food while nurses from Black communities set up reproductive health and pre/post natal clinics. Midwife Maude E. Callen is noted by many to have been the biggest player in reforming healthcare for Black folks during the Depression.

The efforts of these "Militant Housewives"[31] had lasting effects on the United States, predominantly the expansion of welfare and the growth of diverse feminist movements, as well as the strengthening of unionization movements in the U.S.

Homelessness during the Great Depression

As the Great Depression trekked onward, homelessness spiked. For the first time in American history, the issue of homelessness was brought to the forefront of the public eye. In search of work, men would board trains and travel across the country, in hopes of finding a way to send money back to their families back home. These men became known as "transients", which was the most common way to refer to these unemployed, homeless individuals. Large urban areas, like San Francisco and New York, became flooded with transients searching for work, causing major train stations to be overcrowded with illegal passengers.[36]

Homeless individuals who were not transient often stayed in municipal shelters, which were government-run homeless shelters that provided housing and food. Because these shelters were often placed in large urban area, they were often overcrowded with poor-quality food and state of living. Soup kitchens also became popular during this time as they were a way for people to access free food. However, these soup kitchens were also overcrowded and often ran out of food before everyone could be served, so they were not always a reliable source of food.

Homeless individuals that did not stay in shelters sometimes stayed in shantytowns, or "Hoovervilles" (named after Herbert Hoover, the president in office when the Depression began). These "Hoovervilles" were self-made communities of homeless people that followed their own rules and established their own society. Men, women, and even some children lived in these shantytowns and people from all different types of socio-economic backgrounds lived together, which was very uncommon during the time of segregation.[37]

Although the African American community was one of the hardest hit during the Great Depression, their struggle during this time often went unnoticed. Homeless African Americans were practically invisible during this time as the effects of Jim Crow and segregation were in full force. Many municipal shelters in the North were segregated and turned away from the aid that was offered there. While other shelters accepted African Americans, the fear of racial violence and discrimination from the municipal organizers or other residents was still a threat that lingered over their heads. Many homeless shelters were also located in inconvenient neighborhoods for African Americans, so they were unable to access them. If municipal shelters for African Americans in the North were limited, they were nonexistent in the South. Many homeless African Americans relied on aid from their own communities. Churches and Black-run organizations often provided their own soup kitchens and shelters to make up for aid the government wasn't providing its African American citizens.[38]

Contraception during the Great Depression

Both birth control and abortion were illegal prior to and during the Great Depression. With the economic downturn, more families turned toward birth control and abortion to help control family sizing, due to not being able to afford children.

In 1936, thousands of women in New Jersey had an abortion "insurance" with more being card-carrying members to a "Birth Control Club", which allowed them access to regular exams and abortions for a fee. This shows that compared to the past, women were now expecting to have abortions, and looking for ways to help lower the cost in the future.[39] Maternal mortality rates rose during the depression, resulting from infections or hemorrhages of self-performed abortions, or methods that women used to try and control their reproduction.[39][40] The New York Academy of Medicine conducted a study and found that 12.8% of maternal deaths were due to septic abortion. With lower-class women attempting to self-abort due to their new poverty, preventing them from visiting a physician or a midwife to perform the abortion.[39]

The Comstock laws effectively prevented women from accessing or talking about contraception until 1950 when it was repealed with the Griswold v. Connecticut case. Only a few states allowed physicians to provide information and contraception.[40] Despite this, women and companies found ways around this law to receive and provide birth control. The most popular method was to conceal the intended function of products by marketing them as "feminine hygiene products", "protections", "security", and "dependability”. In 1930, a legal verdict allowed contraceptive companies to freely advertise their products if the product's sole purpose was not birth control.[40] Companies that previously avoided the birth control market capitalized on this opportunity and the demand for birth control was rapidly growing. Department stores became the most popular place to receive female contraception and these stores created departments where women could shop for contraception in privacy. When women were becoming wary of purchasing inside department stores, manufacturers switched to selling at their homes. In 1930, female contraceptives outnumbered condom sales five to one. By 1940, the market size was three times what it was in 1935.[40]

Global comparison of severity

The Great Depression began in the United States of America and quickly spread worldwide.[41] It had severe effects in countries both rich and poor. Personal income, consumption, industrial output, tax revenue, profits and prices dropped, while international trade plunged by more than 50%. Unemployment in the U.S. rose to 25%, and in some countries rose as high as 33%.[42]

Cities all around the world were hit hard, especially those dependent on heavy industry. Construction was virtually halted in many countries. Farming and rural areas suffered as crop prices fell by approximately 60%.[43][44] Facing plummeting demand with few alternate sources of jobs, areas dependent on primary sector industries such as grain farming, mining and logging, as well as construction, suffered the most.[45]

Most economies started to recover by 1933–34. However, in the U.S. and some others the negative economic impact often lasted until the beginning of World War II, when war industries stimulated recovery.[46]

There is little agreement on what caused the Great Depression, and the topic has become highly politicized. At the time the great majority of economists around the world recommended the "orthodox" solution of cutting government spending and raising taxes. However, British economist John Maynard Keynes advocated large-scale government deficit spending to make up for the failure of private investment. No major nation adopted his policies in the 1930s.[47]

Europe

- Europe as a whole was badly hit, in both rural and industrial areas. Democracy was discredited in most countries.[48]

- As the Great Depression in the United Kingdom worsened, there were no programs in Britain comparable to the New Deal.

- In France, the "Popular Front" government of Socialists with some Communist support, was in power 1936–1938. It briefly tried major programs favoring labor and the working class, but engendered stiff opposition.

- Germany during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) fully recovered and was prosperous in the late 1920s. The Great Depression hit in 1929 and was severe. The political system descended into violence and the Nazi Party led by Adolf Hitler came to power through a series of elections in the early 1930s. Economic recovery was pursued through autarky, pressure on economic partners, wage controls, price controls, and spending programs such as public works and, especially, military spending.

- Spain was a poor rural nation that saw mounting political crises that led in 1936–1939 to the Spanish Civil War. Damage was great. 1939 saw the takeover of the country by Francisco Franco's Nationalist faction.

- In Benito Mussolini's Italy, the economic controls of his corporate state were tightened. The economy was never prosperous.

Canada and the Caribbean

- In Canada, Between 1929 and 1939, the gross national product dropped 40%, compared to 37% in the U.S. Unemployment reached 28% at the depth of the Depression in 1929 and 1930,[49] while wages bottomed out in 1933.[50] Many businesses closed, as corporate profits of Can$396 million in 1929 turned into losses of $98 million in 1933. Exports shrank by 50% from 1929 to 1933. The worst hit were areas dependent on primary industries such as farming, mining and logging, as prices fell and there were few alternative jobs. Some families saw most or all of their assets disappear and their debts became heavier as prices fell. Local and provincial government set up relief programs but there was no nationwide New Deal-like program.

- The effects of the Great Depression in Canada were heavily regionalized. The Prairie Provinces's economies, which had experienced strong economic growth during the 1920s, were poor for most of the 1930s. British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec initially experienced sharp economic contractions, which were followed by reasonably strong recoveries, with some sectors of their economies even experiencing strong growth in the latter half of the 1930s. Meanwhile, in the Maritimes the Great Depression had the effect of exacerbating economic conditions that had been poor since the mid-1920s.[51]

- The Conservative government of Prime Minister R. B. Bennett retaliated against the American high tariff act of 1930. It raised tariffs on U.S. goods and lowered them on British Empire goods. Nevertheless, the Canadian economy suffered. In 1935, Bennett proposed a series of programs that resembled the New Deal; but was defeated in the elections of that year and no such programs were passed.[52]

- Cuba and the Caribbean saw their greatest unemployment during the 1930s because of a decline in exports to the U.S., and a fall in export prices.[citation needed]

Asia

- Japan's economy expanded at the rate of 5% of GDP per year after the years of modernization. Manufacturing and mining came to account for more than 30% of GDP, more than twice the value for the agricultural sector. Most industrial growth, however, was geared toward expanding the nation's military power. Beginning in 1937 much of Japan's energy was focused on a large-scale war and occupation of China.

- China's severe depression was worsened by the Second Sino-Japanese War during most of the 1930s, in addition to internal struggles between Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang and Mao Zedong's Communist Party.

Australia and New Zealand

- In Australia, 1930s conservative and Labor-led governments concentrated on cutting spending and reducing the national debt.[citation needed]

- In New Zealand, a series of economic and social policies similar to the New Deal were adopted after the election of its First Labor Government in the 1935 general election.[53]

Tight monetary policy

The stock market crash in 1929 not only affected the business community and the public's economic confidence, but it also led to the banking system soon after the turmoil. The boom of the US economy in the 1920s was based on high indebtedness, and the rupture of the debt chain caused by the collapse of the bank had produced widespread and far-reaching adverse effects. It is precisely because of the shaky banking system, the United States was using monetary policy to save the economy that had been severely constrained. The American economist Charles P. Kindleberger of long-term studying of the Great Depression pointed out that in the 1929, before and after the collapse of the stock market, the Fed lowered interest rates, tried to expand the money supply and eased the financial market tensions for several times; however, they were not successful. The fundamental reason was that the relationship between various credit institutions and the community was in a drastic adjustment process, the normal supply channels for money supply were blocked.[54] Later, some economists argued that the Fed should do a large-scale opening market business at that time, but the essence of the statement was that the US government should be quick to implement measures to expand fiscal spending and fiscal deficits.

Hoover Administration and the gold standard

Between the 1920s and 1930s, The United States began to try the tight money policy to promote economic growth. In terms of the fiscal policy, the US government failed to reach a consensus on the fiscal issue. President Hoover began to expand federal spending, setting up the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide emergency assistance to banks and financial institutions that were on the verge of bankruptcy. Hoover's fiscal policy had accelerated the recession. In December 1929, as means of showing government confidence in the economy, Hoover reduced all income tax rates by 1% in 1929 due to the continuing budget surplus. By 1930, the surplus had turned into a fast-growing deficit of economic contraction. In 1931, the US federal fiscal revenue and expenditure changed from the financial surplus to a deficit for the first time (the deficit was less than 2.8% of GDP).

By the end of 1931, Hoover had decided to recommend a large increase in taxes to balance the budget; in addition, Congress approved the tax increase in 1932, a substantial reduction in personal immunity to increase the number of taxpayers, and the interest rates had risen sharply, the lowest marginal rate rose from 25% on taxable income in excess of $100,000 to 63% on taxable income in excess of $1 million as the rates were made much more progressive.

Hoover changed his approach to fighting the Depression. He justified his call for more federal assistance by noting that "We used such emergency powers to win the war; we can use them to fight the Depression, the misery, and suffering from which are equally great." This new approach embraced a number of initiatives. Unfortunately for the President, none proved especially effective. Just as important, with the presidential election approaching, the political heat generated by the Great Depression and the failure of Hoover's policies grew only more withering.[55]

In terms of the financial reform, since the recession, Hoover had been trying to repair the economy. He founded government agencies to encourage labor harmony and support local public works aid which promoted cooperation of government and business, stabilize prices, and strive to balance the budget. His work focused on indirect relief from state governments and the private sector, which was reflected in the letter emphasizing "more effective supporting for each national committee" and volunteer service -" appealing for funding" from outside the government.[56]

The commitment to maintain the gold standard system prevented the Federal Reserve expanded its money supply operations in 1930 and 1931, and it promoted Hoover's destructive balancing budgetary action to avoid the gold standard system overwhelming the dollar. As the Great Depression became worse, the call raised for increasing in federal intervention and spending. But Hoover refused to allow the federal government to force fixed prices, control the value of the business or manipulate the currency, in contrast, he started to control the dollar price. For official dollar prices, he expanded the credit base through free market operations in federal reserve system to ensure the domestic value of the dollar. He also tended to provide indirect aid to banks or local public works projects, refused to use federal funds to give aid to citizens directly, which he believed would lower public morale. Instead, he focused on volunteer fundraising to raise money for relief of the needy.[56]

Even though Hoover was a philanthropist before becoming president, his opponents regarded him as unconcerned about the plight of impoverished citizens. During the administration of Hoover, the US economic policies had moved to activism and interventionism. In his re-election campaign, Hoover tried to persuade Americans that direct monetary relief from the federal government would be devastating to the economy in the long run. However, this message was highly unpopular, and consequently Hoover was defeated by Franklin Roosevelt in the presidential election of 1932.[citation needed]

Roosevelt administration and the gold standard

At the beginning of 1933, during the last few weeks of Hoover's term, the American financial system was paralyzed. The Great Depression had been extended by the interventionist policy for four years. The bank crisis caused serious deflationary pressures. In fact, the worst period of 1932 – the Great Depression had passed, but the recovery was slow and weak. Roosevelt understood that traditional political and financial policy was not an adequate response to the crisis, and his administration chose to pursue the more radical measures of the New Deal.

During the financial crisis of 1933 culminating in the banking holiday of March 1933, gold had flowed out from the Fed in large quantities, to individuals and companies in the United States worried about bank failures, and to foreign entities worried about the depreciation of the dollar.[57]

In the spring and summer of 1933, the Roosevelt administration and the Congress took several actions that effectively suspended the gold standard. Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, and thirty-six hours later, he declared a nationwide bank moratorium in order to prevent a run on the banks by consumers lacking confidence in the economy. He also forbade banks to pay out gold or to export it.

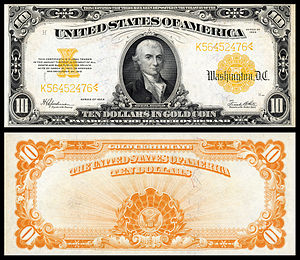

On March 9, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act, giving the President the power to control international and domestic gold exports. It also gave the treasury secretary the power to surrender of gold coins and certificates.

On April 5, Roosevelt ordered all gold coins and gold certificates in denominations of more than $100 turned in for other money. It required all persons to deliver all gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates owned by them to the Federal Reserve by May 1 for the set price of $20.67 per ounce. By May 10, the government had taken in $300 million of gold coin and $470 million of gold certificates.

On April 20, President Roosevelt issued a formal proclamation prohibiting gold exports and prohibiting the conversion of money and deposits into gold coins and ingots.

On May 12, the United States weakened the monetary connection with gold further when FDR signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act. Title III of this act, also known as the Thomas amendment, gave the President power to reduce the dollar's gold content by as much as 50%. President Roosevelt also used the silver standard instead of gold to exchange dollars, it determined by the price of the bank.[57]

On June 5, Congress enacted a joint resolution nullifying the clauses in many public and private obligations that permitted creditors to demand repayment in gold.

In 1934, the government price of gold was increased to $35 per ounce, effectively increasing the gold on the Federal Reserve's balance sheets by 69 percent. This increase in assets allowed the Federal Reserve to further inflate the money supply. The abandonment of the gold standard made the Wall Street stock prices quickly increase; Wall Street's stock trading was exceptionally active.

Political responses of the depression era

Hoover's response

The Hoover Administration attempted to correct the economic situation quickly, but was unsuccessful. Throughout Hoover's presidency, businesses were encouraged to keep wage rates high.[58] President Hoover and many academics believed that high wage rates would maintain a steady level of purchasing power, keeping the economy turning. In December 1929, after the beginning phases of the depression had begun, President Hoover continued to promote high wages. It wasn't until 1931 that business owners began reducing wages in order to stay afloat. Later that year, The Hoover Administration created the Check Tax[59] to generate extra government funding. The tax added a two-cent tax to the purchase of all bank checks, directly affecting the common man. This additional cost pushed people away from using checks, so instead, the majority of the population increased their usage of cash. Banks had already closed due to cash shortage, but this reaction to the Check Tax rapidly increased the pace.

Roosevelt's New Deal

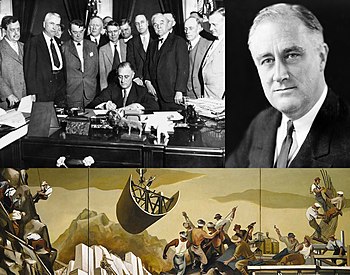

In the "First New Deal" of 1933–34, a wide variety of programs were targeted toward the depression and agriculture in rural areas, in the banking industry, and for the economy as a whole. Relief programs were set up for the long-term unemployed who are routinely passed over whenever new jobs did open up.[60][61] The most popular program was the Civilian Conservation Corps that put young men to work in construction jobs, especially in rural areas. Prohibition was repealed, fulfilling a campaign pledge and generating new tax revenues for local and state governments. A series of relief programs were designed to provide jobs, in cooperation with local governments.

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) sought to stimulate demand and provide work and relief through increased government spending. To end deflation the gold standard was suspended and a series of panels comprising business leaders in each industry set regulations that ended what was called "cut-throat competition", believed to be responsible for forcing down prices and profits nationwide.[62] Several Hoover agencies were continued, most notably the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which provided large-scale financial aid to banks, railroads, and other agencies.[63] Reforms that had never been enacted in the 1920s now took center stage, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) designed to electrify and modernize a very poor, mountainous region in Appalachia.

Top right: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was responsible for initiatives and programs are collectively known as the New Deal.

Bottom: a public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal.

In 1934–36 came the much more controversial "Second New Deal". It featured Social Security; the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a very large relief agency for the unemployed run by the federal government; and the National Labor Relations Board, which operated as a strong stimulus to the growth of labor unions. Unemployment fell by ⅔ in Roosevelt's first term (from 25% to 9%, 1933–1937). The second set of reforms launched by the Roosevelt administration during the same period included the Social Security Act of 1935. Insurance and poor relief ("public assistance" or "welfare") are constituent parts of the legislation, which provided pensions to the aged, benefit payments to dependent mothers, crippled children and blind people, and unemployment insurance.[64] The Social Security Act still plays a significant role of the American health and human service system so far. Much of the economy had recovered by 1936, but persistent, long-term unemployment lasted until rearmament began for World War II in 1940.[65]

The New Deal was, and still is, sharply debated.[66] The business community, with considerable support from such conservative Democrats as Al Smith, launched a crusade against the New Deal, warning that a dangerous man had seized control of the economy and threatened America's conservative traditions.[67] Scholars remain divided as well. When asked whether "as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression," 74% of American university professors specializing in economic history disagreed, 21% agreed with provisos, and 6% fully agreed. Among respondents who taught or studied economic theory, 51% disagreed, 22% agreed with provisos, and 22% fully agreed.[68]

Recession of 1937–1938

By 1936, all the main economic indicators had regained the levels of the late 1920s, except for unemployment, which remained high. In 1937, the American economy unexpectedly fell, lasting through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. Unemployment jumped from 14.3% in 1937 to 19.0% in 1938.[69] A contributing factor to the Recession of 1937 was a tightening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. The Federal Reserve doubled reserve requirements between August 1936 and May 1937[70] leading to a contraction in the money supply.

The Roosevelt administration reacted by launching a rhetorical campaign against monopoly power, which was cast as the cause of the depression, and appointing Thurman Arnold to break up large trusts; Arnold was not effective, and the campaign ended once World War II began and corporate energies had to be directed to winning the war.[71] By 1939, the effects of the 1937 recession had disappeared. Employment in the private sector recovered to the level of the 1936 and continued to increase until the war came and manufacturing employment leaped from 11 million in 1940 to 18 million in 1943.[72]

Another response to the 1937 deepening of the Great Depression had more tangible results. Ignoring the pleas of the Treasury Department, Roosevelt embarked on an antidote to the depression, reluctantly abandoning his efforts to balance the budget and launching a $5 billion spending program in the spring of 1938 in an effort to increase mass purchasing power.

Business-oriented observers explained the recession and recovery in very different terms from the Keynesian economists. They argued the New Deal had been very hostile to business expansion in 1935–37. They said it had encouraged massive strikes which had a negative impact on major industries and had threatened anti-trust attacks on big corporations. But all those threats diminished sharply after 1938. For example, the antitrust efforts fizzled out without major cases. The CIO and AFL unions started battling each other more than corporations, and tax policy became more favorable to long-term growth.[73]

On the other hand, according to economist Robert Higgs, when looking only at the supply of consumer goods, significant GDP growth only resumed in 1946. (Higgs does not estimate the value to consumers of collective goods like victory in war.[74]) To Keynesians, the war economy showed just how large the fiscal stimulus required to end the downturn of the Depression was, and it led, at the time, to fears that as soon as America demobilized, it would return to Depression conditions and industrial output would fall to its pre-war levels. The incorrect prediction by Alvin Hansen and other Keynesians that a new depression would start after the war failed to take account of pent-up consumer demand as a result of the Depression and World War.[75]

Afterward

The government began heavy military spending in 1940, and started drafting millions of young men that year.[76] By 1945, 17 million had entered service to their country, but that was not enough to absorb all the unemployed. During the war, the government subsidized wages through cost-plus contracts. Government contractors were paid in full for their costs, plus a certain percentage profit margin. That meant the more wages a person was paid the higher the company profits since the government would cover them plus a percentage.[77]

Using these cost-plus contracts in 1941–1943, factories hired hundreds of thousands of unskilled workers and trained them, at government expense. The military's own training programs concentrated on teaching technical skills involving machinery, engines, electronics and radio, preparing soldiers and sailors for the post-war economy.[78]

Structural walls were lowered dramatically during the war, especially informal policies against hiring women, minorities, and workers over 45 or under 18. In 1941, Executive Order 8802 banned racial discrimination in war-related employment, and set up the Fair Employment Practices Commission to enforce this. Strikes (except in coal mining) were sharply reduced as unions pushed their members to work harder. Tens of thousands of new factories and shipyards were built, with new bus services and nursery care for children making them more accessible. Wages soared for workers, making it quite expensive to sit at home. Employers retooled so that unskilled new workers could handle jobs that previously required skills that were now in short supply. The combination of all these factors drove unemployment below 2% in 1943.[79]

Roosevelt's declining popularity in 1938 was evident throughout the US in the business community, the press, and the Senate and House. Many were labeling the recession the "Roosevelt Recession". In late December 1938, Roosevelt looked to gain popularity with the American people, and try to regain the nation's confidence in the economy. His decision that December to name Harry Hopkins as Secretary of Commerce was an attempt to achieve the confidence he so badly needed. The appointment came as a surprise to most because of Hopkins' lack of business experience, but proved to be vastly important in shaping the years following the recession.[80]

Hopkins made it his mission to strengthen ties between the Roosevelt administration and the business community. While Roosevelt believed in complete reform through the New Deal, Hopkins took a more administrative position;[clarification needed] he felt that recovery was imperative and that The New Deal would continue to hinder recovery. With support from Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr, popular support for recovery, rather than reform, swept the nation. By the end of 1938 reform had been struck down, as no new reform laws were passed.[80]

The economy in America was now beginning to show signs of recovery and the unemployment rate was lowering following the abysmal year of 1938. The biggest shift towards recovery, however, came with the decision of Germany to invade France in May 1940. After France had been defeated in June, the U.S. economy would skyrocket in the months following. France's defeat meant that Britain and other allies would look to the U.S. for large supplies of materials for the war.[81]

The need for these war materials created a huge spurt in production, thus leading to a promising level of employment in America. Moreover, Britain chose to pay for their materials in gold. This stimulated the gold inflow and raised the monetary base, which in turn, stimulated the American economy to its highest point since the summer of 1929 when the depression began.[81]

By the end of 1941, before American entry into the war, defense spending and military mobilization had started one of the greatest booms in American history thus ending the last traces of unemployment.[81]

Facts and figures

Effects of depression in the U.S.:[82]

- 13 million people became unemployed. In 1932, 34 million people belonged to families with no regular full-time wage earner.[83]

- Industrial production fell by nearly 45% between 1929 and 1932.

- Homebuilding dropped by 80% between the years 1929 and 1932.

- In the 1920s, the banking system in the U.S. was about $50 billion, which was about 50% of GDP.[84]

- From 1929 to 1932, about 5,000 banks went out of business.

- By 1933, 11,000 of US 25,000 banks had failed.[85]

- Between 1929 and 1933, U.S. GDP fell around 30%; the stock market lost almost 90% of its value.[86]

- In 1929, the unemployment rate averaged 3%.[87]

- In Cleveland, the unemployment rate was[when?] 50%; in Toledo, Ohio, 80%.[83]

- One Soviet trading corporation in New York averaged 350 applications a day from Americans seeking jobs in the Soviet Union.[88]

- Over one million families lost their farms between 1930 and 1934.[83]

- Corporate profits dropped from $10 billion in 1929 to $1 billion in 1932.[83]

- Between 1929 and 1932, the income of the average American family was reduced by 40%.[89]

- Nine million savings accounts were wiped out between 1930 and 1933.[83]

- 273,000 families were evicted from their homes in 1932.[83]

- There were two million homeless people migrating around the country.[83]

- Over 60% of Americans were categorized as poor by the federal government in 1933.[83]

- In the last prosperous year (1929), there were 279,678 immigrants recorded, but in 1933 only 23,068 came to the U.S.[90][91]

- In the early 1930s, more people emigrated from the United States than immigrated to it.[92]

- With little economic activity there was scant demand for new coinage. No nickels or dimes were minted in 1932–33, no quarter dollars in 1931 or 1933, no half dollars from 1930 to 1932, and no silver dollars in the years 1929–33.

- In 1932 deflation was 10.7 percent and real interest rate was 11.49 percent.[93]

- The U.S. government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands, including many U.S. citizens, were deported against their will. Altogether about 400,000 Mexicans were repatriated.[94]

- New York social workers reported that 25% of all schoolchildren were malnourished. In the mining counties of West Virginia, Illinois, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania, the proportion of malnourished children was perhaps as high as 90%.[83]

- Many people became ill with diseases such as tuberculosis (TB).[83]

- The 1930 U.S. Census determined the U.S. population to be 122,775,046. About 40% of the population was under 20 years old.[95]

- Suicide rates increased; however, life expectancy increased from about 57 years in 1929 to 63 in 1933.[96]

See also

- Causes of the Great Depression

- New Deal coalition

- Entertainment during the Great Depression

- Great Contraction

- Penny auction (foreclosure)

- Timeline of the Great Depression

- Ham and Eggs Movement, California pension plan, 1938–40

- Great Depression in Washington State Project

- Strikes in the United States in the 1930s

General:

References

- ^ Gordon, John Steele. "10 Moments That Made American Business". American Heritage. No. February/March 2007. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Chandler, Lester V. (1970). America's Greatest Depression 1929–1941. New York, Harper & Row.

- ^ Chandler (1970); Jensen (1989); Mitchell (1964)

- ^ The Migrant Experience Archived October 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Memory.loc.gov (April 6, 1998). Retrieved on 2013-07-14.

- ^ American Exodus The Dust Bowl Mi Archived February 28, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved on July 14, 2013.

- ^ Bordo, Michael D.; Goldin, Claudia; White, Eugene N., eds. (1998). The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06589-2.

- ^ a b Robert Fuller (2012), Phantom of Fear: The Banking Panic of 1933, pp. 241–42 fn. 45

- ^ a b Milton Friedman; Anna Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691137940. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ Ben S. Bernanke (Nov. 8, 2002), FederalReserve.gov: "Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke" Archived 2020-03-24 at the Wayback Machine Conference to Honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago

- ^ "The Economic Causes and Impacts of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 (Fall 2012) – Historpedia". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "What caused the Wall Street Crash of 1929?". Economics Help. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "Banking Panics (1930–1933)." Encyclopedia of the Great Depression. Encyclopedia.com. June 13, 2017<http://www.encyclopedia.com Archived January 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine>.

- ^ USA annual GDP from 1910–60, in billions of constant 2005 dollars, with the years of the Great Depression (1929–1939) highlighted. Based on data from: Louis D. Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson, "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?" MeasuringWorth, 2008

- ^ Walter, John R. "Failures: The Great Contagion or the Great Shakeout?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly Volume 91/1 Winter 2005 91.1 (2005): 39–41. Web. 2005

- ^ (Federal Reserve Board 1933, 63–65).

- ^ Federal Reserve Board 1933, 67.

- ^ Walter, John R. "Failures: The Great Contagion or the Great Shakeout?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly Volume 91/1 Winter 2005 91.1 (2005): 39–53. Web. May 21, 2017.

- ^ Richardson, Gary. "Banking Panics of 1930–31". Federal Reserve History. N.p., November 22, 2013. Web. June 13, 2017

- ^ Walter, John R. "Failures: The Great Contagion or the Great Shakeout?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly Volume 91/1 Winter 2005 91.1 (2005): 45–46. Web. 2005

- ^ Hans Kaltenborn, It Seems Like Yesterday (1956) p. 88

- ^ Smiley, Gene. "Recent Unemployment Rate Estimates for the 1920s and 1930s" (PDF). wisc.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Richard J. Jensen, "The causes and cures of unemployment in the Great Depression." Journal of Interdisciplinary History (1989): 553–583 in JSTOR Archived March 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine; online copy Archived April 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Janet Poppendieck, Breadlines knee-deep in wheat: Food assistance in the Great Depression (2014)

- ^ Roger Biles, Big City Boss in Depression and War: Mayor Edward J. Kelly of Chicago (1984).

- ^ Mason B. Williams, City of Ambition: FDR, LaGuardia, and the Making of Modern New York (2013)

- ^ Richard Jensen, "The cities reelect Roosevelt: Ethnicity, religion, and class in 1940." Ethnicity. An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Study of Ethnic Relations (1981) 8#2: 189–195.

- ^ Jon C. Teaford, The twentieth-century American city (1986) pp. 90–96.

- ^ Roger W. Lotchin, The Bad City in the Good War: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego (2003)

- ^ Robert Whaples and Randall E. Parker, ed. (2013). Routledge Handbook of Modern Economic History. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-0415677042. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ Price V. Fishback, Michael R. Haines, and Shawn Kantor, "Births, deaths, and New Deal relief during the Great Depression." The Review of Economics and Statistics 89.1 (2007): 1–14, citing page online Archived March 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Orleck, Annelise (1993). ""We Are That Mythical Thing Called the Public": Militant Housewives during the Great Depression". Feminist Studies. 19 (1): 147–172. doi:10.2307/3178357. ISSN 0046-3663. JSTOR 3178357.

- ^ a b c Cohen, Lizabeth (2003). A Consumer's Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption. Vintage Books. ISBN 9780375707377.

- ^ a b Abramovitz, Mimi (2001). "Learning from the History of Poor and Working-Class Women's Activism". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 577: 118–130. doi:10.1177/000271620157700110. ISSN 0002-7162. JSTOR 1049827.

- ^ Glickman, Lawrence B. (2005). "'Make Lisle the Style': The Politics of Fashion in the Japanese Silk Boycott, 1937-1940". Journal of Social History. 38 (3): 573–608. doi:10.1353/jsh.2005.0032. ISSN 0022-4529. JSTOR 3790646.

- ^ Clark Hine, Darlene (Spring 2007). "African American Women and Their Communities in the Twentieth Century: The Foundation and Future of Black Women's Studies". Black Women, Gender + Families. 1 (1): 1–23. JSTOR 10.5406/blacwomegendfami.1.1.0001 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Kenneth L. Kusmer (2002). Down and Out, on the Road : The Homeless in American History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504778-3.

- ^ "Hoovervilles and Homelessness". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ Johnson, Roberta Ann (2010). "African Americans and Homelessness: Moving Through History". Journal of Black Studies. 40 (4): 583–605. doi:10.1177/0021934708315487. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 40648529.

- ^ a b c Reagan, Leslie J. (2022). When Abortion Was a Crime (2nd ed.). University of California Press. pp. 132–159. ISBN 978-0-520-38742-3.

- ^ a b c d Tone, Andrea (1996). "Contraceptive Consumers: Gender and the Political Economy of Birth Control in the 1930s". Journal of Social History. 29 (3): 485–506. doi:10.1353/jsh/29.3.485. JSTOR 3788942.

- ^ John A. Garraty, The Great Depression (1986)

- ^ Frank, Robert H.; Bernanke, Ben S. (2007). Principles of Macroeconomics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. p. 98.

- ^ Willard W. Cochrane, Farm prices: myth and reality (U of Minnesota Press, 1958)

- ^ League of Nations, World Economic Survey 1932–33 (1934) p. 43

- ^ Broadus Mitchell, Depression Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929–1941 (1947),

- ^ Garraty, Great Depression (1986) ch 1

- ^ Robert Skidelsky, "The Great Depression: Keynes´s Perspective," in: Elisabeth Müller-Luckner, Harold James, The Interwar Depression in an International Context," (2002) p. 99

- ^ Robert O. Paxton and Julie Hessler, Europe in the Twentieth Century (2011) ch 10–11

- ^ "Index numbers of employment as reported by employers in leading cities, as of the first of each month, January 1935 to December 1936, with yearly averages since 1922". Statistics Canada. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ "Index numbers of rates of wages for various classes of labour in Canada, 1913 to 1936". Statistics Canada. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Wardhaugh, Robert Alexander; Ferguson, Barry (2021). The Rowell-Sirois Commission and the Remaking of Canadian Federalism. Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press. p. 26.

- ^ Ralph Allen, Ordeal by Fire: Canada, 1910–1945 (1961), ch. 3, pp 37–39.

- ^ "History, Economic–Labour Policy–1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ^ Kindleberger, Charles P. (1978). The world in depression, 1929–1939.

- ^ "Herbert Hoover: Domestic Affairs | Miller Center". millercenter.org. 4 October 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ a b "Herbert Hoover on the Great Depression and New Deal, 1931–1933 | The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". gilderlehrman.org. July 24, 2013. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Richardson, Gary. "Roosevelt's Gold Program | Federal Reserve History". federalreservehistory.org. Archived from the original on May 15, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ Friedman, Milton; Schwartz, Anna Jacobson (1971). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691003542. Archived from the original on May 30, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ "The Great Depression and the Role of Government Intervention". Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ Eric Rauchway. The Great Depression and the New Deal: A Very Short Introduction (2008).

- ^ Aaron D. Purcell, ed. Interpreting American History: The New Deal and the Great Depression (2014).

- ^ Olivier Blanchard und Gerhard Illing, Makroökonomie, Pearson Studium, 2009, ISBN 978-3-8273-7363-2, pp. 696–97

- ^ James Stuart Olson, Saving Capitalism: The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the New Deal, 1933–1940 (2nd ed. 2017).

- ^ "The New Deal". Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ Broadus Mitchell, Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929–1941 (1964)

- ^ Parker, ed. Reflections on the Great Depression (2002)

- ^ Kim Phillips-Fein, Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal (2010).

- ^ Robert Whaples, "Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Mar. 1995), pp. 139–154 in JSTOR see also the summary at "EH.R: FORUM: The Great Depression". Eh.net. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ^ Kenneth D. Roose, The Economics of Recession and Revival: An Interpretation of 1937–38, (1969)

- ^ Stauffer, Robert F. (2002). "Another Perspective on the Reserve Requirement Increments of 1936 and 1937". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 25 (1): 161–179. doi:10.1080/01603477.2002.11051343. JSTOR 4538817. S2CID 154092343.

- ^ Gressley, Gene M. (1964). "Thurman Arnold, Antitrust, and the New Deal". The Business History Review. 38 (2): 214–231. doi:10.2307/3112073. JSTOR 3112073. S2CID 154882053.

- ^ Roose, Kenneth D. (1948). "The Recession of 1937–38". Journal of Political Economy. 56 (3): 239–248. doi:10.1086/256675. JSTOR 1825772. S2CID 154469310.

- ^ Gary Dean Best, Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933–1938 (1990) pp 175–216

- ^ Higgs, Robert (March 1992). "Wartime Prosperity? A Reassessment of the U.S. Economy in the 1940s". Journal of Economic History. 52 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1017/S0022050700010251. S2CID 154484756.

- ^ Theodore Rosenof, Economics in the Long Run: New Deal Theorists and Their Legacies, 1932–1993 (1997)

- ^ Great Depression and World War Michael Lewis Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Library of Congress.

- ^ Paul A. C. Koistinen, Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940–1945 (2004)

- ^ Jensen (1989); Edwin E. Witte, "What The War Is Doing to Us". Review of Politics. (Jan. 1943). 5(1): 3–25 JSTOR 1404621

- ^ Harold G. Vester. The U.S. Economy in World War III. (1988)

- ^ a b Smiley, Gene. Rethinking the Great Depression. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, publisher. 2002.

- ^ a b c Hall, Thomas E., and Ferguson, David J. "The Great Depression: An International Disaster of Perverse Economic Policies". Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1998. p. 155

- ^ "I remember the Wall Street Crash". BBC News. October 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Overproduction of Goods, Unequal Distribution of Wealth, High Unemployment, and Massive Poverty Archived February 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, From: President's Economic Council

- ^ Q&A: Lessons from the Great Depression Archived January 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, By Barbara Kiviat, TIME, January 6, 2009

- ^ "About the Great Depression". Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ The Great Depression: The sequel Archived March 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, By Cameron Stacy, salon.com, April 2, 2008

- ^ Economic Recovery in the Great Depression Archived September 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Frank G. Steindl, Oklahoma State University

- ^ A reign of rural terror, a world away Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. News, June 22, 2003

- ^ "American History – 1930–1939". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010.

- ^ Persons Obtaining Legal Permanent Resident Status in the United States of America Archived February 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Source: US Department of Homeland Security

- ^ The Facts Behind the Current Controversy Over Immigration[permanent dead link], by Allan L. Damon, American Heritage Magazine, December 1981

- ^ A Great Depression? Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, by Steve H. Hanke, Cato Institute

- ^ Vijayakumar, VK (May 4, 2020). "Deeper depression unlikely, expect U-shaped recovery post COVID-19". Moneycontrol. Archived from the original on May 4, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ^ The Great Depression and New Deal Archived March 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, by Joyce Bryant, Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

- ^ 1931 U.S Census Report Archived March 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Contains 1930 Census results

- ^ Tapia Granados, J. A.; Diez Roux, A. V. (September 28, 2009). "Life and death during the Great Depression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (41): 17290–17295. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10617290T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904491106. PMC 2765209. PMID 19805076.

Population health did not decline and indeed generally improved during the 4 years of the Great Depression, 1930–1933, with mortality decreasing for almost all ages, and life expectancy increasing by several years

Further reading

- Bernanke, Ben. Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton University Press, 2000) (Chapter One – "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression" Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine online)

- Best, Gary Dean. Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933–1938 (1991) ISBN 0-275-93524-8, a conservative viewpoint online

- Best, Gary Dean. The Nickel and Dime Decade: American Popular Culture during the 1930s. (1993) online

- Bindas, Kenneth J. Modernity and the Great Depression: The Transformation of American Society, 1930–1941 (UP of Kansas, 2017). 277 pp.

- Blumberg, Barbara. The New Deal and the Unemployed: The View from New York City (1977). online

- Bordo, Michael D., Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White, eds., The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (1998). Advanced economic history.

- Bremer, William W. "Along the American Way: The New Deal's Work Relief Programs for the Unemployed." Journal of American History 62 (December 1975): 636–652 online

- Cannadine, David (2007). Mellon: An American Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 395–469. ISBN 978-0679450320.

- Chandler, Lester. America's Greatest Depression (1970). overview by economic historian. online

- Cravens, Hamilton. Great Depression: People and Perspectives (2009), social history excerpt and text search

- Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression (2009) excerpt and text search

- Field, Alexander J. A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth (Yale University Press; 2011) 387 pages; argues that technological innovations in the 1930s laid the foundation for economic success in World War II and postwar

- Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963) ISBN 0-691-04147-4 classic monetarist explanation; highly statistical online

- Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz, The Great Contraction 1929–1933 (New Edition, 2008), chapter from A Monetary History covering Great Contraction

- Fuller, Robert Lynn, "Phantom of Fear" The Banking Panic of 1933 (2012)