Contents

The James–Younger Gang was a notable 19th-century gang of American outlaws that revolved around Jesse James and his brother Frank James. The gang was based in the state of Missouri, the home of most of the members.

Membership fluctuated from robbery to robbery, as the outlaws' raids were usually separated by many months. As well as the notorious James brothers, at various times it included the Younger brothers (Cole, Jim, John, and Bob), John Jarrett (married to the Youngers' sister Josie), Arthur McCoy, George Shepherd, Oliver Shepherd, William McDaniel, Tom McDaniel, Clell Miller, Charlie Pitts, William Chadwell (alias Bill Stiles), and Matthew "Ace" Nelson.

The James–Younger Gang had its origins in a group of Confederate bushwhackers that participated in the bitter partisan fighting that wracked Missouri during the American Civil War. After the war, the men continued to plunder and murder, though the motive shifted to personal profit rather than in the name of the Confederacy. The loose association of outlaws did not truly become the "James–Younger Gang" until 1868 at the earliest, when the authorities first named Cole Younger, John Jarrett, Arthur McCoy, George Shepherd and Oliver Shepherd as suspects in the robbery of the Nimrod Long bank in Russellville, Kentucky.

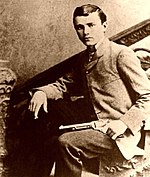

The James–Younger Gang dissolved in 1876, following the capture of the Younger brothers in Minnesota during the unsuccessful attempt to rob the Northfield First National Bank. Three years later, Jesse James organized a new gang, including Clell Miller's brother Ed and the Ford brothers (Robert and Charles), and renewed his criminal career. This career came to an end in 1882 when Robert Ford shot Jesse James from behind, killing him.

For nearly a decade following the Civil War, the James–Younger Gang was among the most feared, most publicized, and most wanted confederations of outlaws on the American frontier. Though their crimes were reckless and brutal, many members of the gang commanded a notoriety in the public eye that earned the gang significant popular support and sympathy. The gang's activities spanned much of the central part of the country; they are suspected of having robbed banks, trains, and stagecoaches in at least eleven states: Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, and West Virginia.

History

Origins

From the beginning of the American Civil War, the state of Missouri had chosen not to secede from the Union but neither to fight for it nor against it either: its position, as determined by an 1861 constitutional convention, was officially neutral. Missouri, however, had been the scene of much of the agitation leading up to the outbreak of the war, and was home to dedicated partisans from both sides. In the mid-1850s, local Unionists and Secessionists had begun to battle each other throughout the state, and by the end of 1861, guerrilla warfare erupted between Confederate partisans known as "bushwhackers" and the more organized Union forces. The Missouri State Guard and the newly elected Governor of Missouri, Claiborne Fox Jackson, who maintained implicit Southern sympathies, were forced into exile as Union troops under Nathaniel Lyon and John C. Frémont took control of the state. Still, pro-Confederate guerrillas resisted; by early 1862, the Unionist provisional government mobilized a state militia to fight the increasingly organized and deadly partisans. This conflict (fought largely, though not exclusively, between Missourians themselves) raged until after the fall of Richmond and the surrender of General Robert E. Lee, costing thousands of lives and devastating broad swathes of the Missouri countryside.

The conflict rapidly escalated into a succession of atrocities committed by both sides. Union troops often executed or tortured suspects without trial and burned the homes of suspected guerrillas and those suspected of aiding or harboring them. Where credentials were suspect, the accused guerrilla was often executed, as in the case of Lt. Col. Frisby McCullough after the Battle of Kirksville. Bushwhackers, meanwhile, frequently went house to house, executing Unionist farmers.

The James and Younger brothers belonged to families from an area known as "Little Dixie" in western Missouri with strong ties to the South. Zerelda Samuel, the mother of Frank and Jesse James, was an outspoken partisan of the South, though the Youngers' father, Henry Washington Younger, was believed to be a Unionist. Cole Younger's initial decision to fight as a bushwhacker is usually attributed to the death of his father at the hands of Union forces in July 1862. He and Frank James fought under one of the most famous Confederate bushwhackers, William Clarke Quantrill, though Cole eventually joined the regular Confederate Army. Jesse James began his guerrilla career in 1864, at the age of sixteen, fighting alongside Frank under the leadership of Archie Clement and "Bloody Bill" Anderson.

At the war's end, Frank James surrendered in Kentucky; Jesse James attempted to surrender to Union militia but was shot through the lung outside of Lexington, Missouri.[1] He was nursed back to health by his cousin, Zerelda "Zee" Mimms, whom he eventually married. When Cole Younger returned from a mission to California, he learned that Quantrill and Anderson had both been killed. The James brothers, however, continued to associate with their old guerrilla comrades, who remained together under the leadership of Archie Clement. It was likely Clement who, amid the tumult of Reconstruction in Missouri, turned the guerrillas into outlaws.

Early years: 1866 to 1870

On February 12, 1866, a group of gunmen carried out one of the first daylight, peacetime, armed bank robberies in U.S. history when they held up the Clay County Savings Association in Liberty, Missouri. The outlaws stole some $60,000 in cash and bonds and killed a bystander named George Wymore on the street outside the bank.[2] State authorities suspected Archie Clement of leading the raid, and promptly issued a reward for his capture. In later years, the list of suspects grew to include Jesse[3] and Frank James, Cole Younger, John Jarrett, Oliver Shepherd, Bud and Donny Pence, Frank Greg, Bill and James Wilkerson, Joab Perry, Ben Cooper, Red Mankus, and Allen Parmer (who later married Susan James, Frank and Jesse's sister).

Four months later, on June 13, 1866, two members of Quantrill's Raiders were freed from prison in Independence, Missouri; the jailer, Henry Bugler, was killed. The James brothers are believed to have been involved.[4] The gang began a string of robberies, many of which were linked to Clement's group of bushwhackers. The hold-up most clearly linked to the group was of Alexander Mitchell and Company in Lexington, Missouri, on October 30, 1866, which netted $2,011.50. Clement was also linked to violence and intimidation against officials of the Republican government that now held power in the state. On election day, Clement led his men into Lexington, where they drove Republican voters away from the polls, thereby securing a Republican defeat. A detachment of state militiamen was dispatched to the town. They convinced the bushwhackers to disperse, then attempted to capture Clement, who still had a price on his head. Clement refused to surrender and was shot down in a wild gunfight on the streets of Lexington.

Despite the death of Clement, his old followers remained together, and robbed a bank across the Missouri River from Lexington in Richmond, Missouri, on May 22, 1867, in which the town mayor John B. Shaw and two lawmen [Barry and George Griffin] were killed.[5] This was followed on March 20, 1868, by a raid on the Nimrod Long bank in Russellville, Kentucky. In the aftermath of the two raids, however, the more senior bushwhackers were killed, captured or simply left the group. This set the stage for the emergence of the James and Younger brothers, and the transformation of the old crew into the James–Younger Gang. John Jarrett and Arthur McCoy were mentioned in numerous newspaper accounts, so they were likely active in gang activities up to 1875.[citation needed]

On December 7, 1869, Frank and Jesse James are believed to have robbed the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin, Missouri.[6] Jesse is suspected of having shot down the cashier, John W. Sheets,[7] in the mistaken belief that he was Samuel P. Cox, the Union militia officer who had ambushed and killed "Bloody Bill" Anderson during the Civil War. The James brothers were unknown up to this point; this may have been their first robbery.[citation needed] Their names were later added to previous robberies as an afterthought.

1871 to 1873

John Younger was almost arrested in Dallas County, Texas in January 1871. He killed two lawmen [Nichols and Mcmahan] during the attempt and escaped.[8][9] On June 3, 1871, the gang robbed a bank in Corydon, Iowa; the James and Younger brothers were suspects. The bank contacted the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in Chicago, the first involvement of the famous agency in the pursuit of the James–Younger Gang. Agency founder Allan Pinkerton dispatched his son, Robert Pinkerton, who joined a county sheriff in tracking the gang to a farm in Civil Bend, Missouri. A short gunfight ended indecisively as the gang escaped. On June 24, Jesse James wrote a letter to the Kansas City Times, claiming Republicans were persecuting him for his Confederate loyalties by accusing him and Frank of carrying out the robberies. "But I don't care what the degraded Radical party thinks about me," he wrote, "I would just as soon they would think I was a robber as not."

On April 29, 1872, the gang robbed a bank in Columbia, Kentucky. One of the outlaws shot the cashier, R. A. C. Martin, who had refused to open the safe. On September 23, 1872, three men (identified by former bushwhacker Jim Chiles as Jesse James and Cole and John Younger) robbed a ticket booth of the Second Annual Kansas City Industrial Exposition, amid thousands of people. They took some $900, and accidentally shot a little girl in the ensuing struggle with the ticket-seller. Apart from Chiles' testimony, there is no other evidence this crime was committed by the James or Younger brothers, and Jesse later wrote a letter denying his or the Youngers' involvement. Cole was furious over this, because neither he nor brother John had been linked to the crime before the letter. The crime was praised by Kansas City Times editor John Newman Edwards in a famous editorial entitled, "The Chivalry of Crime." Edwards soon published an anonymous letter from one of the outlaws (believed to be Jesse) that referred to the approaching presidential election: "Just let a party of men commit a bold robbery, and the cry is hang them. But [President Ulysses S.] Grant and his party can steal millions and it is all right," the outlaw wrote. "They rob the poor and rich, and we rob the rich and give to the poor."

On May 27, 1873, the James–Younger Gang robbed the Ste. Genevieve Savings Association in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. As they rode off they fired in the air and shouted, "Hurrah for Hildebrand!" Samuel S. Hildebrand was a famous Confederate bushwhacker from the area who had recently been shot dead in Illinois. Arthur McCoy had lived in this area and knew it quite well; he was likely involved and may have been the planner and leader.[citation needed]

On July 21, 1873, the gang carried out what was arguably the first train robbery west of the Mississippi River, derailing a locomotive of the Rock Island Railroad near Adair, Iowa. Engineer John Rafferty died in the crash. The outlaws took $2,337 from the express safe in the baggage car, having narrowly missed a transcontinental express shipment of a large amount of cash.

On November 24, John Newman Edwards published a lengthy glorification of the James brothers, Cole and John Younger, and Arthur McCoy, in a twenty-page special supplement to his newspaper the St. Louis Dispatch (Edwards had moved from the Kansas City Times to the Dispatch in 1873). Most of the supplement, entitled "A Terrible Quintet," was devoted to Jesse James, the gang's public face, and the article stressed their Confederate loyalties.

1874 to 1876

In January 1874, the outlaws were suspected of holding up a stagecoach in Bienville Parish, Louisiana. Later another suspected stage robbery took place between Malvern and Hot Springs, Arkansas. There, the gang returned a pocket watch to a Confederate veteran, saying that Northern men had driven them to outlawry and that they intended to make them pay for it. On January 31, the gang robbed a southbound train on the Iron Mountain Railway at Gads Hill, Missouri. For the first of two times in all their train robberies, the outlaws robbed the passengers. In both train robberies, their usual target, the safe in the baggage car belonging to an express company, held an unusually small amount of money. On this occasion, the outlaws reportedly examined the hands of the passengers to ensure that they did not rob any working men. Many newspapers reported this was actually done by the "Arthur McCoy" gang. To correct errors, the gang telegraphed a report of the Gads Hill robbery to the St. Louis Dispatch newspaper for publication.[10]

The Adams Express Company, which owned the safe robbed at Gads Hill, hired the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. On March 11, 1874, Joseph W. Whicher, the agent who was sent to investigate the James brothers, was found shot to death alongside a rural road in Jackson County, Missouri.[11] Two other agents, John Boyle and Louis J. Lull, accompanied by Deputy Sheriff Edwin B. Daniels to track the Youngers, posed as cattle buyers. On March 17, 1874, the trio was stopped and attacked by John and Jim Younger on a rural stretch of road near Monegaw Springs, Missouri. Daniels was killed instantly,[12] Lull and John Younger shot and killed each other, while Boyle and Jim Younger escaped.[13] Lull lived long enough to testify before a coroner's inquest before succumbing to his wounds a few days later.[14]

The Pinkerton deaths added to the growing embarrassment suffered by Missouri's first post-war Democratic governor, Silas Woodson. He issued a $2,000 reward offer for the Iron Mountain robbers (the reward usually offered for criminals was $300). He also persuaded the state legislature to provide $10,000 for a secret fund to track down the famous outlaws. The first agent, J. W. Ragsdale, was hired on April 9, 1874. On August 30, three of the gang held up a stagecoach across the Missouri River from Lexington, Missouri, in view of hundreds of onlookers on the bluffs of the town. A passenger identified two of the robbers as Frank and Jesse James. The acting governor, Charles P. Johnson, dispatched an agent selected from the St. Louis police department to investigate.

The gang was observed during this period by William Eleroy Curtis, a journalist-turned-hostage. Curtis interviewed his captors, who allowed him to send dispatches to the Chicago Inter-Ocean.[15][16]

The gang next robbed a train on the Kansas Pacific Railroad near Muncie, Kansas, on December 8, 1874. It was one of the outlaws' most successful robberies, gaining them $30,000. William "Bud" McDaniel was captured by a Kansas City police officer after the robbery, and later was shot during an escape attempt.

On the night of January 25, 1875, Pinkerton agents surrounded the James farm in Kearney, Missouri. Frank and Jesse James had been there earlier but had already left. When the Pinkertons threw an iron incendiary device into the house, it exploded when it rolled into a blazing fireplace. The blast nearly severed the right arm of Zerelda Samuel, the James boys' mother (the arm had to be amputated at the elbow that night), and killed their 9-year-old half-brother, Archie Samuel. On April 12, 1875, an unknown gunman shot dead Daniel Askew, a neighbor and former Union militiaman who may have been suspected of providing the Pinkertons with a base for their raid. Allan Pinkerton then abandoned the chase for the James–Younger Gang.

By September 1875, at least part of the gang had ventured east to Huntington, West Virginia, where they robbed a bank on September 7. Two new members participated: Tom McDaniel (brother of Bud) and Tom Webb (a Confederate veteran who had been at Lawrence with Frank and Cole). McDaniel was killed by a posse and Webb was caught. The other two robbers, Frank and Cole, escaped.

Also in 1875, the two James brothers moved to the outskirts of Nashville, Tennessee, probably to save their mother from further raids by detectives. Once there, Jesse James began to write letters to the local press, asserting his place as a Confederate hero and a martyr to Radical Republican vindictiveness.

On July 7, 1876, Frank and Jesse James, Cole and Bob Younger, Clell Miller, Charlie Pitts, Bill Chadwell and Hobbs Kerry robbed the Missouri Pacific Railroad at the "Rocky Cut" near Otterville, Missouri. The new man, Kerry, was arrested soon after and he readily identified his accomplices.

Northfield, Minnesota Raid

The Rocky Cut raid set the stage for the final act of the James–Younger Gang: the famous Northfield, Minnesota raid on September 7, 1876. The target was the First National Bank of Northfield, which was far outside the gang's usual territory. The idea for the raid came from Jesse and Bob Younger. Cole tried to talk his brother out of the plan, but Bob refused to back down. Reluctantly, Cole agreed to go, writing to his brother Jim in California to come home. Jim Younger had never wanted anything to do with Cole's outlaw activities, but he agreed to go out of family loyalty. The Northfield bank was not unusually rich. According to public reports, it was a perfectly ordinary rural bank, though rumors persisted that General Adelbert Ames, son of the owner of the Ames Mill in Northfield, had deposited $50,000 there.

Shortly after the robbery, Bob Younger declared that they had selected it because of its connection to two Union generals and Radical Republican politicians: Benjamin Butler and his son-in-law Adelbert Ames. General Ames had just stepped down as Governor of Mississippi, where he had been strongly identified with civil rights for freedmen. He had recently moved to Northfield, where his father owned the mill on the Cannon River and had a large amount of stock in the bank. One of the outlaws "had a spite" against Ames, Bob said. Cole Younger said much the same thing years later and recalled greeting "General Ames" on the street in Northfield just before the robbery.

Cole, Jim and Bob Younger, Frank and Jesse James, Charlie Pitts, Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell took the train to St. Paul, Minnesota, in early September 1876. After a layover in St. Paul they divided into two groups, one going to Mankato, the other to Red Wing, on either side of Northfield. They purchased expensive horses and scouted the terrain around the towns, agreeing to meet south of Northfield along the Cannon River near Dundas on the morning of September 7, 1876. The gang attempted to rob the bank about 2:00 p.m. on September 7. Northfield residents had seen the gang leave a local restaurant near the mill shortly after noon, where they dined on fried eggs. They testified at the Younger brothers' trial that the group smelled of alcohol and that the gang was obviously under the influence when they greeted General Ames.

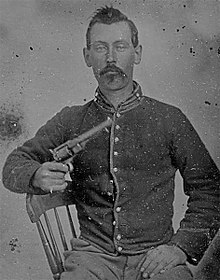

Three of the outlaws (Bob Younger, Frank James and Charlie Pitts) crossed the bridge by the Ames Mill and entered the bank; the other five (Jesse James, Cole and Jim Younger, Bill Stiles and Clell Miller) stood guard outside. Two were standing outside the bank’s front door and the other three were waiting in Mills Square to guard the gang's escape route. According to some reports, J. S. Allen shouted to the townspeople, “Get your guns, boys, they’re robbing the bank!” Once local citizens realized a robbery was in progress, several took up arms from local hardware stores. Shooting from behind cover, they poured deadly fire on the outlaws. During the gun battle, medical student Henry Wheeler killed Miller, shooting from a third-floor window of the Dampier House Hotel, across the street from the bank. Another civilian named A. R. Manning, who took cover at the corner of the Sciver building down the street, killed Stiles. Other civilians wounded the Younger brothers (Cole was shot in his left hip, Bob suffered a shattered elbow, and Jim was shot in the jaw). The only civilian fatality on the street was 30-year-old Nicholas Gustafson, an unarmed recent Swedish immigrant, who was killed by Cole Younger at the corner of 5th Street and Division.

Thirteen Swedish families lived west of Northfield in the Millersburg area in 1876, including Peter Gustafson, who had recently been joined by his brother Nicolaus and nephew Ernst from Sweden. West of Millersburg that morning, Peter Youngquist harnessed his mules and headed for Northfield to sell farm produce, accompanied by Gustafson and three others. The Swedes arrived in Northfield about 1:00 p.m. and set up their vegetable wagon along the Cannon River near 5th Street. About 2:00 p.m., they heard gunshots. Nicolaus Gustafson ran to the intersection of Division and 5th a block away, where he was shot in the head as the bank was being robbed. Gustafson died four days later. Another Swede named John Olson was an eyewitness to the Gustafson shooting and later testified against Cole Younger.

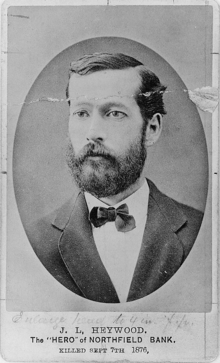

Inside the bank, the assistant cashier Joseph Lee Heywood refused to open the safe and was murdered for resisting. The two other employees in the bank were teller Alonzo Bunker and assistant bookkeeper Frank Wilcox. Bunker escaped from the bank by running out the back door despite being wounded in the right shoulder by Pitts as he ran. The three robbers then ran out of the bank after hearing the shooting outside and mounted their horses to make a run for it, having taken only several bags of nickels from the bank. Every year in September, Northfield hosts "Defeat of Jesse James Days", a celebration of the town's victory over the James–Younger Gang.

In addition to the death of Miller and Stiles, every one of the rest of the gang was wounded, including Frank James and Pitts, both shot in their right legs. Jesse James was the last one to be shot, taking a bullet in the thigh as the gang escaped. The six surviving outlaws rode out of town on the Dundas Road toward Millersburg where four of them had spent the night before.

Aftermath

Minnesotans joined posses and set up picket lines by the hundreds. After several days the gang had only reached the western outskirts of Mankato when they decided to split up (despite persistent stories to the contrary, Cole Younger told interviewers that they all agreed to the decision). The Youngers and Pitts remained on foot, moving west, until finally they were cornered in a swamp called Hanska Slough, just south of La Salle, Minnesota, on September 21, two weeks after the Northfield raid. In the gunfight that followed, Pitts was killed and the Youngers were again wounded. The Youngers surrendered and pleaded guilty to murder in order to avoid execution. Frank and Jesse secured horses and fled west across southern Minnesota, turning south just inside the border of the Dakota Territory. In the face of hundreds of pursuers and a nationwide alarm, Frank and Jesse escaped, but the infamous James–Younger Gang was no more.

On September 23, 1876, the Younger brothers were taken to the Rice County jail in Faribault. On November 16, a grand jury issued four indictments—one each for the first-degree murders of Joseph Heywood and Nicolaus Gustafson, one for bank robbery, and one for assault with deadly weapons on the wounded bank clerk, Bunker. The three brothers pleaded guilty on November 20, 1876, and were sentenced to life terms in the Minnesota Territorial Prison at Stillwater.

Nicolaus Gustafson was buried in Northfield because the Millersburg Swedes had no cemetery in 1876. After his death, the Millersburg Swedes determined to establish their own church and burial ground. Peter Youngquist and Carl Hirdler donated an acre of land adjacent to their homes overlooking Circle Lake and in 1877 John Olson was hired to build the Christdala Evangelical Swedish Lutheran Church 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Millersburg. Today the church is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and historical markers in front of the church tell the story of Nicolaus Gustafson and the founding of Christdala.

Final years

Having escaped, Frank James joined Jesse in Nashville, Tennessee, where they spent the next three years living peacefully. Frank in particular seemed to have thrived in his new life farming in the Whites Creek area. Jesse did not adapt well to peace; he gathered up recruits, formed a new gang and returned to a life of crime. On October 8, 1879, Jesse and his gang robbed the Chicago and Alton Railroad near Glendale, in Jackson County, Missouri. Unfortunately for Jesse, one of the men, Tucker Basham, was captured by a posse. He told authorities he had been recruited by Bill Ryan.[citation needed]

On September 3, 1880, Jesse James and Bill Ryan robbed a stagecoach near Mammoth Cave, Kentucky. On October 5, 1880, they robbed the store of John Dovey in Mercer, Kentucky. On March 11, 1881, Jesse, Ryan, and Jesse's cousin Wood Hite robbed a federal paymaster at Muscle Shoals, Alabama, taking $5,240.[17] Shortly afterward, a drunk and boastful Ryan was arrested in Whites Creek, near Nashville, and both Frank and Jesse James fled back to Missouri.[citation needed]

On July 15, 1881, Frank and Jesse James, Wood and Clarence Hite, and Dick Liddil robbed the Rock Island Railroad near Winston, Missouri, of $900. Train conductor William Westfall and passenger John McCullough were killed.[18][19] On September 7, 1881, Jesse James carried out his last train robbery, holding up the Chicago and Alton Railroad. The gang held up the passengers when the express safe proved to be nearly empty.

With this new outbreak of train robberies, the new Governor of Missouri, Thomas T. Crittenden, convinced the state's railroad and express executives to put up the money for a large reward for the capture of the James brothers. Creed Chapman and John Bugler were arrested for participating in the robbery on September 7, 1881. Though they were confirmed as having participated in the robbery by convicted members of the gang, neither was ever convicted.

In December 1881, Wood Hite was killed by Liddil in an argument over Martha Bolton, the sister of the Fords.[20] Bob Ford, not yet a member of the gang, assisted Liddil in his gunfight. Ford and Liddil, with Bolton as an intermediary, made deals with Governor Crittenden. On February 11, 1882, James Timberlake arrested Wood Hite's brother Clarence, who made a confession but died of tuberculosis in prison. Ford, on the other hand, agreed to bring down Jesse James in return for the reward.[citation needed]

On April 3, 1882, Ford fatally shot Jesse James behind the ear at James's rented apartment in St. Joseph, Missouri.[21][22] Bob and his brother Charley surrendered to the authorities, pleaded guilty, and were promptly pardoned by Crittenden. On October 4, 1882, Frank James surrendered to Crittenden. Accounts say that Frank surrendered with the understanding that he would not be extradited to Northfield, Minnesota.[23] Only two cases ever came to trial: one in Gallatin, Missouri, for the July 15, 1881, robbery of the Rock Island Line train at Winston, Missouri in which a train crewman and a passenger were killed, and one in Huntsville, Alabama, for the March 11, 1881, robbery of a United States Army Corps of Engineers payroll at Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Frank James was found not guilty by juries in both cases (July 1883 at Gallatin and April 1884 at Huntsville). Missouri kept jurisdiction over him with other charges but they never came to trial and they kept him from being extradited to Minnesota. Frank James died on February 8, 1915, at the age of 72.[24]

The Youngers remained loyal to the Jameses when they were in prison and never informed on them. They ended up being model prisoners and in one incident helped keep other prisoners from escaping during a fire at the prison. Cole Younger also founded the longest-running prison newspaper in the United States during his stay at the Minnesota Territorial Prison in Stillwater.[citation needed] Bob Younger died in prison of tuberculosis on September 15, 1889, at the age of 36. After much legal dispute, Cole and Jim Younger were paroled in 1901 on the condition they remain in Minnesota. Jim committed suicide on October 19, 1902, while on parole in St. Paul, at the age of 54. Cole Younger received a pardon in 1903 on the condition that he leave Minnesota and never return. He traveled to Missouri where he joined a "Wild West" show with Frank James and died there on March 21, 1916, at the age of 72.[25]

Legacy

Bill Ayers and Diana Oughton headed a splinter group of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) that called itself the "Jesse James Gang" and evolved into the Weather Underground.[26]

In popular culture

See also

Film

- The James Boys in Missouri (1908)[27]

- The Younger Brothers (1908)[28]

- Jesse James (1939)

- Days of Jesse James (1939)

- Bad Men of Missouri (1941)

- Jesse James at Bay (1941)

- The Younger Brothers (1949)

- Kansas Raiders (1950)

- The Great Missouri Raid (1951)

- The True Story of Jesse James (1957)

- Young Jesse James (1960)

- The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (1972)

- The Long Riders (1980)

- Frank and Jesse (1994)

- American Outlaws (2001)

- The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007)[29]

Literature

- The James and Younger brothers are major characters in Wildwood Boys (William Morrow, 2000; New York), a biographical novel of "Bloody Bill" Anderson by James Carlos Blake

- The Story of Cole Younger, by Himself (Cole Younger, 1903; Chicago)

See also

References

- ^ Wellman Jr., Paul I; Brown, Richard Maxwell (April 1986). A Dynasty of Western Outlaws. University of Nebraska Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0803297098.

- ^ National Historical Company (1885). History of Clay and Platte Counties, Missouri. St. Louis, Missouri: Press of Nixon-Jones Printing Co. pp. 259–260.

- ^ "Clay County Savings Association Bank Liberty, Missouri". The James–Younger Gang: Come Ride With Us. Archived from the original on 22 December 1996. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Jailer Henry Bugler". ODMP Remembers... The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ "Barry G. Griffin". ODMP Remembers... The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ Darryl (12 July 2008). "Eye-Witness Account of 1869 Bank Robbery". Daviess County Historical Society. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ John W Sheets

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff Charles H. Nichols". ODMP remembers... The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff James McMahan". ODMP remembers... The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Monday, Feb 2, 1874, page 1

- ^ "William Pinkerton Interview". Kansas City Evening Star. July 21, 1881. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ Edwin Daniels

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff Edwin P. Daniels". ODMP remembers... The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ Louis J Lull Find a grave

- ^ Coates, Benjamin (January 2014). "The Pan-American Lobbyist". Diplomatic History. 38 (1): 22–48. doi:10.1093/dh/dht067. JSTOR 26376534. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Rossiter; Brown, John Howard, eds. (1904), "William Eleroy Curtis", The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans, vol. 3, Boston: The Biographical Society

- ^ "Headquarters U.S. Army Corps of Engineers > About > History > Historical Vignettes > General History > 026 - Stolen Payroll". Usace.army.mil. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ "William Harrison Westfall (1843–1881) – Find A Grave Memorial". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

- ^ "Weekly graphic. (Kirksville, Adair Co., Mo.) 1880–1949, July 22, 1881, Image 2". Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. 22 July 1881. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Bell, Bob Boze (13 December 2007). "Little by Liddil (Jesse Goes Down)". True West Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Jesse James is murdered". History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Jesse James shot in the back". History.com. A&E Television Networks, LLC. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ James–Younger Gang: Frank James Trial Archived 2021-05-08 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Trimble, Marshall (1 December 2004). "Did Frank James die in the last shoot-out with the Ford that was still living?". True West Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Walter N. Trenerry (1962,85) Murder in Minnesota, chapter 8: "Highwaymen came riding", Minnesota Historical Society Press

- ^ Peter Braunstein; Michael William Doyle, eds. (July 4, 2013). Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s and 70s. Routledge. ISBN 9781136058905.

- ^ Jesse James and the Movies, Johnny D. Boggs, chapter 3, p.23, pub. McFarland, 6 May 2011, ISBN 9780786484966

- ^ Jesse James and the Movies, Johnny D. Boggs, chapter 3, p.28, pub. McFarland, 6 May 2011, ISBN 9780786484966

- ^ Hansen, Ron (10 October 2006). "Truth, Legend, and Jesse James". Santa Clara Magazine. Santa Clara University. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

Other sources

- B. Wayne Quist (July 2009). "The Murder of Nicholaus Gustafson". The History of the Christdala Evangelical Swedish Lutheran Church of Millersburg, Minnesota (Third ed.). Dundas, Minnesota. pp. 19–23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stiles, T. J. (October 2003). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Vintage. p. 544. ISBN 978-0375705588.

- Settle Jr., William A. (June 1977). Jesse James Was His Name; or, Fact and Fiction concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri. Bison Books. pp. 283. ISBN 978-0803258600.

- Yeatman, Ted P. (February 2003). Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend. Cumberland House; Second Edition. p. 512. ISBN 978-1581823257.

- Brant, Marley (April 1995). The Outlaw Youngers: A Confederate Brotherhood. Madison Books. p. 408. ISBN 978-1568330457.

- Brant, Marley (April 1995). Outlaws: The Illustrated History of the James–Younger Gang. Black Belt Press; First Edition. p. 224. ISBN 978-1880216361.

Further reading

- McLachlan, Sean (2012) The Last Ride of the James–Younger Gang; Jesse James and the Northfield Raid 1876. Osprey Raid Series #35. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849085991

External links

- Northfield Bank Raid in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Website for the American Experience documentary on Jesse James, broadcast on PBS, with transcript and additional material Archived 2011-03-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Website for T. J. Stiles's biography of Jesse James, with excerpts of primary sources and additional essays

- Official website for the family of Frank & Jesse James: Stray Leaves, A James Family in America Since 1650 Archived 2019-02-28 at the Wayback Machine

- John Koblas, author of several Jesse James books

- Yesterday's News blog 1901 newspaper interview with Cole and Jim Younger upon their release from a Minnesota prison

- Northfield (Minnesota) Historical Society Bank Raid Wiki

- Defeat of Jesse James Days, held annually the weekend after Labor Day in Northfield, Minnesota

- The Younger Brothers: After the Attempted Robbery, a podcast by the Minnesota Historical Society on the Younger brothers' time in Stillwater State Prison

- Newspapers report the rise, exploits, and fall of Jesse James and the James–Younger Gang Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Today's James Younger Gang