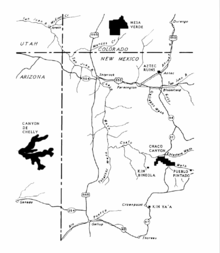

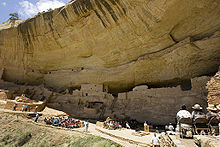

Mesa Verde National Park is an American national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in Montezuma County, Colorado. The park protects some of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloan ancestral sites in the United States.

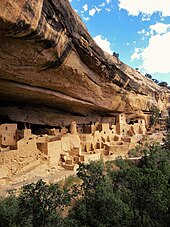

Established by Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, the park occupies 52,485 acres (212 km2) near the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. With more than 5,000 sites, including 600 cliff dwellings,[2] it is the largest archaeological preserve in the United States.[3] Mesa Verde (Spanish for "green table", or more specifically "green table mountain") is best known for structures such as Cliff Palace, one of the largest cliff dwellings in North America.

Starting c. 7500 BC Mesa Verde was seasonally inhabited by a group of nomadic Paleo-Indians known as the Foothills Mountain Complex. The variety of projectile points found in the region indicates they were influenced by surrounding areas, including the Great Basin, the San Juan Basin, and the Rio Grande Valley. Later, Archaic people established semi-permanent rock shelters in and around the mesa. By 1000 BC, the Basketmaker culture emerged from the local Archaic population, and by 750 AD the Ancestral Puebloans had developed from the Basketmaker culture.

The Pueblo people survived using a combination of hunting, gathering, and subsistence farming of crops such as corn, beans, and squash (the "Three Sisters"). They built the mesa's first pueblos sometime after 650, and by the end of the 12th century, they began to construct the massive cliff dwellings for which the park is best known. By 1285, following a period of social and environmental instability driven by a series of severe and prolonged droughts, they migrated south to locations in Arizona and New Mexico, including the Rio Chama, the Albuquerque Basin, the Pajarito Plateau, and the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

Inhabitants

Paleo-Indians

The first occupants of the Mesa Verde region, which spans from southeastern Utah to northwestern New Mexico, were nomadic Paleo-Indians who arrived in the area c. 9500 BC.[4] They followed herds of big game and camped near rivers and streams, many of which dried up as the glaciers that once covered parts of the San Juan Mountains receded. The earliest Paleo-Indians were the Clovis culture and Folsom tradition, defined largely by how they fashioned projectile points. Although they left evidence of their presence throughout the region, there is little indication that they lived in central Mesa Verde during this time.[5]

After 9600 BC, the area's environment grew warmer and drier, a change that brought to central Mesa Verde pine forests and the animals that thrive in them. Paleo-Indians began inhabiting the mesa in increasing numbers c. 7500 BC, though it is unclear whether they were seasonal occupants or year-round residents. Development of the atlatl during this period made it easier for them to hunt smaller game, a crucial advance at a time when most of the region's big game had disappeared from the landscape.[6]

Archaic

6000 BC marks the beginning of the Archaic period in North America. Archaeologists differ as to the origin of the Mesa Verde Archaic population; some believe they developed exclusively from local Paleo-Indians, called the Foothills Mountain Complex, but others suggest that the variety of projectile points found in Mesa Verde indicates influence from surrounding areas, including the Great Basin, the San Juan Basin, and the Rio Grande Valley. The Archaic people probably developed locally, but were also influenced by contact, trade, and intermarriage with immigrants from these outlying areas.[7]

The early Archaic people living near Mesa Verde utilized the atlatl and harvested a wider variety of plants and animals than the Paleo-Indians had while retaining their primarily nomadic lifestyle. They inhabited the outlying areas of the Mesa Verde region, but also the mountains, mesa tops, and canyons, where they created rock shelters and rock art, and left evidence of animal processing and chert knapping. Environmental stability during the period drove population expansion and migration. Major warming and drying from 5000 to 2500 might have led middle Archaic people to seek the cooler climate of Mesa Verde, whose higher elevation brought increased snowpack that, when coupled with spring rains, provided relatively plentiful amounts of water.[7]

By the late Archaic, more people were living in semi-permanent rock shelters that preserved perishable goods such as baskets, sandals, and mats. They started to make a variety of twig figurines that usually resembled sheep or deer. The late Archaic is marked by increased trade in exotic materials such as obsidian and turquoise. Marine shells and abalone from the Pacific coast made their way to Mesa Verde from Arizona, and the Archaic people worked them into necklaces and pendants. Rock art flourished, and people lived in rudimentary houses made of mud and wood. Their early attempts at plant domestication eventually developed into the sustained agriculture that marked the end of the Archaic period, c. 1000.[8]

Basketmaker culture

With the introduction of corn to the Mesa Verde region c. 1000 BC and the trend away from nomadism toward permanent pithouse settlements, the Archaic Puebloan transitioned into what archaeologists call the Basketmaker culture. Basketmaker II people are characterized by their combination of foraging and farming skills, use of the atlatl, and creation of finely woven baskets in the absence of earthen pottery. By 300, corn had become the preeminent staple of the Basketmaker II people's diet, which relied less and less on wild food sources and more on domesticated crops.[9][a]

In addition to the fine basketry for which they were named, Basketmaker II people fashioned a variety of household items from plant and animal materials, including sandals, robes, pouches, mats, and blankets. They also made clay pipes and gaming pieces. Basketmaker men were relatively short and muscular, averaging less than 5.5 feet (1.7 m) tall. Their skeletal remains reveal signs of hard labor and extensive travel, including degenerative joint disease, healed fractures, and moderate anemia associated with iron deficiency. They buried their dead near or amongst their settlements, and often included luxury items as gifts, which might indicate differences in relative social status. Basketmaker II people are also known for their distinctive rock art, which can be found throughout Mesa Verde. They depicted animals and people, in both abstract and realistic forms, in single works and more elaborate panels. A common subject was the hunchbacked flute player that the Hopi call Kokopelli.[11]

By 500 AD, atlatls were being supplanted by the bow and arrow and baskets by pottery, marking the end of the Basketmaker II Era and the beginning of the Basketmaker III Era.[12] Ceramic vessels were a major improvement over pitch-lined baskets, gourds, and animal hide containers, which had been the primary water storage containers in the region. Pottery also protected seeds against mold, insects, and rodents. By 600, Ancestral Pueblo People were using clay pots to cook soups and stews.[13] Year-round settlements first appear around this time. The population of the San Juan Basin increased markedly after 575, when there were very few Basketmaker III sites in Mesa Verde; by the early 7th century, there were many such sites in the mesa. For the next 150 years, villages typically consisted of small groups of one to three residences. The population of Mesa Verde c. 675 was approximately 1,000 to 1,500 people.[14]

Beans and new varieties of corn were introduced to the region c. 700.[15] By 775, some settlements had grown to accommodate more than one hundred people; the construction of large, above-ground storage buildings began around this time. Basketmakers endeavored to store enough food for their family for one year, but also retained residential mobility so they could quickly relocate their dwellings in the event of resource depletion or consistently inadequate crop yields.[14] By the end of the 8th century, the smaller hamlets, which were typically occupied for ten to forty years, had been supplanted by larger ones that saw continuous occupation for as many as two generations.[16] Basketmaker III people established a tradition of holding large ceremonial gatherings near community pit structures.[17]

Ancestral Puebloans

Pueblo I: 750 to 900

750 marks the end of the Basketmaker III Era and the beginning of the Pueblo I period. The transition is characterized by major changes in the design and construction of buildings and the organization of household activities. Pueblo I people doubled their capacity for food storage from one year to two and built interconnected, year-round residences called pueblos. Many household activities that had previously been reserved for subterranean pit-houses were moved to these above-ground dwellings. This altered the function of pit-houses from all-purpose spaces to ones used primarily for community ceremonies, although they continued to house large extended families, particularly during winter months.[18] During the late 8th century, Pueblo people began building square pit structures that archaeologists call protokivas. They were typically 3 or 4 feet (0.91 or 1.22 m) deep and 12 to 20 feet (3.7 to 6.1 m) wide.[19]

The first pueblos appeared at Mesa Verde sometime after 650; by 850 more than half of Pueblo people lived in them. As local populations grew, Puebloans found it difficult to survive on hunting, foraging, and gardening, which made them increasingly reliant on domesticated corn. This shift from semi-nomadism to a "sedentary and communal way of life changed ancestral Pueblo society forever".[20] Within a generation the average number of households in these settlements grew from 1-3 to 15-20, with average populations of two hundred people. Population density increased dramatically, with as many as a dozen families occupying roughly the same space that had formerly housed two. This brought increased security against raids and encouraged greater cooperation amongst residents. It also facilitated trade and intermarriage between clans, and by the late 8th century, as Mesa Verde's population was being augmented by settlers from the south, four distinct cultural groups occupied the same villages.[21]

Large Pueblo I settlements laid claim to the resources found within 15 to 30 square miles (39 to 78 km2). They were typically organized in groups of at least three and spaced about 1 mile (1.6 km) apart. By 860, there were approximately 8,000 people living in Mesa Verde.[22] Within the plazas of larger villages, the Pueblo I people dug massive pit structures of 800 square feet (74 m2) that became central gathering places. These structures represent early architectural expressions of what would eventually develop into the Pueblo II Era great houses of Chaco Canyon. Despite robust growth during the early and mid-9th century, unpredictable rainfall and periodic drought led to a dramatic reversal of settlement trends in the area. Many late Pueblo I villages were abandoned after less than forty years of occupation, and by 880 Mesa Verde's population was in steady decline.[23] The beginning of the 10th century saw widespread depopulation of the region, as people emigrated south of the San Juan River to Chaco Canyon in search of reliable rains for farming.[24] As Pueblo people migrated south, to where many of their ancestors had emigrated two hundred years before, the influence of Chaco Canyon grew, and by 950 Chaco had supplanted Mesa Verde as the region's cultural center.[23]

Pueblo II: 900 to 1150

The Pueblo II Period is marked by the growth and outreach of communities centered around the great houses of Chaco Canyon. Despite their participation in the vast Chacoan system, Puebloan retained a distinct cultural identity while melding regional innovation with ancient tradition, inspiring further architectural advancements; the 9th century Puebloan pueblos influenced two hundred years of Chacoan great house construction.[24] Droughts during the late 9th century rendered Ancestral Pueblo people's dry land farming unreliable, which led to their growing crops only near drainages for the next 150 years. Crop yields returned to healthy levels by the early 11th century.[25] By 1050 the population of the area began to rebound; as agricultural prosperity increased, people immigrated to Mesa Verde from the south. [24]

Pueblonan farmers increasingly relied on masonry reservoirs during the Pueblo II Era. During the 11th century, they built check dams and terraces near drainages and slopes in an effort to conserve soil and runoff. These fields offset the danger of crop failures in the larger dry land fields.[26] By the mid-10th and early 11th centuries, protokivas had evolved into smaller circular structures called kivas, which were usually 12 to 15 feet (3.7 to 4.6 m) across. These Mesa Verde-style kivas included a feature from earlier times called a sipapu, which is a hole dug in the north of the chamber and symbolizes the Ancestral Puebloan's place of emergence from the underworld.[19] At this time, Ancestral Pueblo people began to move away from the post and mud jacal-style buildings that marked the Pueblo I Period toward masonry construction, which had been utilized in the region as early as 700, but was not widespread until the 11th and 12th centuries.[27]

The expansion of Chacoan influence in the Mesa Verde area left its most visible mark in the form of Chaco-style masonry great houses that became the focal point of many Puebloan villages after 1075.[24] Far View House, the largest of these, is considered a classic Chaco "outlier," on which construction likely began between 1075 and 1125, although some archaeologists argue that it was begun as early as 1020.[28] The era's timber and earth unit pueblos were typically inhabited for about twenty years.[29] During the early 12th century, the locus of regional control shifted away from Chaco to Aztec, New Mexico, in the southern Mesa Verde region.[24][b] By 1150, drought had once again stressed the region's inhabitants, leading to a temporary cessation of great house construction at Mesa Verde.[31]

Pueblo III: 1150 to 1300

A severe drought from 1130 to 1180 led to rapid depopulation in many parts of the San Juan Basin, particularly at Chaco Canyon. As the extensive Chacoan system collapsed, people increasingly migrated to Mesa Verde, causing major population growth in the area. This led to much larger settlements of six to eight hundred people, which reduced mobility for Puebloan, who had in the past frequently relocated their dwellings and fields as part of their agriculture strategy. In order to sustain these larger populations, they dedicated more and more of their labor to farming. Population increases also led to expanded tree felling that reduced habitat for many wild plant and animal species that the Puebloan had relied on, further deepening their dependency on domesticated crops that were susceptible to drought-related failure.[33] A recent study has shown that residents resorted to cannibalism starting in 1150 due to the discovery of disarticulated human remains that were prepared and consumed.[34]

The Chacoan system brought large quantities of imported goods to Mesa Verde during the late 11th and early 12th centuries, including pottery, shells, and turquoise, but by the late 12th century, as the system collapsed, the amount of goods imported by the mesa quickly declined, and Mesa Verde became isolated from the surrounding region.[35] For approximately six hundred years, most Puebloan farmers had lived in small, mesa-top homesteads of one or two families. They were typically located near their fields and walking distance to sources of water. This practice continued into the mid- to late 12th century, but by the start of the 13th century they began living in canyon locations that were close to water sources and within walking distance of their fields.[36]

Ancestral Pueblo villages thrived during the mid-Pueblo III Era, when architects constructed massive, multi-story buildings, and artisans adorned pottery with increasingly elaborate designs. Structures built during this period have been described as "among the world's greatest archaeological treasures".[37] Pueblo III masonry buildings were typically occupied for approximately fifty years, more than double the usable lifespan of the Pueblo II jacal structures. Others were continuously inhabited for two hundred years or more. Architectural innovations such as towers and multi-walled structures also appear during the Pueblo III Era. Mesa Verde's population remained fairly stable during the 12th century drought.[38] At the start of the 13th century, approximately 22,000 people lived there.[39] The area saw moderate population increases during the following decades, and dramatic ones from 1225 to 1260.[30] Most of the people in the region lived in the plains west of the mesa at locations such as Yellow Jacket Pueblo, near Cortez, Colorado.[40] Others colonized canyon rims and slopes in multi-family structures that grew to unprecedented size as populations swelled.[41] By 1260, the majority of Puebloans lived in large pueblos that housed several families and more than one hundred people.[36]

The 13th century saw 69 years of below average rainfall in the Mesa Verde region, and after 1270 the area suffered from especially cold temperatures. Dendrochronology indicates that the last tree felled for construction on the mesa was cut in 1281.[42] There was a major decline in ceramic imports to the region during this time, but local production remained steady.[43] Despite challenging conditions, the Puebloans continued to farm the area until a severely dry period from 1276 to 1299 ended seven hundred years of continuous human occupation at Mesa Verde.[25] Archaeologists refer to this period as the "Great Drought".[44] The last inhabitants of the mesa left the area c. 1285.[45]

Warfare

During the Pueblo III period (1150 to 1300), Puebloans built numerous stone masonry towers that likely served as defensive structures. They often incorporated hidden tunnels connecting the towers to associated kivas.[46] Warfare was conducted using the same tools the Puebloans used for hunting game, including bows and arrows, stone axes, and wooden clubs and spears. They also crafted hide and basket shields that were used only during battles.[47] Periodic warfare occurred on the mesa throughout the 13th century.[30] Civic leaders in the region likely attained power and prestige by distributing food during times of drought. This system probably broke down during the "Great Drought", leading to intense warfare between competing clans.[48] Increasing economic and social uncertainty during the century's final decades led to widespread conflict. Evidence of partly burned villages and post-mortem trauma have been uncovered, and the residents of one village appear to have been the victims of a site-wide massacre.[49]

Evidence of violence and cannibalism has been documented in the central Mesa Verde region.[50][c] While most of the violence, which peaked between 1275 and 1285, is generally ascribed to in-fighting amongst Puebloans, archaeological evidence found at Sand Canyon Pueblo, in Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, suggests that violent interactions also occurred between Puebloans and people from outside the region.[30] Evidence of the attacks was discovered by members of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center during the 1990s. The assaults, which also occurred at the national monument's Castle Rock Pueblo, were dated to c. 1280, and are considered to have effectively ended several centuries of Puebloan occupation at those sites.[51] Many of the victims showed signs of skull fractures, and the uniformity of the injuries suggest that most were inflicted with a small stone axe. Others were scalped, dismembered, and cannibalized. The anthropophagy (cannibalism) might have been undertaken as a survival strategy during times of starvation.[52] The archaeological record indicates that, rather than being isolated to the Mesa Verde region, violent conflict was widespread in North America during the late 13th and early 14th centuries, and was likely exacerbated by global climate changes that negatively affected food supplies throughout the continent.[53]

Migration

The Mesa Verde region saw unusually cold and dry conditions during the beginning of the 13th century. This might have driven emigration to Mesa Verde from less hospitable locations. The added population stressed the mesa's environment, further straining an agricultural society that was suffering from drought.[54] The region's bimodal precipitation pattern, which brought rainfall during spring and summer and snowfall during autumn and winter, began to fail post-1250.[44] After 1260, there was a rapid depopulation of Mesa Verde, as "tens of thousands of people" emigrated or died from starvation.[30] Many smaller communities in the Four Corners region were also abandoned during this period.[55][56] The Ancestral Puebloans had a long history of migration in the face of environmental instability, but the depopulation of Mesa Verde at the end of the 13th century was different in that the region was almost completely emptied, and no descendants returned to build permanent settlements.[57] While drought, resource depletion, and overpopulation all contributed to instability during the last two centuries of Ancestral Puebloan occupation, their overdependence on maize crops is considered the "fatal flaw" of their subsistence strategy.[58][d]

The vacating Ancestral Pueblo people left almost no direct evidence of their migration, but they left behind household goods, including cooking utensils, tools, and clothing, which gave archaeologists the impression that the emigration was haphazard or hurried. An estimated 20,000 people lived in the region during the 13th century, but by the start of the 14th century the area was nearly uninhabited.[61][e] Many surviving emigrants may have relocated to southern Arizona and New Mexico.[62] Although the rate of settlement is unclear, increases in sparsely populated areas, such as Rio Chama, Pajarito Plateau, and Santa Fe, correspond directly with the period of migration from Mesa Verde. Archaeologists believe the Puebloans who settled in the areas near the Rio Grande, where Mesa Verde black-on-white pottery became widespread during the 14th century, were likely related to the households they joined and not unwelcome intruders. Archaeologists view this migration as a continuation, versus a dissolution, of Ancestral Puebloan society and culture.[63] Many others relocated to the banks of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona.[64] While archaeologists tend to focus on the "push" factors that drove the Puebloans away from the region, there were also several environmental "pull factors", such as warmer temperatures, better farming conditions, plentiful timber, and bison herds, which incentivized relocation to the area near the Rio Grande.[65] In addition to numerous settlements along the Rio Grande, contemporary descendants of the Puebloans live in pueblos at Acoma, Zuni, Jemez, and Laguna.[60][f]

Organization

Although Chaco Canyon might have exerted regional control over Mesa Verde during the late 11th and early 12th centuries, most archaeologists view the Mesa Verde region as a collection of smaller communities based on central sites and related outliers that were never fully integrated into a larger civic structure.[67] Several ancient roads, averaging 15 to 45 feet (4.6 to 13.7 m) wide and lined with earthen berms, have been identified in the region. Most appear to connect communities and shrines; others encircle great house sites. The extent of the network is unclear, but no roads have been discovered leading to the Chacoan Great North Road, or directly connecting Mesa Verde and Chacoan sites.[68]

Ancestral Puebloan shrines, called herraduras, have been identified near road segments in the region. Their purpose is unclear, but several C-shaped herraduras have been excavated, and they are thought to have been "directional shrines" used to indicate the location of great houses.[69][g]

Architecture

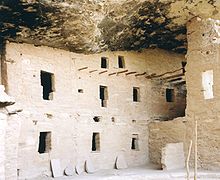

Mesa Verde is best known for a large number of well-preserved cliff dwellings, houses built in alcoves, or rock overhangs along the canyon walls. The structures contained within these alcoves were mostly blocks of hard sandstone, held together and plastered with adobe mortar. Specific constructions had many similarities but were generally unique in form due to the individual topography of different alcoves along the canyon walls. In marked contrast to earlier constructions and villages on top of the mesas, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde reflected a region-wide trend towards the aggregation of growing regional populations into close, highly defensible quarters during the 13th century.[70]

Pueblo buildings were built with stone, windows facing south, and in U, E and L shapes. The buildings were located more closely together and reflected deepening religious celebration. Towers were built near kivas and likely used for lookouts. Pottery became more versatile, including pitchers, ladles, bowls, jars and dishware for food and drink. White pottery with black designs emerged, the pigments coming from plants. Water management and conservation techniques, including the use of reservoirs and silt-retaining dams, also emerged during this period.[71] Styles for these sandstone/mortar constructions, both surface and cliff dwellings, included T-shaped windows and doors. This has been taken by some archaeologists, including Stephen H. Lekson, as evidence of the continuing reach of the Chacoan system.[72] Other researchers see these elements as part of a more generalized Puebloan style or spiritual significance rather than evidence of a continuing specific elite socioeconomic system.[73]

While much of the construction in these sites is consistent with common Pueblo architectural forms, including kivas, towers, and pit-houses, the space constrictions of these alcoves necessitated what seems to have been a far denser concentration of their populations. Mug House, a typical cliff dwelling of the period, was home to around 100 people who shared 94 small rooms and eight kivas built against each other and sharing many of their walls; builders in these areas maximized space in any way they could, with no areas considered off-limits to construction.[41]

Astronomy

The Pueblo people used astronomical observations to plan their farming and religious ceremonies, drawing on both natural features in the landscape and masonry structures built for this purpose. Several great houses in the region were aligned to the cardinal directions, which positioned windows, doors, and walls along the path of the sun, whose rays would indicate the passing of seasons. Mesa Verde's Sun Temple is thought to have been an astronomical observatory.[74]

The temple is D-shaped, and its alignment is 10.7 degrees off true east–west.[75] Its location and orientation indicate that its builders understood the cycles of both the sun and the moon.[76] It is aligned to the major lunar standstill, which occurs once every 18.6 years, and the sunset during the winter solstice, which can be viewed setting over the temple from a platform at the south end of Cliff Palace, across Fewkes Canyon. At the bottom of the canyon is the Sun Temple fire pit, which is illuminated by the first rays of the rising sun during the winter solstice. Sun Temple is one of the largest exclusively ceremonial structures ever built by the Ancestral Puebloans.[77][h]

Agriculture and water-control systems

Starting in the 6th century, the farmers living in central Mesa Verde cultivated corn, beans, squash, and gourds. The combination of corn and beans provided the Puebloans with the amino acids of a complete protein. When conditions were good, 3 or 4 acres (12,000 or 16,000 m2) of land would provide enough food for a family of three or four individuals for one year, providing they supplemented with game and wild plants. As Puebloans increasingly relied on corn as a dietary staple, the success or failure of crop yields factored heavily into their lives. The mesa tilts slightly to the south, which increased its exposure to the sun.[79] Before the introduction of pottery, foods were baked, roasted, and parched. Hot rocks dropped into containers could bring water to a brief boil, but because beans must be boiled for an hour or more their use was not widespread until after pottery had disseminated throughout the region. With the increased availability of ceramics after 600, beans became much easier to cook. This provided a high quality protein that reduced reliance on hunting. It also aided corn cultivation, as legumes add much needed nutrients to soils they are grown in, which likely increased corn yields.[80]

Most Pueblo people practiced dry farming, which relied on rain to water their crops, but others utilized runoff, springs, seeps, and natural collection pools. Starting in the 9th century, they dug and maintained reservoirs that caught runoff from summer showers and spring snowmelt; some crops were watered by hand.[81] Archaeologists believe that prior to the 13th century, springs and other sources of water were considered shared public resources, but as the Pueblo moved into increasingly larger pueblos built near or around water supplies control was privatized and limited to members of the surrounding community.[82]

Between 750 and 800, Puebloans began constructing two large water containment structures in canyon bottoms – the Morefield and Box Elder reservoirs. Soon afterward, work began on two more: the Far View and Sagebrush reservoirs, which were approximately 90 feet (30 m) across and constructed on the mesa top. The reservoirs lie on an east–west line that runs for approximately 6 miles (10 km), which suggests builders followed a centralized plan for the system. In 2004, the American Society of Civil Engineers designated these four structures as National Civil Engineering Historic Landmarks.[83] A 2014 geospatial analyses suggested that neither collection nor retention of water was possible in the Far View Reservoir. This interpretation views the structure as a ceremonial space with procession roads in an adaptation of Chacoan culture.[84]

Hunting and foraging

Puebloans typically harvested local small game, but sometimes organized hunting parties that traveled long distances. Their main sources of animal protein came from mule deer and rabbits, but they occasionally hunted Bighorn sheep, antelope, and elk.[85] They began to domesticate turkeys starting around 1000, and by the 13th century consumption of the animal peaked, supplanting deer as the primary protein source at many sites. These domesticated turkeys consumed large amounts of corn, which further deepened reliance on the staple crop.[86] Puebloans wove blankets from turkey feathers and rabbit fur, and made implements such as awls and needles from turkey and deer bones. Despite the availability of fish in the area's rivers and streams, archaeological evidence suggests that they were rarely eaten.[85]

Puebloans supplemented their diet by gathering the seeds and fruits of wild plants, searching large expanses of land while procuring these resources. Depending on the season, they collected piñon nuts and juniper berries, weedy goosefoot, pigweed, purslane, tomatillo, tansy mustard, globe mallow, sunflower seeds, and yucca, as well as various species of grass and cacti. Prickly pear fruits provided a rare source of natural sugar. Wild seeds were cooked and ground up into porridge. They used sagebrush and mountain mahogany, along with piñon and juniper, for firewood. They also smoked wild tobacco.[87] Because the Ancestral Puebloans considered all material consumed and discarded by their communities as sacred, their midden piles were viewed with reverence. Starting during the Basketmaker III period, c. 700, Puebloans often buried their dead in these mounds.[74]

Pottery

Scholars are divided as to whether pottery was invented in the Four Corners region or introduced from the south. Specimens of shallow, unfired clay bowls found at Canyon de Chelly indicate the innovation might have been derived from using clay bowls to parch seeds. Repeated uses rendered these bowls hard and impervious to water, which might represent the first fired pottery in the region. An alternate theory suggests that pottery originated in the Mogollon Rim area to the south, where brown-paste bowls were used during the first few centuries of the common era.[88] Others believe pottery was introduced to Mesa Verde from Mexico, c. 300 CE.[89] There is no evidence of ancient pottery markets in the region, but archaeologists believe that local potters exchanged decorative wares between families. Cooking pots made with crushed igneous rock tempers from places like Ute Mountain were more resilient and desirable, and Puebloans from throughout the region traded for them.[90]

Neutron activation analysis indicates that much of the black-on-white pottery found at Mesa Verde was produced locally. Cretaceous clays from both the Dakota and Menefee Formations were used in black-on-white wares, and Mancos Formation clays for corrugated jars.[91][i] Evidence that pottery of both types moved between several locations around the region suggests interaction between groups of ancient potters, or they might have shared a common source of raw materials.[91] The Mesa Verde black-on-white pottery was produced at three locations: Sand Canyon, Castle Rock, and Mesa Verde.[92] Archeological evidence indicates that nearly every household had at least one member who worked as a potter. Trench kilns were constructed away from pueblos and closer to sources of firewood. Their sizes vary, but the larger ones were up to 24 feet (7.3 m) long and thought to have been shared kilns that served several families. Designs were added to ceramic vessels with a Yucca-leaf brush and paints made from iron, manganese, beeplant, and tansy mustard.[93]

Most of the pottery found in 9th century pueblos was sized for individuals or small families, but as communal ceremonialism expanded during the 13th century, many larger, feast–sized vessels were produced.[94] Corrugated decorations appear on Mesa Verde grey wares after 700, and by 1000 entire vessels were crafted in this way. The technique created a rough exterior surface that was easier to hold on to than regular gray wares, which were smooth.[95] By the 11th century these corrugated vessels, which dissipated heat more efficiently than smoother ones, had largely replaced the older style, whose tendency to retain heat made them prone to boiling over.[96] Corrugation likely developed as ancient potters attempted to mimic the visual properties of coiled basketry.[97] Corrugated wares were made using clay from formations other than Menefee, which suggests that ancient potters selected different clays for different styles.[92] Potters also selected clays and altered firing conditions to achieve specific colors. Under normal conditions, pots made of Mancos shale turned grey when fired, and those made of Morrison Formation clay turned white. Clays from southeastern Utah turned red when fired in a high-oxygen environment.[96]

Rock art and murals

Rock art is found throughout the Mesa Verde region, but its dispersion is uneven and periodic. Some locations have numerous examples; others have none, and some periods saw prolific creation, while others saw little. Styles also vary over time. Examples are relatively rare on Mesa Verde proper, but abundant in the middle San Juan River area, which might indicate the river's importance as a travel route and key source of water. Common motifs in the rock art of the region include anthropomorphic figures in procession and during copulation or childbirth, handprints, animal and people tracks, wavy lines, spirals, concentric circles, animals, and hunting scenes.[99] As the region's population plummeted during the late 13th century, the subject of Pueblonian rock art increasingly shifted to depictions of shields, warriors, and battle scenes.[100] Modern Hopi have interpreted the petroglyphs at Mesa Verde's Petroglyph Point as depictions of various clans of people.[98]

Starting during the late Pueblo II period (1020) and continuing through Pueblo III (1300), the Ancestral Puebloans of the Mesa Verde region created plaster murals in their great houses, particularly in their kivas. The murals contained both painted and inscribed images depicting animals, people, and designs used in textiles and pottery dating back as far as Basketmaker III, c. 500. Others depict triangles and mounds thought to represent mountains and hills in the surrounding landscape. The murals were typically located on the face of the kiva bench and usually encircled the room. Geometric patterns that resemble symbols used in pottery and zigzag that represent stitches used in basket making are common motifs. The painted murals include the colors red, green, yellow, white, brown, and blue. The designs were still in use by the Hopi during the 15th and 16th centuries.[101]

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Mesa Verde National Park has a dry-summer humid continental climate (Dsa). According to the United States Department of Agriculture, the Plant Hardiness zone at Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters at 6952 ft (2119 m) elevation is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of −0.1 °F (−17.8 °C).[102]

The region's precipitation pattern is bimodal, meaning agriculture is sustained through snowfall during winter and autumn and rainfall during spring and summer.[44] Water for farming and consumption was provided by summer rains, winter snowfall, and seeps and springs in and near the Mesa Verde villages. At 7,000 feet (2,100 m), the middle mesa areas were typically ten degrees Fahrenheit (5 °C) cooler than the mesa top, which reduced the amount of water needed for farming.[103] The cliff dwellings were built to take advantage of solar energy. The angle of the sun in winter warmed the masonry of the cliff dwellings, warm breezes blew from the valley, and the air was 10 to 20°F (5-10°C) warmer in the canyon alcoves than on the top of the mesa. In the summer, with the sun high overhead, much of the village was protected from direct sunlight in the high cliff dwellings.[104]

| Climate data for Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1922–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

68 (20) |

73 (23) |

84 (29) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

65 (18) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 51.5 (10.8) |

54.6 (12.6) |

65.0 (18.3) |

73.1 (22.8) |

82.2 (27.9) |

90.3 (32.4) |

94.0 (34.4) |

90.5 (32.5) |

86.1 (30.1) |

76.6 (24.8) |

64.3 (17.9) |

53.8 (12.1) |

94.3 (34.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.6 (4.2) |

42.7 (5.9) |

51.2 (10.7) |

59.3 (15.2) |

69.2 (20.7) |

81.3 (27.4) |

86.4 (30.2) |

83.5 (28.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

63.3 (17.4) |

50.4 (10.2) |

39.9 (4.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

33.0 (0.6) |

40.4 (4.7) |

46.8 (8.2) |

55.9 (13.3) |

66.8 (19.3) |

72.5 (22.5) |

70.3 (21.3) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

39.6 (4.2) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

49.9 (10.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.0 (−6.7) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

34.4 (1.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

52.3 (11.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

57.0 (13.9) |

50.0 (10.0) |

38.6 (3.7) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

38.0 (3.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 4.3 (−15.4) |

6.8 (−14.0) |

15.0 (−9.4) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

38.8 (3.8) |

49.9 (9.9) |

48.7 (9.3) |

36.5 (2.5) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

11.5 (−11.4) |

4.4 (−15.3) |

0.2 (−17.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −20 (−29) |

−15 (−26) |

2 (−17) |

4 (−16) |

11 (−12) |

27 (−3) |

38 (3) |

38 (3) |

26 (−3) |

5 (−15) |

−3 (−19) |

−15 (−26) |

−20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.96 (50) |

1.66 (42) |

1.38 (35) |

1.14 (29) |

1.13 (29) |

0.47 (12) |

1.41 (36) |

2.05 (52) |

1.77 (45) |

1.44 (37) |

1.19 (30) |

1.51 (38) |

17.11 (435) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 18.1 (46) |

12.0 (30) |

8.0 (20) |

5.0 (13) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.5 (3.8) |

5.6 (14) |

14.2 (36) |

65.0 (165) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 13.2 (34) |

13.8 (35) |

8.9 (23) |

2.5 (6.4) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

3.9 (9.9) |

7.4 (19) |

17.4 (44) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.4 | 8.1 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 7.5 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 7.6 | 84.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.3 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 28.6 |

| Source: NOAA[105][106] | |||||||||||||

Anthropogenic ecology and geography

Anthropogenic ecology refers to the human impact on animals and plants in an ecosystem.[85] A shift from medium and large game animals, such as deer, bighorn sheep, and antelope, to smaller ones like rabbits and turkey during the mid-10th to mid-13th centuries might indicate that Pueblonian subsistence hunting had dramatically altered faunal populations on the mesa.[107] Analysis of pack rat midden indicates that, with the exception of invasive species such as tumbleweed and clover, the flora and fauna in the area have remained relatively consistent for the past 4,000 years.[108]

According to the A. W. Kuchler U.S. Potential natural vegetation Types, Mesa Verde National Park has a Juniper/Pinyon (23) potential vegetation type with a Great Basin montane forest /Southwest Forest (4) potential vegetation form.[109]

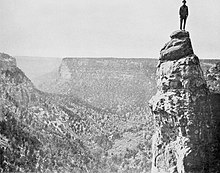

Mesa Verde's canyons were created by streams that eroded the hard sandstone that covers the area. This resulted in Mesa Verde National Park elevations ranging from about 6,000 to 8,572 feet (1,829 to 2,613 m), the highest elevation at Park Point. The terrain in the park is now a transition zone between the low desert plateaus and the Rocky Mountains.[71]

Geology

Although the area's first Spanish explorers named the feature Mesa Verde, the term is a misnomer, as true mesas are almost perfectly flat. Because Mesa Verde is slanted to the south, the proper geological term is cuesta, not mesa. The park is made up of several smaller cuestas located between canyons. Mesa Verde's slant contributed to the formation of the alcoves that have preserved the area's cliff dwellings.[110]

In the late Cretaceous Period, the Mancos Shale was deposited on top of the Dakota Sandstone, which is the rock formation that can be found under much of Colorado. The beds of the Mancos Shale are "fine-grained sand-stones, mudstones, and shales" which accumulated in the deep water of the Cretaceous Sea. It has a high clay content which causes it to expand when wet leading to sliding of the terrain. On top of this shale, there are three formations in the Mesaverde group which reflect the changes in depositional environment in the area over time. The first is the Point Lookout Sandstone, which is named for the Point Lookout feature in the park (elevation 8,427 ft (2,569 m)). This sandstone, which formed in the marine environment of shallow water when the Cretaceous sea was receding, is "massive, fine-grained, cross-bedded, and very resistant", in its layers reflecting waves and currents that were present during the time of its formation. Its sediments are approximately 400 feet (100 m) thick, and its upper layers feature fossiliferous invertebrates.[111]

Next is the Menefee Formation, the middle formation whose content features interbedded carbonaceous shales, siltstones, and sandstones. These were deposited in semi-marine environments of brackish water, such as swamps and lagoons. Due to its depositional environment and the organic material in its composition, there are thin coal seams running through the Menefee Formation. At the top, this formation is intruded upon by the Cliff House Sandstone.[111]

The Cliff House Sandstone is the area's youngest rock layer. It was formed after the Cretaceous sea had completely receded and as a result has a high sand content from beaches, dunes, etc. and from this receives its characteristic yellow tint to its canyon faces. Like the Point Lookout Sandstone, it is about 400 feet (100 m) thick. It contains numerous fossil beds of different types of shells, fish teeth, and other invertebrate leftovers from the receded sea. The shale zones in this feature determine where alcoves formed where the Ancestral Puebloans constructed their dwellings.[111]

Continuing through the Cretaceous period and into the early Tertiary, there was uplifting in the area of the Colorado Plateau, the San Juan Mountains, and the La Plata Mountains, which led to the formation of the Mesa Verde pediment with the help of erosion. Small channels of water ran across this formation depositing gravel. Later in the tertiary, the last period of uplift and rock tilting towards the south caused these streams to cut rapidly into the rock removing loose sediment and forming the vast canyons seen today. This caused the isolation of the Mesa Verde pediment from surrounding rock. Today, since the climate is more arid, these erosional processes are slowed.[111]

Rediscovery

Mexican-Spanish missionaries and explorers Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, seeking a route from Santa Fe to California, faithfully recorded their travels in 1776. They reached Mesa Verde (green plateau) region, which they named after its high, tree-covered plateaus, but they never got close enough, or into the needed angle, to see the ancient stone villages.[112][113] They were the first Europeans to travel the route through much of the Colorado Plateau into Utah and back through Arizona to New Mexico.[114]

The Mesa Verde region has long been occupied by the Utes, and an 1868 treaty between them and the United States government recognized Ute ownership of all Colorado land west of the Continental Divide. After there had become an interest in land in western Colorado, a new treaty in 1873 left the Ute with a strip of land in southwestern Colorado between the border with New Mexico and 15 miles north. Most of Mesa Verde lies within this strip of land. The Ute wintered found sanctuary there and the high plateaus of Mesa Verde. Believing the cliff dwellings to be sacred ancestral sites, they did not live in the ancient dwellings.[112]

Occasional trappers and prospectors visited, with one prospector, John Moss, making his observations known in 1873.[115] The following year, Moss led eminent photographer William Henry Jackson through Mancos Canyon, at the base of Mesa Verde. There, Jackson both photographed and publicized a typical stone cliff dwelling.[115] Geologist William H. Holmes retraced Jackson's route in 1875.[115] Reports by both Jackson and Holmes were included in the 1876 report of the Hayden Survey, one of the four federally financed efforts to explore the American West. These and other publications led to proposals to systematically study Southwestern archaeological sites.[115]

In her quest to find Ancestral Puebloan settlements, Virginia McClurg, a journalist for the New York Daily Graphic, visited Mesa Verde in 1882 and 1885. Her party rediscovered Echo Cliff House, Three Tier House, and Balcony House in 1885; these trips inspired her to protect the dwellings and artifacts.[71][116]

Wetherills

A family of cattle ranchers, the Wetherills, befriended members of the Ute tribe near their ranch southwest of Mancos, Colorado. With the Ute tribe's approval, the Wetherills were allowed to bring cattle into the lower, warmer plateaus of the present Ute reservation during winter. Word of the Ancestral Puebloan great houses had spread, and Acowitz, a member of the Ute tribe, told the Wetherills of a special cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde: "Deep in that canyon and near its head are many houses of the old people – the Ancient Ones. One of those houses, high, high in the rocks, is bigger than all the others. Utes never go there, it is a sacred place."[117][118]

On December 18, 1888, Richard Wetherill and cowboy Charlie Mason rediscovered Cliff Palace after spotting the ruins from the top of Mesa Verde. Wetherill gave the ruin its present-day name. Richard Wetherill, family and friends explored the ruins and gathered artifacts, some of which they sold to the Historical Society of Colorado and much of which they kept.[119][118] Among the people who stayed with the Wetherills and explored the cliff dwellings was mountaineer, photographer, and author Frederick H. Chapin, who visited the region during 1889 and 1890. He described the landscape and ruins in an 1890 article and later in an 1892 book, The Land of the Cliff-Dwellers, which he illustrated with hand-drawn maps and personal photographs.[116]

Gustaf Nordenskiöld

The Wetherills also hosted Gustaf Nordenskiöld, the son of polar explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, in 1891.[120][121] Nordenskiöld was a trained mineralogist who introduced scientific methods to artifact collection, recorded locations, photographed extensively, diagrammed sites, and correlated what he observed with existing archaeological literature as well as the home-grown expertise of the Wetherills.[122] He removed many artifacts and sent them to Sweden, where they eventually went to the National Museum of Finland. Nordenskiöld published, in 1893, The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde.[123] When Nordenskiöld shipped the collection that he made of Mesa Verde artifacts, the event initiated concerns about the need to protect Mesa Verde land and its resources.[124]

National park

In 1889, Goodman Point Pueblo became the first pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Mesa Verde region to gain federal protection. It was the first such site to be protected in the US.[37] Virginia McClurg was diligent in her efforts between 1887 and 1906 to inform the United States and European community of the importance of protecting the important historical material and dwellings in Mesa Verde.[125] Her efforts included enlisting support from 250,000 women through the Federation of Women's Clubs, writing and having published poems in popular magazines, giving speeches domestically and internationally, and forming the Colorado Cliff Dwellers Association.

The Colorado Cliff Dwellers' purpose was to protect the resources of Colorado cliff dwellings, reclaiming as much of the original artifacts as possible and sharing information about the people who dwelt there. A fellow activist for protection of Mesa Verde and prehistoric archaeological sites included Lucy Peabody, who, located in Washington, D.C., met with members of Congress to further the cause.[122][126][116] Former Mesa Verde National Park superintendent Robert Heyder communicated his belief that the park might have been far more significant with the hundreds of artifacts taken by Nordenskiöld.[127]

By the end of the 19th century, it was clear that Mesa Verde needed protection from people in general who came to Mesa Verde and created or sold their own collection of artifacts. In a report to the Secretary of the Interior, Smithsonian Institution Ethnologist Jesse Walter Fewkes described vandalism at Mesa Verde's Cliff Palace:

Parties of "curio seekers" camped on the ruin for several winters, and it is reported that many hundred specimens there have been carried down the mesa and sold to private individuals. Some of these objects are now in museums, but many are forever lost to science. In order to secure this valuable archaeological material, walls were broken down ... often simply to let light into the darker rooms; floors were invariably opened and buried kivas mutilated. To facilitate this work and get rid of the dust, great openings were broken through the five walls which form the front of the ruin. Beams were used for firewood to so great an extent that not a single roof now remains. This work of destruction, added to that resulting from erosion due to rain, left Cliff Palace in a sad condition.[128]

Many artifacts from Mesa Verde are now located in museums and private collections in the US and across the world. A representative selection of pottery vessels and other objects, for example, is now in the British Museum in London.[129] In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt approved creation of the Mesa Verde National Park and the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906.[130] The park was an effort to "preserve the works of man" and was the first park created to protect a location of cultural significance.[125] The park was named with the Spanish term for green table because of its forests of juniper and piñon trees.[131]

In 1976, 8,500 acres (3,440 ha) was designated a wilderness area. These three small and separate sections of the National Park are located on the steep north and east boundaries and serve as buffers to further protect the significant Native American sites. Unlike most wilderness areas, visitor access to Mesa Verde Wilderness is prohibited, along with the rest of the park's backcountry.[132][133]

Excavation and protection

Between 1908 and 1922, Spruce Tree House, Cliff Palace, and Sun Temple ruins were stabilised.[134] Most of the early efforts were led by Jesse Walter Fewkes.[135] During the 1930s and 40s, Civilian Conservation Corps workers, starting in 1932, played key roles in excavation efforts, building trails and roads, creating museum exhibits and constructing buildings at Mesa Verde.[135] From 1958 to 1965, Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project included archaeological excavations, stabilization of sites, and surveys. With excavation and study of eleven Wetherill Mesa sites, it is considered the largest archaeological effort in the US.[135] The project oversaw the excavation of Long House and Mug House.[136]

In 1966, as with all historical areas administered by the National Park Service, Mesa Verde was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1987, the Mesa Verde Administrative District was listed on the register.[137] It was designated a World Heritage Site in 1978.[135] In its 2015 travel awards, Sunset magazine named Mesa Verde National Park "the best cultural attraction" in the Western United States.[138]

Conflicts with local tribes

Clashes between non-Indigenous environmentalists and local tribes surrounding the ruins at Mesa Verde began even before the park's official establishment. Conflicts over who laid claim to the land surrounding the ruins came to fruition in 1911, when the US government wanted to secure more land for the park that was owned by the Ute Indians. The Utes were reluctant to agree to the land swap proposed by the government, noting that the land they were seeking was the best land the tribe owned. Frederick Abbott, working with Indian Office official James McLaughlin, proclaimed to be an ally to the Ute in negotiations. Abbott later claimed that the "government was stronger than the Utes," saying that when the government finds "old ruins on land that it wants to take for public purposes, it has the right to take it ..." Feeling they were left with no other options, the Utes reluctantly agreed to trade the 10,000 acres (40 km2) on Chapin Mesa for 19,500 acres (79 km2) on Ute Mountain.

The Utes continued to battle the Bureau of Indian Affairs to prevent more Ute land from being incorporated into the park. In 1935, the BIA attempted to gain back some the land traded in 1911. Additionally, superintendent Jesse L. Nusbaum later confessed that the Ute Mountain land traded for Chapin Mesa in 1911 belonged to the tribe anyway, meaning the government had traded land that never belonged to them in the first place.[139]

Other issues unrelated to land disputes emerged as a result of park activities. In the 1920s, the park began offering "Indian ceremony" performances that gained popularity among visiting tourists; however, the ceremonies did not actually reflect the rites of the Ancient Puebloans who lived in the cliff dwellings nor the rites of the modern Ute. Navajo day laborers performed these rituals, resulting in "the wrong Indians doing the wrong dance on ... the wrong land." In addition to the inaccuracy of the ceremonies, a question of whether Navajo dancers were paid fairly also resulted in questions regarding the lack of local American Indians being employed in other capacities in the park. Additionally, the park offered little financial benefits to the Ute Mountain Ute despite their land swap making much of the park possible.[140]

Services

The entrance to Mesa Verde National Park is on U.S. Route 160, approximately 9 miles (14 km) east of the community of Cortez and 7 miles (11 km) west of Mancos, Colorado.[141] The park covers 52,485 acres (21,240 ha)[142] It contains 4,372 documented sites, including more than 600 cliff dwellings.[143] It is the largest archaeological preserve in the US.[3][144] It protects some of the most important and best-preserved archaeological sites in the country.[131] The park initiated the Archaeological Site Conservation Program in 1995. It analyses data pertaining to how sites are constructed and utilized.[136]

The Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center is located just off of Highway 160 and is before the park entrance booths. The Visitor and Research Center opened in December 2012. Chapin Mesa (the most popular area) is 20 miles (32 km) beyond the visitor center.[141] Mesa Verde National Park is an area of federal exclusive jurisdiction. Because of this all law enforcement, emergency medical service, and wildland/structural fire duties are conducted by federal National Park Service Law Enforcement Rangers. The Mesa Verde National Park Post Office has the ZIP code 81330.[145] Access to park facilities vary by season. Three of the cliff dwellings on Chapin Mesa are open to the public. The Chapin Mesa Museum is open all year. Spruce Tree House is closed due to rock fall danger. Balcony House, Long House and Cliff Palace require tour tickets for ranger-guided tours. Many other dwellings are visible from the road but not open to tourists. The park offers hiking trails, a campground, and, during peak season, facilities for food, fuel, and lodging; these are unavailable in the winter.[141]

The park's early administrative buildings, located on Chapin Mesa, form an architecturally significant complex of buildings. Built in the 1920s, the Mesa Verde administrative complex was one of the first examples of the Park Service using culturally appropriate design in the development of park facilities. The area was designated a National Historic Landmark District in 1987.[146][147]

Wildfires and culturally modified trees

During the years 1996 to 2003, the park suffered from several wildfires.[148] The fires, many of which were started by lightning during times of drought, burned 28,340 acres (11,470 ha) of forest, more than half the park. The fires also damaged many archaeological sites and park buildings. They were named: Chapin V (1996), Bircher and Pony (2000), Long Mesa (2002), and the Balcony House Complex fires (2003), which were five fires that began on the same day. The Chapin V and Pony fires destroyed two rock art sites, and the Long Mesa fire nearly destroyed the museum – the first one ever built in the National Park System – and Spruce Tree House, the third largest cliff dwelling in the park.[149]

Prior to the fires of 1996 to 2003, archaeologists had surveyed approximately ninety percent of the park. Dense undergrowth and tree cover kept many ancient sites hidden from view, but after the Chapin V, Bircher and Pony fires, 593 previously undiscovered sites were revealed – most of them date to the Basketmaker III and Pueblo I periods. Also uncovered during the fires were extensive water containment features, including 1,189 check dams, 344 terraces, and five reservoirs that date to the Pueblo II and III periods.In February 2008, the Colorado Historical Society decided to invest a part of its $7 million (equivalent to $9,728,000 in 2023) budget into a culturally modified trees project in the national park.[150]

Ute Mountain Tribal Park

The Ute Mountain Tribal Park, adjoining Mesa Verde National Park to the east of the mountains, is approximately 125,000 acres (51,000 ha) along the Mancos River. Hundreds of surface sites, cliff dwellings, petroglyphs, and wall paintings of Ancestral Puebloan and Ute cultures are preserved in the park. Native American Ute tour guides provide background information about the people, culture, and history of the park lands. National Geographic Traveler chose it as one of "80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century", one of only nine places selected in the US.[151]

Key sites

In addition to the cliff dwellings, Mesa Verde boasts a number of mesa-top ruins.[152] Examples open to public access include the Far View Complex and Cedar Tree Tower on Chapin Mesa, and Badger House Community, on Wetherill Mesa.[153]

Balcony House

Balcony House is set on a high ledge facing east. Its 45 rooms and 2 kivas would have been cold during the winter. Visitors on ranger-guided tours enter by climbing a 32 ft (10 m) ladder and crawling through a small 12 ft (4 m) tunnel. The exit, a series of toe-holds in a cleft of the cliff, was believed to be the only entry and exit route for the cliff dwellers, which made the small village easy to defend and secure. One log was dated at 1278, so it was likely built not long before the Mesa Verde people migrated out of the area.[154][155] It was officially excavated in 1910 by Jesse L. Nusbaum, who was the first National Park Service Archeologist and one of the first Superintendents of Mesa Verde National Park.[156][157] Visitors can enter Balcony House only through a ranger-guided tour, which involves numerous ladders up the cliff face and crawling through a small tunnel.[158]

-

Balcony House tour: (1) entrance 32 ft (10 m) ladder, (2) 12 ft (4 m) tunnel, (3-5) exit up 60 ft (18 m) cliff face

-

Emmett Harryson, a Navajo, at a T-shaped doorway at Balcony House (1929)

Cliff Palace

This multi-storied ruin, the best-known cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde, is located in the largest alcove in the center of the Great Mesa. It was south- and southwest-facing, providing greater warmth from the sun in the winter. Dating back more than 700 years, the dwelling is constructed of sandstone, wooden beams, and mortar.[159] Many of the rooms were brightly painted.[160][161] Cliff Palace was home to approximately 125 people, but was likely an important part of a larger community of sixty nearby pueblos, which housed a combined six hundred or more people. With 23 kivas and 150 rooms, Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park.[32]

Long House

Located on the Wetherill Mesa, Long House is the second-largest Pueblonian village; approximately 150 people lived there. The location was excavated from 1959 through 1961, as part of the Wetherhill Mesa Archaeological Project.[162] Long House was built c. 1200; it was occupied until 1280. The cliff dwelling features 150 rooms, a kiva, a tower, and a central plaza.[163] Its rooms are not clustered like typical cliff dwellings. Stones were used without shaping for fit and stability. Two overhead ledges contain storage space for grain. One ledge seems to include an overlook with small holes in the wall to see the rest of the village below. A spring is accessible within several hundred feet, and seeps are located in the rear of the village.[164]

Mug, Oak Tree, Spruce Tree, and Square Tower houses

Mug House is located on Wetherill Mesa; it contains 94 rooms, a large kiva, and a nearby reservoir. It received its name from four mugs the Charles Mason and the Wetherill brothers found strung together at the site.[165] Oak Tree House and neighboring Fire Temple can be visited via a 2-hour ranger-guided hike.[166] Spruce Tree House is the third-largest village, within several hundred feet of a spring, and had 130 rooms and eight kivas. It was constructed sometime between 1211 and 1278. It is believed anywhere from 60 to 80 people lived there at one time.[167] Because of its protective location, it is well preserved.[168][167] The short trail to Spruce Tree House begins at the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum.[169] The Square Tower House is one of the stops on the Mesa Top Loop Road driving tour.[169] The tower is the tallest structure in Mesa Verde.[170]

See also

![]() Media related to Mesa Verde National Park at Wikimedia Commons (image gallery)

Media related to Mesa Verde National Park at Wikimedia Commons (image gallery)

National monuments with ruins/cliff dwellings in the Southwestern United States:

References

- Notes

- ^ Corn was introduced to the Great Sage Plain, the regions north and west of Mesa Verde, from Mexico.[10]

- ^ Donna Glowacki refutes this position, suggesting that the people of Aztec never achieved the wide-spread influence of Chaco Canyon. She believes the relationship between Mesa Verde and Aztec was more likely one of competition and conflict, versus religious or social hegemony.[30]

- ^ The earliest known evidence for large-scale violence in the region was uncovered in southeastern Utah. Future Mesa Verde rediscoverer, Richard Wetherill, then leading the Hyde Exploring Expedition, located the site, now called "Cave 7", in which the bodies of nearly 100 men, women, and children were found. They date to the late Basketmaker II period (200 BC to 500 AD). Evidence of defensive structures, such as palisades and stockades, dating to the 7th and 11th centuries have been uncovered near ancient Puebloan farmsteads.[51]

- ^ When the Spanish first settled in the area in 1598, they proposed that the Utes and Navajo had driven the Ancestral Puebloans away from Mesa Verde.[59] In 1891, Gustaf Nordenskiöld proposed that the Puebloans had been driven away from the area by hostile intruders. In the early 20th century, Jesse Walter Fewkes theorized that climate change had adversely affected water supplies in the region, which led to widespread crop failure and the rapid depopulation of the area. The last two theories remain at the foreground of the archaeological investigation of Mesa Verde.[60]

- ^ Contemporary Native Americans do not describe the region as abandoned, but rather view it as a stage in the area's ongoing indigenous culture.[60]

- ^ During this time, the entirety of the Zuni people are believed to have migrated to western New Mexico. Archaeological evidence suggests that another large group of Puebloans migrated approximately 200 miles (320 km) to southwestern New Mexico, where they built structures that are now known as Pinnacle Ruin.[66]

- ^ Similar structures are used by modern Pueblo people.[69]

- ^ Painted wavy lines in the square tower at Cliff Palace average 18.6 marks each, suggesting that people recorded four of these events there.[78] Jesse Walter Fewkes named the building Sun Temple after finding rock art in the southwest corner of the site depicting the sun.[75]

- ^ Mancos shale was the most commonly used clay in the region, particularly for non-decorated gray wares.[89]

- Citations

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ "Mesa Verde National Park | Mesa Verde Country Colorado". mesaverdecountry.com. Mesa Verde Country Visitor Information Bureau. Archived from the original on January 2, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "Mesa Verde National Park | World Heritage Site | Discover a place that time has forgotten" (PDF). visitmesaverde.com. Aramark. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 9–10: Paleo-Indians; Lekson 2015, p. 105: southeastern Utah to northwestern New Mexico.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Charles 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b Charles 2006, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Naranjo 2006, p. 54.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Charles 2006, pp. 14–15: end of Basketmaker II; Wilshusen 2006, p. 19 beginning of Basketmaker III.

- ^ Ortman 2006, p. 102.

- ^ a b Wilshusen 2006, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, p. 383.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, pp. 383–85.

- ^ Wilshusen 2006, p. 23.

- ^ Wilshusen 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Lipe 2006, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Wilshusen 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Wilshusen 2006, pp. 19, 24–25.

- ^ Wilshusen 2006, p. 26.

- ^ a b Wilshusen 2006, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e Lipe 2006, p. 29.

- ^ a b Adams 2006, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Lipe 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Lipe 2006, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Lekson, Stephen. The Chaco Meridian: One Thousand Years of Political and Religious Power in the Ancient Southwest. Rowman & Littlefield, 2015

- ^ Varien 2006, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e Varien 2006, p. 44.

- ^ Lipe 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b Varien 2006, p. 41.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, pp. 385–86, 398–99.

- ^ Billman, Brian (2017). "Cannibalism, Warfare, and Drought in the Mesa Verde Region during the Twelfth Century A.D." American Antiquity. 65 (1): 145–178. doi:10.2307/2694812. JSTOR 2694812. PMID 17674506. S2CID 19252687.

- ^ Lipe 2006, p. 36.

- ^ a b Varien 2006, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Varien 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Varien 2006, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, p. 385.

- ^ Lekson 2015, p. 105.

- ^ a b Kantner 2004, pp. 161–66.

- ^ Varien 2006, pp. 40, 46.

- ^ Glowacki, Neff & Glascock 1998, p. 218.

- ^ a b c Cameron 2006, p. 140.

- ^ Varien 2006, p. 46.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, p. 128.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Cameron 2006, pp. 140–41.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, pp. 386, 398.

- ^ Lipe 2006, p. 37.

- ^ a b Kuckelman 2006, p. 127.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, p. 134.

- ^ Kohler 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Casey 1993, p. 220.

- ^ Watson 1961, p. 156.

- ^ Varien 2006, p. 45.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Cameron 2006, p. 139.

- ^ Cameron 2006, pp. 139–41.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 74.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, pp. 395–98.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Cameron 2006, pp. 144–45.

- ^ Cameron 2006, p. 142.

- ^ Hurst & Till 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Hurst & Till 2006, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hurst & Till 2006, p. 80.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 13, 47–59.

- ^ a b c Wenger 1991, pp. 9–13, 24.

- ^ Lekson 2015, pp. 158, 175–80.

- ^ Phillips, David A., Jr., 2000, "The Chaco Meridian: A skeptical analysis" paper presented to the 65th annual meeting of the Society of American Archaeology, Philadelphia.

- ^ a b Hurst & Till 2006, p. 83.

- ^ a b Malville 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Malville 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Malville 2006, pp. 85, 90–91.

- ^ Malville 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Adams 2006, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Ortman 2006, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Lipe 2006, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Hurst & Till 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Wright 2006, pp. 123–24.

- ^ Benson et al. 2014, pp. 164–79.

- ^ a b c Adams 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Kohler 2006, p. 72.

- ^ Adams 2006, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Ortman 2006, p. 101.

- ^ a b Lang 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Ortman 2006, pp. 104–06.

- ^ a b Glowacki, Neff & Glascock 1998, pp. 231, 234, 237.

- ^ a b Glowacki, Neff & Glascock 1998, p. 238.

- ^ Ortman 2006, pp. 103–05.

- ^ Ortman 2006, pp. 106.

- ^ Lang 2006, p. 62.

- ^ a b Ortman 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Ortman 2006, pp. 106–07.

- ^ a b National Park Service 1986, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Hurst & Till 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Kuckelman 2006, p. 132.

- ^ Cole 2006, pp. 93–98.

- ^ "USDA Interactive Plant Hardiness Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, p. 386.

- ^ Adams 2006, pp. 1–3.

- ^ "U.S. Potential Natural Vegetation, Original Kuchler Types, v2.0 (Spatially Adjusted to Correct Geometric Distortions)". Data Basin. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ National Park Service (h).

- ^ a b c d Harris, Tuttle & Tuttle 2004, pp. 91–102.

- ^ a b Wenger 1991, p. 77.

- ^ Watson 1961, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Treimer, Katieri (1989), "Site Research Report, Site Number 916, Southwest Colorado", Earth Metrics and SRI International, for Contel Systems and the United States Air Force

- ^ a b c d Reynolds & Reynolds 2006.

- ^ a b c Robertson 2003, pp. 61–72.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 79.

- ^ a b Watson 1961, pp. 133–37.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 81.

- ^ Watson 1961, p. 27.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 2009, p. W12.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Rancourt, Linda M (Winter 2006). "Cultural Celebration". National Parks. 80 (1): 4. ISSN 0276-8186. Retrieved July 8, 2017 – via EBSCO's Master File Complete (subscription required)

{{cite journal}}: External link in|postscript= - ^ Wenger 1991, p. 85.

- ^ Webb, Boyer & Turner 2010, p. 302.

- ^ United States Department of the Interior, pp. 486–487, 503.

- ^ "British Museum – Collection Mesa Verde". British Museum.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b National Park Service (a).

- ^ "Mesa Verde Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ "Mesa Verde Wilderness Area". Colorado Wilderness. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ^ Casey 1993, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service (d).

- ^ a b Nordby 2006, p. 111.

- ^ "Montezuma County, Colorado", National Register of Historic Places, retrieved August 7, 2015

- ^ Harden 2015.

- ^ Keller 1998, pp. 30–42.

- ^ Burnham, Philip (2000). Indian Country, God's Country: Native Americans and the National Parks. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. pp. 62–66. ISBN 155963667X.

- ^ a b c Mesa Verde Trip Planner. Mesa Verde National Park Retrieved September 22, 2011

- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved June 4, 2015. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ Cordell et al. 2007, p. 380: 4,372 documented sites; Nordby 2006, p. 111: 600 cliff dwellings.

- ^ "Archeological adventure". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ ZIP Code Lookup Archived January 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine United States Postal Service Retrieved January 2, 2007

- ^ Laura Soullière Harrison (1986). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters, Museum, Post Office, Ranger Dormitory, Superintendents Residence, and Community Building / Mesa Verde Administrative District (Preferred)". National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying 51 photos, exterior and interior, from 1985 (7.88 MB) - ^ ""Architecture in the Parks: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study: Mesa Verde Administrative District", by Laura Soullière Harrison". National Historic Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Mesa Verde Fire History. Mesa Verde National Park Retrieved September 24, 2011

- ^ Bell 2006, p. 119.

- ^ State Historical Fund awards more than $7M in grants, Denver Business Journal, Feb 14, 2008.

- ^ Ute Mountain Tribal Park. Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Ute Mountain Tribal Park Retrieved June 18, 2011

- ^ Casey 1993, pp. 220–21.

- ^ Casey 1993, p. 222.

- ^ Casey 1993, pp. 225–26.

- ^ Wenger 1991, pp. 55–56.

- ^ McManamon, Francis P. (March 2009). "Jesse L. Nusbaum—First National Park Service Archeologist" (PDF).

- ^ "Mesa Verde Balcony House". Aramark: Parks and Destinations. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ National Park Service (b).

- ^ Cliff House Visit Mesa Verde Retrieved October 16, 2011

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 51.

- ^ Watson 1961, pp. 3, 29, 31, 37.

- ^ National Park Service (c).

- ^ Glowacki, Neff & Glascock 1998, p. 220.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 57.

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 59.

- ^ National Park Service (g).

- ^ a b National Park Service (e).

- ^ Wenger 1991, p. 52.

- ^ a b National Park Service (f).

- ^ Noel 2015, p. 36.

- Bibliography

- Adams, Karen R. (2006), "Through the Looking Glass", in Nobel, David Grant (ed.), The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Puebloan Archaeology, School of American Research Press, pp. 1–7, ISBN 978-1-930618-75-6

- Bell, Julie (2006), "Fire and Archeology on Mesa Verde", in Nobel, David Grant (ed.), The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Puebloan Archaeology, School of American Research Press, pp. 118–21, ISBN 978-1-930618-75-6

- Benson, L.V.; Griffin, E.R.; Stein, J.R.; Friedman, R.A.; Andrae, S.W. (2014), "Mummy Lake: An Unroofed Ceremonial Structure Within a Large-scale Ritual Landscape", Journal of Archaeological Science, 44: 164–79, Bibcode:2014JArSc..44..164B, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.01.021, S2CID 161578889

- Cameron, Catherine M. (2006), "Leaving Mesa Verde", in Nobel, David Grant (ed.), The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Puebloan Archaeology, School of American Research Press, pp. 139–47, ISBN 978-1-930618-75-6

- Casey, Robert L. (1993) [1983], High Journey to the Southwest, The Globe Pequot Press, ISBN 978-1-56440-151-9