| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

The Nineteenth Amendment (Amendment XIX) to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

Before 1776, women had a vote in several of the colonies in what would become the United States, but by 1807 every state constitution had denied women even limited suffrage. Organizations supporting women's rights became more active in the mid-19th century and, in 1848, the Seneca Falls convention adopted the Declaration of Sentiments, which called for equality between the sexes and included a resolution urging women to secure the vote. Pro-suffrage organizations used a variety of tactics including legal arguments that relied on existing amendments. After those arguments were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, suffrage organizations, with activists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, called for a new constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the same right to vote possessed by men.

By the late 19th century, new states and territories, particularly in the West, began to grant women the right to vote. In 1878, a suffrage proposal that would eventually become the Nineteenth Amendment was introduced to Congress, but was rejected in 1887. In the 1890s, suffrage organizations focused on a national amendment while still working at state and local levels. Lucy Burns and Alice Paul emerged as important leaders whose different strategies helped move the Nineteenth Amendment forward. Entry of the United States into World War I helped to shift public perception of women's suffrage. The National American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Carrie Chapman Catt, supported the war effort, making the case that women should be rewarded with enfranchisement for their patriotic wartime service. The National Woman's Party staged marches, demonstrations, and hunger strikes while pointing out the contradictions of fighting abroad for democracy while limiting it at home by denying women the right to vote. The work of both organizations swayed public opinion, prompting President Woodrow Wilson to announce his support of the suffrage amendment in 1918. It passed in 1919 and was adopted in 1920, withstanding two legal challenges, Leser v. Garnett and Fairchild v. Hughes.

The Nineteenth Amendment enfranchised 26 million American women in time for the 1920 U.S. presidential election, but the powerful women's voting bloc that many politicians feared failed to fully materialize until decades later. Additionally, the Nineteenth Amendment failed to fully enfranchise African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, and Native American women (see § Limitations). Shortly after the amendment's adoption, Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party began work on the Equal Rights Amendment, which they believed was a necessary additional step towards equality.

Text

The Nineteenth Amendment provides:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[1]

Background

Early woman suffrage efforts (1776–1865)

The United States Constitution, adopted in 1789, left the boundaries of suffrage undefined. The only directly elected body created under the original Constitution was the U.S. House of Representatives, for which voter qualifications were explicitly delegated to the individual states.[note 1] While women had the right to vote in several of the pre-revolutionary colonies in what would become the United States, after 1776, with the exception of New Jersey, all states adopted constitutions that denied voting rights to women. New Jersey's constitution initially granted suffrage to property-holding residents, including single and married women, but the state rescinded women's voting rights in 1807 and did not restore them until New Jersey ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.[3]

While scattered movements and organizations dedicated to women's rights existed previously, the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York is traditionally held as the start of the American women's rights movement. Attended by nearly 300 women and men, the convention was designed to "discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women", and culminated in the adoption of the Declaration of Sentiments.[4] Signed by 68 women and 32 men, the ninth of the document's twelve resolved clauses reads, "Resolved, That it is the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves their sacred right to the elective franchise."[5] Conveners Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton became key early leaders in the U.S. women's suffrage movement, often referred to at the time as the "woman suffrage movement".[6][page needed][7] Mott's support of women's suffrage stemmed from a summer spent with the Seneca Nation, one of the six tribes in the Iroquois Confederacy, where women had significant political power, including the right to choose and remove chiefs and veto acts of war.[8]

Activism addressing federal women's suffrage was minimal during the Civil War. In 1865, at the conclusion of the war, a "Petition for Universal Suffrage", signed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, among others, called for a national constitutional amendment to "prohibit the several states from disenfranchising any of their citizens on the ground of sex".[9] The campaign was the first national petition drive to feature woman suffrage among its demands.[10] While suffrage bills were introduced into many state legislatures during this period, they were generally disregarded and few came to a vote.[11]

Reconstruction Amendments and woman suffrage (1865–1877)

The women's suffrage movement, delayed by the American Civil War, resumed activities during the Reconstruction era (1865–1877). Two rival suffrage organizations formed in 1869: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone.[12][13] The NWSA's main effort was lobbying Congress for a women's suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The AWSA generally focused on a long-term effort of state campaigns to achieve women's suffrage on a state-by-state basis.[14]

During the Reconstruction era, women's rights leaders advocated for inclusion of universal suffrage as a civil right in the Reconstruction Amendments (the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments). Some unsuccessfully argued that the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibited denying voting rights "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude",[15] implied suffrage for women.[16] Despite their efforts, these amendments did not enfranchise women.[12][17] Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly discriminated between men and women by only penalizing states which deprived adult male citizens of the vote.[note 2]

The NWSA attempted several unsuccessful court challenges in the mid-1870s.[19] Their legal argument, known as the "New Departure" strategy, contended that the Fourteenth Amendment (granting universal citizenship) and Fifteenth Amendment (granting the vote irrespective of race) together guaranteed voting rights to women.[20] The U.S. Supreme Court rejected this argument. In Bradwell v. Illinois[21] the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Supreme Court of Illinois's refusal to grant Myra Bradwell a license to practice law was not a violation of the U.S. Constitution and refused to extend federal authority in support of women's citizenship rights.[note 3] In Minor v. Happersett[23] the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not provide voting rights to U.S. citizens; it only guaranteed additional protection of privileges to citizens who already had them. If a state constitution limited suffrage to male citizens of the United States, then women in that state did not have voting rights.[22] After U.S. Supreme Court decisions between 1873 and 1875 denied voting rights to women in connection with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, suffrage groups shifted their efforts to advocating for a new constitutional amendment.[20]

Continued settlement of the western frontier, along with the establishment of territorial constitutions, allowed the women's suffrage issue to be raised as the western territories progressed toward statehood. Through the activism of suffrage organizations and independent political parties, women's suffrage was included in the constitutions of Wyoming Territory (1869) and Utah Territory (1870).[17][24] Women's suffrage in Utah was revoked in 1887, when Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act in 1887 that also prohibited polygamy; it was not restored in Utah until it achieved statehood in 1896.[13][24]

Post-Reconstruction (1878–1910)

Existing state legislatures in the West, as well as those east of the Mississippi River, began to consider suffrage bills in the 1870s and 1880s. Several held voter referendums, but they were unsuccessful until the suffrage movement was revived in the 1890s.[19] Full women's suffrage continued in Wyoming after it became a state in 1890. Colorado granted partial voting rights that allowed women to vote in school board elections in 1893 and Idaho granted women suffrage in 1896. Beginning with Washington in 1910, seven more western states passed women's suffrage legislation, including California in 1911, Oregon, Arizona, and Kansas in 1912, Alaska Territory in 1913, and Montana and Nevada in 1914. All states that were successful in securing full voting rights for women before 1920 were located in the West.[13][25]

A federal amendment intended to grant women the right to vote was introduced in the U.S. Senate for the first time in 1878 by Aaron A. Sargent, a Senator from California who was a women's suffrage advocate.[26] Stanton and other women testified before the Senate in support of the amendment.[27] The proposal sat in a committee until it was considered by the full Senate and rejected in a 16-to-34 vote in 1887.[28] An amendment proposed in 1888 in the U.S. House of Representatives called for limited suffrage for women who were spinsters or widows who owned property.[29]

By the 1890s, suffrage leaders began to recognize the need to broaden their base of support to achieve success in passing suffrage legislation at the national, state, and local levels. While western women, state suffrage organizations, and the AWSA concentrated on securing women's voting rights for specific states, efforts at the national level persisted through a strategy of congressional testimony, petitioning, and lobbying.[30][31] After the AWSA and NWSA merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the group directed its efforts to win state-level support for suffrage.[32] Suffragists had to campaign publicly for the vote in order to convince male voters, state legislators, and members of Congress that American women wanted to be enfranchised and that women voters would benefit American society. Suffrage supporters also had to convince American women, many of whom were indifferent to the issue, that suffrage was something they wanted. Apathy among women was an ongoing obstacle that the suffragists had to overcome through organized grassroots efforts.[33] Despite the suffragists' efforts, no state granted women suffrage between 1896 and 1910, and the NAWSA shifted its focus toward passage of a national constitutional amendment.[32] Suffragists also continued to press for the right to vote in individual states and territories while retaining the goal of federal recognition.[28]

African-American woman suffrage efforts

Thousands of African-American women were active in the suffrage movement, addressing issues of race, gender, and class, as well as enfranchisement,[34] often through the church but eventually through organizations devoted to specific causes.[35] While white women sought the vote to gain an equal voice in the political process, African-American women often sought the vote as a means of racial uplift and as a way to effect change in the post-Reconstruction era.[36][37] Notable African-American suffragists such as Mary Church Terrell, Sojourner Truth, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Fannie Barrier Williams, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett advocated for suffrage in tandem with civil rights for African-Americans.[34]

As early as 1866, in Philadelphia, Margaretta Forten and Harriet Forten Purvis helped to found the Philadelphia Suffrage Association; Purvis would go on to serve on the executive committee of the American Equal Rights Association (AERA), an organization that supported suffrage for women and for African-American men.[38] A national movement in support of suffrage for African-American women began in earnest with the rise of the black women's club movement.[36] In 1896, club women belonging to various organizations promoting women's suffrage met in Washington, D.C. to form the National Association of Colored Women, of which Frances E.W. Harper, Josephine St. Pierre, Harriet Tubman, and Ida B. Wells Barnett were founding members.[39] Led by Mary Church Terrell, it was the largest federation of African-American women's clubs in the nation.[36] After 1914 it became the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs.[40]

When the Fifteenth Amendment enfranchised African-American men, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony abandoned the AERA, which supported universal suffrage, to found the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, saying black men should not receive the vote before white women.[38] In response, African-American suffragist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and others joined the American Woman Suffrage Association, which supported suffrage for women and for black men. Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the second African-American woman to receive a degree from Howard University Law School, joined the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1878 when she delivered their convention's keynote address.[41] Tensions between African-American and white suffragists persisted, even after the NWSA and AWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1890.[38] By the early 1900s, white suffragists often adopted strategies designed to appease the Southern states at the expense of African-American women.[42][43][page needed] At conventions in 1901 and 1903, in Atlanta and New Orleans, NAWSA prevented African Americans from attending. At the 1911 national NAWSA conference, Martha Gruening asked the organization to formally denounce white supremacy. NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw refused, saying she was "in favor of colored people voting", but did not want to alienate others in the suffrage movement.[44] Even NAWSA's more radical Congressional Committee, which would become the National Woman's Party, failed African-American women, most visibly by refusing to allow them to march in the nation's first suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. While the NAWSA directed Paul not to exclude African-American participants, 72 hours before the parade African-American women were directed to the back of the parade; Ida B. Wells defied these instructions and joined the Illinois unit, prompting telegrams of support.[44]

Mary B. Talbert, a leader in both the NACW and NAACP, and Nannie Helen Burroughs, an educator and activist, contributed to an issue of the Crisis, published by W. E. B. Du Bois in August 1915.[44] They wrote passionately about African-American women's need for the vote. Burroughs, asked what women could do with the ballot, responded pointedly: "What can she do without it?"[44]

Proposal and ratification

A new focus on a federal amendment

In 1900, Carrie Chapman Catt succeeded Susan B. Anthony as the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Catt revitalized NAWSA, turning the focus of the organization to the passage of the federal amendment while simultaneously supporting women who wanted to pressure their states to pass suffrage legislation. The strategy, which she later called "The Winning Plan", had several goals: women in states that had already granted presidential suffrage (the right to vote for the President) would focus on passing a federal suffrage amendment; women who believed they could influence their state legislatures would focus on amending their state constitutions and Southern states would focus on gaining primary suffrage (the right to vote in state primaries).[45] Simultaneously, the NAWSA worked to elect congressmen who supported suffrage for women.[42] By 1915, NAWSA was a large, powerful organization, with 44 state chapters and more than two million members.[45]

In a break with NAWSA, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns founded the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage in 1913 to pressure the federal government to take legislative action. One of their first acts was to organize a women's suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. The procession of more than 5,000 participants, the first of its kind, attracted a crowd of an estimated 500,000, as well as national media attention, but Wilson took no immediate action. In March 1917, the Congressional Union joined with Women's Party of Western Voters to form the National Woman's Party (NWP), whose aggressive tactics included staging more radical acts of civil disobedience and controversial demonstrations to draw more attention to the women's suffrage issue.[46]

Woman suffrage and World War I patriotism

When World War I started in 1914, women in eight states had already won the right to vote, but support for a federal amendment was still tepid. The war provided a new urgency to the fight for the vote. When the U.S. entered World War I, Catt made the controversial decision to support the war effort, despite the widespread pacifist sentiment of many of her colleagues and supporters.[47] As women joined the labor force to replace men serving in the military and took visible positions as nurses, relief workers, and ambulance drivers[48] to support the war effort, NAWSA organizers argued that women's sacrifices made them deserving of the vote. By contrast, the NWP used the war to point out the contradictions of fighting for democracy abroad while restricting it at home.[42] In 1917, the NWP began picketing the White House to bring attention to the cause of women's suffrage.

In 1914 the constitutional amendment proposed by Sargent, which was nicknamed the "Susan B. Anthony Amendment", was once again considered by the Senate, where it was again rejected.[28] In April 1917 the "Anthony Amendment", which eventually became the Nineteenth Amendment, was reintroduced in the House and Senate. Picketing NWP members, nicknamed the "Silent Sentinels", continued their protests on the sidewalks outside the White House. On July 4, 1917, police arrested 168 of the protesters, who were sent to prison in Lorton, Virginia. Some of these women, including Lucy Burns and Alice Paul, went on hunger strikes; some were force-fed while others were otherwise harshly treated by prison guards. The release of the women a few months later was largely due to increasing public pressure.[46]

Final congressional challenges

In 1918, President Wilson faced a difficult midterm election and would have to confront the issue of women's suffrage directly.[42] Fifteen states had extended equal voting rights to women and, by this time, the President fully supported the federal amendment.[49][50] A proposal brought before the House in January 1918 passed by only one vote. The vote was then carried into the Senate where Wilson made an appeal on the Senate floor, an unprecedented action at the time.[51] In a short speech, the President tied women's right to vote directly to the war, asking, "Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?"[42] On September 30, 1918, the proposal fell two votes short of passage, prompting the NWP to direct campaigning against senators who had voted against the amendment.[50]

Between January 1918 and June 1919, the House and Senate voted on the federal amendment five times.[42][51][52] Each vote was extremely close and Southern Democrats continued to oppose giving women the vote.[51] Suffragists pressured President Wilson to call a special session of Congress and he agreed to schedule one for May 19, 1919. On May 21, 1919, the amendment passed the House 304 to 89, with 42 votes more than was necessary.[53] On June 4, 1919, it was brought before the Senate and, after Southern Democrats abandoned a filibuster,[42] 36 Republican senators were joined by 20 Democrats to pass the amendment with 56 yeas, 25 nays, and 14 not voting. The final vote tally was:[54]

- 20 Democrats Yea

- 17 Democrats Nay

- 9 Democrats Not voting/abstained

- 36 Republicans Yea

- 8 Republicans Nay

- 5 Republicans Not voting/abstained

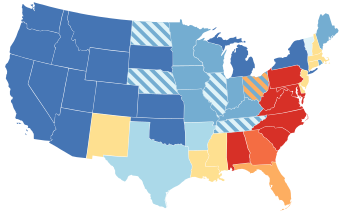

Ratification

Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul immediately mobilized members of the NAWSA and NWP to pressure states to ratify the amendment. Within a few days, the legislatures of Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan did so. It is arguable which State was considered first to ratify the amendment. While Illinois's legislature passed the legislation an hour prior to Wisconsin, Wisconsin's delegate, David James, arrived earlier and was presented with a statement establishing Wisconsin as the first to ratify.[57]

By August 2, 1919, 14 states had approved ratification. By the end of 1919, 22 had ratified the amendment.[53] In other states support proved more difficult to secure. Much of the opposition to the amendment came from Southern Democrats; only two former Confederate states (Texas and Arkansas) and three border states voted for ratification,[42] with Kentucky and West Virginia not doing so until 1920. Alabama and Georgia were the first states to defeat ratification. The governor of Louisiana worked to organize 13 states to resist ratifying the amendment. The Maryland legislature refused to ratify the amendment and attempted to prevent other states from doing so. Carrie Catt began appealing to Western governors, encouraging them to act swiftly. By the end of 1919, a total of 22 states had ratified the amendment.[53]

Resistance to ratification took many forms: anti-suffragists continued to say the amendment would never be approved by the November 1920 elections and that special sessions were a waste of time and effort. Other opponents to ratification filed lawsuits requiring the federal amendment to be approved by state referendums. By June 1920, after intense lobbying by both the NAWSA and the NWP, the amendment was ratified by 35 of the necessary 36 state legislatures.[53] Ratification would be determined by Tennessee. In the middle of July 1919, both opponents and supporters of the Anthony Amendment arrived in Nashville to lobby the General Assembly. Carrie Catt, representing the NAWSA, worked with state suffragist leaders, including Anne Dallas Dudley and Abby Crawford Milton. Sue Shelton White, a Tennessee native who had participated in protests at the White House and toured with the Prison Special, represented the NWP.[58] Opposing them were the "Antis", in particular, Josephine Pearson, state president of the Southern Women's Rejection League of the Susan. B. Anthony Amendment, who had served as dean and chair of philosophy at Christian College in Columbia.[43][page needed] Pearson was assisted by Anne Pleasant, president of the Louisiana Women's Rejection League and the wife of a former Louisiana governor. Especially in the South, the question of women's suffrage was closely tied to issues of race.[59] While both white and black women worked toward women's suffrage, some white suffragists tried to appease southern states by arguing that votes for women could counter the black vote, strengthening white supremacy.[42] For the anti-suffragists in the south (the "Antis"), the federal amendment was viewed as a "Force Bill", one that Congress could use to enforce voting provisions not only for women, but for African-American men who were still effectively disenfranchised even after passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Carrie Catt warned suffrage leaders in Tennessee that the "Anti-Suffs" would rely on "lies, innuendoes, and near truths", raising the issue of race as a powerful factor in their arguments.[43][page needed]

Prior to the start of the General Assembly session on August 9, both supporters and opponents had lobbied members of the Tennessee Senate and House of Representatives. Though the Democratic governor of Tennessee, Albert H. Roberts, supported ratification, most lawmakers were still undecided. Anti-suffragists targeted members, meeting their trains as they arrived in Nashville to make their case. When the General Assembly convened on August 9, both supporters and opponents set up stations outside of chambers, handing out yellow roses to suffrage supporters and red roses to the "Antis". On August 12, the legislature held hearings on the suffrage proposal; the next day the Senate voted 24–5 in favor of ratification. As the House prepared to take up the issue of ratification on August 18, lobbying intensified.[58] House Speaker Seth M. Walker attempted to table the ratification resolution, but was defeated twice with a vote of 48–48. The vote on the resolution would be close. Representative Harry Burn, a Republican, had voted to table the resolution both times. When the vote was held again, Burn voted yes. The 24-year-old said he supported women's suffrage as a "moral right", but had voted against it because he believed his constituents opposed it. In the final minutes before the vote, he received a note from his mother, urging him to vote yes. Rumors immediately circulated that Burn and other lawmakers had been bribed, but newspaper reporters found no evidence of this.[58]

The same day ratification passed in the General Assembly, Speaker Walker filed a motion to reconsider. When it became clear he did not have enough votes to carry the motion, representatives opposing suffrage boarded a train, fleeing Nashville for Decatur, Alabama to block the House from taking action on the reconsideration motion by preventing a quorum. Thirty-seven legislators fled to Decatur, issuing a statement that ratifying the amendment would violate their oath to defend the state constitution.[58] The ploy failed. Speaker Walker was unable to muster any additional votes in the allotted time. When the House reconvened to take the final procedural steps that would reaffirm ratification, Tennessee suffragists seized an opportunity to taunt the missing Anti delegates by sitting at their empty desks. When ratification was finally confirmed, a suffragist on the floor of the House rang a miniature Liberty Bell.[43][page needed]

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee narrowly approved the Nineteenth Amendment, with 50 of 99 members of the Tennessee House of Representatives voting yes.[49][60] This provided the final ratification necessary to add the amendment to the Constitution,[61] making the United States the twenty-seventh country in the world to give women the right to vote.[13] Upon signing the ratification certificate, the Governor of Tennessee sent it by registered mail to the U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, whose office received it at 4:00 a.m. on August 26, 1920. Once certified as correct, Colby signed the Proclamation of the Women's Suffrage Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in the presence of his secretary only.[62]

Ratification timeline

Congress proposed the Nineteenth Amendment on June 4, 1919, and the following states ratified the amendment.[64][65]

- Illinois: June 10, 1919[66][67][note 4]

- Wisconsin: June 10, 1919[66][67]

- Michigan: June 10, 1919[69]

- Kansas: June 16, 1919[70]

- Ohio: June 16, 1919[71][72][73]

- New York: June 16, 1919[74]

- Pennsylvania: June 24, 1919[73]

- Massachusetts: June 25, 1919[73]

- Texas: June 28, 1919[73]

- Iowa: July 2, 1919[note 5]

- Missouri: July 3, 1919

- Arkansas: July 28, 1919[75]

- Montana: July 30, 1919;[75] August 2, 1919[note 5][note 6]

- Nebraska: August 2, 1919[75]

- Minnesota: September 8, 1919

- New Hampshire: September 10, 1919[note 5]

- Utah: September 30, 1919[76]

- California: November 1, 1919[75]

- Maine: November 5, 1919[77]

- North Dakota: December 1, 1919[75]

- South Dakota: December 4, 1919[77]

- Colorado: December 12, 1919;[75] December 15, 1919[note 5]

- Rhode Island: January 6, 1920[75] at 1:00 p.m.[78]

- Kentucky: January 6, 1920[75] at 4:00 p.m.[79]

- Oregon: January 12, 1920[77]

- Indiana: January 16, 1920[80][81]

- Wyoming: January 26, 1920[82][note 7]

- Nevada: February 7, 1920[75]

- New Jersey: February 9, 1920[82][note 8]

- Idaho: February 11, 1920[82]

- Arizona: February 12, 1920[82]

- New Mexico: February 16, 1920[82][note 9]

- Oklahoma: February 23, 1920[83][note 10]

- West Virginia: March 10, 1920, confirmed on September 21, 1920[note 11]

- Washington: March 22, 1920[note 12]

- Tennessee: August 18, 1920[86][note 13][87]

The ratification process required 36 states, and completed with the approval by Tennessee. Though not necessary for adoption, the following states subsequently ratified the amendment. Some states did not call a legislative session to hold a vote until later, others rejected it when it was proposed and then reversed their decisions years later, with the last taking place in 1984.[64][88]

- Connecticut: September 14, 1920, reaffirmed on September 21, 1920

- Vermont: February 8, 1921

- Delaware: March 6, 1923 (after being rejected on June 2, 1920)

- Maryland: March 29, 1941 (after being rejected on February 24, 1920; not certified until February 25, 1958)

- Virginia: February 21, 1952 (after being rejected on February 12, 1920)[89][90]

- Alabama: September 8, 1953 (after being rejected on September 22, 1919)

- Florida: May 13, 1969[91]

- South Carolina: July 1, 1969 (after being rejected on January 28, 1920; not certified until August 22, 1973)

- Georgia: February 20, 1970 (after being rejected on July 24, 1919)

- Louisiana: June 11, 1970 (after being rejected on July 1, 1920)

- North Carolina: May 6, 1971

- Mississippi: March 22, 1984 (after being rejected on March 29, 1920)

With Mississippi's ratification in 1984, the amendment was now ratified by all states existing at the time of its adoption in 1920.

Legal challenges

The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously upheld the amendment's validity in Leser v. Garnett.[92][93] Maryland citizens Mary D. Randolph, "'a colored female citizen' of 331 West Biddle Street",[94] and Cecilia Street Waters, "a white woman, of 824 North Eutaw Street",[94] applied for and were granted registration as qualified Baltimore voters on October 12, 1920. To have their names removed from the list of qualified voters, Oscar Leser and others brought suit against the two women on the sole grounds that they were women, arguing that they were not eligible to vote because the Constitution of Maryland limited suffrage to men[95] and the Maryland legislature had refused to vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Two months before, on August 26, 1920, the federal government had proclaimed the amendment incorporated into the Constitution.[93]

Leser said the amendment "destroyed State autonomy" because it increased Maryland's electorate without the state's consent. The Supreme Court answered that the Nineteenth Amendment had similar wording to the Fifteenth Amendment, which had expanded state electorates without regard to race for more than fifty years by that time despite rejection by six states (including Maryland).[93][96] Leser further argued that the state constitutions in some ratifying states did not allow their legislatures to ratify. The court replied that state ratification was a federal function granted under Article V of the U.S. Constitution and not subject to a state constitution's limitations. Finally, those bringing suit asserted the Nineteenth Amendment was not adopted because Tennessee and West Virginia violated their own rules of procedure. The court ruled that the point was moot because Connecticut and Vermont had subsequently ratified the amendment, providing a sufficient number of state ratifications to adopt the Nineteenth Amendment even without Tennessee and West Virginia. The court also ruled that Tennessee's and West Virginia's certifications of their state ratifications was binding and had been duly authenticated by their respective secretaries of state.[97] As a result of the court's ruling, Randolph and Waters were permitted to become registered voters in Baltimore.[93]

Another challenge to the Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was dismissed by the Supreme Court in Fairchild v. Hughes,[98][99] because the party bringing the suit, Charles S. Fairchild, came from a state that already allowed women to vote and so Fairchild lacked standing.

Effects

Women's voting behavior

Adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment enfranchised 26 million American women in time for the 1920 U.S. presidential election.[100] Many legislators feared that a powerful women's bloc would emerge in American politics. This fear led to the passage of such laws as the Sheppard–Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act of 1921, which expanded maternity care during the 1920s.[101] Newly enfranchised women and women's groups prioritized a reform agenda rather than party loyalty and their first goal was the Sheppard-Towner Act. It was the first federal social security law and made a dramatic difference before it was allowed to lapse in 1929.[102] Other efforts at the federal level in the early 1920s that related to women labor and women's citizenship rights included the establishment of a Women's Bureau in the U.S. Department of Labor in 1920 and passage of the Cable Act in 1922.[103] After the U.S. presidential election in 1924, politicians realized the women's bloc they had feared did not actually exist and they did not need to cater to what they considered as "women's issues" after all.[104] The eventual appearance of an American women's voting bloc has been tracked to various dates, depending on the source, from the 1950s[105] to 1970.[106] Around 1980, a nationwide gender gap in voting had emerged, with women usually favoring the Democratic candidate in presidential elections.[107]

According to political scientists J. Kevin Corder and Christina Wolbrecht, few women turned out to vote in the first national elections after the Nineteenth Amendment gave them the right to do so. In 1920, 36 percent of eligible women voted (compared with 68 percent of men). The low turnout among women was partly due to other barriers to voting, such as literacy tests, long residency requirements, and poll taxes. Inexperience with voting and persistent beliefs that voting was inappropriate for women may also have kept turnout low. The participation gap was lowest between men and women in swing states at the time, in states that had closer races such as Missouri and Kentucky, and where barriers to voting were lower.[108][109] By 1960, women were turning out to vote in presidential elections in greater numbers than men and a trend of higher female voting engagement has continued into 2018.[110]

Limitations

African-American women

African-Americans had gained the right to vote, but for 75 percent of them it was granted in name only, as state constitutions kept them from exercising that right.[36] Prior to the passage of the amendment, Southern politicians held firm in their convictions not to allow African-American women to vote.[111] They had to fight to secure not only their own right to vote, but the right of African-American men as well.[112]

Three million women south of the Mason–Dixon line remained disfranchised after the passage of the amendment.[111][113] Election officials regularly obstructed access to the ballot box.[114] As newly enfranchised African-American women attempted to register, officials increased the use of methods that Brent Staples, in an opinion piece for The New York Times, described as fraud, intimidation, poll taxes, and state violence.[115] In 1926, a group of women attempting to register in Birmingham, Alabama were beaten by officials.[116] Incidents such as this, threats of violence and job losses, and legalized prejudicial practices blocked women of color from voting.[117] These practices continued until the Twenty-fourth Amendment was adopted in 1962, whereby the states were prohibited from making voting conditional on poll or other taxes, paving the way to more reforms with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

African-Americans continued to face barriers preventing them from exercising their vote until the civil rights movement arose in the 1950s and 1960s, which posited voting rights as civil rights.[111][116] Nearly a thousand civil rights workers converged on the South to support voting rights as part of Freedom Summer, and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches brought further participation and support. However, state officials continued to refuse registration until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting.[114][117] For the first time, states were forbidden from imposing discriminatory restrictions on voting eligibility, and mechanisms were placed allowing the federal government to enforce its provisions.[116]

Other minority groups

Native Americans were granted citizenship by an Act of Congress in 1924,[118] but state policies prohibited them from voting. In 1948, a suit brought by World War II veteran Miguel Trujillo resulted in Native Americans gaining the right to vote in New Mexico and Arizona,[119] but some states continued to bar them from voting until 1957.[116]

Poll taxes and literacy tests kept Latina women from voting. In Puerto Rico, for example, women did not receive the right to vote until 1929, but was limited to literate women until 1935.[120] Further, the 1975 extensions of the Voting Rights Act included requiring bilingual ballots and voting materials in certain regions, making it easier for Latina women to vote.[116][117]

National immigration laws prevented Asians from gaining citizenship until 1952.[46][116][117]

Other limitations

After adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, women still faced political limitations. Women had to lobby their state legislators, bring lawsuits, and engage in letter-writing campaigns to earn the right to sit on juries. In California, women won the right to serve on juries four years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. In Colorado, it took 33 years. Women continue to face obstacles when running for elective offices, and the Equal Rights Amendment, which would grant women equal rights under the law, has yet to be passed.[121][122][123][124]

Legacy

League of Women Voters

In 1920, about six months before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, Emma Smith DeVoe and Carrie Chapman Catt agreed to merge the National American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Council of Women Voters to help newly enfranchised women exercise their responsibilities as voters. Originally only women could join the league, but in 1973 the charter was modified to include men. Today, the League of Women Voters operates at the local, state, and national level, with over 1,000 local and 50 state leagues, and one territory league in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Some critics and historians question whether creating an organization dedicated to political education rather than political action made sense in the first few years after ratification, suggesting that the League of Women Voters diverted the energy of activists.[43][page needed]

Equal Rights Amendment

Alice Paul and the NWP did not believe the Nineteenth Amendment would be enough to ensure men and women were treated equally, and in 1921 the NWP announced plans to campaign for another amendment which would guarantee equal rights not limited to voting. The first draft of the Equal Rights Amendment, written by Paul and Crystal Eastman and first named "the Lucretia Mott Amendment", stated: "No political, civil, or legal disabilities or inequalities on account of sex or on account of marriage, unless applying equally to both sexes, shall exist within the United States or any territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof."[125] Senator Charles Curtis brought it to Congress that year, but it did not make it to the floor for a vote. It was introduced in every congressional session from 1921 to 1971, usually not making it out of committee.[126]

The amendment did not have the full support of women's rights activists, and was opposed by Carrie Catt and the League of Women Voters. Whereas the NWP believed in total equality, even if that meant sacrificing benefits given to women through protective legislation, some groups like the Women's Joint Congressional Committee and the Women's Bureau believed the loss of benefits relating to safety regulations, working conditions, lunch breaks, maternity provisions, and other labor protections would outweigh what would be gained. Labor leaders like Alice Hamilton and Mary Anderson argued that it would set their efforts back and make sacrifices of what progress they had made.[127][128] In response to these concerns, a provision known as "the Hayden rider" was added to the ERA to retain special labor protections for women, and passed the Senate in 1950 and 1953, but failed in the House. In 1958, President Eisenhower called on Congress to pass the amendment, but the Hayden rider was controversial, meeting with opposition from the NWP and others who felt it undermined its original purpose.[129][130]

The growing, productive women's movements of the 1960s and 1970s renewed support for the amendment. U.S. Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan reintroduced it in 1971, leading to its approval by the House of Representatives that year. After it passed in the Senate on March 22, 1972, it went to state legislatures for ratification. Congress originally set a deadline of March 22, 1979, by which point at least 38 states needed to ratify the amendment. It reached 35 by 1977, with broad bipartisan support including both major political parties and Presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter. However, when Phyllis Schlafly mobilized conservative women in opposition, four states rescinded their ratification, although whether a state may do so is disputed.[131] The amendment did not reach the necessary 38 states by the deadline.[43][page needed] President Carter signed a controversial extension of the deadline to 1982, but that time saw no additional ratifications.

In the 1990s, ERA supporters resumed efforts for ratification, arguing that the pre-deadline ratifications still applied, that the deadline itself can be lifted, and that only three states were needed. Whether the amendment is still before the states for ratification remains disputed, but in 2014 both Virginia and Illinois state senates voted to ratify, although both were blocked in the house chambers. In 2017, 45 years after the amendment was originally submitted to states, the Nevada legislature became the first to ratify it following expiration of the deadlines. Illinois lawmakers followed in 2018.[131] Another attempt in Virginia passed the Assembly but was defeated on the state senate floor by one vote.[132] The most recent effort to remove the deadline was in early 2019, with proposed legislation from Jackie Speier, accumulating 188 co-sponsors and pending in Congress as of August 2019.[133]

Commemorations

A 7+1⁄2-ton marble slab from a Carrara, Italy, quarry carved into statue called the "Portrait Monument"[134] (originally known as the "Woman's Movement")[135] by sculptor Adelaide Johnson was unveiled at the Capitol rotunda on February 15, 1921, six months after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, on the 101st anniversary of Susan B. Anthony's birth, and during the National Woman's Party's first post-ratification national convention in Washington, D.C.[134] The Party presented it as a gift "from the women of the U.S." The monument is installed in the Capitol rotunda and features busts of Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. More than fifty women's groups with delegates from every state were represented at the dedication ceremony in 1921 that was presided over by Jane Addams. After the ceremony, the statue was moved temporarily to the Capitol crypt, where it stood for less than a month until Johnson discovered that an inscription stenciled in gold lettering on the back of the monument had been removed. The inscription read, in part: "Woman, first denied a soul, then called mindless, now arisen declares herself an entity to be reckoned. Spiritually, the woman movement ... represents the emancipation of womanhood. The release of the feminine principal in humanity, the moral integration of human evolution come to rescue torn and struggling humanity from its savage self."[134] Congress denied passage of several bills to move the statue, whose place in the crypt also held brooms and mops. In 1963, the crypt was cleaned for an exhibition of several statues including this one, which had been dubbed "The Women in the Bathtub". In 1995 on the 75th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, women's groups renewed congressional interest in the monument and on May 14, 1997, the statue was finally returned to the rotunda.[136]

On August 26, 2016, a monument commemorating Tennessee's role in providing the required 36th state ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was unveiled in Centennial Park in Nashville, Tennessee.[137] The memorial, erected by the Tennessee Suffrage Monument, Inc.[138] and created by Alan LeQuire, features likenesses of suffragists who were particularly involved in securing Tennessee's ratification: Carrie Chapman Catt; Anne Dallas Dudley; Abby Crawford Milton; Juno Frankie Pierce; and Sue Shelton White.[43][page needed][139] In June 2018, the city of Knoxville, Tennessee, unveiled another sculpture by LeQuire, this one depicting 24-year-old freshman state representative Harry T. Burn and his mother. Representative Burn, at the urging of his mother, cast the deciding vote on August 18, 1920, making Tennessee the final state needed for the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.[140]

In 2018, Utah launched a campaign called Better Days 2020 to "popularize Utah women's history". One of its first projects was the unveiling on the Salt Lake City capitol steps of the design for a license plate in recognition of women's suffrage. The commemorative license plate would be available for new or existing car registrations in the state. The year 2020 marks the centennial of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, as well as the 150th anniversary of the first women voting in Utah, which was the first state in the nation where women cast a ballot.[141]

An annual celebration of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, known as Women's Equality Day, began on August 26, 1973.[142] There usually is heightened attention and news media coverage during momentous anniversaries such as the 75th (1995) and 100th (2020), as well as in 2016 because of the presidential election.[143] For the amendment's centennial, several organizations announced large events or exhibits, including the National Constitution Center and National Archives and Records Administration.[16][144]

On the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, President Donald Trump posthumously pardoned Susan B. Anthony.[145]

Popular culture

The Nineteenth Amendment has been featured in a number of songs, films, and television programs. The 1976 song "Sufferin' Till Suffrage" from Schoolhouse Rock!, performed by Essra Mohawk and written by Bob Dorough and Tom Yohe, states, in part, "Not a woman here could vote, no matter what age, Then the Nineteenth Amendment struck down that restrictive rule ... Yes the Nineteenth Amendment Struck down that restrictive rule."[146][147] In 2018, various recording artists released an album called 27: The Most Perfect Album, featuring songs inspired by the 27 amendments to the U.S. Constitution; Dolly Parton's song inspired by the Nineteenth Amendment is called "A Woman's Right".[148][149]

One Woman, One Vote is a 1995 PBS documentary narrated by actor Susan Sarandon chronicling the Seneca Falls Convention through the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.[150][151] Another documentary was released in 1999 by filmmaker Ken Burns, Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony. It used archival footage and commentary by actors Ann Dowd, Julie Harris, Sally Kellerman and Amy Madigan.[152][153] In 2013, John Green, the best-selling author of The Fault in Our Stars, produced a video entitled Women in the 19th Century: Crash Course US History #31, providing an overview of the women's movement leading to the Nineteenth Amendment.[154][155]

The 2004 drama Iron Jawed Angels depicting suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, played by actors Hilary Swank and Frances O'Connor, respectively, as they help secure the Nineteenth Amendment.[156][157] In August 2018, former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Academy Award-winning director/producer Steven Spielberg announced plans to make a television series based on Elaine Weiss's best-selling book, The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote.[158][159]

See also

- Feminism in the United States

- History of feminism

- List of female United States presidential and vice presidential candidates

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- List of women's rights activists

- Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 (United Kingdom)

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's Equality Day

Explanatory notes

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 2, states, in part: "the electors in each state shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the state legislature"[2]

- ^ U.S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, Section 2, states, in part: "But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State." (emphasis added)[18]

- ^ Illinois courts denied Myra Bradwell's application to practice law in that state because she was a married woman and due to her marital status she could not be bound by legal contracts she made with her clients.[22]

- ^ Because of a mistake in wording in the introduction of the bill, but not the amendment itself, Illinois reaffirmed passage of the amendment on June 17 and submitted a brief to confirm that the second vote was merely a legal formality. Illinois was acknowledged by the U.S. Secretary of State as the first state to ratify the amendment.[68]

- ^ a b c d Date on which approved by governor

- ^ Montana was not only the first Western state to ratify, it was also the first state to elect a woman to Congress.[75]

- ^ Wyoming as a territory was the first globally to grant women full voting rights in 1869. In 1892, Wyoming's Theresa Jenkins was the first woman to serve as a national party convention delegate; now in 1919 she thanked Wyoming legislators for their unanimous decision to support the Nineteenth Amendment.[82]

- ^ New Jersey ratified following a rally producing a petition of over 140,000 signatures supporting the state's ratification of the amendment.[82]

- ^ New Mexico's ratification came a day after the hundredth anniversary of Susan B. Anthony's birth; suffragists used this centennial to lament that ratification had not yet been achieved.[82]

- ^ Oklahoma's ratification followed a presidential intervention urging legislators to ratify.[83]

- ^ West Virginia's ratification followed the dramatic turnaround of a voting block instigated by state Senator Jesse A. Bloch demonstrated against by suffragists from around the nation who had descended upon the state capitol.[84]

- ^ Washington was holding out to have the honor of being the last state to ratify but, in the end, a female legislator brought the matter to the floor and ratification was unanimously approved in both houses.[85]

- ^ Breaking a 48–48 vote tie, Tennessee's ratification passed when 24-year old Representative Harry T. Burn remembered his mother writing him to "help Mrs. [Carrie Chapman] Catt put the rat in ratification" by supporting suffrage.[81]

References

Citations

- ^ "19th Amendment". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "1st Amendment". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University School of Law. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Nenadic, Susan L. (May 2019). "Votes for Women: Suffrage in Michigan". Michigan History. 103 (3). Lansing, Michigan: Historical Society of Michigan: 18.

- ^ Keyssar, Alexander (2000). The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books. p. 173.

- ^ "Image 8 of Report of the Woman's Rights Convention, held at Seneca Falls, New York, July 19th and 20th, 1848. Proceedings and Declaration of Sentiments". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ DuBois, Ellen Carol (1998). Woman Suffrage and Women's Rights. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0585434711. OCLC 51232208.

- ^ Weber, Liz (June 3, 2019). "Women of color were cut out of the suffragist story. Historians say it's time for a reckoning". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Nordell, Jessica (November 24, 2016). "Millions of women voted this election. They have the Iroquois to thank". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ United States Senate (1865). Petition for Universal Suffrage which Asks for an Amendment to the Constitution that Shall Prohibit the Several States from Disenfranchising Any of Their Citizens on the Ground of Sex. File Unit: Petitions and Memorials, Resolutions of State Legislatures which were Presented, Read, or Tabled during the 39th Congress, 1865–1867. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Universal Suffrage". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ Banaszak 1996, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Banaszak 1996, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Mintz, Steven (July 2007). "The Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment". OAH Magazine of History. 21 (3). Organization of American Historians: 47. doi:10.1093/maghis/21.3.47.

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 307.

- ^ "America's Founding Documents". National Archives. October 30, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Flock, Elizabeth (September 10, 2019). "5 things you might not know about the 19th Amendment". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Mead 2004, p. 2.

- ^ "14th Amendment". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University School of Law. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Banaszak 1996, p. 8.

- ^ a b Mead 2004, pp. 35–38.

- ^ 83 U.S. 130 (1873)

- ^ a b Baker 2009, p. 3.

- ^ 88 U.S. 162 (1874)

- ^ a b Woloch 1984, p. 333.

- ^ Myres, Sandra L. (1982). Westering Women and the Frontier Experience. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 227–30. ISBN 9780826306258.

- ^ Mead 2004, p. 38.

- ^ Amar 2005, pp. 421.

- ^ a b c Kobach, Kris (May 1994). "Woman suffrage and the Nineteenth Amendment". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on November 10, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2011. See also: Excerpt from Kobach, Kris (May 1994). "Rethinking Article V: term limits and the Seventeenth and Nineteenth Amendments". Yale Law Journal. 103 (7). Yale Law School: 1971–2007. doi:10.2307/797019. JSTOR 797019.

- ^ United States House of Representatives (April 30, 1888). House Joint Resolution (H.J. Res.) 159, Proposing an Amendment to the Constitution to Extend the Right to Vote to Widows and Spinsters who are Property Holders. File Unit: Bills and Resolutions Originating in the House of Representatives during the 50th Congress, 1885–1887. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Woloch 1984, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Banaszak 1996, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b Woloch 1984, p. 334.

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 327.

- ^ a b "Perspective | It's time to return black women to the center of the history of women's suffrage". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Black Church". The Black Suffragist. Archived from the original on June 6, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (1998). African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253211767.

- ^ Goodier, S.; Pastorello, K. (2017). "A Fundamental Component: Suffrage for African American Women". Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State. ITHACA; LONDON: Cornell University Press. pp. 71–91.

- ^ a b c "African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "A National Association for Colored Women". The Black Suffragist. September 11, 2017.

- ^ "National Association of Colored Women's Clubs". Britannica.com.

- ^ "SISTERHOOD: The Black Suffragist: Trailblazers of Social Justice—A Documentary Film". The Black Suffragist.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lichtman, Allan J. (2018). The Embattled Vote in America: From the Founding to the Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780674972360.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weiss, Elaine (2018). The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143128991.

- ^ a b c d "Votes for Women means Votes for Black Women". National Women's History Museum. August 16, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ a b "Carrie Chapman Catt (1859–1947) | Turning Point Suffragist Memorial". Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c Ault, Alicia (April 9, 2019). "How Women Got the Vote Is a Far More Complex Story Than the History Textbooks Reveal". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Evans, Sara M. (1989). Born for Liberty: A History of Women in America. New York: The Free Press. pp. 164–72.

- ^ "How World War I helped give US women the right to vote". army.mil. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Christine Stansell. The Feminist Promise. New York: The Modern Library, 2011, pp. 171–174.

- ^ a b "Nineteenth Amendment | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Lunardini, C.; Knock, T. (1980). "Woodrow Wilson and Woman Suffrage: A New Look". Political Science Quarterly. 95 (4): 655–671. doi:10.2307/2150609. JSTOR 2150609.

- ^ "The House's 1918 Passage of a Constitutional Amendment Granting Women the Right to Vote | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cooney, Robert P. J. Jr. (2005). Winning the Vote: the Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. Santa Cruz, CA: American Graphic Press. pp. 408–427. ISBN 978-0977009503.

- ^ "To Pass HJR 1". govtrack.us. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ Shuler, Marjorie (September 4, 1920). "Out of Subjection Into Freedom". The Woman Citizen: 360. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012.

- ^ Keyssar, Alexander (August 15, 2001). The Right to Vote. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02969-3.

- ^ "Women's Suffrage in Wisconsin". Wisconsin Historical Society. June 5, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Robert B., and Mark E. Byrnes (Fall 2009). "The "Bitterest Fight": The Tennessee General Assembly and the Nineteenth Amendment". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 68 (3): 270–295. JSTOR 42628623.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goodstein, A. (1998). "A Rare Alliance: African American and White Women in the Tennessee Elections of 1919 and 1920". The Journal of Southern History. 64 (2): 219–46. doi:10.2307/2587945. JSTOR 2587945..

- ^ Van West 1998.

- ^ Hakim 1995, pp. 29–33.

- ^ Monroe, Judy (1998). The Nineteenth Amendment: Women's Right to Vote. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Ensloe Publishers, Inc. pp. 77. ISBN 978-0-89490-922-1.

- ^ a b Morris, Mildred (August 19, 1920). "Tennessee Fails to Reconsider Suffrage Vote — Fight for All Rights Still Facing Women". The Washington Times. p. 1. Morris is writer for "Fight for All Rights..." article only.

- ^ a b Mount, Steve (January 2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ "Claim Wisconsin First to O.K. Suffrage". Milwaukee Journal. November 2, 1919. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ^ a b "Two States Ratify Votes for Women". The Ottawa Herald. Ottawa, Kansas. June 10, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Wisconsin O.K.'s Suffrage; Illinois First". The Capital Times. Madison, Wisconsin. June 10, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harper, Ida Husted, ed. (1922). History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 6: 1900–1920. Rochester, New York: J. J. Little & Ives Company for the National Woman Suffrage Association. p. 164. OCLC 963795738.

- ^ "Michigan Third to Put O.K. on Suffrage Act". The Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. June 10, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Suffrage is Ratified". The Independence Daily Reporter. Independence, Kansas. June 16, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Assembly to O. K. Suffrage with Dispatch". The Dayton Daily News. Dayton, Ohio. June 16, 1919. p. 9. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Ohio Legislature Favors Suffrage". The Fremont Daily Messenger. Fremont, Ohio. June 17, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Weatherford 1998, p. 231.

- ^ "Women Suffrage Amendment Wins in Legislature (pt. 1)". The New York Times. New York, New York. June 17, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

and "Women Suffrage Amendment Wins in Legislature (pt. 2)". The New York Times. New York, New York. June 17, 1919. p. 9. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

and "Women Suffrage Amendment Wins in Legislature (pt. 2)". The New York Times. New York, New York. June 17, 1919. p. 9. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weatherford 1998, p. 232.

- ^ "Utah Ratifies the Suffrage Amendment". The Ogden Standard. Ogden, Utah. September 30, 1919. p. 6. Retrieved December 18, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Weatherford 1998, pp. 231–233.

- ^ "House Resolution 5, Enacted 01/07/2020: Joyously Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Rhode Island's Ratification of the 19th Amendment, Granting Women the Right to Vote". House of Representatives of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Conkright, Bessie Taul (January 7, 1920). "Women Hold Jubilee Meet". Lexington Leader. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Morgan, Anita (2019). "'An Act of Tardy Justice': The Story of Women's Suffrage in Indiana". Indiana Women's Suffrage Centennial. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Weatherford 1998, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weatherford 1998, p. 233.

- ^ a b Weatherford 1998, p. 237.

- ^ Weatherford 1998, p. 237-238.

- ^ Weatherford 1998, p. 238.

- ^ Weatherford 1998, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Monroe, Judy. The Nineteenth Amendment: Women's Right to Vote. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Ensloe Publishers, Inc. p. 75.

- ^ Hine, Darlene Clark; Farnham, Christie Anne (1997). "Black Women's Culture of Resistance and the Right to Vote". In Farnham, Christie Anne (ed.). Women of the American South: A Multicultural Reader. New York: NYU Press. pp. 204–219. ISBN 9780814726549.

- ^ "House Beats Suffrage by 62 to 22 Vote". The Portsmouth Star. Portsmouth, Virginia. February 12, 1920. p. 1.

- ^ "The Suffrage Amendment". Lenoir News-Topic. Lenoir, North Carolina. February 12, 1920. p. 2.

- ^ "Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment by the Florida Legislature, 1969". Institute of Museum and Library Services. Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ 258 U.S. 130 (1922)

- ^ a b c d Anzalone 2002, p. 17.

- ^ a b Bronson, Minnie (November 6, 1920). "Maryland League for State Defense Starts Great Suit". The Woman Patriot. Vol. 4, no. 45. p. 2 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Leser v. Garnett page 217" (PDF). Independence Institute. October 1921.

- ^ "258 U.S. 130—Leser v. Garnett". OpenJurist. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Maryland and the 19th Amendment". National Park Service. September 12, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

The court also said that, since the secretaries of state of Tennessee and West Virginia had accepted the ratifications, that they were necessarily valid.

- ^ 258 U.S. 126 (1922)

- ^ Fairchild v. Hughes, 258 U.S. 126 (1922)

- ^ Woloch 1984, p. 354.

- ^ Dumenil 1995, pp. 23–30.

- ^ Lemons, J. Stanley (1969). "The Sheppard-Towner Act: Progressivism in the 1920s". The Journal of American History. 55 (4): 776–786. doi:10.2307/1900152. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 1900152. PMID 19591257.

- ^ Baker 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Harvey, Anna L. (July 13, 1998). Votes Without Leverage: Women in American Electoral Politics, 1920–1970. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780521597432.

- ^ Moses & Hartmann 1995, pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ Harvey, Anna L. (July 13, 1998). Votes Without Leverage: Women in American Electoral Politics, 1920–1970. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10, 210. ISBN 9780521597432.

- ^ "THE GENDER GAP, Voting Choices In Presidential Elections; Fact Sheet" (PDF). Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP), Eagleton Institute of Politics, Rutgers University. 2017.

- ^ "Was women's suffrage a failure? What new evidence tells us about the first women voters". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Counting Women's Ballots". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "19th Amendment: How far have women in politics come since 1920?". The Christian Science Monitor. August 18, 2010. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c Nelson, Marjory (1979). "women suffrage and race". Off Our Backs. 9 (10): 6–22. ISSN 0030-0071. JSTOR 25793145.

- ^ "African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Paul, Alice (February 16, 1921). "The White Woman's Burden". The Nation. 112 (2902): 257.

- ^ a b Salvatore, Susan Cianci (June 7, 2019). "Civil Rights in America: Racial Voting Rights" (PDF). National Park Service.

- ^ Staples, Brent (July 28, 2018). "How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women". Opinion. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Contreras, Russell (November 1, 2018). "How the Native American Vote Evolved". Great Falls Tribune. Great Falls, Montana. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Sherri. "Women's Equality Day celebrates the 19th Amendment. For nonwhite women, the fight to vote continued for decades". The Lily. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "On this day, all Indians made United States citizens". National Constitution Center—constitutioncenter.org. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Oxford, Andrew (August 2, 2018). "It's been 70 years since court ruled Native Americans could vote in New Mexico". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ "Puerto Rico and the 19th Amendment". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ McCammon, H.; Chaudhuri, S.; Hewitt, L.; Muse, C.; Newman, H.; Smith, C.; Terrell, T. (2008). "Becoming Full Citizens: The U.S. Women's Jury Rights Campaigns, the Pace of Reform, and Strategic Adaptation". American Journal of Sociology. 113 (4): 1104–1147. doi:10.1086/522805. S2CID 58919399.

- ^ Brown, J. (1993). "The Nineteenth Amendment and Women's Equality". The Yale Law Journal. 102 (8): 2175–2204. doi:10.2307/796863. JSTOR 796863.

- ^ "Current Numbers". CAWP. June 12, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Rohlinger, Deana (December 13, 2018). "In 2019, women's rights are still not explicitly recognized in US Constitution". The Conversation. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Henning, Arthur Sears (September 26, 1921). "WOMAN'S PARTY ALL READY FOR EQUALITY FIGHT; Removal Of All National and State Discriminations Is Aim. SENATE AND HOUSE TO GET AMENDMENT; A Proposed Constitutional Change To Be Introduced On October 1". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1.

- ^ "The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues". EveryCRSReport.com. July 18, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Cott, Nancy (1984). "Feminist Politics in the 1920s: The National Woman's Party". Journal of American History. 71 (1): 43–68. doi:10.2307/1899833. JSTOR 1899833.

- ^ Dollinger, Genora Johnson (1997). "Women and Labor Militancy". In Ware, Susan (ed.). Modern American Women: A Documentary History. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-07-071527-0.

- ^ "Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment". cdlib.org. Suffragists Oral History Project.

- ^ Harrison, Cynthia Ellen (1989). On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945–1968. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520909304.

- ^ a b Rick Pearson; Bill Lukitsch (May 31, 2018). "Illinois approves Equal Rights Amendment, 36 years after deadline". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Bid to revive Equal Rights Amendment in Virginia fails by 1 vote". WHSV. February 21, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Gross, Samantha J. (August 26, 2019). "99 years ago Florida led in women's suffrage. Are equal rights still a priority?". Miami Herald. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c Goolsby, Denise (September 19, 2016). "No room for fourth bust on suffragist statue?". Desert Sun.

- ^ "The Portrait Monument". Atlas Obscura.

- ^ Boissoneault, Lorraine (May 13, 2017). "The Suffragist Statue Trapped in a Broom Closet for 75 Years: The Portrait Monument was a testament to women's struggle for the vote that remained hidden till 1997". Smithsonian.com.

- ^ Bliss, Jessica (August 26, 2016). "Alan LeQuire's Women Suffrage Monument unveiled in Nashville's Centennial Park". The Tennessean. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ "Too Few Statues of Women". Tennessee Suffrage Monument, Inc.

- ^ Randal Rust. "Woman Suffrage Movement". Tennessee Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Listen to your Mother: a Mom-ument". RoadsideAmerica.com.

- ^ Burt, Spencer (October 3, 2018). "New Utah license plates celebrating Utah women's suffrage now available". Deseretnews.com.

- ^ "Women's Equality Day". National Women's History Museum. August 26, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Women's Equality Day | American holiday". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Schuessler, Jennifer (August 15, 2019). "The Complex History of the Women's Suffrage Movement". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ Jackson, David; Collins, Michael (August 18, 2020). "Trump honors 100th anniversary of 19th Amendment by announcing pardon for Susan B. Anthony". USA Today. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ^ Litman, Kevin (April 25, 2018). "Bob Dorough: 9 Best 'Schoolhouse Rock!' Songs from the Composer". Inverse. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "Schoolhouse Rock—Sufferin' 'til Suffrage". Schoolhouserock.tv. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "27: The Most Perfect Album | Radiolab". WNYC Studios. September 19, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "Dolly Parton Hopes to "Uplift Women" in New Song That Highlights 19th Amendment: Women's Right to Vote [Listen]". Nash Country Daily. September 18, 2018. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ "SECONDARY SOURCE—One Woman, One Vote: A PBS Documentary". Women's Suffrage and the Media. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Leab, Amber (November 4, 2008). "'One Woman, One Vote': A Documentary Review". Bitch Flicks.

- ^ Burns, Ken. "Not For Ourselves Alone". PBS.

- ^ "Not for Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony". IMDb. November 7, 1999.

- ^ Green, John. "Women's Suffrage: Crash Course US History #31". CrashCourse on YouTube. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021.

- ^ "Women in the 19th Century". IMDb. May 23, 2013.

- ^ McNeil-Walsh, Gemma (February 6, 2018). "Suffrage On Screen: Five Vital Films About How Women Won the Vote". Rights Info: Human Rights News, Views & Info. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Iron Jawed Angels". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Nevins, Jake (August 1, 2018). "Hillary Clinton and Steven Spielberg to make TV series on women's suffrage". The Guardian.

- ^ Shoot, Brittany (August 1, 2018). "Hillary Clinton Is Producing a Television Series on Women's Fight to Win Voting Rights". Fortune.

Bibliography

- Amar, Akhil Reed (2005). America's Constitution: A Biography. Random House trade pbk. ed. ISBN 978-0-8129-7272-6.

- Anzalone, Christopher A (2002). Supreme Court Cases on Gender and Sexual Equality, 1787–2001. United States Supreme Court (Sharpe). ISBN 978-0-7656-0683-9.

- Baker, Jean H. (2009). Women and the U.S. Constitution, 1776–1920. New Essays in American Constitutional History. Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association. ISBN 9780872291638.

- Banaszak, Lee A. (1996). Why Movements Succeed or Fail: Opportunity, Culture, and the Struggle for Woman Suffrage. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2207-2.

- DuBois, Ellen Carol, et al. "Interchange: Women's Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote". Journal of American History 106.3 (2019): 662–694.

- Dumenil, Lynn (1995). The Modern Temper: American Culture and Society in the 1920s. Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-6978-1.

- Gidlow, Liette. "The Sequel: The Fifteenth Amendment, the Nineteenth Amendment, and Southern Black Women's Struggle to Vote". Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17.3 (2018): 433–449.

- Hakim, Joy (1995). "Book 9: War, Peace, and All That Jazz". A History of US. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509514-2.

- Hasen, Richard L., and Leah Litman. "Thin and Thick Conceptions of the Nineteenth Amendment Right to Vote and Congress's Power to Enforce It". Georgetown Law Journal (2020): 2019–63. online

- McCammon, Holly J., and Lee Ann Banaszak, eds. 100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment: An Appraisal of Women's Political Activism (Oxford UP, 2018).

- Mead, Rebecca J. (2004). How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5676-8.

- Monopoli, Paula A. (2020). Constitutional Orphan: Gender Equality and the Nineteenth Amendment. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-09280-1.

- Moses, Claire Goldberg; Hartmann, Heidi I. (1995). U.S. Women in Struggle: A Feminist Studies Anthology. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02166-4.

- Teele, Dawn Langan. Forging the Franchise: The Political Origins of the Women's Vote (2018) Online review

- Van West, Carroll, ed. (1998). "Woman Suffrage Movement". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 1558535993. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- Weatherford, Doris (1998). A History of the American Suffragist Movement. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070659.

- Woloch, Nancy (1984). Women and the American Experience. New York: Knopf. ISBN 9780394535159.

External links

- 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution from the Library of Congress

- Our Documents: Nineteenth Amendment

- CRS Annotated Constitution: Nineteenth Amendment

- Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment from the National Archives