| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The Roaring Twenties, sometimes stylized as Roaring '20s, refers to the 1920s decade in music and fashion, as it happened in Western society and Western culture. It was a period of economic prosperity with a distinctive cultural edge in the United States and Europe, particularly in major cities such as Berlin,[1] Buenos Aires,[2][3] Chicago,[4] London,[5] Los Angeles,[6] Mexico City,[3] New York City,[7] Paris,[8] and Sydney.[9] In France, the decade was known as the années folles ('crazy years'),[10] emphasizing the era's social, artistic and cultural dynamism. Jazz blossomed, the flapper redefined the modern look for British and American women,[11][12] and Art Deco peaked.[13]

The social and cultural features known as the Roaring Twenties began in leading metropolitan centers and spread widely in the aftermath of World War I. The spirit of the Roaring Twenties was marked by a general feeling of novelty associated with modernity and a break with tradition, through modern technology such as automobiles, moving pictures, and radio, bringing "modernity" to a large part of the population. Formal decorative frills were shed in favor of practicality in both daily life and architecture. At the same time, jazz and dancing rose in popularity, in opposition to the mood of World War I. As such, the period often is referred to as the Jazz Age.

The 1920s saw the large-scale development and use of automobiles, telephones, films, radio, and electrical appliances in the lives of millions in the Western world. Aviation soon became a business due to its rapid growth. Nations saw rapid industrial and economic growth, accelerated consumer demand, and introduced significant new trends in lifestyle and culture. The media, funded by the new industry of mass-market advertising driving consumer demand, focused on celebrities, especially sports heroes and movie stars, as cities rooted for their home teams and filled the new palatial cinemas and gigantic sports stadiums. In many countries, women won the right to vote.

Wall Street invested heavily in Germany under the 1924 Dawes Plan, named after banker and later 30th Vice President Charles G. Dawes. The money was used indirectly to pay reparations to countries that also had to pay off their war debts to Washington.[14] While by the middle of the decade prosperity was widespread, with the second half of the decade known, especially in Germany, as the "Golden Twenties",[15] the decade was coming fast to an end. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 ended the era, as the Great Depression brought years of hardship worldwide.[16]

Economy

The Roaring Twenties was a decade of economic growth and widespread prosperity, driven by recovery from wartime devastation and deferred spending, a boom in construction, and the rapid growth of consumer goods such as automobiles and electricity in North America and Europe and a few other developed countries such as Australia.[18] The economy of the United States, successfully transitioned from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy, boomed and provided loans for a European boom as well. Some sectors stagnated, especially farming and coal mining. The US became the richest country in the world per capita and since the late-19th century had been the largest in total GDP. Its industry was based on mass production, and its society acculturated into consumerism. European economies, by contrast, had a more difficult post-war readjustment and did not begin to flourish until about 1924.[19]

At first, the end of wartime production caused a brief but deep recession, the post–World War I recession of 1919–1920 and a sharp deflationary recession or depression in 1920–1921. Quickly, however, the economies of the U.S. and Canada rebounded as returning soldiers re-entered the labor force and munitions factories were retooled to produce consumer goods.

New products and technologies

Mass production made technology affordable to the middle class.[19] The automotive industry, the film industry, the radio industry, and the chemical industry took off during the 1920s.

Automobiles

Before World War I, cars were a luxury good. In the 1920s, mass-produced vehicles became commonplace in the U.S. and Canada. By 1927, the Ford Motor Company discontinued the Ford Model T after selling 15 million units of that model. It had been in continuous production from October 1908 to May 1927.[20][21] The company planned to replace the old model with a newer one, the Ford Model A.[22] The decision was a reaction to competition. Due to the commercial success of the Model T, Ford had dominated the automotive market from the mid-1910s to the early-1920s. In the mid-1920s, Ford's dominance eroded as its competitors had caught up with Ford's mass production system. They began to surpass Ford in some areas, offering models with more powerful engines, new convenience features, and styling.[23][24][25]

Only about 300,000 vehicles were registered in 1918 in all of Canada, but by 1929, there were 1.9 million. By 1929, the United States had just under 27,000,000[26] motor vehicles registered. Automobile parts were being manufactured in Ontario, near Detroit, Michigan. The automotive industry's influence on other segments of the economy were widespread, jump starting industries such as steel production, highway building, motels, service stations, car dealerships, and new housing outside the urban core.

Ford opened factories around the world and proved a strong competitor in most markets for its low-cost, easy-maintenance vehicles. General Motors, to a lesser degree, followed. European competitors avoided the low-price market and concentrated on more expensive vehicles for upscale consumers.[27]

Radio

Radio became the first mass broadcasting medium. Radios were expensive, but their mode of entertainment proved revolutionary. Radio advertising became a platform for mass marketing. Its economic importance led to the mass culture that has dominated society since this period. During the "Golden Age of Radio", radio programming was as varied as the television programming of the 21st century. The 1927 establishment of the Federal Radio Commission introduced a new era of regulation.

In 1925, electrical recording, one of the greater advances in sound recording, became available with commercially issued gramophone records.

Cinema

The cinema boomed, producing a new form of entertainment that virtually ended the old vaudeville theatrical genre. Watching a film was cheap and accessible; crowds surged into new downtown movie palaces and neighborhood theaters. Since the early 1910s, lower-priced cinema successfully competed with vaudeville. Many vaudeville performers and other theatrical personalities were recruited by the film industry, lured by greater salaries and less arduous working conditions. The introduction of sound film, a.k.a. "the talkies" which did not surge until the end of the decade of the 1920s, eliminated vaudeville's last major advantage and put it into sharp financial decline. The prestigious Orpheum Circuit, a chain of vaudeville and movie theaters, was absorbed by a new film studio.[28]

Sound movies

In 1923, inventor Lee de Forest at Phonofilm released a number of short films with sound. Meanwhile, inventor Theodore Case developed the Movietone sound system and sold the rights to the film studio, Fox Film. In 1926, the Vitaphone sound system was introduced. The feature film Don Juan (1926) was the first feature-length film to use the Vitaphone sound system with a synchronized musical score and sound effects, though it had no spoken dialogue.[29] The film was released by the film studio Warner Bros. In October 1927, the sound film The Jazz Singer (1927) turned out to be a smash box-office success. It was innovative for its use of sound. Produced with the Vitaphone system, most of the film does not contain live-recorded audio, relying on a score and effects. When the movie's star, Al Jolson, sings, however, the film shifts to sound recorded on the set, including both his musical performances and two scenes with ad-libbed speech—one of Jolson's character, Jakie Rabinowitz (Jack Robin), addressing a cabaret audience; the other an exchange between him and his mother. The "natural" sounds of the settings were also audible.[30] The film's profits were proof enough to the film industry that the technology was worth investing in.[31]

In 1928, the film studios Famous Players–Lasky (later known as Paramount Pictures), First National Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Universal Studios signed an agreement with Electrical Research Products Inc. (ERPI) for the conversion of production facilities and theaters for sound film. Initially, all ERPI-wired theaters were made Vitaphone-compatible; most were equipped to project Movietone reels as well.[32] Also in 1928, Radio Corporation of America (RCA) marketed a new sound system, the RCA Photophone system. RCA offered the rights to its system to the subsidiary RKO Pictures. Warner Bros. continued releasing a few films with live dialogue, though only in a few scenes. It finally released Lights of New York (1928), the first all-talking full-length feature film. The animated short film Dinner Time (1928) by the Van Beuren Studios was among the first animated sound films. It was followed a few months later by the animated short film Steamboat Willie (1928), the first sound film by the Walt Disney Animation Studios. It was the first commercially successful animated short film and introduced the character Mickey Mouse.[33]Steamboat Willie was the first cartoon to feature a fully post-produced soundtrack, which distinguished it from earlier sound cartoons. It became the most popular cartoon of its day.[34]

For much of 1928, Warner Bros. was the only studio to release talking features. It profited from its innovative films at the box office. Other studios quickened the pace of their conversion to the new technology and started producing their own sound films and talking films. In February 1929, sixteen months after The Jazz Singer, Columbia Pictures became the eighth and last major studio to release a talking feature. In May 1929, Warner Bros. released On with the Show! (1929), the first all-color, all-talking feature film.[35] Soon silent film production ceased. The last totally silent feature produced in the US for general distribution was The Poor Millionaire, released by Biltmore Pictures in April 1930. Four other silent features, all low-budget Westerns, were also released in early 1930.[36]

Aviation

The 1920s saw milestones in aviation that seized the world's attention. In 1927, Charles Lindbergh rose to fame with the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight. He took off from Roosevelt Field in New York and landed at Paris–Le Bourget Airport. It took Lindbergh 33.5 hours to cross the Atlantic Ocean.[37] His aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, was a custom-built, single engine, single-seat monoplane. It was designed by aeronautical engineer Donald A. Hall. In Britain, Amy Johnson (1903–1941) was the first woman to fly alone from Britain to Australia. Flying solo or with her husband, Jim Mollison, she set numerous long-distance records during the 1930s.[38]

Television

The 1920s saw several inventors advance work on television, but programs did not reach the public until the eve of World War II, and few people saw any television before the mid 1940s.

In July 1928, John Logie Baird demonstrated the world's first color transmission, using scanning discs at the transmitting and receiving ends with three spirals of apertures, each spiral with a filter of a different primary color; and three light sources at the receiving end, with a commutator to alternate their illumination.[39] That same year he also demonstrated stereoscopic television.[40]

In 1927, Baird transmitted a long-distance television signal over 438 miles (705 km) of telephone line between London and Glasgow; Baird transmitted the world's first long-distance television pictures to the Central Hotel at Glasgow Central Station.[41] Baird then set up the Baird Television Development Company Ltd and in 1928 made the first transatlantic television transmission, from London to Hartsdale, New York and the first television programme for the BBC.[42]

Medicine

For decades biologists had been at work on the medicine that became penicillin. In 1928, Scottish biologist Alexander Fleming discovered a substance that killed a number of disease-causing bacteria. In 1929, he named the new substance penicillin. His publications were largely ignored at first, but it became a significant antibiotic in the 1930s. In 1930, Cecil George Paine, a pathologist at Sheffield Royal Infirmary, used penicillin to treat sycosis barbae, eruptions in beard follicles, but was unsuccessful. Moving to ophthalmia neonatorum, a gonococcal infection in infants, he achieved the first recorded cure with penicillin, on November 25, 1930. He then cured four additional patients (one adult and three infants) of eye infections, but failed to cure a fifth.[43][44][45]

New infrastructure

The automobile's dominance led to a new psychology celebrating mobility.[46] Cars and trucks needed road construction, new bridges, and regular highway maintenance, largely funded by local and state government through taxes on gasoline. Farmers were early adopters as they used their pickups to haul people, supplies and animals. New industries were spun off—to make tires and glass and refine fuel, and to service and repair cars and trucks by the millions. New car dealers were franchised by the car makers and became prime movers in the local business community. Tourism gained an enormous boost, with hotels, restaurants and curio shops proliferating.[47][48]

Electrification, having slowed during the war, progressed greatly as more of the US and Canada was added to the electrical grid. Industries switched from coal power to electricity. At the same time, new power plants were constructed. In America, electricity production almost quadrupled.[49]

Telephone lines also were being strung across the continent. Indoor plumbing was installed for the first time in many homes, made possible due to modern sewer systems.

Urbanization reached a milestone in the 1920 census, the results of which showed that slightly more Americans lived in urban areas, towns, and cities, populated by 2,500 or more people, than in small towns or rural areas. However, the nation was fascinated with its great metropolitan centers that contained about 15% of the population. The cities of New York and Chicago vied in building skyscrapers, and New York pulled ahead with its Empire State Building. The basic pattern of the modern white-collar job was set during the late-19th century, but it now became the norm for life in large and medium-sized cities. Typewriters, filing cabinets, and telephones, brought many unmarried women into clerical jobs. In Canada, by the end of the decade, one in five workers were women. Interest in finding jobs, in the now ever-growing manufacturing sector of U.S. cities, became widespread among rural Americans.[50]

Society

Suffrage

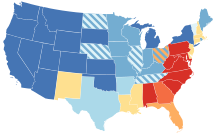

Many countries expanded women's voting rights, such as the United States, Canada, Great Britain, India, and various European countries in 1917–1921. This influenced many governments and elections by increasing the number of voters (but not doubling it, because many women did not vote during the early years of suffrage, as can be seen by the large drop in voter turnout). Politicians responded by focusing more on issues of concern to women, especially peace, public health, education, and the status of children. On the whole, women voted much like men, except they were more interested in peace,[51][52][53] even when it meant appeasement.[54]

Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was composed of young people who came out of World War I disillusioned and cynical about the world. The term usually refers specifically to American literary notables who lived in Paris at the time. Famous members included Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein who wrote novels and short stories criticizing the materialism they perceived to be rampant during this era.

In the United Kingdom, the bright young things were young aristocrats and socialites who threw fancy dress parties, went on elaborate treasure hunts, were seen in all the trendy venues, and were well covered by the gossip columns of the London tabloids.[55]

Social criticism

As the average American in the 1920s became more enamored of wealth and everyday luxuries, some began satirizing the hypocrisy and greed they observed. Of these social critics, Sinclair Lewis was the most popular. His popular 1920 novel Main Street satirized the dull and ignorant lives of the residents of a Midwestern town. He followed with Babbitt, about a middle-aged businessman who rebels against his dull life and family, only to realize that the younger generation is as hypocritical as his own. Lewis satirized religion with Elmer Gantry, which followed a con man who teams with an evangelist to sell religion to a small town.

Other social critics included Sherwood Anderson, Edith Wharton, and H. L. Mencken. Anderson published a collection of short stories titled Winesburg, Ohio, which studied the dynamics of a small town. Wharton mocked the fads of the new era through her novels, such as Twilight Sleep (1927). Mencken criticized narrow American tastes and culture in essays and articles.

Art Deco

Art Deco was the style of design and architecture that marked the era. Originating in Europe, it spread to the rest of western Europe and North America towards the mid-1920s.

In the U.S., one of the more remarkable buildings featuring this style was constructed as the tallest building of the time: the Chrysler Building. The forms of Art Deco were pure and geometric, though the artists often drew inspiration from nature. In the beginning, lines were curved, though rectilinear designs would later become more and more popular.

Expressionism and surrealism

Painting in North America during the 1920s developed in a different direction from that of Europe. In Europe, the 1920s were the era of expressionism and later surrealism. As Man Ray stated in 1920 after the publication of a unique issue of New York Dada: "Dada cannot live in New York".

Cinema

At the beginning of the decade, films were silent and colorless. In 1922, the first all-color feature, The Toll of the Sea, was released. In 1926, Warner Bros. released Don Juan, the first feature with sound effects and music. In 1927, Warner released The Jazz Singer, the first sound feature to include limited talking sequences.

The public went wild for sound films, and movie studios converted to sound almost overnight.[56] In 1928, Warner released Lights of New York, the first all-talking feature film. In the same year, the first sound cartoon, Dinner Time, was released. Warner ended the decade by unveiling On with the Show in 1929, the first all-color, all-talking feature film.

Cartoon shorts were popular in movie theaters during this time. In the late 1920s, Walt Disney emerged. Mickey Mouse made his debut in Steamboat Willie on November 18, 1928, at the Colony Theater in New York City. Mickey was featured in more than 120 cartoon shorts, the Mickey Mouse Club, and other specials. This started Disney and led to creation of other characters going into the 1930s.[57] Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a character created by Disney before Mickey in 1927, was contracted by Universal for distribution purposes, and starred in a series of shorts between 1927 and 1928. Disney lost the rights to the character, but in 2006, regained the rights to Oswald. He was the first Disney character to be merchandised.[58]

The period had the emergence of box-office draws such as Mae Murray, Ramón Novarro, Rudolph Valentino, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Warner Baxter, Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, Baby Peggy, Bebe Daniels, Billie Dove, Dorothy Mackaill, Mary Astor, Nancy Carroll, Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, William Haines, Conrad Nagel, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, Dolores del Río, Norma Talmadge, Colleen Moore, Nita Naldi, Leatrice Joy, John Barrymore, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Anna May Wong, and Al Jolson.[59]

Harlem

African American literary and artistic culture developed rapidly during the 1920s under the banner of the "Harlem Renaissance". In 1921, the Black Swan Corporation was founded. At its height, it issued 10 recordings per month. All-African American musicals also started in 1921. In 1923, the Harlem Renaissance Basketball Club was founded by Bob Douglas. During the late-1920s, and especially in the 1930s, the basketball team became known as the best in the world.

The first issue of Opportunity was published. The African American playwright Willis Richardson debuted his play The Chip Woman's Fortune at the Frazee Theatre (also known as the Wallacks theatre).[1] Notable African American authors such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston began to achieve a level of national public recognition during the 1920s.

Jazz Age

The 1920s brought new styles of music into the mainstream of culture in avant-garde cities. Jazz became the most popular form of music for youth.[60] Historian Kathy J. Ogren wrote that, by the 1920s, jazz had become the "dominant influence on America's popular music generally" [61] Scott DeVeaux argues that a standard history of jazz has emerged such that: "After an obligatory nod to African origins and ragtime antecedents, the music is shown to move through a succession of styles or periods: New Orleans jazz up through the 1920s, swing in the 1930s, bebop in the 1940s, cool jazz and hard bop in the 1950s, free jazz and fusion in the 1960s.... There is substantial agreement on the defining features of each style, the pantheon of great innovators, and the canon of recorded masterpieces."[62]

The pantheon of performers and singers from the 1920s include Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, Joe "King" Oliver, James P. Johnson, Fletcher Henderson, Frankie Trumbauer, Paul Whiteman, Roger Wolfe Kahn, Bix Beiderbecke, Adelaide Hall, and Bing Crosby. The development of urban and city blues also began in the 1920s with performers such as Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. In the latter part of the decade, early forms of country music were pioneered by Jimmie Rodgers, The Carter Family, Uncle Dave Macon, Vernon Dalhart, and Charlie Poole.[63]

Dance

Dance clubs became enormously popular in the 1920s. Their popularity peaked in the late 1920s and reached into the early 1930s. Dance music came to dominate all forms of popular music by the late 1920s. Classical pieces, operettas, folk music, etc., were all transformed into popular dancing melodies to satiate the public craze for dancing. For example, many of the songs from the 1929 Technicolor musical operetta "The Rogue Song" (starring the Metropolitan Opera star Lawrence Tibbett) were rearranged and released as dancing music and became popular dance club hits in 1929.

Dance clubs across the U.S.-sponsored dancing contests, where dancers invented, tried and competed with new moves. Professionals began to hone their skills in tap dance and other dances of the era throughout the stage circuit across the United States. With the advent of talking pictures (sound film), musicals became all the rage and film studios flooded the box office with extravagant and lavish musical films. The representative was the musical Gold Diggers of Broadway, which became the highest-grossing film of the decade. Harlem played a key role in the development of dance styles. Several entertainment venues attracted people of all races. The Cotton Club featured black performers and catered to a white clientele, while the Savoy Ballroom catered to a mostly black clientele. Some religious moralists preached against "Satan in the dance hall" but had little impact.[64]

The most popular dances throughout the decade were the foxtrot, waltz, and American tango. From the early 1920s, however, a variety of eccentric novelty dances were developed. The first of these were the Breakaway and Charleston. Both were based on African American musical styles and beats, including the widely popular blues. The Charleston's popularity exploded after its feature in two 1922 Broadway shows. A brief Black Bottom craze, originating from the Apollo Theater, swept dance halls from 1926 to 1927, replacing the Charleston in popularity.[65] By 1927, the Lindy Hop, a dance based on Breakaway and Charleston and integrating elements of tap, became the dominant social dance. Developed in the Savoy Ballroom, it was set to stride piano ragtime jazz. The Lindy Hop later evolved into other Swing dances.[66] These dances, nonetheless, never became mainstream, and the overwhelming majority of people in Western Europe and the U.S. continued to dance the foxtrot, waltz, and tango throughout the decade.[67]

The dance craze had a large influence on popular music. Large numbers of recordings labeled as foxtrot, tango, and waltz were produced and gave rise to a generation of performers who became famous as recording artists or radio artists. Top vocalists included Nick Lucas, Adelaide Hall, Scrappy Lambert, Frank Munn, Lewis James, Chester Gaylord, Gene Austin, James Melton, Franklyn Baur, Johnny Marvin, Annette Hanshaw, Helen Kane, Vaughn De Leath, and Ruth Etting. Leading dance orchestra leaders included Bob Haring, Harry Horlick, Louis Katzman, Leo Reisman, Victor Arden, Phil Ohman, George Olsen, Ted Lewis, Abe Lyman, Ben Selvin, Nat Shilkret, Fred Waring, and Paul Whiteman.[68]

Fashion

Attire

Paris set the fashion trends for Europe and North America.[69] The fashion for women was all about getting loose. Women wore dresses all day, every day. Day dresses had a drop waist, which was a sash or belt around the low waist or hip and a skirt that hung anywhere from the ankle on up to the knee, never above. Daywear had sleeves (long to mid-bicep) and a skirt that was straight, pleated, hank hem, or tired. Jewelry was less conspicuous.[70] Hair was often bobbed, giving a boyish look.[71]

For men in white collar jobs, business suits were the day to day attire. Striped, plaid, or windowpane suits came in dark gray, blue, and brown in the winter and ivory, white, tan, and pastels in the summer. Shirts were white and neckties were essential.[72]

Immortalized in movies and magazine covers, young women's fashions of the 1920s set both a trend and social statement, a breaking-off from the rigid Victorian way of life. These young, rebellious, middle-class women, labeled 'flappers' by older generations, did away with the corset and donned slinky knee-length dresses, which exposed their legs and arms. The hairstyle of the decade was a chin-length bob, which had several popular variations. Cosmetics, which until the 1920s were not typically accepted in American society because of their association with prostitution, became extremely popular.[73]

In the 1920s, new magazines appealed to young German women with a sensuous image and advertisements for the appropriate clothes and accessories they would want to purchase. The glossy pages of Die Dame and Das Blatt der Hausfrau displayed the "Neue Frauen", "New Girl" – what Americans called the flapper. She was young and fashionable, financially independent, and was an eager consumer of the latest fashions. The magazines kept her up to date on styles, clothes, designers, arts, sports, and modern technology such as automobiles and telephones.[74]

Sexuality of women during the 1920s

The 1920s was a period of social revolution, coming out of World War I, society changed as inhibitions faded and youth demanded new experiences and more freedom from old controls. Chaperones faded in importance as "anything goes" became a slogan for youth taking control of their subculture.[75] A new woman was born—a "flapper" who danced, drank, smoked and voted. This new woman cut her hair, wore make-up, and partied. She was known for being giddy and taking risks.[76] Women gained the right to vote in most countries. New careers opened for single women in offices and schools, with salaries that helped them to be more independent.[77] With their desire for freedom and independence came change in fashion.[78] One of the more dramatic post-war changes in fashion was the woman's silhouette; the dress length went from floor length to ankle and knee length, becoming more bold and seductive. The new dress code emphasized youth: Corsets were left behind and clothing was looser, with more natural lines. The hourglass figure was not popular anymore, and a slimmer, boyish body type was considered appealing. The flappers were known for this and for their high spirits, flirtation, and recklessness when it came to the search for fun and thrills.[79]

Coco Chanel was one of the more enigmatic fashion figures of the 1920s. She was recognized for her avant-garde designs; her clothing was a mixture of wearable, comfortable, and elegant. She was the one to introduce a different aesthetic into fashion, especially a different sense for what was feminine, and based her design on new ethics; she designed for an active woman, one that could feel at ease in her dress.[80] Chanel's primary goal was to empower freedom. She was the pioneer for women wearing pants and for the little black dress, which were signs of a more independent lifestyle.

Changing role of women

Dark blue = full women's suffrage

Bright red = no women's suffrage

Most British historians depict the 1920s as an era of domesticity for women with little feminist progress, apart from full suffrage which came in 1928.[81] On the contrary, argues Alison Light, literary sources reveal that many British women enjoyed:

... the buoyant sense of excitement and release which animates so many of the more broadly cultural activities which different groups of women enjoyed in this period. What new kinds of social and personal opportunity, for example, were offered by the changing cultures of sport and entertainment ... by new patterns of domestic life ... new forms of a household appliance, new attitudes to housework?[82]

With the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, that gave women the right to vote, American feminists attained the political equality they had been waiting for. A generational gap began to form between the "new" women of the 1920s and the previous generation. Prior to the 19th Amendment, feminists commonly thought women could not pursue both a career and a family successfully, believing one would inherently inhibit the development of the other. This mentality began to change in the 1920s, as more women began to desire not only successful careers of their own, but also families.[83] The "new" woman was less invested in social service than the progressive generations, and in tune with the consumerist spirit of the era, she was eager to compete and to find personal fulfillment.[84] Higher education was rapidly expanding for women. Linda Eisenmann claims, "New collegiate opportunities for women profoundly redefined womanhood by challenging the Victorian belief that men's and women's social roles were rooted in biology."[85]

Advertising agencies exploited the new status of women, for example in publishing automobile ads in women's magazines, at a time when the vast majority of purchasers and drivers were men. The new ads promoted new freedoms for affluent women while also suggesting the outer limits of the new freedoms. Automobiles were more than practical devices. They were also highly visible symbols of affluence, mobility, and modernity. The advertisements, wrote Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, "offered women a visual vocabulary to imagine their new social and political roles as citizens and to play an active role in shaping their identity as modern women".[86]

Significant changes in the lives of working women occurred in the 1920s. World War I had temporarily allowed women to enter into industries such as chemical, automobile, and iron and steel manufacturing, which were once deemed inappropriate work for women.[87] Black women, who had been historically closed out of factory jobs, began to find a place in industry during World War I by accepting lower wages and replacing the lost immigrant labor and in heavy work. Yet, like other women during World War I, their success was only temporary; most black women were also pushed out of their factory jobs after the war. In 1920, 75% of the black female labor force consisted of agricultural laborers, domestic servants, and laundry workers.[88]

Legislation passed at the beginning of the 20th century mandated a minimum wage and forced many factories to shorten their workdays. This shifted the focus in the 1920s to job performance to meet demand. Factories encouraged workers to produce more quickly and efficiently with speedups and bonus systems, increasing the pressure on factory workers. Despite the strain on women in the factories, the booming economy of the 1920s meant more opportunities even for the lower classes. Many young girls from working-class backgrounds did not need to help support their families as prior generations did and were often encouraged to seek work or receive vocational training which would result in social mobility.[89]

The achievement of suffrage led to feminists refocusing their efforts towards other goals. Groups such as the National Women's Party continued the political fight, proposing the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 and working to remove laws that used sex to discriminate against women,[90] but many women shifted their focus from politics to challenge traditional definitions of womanhood.

Young women, especially, began staking claim to their own bodies and took part in a sexual liberation of their generation. Many of the ideas that fueled this change in sexual thought were already floating around New York intellectual circles prior to World War I, with the writings of Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis, and Ellen Key. There, thinkers claimed that sex was not only central to the human experience, but also that women were sexual beings with human impulses and desires, and restraining these impulses was self-destructive. By the 1920s, these ideas had permeated the mainstream.[91]

In the 1920s, the co-ed emerged, as women began attending large state colleges and universities. Women entered into the mainstream middle class experience but took on a gendered role within society. Women typically took classes such as home economics, "Husband and Wife", "Motherhood" and "The Family as an Economic Unit". In an increasingly conservative postwar era, a young woman commonly would attend college with the intention of finding a suitable husband. Fueled by ideas of sexual liberation, dating underwent major changes on college campuses. With the advent of the automobile, courtship occurred in a much more private setting. "Petting", sexual relations without intercourse, became the social norm for a portion of college students.[92]

Despite women's increased knowledge of pleasure and sex, the decade of unfettered capitalism that was the 1920s gave birth to the "feminine mystique". With this formulation, all women wanted to marry, all good women stayed at home with their children, cooking and cleaning, and the best women did the aforementioned and in addition, exercised their purchasing power freely and as frequently as possible to better their families and their homes.[93]

Liberalism in Europe

The Allied victory in World War I seems to mark the triumph of liberalism, not just in the Allied countries themselves, but also in Germany and in the new states of Eastern Europe, as well as Japan. Authoritarian militarism as typified by Germany had been defeated and discredited. Historian Martin Blinkhorn argues that the liberal themes were ascendant in terms of "cultural pluralism, religious and ethnic toleration, national self-determination, free-market economics, representative and responsible government, free trade, unionism, and the peaceful settlement of international disputes through a new body, the League of Nations".[94] However, as early as 1917, the emerging liberal order was being challenged by the new communist movement taking inspiration from the Russian Revolution. Communist revolts were beaten back everywhere else, but they did succeed in Russia.[95]

Homosexuality

Homosexuality became much more visible and somewhat more acceptable. London, New York, Paris, Rome,[96] and Berlin were important centers of the new ethic.[97] Historian Jason Crouthamel argues that in Germany, the First World War promoted homosexual emancipation because it provided an ideal of comradeship which redefined homosexuality and masculinity. The many gay rights groups in Weimar Germany favored a militarised rhetoric with a vision of a spiritually and politically emancipated hypermasculine gay man who fought to legitimize "friendship" and secure civil rights.[98] Ramsey explores several variations. On the left, the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee; WhK) reasserted the traditional view that homosexuals were an effeminate "third sex" whose sexual ambiguity and nonconformity was biologically determined. The radical nationalist Gemeinschaft der Eigenen (Community of the Self-Owned) proudly proclaimed homosexuality as heir to the manly German and classical Greek traditions of homoerotic male bonding, which enhanced the arts and glorified relationships with young men. The politically centrist Bund für Menschenrecht (League for Human Rights) engaged in a struggle for human rights, advising gays to live in accordance with the mores of middle-class German respectability.[99]

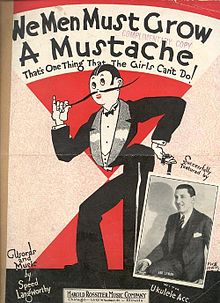

Humor was used to assist in acceptability. One popular American song, "Masculine Women, Feminine Men",[100] was released in 1926 and recorded by numerous artists of the day; it included these lyrics:[101]

Masculine women, Feminine men

Which is the rooster, which is the hen?

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! And, say!

Sister is busy learning to shave,

Brother just loves his permanent wave,

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! Hey, hey!

Girls were girls and boys were boys when I was a tot,

Now we don't know who is who, or even what's what!

Knickers and trousers, baggy and wide,

Nobody knows who's walking inside,

Those masculine women and feminine men![102]

The relative liberalism of the decade is demonstrated by the fact that the actor William Haines, regularly named in newspapers and magazines as the No. 1 male box-office draw, openly lived in a gay relationship with his partner, Jimmie Shields. Other popular gay actors/actresses of the decade included Alla Nazimova and Ramón Novarro.[103] In 1927, Mae West wrote a play about homosexuality called The Drag,[104] and alluded to the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. It was a box-office success. West regarded talking about sex as a basic human rights issue, and was also an early advocate of gay rights.[105]

Profound hostility did not abate in more remote areas such as western Canada.[106] With the return of a conservative mood in the 1930s, the public grew intolerant of homosexuality, and gay actors were forced to choose between retiring or agreeing to hide their sexuality even in Hollywood.[107]

Psychoanalysis

Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) played a major role in psychoanalysis, which impacted avant-garde thinking, especially in the humanities and artistic fields. Historian Roy Porter wrote:

- He advanced challenging theoretical concepts such as unconscious mental states and their repression, infantile sexuality and the symbolic meaning of dreams and hysterical symptoms, and he prized the investigative techniques of free association and dream interpretation, to methods for overcoming resistance and uncovering hidden unconscious wishes.[108]

Other influential proponents of psychoanalysis included Alfred Adler (1870–1937), Karen Horney (1885–1952), Carl Jung (1875–1961), Otto Rank (1884–1939), Helene Deutsch (1884–1982), and Freud's daughter Anna (1895–1982). Adler argued that a neurotic individual would overcompensate by manifesting aggression. Porter notes that Adler's views became part of "an American commitment to social stability based on individual adjustment and adaptation to healthy, social forms".[108]

Culture

Immigration restrictions

The United States became more anti-immigration in policy. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921, intended to be a temporary measure, set numerical limitations on immigration from countries outside the Western Hemisphere, capped at approximately 357,000 total annually. The Immigration Act of 1924 made permanent a more restrictive total cap of around 150,000 per annum, based on the National Origins Formula system of quotas limiting immigration to a fraction proportionate to an ethnic group's existing share of the United States population in 1920.[109][110] The goal was to freeze the pattern of European ethnic composition, and to exclude almost all Asians. Hispanics were not restricted.[111]

Australia, New Zealand, and Canada also sharply restricted or ended Asian immigration. In Canada, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 prevented almost all immigration from Asia. Other laws curbed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.[112][113][114][115]

Prohibition

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the progressive movement gradually caused local communities in many parts of Western Europe and North America to tighten restrictions of vice activities, particularly gambling, alcohol, and narcotics (though splinters of this same movement were also involved in racial segregation in the U.S.). This movement gained its strongest traction in the U.S. leading to the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the associated Volstead Act which made illegal the manufacture, import and sale of beer, wine and hard liquor (though drinking was technically not illegal). The laws were specifically promoted by evangelical Protestant churches and the Anti-Saloon League to reduce drunkenness, petty crime, domestic abuse, corrupt saloon-politics, and (in 1918), Germanic influences. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was an active supporter in rural areas, but cities generally left enforcement to a small number of federal officials. The various restrictions on alcohol and gambling were widely unpopular leading to rampant and flagrant violations of the law, and consequently to a rapid rise of organized crime around the nation (as typified by Chicago's Al Capone).[116] In Canada, prohibition ended much earlier than in the U.S., and barely took effect at all in the province of Quebec, which led to Montreal's becoming a tourist destination for legal alcohol consumption. The continuation of legal alcohol production in Canada soon led to a new industry in smuggling liquor into the U.S.[117]

Rise of the speakeasy

Speakeasies were illegal bars selling beer and liquor after paying off local police and government officials. They became popular in major cities and helped fund large-scale gangsters operations such as those of Lucky Luciano, Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, Bugs Moran, Moe Dalitz, Joseph Ardizzone, and Sam Maceo. They operated with connections to organized crime and liquor smuggling. While the U.S. Federal Government agents raided such establishments and arrested many of the small figures and smugglers, they rarely managed to get the big bosses; the business of running speakeasies was so lucrative that such establishments continued to flourish throughout the nation. In major cities, speakeasies could often be elaborate, offering food, live bands, and floor shows. Many shows in cities such as New York, Paris, London, Berlin, and San Francisco featured female impersonators or drag performers in a wave of popularity known as the Pansy Craze.[118][119] Police were notoriously bribed by speakeasy operators to either leave them alone or at least give them advance notice of any planned raid.[120]

Literature

The Roaring Twenties was a period of literary creativity, and works of several notable authors appeared during the period. D. H. Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover was a scandal at the time because of its explicit descriptions of sex. Books that take the 1920s as their subject include:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, set in 1922 in the vicinity of New York City, is often described as the symbolic meditation on the "Jazz Age" in American literature.

- All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque recounts the horrors of World War I and also the deep detachment from German civilian life felt by many men returning from the front.

- This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald, primarily set up in post-World War I Princeton University, portrays the lives and morality of youth.

- The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway is about a group of expatriate Americans in Europe during the 1920s.

The 1920s also saw the widespread popularity of the pulp magazine. Printed on cheap pulp paper, these magazines provided affordable entertainment to the masses and quickly became one of the most popular forms of media during the decade. Many prominent writers of the 20th century would get their start writing for pulps, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dashiell Hammett, and H. P. Lovecraft. Pulp fiction magazines would last in popularity until the 1950s.[121]

Solo flight across the Atlantic

Charles Lindbergh gained sudden great international fame as the first pilot to fly solo and non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean, flying from Roosevelt Airfield (Nassau County, Long Island), New York to Paris on May 20–21, 1927. He had a single-engine airplane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", which had been designed by Donald A. Hall and custom built by Ryan Airlines of San Diego, California. His flight took 33.5 hours. The president of France bestowed on him the French Legion of Honor and, on his arrival back in the United States, a fleet of warships and aircraft escorted him to Washington, D.C., where President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Sports

The Roaring Twenties was the breakout decade for sports across the modern world. Citizens from all parts of the country flocked to see the top athletes of the day compete in arenas and stadiums. Their exploits were loudly and highly praised in the new "gee whiz" style of sports journalism that was emerging; champions of this style of writing included the legendary writers Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon in American sports literature presented a new form of heroism departing from the traditional models of masculinity.[122]

High school and junior high school students were offered to play sports that they had not been able to play in the past. Several sports, such as golf, that had previously been unavailable to the middle-class finally became available.

In 1929, driver Henry Segrave reached a record land speed of 231.44 mph in his car, the Golden Arrow.[123]

Olympics

Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, IOC officials toured the region, helping countries establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition. In some countries, such as Brazil, sporting and political rivalries hindered progress as opposing factions battled for control of the international sport. The 1924 Olympic Games in Paris and the 1928 games in Amsterdam saw greatly increased participation from Latin American athletes.[124]

Sports journalism, modernity, and nationalism excited Egypt. Egyptians of all classes were captivated by news of the Egyptian national soccer team's performance in international competitions. Success or failure in the Olympics of 1924 and 1928 was more than a betting opportunity but became an index of Egyptian independence and a desire to be seen as modern by Europe. Egyptians also saw these competitions as a way to distinguish themselves from the traditionalism of the rest of Africa.[125]

Balkans

The Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos initiated a number of programs involving physical education in the public schools and raised the profile of sports competition. Other Balkan nations also became more involved in sports and participated in several precursors of the Balkan Games, competing sometimes with Western European teams. The Balkan Games, first held in Athens in 1929 as an experiment, proved a sporting and a diplomatic success. From the beginning, the games, held in Greece through 1933, sought to improve relations among Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Albania. As a political and diplomatic event, the games worked in conjunction with an annual Balkan Conference, which resolved issues between these often-feuding nations. The results were quite successful; officials from all countries routinely praised the games' athletes and organizers. During a period of persistent and systematic efforts to create rapprochement and unity in the region, this series of athletic meetings played a key role.[126]

United States

The most popular American athlete of the 1920s was baseball player Babe Ruth. His characteristic home-run hitting heralded a new epoch in the history of the sport (the "live-ball era"), and his high style of living fascinated the nation and made him one of the highest-profile figures of the decade. Fans were enthralled in 1927 when Ruth hit 60 home runs, setting a new single-season home run record that was not broken until 1961. Together with another up-and-coming star named Lou Gehrig, Ruth laid the foundation of future New York Yankees dynasties.

A former bar room brawler named Jack Dempsey, also known as The Manassa Mauler, won the world heavyweight boxing title and became the most celebrated pugilist of his time. Enrique Chaffardet the Venezuelan Featherweight World Champion was the most sought-after boxer in 1920s Brooklyn, New York City. College football captivated fans, with notables such as Red Grange, running back of the University of Illinois, and Knute Rockne who coached Notre Dame's football program to great success on the field and nationwide notoriety. Grange also played a role in the development of professional football in the mid-1920s by signing on with the NFL's Chicago Bears. Bill Tilden thoroughly dominated his competition in tennis, cementing his reputation as one of the greatest tennis players of all time. Bobby Jones also popularized golf with his spectacular successes on the links. Ruth, Dempsey, Grange, Tilden, and Jones are collectively referred to as the "Big Five" sporting icons of the Roaring Twenties.

Organized crime

During the 19th century, vices such as gambling, alcohol, and narcotics had been popular throughout the United States in spite of not always being technically legal. Enforcement against these vices had always been spotty. Indeed, most major cities established red-light districts to regulate gambling and prostitution despite the fact that these vices were typically illegal. However, with the rise of the progressive movement in the early 20th century, laws gradually became tighter with most gambling, alcohol, and narcotics outlawed by the 1920s. Because of widespread public opposition to these prohibitions, especially alcohol, a great economic opportunity was created for criminal enterprises. Organized crime blossomed during this era, particularly the American Mafia.[127] After the 18th Amendment went into effect, bootlegging became widespread. So lucrative were these vices that some entire cities in the U.S. became illegal gaming centers with vice actually supported by the local governments. Notable examples include Miami, Florida, and Galveston, Texas. Many of these criminal enterprises would long outlast the Roaring Twenties and ultimately were instrumental in establishing Las Vegas as a gambling center.

Culture of Weimar Germany

Weimar culture was the flourishing of the arts and sciences in Germany during the Weimar Republic, from 1918 until Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933.[128] 1920s Berlin was at the hectic center of the Weimar culture. Although not part of Germany, German-speaking Austria, and particularly Vienna, is often included as part of Weimar culture.[129] Bauhaus was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts. Its goal of unifying art, craft, and technology became influential worldwide, especially in architecture.[130]

Germany, and Berlin in particular, was fertile ground for intellectuals, artists, and innovators from many fields. The social environment was chaotic, and politics were passionate. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld; political theorists Arthur Rosenberg and Gustav Meyer; and many others. Nine German citizens were awarded Nobel Prizes during the Weimar Republic, five of whom were Jewish scientists, including two in medicine.[131]

Sport took on a new importance as the human body became a focus that pointed away from the heated rhetoric of standard politics. The new emphasis reflected the search for freedom by young Germans alienated from rationalized work routines.[132]

American politics

The 1920s saw dramatic innovations in American political campaign techniques, based especially on new advertising methods that had worked so well selling war bonds during World War I. Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, the Democratic Party candidate, made a whirlwind campaign that took him to rallies, train station speeches, and formal addresses, reaching audiences totaling perhaps 2,000,000 people. It resembled the William Jennings Bryan campaign of 1896. By contrast, the Republican Party candidate Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio relied upon a "front porch campaign". It brought 600,000 voters to Marion, Ohio, where Harding spoke from his home. Republican campaign manager Will Hays spent some $8,100,000; nearly four times the money Cox's campaign spent. Hays used national advertising in a major way (with advice from adman Albert Lasker). The theme was Harding's own slogan "America First". Thus the Republican advertisement in Collier's Magazine for October 30, 1920, demanded, "Let's be done with wiggle and wobble." The image presented in the ads was nationalistic, using catchphrases like "absolute control of the United States by the United States," "Independence means independence, now as in 1776," "This country will remain American. Its next President will remain in our own country," and "We decided long ago that we objected to a foreign government of our people."[133]

1920 was the first presidential campaign to be heavily covered by the press and to receive widespread newsreel coverage, and it was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars who traveled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford, were among the celebrities to make the pilgrimage. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the Front Porch Campaign.[134] On election night, November 2, 1920, commercial radio broadcast coverage of election returns for the first time. Announcers at KDKA-AM in Pittsburgh, PA read telegraph ticker results over the air as they came in. This single station could be heard over most of the Eastern United States by the small percentage of the population that had radio receivers.

Calvin Coolidge was inaugurated as president after the sudden death of President Warren G. Harding in 1923; he was re-elected in 1924 in a landslide against a divided opposition. Coolidge made use of the new medium of radio and made radio history several times while president: his inauguration was the first presidential inauguration broadcast on radio; on February 12, 1924, he became the first American president to deliver a political speech on radio. Herbert Hoover was elected president in 1928.

Decline of labor unions

Unions grew very rapidly during the war but after a series of failed major strikes in steel, meatpacking and other industries, a long decade of decline weakened most unions and membership fell even as employment grew rapidly. Radical unionism virtually collapsed, in large part because of Federal repression during World War I by means of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

The 1920s marked a period of sharp decline for the labor movement. Union membership and activities fell sharply in the face of economic prosperity, a lack of leadership within the movement, and anti-union sentiments from both employers and the government. The unions were much less able to organize strikes. In 1919, more than 4,000,000 workers (or 21% of the labor force) participated in about 3,600 strikes. In contrast, 1929 witnessed about 289,000 workers (or 1.2% of the workforce) stage only 900 strikes. Unemployment rarely dipped below 5% in the 1920s and few workers faced real wage losses.[135]

Progressivism in 1920s

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. The politics of the 1920s was unfriendly toward the labor unions and liberal crusaders against business and so many, if not all, historians who emphasize those themes write off the decade. Urban cosmopolitan scholars recoiled at the moralism of prohibition and the intolerance of the nativists of the KKK and denounced the era. Historian Richard Hofstadter, for example, wrote in 1955 that prohibition "was a pseudo-reform, a pinched, parochial substitute for reform" that "was carried about America by the rural-evangelical virus."[136] However, as Arthur S. Link emphasized, the progressives did not simply roll over and play dead.[137] Link's argument for continuity through the 1920s stimulated a historiography that found Progressivism to be a potent force. Palmer, pointing to people like George Norris, wrote, "It is worth noting that progressivism, whilst temporarily losing the political initiative, remained popular in many western states and made its presence felt in Washington during both the Harding and Coolidge presidencies."[138] Gerster and Cords argued, "Since progressivism was a 'spirit' or an 'enthusiasm' rather than an easily definable force with common goals, it seems more accurate to argue that it produced a climate for reform which lasted well into the 1920s, if not beyond."[139]

Even the Klan has been seen in a new light as numerous social historians reported that Klansmen were "ordinary white Protestants" primarily interested in purification of the system, which had long been a core progressive goal.[140] In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan experienced a resurgence, spread all over the country, and found a significant popularity that has lingered to this day in the Midwest. It was claimed at the height of the second incarnation of the KKK, its membership exceeded 4 million people nationwide. The Klan did not shy away from using burning crosses and other intimidation tools to strike fear into their opponents, who included not just blacks but also Catholics, Jews, and anyone else who was not a white Protestant.[141] Massacres of black people were common in the 1920s. Tulsa, 1921: On May 31, 1921, a White mob descended on "Black Wall Street", a prosperous Black neighborhood in Tulsa. Over the next two days, they murdered more than 300 people, burned down 40 city blocks and left 10,000 Black residents homeless.[142]

Business progressivism

What historians have identified as "business progressivism," with its emphasis on efficiency and typified by Henry Ford and Herbert Hoover[143] reached an apogee in the 1920s. Reynold M. Wik, for example, argues that Ford's "views on technology and the mechanization of rural America were generally enlightened, progressive, and often far ahead of his times."[144]

Tindall stresses the continuing importance of the progressive movement in the South in the 1920s involving increased democracy, efficient government, corporate regulation, social justice, and governmental public service.[145][146] William Link finds political progressivism dominant in most of the South in the 1920s.[147] Likewise, it was influential in Midwest.[148] In Birmingham, Alabama, the Klan violently repressed mixed-race unions but joined with white Protestant workers in a political movement that enacted reforms beneficial to the white working class. But Klan attention to working-class interests was circumstantial and rigidly restricted by race, religion, and ethnicity.[149]

Historians of women and of youth emphasize the strength of the progressive impulse in the 1920s.[150] Women consolidated their gains after the success of the suffrage movement, and moved into causes such as world peace,[151] good government, maternal care (the Sheppard–Towner Act of 1921),[152] and local support for education and public health.[153] The work was not nearly as dramatic as the suffrage crusade, but women voted[154] and operated quietly and effectively. Paul Fass, speaking of youth, wrote "Progressivism as an angle of vision, as an optimistic approach to social problems, was very much alive."[155] The international influences which had sparked a great many reform ideas likewise continued into the 1920s, as American ideas of modernity began to influence Europe.[156]

There is general agreement that the Progressive Era was over by 1932, especially since a majority of the remaining progressives opposed the New Deal.[157]

Canadian politics

Canadian politics were dominated federally by the Liberal Party of Canada under William Lyon Mackenzie King. The federal government spent most of the decade disengaged from the economy and focused on paying off the large debts amassed during the war and during the era of railway over expansion. After the booming wheat economy of the early part of the century, the prairie provinces were troubled by low wheat prices. This played an important role in the development of Canada's first highly successful third political party, the Progressive Party of Canada that won the second most seats in the 1921 national election. As well with the creation of the Balfour Declaration of 1926, Canada achieved with other British former colonies autonomy, forming the British Commonwealth.

End of an era

Black Tuesday

The Dow Jones Industrial Stock Index had continued its upward move for weeks, and coupled with heightened speculative activities, it gave an illusion that the bull market of 1928 to 1929 would last forever. On October 29, 1929, also known as Black Tuesday, stock prices on Wall Street collapsed. The events in the United States added to a worldwide depression, later called the Great Depression, that put millions of people out of work around the world throughout the 1930s.

Repeal of Prohibition

The 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, was proposed on February 20, 1933. The choice to legalize alcohol was left up to the states, and many states quickly took this opportunity to allow alcohol. Prohibition was officially ended with the ratification of the amendment on December 5, 1933.

In popular culture

Television and film

The television show Boardwalk Empire is set chiefly in Atlantic City, New Jersey, during the Prohibition era of the 1920s.

The film The Great Gatsby is a 2013 historical romantic drama film based on the 1925 novel of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Music

For the 1987 album Bad, singer Michael Jackson's single "Smooth Criminal" featured an iconic video that took place during Prohibition in a speak-easy setting. This is also where his iconic anti-gravity lean was debuted.

For the classic album Rebel of the Underground released June 21, 2013, by recording artist Marcus Orelias, the album featured the song titled "Roaring 20s".

On September 2, 2013, musical duo Rizzle Kicks released their second album titled Roaring 20s under Universal Island.

On July 20, 2022, rap artist Flo Milli released her commercial debut album, You Still Here, Ho? which featured a bonus track called "Roaring 20s". The song was accompanied with a 1920s themed video.

Pray for the Wicked, the sixth studio album by American pop rock solo project Panic! at the Disco, released on June 22, 2018, features a song titled "Roaring 20s".

My Roaring 20s is the second studio album by American rock group Cheap Girls; it was released on October 9, 2009, and the title is a reference to the era.

See also

References

- ^ Anton Gill, A Dance Between Flames: Berlin Between the Wars (1994).

- ^ Fraga, Enrique Alberto (February 16, 2020). "El rugido centenario de los años locos". La Nación (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Elsey, Brenda (2011). Citizens and Sportsmen: Fútbol and Politics in Twentieth-Century Chile. University of Texas Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780292726307. Retrieved May 25, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marc Moscato, Brains, Brilliancy, Bohemia: Art & Politics in Jazz-Age Chicago (2009)

- ^ Hall, Lesley A. (1996). "Impotent ghosts from no man's land, flappers' boyfriends, or crypto-patriarchs? Men, sex and social change in 1920s Britain". Social History. 21 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1080/03071029608567956.

- ^ David Robinson, Hollywood in the Twenties (1968)

- ^ David Wallace, Capital of the World: A Portrait of New York City in the Roaring Twenties (2011)

- ^ Jody Blake, Le Tumulte Noir: modernist art and popular entertainment in jazz-age Paris, 1900–1930 (1999)

- ^ Jack Lindsay, The roaring twenties: literary life in Sydney, New South Wales in the years 1921-6 (1960)

- ^ Andrew Lamb (2000). 150 Years of Popular Musical Theatre. Yale University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-300-07538-0.

- ^ Pamela Horn, Flappers: The Real Lives of British Women in the Era of the Great Gatsby (2013)

- ^ Angela J. Latham, Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the American 1920s (2000)

- ^ Madeleine Ginsburg, Paris fashions: the art deco style of the 1920s (1989)

- ^ "Dawes Plan". encyclopedia.com. August 13, 2018. Retrieved October 21, 2023.

- ^ Bärbel Schrader, and Jürgen Schebera. The" golden" twenties: art and literature in the Weimar Republic (1988)

- ^ Paul N. Hehn (2005). A Low Dishonest Decade: The Great Powers, Eastern Europe, and the Economic Origins of World War II, 1930–1941. Continuum. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8264-1761-9.

- ^ Based on data in Susan Carter, ed. Historical Statistics of the US: Millennial Edition (2006) series Ca9

- ^ "Roaring Twenties". U-S-History.com. Online Highways. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ a b George H. Soule, Prosperity Decade: From War to Depression: 1917–1929 (1947)

- ^ "Model T Facts" (Press release). US: Ford. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ John Steele Gordon (March 1, 2007). "10 Moments That Made American Business". American Heritage. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Michigan History". Detroit News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ Sorensen 1956, pp. 217–219.

- ^ Hounshell 1984, pp. 263–264

- ^ Sloan 1964, pp. 162–163

- ^ "STATE MOTOR VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS, BY YEARS, 1900 – 1995 1/" (PDF). Fhwa.dot.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Foreman-Peck, James (1982). "The American Challenge of the Twenties: Multinationals and the European Motor Industry". The Journal of Economic History. 42 (4): 865–881. doi:10.1017/S0022050700028370. S2CID 154328982.

- ^ Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1927–30: Part II" Archived May 26, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ Stephens, E. J.; Wanamaker, Marc (2010). Early Warner Bros. Studios. Arcadia Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-738-58091-3.

- ^ Allen, Bob (Autumn 1997). "Why The Jazz Singer?". AMPS Newsletter. Association of Motion Picture Sound. Archived from the original on October 22, 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Geduld (1975), p. 166.

- ^ Crafton (1997), p. 148.

- ^ Crafton (1997), p. 390.

- ^ Steamboat Willie (1929) Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine at Screen Savour

- ^ Robertson (2001), p. 63.

- ^ Robertson (2001), p. 173.

- ^ Jackson 2012, pp. 512–516.

- ^ Spencer Dunmore, Undaunted: Long-Distance Flyers in the Golden Age of Aviation (2004)

- ^ "Patent US1925554 – Television apparatus and the like". Google.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ R. F. Tiltman, How "Stereoscopic" Television is Shown Archived October 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Radio News, November 1928

- ^ Interview with Paul Lyons Archived February 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Historian and Control and Information Officer at Glasgow Central Station

- ^ "Historic Figures: John Logie Baird (1888–1946)". BBC. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ^ Wainwright M, Swan HT; Swan (January 1986). "C.G. Paine and the earliest surviving clinical records of penicillin therapy". Medical History. 30 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1017/S0025727300045026. PMC 1139580. PMID 3511336.

- ^ Howie, J (1986). "Penicillin: 1929–40". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 293 (6540): 158–159. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6540.158. PMC 1340901. PMID 3089435.

- ^ Wainwright, M (1987). "The history of the therapeutic use of crude penicillin". Medical History. 31 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1017/s0025727300046305. PMC 1139683. PMID 3543562.

- ^ Flink, James J. (1972). "Three Stages of American Automobile Consciousness". American Quarterly. 24 (4): 451–473. doi:10.2307/2711684. JSTOR 2711684.

- ^ John A. Jakle, and Keith A. Sculle, Fast food: Roadside restaurants in the automobile age (2002).

- ^ Christopher W. Wells, Car Country: Automobiles, Roads and the Shaping of the Modern American Landscape, 1890–1929 (2004).

- ^ David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social meanings of a new technology, 1880–1940 (1992)

- ^ Dan Bryan. "The Great (Farm) Depression of the 1920s". American History USA. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, and Katherine Holden, eds. International encyclopedia of women's suffrage (Abc-Clio Inc, 2000).

- ^ Rosemary Skinner Keller; Rosemary Radford Ruether; Marie Cantlon (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana UP. p. 1033. ISBN 0-253-34688-6.

- ^ Josephine Donovan (2012). Feminist Theory, Fourth Edition: The Intellectual Traditions. A&C Black. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4411-6830-6.

- ^ Julie V. Gottlieb (2016). 'Guilty Women', Foreign Policy, and Appeasement in Inter-War Britain. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-137-31660-8.

- ^ D. J. Taylor (2010). Bright Young People: The Lost Generation of London's Jazz Age. Macmillan. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4299-5895-0.

- ^ Geduld, Harry M. (1975). The Birth of the Talkies: From Edison to Jolson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10743-1

- ^ "Mickey Mouse Character History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ "Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Character History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on March 7, 2011. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ J. G. Ellrod, The Stars of Hollywood Remembered: Career Biographies of 81 Actors and Actesses of the Golden Era, 1920s–1950s (1997).

- ^ Arnold Shaw, The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920s (Oxford UP, 1989).

- ^ Kathy J. Ogren, The Jazz Revolution: Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz (1989) p. 11.

- ^ DeVeaux, Scott (1991). "Constructing the Jazz Tradition: Jazz Historiography" (PDF). Black American Literature Forum. 25 (3): 525–60. doi:10.2307/3041812. JSTOR 3041812. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz (Oxford UP, 2011).

- ^ Ralph G. Giordano, Satan in the dance hall: Rev. John Roach Straton, social dancing, and morality in 1920s New York City (2008).

- ^ Robinson, Danielle (2006). "'Oh, You Black Bottom!' Appropriation, Authenticity, and Opportunity in the Jazz Dance Teaching of 1920s New York". Dance Research Journal. 38 (1–2): 19–42. doi:10.1017/S0149767700007312.

- ^ Spring, Howard (1997). "Swing and the Lindy Hop: Dance, Venue, Media, and Tradition". American Music. 15 (2): 183–207. doi:10.2307/3052731. JSTOR 3052731.

- ^ Frances Rust (1969). Dance in Society: An Analysis of the Relationship Between the Social Dance and Society in England from the Middle Ages to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-134-55407-2.

- ^ Jim Cox, Music radio: the great performers and programs of the 1920s through early 1960s (McFarland, 2005).

- ^ Roberts, Mary Louise (1993). "Samson and Delilah Revisited: The Politics of Women's Fashion in 1920s France". The American Historical Review. 98 (3): 657–684. doi:10.1086/ahr/98.3.657.

- ^ Bliss, Simon (2016). "'L'intelligence de la parure': Notes on Jewelry Wearing in the 1920s". Fashion Theory. 20 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2015.1077652. S2CID 191700478.

- ^ Zdatny, Steven (1997). "The Boyish Look and the Liberated Woman: The Politics and Aesthetics of Women's Hairstyles". Fashion Theory. 1 (4): 367–397. doi:10.2752/136270497779613639.

- ^ Angel Kwolek-Folland, Engendering Business: Men and Women in the Corporate Office, 1870–1930 (Johns Hopkins UP, 1994).

- ^ Carolyn Kitch, The Girl on the Magazine Cover (University of North Carolina Press, 2001). pp. 122–23.

- ^ Sylvester, Nina (2007). "Before Cosmopolitan: The Girl in German women's magazines in the 1920s". Journalism Studies. 8 (4): 550–554. doi:10.1080/14616700701411953. S2CID 220410086.

- ^ Lucy Moore, Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties (Atlantic Books, 2015).

- ^ Bingham, Jane (2012). Popular Culture: 1920–1938. Chicago Illinois: Heinemann Library.

- ^ Paula S. Fass, The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920s (Oxford UP, 1977)

- ^ Litchfield Historical Society (2015). The House of Worth: Fashion Sketches, 1916–1918. Courier Dover. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-486-79924-7.

- ^ Lurie, Alison (1981). The Language of Clothes. New York: New York: Random House. ISBN 9780394513027.

- ^ Brand, Jan (2007). Fashion & Accessories. Arnhem :Terra.

- ^ Bingham, Adrian (2004). "'An Era of Domesticity'? Histories of Women and Gender in Interwar Britain". Cultural and Social History. 1 (2): 225–233. doi:10.1191/1478003804cs0014ra. S2CID 145681847.

- ^ Alison Light, Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars (1991) p. 9.

- ^ Brown, Dorothy M. Setting a Course: American Women in the 1920s (Twayne Publishers, 1987) p. 33.

- ^ Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History (2002). p. 256.

- ^ Linda Eisenmann, Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United States (1998) p. 440.

- ^ Rabinovitch-Fox, Einav (2016). "Baby, You Can Drive My Car: Advertising Women's Freedom in 1920s America". American Journalism. 33 (4): 372–400. doi:10.1080/08821127.2016.1241641. S2CID 157498769.

- ^ Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 219.

- ^ Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States p. 237.

- ^ Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States pp 237, 288.

- ^ Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History (McGraw–Hill, 2002) p. 246.

- ^ Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History p. 274.

- ^ Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History, pp. 28–3.

- ^ Ruth Schwartz Cowan, Two Washes in the Morning and a Bridge Party at Night: The American Housewife between the Wars (1976) p. 184.

- ^ Nicholas Atkin; Michael Biddiss (2008). Themes in Modern European History, 1890–1945. Routledge. pp. 243–44. ISBN 978-1-134-22257-5.

- ^ Gregory M. Luebbert, Liberalism, fascism, or social democracy: Social classes and the political origins of regimes in interwar Europe (Oxford UP, 1991).

- ^ Julian Jackson (2009). Living in Arcadia: Homosexuality, Politics, and Morality in France from the Liberation to AIDS. University of Chicago Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-226-38928-8.

- ^ Florence Tamagne (2006). A History of Homosexuality in Europe: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919–1939. Algora Publishing. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- ^ Crouthamel, Jason (2011). "'Comradeship' and 'Friendship': Masculinity and Militarisation in Germany's Homosexual Emancipation Movement after the First World War: Masculinity and Militarisation in Germany's Homosexual Emancipation Movement". Gender & History. 23 (1): 111–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2010.01626.x. S2CID 143240617.

- ^ Ramsey, Glenn (2007). "The Rites of Artgenossen: Contesting Homosexual Political Culture in Weimar Germany". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 17 (1): 85–109. doi:10.1353/sex.2008.0009. PMID 19260158. S2CID 22292105.

- ^ The song was written by Edgar Leslie (words) and James V. Monaco (music) and featured in Hugh J. Ward's Musical Comedy "Lady Be Good."

- ^ Artists who recorded this song include: 1. Frank Harris (Irving Kaufman), (Columbia 569D,1/29/26) 2. Bill Meyerl & Gwen Farrar (the UK, 1926) 3. Joy Boys (the UK, 1926) 4. Harry Reser's Six Jumping Jacks (the UK, 2/13/26) 5. Hotel Savoy Opheans (HMV 5027, UK, 1927, aka Savoy Havana Band) 6. Merrit Brunies & His Friar's Inn Orchestra on Okeh 40593, 3/2/26

- ^ A full reproduction of the original sheet music with the complete lyrics can be found at: http://nla.gov.au/nla.mus-an6301650 Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mann, William J., Wisecracker: the life and times of William Haines, Hollywood's first openly gay star (Viking, 1998) pp 2–6, 12–13, 80–83.

- ^ See Three Plays by Mae West: Sex, The Drag and Pleasure Man Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine