South Carolina (/ˌkærəˈlaɪnə/ ⓘ KARR-ə-LIE-nə) is a state in the coastal Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia to the southwest across the Savannah River. Along with North Carolina, it makes up the Carolinas region of the East Coast. South Carolina is the 40th-largest and 23rd-most populous U.S. state with a recorded population of 5,118,425 according to the 2020 census.[2] In 2019, its GDP was $213.45 billion. South Carolina is composed of 46 counties. The capital is Columbia with a population of 136,632 in 2020;[4] while its most populous city is Charleston with a 2020 population of 150,227.[5] The Greenville-Spartanburg-Anderson, SC Combined Statistical Area is the most populous combined metropolitan area in the state, with an estimated 2023 population of 1,590,636.[6]

South Carolina was named in honor of King Charles I of England, who first formed the English colony, with Carolus being Latin for "Charles".[7] In 1712 the Province of South Carolina was formed. One of the original Thirteen Colonies, South Carolina became a royal colony in 1719. During the American Revolutionary War, South Carolina was the site of major activity among the American colonies, with more than 200 battles and skirmishes fought within the state.[8] South Carolina became the eighth state to ratify the U.S. Constitution on May 23, 1788. A slave state, it was the first state to vote in favor of secession from the Union on December 20, 1860. After the American Civil War, it was readmitted to the Union on July 9, 1868.

During the early-to-mid 20th century, the state started to see economic progress as many textile mills and factories were built across the state. The civil rights movement of the mid-20th century helped end segregation and legal discrimination policies within the state. Economic diversification in South Carolina continued to pick up speed during and in the ensuing decades after World War II. In the early 21st century, South Carolina's economy is based on industries such as aerospace, agribusiness, automotive manufacturing, and tourism.[9]

Within South Carolina from east to west are three main geographic regions, the Atlantic coastal plain, the Piedmont, and the Blue Ridge Mountains in the northwestern corner of Upstate South Carolina. South Carolina has primarily a humid subtropical climate, with hot, humid summers and mild winters. Areas in the Upstate have a subtropical highland climate. Along South Carolina's eastern coastal plain are many salt marshes and estuaries. South Carolina's southeastern Lowcountry contains portions of the Sea Islands, a chain of barrier islands along the Atlantic Ocean.

History

Precolonial period

There is evidence of human activities in the area dating to about 50,000 years ago.[10] At the time Europeans arrived, marking the end of the Pre-Columbian era around 1600, there were many separate Native American tribes, the largest being the Cherokee and the Catawba, with the total population being up to 20,000.[11]

Up the rivers of the eastern coastal plain lived about a dozen tribes of Siouan background. Along the Savannah River were the Apalachee, Yuchi, and the Yamasee. Further west were the Cherokee, and along the Catawba River, the Catawba. These tribes were village-dwellers, relying on agriculture as their primary food source.[11] The Cherokee lived in wattle and daub houses made with wood and clay, roofed with wood or thatched grass.[12]

About a dozen or more separate small tribes summered on the coast harvesting oysters and fish, and cultivating corn, peas and beans. Travelling inland as much as 50 miles (80 km) mostly by canoe, they wintered on the coastal plain, hunting deer and gathering nuts and fruit. The names of these tribes survive in place names like Edisto Island, Kiawah Island, and the Ashepoo River.[11]

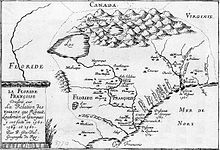

Exploration

The Spanish were the first Europeans in the area. From June 24 to July 14, 1521, they explored the land around Winyah Bay. On October 8, 1526, they founded San Miguel de Gualdape, near present-day Georgetown, South Carolina. It was the first European settlement in what is now the contiguous United States. Established with five hundred settlers, it was abandoned eight months later by one hundred and fifty survivors. In 1540, Hernando de Soto explored the region and the main town of Cofitachequi, where he captured the queen of the Maskoki (Muscogee) and the Chelaque (Cherokee) who had welcomed him.

In 1562 French Huguenots established a settlement at what is now the Charlesfort-Santa Elena archaeological site on Parris Island. Many of these settlers preferred a natural life far from civilization and the atrocities of the Wars of Religion. The garrison lacked supplies, however, and the soldiers (as in the France Antarctique) soon ran away. The French returned two years later but settled in present-day Florida rather than South Carolina.[11]

Colonization

Sixty years later, in 1629, the King of England Charles I established the Province of Carolina, an area covering what is now South and North Carolina, Georgia and Tennessee. In 1663, Charles II granted the land to eight Lords Proprietors in return for their financial and political assistance in restoring him to the throne in 1660.[13] Anthony Ashley Cooper, one of the Lord Proprietors, planned the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina and wrote the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which laid the basis for the future colony.[14] His utopia was inspired by John Locke, an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "Father of Liberalism".

The Carolina slave trade, which included both trading and direct raids by colonists,[15]: 109 was the largest among the British colonies in North America.[15]: 65 Between 1670 and 1715, between 24,000 and 51,000 captive Native Americans were exported from South Carolina – more than the number of Africans imported to the colonies of the future United States during the same period.[16][15]: 237 Additional enslaved Native Americans were exported from South Carolina to other U.S. colonies.[16] The historian Alan Gallay says, "the trade in Indian slaves was at the center of the English empire's development in the American South. The trade in Indian slaves was the most important factor affecting the South in the period 1670 to 1715".[16]

In the 1670s, English planters from Barbados established themselves near what is now Charleston. Settlers from all over Europe built rice plantations in the South Carolina Lowcountry, east of the Atlantic Seaboard fall line. Plantation labor was done by African slaves who formed the majority of the population by 1720.[17] Another cash crop was the indigo plant, a plant source of blue dye, developed by Eliza Lucas.

Meanwhile, Upstate South Carolina, west of the Fall Line, was settled by small farmers and traders, who displaced Native American tribes westward. Colonists overthrew the proprietors' rule, seeking more direct representation. In 1712, the former Province of Carolina split into North and South Carolina. In 1719, South Carolina was officially made a royal colony.

South Carolina prospered from the fertility of the lowcountry and the harbors, such as at Charleston. It allowed religious toleration, encouraging settlement, and trade in deerskin, lumber, and beef thrived. Rice cultivation was developed on a large scale on the back of slave labor.

By the second half of the 1700s, South Carolina was one of the richest of the Thirteen Colonies.[17]

The American Revolution

On March 26, 1776, the colony adopted the Constitution of South Carolina,[18] electing John Rutledge as the state's first president. In February 1778, South Carolina became the first state to ratify the Articles of Confederation,[19] the initial governing document of the United States, and in May 1788, South Carolina ratified the United States Constitution, becoming the eighth state to enter the union.

During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), about a third of combat action took place in South Carolina,[20] more than any other state.[17] Inhabitants of the state endured being invaded by British forces and an ongoing civil war between loyalists and partisans that devastated the backcountry.[20] It is estimated 25,000 slaves (30% of those in South Carolina) fled, migrated or died during the war.[21]

Antebellum

America's first census in 1790 put the state's population at nearly 250,000. By the 1800 census, the population had increased 38 per cent to nearly 340,000 of which 146,000 were slaves. At that time South Carolina had the largest population of Jews in the sixteen states of the United States, mostly based in Savannah and Charleston,[22] the latter being the country's fifth largest city.[23]

In the Antebellum period (before the Civil War) the state's economy and population grew. Cotton became an important crop after the invention of the cotton gin. While nominally democratic, from 1790 until 1865, wealthy male landowners were in control of South Carolina. For example, a man was not eligible to sit in the State House of Representatives unless he possessed an estate of 500 acres of land and 10 Negroes, or at least 150 pounds sterling.[24]

Columbia, the new state capital was founded in the center of the state, and the State Legislature first met there in 1790. The town grew after it was connected to Charleston by the Santee Canal in 1800, one of the first canals in the United States.

As dissatisfaction of the planters ruling class with the federal government grew, in the 1820s John C. Calhoun became a leading proponent of states' rights, limited government, nullification of the U.S. Constitution, and free trade. In 1832, the Ordinance of Nullification declared federal tariff laws unconstitutional and not to be enforced in the state, leading to the Nullification Crisis. The federal Force Bill was enacted to use whatever military force necessary to enforce federal law in the state, bringing South Carolina back into line.

An 1831 House Report from the Committee on Military Affairs noted that

Before the commencement of the war with Great Britain, and for a long time afterwards, the State of South Carolina was almost destitute of any of the means of military protection, excepting as such could be furnished by her own resources. In the harbor of Charleston alone were there any forts, and these were in so feeble a condition, that at a period, when a British squadron was engaged in sounding the depth of water off the bar, and its commander apparently meditating an attack upon the forts, the quantity of gunpowder in the harbor, belonging to the United States, was not more than sufficient to have enabled the garrison to fire a single round.[25]

In the United States presidential election of 1860, voting was sharply divided, with the South voting for the Southern Democrats and the North for Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party. Lincoln was anti-slavery, did not acknowledge the right to secession, and would not yield federal property in Southern states. Southern secessionists believed Lincoln's election meant long-term doom for their slavery-based agrarian economy and social system.[26]

Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860. The state House of Representatives three days later passed the "Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act",[27] and within weeks South Carolina became the first state to secede.[17]

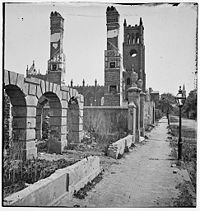

Civil War 1861–1865

On April 12, 1861, Confederate batteries began shelling the Union Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, and the American Civil War began. In November of that year, the Union attacked Port Royal Sound and soon occupied Beaufort County and the neighboring Sea Islands. For the rest of the war, this area served as a Union base and staging point for other operations. Whites abandoned their plantations,[28] leaving behind about ten thousand enslaved people. Several Northern charities partnered with the federal government to help these people run the cotton farms themselves under the Port Royal Experiment. Workers were paid by the pound harvested and thus became the first enslaved people freed by the Union forces to earn wages.[29]

Although the state was not a major battleground, the war ruined the state's economy. More than 60,000 soldiers from South Carolina served in the war,[28] with the state losing an estimated 18,000 troops.[30] Though no regiments of Southern Unionists were formed in South Carolina due to a smaller unionist presence, the Upstate region of the state would be a haven for Confederate Army deserters and resisters, as they used the Upstate topography and traditional community relations to resist service in the Confederate ranks.[31] At the end of the war in early 1865, the troops of General William Tecumseh Sherman marched across the state devastating plantations and most of Columbia. South Carolina would be readmitted to the Union on July 9, 1868.

Reconstruction 1865–1877

In Texas vs. White (1869), the Supreme Court ruled the ordinances of secession (including that of South Carolina) were invalid, and thus those states had never left the Union. However, South Carolina did not regain representation in Congress until that date.

Until the 1868 presidential election, South Carolina's legislature, not the voters, chose the state's electors for the presidential election. South Carolina was the last state to choose its electors in this manner. During Reconstruction, South Carolina maintained a majority-black government, which lasted until approximately 1876 when Democrats and former Confederates committed voter fraud to regain power.[32][33][34] On October 19, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant suspended habeas corpus in nine South Carolina counties under the authority of the Ku Klux Klan Act.[35] Led by Grant's Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, hundreds of Klansmen were arrested while 2,000 Klansmen fled the state.[35] This was done to suppress Klan violence against African-American and white voters in the South.[35] In the mid-to-late 1870s, white Democrats used paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts to intimidate and terrorize black voters. They regained political control of the state under conservative white "Redeemers" and pro-business Bourbon Democrats. In 1877, the federal government withdrew its troops as part of the Compromise of 1877 that ended Reconstruction.

Populist and agrarian movements

The state became a hotbed of racial and economic tensions during the Populist and Agrarian movements of the 1890s. A Republican-Populist biracial coalition took power away from White Democrats temporarily. To prevent that from happening again, Democrats gained passage of a new constitution in 1895 which effectively disenfranchised almost all blacks and many poor whites by new requirements for poll taxes, residency, and literacy tests that dramatically reduced the voter rolls. By 1896, only 5,500 black voters remained on the voter registration rolls, although they constituted a majority of the state's population.[36] The 1900 census demonstrated the extent of disenfranchisement: the 782,509 African American citizens comprised more than 58% of the state's population, but they were essentially without any political representation in the Jim Crow society.[37]

The 1895 constitution overturned local representative government, reducing the role of the counties to agents of state government, effectively ruled by the General Assembly, through the legislative delegations for each county. As each county had one state senator, that person had considerable power. The counties lacked representative government until home rule was passed in 1975.[38]

Governor "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman, a Populist, led the effort to disenfranchise the blacks and poor whites, although he controlled Democratic state politics from the 1890s to 1910 with a base among poor white farmers. During the constitutional convention in 1895, he supported another man's proposal that the state adopt a one-drop rule, as well as prohibit marriage between whites and anyone with any known African ancestry.

Some members of the convention realized prominent white families with some African ancestry could be affected by such legislation. In terms similar to a debate in Virginia in 1853 on a similar proposal (which was dropped), George Dionysius Tillman said in opposition:

If the law is made as it now stands respectable families in Aiken, Barnwell, Colleton, and Orangeburg will be denied the right to intermarry among people with whom they are now associated and identified. At least one hundred families would be affected to my knowledge. They have sent good soldiers to the Confederate Army, and are now landowners and taxpayers. Those men served creditably, and it would be unjust and disgraceful to embarrass them in this way. It is a scientific fact that there is not one full-blooded Caucasian on the floor of this convention. Every member has in him a certain mixture of ... colored blood. The pure-blooded white has needed and received a certain infusion of darker blood to give him readiness and purpose. It would be a cruel injustice and the source of endless litigation, of scandal, horror, feud, and bloodshed to undertake to annul or forbid marriage for a remote, perhaps obsolete trace of Negro blood. The doors would be open to scandal, malice and greed; to statements on the witness stand that the father or grandfather or grandmother had said that A or B had Negro blood in their veins. Any man who is half a man would be ready to blow up half the world with dynamite to prevent or avenge attacks upon the honor of his mother in the legitimacy or purity of the blood of his father.[39][40][41][42]

The state postponed such a one-drop law for years. Virginian legislators adopted a one-drop law in 1924, forgetting that their state had many people of mixed ancestry among those who identified as white.

20th century

Early in the 20th century, South Carolina developed a thriving textile industry. The state also converted its main agricultural base from cotton, to more profitable crops. It would attract large military bases during World War I, through its majority Democratic congressional delegation, part of the one-party Solid South following disfranchisement of blacks.

In the late 19th century, South Carolina would implement Jim Crow laws which enforced racial segregation policies until the 1960s. During the early-to-mid part of the 20th century, millions of African Americans left South Carolina and other southern states for jobs, opportunities, and relative freedom in U.S. cities outside the former Confederate states. In total from 1910 to 1970, 6.5 million blacks left the South in the Great Migration. By 1930, South Carolina had a white majority population for the first time since 1708.[43] South Carolina was one of several states that initially rejected the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) giving women the right to vote. The South Carolina legislature later ratified the amendment on July 1, 1969.

The struggle of the civil rights movement took place in South Carolina, as they did in other Southern states and elsewhere within the country. South Carolina would experience a much less violent movement than other Deep South states.[44] This tranquil transition from a Jim Crow society occurred because the state's white and black leaders were willing to accept slow change, rather than being utterly unwilling to accept change at all.[45] Other South Carolina political figures, like Sen. Strom Thurmond, on the other hand, were among the nation's most radical and effective opponents of social equality and integration.

During the mid-to-late 20th century, South Carolina started to see economic progress first in the textile industry and then in manufacturing. Tourism also started to form into a major industry within the state during the 20th century, especially in areas such as Myrtle Beach and Charleston.[46]

21st century

As the 21st century progresses, South Carolina has attracted new business by having a 5% corporate income tax rate, no state property tax, no local income tax, no inventory tax, no sales tax on manufacturing equipment, industrial power or materials for finished products; no wholesale tax, and no unitary tax on worldwide profits.[47]

South Carolina was one of the first states to stop paying for "early elective" deliveries of babies, under either Medicaid and private insurance.[48][49] The term early elective is defined as a labor induction or Cesarean section between 37 and 39 weeks. The change was intended to result in healthier babies and fewer costs for the state of South Carolina.[50]

On November 20, 2014, South Carolina became the 35th state to legalize same-sex marriages, when a federal court ordered the change.[51]

As of 2022, South Carolina had one of the lowest percentages among all states of women in state legislature, at 17.6% (only five states had a lower percentage; the national average is 30.7%; with the highest percentage being in Nevada at 61.9%).[52]

Geography

Regions

The state can be divided into three natural geographic areas which then can be subdivided into five distinct cultural regions. The natural environment is divided from east to west by the Atlantic coastal plain, the Piedmont, and the Blue Ridge Mountains. Culturally, the coastal plain is split into the Lowcountry and the Pee Dee region. While, the upper Piedmont region is referred to as the Piedmont and the lower Piedmont region is referred to as the Midlands. The area surrounding the Blue Ridge Mountains is known as the Upstate.[53] The Atlantic Coastal Plain makes up two-thirds of the state. Its eastern border is the Sea Islands, a chain of tidal and barrier islands. The border between the lowcountry and the upcountry is defined by the Atlantic Seaboard fall line, which marks the limit of navigable rivers.

Altogether, the state has a total area of 32,020.49 square miles (82,932.7 km2), of which 30,060.70 square miles (77,856.9 km2) is land and 1,959.79 square miles (5,075.8 km2) (6.12%) is water.[54]

Atlantic Coastal Plain

The Atlantic Coastal plain consists of sediments and sedimentary rocks that range in age from Cretaceous to Present. The terrain is relatively flat and the soil is composed predominantly of sand, silt, and clay. Areas with better drainage make excellent farmland, though some land is swampy. An unusual feature of the coastal plain is a large number of low-relief topographic depressions named Carolina bays. The bays tend to be oval, lining up in a northwest to southeast orientation. The eastern portion of the coastal plain contains many salt marshes and estuaries, as well as natural ports such as Georgetown and Charleston. The natural areas of the coastal plain are part of the Middle Atlantic coastal forests ecoregion.[55]

The Sandhills or Carolina Sandhills is a 10–35 mi (16–56 km) wide region within the Atlantic Coastal Plain province, along the inland margin of this province. The Carolina Sandhills are interpreted as eolian (wind-blown) sand sheets and dunes that were mobilized episodically from approximately 75,000 to 6,000 years ago. Most of the published luminescence ages from the sand are coincident with the last glaciation, a time when the southeastern United States was characterized by colder air temperatures and stronger winds.[56]

Piedmont

Much of Piedmont consists of Paleozoic metamorphic and igneous rocks, and the landscape has relatively low relief. Due to the changing economics of farming, much of the land is now reforested in loblolly pine for the lumber industry. These forests are part of the Southeastern mixed forests ecoregion.[55] At the southeastern edge of Piedmont is the fall line, where rivers drop to the coastal plain. The fall line was an important early source of water power. Mills built to this resource encouraged the growth of several cities, including the capital, Columbia. The larger rivers are navigable up to the fall line, providing a trade route for mill towns.

The northwestern part of Piedmont is also known as the Foothills. The Cherokee Parkway is a scenic driving route through this area. This is where Table Rock State Park is located.

Blue Ridge

The Blue Ridge consists primarily of Precambrian metamorphic rocks, and the landscape has relatively high relief. The Blue Ridge Region contains an escarpment of the Blue Ridge Mountains that continues into North Carolina and Georgia as part of the southern Appalachian Mountains. Sassafras Mountain, South Carolina's highest point at 3,560 feet (1,090 m), is in this area.[57] Also in this area is Caesars Head State Park. The environment here is that of the Appalachian-Blue Ridge forests ecoregion.[55] The Chattooga River, on the border between South Carolina and Georgia, is a favorite whitewater rafting destination.

Lakes

South Carolina has several major lakes covering over 683 square miles (1,770 km2). All major lakes in South Carolina are human-made. The following are the lakes listed by size.[58][59]

- Lake Marion 110,000 acres (450 km2)

- Lake Strom Thurmond (also known as Clarks Hill Lake) 71,100 acres (290 km2)

- Lake Moultrie 60,000 acres (240 km2)

- Lake Hartwell 56,000 acres (230 km2)

- Lake Murray 50,000 acres (200 km2)

- Russell Lake 26,650 acres (110 km2)

- Lake Keowee 18,372 acres (70 km2)

- Lake Wylie 13,400 acres (50 km2)

- Lake Wateree 13,250 acres (50 km2)

- Lake Greenwood 11,400 acres (50 km2)

- Lake Jocassee 7,500 acres (30 km2)

- Lake Bowen 1,534 acres (6.21 km2)

Earthquakes

South Carolina is the most seismically active state on the East Coast.[60] Between July 1, 2021, and July 1, 2022, there were 74 recorded earthquakes in South Carolina,[61] six of which exceeded a 3 magnitude.[62] In 2021 and 2022, most of which were concentrated in Kershaw County and the coastal area of Charleston.[61] The Charleston area demonstrates the greatest frequency of earthquakes in South Carolina. South Carolina averages 10–15 earthquakes a year below magnitude 3 (FEMA). The Charleston earthquake of 1886 was the largest quake ever to hit the eastern United States. The 7.0–7.3 magnitude earthquake killed 60 people and destroyed much of the city.[63] Faults in this region are difficult to study at the surface due to thick sedimentation on top of them. Many of the ancient faults are within plates rather than along plate boundaries.

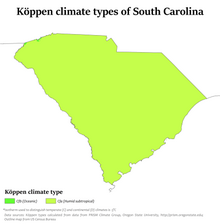

Climate

South Carolina has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), although high-elevation areas in the Upstate area have fewer subtropical characteristics than areas on the Atlantic coastline. In the summer, South Carolina is hot and humid, with daytime temperatures averaging between 86–93 °F (30–34 °C) in most of the state and overnight lows averaging 70–75 °F (21–24 °C) on the coast and from 66–73 °F (19–23 °C) inland. Winter temperatures are much less uniform in South Carolina. Coastal areas of the state have very mild winters, with high temperatures approaching an average of 60 °F (16 °C) and overnight lows around 40 °F (5–8 °C).

Inland, the average January overnight low is around 32 °F (0 °C) in Columbia and temperatures well below freezing in the Upstate. While precipitation is abundant the entire year in almost the entire state, the coast tends to have a slightly wetter summer, while inland, the spring and autumn transitions tend to be the wettest periods and winter the driest season, with November being the driest month. The highest recorded temperature is 113 °F (45 °C) in Johnston and Columbia on June 29, 2012, and the lowest recorded temperature is −19 °F (−28 °C) at Caesars Head on January 21, 1985.

Snowfall in South Carolina is minimal in the lower elevation areas south and east of Columbia. It is not uncommon for areas along the southernmost coast to not receive measurable snowfall for several years. In the Piedmont and Foothills, especially along and north of Interstate 85, measurable snowfall occurs one to three times in most years. Annual average total amounts range from 2 to 6 inches. The Blue Ridge Escarpment receives the most average total measurable snowfall; amounts range from 7 to 12 inches.

South Carolina averages around 50 days of thunderstorm activity a year. This is less than some of the states further south, and it is slightly less vulnerable to tornadoes than the states which border on the Gulf of Mexico. Some notable tornadoes have struck South Carolina, and the state averages around 14 tornadoes annually. Hail is common with many of the thunderstorms in the state, as there is often a marked contrast in temperature of warmer ground conditions compared to the cold air aloft.[64]

Hurricanes and tropical cyclones

The state is occasionally affected by tropical cyclones. This is an annual concern during hurricane season, which lasts from June 1 to November 30. The peak time of vulnerability for the southeast Atlantic coast is from early August to early October, during the Cape Verde hurricane season. Memorable hurricanes to hit South Carolina include Hazel (1954), Hugo (1989), and Florence (2018).

Climate change

Climate change in South Carolina encompasses the effects of climate change, attributed to man-made increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, in the U.S. state of South Carolina.

Studies show that South Carolina is among a string of "Deep South" states that will experience the worst effects of climate change.[65] According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency:

As of January 2020, "South Carolina's failure to develop a comprehensive climate plan means the state has no overall effort to cut greenhouse gas pollution, limit sprawl or educate the public on how to adapt to the changing climate."[67]South Carolina's climate is changing. Most of the state has warmed by one-half to one degree (F) in the last century, and the sea is rising about one to one-and-a-half inches every decade. Higher water levels are eroding beaches, submerging low lands, and exacerbating coastal flooding. Like other southeastern states, South Carolina has warmed less than most of the nation. But in the coming decades, the region's changing climate is likely to reduce crop yields, harm livestock, increase the number of unpleasantly hot days, and increase the risk of heat stroke and other heat-related illnesses.[66]

South Carolina released its Climate, Energy, and Commerce Committee Final Report in 2008. The report recommends a voluntary economy-wide goal of reducing emissions to 5% below 1990 levels by 2020. Key policy recommendations in the report include developing renewable portfolio standards, increasing use of local agricultural products, and increasing advanced recycling and composting.

Federal lands in South Carolina

- Charles Pinckney National Historic Site at Mt. Pleasant

- Congaree National Park in Hopkins

- Cowpens National Battlefield near Chesnee

- Fort Moultrie National Monument at Sullivan's Island

- Fort Sumter National Monument in Charleston Harbor

- Kings Mountain National Military Park at Blacksburg

- Ninety Six National Historic Site in Ninety Six

- Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail

- Fort Jackson near Columbia

- Joint Base Charleston near Charleston

- Shaw Air Force Base near Sumter

- Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island at Parris Island

Flora and fauna

South Carolina is home to two dominant ecosystems, the bottomlands, which consist of floodplains and creeks, and the toplands. The floodplains contain large tracts of old and mature second growth cypress and tupelo forest. The uplands are home to longleaf pine, shortleaf pine, and mixed hardwood forests.[68] The Longleaf Pine are an important part of South Carolina's coastal ecosystem. They improve soil, water, and air quality while providing a habitat for deer and songbirds.[69] These forests are endangered by logging for agriculture and development.[68][70]

Oysters are a critical part of South Carolina's coastal ecology. They serve a dual function, filtering the water and forming reefs that provide a habitat for small fish and crabs. Oysters are imperiled by overharvesting because young oysters need older oysters to latch on to as they age.[70] South Carolina is home to many shorebirds including various sandpipers and ibises.[71][72] The state serves as a stopover site for birds migrating farther south and a wintering ground for birds that do not fly as far south.[72]

Major cities

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Charleston  Columbia |

1 | Charleston | Charleston | 153,672 | 11 | Florence | Florence | 40,072 |  North Charleston  Mount Pleasant |

| 2 | Columbia | Richland | 139,698 | 12 | Spartanburg | Spartanburg | 38,584 | ||

| 3 | North Charleston | Charleston | 118,608 | 13 | Myrtle Beach | Horry | 38,417 | ||

| 4 | Mount Pleasant | Charleston | 94,545 | 14 | Hilton Head Island | Beaufort | 38,069 | ||

| 5 | Rock Hill | York | 75,349 | 15 | Bluffton | Beaufort | 34,493 | ||

| 6 | Greenville | Greenville | 72,310 | 16 | Aiken | Aiken | 32,463 | ||

| 7 | Summerville | Dorchester | 51,617 | 17 | Fort Mill | York | 30,940 | ||

| 8 | Goose Creek | Berkeley | 47,618 | 18 | Anderson | Anderson | 29,771 | ||

| 9 | Sumter | Sumter | 42,757 | 19 | Conway | Horry | 27,346 | ||

| 10 | Greer | Greenville | 42,090 | 20 | Mauldin | Greenville | 26,918 | ||

Statistical areas

The following tables show the major metropolitan and combined statistical areas of South Carolina. Some statistical areas of South Carolina overlap with neighboring states of North Carolina and Georgia.

| Rank | Metropolitan statistical area (MSA) | Population (2023)[6][75] | Counties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC | 2,805,115 | Chester, Lancaster, York |

| 2 | Greenville-Anderson-Greer, SC | 975,480 | Anderson, Greenville, Laurens, Pickens |

| 3 | Columbia, SC | 858,302 | Calhoun, Fairfield, Kershaw, Lexington, Richland, Saluda |

| 4 | Charleston-North Charleston, SC | 849,417 | Berkeley, Charleston, Dorchester |

| 5 | Augusta-Richmond County, GA-SC | 629,429 | Aiken, Edgefield |

| 6 | Myrtle Beach-Conway-North Myrtle Beach, SC | 397,478 | Horry |

| 7 | Spartanburg, SC | 383,327 | Spartanburg |

| 8 | Hilton Head Island-Bluffton-Port Royal, SC | 232,523 | Beaufort, Jasper |

| 9 | Florence, SC | 199,630 | Darlington, Florence |

| 10 | Sumter, SC | 104,165 | Sumter |

| Rank | Combined statistical area (CSA) | Population (2023)[6][75] | Counties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charlotte-Concord, NC-SC | 3,387,115 | Chester, Lancaster, York |

| 2 | Greenville-Spartanburg-Anderson, SC | 1,590,636 | Abbeville, Anderson, Cherokee, Greenville, Laurens, Oconee, Pickens, Spartanburg, Union |

| 3 | Columbia-Sumter-Orangeburg, SC | 1,084,112 | Calhoun, Fairfield, Kershaw, Lexington, Newberry, Orangeburg, Richland, Saluda |

| 5 | Myrtle Beach-Conway, SC | 463,209 | Georgetown, Horry |

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 249,073 | — | |

| 1800 | 345,591 | 38.8% | |

| 1810 | 415,115 | 20.1% | |

| 1820 | 502,741 | 21.1% | |

| 1830 | 581,185 | 15.6% | |

| 1840 | 594,398 | 2.3% | |

| 1850 | 668,507 | 12.5% | |

| 1860 | 703,708 | 5.3% | |

| 1870 | 705,606 | 0.3% | |

| 1880 | 995,577 | 41.1% | |

| 1890 | 1,151,149 | 15.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,340,316 | 16.4% | |

| 1910 | 1,515,400 | 13.1% | |

| 1920 | 1,683,724 | 11.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,738,765 | 3.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,899,804 | 9.3% | |

| 1950 | 2,117,027 | 11.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,382,594 | 12.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,590,516 | 8.7% | |

| 1980 | 3,121,820 | 20.5% | |

| 1990 | 3,486,703 | 11.7% | |

| 2000 | 4,012,012 | 15.1% | |

| 2010 | 4,625,364 | 15.3% | |

| 2020 | 5,118,425 | 10.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 5,373,555 | [2] | 5.0% |

| Source: 1910–2020[76] | |||

| Race and ethnicity[77] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 62.1% | 65.5% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 24.8% | 26.3% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[b] | — | 6.9% | ||

| Asian | 1.7% | 2.3% | ||

| Native American | 0.3% | 1.8% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.4% | 1.0% | ||

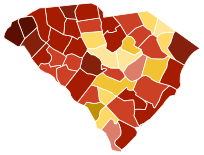

| Non-Hispanic White 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 80–90% | Black or African American 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% |

| Racial composition | 1990[78] | 2000[79] | 2010[80] | 2020[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 69.0% | 67.2% | 66.2% | 63.4% |

| Black | 29.8% | 29.5% | 27.9% | 25.0% |

| Asian | 0.6% | 0.9% | 1.3% | 1.8% |

| Native American | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.0% | 1.7% | 5.8% |

The 2020 census determined the state had a population of 5,118,425, a 10.7% percentage increase since the 2010 census.[82]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 3,608 homeless people in South Carolina.[83][84]

At the 2020 census, the racial make up of the state was 63.4% White (62.1% non-Hispanic white), 25.0% Black or African American, 0.5% American Indian and Alaska Native, 1.8% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 3.5% from some other race, and 5.8% from two or more races. 6.9% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin of any race.[81]

At the 2019 census estimate, South Carolina had an estimated population of 5,148,714, which is an increase of 64,587 from the prior year and an increase of 523,350, or 11.31%, since the year 2010. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 36,401 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 115,084 people. According to the University of South Carolina's Arnold School of Public Health, Consortium for Latino Immigration Studies, South Carolina's foreign-born population grew faster than any other state between 2000 and 2005.[85][86] South Carolina has banned sanctuary cities.[87]

The top countries of origin for South Carolina's immigrants were Mexico, India, Germany, Honduras and the Philippines, as of 2018.[88]

Historical South Carolina racial breakdown of population[89]

Religion

Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[90]

According to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), in 2010, the largest religion is Christianity, of which the largest denominations were the Southern Baptist Convention with 913,763 adherents, the United Methodist Church with 274,111 adherents, and the Roman Catholic Church with 181,743 adherents. Fourth-largest is the African Methodist Episcopal Church with 564 congregations and 121,000 members and fifth-largest is the Presbyterian Church (USA) with 320 congregations and almost 100,000 members.[91] As of 2010, South Carolina was the American state with the highest per capita proportion of citizens who follow the Baháʼí Faith, with 17,559 adherents,[92] making Baháʼí the second-largest religion in the state at the time.[93]

According to the Public Religion Research Institute in 2020, Christianity remained the largest religion at approximately 74% of the population.[94] Among the Christian population, evangelical Protestantism remained the majority; the irreligious community was 18% of the total population. Per ARDA's 2020 religion census, Southern Baptists remained the majority with 816,405 adherents, and Roman Catholics had 407,840 adherents, followed by United Methodists at 242,467. As other Baptist denominations had from 10 to 40,000+ members individually, nondenominational/interdenominational Protestants increased to 454,063 adherents.[95]

Outside of Christianity, ARDA's 2020 study reported 6,677 Muslims in the state, and 830 Orthodox Jews; Reform Judaism consisted of 3,430 adherents. Altogether, Hinduism had 8,383 adherents.[95]

In 2022, the Public Religion Research Institute estimated that Christians increased to 76% of the population (64% Protestant, 11% Catholic, and 1% Jehovah's Witness). The unaffiliated also increased, forming 20% of the state's population, although New Agers constituted 3% of the state. Judaism was 1% of the total population.

Economy

In 2019, South Carolina's GDP was $249.9 billion, making the state the 26th largest by GDP in the United States.[96] According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, South Carolina's gross state product (GSP) was $97 billion in 1997 and $153 billion in 2007. Its per-capita real gross domestic product (GDP) in chained 2000 dollars was $26,772 in 1997 and $28,894 in 2007; which represented 85% of the $31,619 per-capita real GDP for the United States overall in 1997, and 76% of the $38,020 for the U.S. in 2007. The state debt in 2012 was calculated by one source to be $22.9bn, or $7,800 per taxpayer.[97]

Industrial outputs include textile goods, chemical products, paper products, machinery, automobiles, automotive products and tourism. Major agricultural outputs of the state are tobacco, poultry, cotton, cattle, dairy products, soybeans, hay, rice, and swine.[98][99] According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of March 2012, South Carolina had 1,852,700 nonfarm jobs of which 12% are in manufacturing, 11.5% are in leisure and hospitality, 19% are in trade, transportation, and utilities, and 11.8% are in education and health services. The service sector accounts for 83.7% of the South Carolina economy.[100]

Many large corporations have moved their locations to South Carolina. Boeing opened an aircraft manufacturing facility at Charleston International Airport in 2011, which serves as one of two final assembly sites for the 787 Dreamliner. South Carolina is a right-to-work state[101] and many businesses use staffing agencies to temporarily fill positions.[102] Domtar, in Rock Hill, used to be the only Fortune 500 company headquartered in South Carolina, but it was later moved into the Fortune 1000 list.[103][104] The three Fortune 1000 companies headquartered in the state are Domtar, Sonoco Products, and ScanSource.[104]

South Carolina also benefits from foreign investment. There are 1,950 foreign-owned firms operating in South Carolina employing almost 135,000 people.[105] Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) brought 1.06 billion dollars to the state economy in 2010.[106] Since 1994, BMW has had a production facility in Spartanburg County near Greer and since 1996 the Zapp Group operates in Summerville near Charleston.

Transportation and infrastructure

The state has the fourth largest state-maintained highway system in the country, consisting of 11 Interstates, numbered highways, state highways, and secondary roads, totalling approximately 41,500 miles (66,800 km).[107]

On secondary roads, South Carolina uses a numbering system to keep track of all non-interstate and primary highways that the South Carolina Department of Transportation maintains. Secondary roads are numbered by the number of the county followed by a unique number for the particular road.

Major highways

Primary Interstates

Auxiliary (three-digit) Interstates

Rail

South Carolina passenger rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern are the only Class I railroad companies in South Carolina, as other freight companies in the state are short lines.

Amtrak operates four passenger routes in South Carolina: the Crescent, the Palmetto, the Silver Meteor, and the Silver Star. The Crescent route serves the Upstate cities, the Silver Star serves the Midlands cities, and the Palmetto and Silver Meteor routes serve the lowcountry cities.

| Station | Connections |

|---|---|

| Camden | |

| North Charleston | |

| Columbia | |

| Clemson | |

| Denmark | |

| Dillon | |

| Florence | |

| Greenville | |

| Kingstree | |

| Spartanburg | |

| Yemassee |

Major and regional airports

There are seven significant airports in South Carolina, all of which act as regional airport hubs. The busiest by passenger volume is Charleston International Airport.[108] Just across the border in North Carolina is Charlotte/Douglas International Airport, the 30th busiest airport in the world, in terms of passengers.[109]

- Columbia Metropolitan Airport – Columbia

- Charleston International Airport – North Charleston

- Greenville-Spartanburg International Airport – Greenville/Spartanburg

- Florence Regional Airport – Florence

- Myrtle Beach International Airport – Myrtle Beach

- Hilton Head Airport – Hilton Head Island/Beaufort

- Rock Hill/York County Airport – Rock Hill

Education

As of 2010, South Carolina is one of three states that have not agreed to use competitive international math and language standards.[110]

In 2014, the South Carolina Supreme Court ruled the state had failed to provide a "minimally adequate" education to children in all parts of the state as required by the state's constitution.[111]

South Carolina has 1,144 K–12 schools in 85 school districts with an enrollment of 712,244 as of fall 2009.[112][113] As of the 2008–2009 school year, South Carolina spent $9,450 per student which places it 31st in the country for per student spending.[114]

In 2015, the national average SAT score was 1490 and the South Carolina average was 1442, 48 points lower than the national average.[115]

South Carolina is the only state which owns and operates a statewide school bus system. As of December 2016, the state maintains a 5,582-bus fleet with the average vehicle in service being fifteen years old (the national average is six) having logged 236,000 miles.[116] Half of the state's school buses are more than 15 years old and some are reportedly up to 30 years old. In 2017 in the budget proposal, Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman requested the state lease to purchase 1,000 buses to replace the most decrepit vehicles. An additional 175 buses could be purchased immediately through the State Treasurer's master lease program.[117] On January 5, 2017, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency awarded South Carolina more than $1.1 million to replace 57 school buses with new cleaner models through its Diesel Emissions Reduction Act program.[118]

Higher education

South Carolina has diverse institutions from large state-funded research universities to small colleges that cultivate a liberal arts, religious, or military tradition. (List below sorted by year established.)

- The College of Charleston, founded in 1770 and chartered in 1785, is the oldest institution of higher learning in South Carolina, the 13th oldest in the United States, and the first municipal college in the country. The college is in company with the Colonial Colleges as one of the original and foundational institutions of higher education in the United States. Its founders include three signers of the United States Declaration of Independence and three signers of the United States Constitution. The college's historic campus, listed on the U.S. Department of the Interior's National Register of Historic Places, forms an integral part of Charleston's colonial-era urban center. The Graduate School of the College of Charleston offers a number of degree programs and coordinates support for its nationally recognized faculty research efforts.

- The University of South Carolina, in Columbia, is a flagship, public, co-educational, research university with seven satellite campuses. It was founded in 1801 as South Carolina College, and its original campus, The Horseshoe, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The university's main campus covers over 359 acres (1.5 km2) in the urban core less than one city block from the South Carolina State House. The University of South Carolina has around 35,000 students on the Columbia campus.

- Furman University is a private, coeducational, non-sectarian, liberal arts university in Greenville. Founded in 1826, Furman enrolls approximately 2,900 undergraduate and 500 graduate students. Furman is the largest private institution in South Carolina. The university is primarily focused on undergraduate education (only two departments, education and chemistry, offer graduate degrees).

- Erskine College is a private, coeducational liberal arts college in Due West, South Carolina. The college was founded in 1839 and is affiliated with the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, which maintains a theological seminary on the campus.

- The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina is a state-supported, comprehensive college in Charleston. Founded in 1842, it is best known for its undergraduate Corps of Cadets military program for men and women, which combines academics, physical challenges and military discipline. In addition to the cadet program, the Citadel Graduate College offers evening certificate, undergraduate and graduate programs to civilians. The Citadel has 2,200 undergraduate cadets in its residential military program and 1,200 civilian students in the evening programs.

- Wofford College is a small liberal arts college in Spartanburg. Wofford was founded in 1854 with a bequest of $100,000 from the Rev. Benjamin Wofford (1780–1850), a Methodist minister and Spartanburg native who sought to create a college for "literary, classical, and scientific education in my native district of Spartanburg". It is one of the few four-year institutions in the southeastern United States founded before the American Civil War that operates on its original campus.

- Newberry College is a small liberal arts college in Newberry. Founded in 1856, Newberry is a co-educational, private liberal-arts college of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) on a historic 90-acre (36 ha) campus in Newberry, South Carolina. It has roughly 1,110 students and a 14:1 student-teacher ratio. According to U.S. News & World Report's America's Best Colleges, Newberry College ranks among the nation's top colleges in the southern region.

- Claflin University, founded in 1869 by the American Missionary Association, is the oldest historically black college in the state. After the Democratic-dominated legislature closed the university in 1877, before passing a law to restrict admission to whites, it designated Claflin as the only state college for blacks.

- Lander University is a public liberal arts university in Greenwood. Lander was founded in 1872 as Willamston Female College.[119] The school moved to Greenwood in 1904 and was renamed Lander College in honor of its founder, Samuel Lander. In 1973 Lander became part of the state's higher education system and is now a co-educational institution. The university is focused on undergraduate education and enrolls approximately 3,000 undergraduates.

- Presbyterian College (PC) is a private liberal arts college founded in 1880 in Clinton. Presbyterian College enrolls around 1000 undergraduate students and around 200 graduate students in its pharmacy school. In 2007, Washington Monthly ranked PC as the No. 1 Liberal Arts College in the nation.[120]

- Winthrop University, founded in 1886 as an all-female teaching school in Rock Hill, became a co-ed institution in 1974. It is now a public university with an enrollment of just over 6,100 students. It is one of the fastest growing universities in the state, with several new academic and recreational buildings being added to the main campus in the past five years, as well as several more planned for the near future. The Richard W. Riley College of Education is still the school's most well-known area of study.

- Clemson University, founded in 1889, is a public, coeducational, land-grant research university in Clemson. It has more than 19,000 undergraduate students and 5,200 graduate students from all 50 states and from more than 70 countries. Clemson is also the home to the South Carolina Botanical Garden.

- North Greenville University, founded in 1891, is a comprehensive university in Tigerville. It is affiliated with South Carolina Baptist Convention and the Southern Baptist Convention, and is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. It has an enrollment of around 2,500 undergraduates.

- South Carolina State University, founded in 1896, is a historically black university in Orangeburg. SCSU has an enrollment of nearly 5,000, and offers undergraduate, graduate and post-graduate degrees. SCSU boasts the only Doctor of Education program in the state.

- Anderson University, founded in 1911, is a selective comprehensive university that offers bachelor's and master's degrees. It enrolls about 2,900 students.

- Webster University, founded in 1915 in St. Louis, MO, with five extended campuses in SC, offers undergraduate and graduate degrees.

- Bob Jones University, founded in 1927, is a private, non-denominational and conservative Christian liberal arts university with a 2019 total enrollment of 3,000. BJU offers more than 60 undergraduate majors and 70 graduate programs.[121][122]

- Coastal Carolina University, founded in 1954, became an independent state-supported liberal arts university in 1993. The university enrolls approximately 10,500 students on its 307-acre (1.24 km2) campus in Conway, part of the Myrtle Beach metropolitan area. Baccalaureate programs are offered in 51 major fields of study, along with graduate programs in education, business administration (MBA), and coastal marine and wetland studies.

- Charleston Southern University, founded in 1969, is a liberal arts university, and is affiliated with the South Carolina Baptist Convention. Charleston Southern (CSU) is on 300 acres, formerly the site of a rice and indigo plantation, in the city of North Charleston one of South Carolina's largest accredited, independent universities, enrolling approximately 3,400 students.

- Francis Marion University, formerly Francis Marion College, is a state-supported liberal arts university near Florence, South Carolina. It was founded in 1970 and achieved university status in 1992.

Health care

For overall health care, South Carolina is ranked 37th out of the 50 states in 2022, according to The Commonwealth Fund, a private health foundation working to improve the health care system.[123] The state's teen birth rate was 53 births per 1,000 teens, compared to the national average of 41.9 births, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.[124] The state's infant mortality rate was 9.4 deaths per 1,000 births compared to the national average of 6.9 deaths.[125]

There were 2.6 physicians per 1,000 people compared to the national average of 3.2 physicians.[126] There was $5,114 spent on health expenses per capita in the state, compared to the national average of $5,283.[127] There were 26 percent of children and 13 percent of elderly living in poverty in the state, compared to 23 percent and 13 percent, respectively, doing so in the U.S.[128] And, 34 percent of children were overweight or obese, compared to the national average of 32 percent.[129]

Media

There are 36 TV stations (including PBS affiliates) serving South Carolina with terrestrial, and some online streaming access. Markets in which the stations are located include Columbia, Florence, Allendale, Myrtle Beach, Greenville, Charleston, Conway, Beaufort, Hardeeville, Spartanburg, Greenwood, Anderson and Sumter. There are multiple news companies in South Carolina, some major ones are The Charleston Chronicle, Greenville News, The Post and Courier, The State, and The Sun News.

Government and politics

South Carolina's state government consists of executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The governor of South Carolina heads the executive branch; the South Carolina General Assembly heads the legislative branch; and the South Carolina Supreme Court heads the judicial branch.

South Carolina is a largely conservative state. Since the Declaration of Independence, South Carolina's politics have been controlled by three main parties: the Democratic-Republican Party in the early 1800s, the Democratic Party through most of the 19th and 20th centuries, and the Republican Party in the 21st century. Since the mid-1990s, the South Carolina General Assembly has been controlled by the Republican party, and currently, eight of nine statewide offices are held by Republican officeholders and one by a Democratic officeholder.[130][131]

At the federal level, South Carolina has voted Republican in every presidential election since the 1976 election of Jimmy Carter.[132] Both of South Carolina's senators are Republican. The most-recent Democratic senator to serve was Fritz Hollings, who left office in 2005. South Carolina has seven representatives in the United States House of Representatives, six of whom are Republican.

As of November 8, 2022, there were 3,740,743 registered voters.[133] In a 2020 study, South Carolina was ranked by the Election Law Journal as the 7th hardest state for citizens to vote in.[134] South Carolina retains the death penalty. Authorized methods of execution include by electric chair or firing squad.[135]

An April 2023 Winthrop University poll found that an overwhelming majority of South Carolians supported legalizing medical marijuana and believed that a separation between church and state was "critical". A large majority were also found to support same-sex marriage, legalized recreational marijuana and sports gambling, along with an independent commission system for congressional redistricting.[136]

Culture

South Carolina has many venues for visual and performing arts. The Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, the Greenville County Museum of Art, the Columbia Museum of Art, Spartanburg Art Museum, and the South Carolina State Museum in Columbia among others provide access to visual arts to the state. There are also numerous historic sites and museums scattered throughout the state paying homage to many events and periods in the state's history from Native American inhabitation to the present day.

South Carolina also has performing art venues including the Peace Center in Greenville, the Koger Center for the Arts in Columbia, and the Newberry Opera House, among others to bring local, national, and international talent to the stages of South Carolina. Several large venues can house major events, including Colonial Life Arena in Columbia, Bon Secours Wellness Arena in Greenville, and North Charleston Coliseum.

One of the nation's major performing arts festivals, Spoleto Festival USA, is held annually in Charleston. There are also countless local festivals throughout the state highlighting many cultural traditions, historical events, and folklore.

According to the South Carolina Arts Commission, creative industries generate $9.2 billion annually and support over 78,000 jobs in the state.[137] A 2009 statewide poll by the University of South Carolina Institute for Public Service and Policy Research found that 67% of residents had participated in the arts in some form during the past year and on average citizens had participated in the arts 14 times in the previous year.

Sports

Although no major league professional sports teams are based in South Carolina, the Carolina Panthers have training facilities in the state and played their inaugural season's home games at Clemson's Memorial Stadium in 1995. They now play at Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, North Carolina. The Panthers consider themselves "The Carolinas' Team" and refrained from naming themselves after Charlotte or either of the Carolinas. The state is also home to numerous minor league professional teams. College teams represent their particular South Carolina institutions, and are the primary options for football, basketball and baseball attendance in the state. South Carolina is also a top destination for golf and water sports.

South Carolina is also home to one of NASCAR's first tracks and its first paved speedway, Darlington Raceway, located northwest of Florence.

See also

- Index of South Carolina-related articles

- Outline of South Carolina

- Bibliography of South Carolina history

Notes

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ Persons of Hispanic or Latino origin are not distinguished between total and partial ancestry.

References

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "QuickFacts: South Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ "Median Annual Household Income". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Columbia city, South Carolina". Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Charleston city, South Carolina". Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ N. C. Board of Agriculture (1902). A sketch of North Carolina. Charleston: Lucas-Richardson Co. p. 4. OL 6918901M.

- ^ Revolutionary War in South Carolina. Discover South Carolina. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ 2019 Top Industries in South Carolina Archived June 15, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. greerdevelopment.com. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ University Of South Carolina. "New Evidence Puts Man In North America 50,000 Years Ago." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, November 18, 2004.

- ^ a b c d Liefermann, Henry; Horan, Eric (2000). South Carolina (3rd ed.). Oakland, CA: Compass American Guides. pp. 13–47, 252–254. ISBN 978-0-679-00509-4.

- ^ "What type of dwellings did the Cherokee Indians live in?". Reference. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Prince, Danforth (March 10, 2011). Frommer's The Carolinas and Georgia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-118-03341-8. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas D. The Ashley Cooper Plan: The Founding of Carolina and the Origins of Southern Political Culture. Chapter 1.

- ^ a b c Ethridge, R. (2010). From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540–1715. United States: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807899335.

- ^ a b c Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. New York: Yale University Press. p. 299. ISBN 0-300-10193-7.

- ^ a b c d "South Carolina Information: History and Culture". SC State Library. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "The Avalon Project : Constitution of South Carolina – March 26, 1776". Avalon.law.yale.edu. June 30, 1906. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "South Carolina State and Local Government". The Green Papers. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Gordon, John W. (2007). South Carolina and the American Revolution : a battlefield history (Paperback ed.). Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570036613.

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1994, p.73

- ^ Nell Porter Brown, "A 'portion of the People' Archived September 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine", Harvard Magazine, January–February 2003

- ^ "POP Culture: 1800". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "South Carolina Constitution of 1790". Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "H. Rept. 22-1 - South Carolina claims. December 15, 1831". GovInfo.gov. U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ Avery Craven, The Growth of Southern Nationalism, 1848–1861 Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 1953. ISBN 978-0-8071-0006-6, p. 391, 394, 396.

- ^ "Resolution to Call the Election of Abraham Lincoln as U.S. President a Hostile Act, 9 November 1860". Teaching American History in South Carolina. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ a b "Civil War in South Carolina". Palmetto History. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "The Port Royal Experiment (1862–1865)". Virginia Commonwealth University. February 24, 2014. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. p. 375.

- ^ Carey, Liz. (July 5, 2014). The dark corner of South Carolina. Independent Mail. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ Richardson, Heather (March 16, 2018). "South Carolina's Remarkable Democratic Experiment of 1868". We're History. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ "The First South Carolina Legislature After the 1867 Reconstruction Acts". Facing History and Ourselves. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Lawrence Edward Carter. Walking Integrity: Benjamin Elijah Mays, Mentor to Martin Luther King Jr.. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1998, pp. 43–44

- ^ a b c McFeely (1981), Grant: A Biography, pp. 367–374

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p.12 Archived November 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Charlie B. Tyler, "The South Carolina Governance Project" Archived June 29, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, University of South Carolina, 1998, pp. 221–222

- ^ "All Niggers, More or Less!" The News and Courier, Oct. 17 1895, 5

- ^ Joel Williamson, New People: Miscegenation and Mulattoes in the United States (New York, 1980) 93

- ^ Lerone Bennett Jr., Before the Mayflower: A History of Black America, 6th rev. ed. (New York, 1993) 319

- ^ Theodore D. Jervey, The Slave Trade: Slavery and Color (Columbia: The State Company, 1925), p. 199

- ^ "South Carolina: The Decline of Agriculture and the Rise of Jim Crowism" Archived December 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, infoplease (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia), 2012

- ^ Mickey, Robert; Paths Out of Dixie: The Democratization of Authoritarian Enclaves in America's Deep South, 1944–1972, p. 29 ISBN 0691149631

- ^ Edgar, Walter; South Carolina in the Modern Age, pp. 104, 107 ISBN 087249831X

- ^ History and Culture - South Carolina State Library. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Pro Business Environment Archived January 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine SC Department of Commerce, Accessed on May 10, 2012

- ^ Galewitz, Phil (December 8, 2014). "Despite Decline, Elective Early Births Remain A Medicaid Problem". NPR. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Dahlen, Heather M.; McCullough, J. Mac; Fertig, Angela R.; Dowd, Bryan E.; Riley, William J. (March 2017). "Texas Medicaid Payment Reform: Fewer Early Elective Deliveries And Increased Gestational Age And Birthweight". Health Affairs. 36 (3): 460–467. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0910. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 28264947.

- ^ "Non Payment Policy for Deliveries Prior to 39 weeks: Birth Outcomes Initiative | SC DHHS". Archived from the original on December 16, 2012. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ^ WCNC Same-sex marriage begins in South Carolina Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine 2014/11/19

- ^ "Women in State Legislatures for 2022". ncsl.org. National Conference for State Legislatures. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "The Geography of South Carolina". Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ "United States Summary: 2010, Population and Housing Unit Counts, 2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. September 2012. pp. V–2, 1 & 41 (Tables 1 & 18). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c Olson, D. M; E. Dinerstein; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933–938. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Swezey, C.S., Fitzwater, B.A., Whittecar, G.R., Mahan, S.A., Garrity, C.P., Aleman Gonzalez, W.B., and Dobbs, K.M., 2016, "The Carolina Sandhills: Quaternary eolian sand sheets and dunes along the updip margin of the Atlantic Coastal Plain province, southeastern United States": Quaternary Research, v. 86, p. 271-286; www.cambridge.org/core/journals/quaternary-research

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S. Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

- ^ "South Carolina SC – Lakes". Sciway.net. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ^ "Limnological Conditions in Lake William C. Bowen" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Nevin (June 30, 2022). "DHEC answers: Is mining causing the recent earthquakes?". WISTV. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b "Recent Earthquakes". SCDNR Geological Survey. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Recent Earthquakes Near South Carolina, United States". Earthquaketracker.com. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Abridged from Seismicity of the United States, 1568–1989 (Revised), by Carl W. Stover and Jerry L. Coffman, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1527, United States Government Printing Office, Washington: 1993.

- ^ NOAA National Climatic Data Center Archived October 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on October 24, 2006.

- ^ Meyer, Robinson (June 29, 2017). "The American South Will Bear the Worst of Climate Change's Costs". The Atlantic.

- ^ "What Climate Change Means for South Carolina" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. August 2016.

- ^ Fretwell, Sammy (January 26, 2020). "As heat rises, SC watches quietly. Will state suffer from lack of climate action?". The State. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "The "Green Heart of South Carolina" Beats in the Congaree Biosphere Region (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Longleaf Pine Initiative in South Carolina". Natural Resources Conservation Service South Carolina. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "South Carolina Wants You To Recycle Your Empty Oyster Shells". Saveur. April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "White Ibis". South Carolina Public Radio. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "SCDNR - Coastal Birds in South Carolina - Shorebirds". www.dnr.sc.gov. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "USA: South Carolina". City Population. July 1, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "South Carolina Cities by Population". www.southcarolina-demographics.com. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "OMB Bulletin No. 23-01: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. July 21, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Historical Population Change Data (1910–2020)". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Race and Ethnicity in the United States: 2010 Census and 2020 Census". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "Population of South Carolina: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts". Censusviewer.com. Retrieved April 17, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "2010 Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 16, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2020 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): South Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ "QuickFacts South Carolina; UNITED STATES". 2019 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. February 18, 2020. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ "2007-2022 PIT Counts by State".

- ^ "The 2022 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress" (PDF).

- ^ "The Economic and Social Implications of the Growing Latino Population in South Carolina", Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine A Study for the South Carolina Commission for Minority Affairs prepared by The Consortium for Latino Immigration Studies, University of South Carolina, August 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ^ ""Mexican Immigrants: The New Face of the South Carolina Labor Force", Archived October 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Moore School of Business, Division of Research, IMBA Globilization Project, University of South Carolina, March 2006.

- ^ Shoichet, Catherine E. (May 9, 2019). "Florida is about to ban sanctuary cities. At least 11 other states have, too". CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "Immigrants in South Carolina" (PDF). American Immigration Council. 2020.

- ^ Rogers, George C. Jr.; Taylor, C. James (1994). A South Carolina Chronology 1497–1992. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-971-5.

- ^ Staff (February 24, 2023). "American Values Atlas: Religious Tradition in South Carolina". Public Religion Research Institute. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Religious Congregations & Membership Study". Rcms2010.org. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Hawes, Jennifer Berry. "Baha'i infusion Louis G. Gregory was a key Baha'i figure in Charleston". Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ "PRRI – American Values Atlas". ava.prri.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b "Maps and data files for 2020 | U.S. Religion Census | Religious Statistics & Demographics". www.usreligioncensus.org. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ "Regional Data GDP and Personal Income". U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived from the original on June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "The 24th worst state" (PDF). statedatalab.org. Truth in Accounting. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ Gross Domestic Product by State Archived July 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, June 5, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2009.

- ^ Bls.gov Archived July 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ Economy at a Glance South Carolina Archived May 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Accessed on May 10, 2012

- ^ "List of Right To Work States | Right to Work States Meaning". Righttoworkstates.org. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "Staffing Firms Employed 354,400 Workers in South Carolina" (PDF). American Staffing Association. February 8, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ Exxon Mobil Corporation Archived May 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ a b Sam (June 26, 2019). "Can a Fortune 500 company open their headquarters in S.C.?". COLAtoday. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ South Carolina Tennessee Archived May 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ FDI in south Carolina a five year report, Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ "SCDOT: Statewide Transportation Improvement Program" (PDF). South Carolina Department of Transportation. July 16, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ 2007 PRELIMl passenger ranking[dead link]

- ^ "Airports Council International". Aci.aero. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ Hunt, Albert R. (August 23, 2009). "A $5 billion bet on better education". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Click, Carolyne; Hinshaw, Dawn (November 12, 2014). "SC Supreme Court finds for poor districts in 20-year-old school equity suit". The State. Archived from the original on March 31, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ South Carolina – Fast Facts Archived May 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ NEA Rankings and Estimates Page 11 Archived May 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ NEA Rankings and Estimates Page 54 Archived May 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 10, 2012

- ^ "Average SAT Scores By State (US)". LEAP blog. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2016.