Contents

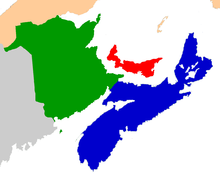

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Canada's population.[1] Together with Canada's easternmost province, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Maritime provinces make up the region of Atlantic Canada.[2]

Located along the Atlantic coast, various aquatic sub-basins are located in the Maritimes, such as the Gulf of Maine and Gulf of St. Lawrence. The region is located northeast of New England in the United States, south and southeast of Quebec's Gaspé Peninsula, and southwest of the island of Newfoundland. The notion of a Maritime Union has been proposed at various times in Canada's history; the first discussions in 1864 at the Charlottetown Conference contributed to Canadian Confederation. This movement formed the larger Dominion of Canada. The Mi'kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy people are indigenous to the Maritimes, while Acadian and British settlements date to the 17th century.

Name

The word maritime is an adjective that means of the sea; thus any land adjacent to the sea can be considered maritime. But the term Maritimes has historically been collectively applied to New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, all of which border the Atlantic Ocean.

History

The pre-history of the Canadian Maritimes begins after the northerly retreat of glaciers at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation over 10,000 years ago; human settlement by First Nations began in the Maritimes with Paleo-Indians during the Early Period, ending around 6,000 years ago.

The Middle Period, starting 6,000 years ago, and ending 3,000 years ago, was dominated by rising sea levels from the melting glaciers in polar regions. This is also when what is called the Laurentian tradition started among Archaic Indians, the term used for First Nations peoples of the time. Evidence of Archaic Indian burial mounds and other ceremonial sites existing in the Saint John River valley has been uncovered.

The Late Period extended from 3,000 years ago until first contact with European settlers. This period was dominated by the organization of First Nations peoples into the Algonquian-speaking Abenaki Nation, which occupied territory largely in present-day interior Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, and the Mi'kmaq Nation, which inhabited all of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, eastern New Brunswick and the southern Gaspé. The primarily agrarian Maliseet Nation settled throughout the Saint John River and Allagash River valleys of present-day New Brunswick and Maine. The Passamaquoddy Nation inhabited the northwestern coastal regions of the present-day Bay of Fundy. The Mi'kmaq Nation is also believed to have crossed the present-day Cabot Strait at around this time to settle on the south coast of Newfoundland, but they were a minority compared to the Beothuk Nation.

European contact

After Newfoundland, the Maritimes were the second area in Canada to be settled by Europeans. There is evidence that Viking explorers discovered and settled in the Vinland region around 1000 AD, which is when the L'Anse aux Meadows settlement in Newfoundland and Labrador has been dated. They may have made further exploration into the present-day Maritimes and northeastern United States.

Both Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) and Giovanni da Verrazzano are reported to have sailed in or near Maritime waters during their voyages of discovery for England and France, respectively.[citation needed] Several Portuguese explorers / cartographers have also documented various parts of the Maritimes, namely Diogo Homem. However, it was French explorer Jacques Cartier who made the first detailed reconnaissance of the region for a European power and, in so doing, claimed the region for the King of France. Cartier was followed by nobleman Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, who was accompanied by explorer / cartographer Samuel de Champlain in a 1604 expedition. During this they established the second permanent European settlement in what is now the United States and Canada, following Spain's settlement at St. Augustine in present-day Florida in the American South. Champlain's settlement at Saint Croix Island, later moved to Port Royal (Annapolis Royal), survived. By contrast, the ill-fated English settlement at Roanoke Colony off the southern American coast did not. The French settlement pre-dated the more successful English settlement at Jamestown in present-day Virginia by three years. Champlain was considered the founder of New France's province of Canada, which comprises much of the present-day lower St. Lawrence River valley in the province of Quebec.

Acadia

Champlain's success in the region, which came to be called Acadie, led to the fertile tidal marshes surrounding the southeastern and northeastern reaches of the Bay of Fundy being populated by French immigrants who called themselves Acadien. The Acadians eventually built small settlements throughout what is today mainland Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, as well as Île-Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island), Île-Royale (Cape Breton Island), and other shorelines of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in present-day Newfoundland and Labrador, and Quebec. Acadian settlements had primarily agrarian economies. Early examples of Acadian fishing settlements developed in southwestern Nova Scotia and in Île-Royale, as well as along the south and west coasts of Newfoundland, the Gaspé Peninsula, and the present-day Côte-Nord region of Quebec. Most Acadian fishing activities were overshadowed by the much larger seasonal European fishing fleets that were based out of Newfoundland and took advantage of proximity to the Grand Banks.

The growing English colonies along the American seaboard to the south and various European wars between England and France during the 17th and 18th centuries brought Acadia to the centre of world-scale geopolitical forces. In 1613, Virginian raiders captured Port-Royal, and in 1621 France ceded Acadia to Scotland's Sir William Alexander, who renamed it as Nova Scotia.

By 1632, Acadia was returned from Scotland to France under the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The Port Royale settlement was moved to the site of nearby present-day Annapolis Royal. More French immigrant settlers, primarily from the Brittany, Normandie, and Vienne regions of France, continued to populate the colony of Acadia during the latter part of the 17th and early part of the 18th centuries. Important settlements also began in the Beaubassin region of the present-day Isthmus of Chignecto, and in the Saint John River valley, as well as smaller communities on Île-Saint-Jean and Île-Royale.

In 1654, raiders from New England attacked Acadian settlements on the Annapolis Basin. Acadians lived with uncertainty throughout the English constitutional crises under Oliver Cromwell, and it was not until the Treaty of Breda in 1667 that France's claim to the region was reaffirmed. Colonial administration by France throughout the history of Acadia was of low priority. France's priorities were in settling and strengthening its claim on the larger territory of New France and the exploration and settlement of interior North America and the Mississippi River valley.

Colonial wars

Over 74 years (1689–1763) there were six colonial wars, which involved continuous warfare between New England and Acadia (see the French and Indian Wars reflecting English and French tensions in Europe, as well as Father Rale's War (Dummer's War) and Father Le Loutre's War). Throughout these wars, New England was allied with the Iroquois Confederacy based around the southern Great Lakes and west of the Hudson River. Acadian settlers were allied with the Wabanaki Confederacy. In the first war, King William's War (the North American theatre of the Nine Years' War), natives from the Maritime region participated in numerous attacks with the French on the Acadia / New England border in southern Maine (e.g., Raid on Salmon Falls). New England retaliatory raids on Acadia, such as the Raid on Chignecto, were conducted by Benjamin Church. In the second war, Queen Anne's War (the North American theatre of the War of the Spanish Succession), the British conducted the Conquest of Acadia, while the region remained primarily in control of Maliseet militia, Acadia militia and Mi'kmaw militia.

In 1719, to further protect strategic interests in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and St. Lawrence River, France began the 20-year construction of a large fortress at Louisbourg on Île-Royale. Massachusetts was increasingly concerned over reports of the capabilities of this fortress, and of privateers staging out of its harbour to raid New England fishermen on the Grand Banks. In the fourth war, King George's War (the North American theatre of the War of the Austrian Succession), the British engaged successfully in the Siege of Louisbourg. The British returned control of Île-Royale to France with the fortress virtually intact three years later under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and the French reestablished their forces there.

In 1749, to counter the rising threat of Louisbourg, Halifax was founded and the Royal Navy established a major naval base and citadel. The founding of Halifax sparked Father Le Loutre's War.

During the sixth and final colonial war, the French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War), the military conflicts in Nova Scotia continued. The British Conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years, the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.[3] The British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians posed and to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia.[4]

The British began the Expulsion of the Acadians with the Bay of Fundy campaign in 1775. Over the next nine years over 12,000 Acadians of 15,000 were removed from Nova Scotia.[5]

In 1758, the fortress of Louisbourg was laid siege for a second time within 15 years, this time by more than 27,000 British soldiers and sailors with over 150 warships. After the French surrender, Louisbourg was thoroughly destroyed by British engineers to ensure it would never be reclaimed. With the fall of Louisbourg, French and Mi'kmaw resistance in the region crumbled. British forces seized remaining French control over Acadia in the coming months, with Île-Saint-Jean falling in 1759 to British forces on their way to Quebec City for the first siege of Quebec and the ensuing Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

The war ended and Britain had gained control over the entire Maritime region and the Indigenous people signed the Halifax Treaties.

American Revolution

Following the Seven Years' War, empty Acadian lands were settled first by 8,000 New England Planters and then by immigrants brought from Yorkshire. Île-Royale was renamed Cape Breton Island and incorporated into the Colony of Nova Scotia. Some of the Acadians who had been deported came back but went to the eastern coasts of New Brunswick.

Both the colonies of Nova Scotia (present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) and St. John's Island (Prince Edward Island) were affected by the American Revolutionary War, largely by privateering against American shipping, but several coastal communities were also the targets of American raiders. Charlottetown, the capital of the new colony of St. John's Island, was ransacked in 1775 with the provincial secretary kidnapped and the Great Seal stolen. The largest military action in the Maritimes during the revolutionary war was the attack on Fort Cumberland (the renamed Fort Beauséjour) in 1776 by a force of American sympathizers led by Jonathan Eddy. The fort was partially overrun after a month-long siege, but the attackers were ultimately repelled after the arrival of British reinforcements from Halifax.

The most significant impact from this war was the settling of large numbers of Loyalist refugees in the region (34,000 to the 17,000 settlers already there), especially in Shelburne and Parrtown (Saint John). Following the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Loyalist settlers in what would become New Brunswick persuaded British administrators to split the Colony of Nova Scotia to create the new colony of New Brunswick in 1784. At the same time, another part of the Colony of Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, was split off to become the Colony of Cape Breton Island. The Colony of St. John's Island was renamed to Prince Edward Island on November 29, 1798.

The War of 1812 had some effect on the shipping industry in the Maritime colonies of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Cape Breton Island; however, the significant Royal Navy presence in Halifax and other ports in the region prevented any serious attempts by American raiders. Maritime and American privateers targeted unprotected shipping of both the United States and Britain respectively, further reducing trade. New Brunswick's section of the Canada–US border did not have any significant action during this conflict, although British forces did occupy a portion of coastal Maine at one point. The most significant incident from this war which occurred in the Maritimes was the British capture and detention of USS Chesapeake, an American frigate in Halifax.

19th century

In 1820, the Colony of Cape Breton Island was merged back into the Colony of Nova Scotia for the second time by the British government.

British settlement of the Maritimes, as the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island came to be known, accelerated throughout the late 18th century and into the 19th century with significant immigration to the region as a result of Scottish migrants displaced by the Highland Clearances and Irish escaping the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849). As a result, significant portions of the three provinces are influenced by Celtic heritages, with Scottish Gaelic (and to a lesser degree, Irish Gaelic) having been widely spoken, particularly in Cape Breton, although it is less prevalent today.

During the American Civil War, a significant number of Maritimers volunteered to fight for the armies of the Union, while a small handful joined the Confederate Army. However, the majority of the conflict's impact was felt in the shipping industry. Maritime shipping boomed during the war due to large-scale Northern imports of war supplies which were often carried by Maritime ships as Union ships were vulnerable to Confederate naval raiders. Diplomatic tensions between Britain and the Unionist North had deteriorated after some interests in Britain expressed support for the secessionist Confederate South. The Union Navy, although much smaller than the British Royal Navy and no threat to the Maritimes, did posture off Maritime coasts at times chasing Confederate naval ships which sought repairs and reprovisioning in Maritime ports, especially Halifax.

The immense size of the Union Army (the largest on the planet toward the end of the Civil War), however, was viewed with increasing concern by Maritimers throughout the early 1860s. Another concern was the rising threat of Fenian raids on border communities in New Brunswick by the Fenian Brotherhood seeking to end British rule in Ireland. This combination of events, coupled with an ongoing decline in British military and economic support to the region as the Home Office favoured newer colonial endeavours in Africa and elsewhere, led to a call among Maritime politicians for a conference on Maritime Union, to be held in early September 1864 in Charlottetown – chosen in part because of Prince Edward Island's reluctance to give up its jurisdictional sovereignty in favour of uniting with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia into a single colony. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia felt that if the union conference were held in Charlottetown, they might be able to convince Island politicians to support the proposal.

The Charlottetown Conference, as it came to be called, was also attended by a slew of visiting delegates from the neighbouring Crown colony, the Province of Canada, who had largely arrived at their own invitation with their own agenda. This agenda saw the conference dominated by discussions of creating an even larger union of the entire territory of British North America into a united colony. The Charlottetown Conference ended with an agreement to meet the following month in Quebec City, where more formal discussions ensued, culminating with meetings in London and the signing of the British North America Act, 1867 (BNA Act). Of the Maritime provinces, only Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were initially party to the BNA Act: Prince Edward Island's reluctance, combined with a booming agricultural and fishing export economy having led to that colony opting not to sign on.

Major population centres

The major communities of the region include Halifax and Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, Moncton, Saint John, and Fredericton in New Brunswick, and Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island.

Climate

In spite of its name, The Maritimes has a humid continental climate of the warm-summer subtype. Especially in coastal Nova Scotia, differences between summers and winters are narrow compared to the rest of Canada. The inland climate of New Brunswick is in stark contrast during winter, resembling more continental areas. Summers are somewhat tempered by the marine influence throughout the provinces, but due to the southerly parallels still remain similar to more continental areas further west. Yarmouth in Nova Scotia has significant marine influence to have a borderline oceanic microclimate, but winter nights are still cold even in all coastal areas. The northernmost areas of New Brunswick are only just above subarctic with very cold continental winters.

| Location | Province | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halifax | Nova Scotia | 23 / 14 | 73 / 57 | 0 / −8 | 32 / 18 |

| Sydney | Nova Scotia | 23 / 12 | 73 / 54 | −1 / −9 | 30 / 16 |

| Fredericton | New Brunswick | 25 / 13 | 77 / 55 | −4 / −15 | 25 / 5 |

| Saint John | New Brunswick | 22 / 11 | 72 / 52 | −2 / −13 | 28 / 9 |

| Moncton | New Brunswick | 24 / 13 | 75 / 55 | −3 / −14 | 27 / 7 |

| Charlottetown | Prince Edward Island | 23 / 14 | 73 / 57 | −3 / −12 | 27 / 10 |

| Yarmouth | Nova Scotia | 21 / 12 | 70 / 54 | 1 / −7 | 34 / 19 |

| Campbellton | New Brunswick | 23 / 10 | 73 / 50 | −9 / −20 | 16 / −4 |

| Greenwood | Nova Scotia | 26 / 14 | 79 / 57 | −1 / −10 | 30 / 14 |

Demographics

The Maritimes were predominantly rural until recent decades, having resource-based economies of fishing, agriculture, forestry, and coal mining.

Maritimers are predominantly of west European origin: Scottish Canadians, Irish Canadians, English Canadians, and Acadians. New Brunswick, in general, differs from the other two Maritime provinces in that it has a much higher Francophone population. There was once a significant Canadian Gaelic speaking population. Helen Creighton recorded Celtic traditions of rural Nova Scotia in the mid-1900s.

There are Black Canadians who are mostly descendants of Black Loyalists or black refugees from the War of 1812. This Maritime population is mainly among Black Nova Scotians.

There are Mi'kmaq reserves in all three provinces, and a smaller population of the Maliseet in western New Brunswick.

Economy

Present status

Given the small population of the region (compared with the Central Canadian provinces or the New England states), the regional economy is a net exporter of natural resources, manufactured goods, and services. The regional economy has long been tied to natural resources such as fishing, logging, farming, and mining activities. Significant industrialization in the second half of the 19th century brought steel to Trenton, Nova Scotia, and subsequent creation of a widespread industrial base to take advantage of the region's large underground coal deposits. After Confederation, however, this industrial base withered with technological change, and trading links to Europe and the U.S. were reduced in favour of those with Ontario and Quebec. In recent years, however, the Maritime regional economy has begun increased contributions from manufacturing again and the steady transition to a service economy.

Important manufacturing centres in the region include Pictou County, Truro, the Annapolis Valley and the South Shore, and the Strait of Canso area in Nova Scotia, as well as Summerside in Prince Edward Island, and the Miramichi area, the North Shore and the upper Saint John River valley of New Brunswick.

Some predominantly coastal areas have become major tourist centres, such as parts of Prince Edward Island, Cape Breton Island, the South Shore of Nova Scotia and the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Bay of Fundy coasts of New Brunswick. Additional service-related industries in information technology, pharmaceuticals, insurance and financial sectors—as well as research-related spin-offs from the region's numerous universities and colleges—are significant economic contributors.

Another important contribution to Nova Scotia's provincial economy is through spin-offs and royalties relating to off-shore petroleum exploration and development. Mostly concentrated on the continental shelf of the province's Atlantic coast in the vicinity of Sable Island, exploration activities began in the 1960s and resulted in the first commercial production field for oil beginning in the 1980s. Natural gas was also discovered in the 1980s during exploration work, and this is being commercially recovered, beginning in the late 1990s. Initial optimism in Nova Scotia about the potential of off-shore resources appears to have diminished with the lack of new discoveries, although exploration work continues and is moving farther off-shore into waters on the continental margin.

Regional transportation networks have also changed significantly in recent decades with port modernizations, with new freeway and ongoing arterial highway construction, the abandonment of various low-capacity railway branch lines (including the entire railway system of Prince Edward Island and southwestern Nova Scotia), and the construction of the Canso Causeway and the Confederation Bridge. There have been airport improvements at various centres providing improved connections to markets and destinations in the rest of North America and overseas.

Improvements in infrastructure and the regional economy notwithstanding, the three provinces remain one of the poorer regions of Canada. While urban areas are growing and thriving, economic adjustments have been harsh in rural and resource-dependent communities, and emigration has been an ongoing phenomenon for some parts of the region. Another problem is seen in the lower average wages and family incomes within the region. Property values are depressed, resulting in a smaller tax base for these three provinces, particularly when compared with the national average which benefits from central and western Canadian economic growth.

This has been particularly problematic with the growth of the welfare state in Canada since the 1950s, resulting in the need to draw upon equalization payments to provide nationally mandated social services. Since the 1990s the region has experienced an exceptionally tumultuous period in its regional economy with the collapse of large portions of the ground fishery throughout Atlantic Canada, the closing of coal mines and a steel mill on Cape Breton Island, and the closure of military bases in all three provinces. That being said, New Brunswick has one of the largest military bases in the Commonwealth of Nations (CFB Gagetown), which plays a significant role in the cultural and economic spheres of Fredericton, the province's capital city.

Historical

Growth

While the economic underperformance of the Maritime economy has been long lasting, it has not always been present. The mid-19th century, especially the 1850s and 1860s, has long been seen as a "Golden Age" in the Maritimes. Growth was strong, and the region had one of British North America's most extensive manufacturing sectors as well as a large international shipping industry. The question of why the Maritimes fell from being a centre of Canadian manufacturing to being an economic hinterland is thus a central one to the study of the region's pecuniary difficulties. The period in which the decline occurred had a great many potential culprits. In 1867 Nova Scotia and New Brunswick merged with the Canadas in Confederation, with Prince Edward Island joining them six years later in 1873. Canada was formed only a year after free trade with the United States (in the form of the Reciprocity Treaty) had ended. In the 1870s John A. Macdonald's National Policy was implemented, creating a system of protective tariffs around the new nation. Throughout the period there was also significant technological change both in the production and transportation of goods.

Reputed Golden Age

Several scholars have explored the so-called "Golden Age" of the Maritimes in the years just before Confederation. In Nova Scotia, the population grew steadily from 277,000 in 1851 to 388,000 in 1871, mostly from natural increase since immigration was slight. The era has been called a Golden Age, but that was a myth created in the 1930s to lure tourists to a romantic era of tall ships and antiques.[7] Recent historians using census data have shown that is a fallacy. In 1851–1871 there was an overall increase in per capita wealth holding. However most of the gains went to the urban elite class, especially businessmen and financiers living in Halifax. The wealth held by the top 10% rose considerably over the two decades, but there was little improvement in the wealth levels in rural areas, which comprised the great majority of the population.[8] Likewise Gwyn reports that gentlemen, merchants, bankers, colliery owners, shipowners, shipbuilders, and master mariners flourished. However the great majority of families were headed by farmers, fishermen, craftsmen and labourer. Most of them—and many widows as well—lived in poverty. Out migration became an increasingly necessary option.[9][10] Thus the era was indeed a golden age but only for a small but powerful and highly visible elite.

Economic decline

The cause of economic malaise in the Maritimes is an issue of great debate and controversy among historians, economists, and geographers. The differing opinions can approximately be divided into the "structuralists", who argue that poor policy decisions are to blame, and the others, who argue that unavoidable technological and geographical factors caused the decline.

The exact date that the Maritimes began to fall behind the rest of Canada is difficult to determine. Historian Kris Inwood places the date very early, at least in Nova Scotia, finding clear signs that the Maritimes "Golden Age" of the mid-19th century was over by 1870, before Confederation or the National Policy could have had any significant impact. Richard Caves places the date closer to 1885. T.W. Acheson takes a similar view and provides considerable evidence that the early 1880s were in fact a booming period in Nova Scotia and this growth was only undermined towards the end of that decade. David Alexander argues that any earlier declines were simply part of the global Long Depression, and that the Maritimes first fell behind the rest of Canada when the great boom period of the early 20th century had little effect on the region. E.R. Forbes, however, emphasizes that the precipitous decline did not occur until after the First World War during the 1920s when new railway policies were implemented. Forbes also contends that significant Canadian defence spending during the Second World War favoured powerful political interests in Central Canada such as C. D. Howe, when major Maritime shipyards and factories, as well as Canada's largest steel mill, located in Cape Breton Island, fared poorly.

One of the most important changes, and one that almost certainly had an effect, was the revolution in transportation that occurred at this time. The Maritimes were connected to central Canada by the Intercolonial Railway in the 1870s, removing a longstanding barrier to trade. For the first time this placed the Maritime manufacturers in direct competition with those of Central Canada. Maritime trading patterns shifted considerably from mainly trading with New England, Britain, and the Caribbean, to being focused on commerce with the Canadian interior, enforced by the federal government's tariff policies.

Coincident with the construction of railways in the region, the age of the wooden sailing ship began to come to an end, being replaced by larger and faster steel steamships. The Maritimes had long been a centre for shipbuilding, and this industry was hurt by the change. The larger ships were also less likely to call on the smaller population centres such as Saint John and Halifax, preferring to travel to cities like New York and Montreal. Even the Cunard Line, founded by Maritime-born Samuel Cunard, stopped making more than a single ceremonial voyage to Halifax each year.

More controversial than the role of technology is the argument over the role of politics in the origins of the region's decline. Confederation and the tariff and railway freight policies that followed have often been blamed for having a deleterious effect on the Maritime economies. Arguments have been made that the Maritimes' poverty was caused by control over policy by Central Canada which used the national structures for its own enrichment. This was the central view of the Maritime Rights Movement of the 1920s, which advocated greater local control over the region's finances. T.W. Acheson is one of the main proponents of this theory. He notes the growth that was occurring during the early years of the National Policy in Nova Scotia demonstrates how the effects of railway fares and the tariff structure helped undermine this growth. Capitalists from Central Canada purchased the factories and industries of the Maritimes from their bankrupt local owners and proceeded to close down many of them, consolidating the industry in Central Canada.

The policies in the early years of Confederation were designed by Central Canadian interests, and they reflected the needs of that region. The unified Canadian market and the introduction of railroads created a relative weakness in the Maritime economies. Central to this concept, according to Acheson, was the lack of metropolises in the Maritimes.

Montreal and Toronto were well-suited to benefit from the development of large-scale manufacturing and extensive railway systems in Quebec and Ontario, these being the goals of the Macdonald and Laurier governments. In the Maritimes the situation was very different. Today New Brunswick has several mid-sized centres in Saint John, Moncton, and Fredericton but no significant population centre. Nova Scotia has a growing metropolitan area surrounding Halifax, but a contracting population in industrial Cape Breton County, and several smaller centres in Bridgewater, Kentville, Yarmouth, and Pictou County. Prince Edward Island's only significant population centres are in Charlottetown and Summerside. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, just the opposite was the case with little to no population concentration in major industrial centres as the predominantly rural resource-dependent Maritime economy continued on the same path as it had since European settlement on the region's shores.

Despite the region's absence of economic growth on the same scale as other parts of the nation, the Maritimes has changed markedly throughout the 20th century, partly as a result of global and national economic trends, and partly as a result of government intervention. Each sub-region within the Maritimes has developed over time to exploit different resources and expertise. Saint John became a centre of the timber trade and shipbuilding and is currently a centre for oil refining and some manufacturing. The northern New Brunswick communities of Edmundston, Campbellton, Dalhousie, Bathurst, and Miramichi are focused on the pulp and paper industry and some mining activity. Moncton was a centre for railways and has changed its focus to becoming a multi-modal transportation centre with associated manufacturing and retail interests. The Halifax metropolitan area has come to dominate peninsular Nova Scotia as a retail and service centre, but that province's industries were spread out from the coal and steel industries of industrial Cape Breton and Pictou counties, the mixed farming of the North Shore and Annapolis Valley, and the fishing industry was primarily focused on the South Shore and Eastern Shore. Prince Edward Island is largely dominated by farming, fishing, and tourism.

Given the geographic diversity of the various sub-regions within the Maritimes, policies to centralize the population and economy were not initially successful, thus Maritime factories closed while those in Ontario and Quebec prospered.

The traditional staples thesis, advocated by scholars such as S.A. Saunders, looks at the resource endowments of the Maritimes and argues that it was the decline of the traditional industries of shipbuilding and fishing that led to Maritime poverty, since these processes were rooted in geography, and thus all but inevitable. Kris Inwood has revived the staples approach and looks at a number of geographic weaknesses relative to Central Canada. He repeats Acheson's argument that the region lacks major urban centres, but adds that the Maritimes were also lacking the great rivers that led to the cheap and abundant hydro-electric power, key to Quebec and Ontario's urban and manufacturing development, that the extraction costs of Maritime resources were higher (particularly in the case of Cape Breton coal), and that the soils of the region were poorer and thus the agricultural sector weaker.

The Maritimes are the only provinces in Canada which entered Confederation in the 19th century and have kept their original colonial boundaries. All three provinces have the smallest land base in the country and have been forced to make do with resources within. By comparison, the former colony of the Province of Canada (divided into the District of Canada East, and the District of Canada West) and the western provinces were dozens of times larger and in some cases were expanded to take in territory formerly held in British Crown grants to companies such as the Hudson's Bay Company; in particular the November 19, 1869 sale of Rupert's Land to the Government of Canada under the Rupert's Land Act 1868 was facilitated in part by Maritime taxpayers. The economic riches of energy and natural resources held within this larger land base were only realized by other provinces during the 20th century.

Industries

The maritime provinces' main industry is fishing. Fishing can be found in any maritime province. This includes fishing for lobster, mackerel, tuna, salmon and many more kinds of fish. Oysters and salmonoid aquaculture is also increasingly important economically.

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is very strong in agriculture, forestry and fishing.

Prince Edward Island

Tourism is important to the economy of PEI. Anne of Green Gables was written in PEI, and this attracts tourists to PEI. PEI is also known for its agriculture, mainly the potato, and fishing industries.

New Brunswick

Agriculture and forestry are two prominent industries found in New Brunswick. Despite having an extensive coastline, New Brunswick's industrial sector has never been entirely reliant on the success of the fisheries. Likewise, the strong shipbuilding heritage of the province directly relates to its forest resources. Because of this, New Brunswickers tend to attribute their cultural heritage less with the sea and more with their forests and rivers.

Politics

Maritime conservatism since the Second World War has been very much part of the Red Tory tradition, key influences being former Premier of Nova Scotia and federal Progressive Conservative Party leader Robert Stanfield and New Brunswick Tory strategist Dalton Camp.

In recent years, the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) has made significant inroads both federally and provincially in the region. The NDP has elected members of parliament (MPs) from New Brunswick, but most of the focus of the party at the federal and provincial levels is currently in the Halifax area of Nova Scotia. Industrial Cape Breton has historically been a region of labour activism, electing Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (and later NDP) MPs, and even produced many early members of the Communist Party of Canada in the pre-Second World War era. In the 2004 federal election, the NDP captured 28.45% of the vote in Nova Scotia, more than any other province. In the 2009 provincial election the NDP formed a majority government, the first in the region.

In the 2004 federal election, the Conservatives had one of the worst showings in the region for a right-wing party, going back to Confederation, with the exception of the 1993 election. The Conservative party improved its seat count in the 2008 and elected 13 MPs in the 2011 election. However, in the 2015 election the Liberal Party won every seat in the region, defeating all of the Conservative (and NDP) challengers.

The Liberal Party of Canada has done well in the Maritimes in the past because of its interventionist policies. The Acadian Peninsula region of New Brunswick tends to vote for the Liberals or NDP for social political reasons, as well as treatment of the French by various parties. In the 1997 federal election, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien's Liberals endured a bitter defeat to the PCs and NDP in many ridings as a result of unpopular cuts to unemployment benefits for seasonal workers, as well as closures of several Canadian Forces bases, the refusal to honour a promise to rescind the Goods and Services Tax, cutbacks to provincial equalization payments, health care, post-secondary education and regional transportation infrastructure such as airports, fishing harbours, seaports, and railways [citation needed]. The Liberals held onto seats in Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick, while being shut out of Nova Scotia entirely, the second time in history (the only other time being the Diefenbaker sweep). In 2015 the Liberals won every seat in The Maritimes, defeating Conservative and NDP incumbents.

The Maritimes is currently represented in the Canadian Parliament by 25 Members of the House of Commons (Nova Scotia – 11, New Brunswick – 10, Prince Edward Island – 4) and 24 Senators (Nova Scotia and New Brunswick – 10 each, Prince Edward Island – 4). This level of representation was established at the time of Confederation when the Maritimes had a much larger proportion of the national population. The comparatively large population growth of western and central Canada during the immigration boom of the 20th century has reduced the Maritimes' proportion of the national population to less than 10%, resulting in an over-representation in Parliament, with some federal ridings having fewer than 35,000 people, compared to central and western Canada where ridings typically contain 100,000–120,000 people.

The Senate of Canada is structured along regional lines, giving an equal number of seats (24) to the Maritimes, Ontario, Quebec, and western Canada, in addition to the later entry of Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as the three territories. Enshrined in the Constitution, this model was developed to ensure that no area of the country is able to exert undue influence in the Senate. The Maritimes, with its much smaller proportion of the national population (compared to the time of Confederation) also have an over-representation in the Senate, particularly compared to the population growth of Ontario and the western provinces. This has led to calls to reform the Senate; however, such a move would entail constitutional changes.

Another factor related to the number of Senate seats is that a constitutional amendment in the early 20th century mandated that no province can have fewer Members of Parliament than it has senators. This court decision resulted from a complaint by the Government of Prince Edward Island after that province's number of MPs was proposed to change from 4 to 3, accounting for its declining proportion of the national population at that time. When PEI entered Confederation in 1873, it was accorded 6 MPs and 4 Senators; however this was reduced to 4 MPs by the early 20th century. Senators being appointed for life at this time, these coveted seats rarely went unfilled for a long period of time anywhere in Canada. As a result, PEI's challenge was accepted by the federal government, and its level of federal representation was secured. In the aftermath of the 1989 budget, which saw a filibuster by Liberal Senators in attempt to kill legislation creating the Goods and Services Tax, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney "stacked" the Senate by creating additional seats in several provinces across Canada, including New Brunswick; however, there was no attempt by these provinces to increase the number of MPs to reflect this change in Senate representation.

See also

- Acadiensis, scholarly history journal covering Atlantic Canada

- Maritime Film Classification Board

- Maritime Quebec

- Maritime Archaic

References

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, 2021 Census". February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Introduction - Atlantic Canada". February 12, 2010.

- ^ John Grenier, Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710–1760. Oklahoma Press. 2008

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction". In P.A. Buckner; Gail G. Campbell; David Frank (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation (3rd ed.). Acadiensis Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1.

• Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm. - ^ Ronnie-Gilles LeBlanc (2005). Du Grand Dérangement à la Déportation: Nouvelles Perspectives Historiques, Moncton: Université de Moncton, 465 pages ISBN 1-897214-02-2 (book in French and English). The Acadians were scattered across the Atlantic, in the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana, Quebec, Britain and France. (See Jean-François Mouhot (2009) Les Réfugiés acadiens en France (1758–1785): L'Impossible Réintégration?, Quebec, Septentrion, 456 p. ISBN 2-89448-513-1; Ernest Martin (1936) Les Exilés Acadiens en France et leur établissement dans le Poitou, Paris, Hachette, 1936). Very few eventually returned to Nova Scotia (See John Mack Faragher (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from their American Homeland, New York: W.W. Norton, 562 pages ISBN 0-393-05135-8 online excerpt).

- ^ "National Climate Data and Information Archive". Environment Canada. October 31, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Ian McKay, "History and the Tourist Gaze: The Politics of Commemoration in Nova Scotia, 1935–1964", Acadiensis, Spring 1993, Vol. 22 Issue 2, pp 102–138

- ^ Julian Gwyn and Fazley Siddiq, "Wealth distribution in Nova Scotia during the Confederation era, 1851 and 1871", Canadian Historical Review, December 1992, Vol. 73 Issue 4, pp 435–52

- ^ Julian Gwyn, "Golden Age or Bronze Moment? Wealth and Poverty in Nova Scotia: The 1850s and 1860s", Canadian Papers in Rural History, 1992, Vol. 8, pp 195–230

- ^ Rural poverty is the theme of Rusty Bittermann, Robert A. Mackinnon, and Graeme Wynn, "Of inequality and interdependence in the Nova Scotian countryside, 1850–70", Canadian Historical Review, March 1993, Vol. 74 Issue 1, pp 1–43