Contents

The 1924 United States presidential election was the 35th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 4, 1924. In a three-way contest, incumbent Republican President Calvin Coolidge won election to a full term. Coolidge was the second vice president to ascend to the presidency and then win a full term.

Coolidge had been vice president under Warren G. Harding and became president in 1923 upon Harding's unexpected death. Coolidge was given credit for a booming economy at home and no visible crises abroad, and he faced little opposition at the 1924 Republican National Convention. The Democratic Party nominated former Congressman and ambassador to the United Kingdom John W. Davis of West Virginia. Davis, a compromise candidate, triumphed on the 103rd ballot of the 1924 Democratic National Convention after a deadlock between supporters of William Gibbs McAdoo and Al Smith. Dissatisfied by the conservatism of both major party candidates, the newly formed Progressive Party nominated Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin.

In a 2010 book, Garland S. Tucker argues that the election marked the "high tide of American conservatism", as both major candidates campaigned for limited government, reduced taxes, and less regulation.[2] By contrast, La Follette called for the gradual nationalization of the railroads and increased taxes on the wealthy, policies that foreshadowed The New Deal.

Coolidge won a landslide victory, taking majorities in both the popular vote and the Electoral College and winning almost every state outside of the Solid South. La Follette won 16.6% of the popular vote, a strong showing for a third-party candidate, while Davis won the lowest share of the popular vote of any Democratic nominee in history. This was one of only three elections with more than two major candidates where any candidate received a majority of popular votes cast, the others being 1832 and 1980. This is the most recent election to date in which a third-party candidate won a non-southern state. This was also the US election with the lowest per capita voter turnout since records were kept.[3]

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Calvin Coolidge | Charles G. Dawes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30th President of the United States (1923–1929) |

1st Director of the Bureau of the Budget (1921–1922) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Republican candidates

The Republican Convention was held in Cleveland, Ohio, from June 10 to 12, with the easy choice of nominating incumbent President Coolidge for a full term of his own. Former Illinois Governor Frank Orren Lowden was nominated as Coolidge's running mate, but he declined the honor, a unique event in 20th-century American political history. Charles G. Dawes, a prominent Republican businessman, was nominated for vice-president instead.

| 1924 RNC presidential ballot (1) | 1924 RNC vice presidential ballots (1–3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presidential ballot | 1 | Vice presidential ballot | 1 | 2 Before shifts | 2 After shifts | 3 | ||

| Calvin Coolidge | 1065 | Charles G. Dawes | 149 | 111 | 49 | 682.5 | ||

| Robert M. La Follette | 34 | Frank Orren Lowden | 222 | 413 | 766 | 0 | ||

| Hiram Johnson | 10 | Theodore E. Burton | 139 | 288 | 94 | 0 | ||

| Herbert Hoover | 0 | 0 | 0 | 234.5 | ||||

| William S. Kenyon | 172 | 95 | 68 | 75 | ||||

| George Scott Graham | 81 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| James Eli Watson | 79 | 55 | 7 | 45 | ||||

| Charles Curtis | 56 | 31 | 24 | 0 | ||||

| Arthur M. Hyde | 55 | 36 | 36 | 0 | ||||

| George W. Norris | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Smith W. Brookhart | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Frank T. Hines | 28 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Charles A. March | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| J. Will Taylor | 21 | 20 | 27 | 27 | ||||

| William Purnell Jackson | 23 | 0 | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Charles B. Warren | 10 | 1 | 23 | 14 | ||||

| T. Coleman du Pont | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | ||||

| Joseph M. Dixon | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| Everett Sanders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||||

| James Harbord | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Albert J. Beveridge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||

| John L. Coulter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| William Wrigley | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| John J. Pershing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

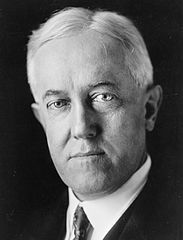

Democratic Party nomination

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John W. Davis | Charles W. Bryan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom (1918–1921) |

20th Governor of Nebraska (1923–1925) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Democratic candidates:

The 1924 Democratic National Convention was held in New York City from June 24 to July 9. The two leading candidates were William Gibbs McAdoo of California, former Secretary of the Treasury and son-in-law of former President Woodrow Wilson, and Governor Al Smith of New York. The balloting revealed a clear geographic and cultural split in the party, as McAdoo was supported mostly by rural, Protestant delegates from the South, West, and small-town Midwest who were supporters of Prohibition (called "drys"). In some cases, McAdoo's delegates were also supporters of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was at its peak of nationwide popularity in the 1920s, with chapters in all 48 states and 4 to 5 million members. Governor Smith was supported by the anti-Prohibition forces (called "wets"), many Roman Catholics and other ethnic minorities, big-city delegates in the Northeast and urban Midwest, and by liberal delegates opposed to the influence of the Ku Klux Klan.

An example of the deep split within the party came in a brutal floor fight over a proposal to publicly condemn the Klan. Most of McAdoo's delegates in the South and West opposed the motion, while most of Smith's big-city delegates supported it. In the end the motion failed to carry by a single vote. William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic presidential candidate, argued against condemning the Klan for fear that it would permanently split the party. Wendell Willkie, who would go on to become the Republican Party's 1940 presidential candidate, was a Democratic delegate in 1924, and he supported the proposal to condemn the KKK. The bitter fight between the McAdoo and Smith delegates over the KKK set the stage for the nominating ballots to come. Most of the ensuing ballots followed a pattern of having McAdoo leading, Smith second, Davis third, and 1920 candidate James M. Cox fourth, followed by various favorite son candidates.

Due to the two-thirds rule governing nominations, neither McAdoo, who briefly got a majority of the votes halfway through the balloting, nor Smith was able to get the two-thirds majority necessary to win. However, neither candidate would back down, and so the deadlock continued for days on end, as ballot after ballot was taken with neither McAdoo or Smith getting close to enough delegates to win the nomination. Cox withdrew after the 64th ballot, only for his support to split relatively evenly between the three frontrunners, leaving the situation no closer to being resolved. Eventually the convention would go to over 100 ballots, becoming the longest-running political convention in American history. Humorist Will Rogers joked that New York had invited the Democratic delegates to visit the city, not to live there. As the convention approached the hundredth ballot, a movement to draft Indiana senator Samuel M. Ralston gained traction and began to look like it might break the deadlock; Ralston, who had been content for his name to be put forward purely as a favorite son candidate, quickly sent the convention a message stating that due to his poor health, he could not accept the nomination.

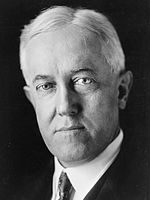

Due to the great divide in the Democratic Party, the convention could have gone on for a great deal longer. However, with some state delegations running low on money and unable to stay in the city any longer, on the 100th ballot both Smith and McAdoo mutually withdrew as candidates. This allowed the convention's delegates to search for a compromise candidate acceptable to both Smith and McAdoo supporters.[4] Finally, on the 103rd ballot, the exhausted convention turned to John W. Davis, a former Congressman from West Virginia, former Solicitor General of the United States, and former United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom, as the presidential nominee. The Democrats' disarray prompted Will Rogers's famous quip: "I'm not a member of any organized political party, I'm a Democrat!"

Governor of Nebraska Charles W. Bryan, William Jennings Bryan's brother, was nominated for vice-president in order to gain the support of the party's rural voters, many of whom still saw Bryan as their leader.

| (1-20) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 31 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 34.5 | 55.5 | 55 | 57 | 63 | 57.5 | 59 | 60 | 64.5 | 64.5 | 61 | 63 | 64 | 66 | 84.5 | 122 | |||||

| McAdoo | 431.5 | 431 | 437 | 443.6 | 443.1 | 443.1 | 442.6 | 444.6 | 444.6 | 471.6 | 476.3 | 478.5 | 477 | 475.5 | 479 | 478 | 471.5 | 470.5 | 474 | 432 | |||||

| Smith | 241 | 251.5 | 255.5 | 260 | 261 | 261.5 | 261.5 | 273.5 | 278 | 299.5 | 303.2 | 301 | 303.5 | 306.5 | 305.5 | 305.5 | 312.5 | 312.5 | 311.5 | 307.5 | |||||

| Cox | 59 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||||

| Harrison | 43.5 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 31.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Underwood | 42.5 | 42 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 42.5 | 42.5 | 48 | 45.5 | 43.9 | 42.5 | 41.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 39.5 | 41.5 | 42 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 45.5 | |||||

| Silzer | 38 | 30 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ferris | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 32.5 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 30 | |||||

| Glass | 25 | 25 | 29 | 45 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25.5 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 44 | 30 | 30 | 25 | |||||

| Ritchie | 22.5 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 42.9 | 22.9 | 20.9 | 19.9 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Robinson | 21 | 41 | 41 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 46 | 28 | 22 | 22 | 21 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 20 | 23 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 29 | 32.4 | 12 | 11 | 13.5 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | |||||

| Brown | 17 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 9.9 | 8.5 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Sweet | 12 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Kendrick | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Thompson | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| W.J. Bryan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Krebs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Copeland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Hull | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Hitchcock | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Dever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |||||

| (21–40) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | 25th | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 125 | 123.5 | 129.5 | 129.5 | 126 | 125 | 128.5 | 126 | 124.5 | 126.5 | 127.5 | 128 | 121 | 107.5 | 107 | 106.5 | 107 | 105 | 71 | 70 | |||||

| McAdoo | 439 | 438.5 | 438.5 | 438.5 | 436.5 | 415.5 | 413 | 412 | 415 | 415.5 | 415.5 | 415.5 | 404.5 | 445 | 439 | 429 | 444.5 | 444 | 499 | 506.4 | |||||

| Smith | 307.5 | 307.5 | 308 | 308 | 308.5 | 311.5 | 316.5 | 316.5 | 321 | 323.5 | 322.5 | 322 | 310.5 | 311 | 323.5 | 323 | 321 | 321 | 320.5 | 315.1 | |||||

| Cox | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 54 | 50 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | |||||

| Underwood | 45.5 | 45.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 41.5 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 32 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 33 | 33.5 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | |||||

| Glass | 24 | 25 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 24 | |||||

| Robinson | 22 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | |||||

| Ritchie | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Walsh | 8 | 8.5 | 8 | 9 | 16 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Baker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Miller | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Pomerene | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Owen | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 5 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| Daniels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Martin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Gaston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Doheny | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Jackson | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| (41–60) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th | 46th | 47th | 48th | 49th | 50th | 51st | 52nd | 53rd | 54th | 55th | 56th | 57th | 58th | 59th | 60th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 70 | 67 | 71 | 71 | 73 | 71 | 70.5 | 70.5 | 63.5 | 64 | 67.5 | 59 | 63 | 62 | 62.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 40.5 | 60 | 60 | |||||

| McAdoo | 504.9 | 503.4 | 483.4 | 484.4 | 483.4 | 486.9 | 484.4 | 483.5 | 462.5 | 461.5 | 442.5 | 413.5 | 423.5 | 427 | 426.5 | 430 | 430 | 495 | 473.5 | 469.5 | |||||

| Smith | 317.6 | 318.6 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 319.1 | 320.1 | 321 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 328 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 320.5 | 331.5 | 331.5 | 330.5 | |||||

| Cox | 55 | 56 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 54 | |||||

| Underwood | 39.5 | 39.5 | 40 | 39 | 38 | 37.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 42 | 42.5 | 43 | 38.5 | 42.5 | 40 | 40 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 38 | 40 | 42 | |||||

| Ralston | 30 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 57 | 58 | 63 | 93 | 94 | 92 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 40.5 | 42.5 | 42.5 | |||||

| Glass | 24 | 28.5 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |||||

| Robinson | 24 | 23 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 45 | 44 | 43 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 23 | 23 | 23 | |||||

| Ritchie | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Owen | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 24 | 24 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Spellacy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| Edwards | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Battle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Behrman | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| (61–80) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61st | 62nd | 63rd | 64th | 65th | 66th | 67th | 68th | 69th | 70th | 71st | 72nd | 73rd | 74th | 75th | 76th | 77th | 78th | 79th | 80th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 60 | 60.5 | 62 | 61.5 | 71.5 | 74.5 | 75.5 | 72.5 | 64 | 67 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 78.5 | 78.5 | 75.5 | 76.5 | 73.5 | 71 | 73.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 469.5 | 469 | 446.5 | 488.5 | 492 | 495 | 490 | 488.5 | 530 | 528.5 | 528.5 | 527.5 | 528 | 510 | 513 | 513 | 513 | 511 | 507.5 | 454.5 | |||||

| Smith | 335.5 | 338.5 | 315.5 | 325 | 336.5 | 338.5 | 336.5 | 336.5 | 335 | 334 | 334.5 | 334 | 335 | 364 | 366 | 368 | 367 | 363.5 | 366.5 | 367.5 | |||||

| Cox | 54 | 49 | 49 | 54 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Underwood | 42 | 40 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 40 | 39.5 | 46.5 | 46.5 | 38 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 38.5 | 47 | 46.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 49 | 50 | 46.5 | |||||

| Ralston | 37.5 | 38.5 | 56 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| Glass | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 21 | 17 | 68 | |||||

| Owen | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Robinson | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 22.5 | 28.5 | 29.5 | |||||

| Ritchie | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| Ferris | 0 | 0 | 28 | 24.5 | 6.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 18 | 17.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 55 | 54 | 57 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 57.5 | 54 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Wheeler | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Rogers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Coolidge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Daniels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Kevin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| (81–100) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81st | 82nd | 83rd | 84th | 85th | 86th | 87th | 88th | 89th | 90th | 91st | 92nd | 93rd | 94th | 95th | 96th | 97th | 98th | 99th | 100th | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 70.5 | 71 | 72.5 | 66 | 68 | 65.5 | 66.5 | 59.5 | 64.5 | 65.5 | 66.5 | 69.5 | 68 | 81.75 | 139.25 | 171.5 | 183.25 | 194.75 | 210 | 203.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 432 | 413.5 | 418 | 388.5 | 380.5 | 353.5 | 336.5 | 315.5 | 318.5 | 314 | 318 | 310 | 314 | 395 | 417.5 | 421 | 415.5 | 406.5 | 353.5 | 190 | |||||

| Smith | 365 | 366 | 368 | 365 | 363 | 360 | 361.5 | 362 | 357 | 354.5 | 355.5 | 355.5 | 355.5 | 364.5 | 367.5 | 359.5 | 359.5 | 354 | 354 | 351.5 | |||||

| Glass | 73 | 78 | 76 | 72.5 | 67.5 | 72.5 | 71 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 30.5 | 28.5 | 26.5 | 27 | 37 | 34 | 39 | 39 | 36 | 38 | 35 | |||||

| Underwood | 48 | 49 | 48.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 41 | 42.5 | 46.5 | 45.25 | 44.75 | 46.25 | 44.25 | 38.5 | 37.25 | 38.25 | 39.5 | 41.5 | |||||

| Robinson | 29.5 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 25 | 27.5 | 25 | 20.5 | 23 | 20.5 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 37 | 31 | 32 | 22 | 25 | 25 | 46 | |||||

| Owen | 21 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 20 | |||||

| Ritchie | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 23.5 | 23 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 20.5 | 21.5 | 19.5 | 18.5 | 17.5 | 17.5 | |||||

| Ferris | 16 | 12 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Walsh | 7 | 4 | 4 | 1.5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3.5 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 52.5 | |||||

| Saulsbury | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Ralston | 4 | 24 | 24 | 86 | 87 | 92 | 93 | 98 | 100.5 | 159.5 | 187.5 | 196.75 | 196.25 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Barnett | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Daniels | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 19.5 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | |||||

| Roosevelt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Miller | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Wheeler | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Coyne | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| Meredith | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 75.5 | |||||

| Maloney | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| J.M. Davis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cox | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Houston | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |||||

| Callahan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Copeland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Stewart | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Marshall | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Gerard | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |||||

| (101–103) | Presidential Ballot | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101st | 102nd | 103rd before shifts |

103rd after shifts | ||||||

| J.W. Davis | 316 | 415.5 | 575.5 | 844 | |||||

| Underwood | 229.5 | 317 | 250.5 | 102.5 | |||||

| Walsh | 98 | 123 | 84.5 | 58 | |||||

| Glass | 59 | 67 | 79 | 23 | |||||

| Robinson | 22.5 | 21 | 21 | 20 | |||||

| Meredith | 130 | 66.5 | 42.5 | 15.5 | |||||

| McAdoo | 52 | 21 | 14.5 | 11.5 | |||||

| Smith | 121 | 44 | 10.5 | 7.5 | |||||

| Gerard | 16 | 7 | 8 | 7 | |||||

| Hull | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Daniels | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Thompson | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Berry | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Allen | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| C.W. Bryan | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ritchie | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Owen | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Cummings | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Houston | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Murphree | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Baker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Vice Presidential Ballot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First ballot | before shifts | after shifts | ||

| Governor C. W. Bryan | 332 | 739 | ||

| George Berry | 270.5 | 212 | ||

| Bennett Clark | – | 42 | ||

| Lena Springs | 42 | 18 | ||

| Colonel Alvin Owsley | – | 16 | ||

| Governor George S. Silzer | – | 10 | ||

| Mayor John F. Hylan | 109 | 6 | ||

| Governor Jonathan M. Davis | – | 4 | ||

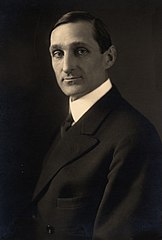

Progressive Party nomination

| 1924 Progressive Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Robert M. La Follette | Burton K. Wheeler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Senator from Wisconsin (1906–1925) |

U.S. Senator from Montana (1923–1947) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Senator Robert M. La Follette, who had left the Republican Party and formed his own political party, the Progressive Party, in Wisconsin, was so upset over both political parties choosing conservative candidates that he decided to run as a third-party candidate to give liberals from both parties an alternative. He thus accepted the presidential nomination of the Progressive Party. A longtime champion of labor unions, and an ardent foe of Big Business, La Follette was a fiery orator who had dominated Wisconsin's political scene for more than two decades. Backed by radical farmers, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) labor unions, and Socialists, La Follette ran on a platform of nationalizing cigarette factories and other large industries. He also strongly supported increased taxation on the wealthy and the right of collective bargaining for factory workers. Despite a strong showing in labor strongholds and winning over 16% of the national popular vote, he carried only his home state of Wisconsin in the electoral college.

Results

This was the first presidential election in which all American Indians were recognized as citizens and allowed to vote. The total vote increased by 2,300,000 but, because of the great drawing power of the La Follette candidacy, both the Republican and Democratic totals were less. Largely because of the deep inroads made by La Follette in the Democratic vote, Davis polled 750,000 fewer votes than were cast for Cox in 1920. Coolidge polled 425,000 votes less than Harding had in 1920. Nonetheless, La Follette's appeal among liberal Democrats allowed Coolidge to achieve a 25.2 percent margin of victory over Davis in the popular vote (the second largest since 1824, and the largest in the last century). Davis's popular vote percentage of 28.8% remains the lowest of any Democratic presidential candidate (not counting John C. Breckinridge's run on a Southern Democratic ticket in 1860, when the vote was split with Stephen A. Douglas, the main Democratic candidate), albeit with several other candidates performing worse in the electoral college.

Both La Follette and Davis had criticized the Ku Klux Klan during the campaign, but Coolidge did not speak on the issue despite pleas from black groups. The New York Times stated that "Either Mr. Coolidge holds his peace for mistaken reasons of policy and politics or he tolerates the Klan". Charles G. Dawes criticized the KKK on August 23, but his comments were criticized by Representative Fiorello La Guardia who stated that "General Dawes praised the Klan with faint damn".[6][7]

The "other" vote amounted to nearly five million, owing in largest part to the 4,832,614 votes cast for La Follette. This candidacy, like that of Roosevelt in 1912, altered the distribution of the vote throughout the country and particularly in eighteen states in the Middle and Far West. Unlike the Roosevelt vote of 1912, the La Follette vote included most of the Socialist strength.

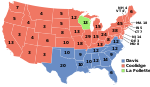

The La Follette vote was distributed over the nation, and in every state, but its greatest strength lay in the East North Central and West North Central sections. However, La Follette carried no section, and he was second in only two sections, the Mountain and Pacific areas. In twelve states, the La Follette vote was greater than that cast for Davis. In one of these states, Wisconsin, La Follette defeated the Republican ticket also, thus winning one state in the electoral college. The "other" vote led the poll in 235 counties, and practically all of these (225) gave La Follette a plurality. Four counties, three in the South, recorded zero votes, as against seven in 1920 – this decrease reflecting the Indian Citizenship Act.

With most of the third-party vote united under La Follette's candidacy, the Prohibition Party dropped to less than a third of the popular vote percentage that it had earned four years prior. This was the end of the Prohibitionists as a significant political force; having regularly earned at least a percentage point of the popular vote since 1884, they would struggle to earn even a tenth of that number in the decades ahead as Prohibition became increasingly unpopular and was eventually repealed in 1933, though the party nominally continues to exist and contest presidential elections to this day.

Davis won in 1,279 counties, which was 183 more than what Cox had received, and Coolidge failed to win in 377 counties that Harding had won in 1920. Coolidge's net vote totals in the twelve largest cities were less than Harding's with Coolidge only receiving 1,308,000 compared to Harding's 1,540,000.[6] The inroads of the La Follette candidacy upon the Democratic Party were in areas where Democratic county majorities had been infrequent in the Fourth Party System. At the same time, the inroads of La Follette's candidacy upon the Republican Party were in areas where in this national contest their candidate could afford to be second or third in the poll.[8] Thus, Davis carried only the traditionally Democratic Solid South and Oklahoma; due to liberal Democrats voting for La Follette, Davis lost the popular vote to Coolidge by 25.2 percentage points. Only Warren Harding, who finished 26.2 points ahead of his nearest competitor in the previous election, did better in this category in competition between multiple candidates (incumbent James Monroe was the only candidate in 1820 and thus took every vote).

The combined vote for Davis and La Follette over the nation was exceeded by Coolidge by 2,500,000. Nevertheless, in thirteen states (four border and nine western), Coolidge received only a plurality. The Coolidge vote topped the poll, however, in thirty-five states, leaving the electoral vote for Davis in only twelve.[9] All the states of the former Confederacy voted for Davis (plus Oklahoma), while all of the Union/postbellum states (except Wisconsin and Oklahoma) voted for Coolidge. It remains the last time anyone won the presidency without carrying a single former Confederate state.

This was the last election in which Republicans won Massachusetts and Rhode Island until 1952. The Republicans did so well that they carried New York City, a feat they have not repeated since, and this was also the last election in which they carried Suffolk County, Massachusetts; Ramsey County, Minnesota; Costilla County, Colorado; Deer Lodge County, Montana;[10] or the City of St. Louis, Missouri. Davis did not carry any counties in twenty of the forty-eight states, two fewer than Cox during the previous election, but nonetheless, an ignominy approached since only by George McGovern in his landslide 1972 loss. Davis did not carry one county in any state bordering Canada or the Pacific. The election was the last time a Republican won the presidency without Florida, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. It was the first time ever that a Republican won without Wisconsin. This election (along with 1920) are the only two elections since the Civil War where national turnout was below 50%.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Calvin Coolidge (incumbent) | Republican | Massachusetts | 15,723,789 | 54.04% | 382 | Charles G. Dawes | Illinois | 382 |

| John W. Davis | Democratic | West Virginia | 8,386,242 | 28.82% | 136 | Charles W. Bryan | Nebraska | 136 |

| Robert M. La Follette | Progressive-Socialist-Farmer–Labor | Wisconsin | 4,831,706 | 16.61% | 13 | Burton K. Wheeler | Montana | 13 |

| Herman P. Faris | Prohibition | Missouri | 55,951 | 0.19% | 0 | Marie C. Brehm | California | 0 |

| William Z. Foster | Communist | Massachusetts | 38,669 | 0.13% | 0 | Benjamin Gitlow | New York | 0 |

| Frank T. Johns | Socialist Labor | Oregon | 28,633 | 0.10% | 0 | Verne L. Reynolds | New York | 0 |

| Gilbert Nations | American | District of Columbia | 24,325 | 0.08% | 0 | Charles Hiram Randall | California | 0 |

| Other | 7,792 | 0.03% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 29,097,107 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1924 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

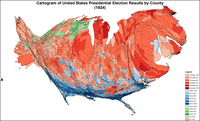

Geography of results

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

-

Map of presidential election results by county

-

Map of Republican presidential election results by county

-

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

-

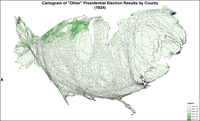

Map of "other" presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source:[11]

| States/districts won by Davis/Bryan |

| States/districts won by La Follette/Wheeler |

| States/districts won by Coolidge/Dawes |

| Calvin Coolidge Republican |

John W. Davis Democratic |

Robert La Follette Progressive |

Herman Faris Prohibition |

William Foster Communist |

Frank Johns Socialist Labor |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 12 | 45,005 | 27.01 | - | 112,966 | 67.81 | 12 | 8,084 | 4.85 | - | 538 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -67,961 | -40.79 | 166,593 | AL |

| Arizona | 3 | 30,516 | 41.26 | 3 | 26,235 | 35.47 | - | 17,210 | 23.27 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4,281 | 5.79 | 73,961 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 9 | 40,564 | 29.28 | - | 84,795 | 61.21 | 9 | 13,173 | 9.51 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -44,231 | -31.93 | 138,532 | AR |

| California | 13 | 733,250 | 57.20 | 13 | 105,514 | 8.23 | - | 424,649 | 33.13 | - | 18,365 | 1.43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 308,601 | 24.07 | 1,281,900 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 195,171 | 57.02 | 6 | 75,238 | 21.98 | - | 69,945 | 20.44 | - | 966 | 0.28 | - | 562 | 0.16 | - | 378 | 0.11 | - | 119,933 | 35.04 | 342,260 | CO |

| Connecticut | 7 | 246,322 | 61.54 | 7 | 110,184 | 27.53 | - | 42,416 | 10.60 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1,373 | 0.34 | - | 136,138 | 34.01 | 400,295 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 52,441 | 57.70 | 3 | 33,445 | 36.80 | - | 4,979 | 5.48 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18,996 | 20.90 | 90,885 | DE |

| Florida | 6 | 30,633 | 28.06 | - | 62,083 | 56.88 | 6 | 8,625 | 7.90 | - | 5,498 | 5.04 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -31,450 | -28.81 | 109,154 | FL |

| Georgia | 14 | 30,300 | 18.19 | - | 123,200 | 73.96 | 14 | 12,691 | 7.62 | - | 231 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -92,900 | -55.77 | 166,577 | GA |

| Idaho | 4 | 69,879 | 47.12 | 4 | 24,256 | 16.36 | - | 54,160 | 36.52 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15,719 | 10.60 | 148,295 | ID |

| Illinois | 29 | 1,453,321 | 58.84 | 29 | 576,975 | 23.36 | - | 432,027 | 17.49 | - | 2,367 | 0.10 | - | 2,622 | 0.11 | - | 2,334 | 0.09 | - | 876,346 | 35.48 | 2,470,067 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 703,042 | 55.25 | 15 | 492,245 | 38.69 | - | 71,700 | 5.64 | - | 4,416 | 0.35 | - | 987 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | 210,797 | 16.57 | 1,272,390 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 537,635 | 55.03 | 13 | 162,600 | 16.64 | - | 272,243 | 27.87 | - | - | - | - | 4,037 | 0.41 | - | - | - | - | 265,392 | 27.17 | 976,960 | IA |

| Kansas | 10 | 407,671 | 61.54 | 10 | 156,319 | 23.60 | - | 98,461 | 14.86 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 251,352 | 37.94 | 662,454 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 398,966 | 48.93 | 13 | 374,855 | 45.98 | - | 38,465 | 4.72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1,499 | 0.18 | - | 24,111 | 2.96 | 815,332 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 24,670 | 20.23 | - | 93,218 | 76.44 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -68,548 | -56.21 | 121,951 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 138,440 | 72.03 | 6 | 41,964 | 21.83 | - | 11,382 | 5.92 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 406 | 0.21 | - | 96,476 | 50.20 | 192,192 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 162,414 | 45.29 | 8 | 148,072 | 41.29 | - | 47,157 | 13.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 987 | 0.28 | - | 14,342 | 4.00 | 358,630 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 18 | 703,476 | 62.26 | 18 | 280,831 | 24.86 | - | 141,225 | 12.50 | - | - | - | - | 2,635 | 0.23 | - | 1,668 | 0.15 | - | 422,645 | 37.41 | 1,129,837 | MA |

| Michigan | 15 | 874,631 | 75.37 | 15 | 152,359 | 13.13 | - | 122,014 | 10.51 | - | 6,085 | 0.52 | - | 5,330 | 0.46 | - | - | - | - | 722,272 | 62.24 | 1,160,419 | MI |

| Minnesota | 12 | 420,759 | 51.18 | 12 | 55,913 | 6.80 | - | 339,192 | 41.26 | - | - | - | - | 4,427 | 0.54 | - | 1,855 | 0.23 | - | 81,567 | 9.92 | 822,146 | MN |

| Mississippi | 10 | 8,494 | 7.55 | - | 100,474 | 89.34 | 10 | 3,494 | 3.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -91,980 | -81.79 | 112,462 | MS |

| Missouri | 18 | 648,486 | 49.58 | 18 | 572,753 | 43.79 | - | 84,160 | 6.43 | - | 1,418 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | 883 | 0.07 | - | 75,733 | 5.79 | 1,307,958 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 74,138 | 42.50 | 4 | 33,805 | 19.38 | - | 66,123 | 37.91 | - | - | - | - | 357 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | 8,015 | 4.60 | 174,423 | MT |

| Nebraska | 8 | 218,585 | 47.09 | 8 | 137,289 | 29.58 | - | 106,701 | 22.99 | - | 1,594 | 0.34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 81,296 | 17.51 | 464,173 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 11,243 | 41.76 | 3 | 5,909 | 21.95 | - | 9,769 | 36.29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1,474 | 5.48 | 26,921 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 98,575 | 59.83 | 4 | 57,201 | 34.72 | - | 8,993 | 5.46 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 41,374 | 25.11 | 164,769 | NH |

| New Jersey | 14 | 675,162 | 62.17 | 14 | 297,743 | 27.41 | - | 108,901 | 10.03 | - | 1,337 | 0.12 | - | 1,540 | 0.14 | - | 819 | 0.08 | - | 377,419 | 34.75 | 1,086,079 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 3 | 54,745 | 48.52 | 3 | 48,542 | 43.02 | - | 9,543 | 8.46 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6,203 | 5.50 | 112,830 | NM |

| New York | 45 | 1,820,058 | 55.76 | 45 | 950,796 | 29.13 | - | 474,913 | 14.55 | - | - | - | - | 8,244 | 0.25 | - | 9,928 | 0.30 | - | 869,262 | 26.63 | 3,263,939 | NY |

| North Carolina | 12 | 191,753 | 39.73 | - | 284,270 | 58.89 | 12 | 6,651 | 1.38 | - | 13 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -92,517 | -19.17 | 482,687 | NC |

| North Dakota | 5 | 94,931 | 47.68 | 5 | 13,858 | 6.96 | - | 89,922 | 45.17 | - | - | - | - | 370 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | 5,009 | 2.52 | 199,081 | ND |

| Ohio | 24 | 1,176,130 | 58.33 | 24 | 477,888 | 23.70 | - | 357,948 | 17.75 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3,025 | 0.15 | - | 698,242 | 34.63 | 2,016,237 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 10 | 226,242 | 42.82 | - | 255,798 | 48.41 | 10 | 46,375 | 8.78 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -29,556 | -5.59 | 528,415 | OK |

| Oregon | 5 | 142,579 | 51.01 | 5 | 67,589 | 24.18 | - | 68,403 | 24.47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 917 | 0.33 | - | 74,176 | 26.54 | 279,488 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 38 | 1,401,481 | 65.34 | 38 | 409,192 | 19.08 | - | 307,567 | 14.34 | - | 9,779 | 0.46 | - | 2,735 | 0.13 | - | 634 | 0.03 | - | 992,289 | 46.26 | 2,144,850 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 5 | 125,286 | 59.63 | 5 | 76,606 | 36.46 | - | 7,628 | 3.63 | - | - | - | - | 289 | 0.14 | - | 268 | 0.13 | - | 48,680 | 23.17 | 210,115 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 1,123 | 2.21 | - | 49,008 | 96.56 | 9 | 620 | 1.22 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -47,885 | -94.35 | 50,752 | SC |

| South Dakota | 5 | 101,299 | 49.69 | 5 | 27,214 | 13.35 | - | 75,355 | 36.96 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 25,944 | 12.73 | 203,868 | SD |

| Tennessee | 12 | 130,882 | 43.59 | - | 158,537 | 52.80 | 12 | 10,656 | 3.55 | - | 100 | 0.03 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -27,655 | -9.21 | 300,275 | TN |

| Texas | 20 | 130,023 | 19.78 | - | 484,605 | 73.70 | 20 | 42,881 | 6.52 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -354,582 | -53.93 | 657,509 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 77,327 | 49.26 | 4 | 47,001 | 29.94 | - | 32,662 | 20.81 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30,326 | 19.32 | 156,990 | UT |

| Vermont | 4 | 80,498 | 78.22 | 4 | 16,124 | 15.67 | - | 5,964 | 5.79 | - | 326 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 64,374 | 62.55 | 102,917 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 73,312 | 32.79 | - | 139,716 | 62.48 | 12 | 10,377 | 4.64 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 197 | 0.09 | - | -66,404 | -29.70 | 223,602 | VA |

| Washington | 7 | 220,224 | 52.24 | 7 | 42,842 | 10.16 | - | 150,727 | 35.76 | - | - | - | - | 761 | 0.18 | - | 1,004 | 0.24 | - | 69,497 | 16.49 | 421,549 | WA |

| West Virginia | 8 | 288,635 | 49.45 | 8 | 257,232 | 44.07 | - | 36,723 | 6.29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 31,403 | 5.38 | 583,662 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 13 | 311,614 | 37.06 | - | 68,115 | 8.10 | - | 453,678 | 53.96 | 13 | 2,918 | 0.35 | - | 3,773 | 0.45 | - | 458 | 0.05 | - | -142,064 | -16.90 | 840,826 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 41,858 | 52.39 | 3 | 12,868 | 16.11 | - | 25,174 | 31.51 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16,684 | 20.88 | 79,900 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 531 | 15,723,789 | 54.04 | 382 | 8,386,242 | 28.82 | 136 | 4,831,706 | 16.61 | 13 | 55,951 | 0.19 | - | 38,669 | 0.13 | - | 28,633 | 0.10 | - | 7,337,547 | 25.22 | 29,097,107 | US |

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

States that flipped from Democratic to Republican

States that flipped from Republican to Progressive

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (30 electoral votes):

- North Dakota, 2.52% (5,009 votes)

- Kentucky, 2.96% (24,111 votes)

- Maryland, 4.00% (14,342 votes)

- Montana, 4.60% (8,015 votes)

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (69 electoral votes):

- West Virginia, 5.38% (31,403 votes)

- Nevada, 5.48% (1,474 votes)

- New Mexico, 5.50% (6,203 votes)

- Oklahoma, 5.59% (29,556 votes)

- Arizona, 5.79% (4,281 votes)

- Missouri, 5.79% (75,733 votes)

- Tennessee, 9.21% (27,655 votes)

- Minnesota, 9.92% (81,567 votes)

Tipping point state:

- Nebraska, 17.51% (81,296 votes) (tipping point state for a Coolidge victory)

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Johnson County, Tennessee 91.32%

- Keweenaw County, Michigan 91.15%

- Shannon County, South Dakota 88.89%

- Leslie County, Kentucky 88.83%

- Windsor County, Vermont 88.43%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Edgefield County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Marlboro County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Kershaw County, South Carolina 99.86%

- Horry County, South Carolina 99.70%

- Marion County, South Carolina 99.68%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Progressive)

- Comal County, Texas 73.96%

- Mercer County, North Dakota 71.38%

- Shawano County, Wisconsin 70.69%

- Hutchinson County, South Dakota 70.38%

- Calumet County, Wisconsin 69.42%

Notes

- ^ Frank O. Lowden had originally been nominated as Coolidge's running mate, however Lowden declined the nomination and Dawes was chosen instead.

See also

- History of the United States (1918–1945)

- Progressive Era

- 1924 United States Senate elections

- 1924 United States House of Representatives elections

- Second inauguration of Calvin Coolidge

References

- ^ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- ^ Garland S. Tucker III, The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge and the 1924 Election (Emerald, 2010)

- ^ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections | The American Presidency Project". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Prude, James (1972). "William Gibbs McAdoo and the Democratic National Convention of 1924". The Journal of Southern History. 38 (4). Southern Historical Association: 621–628. doi:10.2307/2206152. JSTOR 2206152.

- ^ The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932 – Google Books. Stanford University Press. 1934. ISBN 9780804716963. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ a b Murphy, Paul (1974). Political Parties In American History, Volume 3, 1890-present. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ^ "General 'Opposed to' Klan; But Dawes Says But Many Join It in Interest of Law and Order". The New York Times. August 24, 1924. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022.

- ^ The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 24

- ^ The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 23

- ^ Sullivan, Robert David; ‘How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century’; America Magazine in The National Catholic Review; June 29, 2016

- ^ "1924 Presidential General Election Data - National". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

Further reading

- Burner, David. The Politics of Provincialism: The Democratic Party in Transition, 1918-1932 (1968)

- Chalmers, David. "The Ku Klux Klan in politics in the 1920's." Mississippi Quarterly 18.4 (1965): 234-247 online.

- Craig, Douglas B. After Wilson: The Struggle for the Democratic Party, 1920-1934 (1993)

- Davies, Gareth, and Julian E. Zelizer, eds. America at the Ballot Box: Elections and Political History (2015) pp. 139–52.

- Hicks, John Donald (1955). Republican Ascendancy 1921-1933. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-011885-7.

- Goldberg, David J. "Unmasking the Ku Klux Klan: The northern movement against the KKK, 1920-1925." Journal of American Ethnic History (1996): 32-48 online.

- MacKay, K. C. (1947). The Progressive Movement of 1924. New York: Octagon Books. ISBN 0-374-95244-2.

- McVeigh, Rory. "Power Devaluation, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Democratic National Convention of 1924." Sociological Forum 16#1 (2001) abstract.

- McCoy, Donald R. (1967). Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-7006-0350-6.

- Martinson, David L. "Coverage of La Follette Offers Insights for 1972 Campaign." Journalism Quarterly 52.3 (1975): 539–542.

- Murray, Robert K. (1976). The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and Disaster in Madison Square Garden. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-013124-1.

- Prude, James C. "William Gibbs McAdoo and the Democratic National Convention of 1924." Journal of Southern History 38.4 (1972): 621-628 online.

- Ranson, Edward. The Role of Radio in the American Presidential Election of 1924: How a New Communications Technology Shapes the Political Process (Edwin Mellen Press; 2010) 165 pages. Looks at Coolidge as a radio personality, and how radio figured in the campaign, the national conventions, and the election result.

- Tucker, Garland S., III. The high tide of American conservatism: Davis, Coolidge, and the 1924 election (2010) online

- Unger, Nancy C. (2000). Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2545-X.

Primary sources

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

- 1924 popular vote by counties

- Election of 1924 in Counting the Votes Archived March 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine