The 2000 United States presidential election was the 54th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 2000. Republican Texas Governor George W. Bush, the eldest son of George H. W. Bush, narrowly defeated incumbent Democratic Vice President Al Gore. It was the fourth of five U.S. presidential elections, and the first since 1888, in which the winning candidate lost the popular vote, and is considered one of the closest U.S. presidential elections, with long-standing controversy about the result.[2][3][4][5] Gore conceded the election on December 13.

Incumbent Democratic President Bill Clinton was ineligible to seek a third term because of term limits established by the 22nd Amendment. Incumbent Vice President Gore easily secured the Democratic nomination, defeating former New Jersey Senator Bill Bradley in the primaries. He selected Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman as his running mate. Bush was seen as the early favorite for the Republican nomination, and after a contentious primary battle with Arizona Senator John McCain and others, he secured the nomination by Super Tuesday. He selected former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as his running mate.

Both major-party candidates focused primarily on domestic issues, such as the budget, tax relief, and reforms for federal social insurance programs, although foreign policy was not ignored. Due to President Bill Clinton's sex scandal with Monica Lewinsky and subsequent impeachment, Gore avoided campaigning with Clinton. Republicans denounced Clinton's indiscretions, while Gore criticized Bush's lack of experience. On election night, it was unclear who had won, with the electoral votes of the state of Florida still undecided. The returns showed that Bush won Florida by such a close margin that state law required a recount. A month-long series of legal battles led to the highly controversial 5–4 Supreme Court decision Bush v. Gore, which ended the recount.

Bush won Florida by 537 votes, a margin of 0.009%. The Florida recount and subsequent litigation resulted in major post-election controversy, and with speculative analysis suggesting that limited county-based recounts would likely have confirmed a Bush victory, whereas a statewide recount would likely have given the state to Gore.[6][7] Ultimately, Bush won 271 electoral votes, one vote more than the 270-to-win majority, despite Gore receiving 543,895 more votes (a margin of 0.52% of all votes cast).[8] Bush flipped 11 states that had voted Democratic in 1996: Arkansas, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Background

Article Two of the United States Constitution dictates that the President and Vice President of the United States must be natural-born citizens of the United States, at least 35 years old, and residents of the United States for a period of at least 14 years. Candidates for the presidency typically seek the nomination of one of the political parties, in which case each party devises a method (such as a primary election) to choose the candidate the party deems best suited to run for the position. Traditionally, the primary elections are indirect elections where voters cast ballots for a slate of party delegates pledged to a particular candidate. The party's delegates then officially nominate a candidate to run on the party's behalf. The general election in November is also an indirect election, where voters cast ballots for a slate of members of the Electoral College; these electors in turn directly elect the president and vice president.

President Bill Clinton, a Democrat and former Governor of Arkansas, was ineligible to seek reelection to a third term due to the Twenty-second Amendment; in accordance with Section 1 of the Twentieth Amendment, his term expired at noon Eastern Standard Time on January 20, 2001.

Republican Party nomination

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

46th Governor of Texas

43rd President of the United States

Policies

Appointments

First term

Second term

Presidential campaigns Post-presidency

|

||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George W. Bush | Dick Cheney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46th Governor of Texas (1995–2000) |

17th U.S. Secretary of Defense (1989–1993) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Withdrawn candidates

| Candidates in this section are sorted by popular vote from the primaries | ||||||

| John McCain | Alan Keyes | Steve Forbes | Gary Bauer | Orrin Hatch | Elizabeth Dole | Pat Buchanan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U.S. Senator from Arizona (1987–2018) |

Asst. Secretary of State (1985–1987) |

Businessman | U.S. Under Secretary of Education (1985–1987) |

U.S. Senator from Utah (1977–2019) |

U.S. Secretary of Labor (1989–1990) |

White House Communications Director (1985–1987) |

|

|

|

|||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | Campaign |

| W: March 9 6,457,696 votes |

W: July 25 1,009,232 votes |

W: Feb 10 151,362 votes |

W: Feb 4 65,128 votes |

W: Jan 26 20,408 votes |

W: Oct 20 231 votes |

W: Oct 25 0 votes |

Primaries

Bush became the early front-runner, acquiring unprecedented funding and a broad base of leadership support based on his governorship of Texas, the Bush family's name recognition, and connections in American politics. Former cabinet member George Shultz played an important early role in securing establishment Republican support for Bush. In April 1998, he invited Bush to discuss policy issues with experts including Michael Boskin, John Taylor, and Condoleezza Rice, who later became his Secretary of State. The group, which was "looking for a candidate for 2000 with good political instincts, someone they could work with", was impressed, and Shultz encouraged him to enter the race.[9]

Several aspirants withdrew before the Iowa caucuses because they did not secure funding and endorsements sufficient to remain competitive with Bush. These included Elizabeth Dole, Dan Quayle, Lamar Alexander, and Bob Smith. Pat Buchanan dropped out to run for the Reform Party nomination. That left Bush, John McCain, Alan Keyes, Steve Forbes, Gary Bauer, and Orrin Hatch as the only candidates still in the race.

On January 24, Bush won the Iowa caucuses with 41% of the vote. Forbes came in second with 30% of the vote. Keyes received 14%, Bauer 9%, McCain 5%, and Hatch 1%.[10] Two days later, Hatch dropped out and endorsed Bush.[11] The national media portrayed Bush as the establishment candidate.

With the support of many moderate Republicans and independents, McCain portrayed himself as a crusading insurgent who focused on campaign reform.[12]

On February 1, McCain, who had skipped the caucuses in order to divert resources toward New Hampshire and South Carolina, won a surprising 49–30% victory over Bush in the New Hampshire primary.[13] Bauer subsequently dropped out, followed by Forbes, who had won no primaries after spending $32 million of his own money on his campaign.[14] This left three candidates. In the South Carolina primary, Bush soundly defeated McCain.[15] Some McCain supporters accused the Bush campaign of mudslinging and negative campaigning, citing push polls that implied that McCain's adopted Bangladeshi-born daughter was an African-American child he fathered out of wedlock.[16] McCain's loss in South Carolina damaged his campaign, but he won both Michigan and his home state of Arizona on February 22.[17]

The primary campaigns impacted the South Carolina State House, where a controversy about the Confederate flag flying over the capitol dome prompted the state legislature to move the flag to a less prominent position at a Civil War memorial on the capitol grounds. Most GOP candidates said the issue should be left to South Carolina voters, but McCain later recanted and said the flag should be removed.[18]

McCain criticized Bush for speaking at and accepting the endorsement of Bob Jones University despite its policy banning interracial dating, actions for which Bush subsequently apologized.[19] On February 28, McCain also referred to Jerry Falwell and televangelist Pat Robertson as "agents of intolerance,"[20] a term from which he distanced himself during his 2008 bid. He lost Virginia to Bush on February 29.[21] On Super Tuesday, March 7, Bush won New York, Ohio, Georgia, Missouri, California, Maryland, and Maine. McCain won Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut, and Massachusetts but dropped out of the race. McCain became the Republican presidential nominee 8 years later, but lost the general election to Barack Obama. Bush took the majority of the remaining contests and won the Republican nomination on March 14, winning his home state of Texas and his brother Jeb's home state of Florida, among others. At the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, Bush accepted the nomination.

Bush asked former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney to head up a team to help select a running mate for him, but ultimately chose Cheney himself as the vice presidential nominee. While the U.S. Constitution does not specifically disallow a president and a vice president from the same state, it prohibits electors from casting both of their votes for persons from their own state. Accordingly, Cheney—who had been a resident of Texas for nearly 10 years—changed his voting registration back to Wyoming. Had Cheney not done this, either he or Bush would have forfeited his electoral votes from Texas.[22]

- Delegate totals

- Governor George W. Bush – 1,526

- Senator John McCain – 275

- Ambassador Alan Keyes – 23

- Businessman Steve Forbes – 10

- Gary Bauer – 2

- None of the names shown – 2

- Uncommitted – 1

Democratic Party nomination

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Vice President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

Vice presidential campaigns

|

||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Al Gore | Joe Lieberman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45th Vice President of the United States (1993–2001) |

U.S. Senator from Connecticut (1989–2013) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Withdrawn candidates

| Bill Bradley |

|---|

|

| U.S. Senator from New Jersey (1979–1997) |

|

| Campaign |

| W: March 9 3,027,912 votes |

Primary

Vice President Al Gore was a consistent front-runner for the nomination. Other prominent Democrats mentioned as possible contenders included Bob Kerrey,[23] Missouri Representative Dick Gephardt, Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone, and actor and director Warren Beatty.[24] Of these, only Wellstone formed an exploratory committee.[25]

Running an insurgency campaign, U.S. Senator Bill Bradley positioned himself as the alternative to Gore, who was a founding member of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council. While former basketball star Michael Jordan campaigned for him in the early primary states, Bradley announced his intention to campaign "in a different way" by conducting a positive campaign of "big ideas." His campaign's focus was a plan to spend the record-breaking budget surplus on a variety of social welfare programs to help the poor and the middle class, along with campaign finance reform and gun control.

Gore easily defeated Bradley in the primaries, largely because of support from the Democratic Party establishment and Bradley's poor showing in the Iowa caucus, where Gore successfully painted Bradley as aloof and indifferent to the plight of farmers. The closest Bradley came to a victory was his 50–46 loss to Gore in the New Hampshire primary. On March 14, Gore clinched the Democratic nomination.

None of Bradley's delegates were allowed to vote for him, so Gore won the nomination unanimously at the Democratic National Convention. Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman was nominated for vice president by voice vote. Lieberman became the first Jewish American ever to be chosen for this position by a major party. Gore chose Lieberman over five other finalists: Senators Evan Bayh, John Edwards, and John Kerry, House Minority Leader Dick Gephardt, and New Hampshire Governor Jeanne Shaheen.[26]

Delegate totals:

- Vice President Albert Gore Jr. – 4,328

- Abstentions – 9

Other nominations

Reform Party nomination

| 2000 Reform Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pat Buchanan | Ezola Foster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| White House Director of Communications (1985–1987) |

Conservative political activist | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Candidates in this section are sorted by date of withdrawal from the primaries | ||||||||

| John Hagelin | Donald Trump | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Leader of the Transcendental Meditation movement (1973–present) |

Chairman of The Trump Organization (1971–2017) | |||||||

| Campaign | Campaign | |||||||

| LN: July 01, 2000 28,539 votes |

W: February 14, 2000 0 votes | |||||||

The nomination went to Pat Buchanan[27] and running mate Ezola Foster from California over the objections of party founder Ross Perot and despite a rump convention nomination of John Hagelin by the Perot faction. In the end, the Federal Election Commission sided with Buchanan, and that ticket appeared on 49 of 51 possible ballots.[28]

Association of State Green Parties nomination

| |

|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Winona LaDuke |

| for President | for Vice President |

|

|

| Founder of Public Citizen |

Activist from Minnesota |

| |

- Green Party candidates:[29]

- Ralph Nader from Connecticut – 295

- Jello Biafra from California – 10

- Stephen Gaskin from Tennessee – 11

- Joel Kovel from New York – 3

- Abstain – 1

The Greens/Green Party USA, the then-recognized national party organization, later endorsed Nader for president and he appeared on the ballots of 43 states and Washington, D.C.

Libertarian Party nomination

- Libertarian Party candidates delegate totals:[30]

- Harry Browne from Tennessee – 493

- Don Gorman from New Hampshire – 166

- Jacob Hornberger from Virginia – 120

- Barry Hess from Arizona – 53

- None of the Above – 23

- other write-ins – 15

- David Hollist from California – 8

The Libertarian Party's National Nominating Convention nominated Harry Browne from Tennessee and Art Olivier from California for president and vice president. Browne was nominated on the first ballot and Olivier received the vice presidential nomination on the second ballot.[31] Browne appeared on every state ballot except Arizona's, due to a dispute between the Libertarian Party of Arizona (which instead nominated L. Neil Smith) and the national Libertarian Party.

Constitution Party nomination

- Constitution Party candidates:

- Howard Phillips

- Herb Titus

- Mathew Zupan

- Bob Smith U.S. Senator from New Hampshire (1990-2003)

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from NH-01 (1985-1990) Withdrew: August 17, 1999

The Constitution Party nominated Howard Phillips from Virginia for a third time and Curtis Frazier from Missouri. It was on the ballot in 41 states.[32]

Natural Law Party nomination

- John Hagelin from Iowa and Nat Goldhaber from California

The Natural Law Party held its national convention in Arlington County, Virginia, on August 31–September 2, unanimously nominating a ticket of Hagelin/Goldhaber without a roll-call vote.[33] The party was on 38 of the 51 ballots nationally.[32]

Independents

- Bob Smith U.S. Senator from New Hampshire (1990-2003)

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from NH-01 (1985-1990) Withdrew: October 28, 1999

General election campaign

Although the campaign focused mainly on domestic issues, such as the projected budget surplus, proposed reforms of Social Security and Medicare, health care, and competing plans for tax relief, foreign policy was often an issue.

Bush criticized the Clinton administration's policies in Somalia, where 18 Americans died in 1993 intervening among warring factions, and in the Balkans, where United States troops performed a variety of functions. "I don't think our troops ought to be used for what's called nation-building", Bush said in the second presidential debate.[34] Bush also pledged to bridge partisan gaps, claiming the atmosphere in Washington stood in the way of progress on necessary reforms.[35] Gore, meanwhile, questioned Bush's fitness for the job, pointing to gaffes Bush made in interviews and speeches and suggesting he lacked the necessary experience to be president.

Bill Clinton's impeachment and the sex scandal that led up to it cast a shadow on the campaign. Republicans strongly denounced the Clinton scandals, and Bush made a promise to restore "honor and dignity" to the White House a centerpiece of his campaign. Gore studiously avoided the Clinton scandals, as did Lieberman, even though Lieberman had been the first Democratic senator to denounce Clinton's misbehavior. Some observers theorized that Gore chose Lieberman in an attempt to separate himself from Clinton's past misdeeds and help blunt the GOP's attempts to link him to his boss.[36] Others pointed to the passionate kiss Gore gave his wife during the Democratic Convention as a signal that despite the allegations against Clinton, Gore himself was a faithful husband.[37] Gore avoided appearing with Clinton, who was shunted to low-visibility appearances in areas where he was popular. Experts have argued that this could have cost Gore votes from some of Clinton's core supporters.[38][39]

Ralph Nader was the most successful of the third-party candidates. His campaign was marked by a traveling tour of large "super-rallies" held in sports arenas like Madison Square Garden, with retired talk show host Phil Donahue as master of ceremonies.[40] After initially ignoring Nader, the Gore campaign made a pitch to potential Nader supporters in the campaign's final weeks,[41] downplaying his differences with Nader on the issues and arguing that Gore's ideas were more similar to Nader's than Bush's were and that Gore had a better chance of winning than Nader.[42] On the other side, the Republican Leadership Council ran pro-Nader ads in a few states in an effort to split the liberal vote.[43] Nader said his campaign's objective was to pass the 5-percent threshold so his Green Party would be eligible for matching funds in future races.[44]

Vice-presidential candidates Cheney and Lieberman campaigned aggressively. Both camps made numerous campaign stops nationwide, often just missing each other, such as when Cheney, Hadassah Lieberman, and Tipper Gore attended Chicago's Taste of Polonia over Labor Day Weekend.[45]

Presidential debates

| No. | Date | Host | City | Moderator | Participants | Viewership (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Tuesday, October 3, 2000 | University of Massachusetts Boston | Boston, Massachusetts | Jim Lehrer | Governor George W. Bush Vice President Al Gore |

46.6[46] |

| VP | Thursday, October 5, 2000 | Centre College | Danville, Kentucky | Bernard Shaw | Secretary Dick Cheney Senator Joe Lieberman |

28.5[46] |

| P2 | Wednesday, October 11, 2000 | Wake Forest University | Winston-Salem, North Carolina | Jim Lehrer | Governor George W. Bush Vice President Al Gore |

37.5[46] |

| P3 | Tuesday, October 17, 2000 | Washington University in St. Louis | St. Louis, Missouri | Jim Lehrer | Governor George W. Bush Vice President Al Gore |

37.7[46] |

After the 1996 presidential election, the Commission on Presidential Debates set new candidate selection criteria.[51] The new criteria required third-party candidates to poll at least 15% of the vote in national polls in order to take part in the CPD-sponsored presidential debates.[51] Nader was blocked from attending a closed-circuit screening of the first debate despite having a ticket,[52] and barred from attending an interview near the site of the third debate (Washington University in St. Louis) despite having a "perimeter pass".[53] Nader later sued the CPD for its role in the former incident. A settlement was reached that included an apology to him.[54]

Notable expressions and phrases

- Lockbox/Rainy Day fund: Gore's description of what he would do with the federal budget surplus, which was repeated many times in the first debate.

- Fuzzy math: a term used by Bush to dismiss the figures used by Gore. Others later turned the term against Bush.[55][56]

- Al Gore invented the Internet: an interpretation of Gore's having said he "took the initiative in creating the Internet," meaning that he was on the committee that funded the research leading to the Internet's formation.

- "Strategery": a phrase uttered by Saturday Night Live's Bush character (portrayed by Will Ferrell), which Bush staffers jokingly picked up to describe their operations.

Results

Ballot access

| Presidential ticket | Party | Ballot access | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gore / Lieberman | Democratic | 50+DC | 50,999,897 |

| Bush / Cheney | Republican | 50+DC | 50,456,002 |

| Nader / LaDuke | Green | 43+DC | 2,882,955 |

| Buchanan / Foster | Reform | 49 | 448,895 |

| Browne / Olivier | Libertarian | 49+DC★ | 384,431★ |

| Phillips / Frazier | Constitution | 41 | 98,020 |

| Hagelin / Goldhaber | Natural Law | 38 | 83,714 |

★Although the Libertarian Party had ballot access in all fifty United States plus D.C., Browne's name only appeared on the ballot in forty-nine United States plus D.C. The Libertarian Party of Arizona opted to place L. Neil Smith on the ballot in Browne's place. When adding Smith's 5,775 Arizona votes to Browne's 384,431 votes nationwide, that brings the total presidential votes cast for the Libertarian Party in 2000 to 390,206.

Florida recount

With the exceptions of Florida and Gore's home state of Tennessee, Bush carried the Southern states by comfortable margins, including Clinton's home state of Arkansas and also won Ohio, Indiana, most of the rural Midwestern farming states, most of the Rocky Mountain states, and Alaska. Gore balanced Bush by sweeping the Northeastern United States (with the exception of New Hampshire, which Bush won narrowly), the Pacific Coast states, Hawaii, New Mexico, and most of the Upper Midwest.

As the night wore on, the returns in a handful of small-to-medium-sized states, including Hawaii, Iowa, Oregon and New Mexico (Gore by 355 votes) were extremely close, but the election came down to Florida. As the final national results were tallied the following morning, Bush had clearly won 246 electoral votes and Gore 250, with 270 needed to win. Two smaller states—Wisconsin (11 electoral votes) and Oregon (7)—were still too close to call, but Florida's 25 electoral votes would be decisive regardless of their results. The election's outcome was not known for more than a month after voting ended because of the time required to count and recount Florida's ballots.

Between 7:50 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. EST on November 7, just before the polls closed in the largely Republican Florida panhandle, which is in the Central time zone, all major television news networks (CNN, NBC, FOX, CBS, and ABC) declared that Gore had won Florida. They based this prediction substantially on exit polls. But in the vote, Bush began to take a wide lead early in Florida, and by 10 p.m. EST, the networks had retracted their predictions and placed Florida back in the "undecided" column. At approximately 2:30 a.m. on November 8, with 85% of the vote counted in Florida and Bush leading Gore by more than 100,000 votes, the networks declared that Bush had carried Florida and therefore been elected president. But most of the remaining votes to be counted in Florida were in three heavily Democratic counties—Broward, Miami-Dade, and Palm Beach—and as their votes were reported Gore began to gain on Bush. By 4:30 a.m., after all votes were counted, Gore had narrowed Bush's margin to under 2,000 votes, and the networks retracted their declarations that Bush had won Florida and the presidency. Gore, who had privately conceded the election to Bush, withdrew his concession. The final result in Florida was slim enough to require a mandatory recount (by machine) under state law; Bush's lead dwindled to just over 300 votes when it was completed the day after the election. On November 8, Florida Division of Elections staff prepared a press release for Florida Secretary of State Katherine Harris that said overseas ballots must be "postmarked or signed and dated" by Election Day. It was never released.[7]: 16 A count of the overseas ballots later boosted Bush's margin to 930 votes. (According to a report by The New York Times, 680 of the accepted overseas ballots were received after the legal deadline, lacked required postmarks or a witness signature or address, or were unsigned or undated, cast after election day, from unregistered voters or voters not requesting ballots, or double-counted.[57])

Most of the post-electoral controversy revolved around Gore's request for hand recounts in four counties (Broward, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach, and Volusia), as provided under Florida state law. Harris, who also co-chaired Bush's Florida campaign, announced she would reject any revised totals from those counties if they were not turned in by 5 p.m. on November 14, the statutory deadline for amended returns. The Florida Supreme Court extended the deadline to November 26, a decision later vacated by the U.S. Supreme Court. Miami-Dade eventually halted its recount and resubmitted its original total to the state canvassing board, while Palm Beach County failed to meet the extended deadline, turning in its completed recount results at 7 p.m., which Harris rejected. On November 26, the state canvassing board certified Bush as the winner of Florida's electors by 537 votes. Gore formally contested the certified results. A state court decision overruling Gore was reversed by the Florida Supreme Court, which ordered a recount of over 70,000 ballots previously rejected as undervotes by machine counters. The U.S. Supreme Court halted that order the next day, with Justice Scalia issuing a concurring opinion that "the counting of votes that are of questionable legality does in my view threaten irreparable harm to petitioner" (Bush).[58]

On December 12, the Supreme Court ruled in Bush v. Gore a per curiam decision (asserted as a 7–2 vote) that the Florida Supreme Court's ruling requiring a statewide recount of ballots was unconstitutional on equal protection grounds, and in a 5–4 vote reversed and remanded the case to the Florida Supreme Court for modification before the optional "safe harbor" deadline, which the Supreme Court decided the Florida court had said the state intended to meet. With only two hours remaining until the December 12 deadline, the Supreme Court's order effectively ended the recount, and the previously certified total held.

Even if the Supreme Court had decided differently in Bush v. Gore, the Florida Legislature had been meeting in Special Session since December 8 with the purpose of selecting of a slate of electors on December 12 should the dispute still be ongoing.[59][60] Had the recount gone forward, it would have awarded those electors to Bush, based on the state-certified vote, and Gore's likely last recourse would have been to contest the electors in the United States Congress. The electors would then have been rejected only if both houses agreed to do so.[61]

National results

Though Gore came in second in the electoral vote, he received 543,895 more popular votes than Bush,[62] making him the first person since Grover Cleveland in 1888 to win the popular vote but lose in the Electoral College.[63] Gore failed to win the popular vote in his home state, Tennessee, which both he and his father had represented in the Senate, making him the first major-party presidential candidate to have lost his home state since George McGovern lost South Dakota in 1972. Furthermore, Gore lost West Virginia, a state that had voted Republican only once in the previous six presidential elections.[64]

Before the election, the possibility that different candidates would win the popular vote and the Electoral College had been noted, but usually with the expectation of Gore winning the Electoral College and Bush the popular vote.[65][66][67][68][69] The idea that Bush could win the Electoral College and Gore the popular vote was not considered likely.

This was the first time since 1928 when a non-incumbent Republican candidate won West Virginia. The Electoral College results were the closest since 1876, making this election the second-closest Electoral College result in history and the third-closest popular vote victory. Gore's 266 electoral votes are the highest for a losing nominee. The 537-vote margin in Florida is the closest for a tipping point state in history.[70] Bush was the first Republican since William McKinley to win with under 300 electoral votes. He was also the first son of a former president to be elected president himself since John Quincy Adams in 1824.

Bush was the first Republican in American history to win the presidency without carrying Vermont, Illinois, or New Mexico, as well as the second Republican to win the presidency without carrying California after James A. Garfield in 1880, and Pennsylvania, Maine, and Michigan after Richard Nixon in 1968, as well as the first winning Republican not to receive any electoral votes from California as Garfield received one electoral vote in 1880. Bush was the first Republican to win without New Jersey, Delaware, or Connecticut since 1888. As of 2020, Bush is the last Republican nominee to win New Hampshire. No state in the Northeast has voted Republican since except for Pennsylvania in 2016. This marked the first time since Iowa entered the union in 1846 in which the state voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in four elections in a row and the last time until 2020 that Iowa did not vote for the overall winner. This election was the first time since 1976 that New Jersey, Connecticut, Vermont, Maine, Illinois, New Mexico, Michigan, and California voted for the losing candidate, as well as the first since 1980 that Maryland did so, the first since 1948 that Delaware did so, and the first since 1968 that Pennsylvania did so.

There were only two counties in the nation that had voted Republican in 1996 and flipped to the Democratic column in 2000: Charles County, Maryland, and Orange County, Florida, both rapidly diversifying counties.[71] The 2000 election was also the last time a Republican won a number of populous urban counties that have since turned into Democratic strongholds. These include Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (Charlotte); Marion County, Indiana (Indianapolis), Fairfax County, Virginia (DC suburbs), Chatham County, Georgia (Savannah), Whatcom County, Washington (Bellingham), and Travis County, Texas (Austin). Conversely, as of 2020, Gore is the last Democrat to have won any counties at all in Oklahoma.[72]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| George W. Bush | Republican | Texas | 50,456,002 | 47.86% | 271 | Dick Cheney | Wyoming | 271 |

| Al Gore | Democratic | Tennessee | 50,999,897 | 48.38% | 266 | Joe Lieberman | Connecticut | 266 |

| Ralph Nader | Green | Connecticut | 2,882,955 | 2.74% | 0 | Winona LaDuke | Minnesota | 0 |

| Pat Buchanan | Reform | Virginia | 448,895 | 0.43% | 0 | Ezola Foster | California | 0 |

| Harry Browne | Libertarian | Tennessee | 384,431 | 0.36% | 0 | Art Olivier | California | 0 |

| Howard Phillips | Constitution | Virginia | 98,020 | 0.09% | 0 | Curtis Frazier | Missouri | 0 |

| John Hagelin | Natural Law | Iowa | 83,714 | 0.08% | 0 | Nat Goldhaber | California | 0 |

| Other | 51,186 | 0.05% | — | Other | — | |||

| (abstention)[c] | — | — | — | — | 1 | (abstention)[c] | — | 1 |

| Total | 105,421,423 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

- Source: "2000 Presidential Electoral and Popular Vote" (Excel 4.0). Federal Election Commission.

-

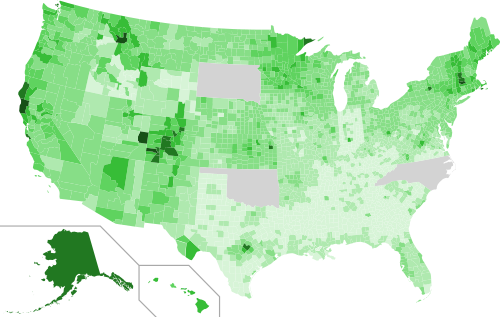

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote.

-

Results by congressional district, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote.

-

Vote share by county for Green Party candidate Ralph Nader. Darker shades indicate a stronger Green performance.

-

Election results by county.

-

Election results by congressional district.

Results by state

| States/districts won by Gore/Lieberman | |

| States/districts won by Bush/Cheney | |

| † | At-large results (For states that split electoral votes) |

| George W. Bush Republican |

Al Gore Democratic |

Ralph Nader Green |

Pat Buchanan Reform |

Harry Browne Libertarian |

Howard Phillips Constitution |

John Hagelin Natural Law |

Others | Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | # | |

| Alabama | 9 | 941,173 | 56.48% | 9 | 692,611 | 41.57% | – | 18,323 | 1.10% | – | 6,351 | 0.38% | – | 5,893 | 0.35% | – | 775 | 0.05% | – | 447 | 0.03% | – | 699 | 0.04% | – | 248,562 | 14.92% | 1,666,272 | AL |

| Alaska | 3 | 167,398 | 58.62% | 3 | 79,004 | 27.67% | – | 28,747 | 10.07% | – | 5,192 | 1.82% | – | 2,636 | 0.92% | – | 596 | 0.21% | – | 919 | 0.32% | – | 1,068 | 0.37% | – | 88,394 | 30.95% | 285,560 | AK |

| Arizona* | 8 | 781,652 | 51.02% | 8 | 685,341 | 44.73% | – | 45,645 | 2.98% | – | 12,373 | 0.81% | – | – | – | – | 110 | 0.01% | – | 1,120 | 0.07% | – | 5,775 | 0.38% | – | 96,311 | 6.29% | 1,532,016 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 6 | 472,940 | 51.31% | 6 | 422,768 | 45.86% | – | 13,421 | 1.46% | – | 7,358 | 0.80% | – | 2,781 | 0.30% | – | 1,415 | 0.15% | – | 1,098 | 0.12% | – | – | – | – | 50,172 | 5.44% | 921,781 | AR |

| California | 54 | 4,567,429 | 41.65% | – | 5,861,203 | 53.45% | 54 | 418,707 | 3.82% | – | 44,987 | 0.41% | – | 45,520 | 0.42% | – | 17,042 | 0.16% | – | 10,934 | 0.10% | – | 34 | 0.00% | – | −1,293,774 | −11.80% | 10,965,856 | CA |

| Colorado | 8 | 883,748 | 50.75% | 8 | 738,227 | 42.39% | – | 91,434 | 5.25% | – | 10,465 | 0.60% | – | 12,799 | 0.73% | – | 1,319 | 0.08% | – | 2,240 | 0.13% | – | 1,136 | 0.07% | – | 145,521 | 8.36% | 1,741,368 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 561,094 | 38.44% | – | 816,015 | 55.91% | 8 | 64,452 | 4.42% | – | 4,731 | 0.32% | – | 3,484 | 0.24% | – | 9,695 | 0.66% | – | 40 | 0.00% | – | 14 | 0.00% | – | −254,921 | −17.47% | 1,459,525 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 137,288 | 41.90% | – | 180,068 | 54.96% | 3 | 8,307 | 2.54% | – | 777 | 0.24% | – | 774 | 0.24% | – | 208 | 0.06% | – | 107 | 0.03% | – | 93 | 0.03% | – | −42,780 | −13.06% | 327,622 | DE |

| D.C. | 3 | 18,073 | 8.95% | – | 171,923 | 85.16% | 2 | 10,576 | 5.24% | – | – | – | – | 669 | 0.33% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 653 | 0.32% | 1 | −153,850 | −76.20% | 201,894 | DC |

| Florida | 25 | 2,912,790 | 48.85% | 25 | 2,912,253 | 48.84% | – | 97,488 | 1.63% | – | 17,484 | 0.29% | – | 16,415 | 0.28% | – | 1,371 | 0.02% | – | 2,281 | 0.04% | – | 3,028 | 0.05% | – | 537 | 0.01% | 5,963,110 | FL |

| Georgia | 13 | 1,419,720 | 54.67% | 13 | 1,116,230 | 42.98% | – | 13,432 | 0.52% | – | 10,926 | 0.42% | – | 36,332 | 1.40% | – | 140 | 0.01% | – | – | – | – | 24 | 0.00% | – | 303,490 | 11.69% | 2,596,804 | GA |

| Hawaii | 4 | 137,845 | 37.46% | – | 205,286 | 55.79% | 4 | 21,623 | 5.88% | – | 1,071 | 0.29% | – | 1,477 | 0.40% | – | 343 | 0.09% | – | 306 | 0.08% | – | – | – | – | −67,441 | −18.33% | 367,951 | HI |

| Idaho | 4 | 336,937 | 67.17% | 4 | 138,637 | 27.64% | – | 12,292 | 2.45% | – | 7,615 | 1.52% | – | 3,488 | 0.70% | – | 1,469 | 0.29% | – | 1,177 | 0.23% | – | 6 | 0.00% | – | 198,300 | 39.53% | 501,621 | ID |

| Illinois | 22 | 2,019,421 | 42.58% | – | 2,589,026 | 54.60% | 22 | 103,759 | 2.19% | – | 16,106 | 0.34% | – | 11,623 | 0.25% | – | 57 | 0.00% | – | 2,127 | 0.04% | – | 4 | 0.00% | – | −569,605 | −12.01% | 4,742,123 | IL |

| Indiana | 12 | 1,245,836 | 56.65% | 12 | 901,980 | 41.01% | – | 18,531 | 0.84% | – | 16,959 | 0.77% | – | 15,530 | 0.71% | – | 200 | 0.01% | – | 167 | 0.01% | – | 99 | 0.00% | – | 343,856 | 15.63% | 2,199,302 | IN |

| Iowa | 7 | 634,373 | 48.22% | – | 638,517 | 48.54% | 7 | 29,374 | 2.23% | – | 5,731 | 0.44% | – | 3,209 | 0.24% | – | 613 | 0.05% | – | 2,281 | 0.17% | – | 1,465 | 0.11% | – | −4,144 | −0.31% | 1,315,563 | IA |

| Kansas | 6 | 622,332 | 58.04% | 6 | 399,276 | 37.24% | – | 36,086 | 3.37% | – | 7,370 | 0.69% | – | 4,525 | 0.42% | – | 1,254 | 0.12% | – | 1,375 | 0.13% | – | – | – | – | 223,056 | 20.80% | 1,072,218 | KS |

| Kentucky | 8 | 872,492 | 56.50% | 8 | 638,898 | 41.37% | – | 23,192 | 1.50% | – | 4,173 | 0.27% | – | 2,896 | 0.19% | – | 923 | 0.06% | – | 1,533 | 0.10% | – | 80 | 0.01% | – | 233,594 | 15.13% | 1,544,187 | KY |

| Louisiana | 9 | 927,871 | 52.55% | 9 | 792,344 | 44.88% | – | 20,473 | 1.16% | – | 14,356 | 0.81% | – | 2,951 | 0.17% | – | 5,483 | 0.31% | – | 1,075 | 0.06% | – | 1,103 | 0.06% | – | 135,527 | 7.68% | 1,765,656 | LA |

| Maine† | 2 | 286,616 | 43.97% | – | 319,951 | 49.09% | 2 | 37,127 | 5.70% | – | 4,443 | 0.68% | – | 3,074 | 0.47% | – | 579 | 0.09% | – | – | – | – | 27 | 0.00% | – | −33,335 | −5.11% | 651,817 | ME |

| Maine-1 | 1 | 148,618 | 42.59% | – | 176,293 | 50.52% | 1 | 20,297 | 5.82% | – | 1,994 | 0.57% | – | 1,479 | 0.42% | – | 253 | 0.07% | – | – | – | – | 17 | 0.00% | – | –27,675 | –7.93% | 348,951 | ME1 |

| Maine-2 | 1 | 137,998 | 45.56% | – | 143,658 | 47.43% | 1 | 16,830 | 5.56% | – | 2,449 | 0.81% | – | 1,595 | 0.53% | – | 326 | 0.11% | – | – | – | – | 10 | 0.00% | – | –5,660 | –1.87% | 302,866 | ME2 |

| Maryland | 10 | 813,797 | 40.18% | – | 1,145,782 | 56.57% | 10 | 53,768 | 2.65% | – | 4,248 | 0.21% | – | 5,310 | 0.26% | – | 919 | 0.05% | – | 176 | 0.01% | – | 1,480 | 0.07% | – | −331,985 | −16.39% | 2,025,480 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 12 | 878,502 | 32.50% | – | 1,616,487 | 59.80% | 12 | 173,564 | 6.42% | – | 11,149 | 0.41% | – | 16,366 | 0.61% | – | – | – | – | 2,884 | 0.11% | – | 4,032 | 0.15% | – | −737,985 | −27.30% | 2,702,984 | MA |

| Michigan | 18 | 1,953,139 | 46.15% | – | 2,170,418 | 51.28% | 18 | 84,165 | 1.99% | – | 1,851 | 0.04% | – | 16,711 | 0.39% | – | 3,791 | 0.09% | – | 2,426 | 0.06% | – | – | – | – | −217,279 | −5.13% | 4,232,501 | MI |

| Minnesota | 10 | 1,109,659 | 45.50% | – | 1,168,266 | 47.91% | 10 | 126,696 | 5.20% | – | 22,166 | 0.91% | – | 5,282 | 0.22% | – | 3,272 | 0.13% | – | 2,294 | 0.09% | – | 1,050 | 0.04% | – | −58,607 | −2.40% | 2,438,685 | MN |

| Mississippi | 7 | 572,844 | 57.62% | 7 | 404,614 | 40.70% | – | 8,122 | 0.82% | – | 2,265 | 0.23% | – | 2,009 | 0.20% | – | 3,267 | 0.33% | – | 450 | 0.05% | – | 613 | 0.06% | – | 168,230 | 16.92% | 994,184 | MS |

| Missouri | 11 | 1,189,924 | 50.42% | 11 | 1,111,138 | 47.08% | – | 38,515 | 1.63% | – | 9,818 | 0.42% | – | 7,436 | 0.32% | – | 1,957 | 0.08% | – | 1,104 | 0.05% | – | – | – | – | 78,786 | 3.34% | 2,359,892 | MO |

| Montana | 3 | 240,178 | 58.44% | 3 | 137,126 | 33.36% | – | 24,437 | 5.95% | – | 5,697 | 1.39% | – | 1,718 | 0.42% | – | 1,155 | 0.28% | – | 675 | 0.16% | – | 11 | 0.00% | – | 103,052 | 25.07% | 410,997 | MT |

| Nebraska† | 2 | 433,862 | 62.25% | 2 | 231,780 | 33.25% | – | 24,540 | 3.52% | – | 3,646 | 0.52% | – | 2,245 | 0.32% | – | 468 | 0.07% | – | 478 | 0.07% | – | – | – | – | 202,082 | 28.99% | 697,019 | NE |

| Nebraska-1 | 1 | 142,562 | 58.90% | 1 | 86,946 | 35.92% | – | 10,085 | 4.17% | – | 1,324 | 0.55% | – | 754 | 0.31% | – | 167 | 0.07% | – | 185 | 0.08% | – | – | – | – | 55,616 | 22.98% | 242,023 | NE1 |

| Nebraska-2 | 1 | 131,485 | 56.92% | 1 | 88,975 | 38.52% | – | 8,495 | 3.68% | – | 845 | 0.37% | – | 925 | 0.40% | – | 146 | 0.06% | – | 141 | 0.06% | – | – | – | – | 42,510 | 18.40% | 231,012 | NE2 |

| Nebraska-3 | 1 | 159,815 | 71.35% | 1 | 55,859 | 24.94% | – | 5,960 | 2.66% | – | 1,477 | 0.66% | – | 566 | 0.25% | – | 155 | 0.07% | – | 152 | 0.07% | – | – | – | – | 103,956 | 46.41% | 223,984 | NE3 |

| Nevada | 4 | 301,575 | 49.52% | 4 | 279,978 | 45.98% | – | 15,008 | 2.46% | – | 4,747 | 0.78% | – | 3,311 | 0.54% | – | 621 | 0.10% | – | 415 | 0.07% | – | 3,315 | 0.54% | – | 21,597 | 3.55% | 608,970 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 273,559 | 48.07% | 4 | 266,348 | 46.80% | – | 22,198 | 3.90% | – | 2,615 | 0.46% | – | 2,757 | 0.48% | – | 328 | 0.06% | – | 55 | 0.01% | – | 1,221 | 0.21% | – | 7,211 | 1.27% | 569,081 | NH |

| New Jersey | 15 | 1,284,173 | 40.29% | – | 1,788,850 | 56.13% | 15 | 94,554 | 2.97% | – | 6,989 | 0.22% | – | 6,312 | 0.20% | – | 1,409 | 0.04% | – | 2,215 | 0.07% | – | 2,724 | 0.09% | – | −504,677 | −15.83% | 3,187,226 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 5 | 286,417 | 47.85% | – | 286,783 | 47.91% | 5 | 21,251 | 3.55% | – | 1,392 | 0.23% | – | 2,058 | 0.34% | – | 343 | 0.06% | – | 361 | 0.06% | – | – | – | – | −366 | −0.06% | 598,605 | NM |

| New York | 33 | 2,403,374 | 35.23% | – | 4,107,697 | 60.21% | 33 | 244,030 | 3.58% | – | 31,599 | 0.46% | – | 7,649 | 0.11% | – | 1,498 | 0.02% | – | 24,361 | 0.36% | – | 1,791 | 0.03% | – | −1,704,323 | −24.98% | 6,821,999 | NY |

| North Carolina | 14 | 1,631,163 | 56.03% | 14 | 1,257,692 | 43.20% | – | – | – | – | 8,874 | 0.30% | – | 12,307 | 0.42% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,226 | 0.04% | – | 373,471 | 12.83% | 2,911,262 | NC |

| North Dakota | 3 | 174,852 | 60.66% | 3 | 95,284 | 33.06% | – | 9,486 | 3.29% | – | 7,288 | 2.53% | – | 660 | 0.23% | – | 373 | 0.13% | – | 313 | 0.11% | – | – | – | – | 79,568 | 27.60% | 288,256 | ND |

| Ohio | 21 | 2,351,209 | 49.97% | 21 | 2,186,190 | 46.46% | – | 117,857 | 2.50% | – | 26,724 | 0.57% | – | 13,475 | 0.29% | – | 3,823 | 0.08% | – | 6,169 | 0.13% | – | 10 | 0.00% | – | 165,019 | 3.51% | 4,705,457 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 744,337 | 60.31% | 8 | 474,276 | 38.43% | – | – | – | – | 9,014 | 0.73% | – | 6,602 | 0.53% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 270,061 | 21.88% | 1,234,229 | OK |

| Oregon | 7 | 713,577 | 46.52% | – | 720,342 | 46.96% | 7 | 77,357 | 5.04% | – | 7,063 | 0.46% | – | 7,447 | 0.49% | – | 2,189 | 0.14% | – | 2,574 | 0.17% | – | 3,419 | 0.22% | – | −6,765 | −0.44% | 1,533,968 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 23 | 2,281,127 | 46.43% | – | 2,485,967 | 50.60% | 23 | 103,392 | 2.10% | – | 16,023 | 0.33% | – | 11,248 | 0.23% | – | 14,428 | 0.29% | – | – | – | – | 934 | 0.02% | – | −204,840 | −4.17% | 4,913,119 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 130,555 | 31.91% | – | 249,508 | 60.99% | 4 | 25,052 | 6.12% | – | 2,273 | 0.56% | – | 742 | 0.18% | – | 97 | 0.02% | – | 271 | 0.07% | – | 614 | 0.15% | – | −118,953 | −29.08% | 409,112 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 785,937 | 56.84% | 8 | 565,561 | 40.90% | – | 20,200 | 1.46% | – | 3,519 | 0.25% | – | 4,876 | 0.35% | – | 1,682 | 0.12% | – | 942 | 0.07% | – | – | – | – | 220,376 | 15.94% | 1,382,717 | SC |

| South Dakota | 3 | 190,700 | 60.30% | 3 | 118,804 | 37.56% | – | – | – | – | 3,322 | 1.05% | – | 1,662 | 0.53% | – | 1,781 | 0.56% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 71,896 | 22.73% | 316,269 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 1,061,949 | 51.15% | 11 | 981,720 | 47.28% | – | 19,781 | 0.95% | – | 4,250 | 0.20% | – | 4,284 | 0.21% | – | 1,015 | 0.05% | – | 613 | 0.03% | – | 2,569 | 0.12% | – | 80,229 | 3.86% | 2,076,181 | TN |

| Texas | 32 | 3,799,639 | 59.30% | 32 | 2,433,746 | 37.98% | – | 137,994 | 2.15% | – | 12,394 | 0.19% | – | 23,160 | 0.36% | – | 567 | 0.01% | – | – | – | – | 137 | 0.00% | – | 1,365,893 | 21.32% | 6,407,637 | TX |

| Utah | 5 | 515,096 | 66.83% | 5 | 203,053 | 26.34% | – | 35,850 | 4.65% | – | 9,319 | 1.21% | – | 3,616 | 0.47% | – | 2,709 | 0.35% | – | 763 | 0.10% | – | 348 | 0.05% | – | 312,043 | 40.49% | 770,754 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 119,775 | 40.70% | – | 149,022 | 50.63% | 3 | 20,374 | 6.92% | – | 2,192 | 0.74% | – | 784 | 0.27% | – | 153 | 0.05% | – | 219 | 0.07% | – | 1,789 | 0.61% | – | −29,247 | −9.94% | 294,308 | VT |

| Virginia | 13 | 1,437,490 | 52.47% | 13 | 1,217,290 | 44.44% | – | 59,398 | 2.17% | – | 5,455 | 0.20% | – | 15,198 | 0.55% | – | 1,809 | 0.07% | – | 171 | 0.01% | – | 2,636 | 0.10% | – | 220,200 | 8.04% | 2,739,447 | VA |

| Washington | 11 | 1,108,864 | 44.58% | – | 1,247,652 | 50.16% | 11 | 103,002 | 4.14% | – | 7,171 | 0.29% | – | 13,135 | 0.53% | – | 1,989 | 0.08% | – | 2,927 | 0.12% | – | 2,693 | 0.11% | – | −138,788 | −5.58% | 2,487,433 | WA |

| West Virginia | 5 | 336,475 | 51.92% | 5 | 295,497 | 45.59% | – | 10,680 | 1.65% | – | 3,169 | 0.49% | – | 1,912 | 0.30% | – | 23 | 0.00% | – | 367 | 0.06% | – | 1 | 0.00% | – | 40,978 | 6.32% | 648,124 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 11 | 1,237,279 | 47.61% | – | 1,242,987 | 47.83% | 11 | 94,070 | 3.62% | – | 11,471 | 0.44% | – | 6,640 | 0.26% | – | 2,042 | 0.08% | – | 853 | 0.03% | – | 3,265 | 0.13% | – | −5,708 | −0.22% | 2,598,607 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 147,947 | 67.76% | 3 | 60,481 | 27.70% | – | 4,625 | 2.12% | – | 2,724 | 1.25% | – | 1,443 | 0.66% | – | 720 | 0.33% | – | 411 | 0.19% | – | – | – | – | 87,466 | 40.06% | 218,351 | WY |

| Totals† | 538 | 50,456,002 | 47.86% | 271 | 50,999,897 | 48.38% | 267 | 2,882,955 | 2.74% | – | 448,895 | 0.43% | – | 384,431* | 0.36%* | – | 98,020 | 0.09% | – | 83,714 | 0.08% | – | 51,186 | 0.05% | – | −543,895 | −0.52% | 105,405,100 | US |

†Maine and Nebraska each allow for their electoral votes to be split between candidates. In both states, two electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the statewide race and one electoral vote is awarded to the winner of each congressional district. The votes for each candidate are only singly counted in the column totals.[74][75]

*The Libertarian Party of Arizona had ballot access but opted to supplant Browne with L. Neil Smith. In Arizona, Smith received 5,775 votes, or 0.38% of the Arizona vote. Adding Smith's 5,775 votes to Browne's 384,431 votes nationwide, the total votes cast for president for the Libertarian Party in 2000 was 390,206, or 0.37% of the national vote.

States that flipped from Democratic to Republican

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- Florida

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Missouri

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- Ohio

- Tennessee

- West Virginia

Close states

States where the margin of victory was less than 1% (55 electoral votes):[76]

- Florida, 0.009% (537 votes) (tipping point state)

- New Mexico, 0.061% (366 votes)

- Wisconsin, 0.22% (5,708 votes)

- Iowa, 0.31% (4,144 votes)

- Oregon, 0.44% (6,765 votes)

States where the margin of victory was more than 1% but less than 5% (84 electoral votes):

- New Hampshire, 1.27% (7,211 votes)

- Maine's 2nd Congressional District, 1.87% (5,660 votes)

- Minnesota, 2.40% (58,607 votes)

- Missouri, 3.34% (78,786 votes)

- Ohio, 3.51% (165,019 votes)

- Nevada, 3.55% (21,597 votes)

- Tennessee, 3.86% (80,229 votes)

- Pennsylvania, 4.17% (204,840 votes)

States where the margin of victory was more than 5% but less than 10% (84 electoral votes):

- Maine, 5.11% (33,335 votes)

- Michigan, 5.13% (217,279 votes)

- Arkansas, 5.44% (50,172 votes)

- Washington, 5.58% (138,788 votes)

- Arizona, 6.29% (96,311 votes)

- West Virginia, 6.32% (40,978 votes)

- Louisiana, 7.68% (135,527 votes)

- Maine's 1st Congressional District, 7.93% (27,675 votes)

- Virginia, 8.04% (220,200 votes)

- Colorado, 8.36% (145,518 votes)

- Vermont, 9.94% (29,247 votes)

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Glasscock County, Texas 92.47%

- Ochiltree County, Texas 90.72%

- Hansford County, Texas 89.75%

- Harding County, South Dakota 88.92%

- Carter County, Montana 88.84%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Macon County, Alabama 86.80%

- Bronx County, New York 86.28%

- Shannon County, South Dakota 85.36%

- Washington, D.C. 85.16%

- City of Baltimore, Maryland 82.52%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

- San Miguel County, Colorado 17.20%

- Missoula County, Montana 15.03%

- Grand County, Utah 14.94%

- Mendocino County, California 14.68%

- Hampshire County, Massachusetts 14.59%

Voter demographics

| Demographic subgroup | Gore | Bush | Other | % of total vote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total vote | 48 | 48 | 4 | 100 |

| Ideology | ||||

| Liberals | 81 | 13 | 6 | 20 |

| Moderates | 53 | 45 | 2 | 50 |

| Conservatives | 17 | 82 | 1 | 29 |

| Party | ||||

| Democrats | 87 | 11 | 2 | 39 |

| Republicans | 8 | 91 | 1 | 35 |

| Independents | 46 | 48 | 6 | 26 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 43 | 54 | 3 | 48 |

| Women | 54 | 44 | 2 | 52 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 42 | 55 | 3 | 81 |

| Black | 90 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Asian | 55 | 41 | 4 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 62 | 35 | 3 | 7 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 years old | 47 | 47 | 6 | 9 |

| 25–29 years old | 49 | 46 | 5 | 8 |

| 30–49 years old | 48 | 50 | 2 | 45 |

| 50–64 years old | 50 | 48 | 2 | 24 |

| 65 and older | 51 | 47 | 2 | 14 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 71 | 25 | 4 | 4 |

| Heterosexual | 47 | 50 | 3 | 96 |

| Family income | ||||

| Under $15,000 | 58 | 38 | 4 | 7 |

| $15,000–30,000 | 54 | 42 | 4 | 16 |

| $30,000–50,000 | 49 | 48 | 3 | 24 |

| $50,000–75,000 | 46 | 51 | 3 | 25 |

| $75,000–100,000 | 46 | 52 | 2 | 13 |

| Over $100,000 | 43 | 55 | 2 | 15 |

| Region | ||||

| East | 56 | 40 | 4 | 23 |

| Midwest | 48 | 49 | 3 | 26 |

| South | 43 | 56 | 1 | 31 |

| West | 49 | 47 | 4 | 20 |

| Union households | ||||

| Union | 59 | 37 | 4 | 26 |

| Non-union | 45 | 53 | 2 | 74 |

Source: Voter News Service exit poll from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (13,225 surveyed)[78]

Aftermath

After Florida was decided and Gore conceded, Texas Governor George W. Bush became the president-elect and began forming his transition committee.[79] In a speech on December 13, in the Texas House of Representatives chamber,[80] Bush stated he was reaching across party lines to bridge a divided America, saying, "the President of the United States is the President of every single American, of every race, and every background."[81]

Post-recount

On January 6, 2001, a joint session of Congress met to certify the electoral vote. Twenty members of the House of Representatives, most of them members of the all-Democratic Congressional Black Caucus, rose one by one to file objections to the electoral votes of Florida. But pursuant to the Electoral Count Act, any such objection had to be sponsored by both a representative and a senator. No senator co-sponsored these objections, deferring to the Supreme Court's ruling. Therefore, Gore, who presided in his capacity as President of the Senate, ruled each of these objections out of order.[82] Subsequently, the joint session of Congress on January 7, 2001, certified the electoral votes from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.[83]

Bush took the oath of office on January 20, 2001. He served for the next eight years. Gore has not, as of 2024, considered another presidential run, endorsing Howard Dean's candidacy during the 2004 Democratic primary and remaining neutral in the Democratic primaries of 2008, 2016 and 2020.[84][85][86][87][88]

The first independent recount of undervotes was conducted by the Miami Herald and USA Today. The commission found that under most scenarios for completion of the initiated recounts, Bush would have won the election, but Gore would have won using the most generous standards for undervotes.[89]

Ultimately, a media consortium—comprising The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Tribune Co. (parent of the Los Angeles Times), Associated Press, CNN, The Palm Beach Post and the St. Petersburg Times[90]—hired NORC at the University of Chicago[91] to examine 175,010 ballots collected from the entire state, not just the disputed counties that were recounted; these ballots contained undervotes (ballots with no machine-detected choice made for president) and overvotes (ballots with more than one choice marked). Their goal was to determine the reliability and accuracy of the systems used for the voting process. Based on the NORC review, the media group concluded that if the disputes over all the ballots in question had been resolved by applying statewide any of five standards that would have met Florida's legal standard for recounts, the electoral result would have been reversed and Gore would have won by 60 to 171 votes. (Any analysis of NORC data requires, for each punch ballot, at least two of the three ballot reviewers' codes to agree or instead, for all three to agree.) For all undervotes and overvotes statewide, these five standards are:[7][92][93]

- Prevailing standard – accepts at least one detached corner of a chad and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

- County-by-county standard – applies each county's own standards independently.

- Two-corner standard – accepts at least two detached corners of a chad and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

- Most restrictive standard – accepts only so-called perfect ballots that machines somehow missed and did not count, or ballots with unambiguous expressions of voter intent.

- Most inclusive standard – applies uniform criteria of "dimple or better" on punch marks and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

Such a statewide review including all uncounted votes was a tangible possibility, as Leon County Circuit Court Judge Terry Lewis, whom the Florida Supreme Court had assigned to oversee the statewide recount, had scheduled a hearing for December 13 (mooted by the U.S. Supreme Court's final ruling on the 12th) to consider the question of including overvotes as well as undervotes. Subsequent statements by Lewis and internal court documents support the likelihood of including overvotes in the recount.[94] Florida State University professor of public policy Lance deHaven-Smith observed that, even considering only undervotes, "under any of the five most reasonable interpretations of the Florida Supreme Court ruling, Gore does, in fact, more than make up the deficit".[7] Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting's analysis of the NORC study and media coverage of it supports these interpretations and criticizes the coverage of the study by media outlets such as The New York Times and the other media consortium members.[90]

Further, according to sociologists Christopher Uggen and Jeff Manza, the 2000 election might have gone to Gore if the disenfranchised population of Florida had voted. Florida law disenfranchises convicted felons, requiring individual applications to regain suffrage. In a 2002 American Sociological Review article, Uggen and Manza found that the released felon vote could have altered the outcome of seven senatorial races between 1978 and 2000, and the 2000 presidential election.[95] Matt Ford noted their study concluded, "if the state's 827,000 disenfranchised felons had voted at the same rate as other Floridians, Democratic candidate Al Gore would have won Florida—and the presidency—by more than 80,000 votes."[96] The effect of Florida's law is such that in 2014, purportedly "[m]ore than one in ten Floridians—and nearly one in four African-American Floridians—are shut out of the polls because of felony convictions."[97]

Voting machines

Because the 2000 presidential election was so close in Florida, the federal government and state governments pushed for election reform to be prepared by the 2004 presidential election. Many of Florida's 2000 election night problems stemmed from usability and ballot design factors with voting systems, including the potentially confusing "butterfly ballot." Many voters had difficulties with the paper-based punch card voting machines and were either unable to understand the voting process or unable to perform it. This resulted in an unusual number of overvotes (voting for more candidates than is allowed) and undervotes (voting for fewer than the minimum candidates, including none at all). Many undervotes were caused by voter error, unmaintained punch card voting booths, or errors having to do merely with the characteristics of punch card ballots (resulting in hanging, dimpled, or pregnant chads).

A proposed solution to these problems was the installation of modern electronic voting machines. The 2000 presidential election spurred the debate about election and voting reform but did not end it.

In the aftermath of the election, the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) was passed to help states upgrade their election technology in the hopes of preventing similar problems in future elections. But the electronic voting systems that many states purchased to comply with HAVA actually caused problems in the 2004 presidential election.[98]

Exit polling and declaration of vote winners

The Voter News Service's reputation was damaged by its treatment of Florida's presidential vote in 2000. Breaking its own guidelines,[citation needed] VNS called the state as a win for Gore 12 minutes before polls closed in the Florida Panhandle. Although most of the state is in the Eastern Time Zone, counties in the Panhandle, in the Central Time Zone, had not yet closed their polls. Discrepancies between the results of exit polls and the actual vote count caused the VNS to change its call twice, first from Gore to Bush and then to "too close to call." Due in part to this (and other polling inaccuracies) the VNS was disbanded in 2003.[99]

According to Bush adviser Karl Rove, exit polls early in the afternoon on election day showed Gore winning by three percentage points, but when the networks called the state for Gore, Bush led by about 75,000 votes in raw tallies from the Florida Secretary of State.

Charges of media bias were leveled against the networks by Republicans, who claimed that the networks called states more quickly for Al Gore than for George W. Bush. Congress held hearings on this matter,[100] at which the networks claimed to have no intentional bias in their election night reporting. A study of the calls made on election night 2000 indicated that states carried by Gore were called more quickly than states won by Bush;[101] however, notable states carried by Bush, such as New Hampshire and Florida, were very close, and close states won by Gore, such as Iowa, Oregon, New Mexico and Wisconsin, were called late as well.[102]

The early call of Florida for Gore has been alleged to have cost Bush several close states, including Iowa, New Mexico, Oregon, and Wisconsin.[citation needed] In each of these states, Gore won by less than 10,000 votes, and the polls closed after the networks called Florida for Gore. Because the Florida call was widely seen as an indicator that Gore had won the election, it is possible that it depressed Republican turnout in these states during the final hours of voting, giving Gore the slim margin by which he carried each of them.[citation needed] The call may have also affected the outcome of the Senate election in Washington state, where incumbent Republican Slade Gorton was defeated by approximately 2,000 votes.[citation needed]

Ralph Nader "spoiler" controversy

Many Gore supporters claimed that third-party candidate Nader acted as a spoiler in the election, under the presumption that Nader voters would have voted for Gore had Nader not been in the race.[103] Nader received 2.74 percent of the popular vote nationwide, getting 97,000 votes in Florida (by comparison, there were 111,251 overvotes)[104][105] and 22,000 votes in New Hampshire, where Bush beat Gore by 7,000 votes. Winning either state would have won the general election for Gore. Defenders of Nader, including Dan Perkins, argued that the margin in Florida was small enough that Democrats could blame any number of third-party candidates for the defeat, including Workers World Party candidate Monica Moorehead, who received 1,500 votes.[106]

Nader's reputation was hurt by this perception, which may have hindered his goals as an activist. For example, Mother Jones wrote about the so-called "rank-and-file liberals" who saw Nader negatively after the election and pointed out that Public Citizen, the organization Nader founded in 1971, suffered a drop in contributions. Mother Jones also cited a Public Citizen letter sent out to people interested in Nader's relation with the organization at that time, with the disclaimer: "Although Ralph Nader was our founder, he has not held an official position in the organization since 1980 and does not serve on the board. Public Citizen—and the other groups that Mr. Nader founded—act independently."[107]

Democratic party strategist and Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) chair Al From expressed a different view. In the January 24, 2001, issue[108] of the DLC's Blueprint magazine he wrote, "I think they're wrong on all counts. The assertion that Nader's marginal vote hurt Gore is not borne out by polling data. When exit pollers asked voters how they would have voted in a two-way race, Bush actually won by a point. That was better than he did with Nader in the race."[109]

In an online article published by Salon.com on Tuesday, November 28, 2000, Texan progressive activist Jim Hightower claimed that in Florida, a state Gore lost by only 537 votes, 24,000 Democrats voted for Nader, while another 308,000 Democrats voted for Bush. According to Hightower, 191,000 self-described liberals in Florida voted for Bush, while fewer than 34,000 voted for Nader.[110]

Press influence on race

In their 2007 book The Nightly News Nightmare: Network Television's Coverage of US Presidential Elections, 1988–2004, professors Stephen J. Farnsworth and S. Robert Lichter said that most media outlets influenced the outcome of the election through the use of horse race journalism.[111] Some liberal supporters of Al Gore argued that the media had a bias against Gore and in favor of Bush. Peter Hart and Jim Naureckas, two commentators for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), called the media "serial exaggerators" and took the view that several media outlets were constantly exaggerating criticism of Gore:[112] they further argued that the media falsely claimed Gore lied when he claimed he spoke in an overcrowded science class in Sarasota, Florida,[112] and that the media gave Bush a pass on certain issues, such as Bush allegedly exaggerating how much money he signed into the annual Texas state budget to help the uninsured during his second debate with Gore in October 2000.[112] In the April 2000 issue of Washington Monthly, columnist Robert Parry wrote that media outlets exaggerated Gore's supposed claim that he "discovered" the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York during a campaign speech in Concord, New Hampshire on November 30, 1999,[113] when he had only claimed he "found" it after it was already evacuated in 1978 because of chemical contamination.[113] Rolling Stone columnist Eric Boehlert also alleged media outlets exaggerated criticism of Gore as early as July 22, 1999,[114] when Gore, known for being an environmentalist, had a friend release 500 million gallons of water into a drought-stricken river to help keep his boat afloat for a photo shoot;[114] Boehlert claimed that media outlets exaggerated the actual number of gallons that were released, as they claimed it was 4 billion.[114]

Effects on future elections and Supreme Court

A number of subsequent articles have characterized the election in 2000, and the Supreme Court's decision in Bush v. Gore, as damaging the reputation of the Supreme Court, increasing the view of judges as partisan, and decreasing Americans' trust in the integrity of elections.[115][116][117][118][119][120] The number of lawsuits brought over election issues more than doubled following the 2000 election cycle, an increase Richard L. Hasen of UC Irvine School of Law attributes to the "Florida fiasco".[119]

See also

- 2000 United States gubernatorial elections

- 2000 United States House of Representatives elections

- 2000 United States Senate elections

- First inauguration of George W. Bush

- List of close election results

- Ralph Nader's presidential campaigns

Footnotes

- ^ Electors were elected to all 538 apportioned positions; however, an elector from the District of Columbia pledged to the Gore/Lieberman ticket abstained from casting a vote for president or vice president, bringing the total number of electoral votes cast to 537.

- ^ 267 electors pledged to the Gore/Lieberman ticket were elected; however, an elector from the District of Columbia abstained from casting a vote for president or vice president, bringing the ticket's total number of electoral votes to 266.

- ^ a b One faithless elector from Washington, D.C., Barbara Lett-Simmons, abstained from voting in protest of the District's lack of voting representation in the United States Congress. Washington, D.C. has a non-voting delegate to Congress. She had been expected to vote for Gore/Lieberman.[73]

References

- ^ "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- ^ Pruitt, Sarah. "7 Most Contentious U.S. Presidential Elections". HISTORY. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Haddad, Ken (November 7, 2016). "5 of the closest Presidential elections in US history". WDIV. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Fain, Thom. "5 of the closest presidential elections in U.S. history". fosters.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Wood, Richard (July 25, 2017). "Top 9 closest US presidential elections since 1945". Here Is The City. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Wolter, Kirk; Jergovic, Diana; Moore, Whitney; Murphy, Joe; O'Muircheartaigh, Colm (February 2003). "Statistical Practice: Reliability of the Uncertified Ballots in the 2000 Presidential Election in Florida" (PDF). The American Statistician. 57 (1). American Statistical Association: 1–14. doi:10.1198/0003130031144. JSTOR 3087271. S2CID 120778921. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d deHaven-Smith, Lance, ed. (2005). The Battle for Florida: An Annotated Compendium of Materials from the 2000 Presidential Election. Gainesville, Florida, United States: University Press of Florida. pp. 8, 16, 37–41.

- ^ "Federal Elections 2000: 2000 Presidential Electoral and Popular Vote Table". Federal Election Commission. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Frontline. Boston. October 12, 2004. PBS. WGBH-TV. The Choice.

- ^ "Iowa Caucuses". www.gwu.edu. George Washington University. January 24, 2000. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ "The 2000 Campaign; Crushed in Iowa, Hatch Abandons Campaign and Endorses Bush". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 27, 2000. p. 22. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 1, 2022. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Evan and Isikoff, Michael (March 5, 2000). "How McCain Does It". Newsweek. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Balz, Dan (February 2, 2000). "McCain Stuns Bush in N.H. Primary". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ Wayne, Leslie (February 10, 2000). "Forbes Spent Millions, but for Little Gain". The New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ Borger, Julian (February 20, 2000). "Bush win stuns McCain". The Guardian. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Interview with John McCain". Dadmag.com. June 4, 2000. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ Berke, Richard L. (February 23, 2000). "McCain Rebounds in Michigan, Buoyed by Big Crossover Vote, And Wins Easily in Home State". The New York Times. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ Holmes, Steven A. "After Campaigning on Candor, McCain Admits He Lacked It on Confederate Flag Issue Archived February 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. April 20, 2000. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ Broder, David S.; Allen, Mike (February 28, 2000). "Bush Cites Regret on Bob Jones". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ Timberg, Craig; Blum, Justin (February 29, 2000). "McCain Attacks Two Leaders of Christian Right". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "Why Virginia Loves George". CBS News. February 29, 2000. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "Cheney changes voter registration, boosts Bush running mate chances". Deseret News. July 22, 2000. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "West Memphis Kerrey bows out of 2000 presidential race". CNN. December 13, 1998. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ York, Anthony (September 2, 1999) "Life of the Party?" Archived October 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Salon News.

- ^ Dessauer, Carin (April 8, 1998). "Wellstone Launches Presidential Exploratory Committee". CNN. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ "Gore, Lieberman prepare for public debut of Democratic ticket". CNN. August 8, 2000. Archived from the original on November 5, 2008.

- ^ "Q&A with Socialist Party presidential candidate Brian Moore". Independent Weekly. October 8, 2008. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ The Buchanan/Foster ticket did not appear in Michigan and D.C.

- ^ "Green Party Presidential Ticket – President: Ralph Nader, Vice President: Winona LaDuke". Thegreenpapers.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Libertarian Party Presidential Ticket – President: Harry Browne, Vice President: Art Olivier". The Green Papers. July 3, 2000. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Libertarian Party Presidential Ticket". The Green Papers. July 2, 2000. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ a b "Bob Bickford "2000 Presidential Status Summary (table)" Ballot Access News June 29, 2000". October 1, 2000. Archived from the original on September 17, 2002. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Richard Winger""Natural Law Convention" Ballot Access News October 1, 2000, Volume 16, Number 7". Archived from the original on June 18, 2002. Retrieved June 18, 2002.

- ^ "The Second Gore-Bush Presidential Debate". 2000 Debate Transcript. Commission on Presidential Debates. 2004. Archived from the original on April 3, 2005. Retrieved October 21, 2005.

- ^ "Election 2000 Archive". CNN/AllPolitics.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ Rather, Dan (August 9, 2000). "Out of the Shadows". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009.

- ^ The New York Times. When a Kiss Isn't Just a Kiss Archived September 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. August 20, 2000.

- ^ "Gore's Defeat: Don't Blame Nader". Greens.org. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (November 8, 2000). "Why Gore (Probably) Lost". Slate. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "Nader assails major parties: scoffs at charge he drains liberal vote". CBS. Associated Press. April 6, 2000. Archived from the original on April 10, 2002. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

There is a difference between Tweedledum and Tweedledee, but not that much.

- ^ "CNN Transcript - CNN NewsStand: Presidential Race Intensifies; Gore Campaign Worried Ralph Nader Could Swing Election to Bush - October 26, 2000". Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "GOP Group To Air Pro-Nader TV Ads". Washingtonpost.com. October 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Baer, Susan (October 26, 2000). "Nader rejects concerns about role as spoiler". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "The 2000 Campaign: Campaign Briefing Published". The New York Times. September 5, 2000. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "CPD: 2000 Debates". www.debates.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ a b "Open Debates | What Happened in 2000?". opendebates.org. 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (October 5, 2000). "The 2000 Campaign: the Green Party; Nader Wants Apology From Debate Panel for Turning Him Away". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Nader, Ralph (2002). "Crashing the Party". naderlibrary.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Winger, Richard (2002). "Ballot Access News – May 1, 2002". Archived from the original on June 4, 2003. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Safire, William (2008). Safire's political dictionary. Oxford University Press. pp. 270–71. ISBN 9780195343342. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ Krugman, Paul R.; Bush, George Walker (2001). Fuzzy math: the essential guide to the Bush tax plan. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393050622.

fuzzy math.

- ^ Barstow, David; Van Natta, Don Jr. (July 15, 2001). "Examining the Vote; How Bush Took Florida: Mining the Overseas Absentee Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ "SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. No. 00-949 (00A504) Bush v. Gore, On Application For Stay" (PDF). December 9, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ "Florida legislature to appoint electors during special session Friday". The St. Augustine Record. December 7, 2000. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ "FLORIDA LEGISLATURE–SPECIAL SESSION A–2000 (Dec) HISTORY OF HOUSE BILLS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Electoral College Frequently Asked Questions". archives.gov. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ^ "2000 Presidential General Election Results". fec.gov. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ "Who is boycotting the Trump inauguration?". BBC News. January 20, 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections - Compare Data". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Leinsdorf, Joshua (November 4, 2000). "American Voters Pull Together To Make Tough Choices". Institute of Election Analysis. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Ramsey, Ross (November 6, 2000). "Excess Stomach Acid". The Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Anything Can Happen". CBS News. November 2, 2000. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Devlin, Ron (November 7, 2000). "Old buttons pin down history of the presidency". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "War on the Electoral College". Slate. November 7, 2000. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Brownfield, Tony (November 3, 2020). "The Five Closest Presidential Elections". Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "The 2016 Streak Breakers". Sabato Crystal Ball. October 6, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2017.