Contents

Ancient Pistol is a swaggering soldier who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare. Although full of grandiose boasts about his prowess, he is essentially a coward. The character is introduced in Henry IV, Part 2, and he reappears in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry V.

The character's first name is never given. He is referred to as Falstaff's "ancient", meaning "ensign", or standard bearer.

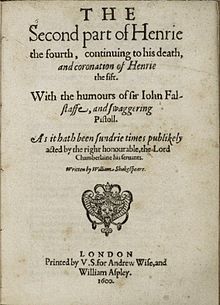

Henry IV, Part 2

Pistol is introduced as a "swaggerer" who suddenly turns up at the Boar's Head Tavern, contrary to the wishes of the hostess, Mistress Quickly. Falstaff tells her that Pistol is his "ancient" (ensign). He gets into a fight with Falstaff after an exchange of insults with the prostitute Doll Tearsheet, who calls him "the foul-mouth'dst rogue in England".

Later, when Falstaff stops off at Justice Shallow's house after the defeat of Scrope, Pistol appears bringing news of the death of Henry IV, asserting that Falstaff is "now one of the greatest men in this realm". In another scene it is revealed that the police are after him because a man he assaulted in tandem with Doll Tearsheet and Mistress Quickly has died. He shares Falstaff's punishment of banishment from the king at the end of the play.

The Merry Wives of Windsor

Pistol reappears as Falstaff's crony in The Merry Wives of Windsor and is roped into Falstaff's scheme to seduce the wives. He and his colleague Corporal Nym believe such a scheme beneath their dignity as soldiers, and refuse to participate. Falstaff dismisses them from his service and in revenge they inform the wives' husbands of Falstaff's plan, leading to Falstaff's humiliations at their hands. He also decides to pursue Mistress Quickly. Dressed as a fairy, he participates in the final scene at Herne's Oak.

The phrase "the world's my oyster" derives from one of Pistol's lines in the play, "Why then the world's mine oyster, which I with sword will open."

Henry V

Pistol plays a major role in Henry V. He marries Mistress Quickly after the death of Falstaff, though it is also implied that he is still involved with Doll Tearsheet. In the war in France, he gets into a feud with the Welsh officer Fluellen, when Fluellen refuses to pardon Pistol's friend Bardolph who has been caught looting. In the end Fluellen beats him and forces him to eat a raw leek. At Agincourt he becomes involved in comic antics with a French soldier. After the battle he gets a letter from which he learns that "my Doll is dead" from "malady of France", i.e. from syphilis. (It is unclear whether this refers to Doll Tearsheet, or to Mistress Quickly.)[1] He says he intends to desert, return to England and become a pimp and a thief.

Character role

Pistol's character may have been derived from the boastful soldier figure Il Capitano, a stock figure in commedia del arte, which also has precedents in Roman comedies, in the Miles Gloriosus figure, such as Thraso in Terence's Eunuchus. Pistol is the "Elizabethan version of the miles gloriosus, the braggart soldier from Roman-comedy".[2] Another possible source is the character Piston in Thomas Kyd's play Soliman and Perseda.[3] There are numerous puns on his name in the plays, with comic reference to his explosive temperament, tendency to misfire, and his unrestrained phallic sexuality ("discharge upon mine hostess").[4]

His bombastic speeches may also be parodies of the self-dramatising heroes of Christopher Marlowe's plays.[3] In his first scene, he misquotes one of Tamburlaine's lines from Marlowe's Tamburlaine the Great. He has an "irresistible impulse to form horrendous speeches out of half-remembered tags from old plays written in 'Cambyses vein.'"[5] Pistol's florid bombast is often contrasted with the gnomic pronouncements of his colleague Corporal Nym.[3]

In Henry V, he essentially replicates Falstaff's role in the Henry IV plays, being the butt of jokes for his empty bluster while also parodying the rhetoric of the "noble" characters. However, he totally lacked his superior officer's wit and charm. His role may have been expanded because Falstaff had been killed off.[5] His antics with the French soldier are derived from those of the equivalent character (Derick) in Shakespeare's source, The Famous Victories of Henry V.[6]

References in other works

Pistol appears in William Kenrick's play Falstaff's Wedding (1766 version), in which he escapes arrest by disguising himself as a Spanish swordsman called Antico del Pistolo, and impresses Justice Shallow. He competes with Falstaff for the hand of Mistress Ursula, but gets tricked by Shallow into marrying Mistress Quickly.[7]

James White's book Falstaff's Letters (1796) purports to be a collection of letters written by Falstaff and his cronies, provided by a descendant of Mistress Quickly's sister. Several letters purport to have been written by Pistol in his characteristic florid style.[8]

In film and television

- On film, in the acclaimed 1944 Laurence Olivier version of Henry V, Pistol was played by Robert Newton.

- In the 1964 film Falstaff, aka Chimes at Midnight, Orson Welles's take on Henry IV with parts from Henry V and The Merry Wives of Windsor, Pistol was played by Michael Aldridge.

- in the 1989 Kenneth Branagh version of Henry V, he was played by Robert Stephens.

- Three soldier characters in the film Cold Mountain are named Bardolph, Nym, and Pistol.

- In the acclaimed television series An Age of Kings, presenting Shakespeare's history-plays from Richard II to Richard III, in the Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V episodes, Pistol is played by George A. Cooper.

- In the 1979 BBC production of Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V that was part of their series of presentations of Shakespeare's plays, Pistol was played by Bryan Pringle, and in The Merry Wives of Windsor that was part of the 1982 season, by Nigel Terry.

- In the 1989 presentation of the Henriad, filmed live on stage, that was part of Michael Bogdanov/Michael Pennington's English Shakespeare Company's War of the Roses series, Pistol was played by Paul Brennan.

- In the 2012 television series The Hollow Crown, Pistol was played in Henry IV, Part 2 and Henry V by Paul Ritter.

References

- ^ Dr. Andrew Griffin, Locating the Queen's Men, 1583–1603, Ashgate, 2013, p.142

- ^ Victor L. Cahn, Shakespeare the Playwright: A Companion to the Complete Tragedies, Histories, Comedies, and Romances, Praeger, Westport, 1996. p.468

- ^ a b c Oscar James Campbell, Shakespeare's Satire: Oxford University Press, London, 1943, p.72

- ^ Stanley Wells, Eric Partridge, Shakespeare's Bawdy, Routledge, London, 2001. p.208-9.

- ^ a b J. Madison Davis, The Shakespeare Name and Place Dictionary, Routledge, 2012, p.387.

- ^ Greer, Clayton A. "Shakespeare's Use of The Famous Victories of Henry V," Notes & Queries. n. s. 1 (June 1954): 238–41

- ^ Kendrick, W., Falstaff's Wedding, A Comedy: as it is acted at the theatre Royal in Drury-Lane. Being a sequel to the Second Part of the play of King Henry the Fourth. Written in imitation of Shakespeare. In magnis voluisse sat est. London. Printed for L. Davis and C. Reyers, in Holborn; and J. Ayan, in Pater-noster-Row. 1766.

- ^ White, James, Falsteff's Letters, London, Robson, 1877, p.39.