Contents

The City Investing Building, also known as the Broadway–Cortlandt Building and the Benenson Building, was an office building and early skyscraper in Manhattan, New York. Serving as the headquarters of the City Investing Company, it was on Cortlandt Street between Church Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. The building was designed by Francis Kimball and constructed by the Hedden Construction Company.

Because of the area's sloping topography, the City Investing Building rose 32 stories above Broadway and 33 stories above Church Street, excluding an attic. The bulk of the building was 26 stories high above Church Street and was capped by a seven-story central portion with gable roofs. The building had an asymmetrical F-shaped footprint with a light court facing Cortlandt Street, as well as a wing to Broadway that wrapped around a real estate holdout, the Gilsey Building. Inside was a massive lobby stretching between Broadway and Church Street. The upper stories each contained between 5,200 and 19,500 square feet (480 and 1,810 m2) of space on each floor.

Work on the City Investing Building started in 1906, and it opened in 1908 with about 12 acres (49,000 m2; 520,000 sq ft) of floor area, becoming one of New York City's largest office buildings at the time. Though developed by the City Investing Company, the structure had multiple owners throughout its existence. The City Investing Building was sold to the financier Grigori Benenson (1860–1939) in 1919 and renamed the Benenson Building. After Benenson was unable to pay the mortgage, it was sold twice in the 1930s. The building was renamed 165 Broadway by 1938 and was renovated in 1941. The City Investing Building and the adjacent Singer Building were razed in 1968 to make room for One Liberty Plaza, which had more than twice the floor area than the two former buildings combined.

Site

The City Investing Building was in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, with frontage on Church Street to the west,[a] Cortlandt Street to the north, and Broadway to the east. The City Investing Building had a frontage of 209 feet (64 m) on Cortlandt Street, 109 feet (33 m) on Church Street and Trinity Place, and 37.5 feet (11.4 m) on Broadway.[6][5][3] It had a depth of 313 feet (95 m), abutting the Singer Building to the south.[6] The site slopes down from Broadway to Church Street, so that there was a raised basement facing Church Street, which was below ground at Broadway.[7]

The City Investing Building's northeastern section wrapped around a real estate holdout, the Gilsey Building (also the Wessels Building or Benedict Building), at the southwestern corner of Cortlandt Street and Broadway.[6][8] The Gilsey Building had a frontage of 56.5 feet (17.2 m) on Broadway and 106 feet (32 m) on Cortlandt Street.[3] The City Investing Building's original owner, the City Investing Company, held a long-term lease for the Gilsey Building, which would have eventually been demolished to make way for an addition to the City Investing Building.[9][10] To the south, there was a gap of 10 feet (3.0 m) between the City Investing Building and the Singer Tower addition to the Singer Building, which was built nearly simultaneously with the City Investing Building. The narrowness of the gap was a result of a design choice by the Singer's architect, Ernest Flagg. The columns required to support the Singer Tower would have been too large to place atop the original Singer Building, at the south end of the same block near Liberty Street.[11]

Architecture

The City Investing Building was designed by Francis H. Kimball.[12][13][14] The general contract was awarded to the Hedden Construction Company and the contract for the foundation work was given to the O'Rourke Engineering and Contracting Company. In addition, Weiskopf and Stern were consultants for the steel frame, Griggs and Holbrook were consultants for steam and electricity, and William C. Tucker was consulting sanitary engineer.[14][15] The steel was made by the American Bridge Company and erected by Post and McCord. The stonework came from William Bradley & Sons; the ornamental ironwork from Hecla Iron Works; the terracotta and other tilework from the National Fireproofing Company; the plumbing from Wells and Newton; and the marble work from J. H. Shipway and Bros.[15]

The City Investing Building's facade was divided into three horizontal sections: a base with four stories and a raised basement; a shaft with 21 stories and a full-height cornice; and a capital with six stories and an attic. There was also a cellar below the raised basement.[16][17] The City Investing Building rose 486 feet (148 m) above Broadway.[8][15] Sources differ on how many stories the building had. An official building brochure and the Engineering Record described the building as having 32 stories, as counted from Broadway, although this excluded the attic.[8][17] The Real Estate Record and Guide described the building as rising 33 stories, as counted from Church Street, but excluding the attic.[18] Yet another source gave the height as 480 feet (150 m) with 34 stories, including the attic.[19]

Form

The City Investing Building was largely shaped in an "F", with the two northward "prongs" of the "F" flanking a 40-by-65-foot (12 by 20 m) light court on Cortlandt Street. The light court rose above the second story on the Cortlandt Street elevation. A wing ran eastward to Broadway, between the Gilsey and Singer buildings.[6][3] The bulk of the building, comprising the base and shaft, consisted of 25 occupiable stories above Broadway, plus a 26th story in the cornice.[15] The "prongs" on Cortlandt Street were designed as narrow towers terminating at the 26th story. Above the Broadway wing, the 26th story was topped by a series of engaged columns with a belvedere at the center. A flat roof rose above much of the 26th story.[3] The central section of the building, recessed from the light court on Cortlandt Street, rose six additional stories into the capital, with an ornate gable roof made of copper. A smaller gable rose to the 31st floor directly to the east.[3]

Facade

The five-story base was clad with light stone, while the shaft and capital were decorated with white brick and terracotta.[3][10][4] Porcelain and enamel brick were used to reduce cleaning costs, since that type of brick did not discolor over time.[20]

The main entrance was at Broadway and contained a semicircular-headed opening. The fourth floor was topped by a large cornice that was at the same level as the roof of the six-story Gilsey Building.[3] Robert E. Dowling, the building's developer, hired Vincenzo Alfano to design sculptural groups for the facade.[21]

The 5th through 25th floors contained window bays, which generally contained two or three windows on each story. The corner bays on the "prongs" facing Cortlandt Street contained one window per floor. At various points on the facade, some of the center bays on each side contained groupings of several stories, each of which contained engaged columns and balconies. There were also horizontal belt courses between several stories. The 26th floor was inside the cornice.[3]

Structural features

The City Investing Building used a steel frame with concrete-slab floors, terracotta floor arches and partitions, and interior marble work. When completed, the building was said to weigh 86,000 short tons (77,000 long tons), excluding live loads.[8][4] The steel frame alone weighed 12,000 short tons (11,000 long tons; 11,000 t).[8][15] As completed, the building used 9.1 million bricks, 25,000 lighting fixtures, 3,000 short tons (2,700 long tons; 2,700 t) of terracotta, about 2,600,000 square feet (240,000 m2) of plaster, about 1,870,000 square feet (174,000 m2) of hollow tile, 8,170,000 pounds (3,710,000 kg) of marble, and about 21.8 million mosaic cubes. Also included in the building was many miles of plumbing, steam piping, wood base, picture molding, conduits, and electrical wiring.[22][23] The building contained woodwork made of fireproofed mahogany.[12]

Superstructure

The superstructure consisted of a steel cage wherein the columns at every story supported the walls. The columns, in turn, sat on cast-steel pedestals, which transmitted their loads through girders and grillages. There were 89 columns on each floor, arranged in six rows. The largest column carried a load of 1,719 short tons (1,535 long tons; 1,559 t) and had a cross section of 253.9 square inches (1,638 cm2).[3] The floors consisted of hollow-tile flat arches or concrete with cinder filling, and were surfaced with mosaic or terrazzo tiles.[24] The distributing girders on the third story of the Broadway wing were the largest and heaviest to be used in the building; they comprised a triple girder weighing about 105 short tons (94 long tons; 95 t) and spanning the entire 37-foot (11 m) width of that wing.[25] Portal braces and curved knee braces were included to provide wind resistance, but also contributed to the building's weight.[16]

The exterior walls were curtain walls whose thicknesses had been prescribed by city building codes of the time. The south wall was generally 32 inches (810 mm) thick at the base, tapering to 12 feet (3.7 m) just below the 25th floor. The other walls varied in thickness from 32 inches at the base to 20 inches (510 mm) below the 25th floor. There were also two walls carried atop the third-floor girders, which extended to the 27th and 32nd floors.[26]

Foundation

The foundation was excavated using rectangular caissons of varying width.[27] The pits were drilled through layers of earth, quicksand, clay, gravel, and water to a solid rock layer 80 feet (24 m) beneath Broadway.[8] The main excavation was carried to 24 feet (7.3 m) below Broadway, except at the site of the boiler room, where the excavations were carried 30 feet (9.1 m) deep.[7] Each caisson was 12.33 feet (4 m) and made of yellow pine. A steel shaft rose from each of the caissons. The underlying ground was drawn out from the caissons, and then the caissons were filled with concrete.[28] The retaining walls of the foundation were then constructed of concrete slabs between I-beams spaced 5 feet (1.5 m) apart.[26] The excavation involved removing 4,500 cubic yards (3,400 m3) of masonry and 11,000 cubic yards (8,400 m3) of earth, while the foundation piers used 11,000 cubic yards (8,400 m3) of concrete. Sections of the masonry basement floors from the previous buildings on the site were also removed in the process.[29]

Within the foundation were placed 59 concrete piers, which carried the columns of the aboveground superstructure. The cross-sections of the piers varied, with the smallest measuring 6 by 6 feet (1.8 by 1.8 m), and the largest measuring 8.5 by 37.33 feet (2.6 by 11.4 m).[8] The caissons supported foundation piers that were topped by plates with grillages of transversely laid I-beams. Most of the superstructure's exterior columns were supported on cantilevers; deep plate girders were placed over the grillages, and the cantilevers extended outward from these girders, where they supported the columns.[26] The foundation also used distributing girders, some of which were triple girders weighing 90 short tons (80 long tons; 82 t).[3] The cellar floor was poured as a single layer of concrete, 6 feet (1.8 m) thick. This helped distribute the building loads and counteracted the upward hydrostatic pressure.[8][16]

Interior

Interior spaces

The City Investing Building was one of New York City's largest office buildings at the time of its completion,[30] with an estimated 12 acres (49,000 m2; 520,000 sq ft) of floor area.[18][23] Generally, there was more space on higher stories than on lower stories, largely because the building's elevators were staggered into three banks serving different sets of floors.[10][31] The 5th through 9th floors typically had 17,600 square feet (1,640 m2) per floor; the 10th through 17th floors each had 18,500 square feet (1,720 m2); and the 18th through 25th floors each had 19,500 square feet (1,810 m2). However, the 27th through 31st floors, located in the smaller "capital" of the building, typically had 5,200 square feet (480 m2).[31] On the top of the building was a luncheon club.[32]

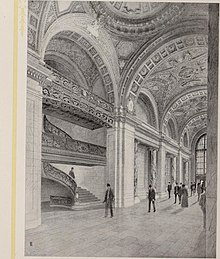

The entrance arch on Broadway led to a limestone vestibule about 30 feet (9.1 m) deep, which contained the main doors.[4] Inside the vestibule was a double-height lobby running westward to the elevated Cortlandt Street station of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company's Sixth Avenue Line at Church Street.[12] It measured 40 feet (12 m) tall and 32 feet (9.8 m) wide.[3][10][18] The arched ceiling of the lobby was decorated with colorful frescoes.[18] The lobby was clad throughout with several types of Italian marbles. Three elevator banks extended from the southern wall of the lobby. The second floor contained offices north of the lobby, and a footbridge was placed across the lobby to connect the elevators and offices.[10]

The upper floors typically had a west–east elevator hallway along the southern wall, with the other areas being used for rental space.[31] Generally, the ceiling heights of the lower stories were higher than on the upper stories. The first story had a ceiling of 22 feet (6.7 m), the second story 20 feet (6.1 m) and the third story 16.5 feet (5.0 m). Most of the subsequent stories had ceiling heights of between 11 and 14 feet (3.4 and 4.3 m), although the 26th floor had a ceiling of 16 feet (4.9 m). The basement, at ground level at Church Street, had a ceiling of 13 feet (4.0 m) and the cellar had a ceiling of 24 feet (7.3 m).[17]

Utilities and elevators

A 32,000-square-foot (3,000 m2) cellar extended under the Broadway sidewalk, and contained the building's boiler room.[3] The boiler plant was capable of an output of 2,000 horsepower (1,500 kW).[26] The building also had a water system that could filter 864,000 U.S. gallons (3,270,000 L; 719,000 imp gal) per day and its plumbing system could pump out five times as much.[18][23] There were two water tanks: one had a capacity of 12,500 U.S. gallons (47,000 L; 10,400 imp gal) and was used for fire protection, while the other had a capacity of 9,000 U.S. gallons (34,000 L; 7,500 imp gal) and served the clients.[26] Also in the building was an electric light plant.[12]

The building contained 24 elevators in total. From the lobby, there were 21 plunger elevators for passengers and 2 electric elevators for freight.[12][15] The plunger elevators were made by the Standard Plunger Company and the electric elevators were made by Otis Elevator.[15] The elevators were placed in three banks the south side of the building, along the section facing the Singer Tower.[30][33] Seven elevators served all the floors from the lobby to the 9th story; another seven ran express from the lobby to the 9th story, then served all floors through the 17th; and the final seven ran express from the lobby to the 17th story, then served all floors to the 26th.[18][26][33][b] A separate elevator served the 25th through 32nd stories.[18][26] Two staircases ran between the basement and 25th floor, with another staircase running to the 32nd floor.[34]

History

The City Investing Building was developed by Robert E. Dowling, who in the first decade of the 20th century was also developing the Trinity and United States Realty Buildings nearby.[30][35] Dowling was the president of the City Investing Company, a conglomerate that had split from the United States Realty and Construction Company in late 1904.[35] By early 1906, he had hired Kimball,[36] who at the time was well known for constructing other bulky skyscrapers whose construction required pneumatic caissons.[13] Dowling intended the building to include large floors for the growing number of tenants who sought large amounts of office space on a single floor.[37][38] Dowling also wanted a building with a grand lobby and 21 tenant elevators.[4][10]

Construction

The City Investing Company bought the Coal and Iron Exchange Building[c] at Church and Cortlandt Streets in January 1906.[40] It bought further land on Cortlandt Street the same April.[41] The general construction contract was given to the Hedden Construction Company in September 1906.[42] The next month, there circulated rumors that the City Investing Building would rise to 39 stories—one less than the Singer Tower to the south, which was simultaneously being erected as the world's tallest building—but this modification did not happen.[43] Demolition of buildings on the City Investing Building's site proceeded through 1906. The Coal and Iron Exchange Building took five months to destroy, because of the extremely thick materials it used; it was demolished by October 1906,[44] although its cornerstone was not retrieved until June 1907.[45]

Excavation of the foundations began in November 1906, with an average of 275 workers during the day shift and 100 workers during the night shift.[46] The excavation was required to be completed in 120 days. To remove the spoils from the foundation, three temporary wooden platforms were constructed to street level. Hoisting engines were installed to place the beams for the foundation, while the piers were sunk into the ground under their own weight.[7][16] Because of the lack of space in the area, the contractors' offices were housed beneath the temporary platforms.[27] During the process of excavation, the Gilsey Building's foundations were underpinned or shored up, because that building had relatively shallow foundations descending only 18 feet (5.5 m) below Broadway.[29]

After the foundations were completed, a light wooden falsework was erected on the Broadway wing to support the traveler, which contained two derricks to erect the massive girders in that section.[25] The traveler was moved deeper into the lot as the girders were erected. The girders were erected quickly at night, with 16 girders and 20 columns being erected in a week.[47] A worker was killed during construction when a temporary floor collapsed in June 1907.[48][49] The building was completed in a then-record 22 months, having employed 3,000 workers.[16]

Use

Tenants started moving into the building in April 1908.[50][51] Early tenants of the City Investing Building included the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, Midvale Steel, the American Car and Foundry Company, the Southern Pacific Transportation Company, the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, New York Air Brake, and the Jones and Laughlin Steel Company.[12] In December 1919, London banker Grigori Benenson bought the City Investing Building for $10 million in cash. At the time, the building was estimated to be worth $7 million, but contained a $5.75 million mortgage held by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.[5][12] The City Investing Building was accordingly renamed the Benenson Building.[15] Benenson acquired the title to the building in July 1920.[52] He received a $9.5 million mortgage loan for the building in 1926.[53]

During the 1920s, the Benenson Building gained tenants such as the Chemical Bank[54] and advertising agency Albert Frank & Company.[55] Benenson also brought adjacent property to the north, intending to construct a supertall skyscraper on the site, but these plans were canceled due to the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[56] Benenson's company suffered financially from the Wall Street Crash and defaulted on its mortgages in the years afterward.[57] The Benenson Building and the company's other structures, including the adjacent 99 Liberty Street, were placed for sale in October 1931 as part of foreclosure proceedings against the company. The building at the time was assessed as being worth $10.4 million.[58] Charles F. Noyes acquired the Benenson Building and several of Benenson's other properties the next month.[59]

By 1936, there were plans to renovate the Benenson Building, with the project being funded through rental income.[60] The Benenson Building and another adjacent structure were auctioned again in 1938 to satisfy the liens against the properties.[61][62] The New York Trust Company acquired the Benenson Building for $5 million, and the building was renamed 165 Broadway.[63] The building was renovated in 1941 for $300,000. The entrances, elevators, and corridors were renovated, and new fluorescent lighting was installed. At the time, the Chemical Bank occupied the first six floors of both 165 Broadway and the Gilsey Building.[64][65] 165 Broadway, the Gilsey Building, and 99 Liberty Street were sold in 1947 to N. K. Winston and George Gregory for $11 million.[66]

Demolition

In 1964, United States Steel acquired the City Investing Building, along with the neighboring Singer Building.[67] U.S. Steel planned to demolish the entire block to erect a new 54-story headquarters on the same site.[68] Although preservationists attempted to get the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission to protect the Singer Building,[69] the City Investing Building received relatively little notice.[30] Demolition of both buildings was underway by 1968.[70]

The U.S. Steel Building (later known as One Liberty Plaza) was built on the site, being completed in 1973.[71] One Liberty Plaza had at least twice the two former buildings' combined interior area.[30] One Liberty Plaza contained 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2) per floor,[72] compared with the 5,200 to 19,500 square feet (480 to 1,810 m2) per floor in the City Investing Building.[31] At the time of its destruction, the City Investing Building was the third-tallest building ever demolished, behind the Morrison Hotel and the Singer Building.[73][74]

Impact

The City Investing Building, along with other nearby sites such as the Singer Building, Hudson Terminal, and the Equitable Building, was a frequently photographed skyscraper in Lower Manhattan. The completion of the Equitable Building to the southeast in 1915 placed the City Investing Building into permanent shadow up to the 24th floor.[75] The situation led to New York City's 1916 Zoning Resolution, which required buildings to be set back above a certain height.[76]

According to architectural journalist Christopher Gray and architectural historians Sarah Landau and Carl Condit, the City Investing Building was regarded as a "monument to greed" with its sheer size.[6][30] Photographs of the building almost always showed its northern side on Cortlandt Street because its primary elevation to the east along Broadway was excessively narrow.[19] Architect Donn Barber described the facade as "somewhat showy both in design and material" and regarded the lobby as "the finest piece of commercial designing and execution that we have yet seen downtown."[16] Kimball, the building's architect, characterized the light-toned exterior as contrasting with the "darker and more somber" appearance of nearby buildings.[10][77]

References

Notes

- ^ Church Street forms a continuous street with Trinity Place, which continues southward at Liberty Street, one block south of the City Investing Building's former site.[2] Some sources refer to the section of the street outside the City Investing Building's site as Trinity Place,[3] while others refer to it as Church Street.[4][5]

- ^ The bank of elevators running to the 9th story was arranged in an arc between the two banks of express elevators, which were arranged in a straight line. The bank of elevators running to the 17th story was on the western section of the building's southern wall, while the bank of elevators to the 26th story was on the eastern section of the same wall.[33]

- ^ Also known as the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company building[39]

Citations

- ^ "Emporis building ID 102530". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Engineering Record 1906, p. 566.

- ^ a b c d e Landau & Condit 1996, p. 325.

- ^ a b c "City Investing Building Sold to a Russian". New York Herald. December 19, 1919. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Landau & Condit 1996, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Engineering Record 1907, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Engineering Record 1907, p. 267.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 324–325.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kimball, Francis H. (May 1908). "City Investing Building". The New York Architect. Vol. 2, no. 5. Harwell-Evans Company. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (March 29, 2012). "The Hemming In of the Singer Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "165 Broadway Sold to London Banker; City Investing Building, Assessed at $7,000,000, Bought by Grigori Benenson". The New York Times. December 19, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, p. 324.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1906, p. 568.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landau & Condit 1996, p. 437.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Broadway–Cortlandt Company 1907, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Real Estate Record 1908, p. 38.

- ^ a b Gabrielan, Randall (2007). Along Broadway. Postcard History Series. Arcadia Pub. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7385-5031-2. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Building Material and Equipment" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 86, no. 2215. August 27, 1910. pp. 346–347. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "'Tip The Horn Up': Mr. Dowling Didn't Like to See His Money Falling Into Street". New-York Tribune. July 4, 1907. p. 12. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Real Estate Record 1908, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c "Buildings as Big as a Town". New York Sun. June 28, 1908. p. 22. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Engineering Record 1906, pp. 566–567.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, p. 696.

- ^ a b c d e f g Engineering Record 1906, p. 567.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, p. 269.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, pp. 269–270.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, pp. 267–268.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Christopher (August 29, 2013). "Twins, Except Architecturally". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Broadway–Cortlandt Company 1907, pp. 18, 20, 22, 24.

- ^ "For a New Luncheon Club.; It Will Occupy the 25th Floor of the City Investing Building". The New York Times. February 28, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Broadway–Cortlandt Company 1907, p. 16.

- ^ Real Estate Record 1908, p. 39.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 323–324.

- ^ "Prospective Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 77, no. 1980. February 24, 1906. p. 641. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Thirty-Story City Investing Building". The New York Times. March 25, 1906. p. 19. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Real Estate Record 1908, p. 17.

- ^ King, Moses (1893). Kings Handbook of New York City. King's Handbook of New York City: An Outline History and Description of the American Metropolis ; with Over One Thousand Illustrations. Moses King. p. 130. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "City Investing Co. Buys Coal and Iron Exchange; Ranks With Big Insurance Companies in Downtown Holdings. D. And H. To Move to Albany the Investing Company Will Not Replace Its Block Square Building With a Skyscraper at Present". The New York Times. January 13, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; City Investing Company Buys on Cortlandt Street – East Side Residences in Demand – Dealings by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. April 5, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Hedden Construction Co, Will Build the Broadway–Cortlandt". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 78, no. 2008. September 8, 1906. p. 448. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Broadway–Cortlandt May Go as High as the New Singer". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 78, no. 2014. October 20, 1906. p. 641. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Building Wreckers Thwarted for Months". The New York Times. October 7, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Prophecies in Box: Contents of Cornerstone of Coal and Iron, Building Revealed". New-York Tribune. June 27, 1907. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, p. 270.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, p. 697.

- ^ "One Killed; Three Hurt: Temporary Floor in Broadway–Cortlandt Building Collapses". New-York Tribune. June 13, 1907. p. 3. ProQuest 572013533. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Four Men Buried in Cement; 1 Dead". The New York Times. June 13, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "New York Air Brake.: President Starbuck Says Company Has Received a Number of New Orders the Last Ten Days". Wall Street Journal. April 22, 1908. p. 2. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 129140928. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Brief and Personal". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 81, no. 2098. May 30, 1908. p. 1015. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Title to 195 Broadway; J. Benenson is New Owner of the City Investing Building". The New York Times. July 2, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "$9,500,000 Loan for 165 Broadway". The New York Times. August 19, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Chemical National's Move; Bank to Be at 165 Broadway After New Building is Erected". The New York Times. December 22, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Albert Frank & Co. Move.; Advertising Agency to Open Offices at 165 Broadway Today". The New York Times. June 3, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Grigori Benenson, Noted Financier". The New York Times. April 6, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Benenson Terminal Faces Foreclosure; Manufacturers' Trust Co., as Trustee of $2,451,000 Notes, Files Against Properties". The New York Times. June 25, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Benenson Holdings Going at Auction; Downtown Properties Valued at More Than $28,000,000 in Foreclosure Sale". The New York Times. October 18, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "$23,775,779 Paid in Benenson Sale; Lower Manhattan Holdings Go to C.f. Noyes as Bidder in Record Foreclosure Auction". The New York Times. November 13, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 17, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Plan Modernization for Downtown Unit: Cooperation Sought From Bond. Holders of 26-story Offices at 165 Broadway". The New York Times. February 6, 1936. p. 38. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 101977077. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "165 Broadway to Be Sold; Auction of Benenson Building to Take Place Today". The New York Times. December 30, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Former Benenson Building Will Be Auctioned Today". New York Herald Tribune. December 30, 1938. p. 30. ProQuest 1247808218. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Mortgage Relief for Broadway Site". The New York Times. June 22, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "City Investing Building Put in Good Condition: $300,000 Renovation Job Brings Entrances, Halls and Fixtures Up to Date". New York Herald Tribune. March 23, 1941. p. C2. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Alterations Made at 165 Broadway: Modernization Work Ends in 31-story Edifice Under $300,000 Program". The New York Times. March 23, 1941. p. RE2. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 105510636. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "3 Buildings Sold in Wall St. Area: 165 Broadway and Adjoining Offices Figure in Deal Involving $11,000,000". The New York Times. December 25, 1947. p. 40. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 108001036. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Siteon Broadway Goes to U.S. Steel; Webb & Knapp Sells 2 Blocks Stock Exchange Spurned". The New York Times. March 19, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Fried, Joseph P. (April 5, 1968). "U.S. Steel to Erect a 54-Story Skyscraper Here; Lower Broadway Project Is Hailed by City as 'Great Planning Achievement'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Fried, Joseph P. (August 22, 1967). "Landmark on Lower Broadway to Go; End Near for Singer Building, A Forerunner of Skyscrapers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Vartan, Vartanig G. (February 15, 1968). "New Home Sought For Merrill Lynch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 361.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (January 2, 2005). "Once the Tallest Building, but Since 1967 a Ghost". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (May 14, 2018). "NYC is home to 23 of the world's tallest intentionally demolished buildings". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "The 10 Tallest Buildings Ever Demolished". ArchDaily. July 3, 2014. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Shadows Cast by Skyscrapers". Buildings and Building Management. Building Manager Publishing Company. November 1918. p. 38. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (July 25, 2016). "Zoning Arrived 100 Years Ago. It Changed New York City Forever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 11, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 325–326.

Sources

- "City Investing Building, Broadway–Cortlandt and Church streets". Broadway–Cortlandt Company. 1907 – via Internet Archive.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "Some Structural Features of the City Investing Company's Building, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 54, no. 21. November 24, 1906. pp. 566–567.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "The Largest Buildings of the Year" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 81, no. 2077. January 4, 1908. pp. 38–39 – via columbia.edu.

- "Volume 57". Engineering Record. Vol. 57. 1907.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Erection of the City Investing Company's Building". Engineering Record. Vol. 57, no. 24. June 15, 1907. pp. 696–697.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "The Pneumatic Foundations of the City Investing Building, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 57, no. 9. March 2, 1907. pp. 267–270.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Erection of the City Investing Company's Building". Engineering Record. Vol. 57, no. 24. June 15, 1907. pp. 696–697.