Contents

The Emirate of Abu Dhabi (/ˌæbuː ˈdɑːbi/, Arabic: إِمَارَة أَبُوظَبِي, romanized: Imārat Abū Ẓabī, pronounced [ʔabuː ˈðˤɑbi])[3] is one of seven emirates that constitute the United Arab Emirates. It is the largest emirate, accounting for 87% of the nation's total land area or 67,340 km2 (26,000 sq mi).[4]

Abu Dhabi also has the second-largest population of the seven emirates. In mid-2016, the emirate had a population of 2,908,000, with 551,500 being Emirati citizens, accounting for around 19% of the population.[5] The city of Abu Dhabi, after which the emirate is named, is the capital of both the emirate and the federation.[6]

In the early 1970s, two important developments influenced the status of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. The first was the establishment of the United Arab Emirates in December 1971, with Abu Dhabi as its initially temporary political and administrative capital. The second was the sharp increase in oil prices following the Yom Kippur War, which accompanied a change in the relationship between the oil exporting countries in the Middle East and foreign oil companies, leading to a dramatic rise in oil revenues.[7] See the 1973 oil crisis.

In 2023, Abu Dhabi had a nominal GDP of AED 1.02 trillion (US$277.9 billion), a nominal GDP per capita of US$84,900, and a government debt to GDP ratio of 16%.[2] In 2022, the size of oil and mining trade increased by 54% and accounted for 48% of GDP. Construction was the next largest contributor at 7.9%, followed by the financial sector at 6.1%.[8]

In recent times, the Emirate of Abu Dhabi has continuously contributed around 60% of the GDP of the United Arab Emirates, while its population constitutes only 34% of the total UAE population according to the 2005 census.[7]

Etymology

Before the area got the name Abu Dhabi, it was known as Milh, which means salt in Arabic, probably because of the salt water in the area. Milh is still the name of one of the islands in Abu Dhabi.[9]

"Dhabi" is the Arabic name of a particular species of native gazelle, the Arabian gazelle, that was once common in the Arabian region. Abu Dhabi means "the father of the Dhabi". The first use of the name goes back over 300 years. Since the origin of this name has been passed down from generation to generation through poems and legends, it is difficult to know the actual etymology of the name. It is thought that the name came about because of the abundance of gazelles in the area, and a popular folk tale about the founding of the city of Abu Dhabi involving Sheikh Shakhbut bin Dhiyab Al Nahyan.[9][10]

History

Parts of Abu Dhabi were settled millennia ago, and its early history fits the nomadic herding and fishing pattern typical of the broader region. The Emirate shares the historical region of Al-Buraimi or Tawam (which includes modern-day Al Ain) with Oman,[11][12][13][14] and is demonstrated to have been inhabited for over 7000 years.[15]

Modern Abu Dhabi traces its origins to the rise of an important tribal confederation, the Bani Yas, in the late 18th century, which also assumed control of Dubai. In the 19th century, the Dubai and Abu Dhabi branches parted ways.[16]

Into the mid-20th century, the economy of Abu Dhabi continued to be sustained mainly by camel herding, production of dates and vegetables at the inland oases of Al-Ain and Liwa, and fishing and pearl diving off the coast of Abu Dhabi city, which was occupied mainly during the summer months. Most dwellings in Abu Dhabi city were, at this time, constructed of palm fronds (barasti), with the wealthier families occupying mud huts. The growth of the cultured pearl industry in the first half of the twentieth century created hardship for residents of Abu Dhabi as pearls represented the largest export and main source of cash earnings.

In 1939, Sheikh Shakhbut Bin-Sultan Al Nahyan granted petroleum concessions, and oil was first found in 1958. At first, oil money had a marginal impact. A few low-rise concrete buildings were erected, and the first paved road was completed in 1961, but Sheikh Shakbut, uncertain whether the new oil royalties would last, took a cautious approach, preferring to save the revenue rather than investing it in development.[citation needed]

His brother, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, saw that oil wealth had the potential to transform Abu Dhabi. The ruling Nahyan family decided that Sheikh Zayed should replace his brother as ruler and carry out his vision of developing the country. On August 6, 1966, with the assistance of the British, Zayed became the new ruler.[17]

With the announcement by the UK in 1968 that it would withdraw from the area of the Persian Gulf by 1971, Sheikh Zayed became the main driving force behind the formation of the UAE. After the Emirates gained independence in 1971, oil wealth continued to flow to the area, and traditional mud-brick huts were rapidly replaced with banks, boutiques and modern highrises.

Geography

The United Arab Emirates is located in the oil-rich and strategic Arabian or Persian Gulf region. It adjoins the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the Sultanate of Oman.

Abu Dhabi is located in the far west and southwest part of the United Arab Emirates along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf between latitudes 22°40' and around 25° north and longitudes 51° and around 56° east.[18] It borders the emirate of Dubai and emirate of Sharjah to its north.

The total area of the Emirate is 67,340 square kilometres (26,000 square miles), occupying about 87% of the total area of the UAE, excluding islands. The territorial waters of the Emirate embrace about 200 islands off its 700 km (430 mi) coastline. The topography of the Emirate is dominated by low-lying sandy terrain dotted with sand dunes exceeding 300 m (980 ft) in height in some areas southwards. The eastern part of the Emirate borders the western fringes of the Hajar Mountains. Hafeet Mountain, Abu Dhabi's highest elevation and sole mountain,[15] rising 1,100–1,400 m (3,600–4,600 ft),[19][20][21] is located south of Al-Ain City.[18][22]

Land cultivation and irrigation for agriculture and forestation over the past decade has increased the size of "green" areas in the emirate to about 5% of the total land area, including parks and roadside plantations. About 1.2% of the total land area is used for agriculture. A small part of the land area is covered by mountains, containing several caves. The coastal area contains pockets of wetland and mangrove colonies. Abu Dhabi also has dozens of islands, mostly small and uninhabited, some of which have been designated as sanctuaries for wildlife.[23]

Climate

The emirate is located in the tropical dry region. The Tropic of Cancer runs through the southern part of the Emirate, giving its climate an arid nature characterised by high temperatures throughout the year, and a very hot summer. The Emirate's high summer (June to August) temperatures are associated with high relative humidity, especially in coastal areas. Abu Dhabi has warm winters with occasionally low temperatures. The air temperatures show variations between the coastal strip, the desert interior and areas of higher elevation, which together make up the topography of the Emirate.

Abu Dhabi receives scant rainfall but totals vary greatly from year to year. Seasonal northerly winds blow across the country, helping to ameliorate the weather, when they are not laden with dust, in addition to the brief moisture-laden south-easterly winds. The winds often vary between southerly, south-easterly, westerly, northerly and northwesterly. Another characteristic of the Emirate's weather is the high rate of evaporation of water due to several factors, namely high temperature, wind speed, and low rainfall.[18]

The oasis city of Al Ain, about 150 km (93 mi) away, bordering Oman, regularly records the highest summer temperatures in the country; however, the dry desert air and cooler evenings make it a traditional retreat from the intense summer heat and year-round humidity of the capital city.[24]

Government

The emirate's political form is an absolutist, hereditary monarchy. The current ruler of the emirate is Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who began his rein on 14 May 2022, following the death of his brother Sheikh Khalifa. The ruler of Abu Dhabi is tradtionally also elected as the president of the UAE by the Federal Supreme Council, a custom that began with the UAE's first president, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan.[25] Qasr al-Hosn was the palace-fort residence of the ruler and the emirate's seat of government from ca. 1760/1790 to 1966, and later became a museum.[26]

The current crown prince of Abu Dhabi is Sheikh Khalid, a son of the current ruler; the crown prince is assisted in his duties by the Crown Prince's Court, or Diwan. The crown prince traditionally heads the Abu Dhabi Executive Council, which acts as the government of the emirate.[27] The Executive Council includes the chairpersons of Abu Dhabi government departments, who often also head Abu Dhabi state-owned companies and sovereign wealth funds.[28] Abu Dhabi Police is the emirate's primary law enforcement agency and has its own judicial system that is independent from the federal judiciary.

Although no elected parliament exists, the traditional majlis is a form of popular consultation and political participation. The open assembly is held by the emir and members of the royal family, in which any citizen has the right to come and voice their concerns openly.[29]

On the municipal level, each one has their local government under the umbrella of the Department of Municipal Affairs, which divides the emirate into three districts; the Abu Dhabi Capital District Municipality, the Western Region Municipality, and the Eastern Region Municipality. Although the emirate is diversifying its economy, oil is the primary source government funding. Excess reserves are managed by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Mubadala and the Abu Dhabi Holding Company, who invest to diversify the domestic economy and in markets abroad.[30]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 451,848 | — |

| 1985 | 566,036 | +4.61% |

| 1995 | 942,463 | +5.23% |

| 2005 | 1,399,484 | +4.03% |

| 2010 | 1,967,659 | +7.05% |

| 2015 | 2,784,490 | +7.19% |

| Source: Citypopulation[31] | ||

The extraordinary increase in population in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi during the past half-century has made the size, structure and distribution of the population a key concern for future development.

The population of Abu Dhabi reached 1.968 million in mid-2010, with an average annual growth rate of 9.6% since 1960 - among the highest in the world. The total population has increased 99 times in 50 years. The number of citizens increased 39 times and Non-citizens 173 times in the half-century from 1960 to 2010. The most important reason behind the increase in the population growth of citizens is the increase in naturalization (before 1971, and later from other UAE emirates), while immigration constitutes the main factor in increasing the population overall.[7]

The resident population of the Abu Dhabi Emirate exceeded 2 million people in 2011. In mid-year 2011 the estimated population in Abu Dhabi Region was 1.31 million (61.8%), Al Ain Region 0.58 million (27.6%), and Al Gharbia 0.23 million (10.6%), making the total mid-year population for the Abu Dhabi Emirate 2.12 million.[32]

In Abu Dhabi, fertility is higher than in most developed regions of the world, and mortality remains extremely low. In 2011, Crude Birth Rates and Crude Death Rates among Citizens were 15.1 births per 1,000 people and 1.4 deaths per 1,000 people respectively.[32]

| Indicator | 2010[33] | 2011[34] | 2012[35] | 2013[36] | 2014[37] | 2015[38] | 2016[39] | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (mid-year estimate) | 1,967,700 | 2,120,700 | 2,334,600 | 2,453,100 | 2,656,450 | 2,784,490 | 2,908,200 | persons |

| Males | 1,379,600 | 1,499,800 | 1,662,100 | 1,747,800 | 1,766,140 | 1,831,740 | 1,858,200 | persons |

| Females | 558,100 | 620,900 | 672,500 | 705,300 | 890,310 | 952,750 | 1,050,600 | persons |

| Age dependency ratio | 28 | 22.4 | 21.8 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 21.4 | 21.3 | |

| Age dependency ratio, old | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | |

| Age dependency ratio, young | 27 | 21.3 | 20.7 | 20.4 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 20.1 | |

| Urban population | 1,289,247 | 1,292,800 | 1,296,500 | 1,342,600 | 1,618,440 | 1,698,960 | 1,785,460 | persons |

| Rural population | 678,412 | 827,900 | 1,038,100 | 1,110,500 | 1,039,010 | 1,085,530 | 1,112,740 | persons |

| Percentage of the population residing in rural areas | 34.5 | 39 | 44.5 | 45.4 | 39.1 | 39 | 38.3 | |

| Average annual population growth rate | 7.7 | 7.7 | 10 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 | |

| General fertility rate | 80.2 | 80.3 | 78.8 | 78.7 | 62.7 | 58.9 | 53.8 | births per 1000 women

(aged 15 – 49 years) |

| Crude birth rate | 14.9 | 15.1 | 14.6 | 14.7 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 13.7 | per 1000 population |

| Crude death rate | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | per 1000 population |

| Infant mortality rate | 8 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7 | per 1000 live births |

| Under 5 mortality rate | 10 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 8.8 | per 1000 live births |

| Life expectancy at birth for males | 74.9 | 69 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 75.2 | 76 | 75.9 | years |

| Life expectancy at birth for females | 77 | 70 | 78.7 | 78.7 | 78.7 | 79.8 | 79.5 | years |

| Singulate median age at first marriage for males | 26.6 | 26.7 | 27.9 | 26.3 | 28.1 | 28.4 | 28.7 | years |

| Singulate median age at first marriage for females | 25.5 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 23.2 | 25.1 | 25.2 | 25.6 | years |

Largest cities or towns in Abu Dhabi

2023 Calculation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Regions | Pop. | |||||||

Abu Dhabi  Al Ain |

1 | Abu Dhabi | Central | 1,807,000 |  Madinat Zayed  Ruwais | ||||

| 2 | Al Ain | East | 846,747 | ||||||

| 3 | Madinat Zayed | West | 46,862 | ||||||

| 4 | Ruwais | West | 38,740 | ||||||

| 5 | Ghayathi | West | 34,333 | ||||||

| 6 | Liwa | West | 20,192 | ||||||

| 7 | Al Mirfa | West | 9,111 | ||||||

| 8 | Sila | West | 7,900 | ||||||

| 9 | Sweihan | East | 5,403 | ||||||

| 10 | Dalma | West | 5,000 | ||||||

Economy

Abu Dhabi GDP estimates in 2011 amounted to AED 806,031 million at current prices, compared with AED 620,316 million at current prices in 2010. This represents an annual growth rate of 29.9 per cent in 2011. Accordingly, the annual per capita gross domestic product amounted to AED 380.1 thousand in 2011. The total fixed capital formation was AED 199,001 million in 2011, while the compensation of employees amounted to AED 124,960 million in the same year. The main activities contributing to economic growth (GDP at constant prices) in 2011 were "Mining and quarrying" (including crude oil and natural gas), "Financial and insurance" and "Manufacturing" with increases of 9.4 per cent, 10.5 per cent and 9.8 per cent respectively. Commodity imports through the ports of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi were valued at AED 116.4 billion in 2011 compared with AED 86.6 billion in 2010. The main imports during 2011 were machinery and base metals, which accounted for 50.7 per cent of the total value of imports. The United States of America was the main country for imports, from which the Emirate received imports worth AED 13.4 billion. Non-oil exports were valued at AED 11.5 billion, with transport equipment and base metals contributing 61.5 per cent of the total. Canada was the top destination of Abu Dhabi non-oil exports, receiving goods worth AED 2.6 billion from the Emirate in 2011.[18] Mina' Zayid is the main port of Abu Dhabi through which the goods flow.

Al-Ain has one of the few remaining traditional camels souqs in the country, near an IKEA store.[21]

| Item | 2005 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total trade | 226,339.5 | 308,699.4 | 387,275.7* | 532,858.0* |

| Total exports | 191,125.2 | 214,827.2 | 300,702.1* | 416,484.0* |

| Oil, gas and oil products | 184,711.7 | 196,632.2 | 278,105.4* | 393,439.0* |

| Non-oil exports | 3,186.4 | 9,500.8 | 11,610.8 | 11,478.0 |

| Re-exports | 3,227.1 | 8,694.2 | 10,985.9 | 11,567.0 |

| Imports | 35,214.3 | 93,872.2 | 86,573.7 | 116,374.0 |

| Net trade in goods | 155,910.9 | 120,955.0 | 214,128.4* | 300,110.0* |

| * Preliminary estimates |

The Emirate exported 747.2 million barrels of crude oil in 2010. Japan, the top importer, received around 35.6 per cent of the Emirate's total crude oil exports. In 2011, the Emirate exported 10.0 million metric tons of refined petroleum products, of which the Netherlands bought 16.9 per cent, followed by Japan, which purchased 13.9 per cent. One of the main oil pipelines is the Habshan–Fujairah oil pipeline. The Emirate's LNG exports increased by AED 2,973.0 million in 2011 compared with 2010, reaching AED 17,128.2 million. Japan topped the list of importers by 98.4 per cent of the LNG exports value, followed by India by 1.0 per cent in 2011. The Emirate imported 828,093.9 million cubic feet of natural gas in 2011, at a daily average of 2,268.8 million cubic feet.[citation needed]

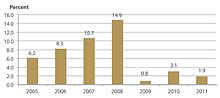

The inflation rate in 2011 was 1.9 per cent. This was a result of an increase in the CPI from 119.3 points in 2010 to 121.6 points in 2011.[18]

The National Bank of Abu Dhabi (NBAD) is the largest lender bank in the emirate and the second-largest lender in the federation. NBAD has the largest market capitalization among UAE banks. The government has put in efforts to diversify the economy and invest in other areas such as the service and tourism industry. The capital city has seen various construction projects and the opening of shopping malls. The opening of the Emirates Palace marked the opening of the most expensive hotel ever built. The annual Abu Dhabi Grand Prix is a Formula One motor race held in the capital city, which further attracts tourists. Apart from the capital city, the Abu Dhabi Desert Challenge is held in the countryside and the tourism board is trying to highlight other places in the emirate.[citation needed]

The Emirate encourages major international film productions which boost employment and the economy in general. A 2019 report stated that the Film Commission provides "30% cashback on production and post-production spend in the Emirate". As a result, film production teams have shot many scenes in Abu Dhabi and in nearby areas, including Mission: Impossible – Fallout, War Machine, and in 2018, 6 Underground.[40] For the filming of the latter movie, the UAE military worked with the crew, providing soldiers as extras as well as aircraft that appear in the film. Production designer Jeffrey Beecroft made this comment: "I’ve shot a lot of military stuff with Michael, but I never had the ability to have six Apache [helicopters], 10 Black Hawks and soldiers".[41]

Sub-divisions and settlements

The Emirate is divided into three municipal regions.[22][42][43] The capital city Abu Dhabi has seen new construction of modern high rises, tall office and apartment buildings, and busy shops. Other urban centres in the emirate are Al-Ain, Baniyas and Ruwais. Al-Ain is an agglomeration of several villages scattered around a desert oasis; today it is the site of the national university, UAEU. In addition, Al-Ain is billed as the "Garden City" of the UAE.[43]

| Region | Map | Settlements |

|---|---|---|

| Abu Dhabi Central Capital District[22][43] Abu Dhabi Metropolitan Area[44][45][46] Abu Dhabi Region[42][47][48] |

|

|

| Al Dhafra Region[54][55][42] Western (Gharbiyyah) Region[56][57] |

|

|

| Al-Ain Region[42][54][55][58] Eastern (Sharqiyyah) Region[56][57] |

|

Transport

Abu Dhabi International Airport (AUH) and Al Ain International Airport (AAN) serve the emirate. The older AUH airport was at Al Bateen Airport. The local time is GMT + 4 hours. Private vehicles, rideshares and taxis are the primary means of transportation in the city, although public buses, run by the Abu Dhabi Municipality, are available, mostly used by the lower-income population. There are bus routes to nearby towns such as Baniyas, Habashan and the garden city of the UAE, Al-Ain, among others. There is a newer service started in 2005 between Abu Dhabi and the commercial city of Dubai (about 150 km (93 mi) away). The government is planning to build a railway in Abu Dhabi.

There are many ports in Abu Dhabi. Khalifa Port is the most recent one.[citation needed]

Education

All private and public schools in the emirate come under the authority of the Abu Dhabi Education Council, while other emirates continue to work under the Federal Ministry of Education. [citation needed]

Schools and universities in Abu Dhabi:

- AAESS

- Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Arab Pakistani School (Kindergarten through 12th-grade FSC)

- Pakistan Community Welfare School

- Abu Dhabi Indian School

- Abu Dhabi Indian School Branch 1, Al Wathba

- Abu Dhabi International School

- Abu Dhabi Men's College (a campus of The Higher Colleges of Technology)

- Abu Dhabi University

- Abu Dhabi Women's College (a campus of The Higher Colleges of Technology)

- Al Bateen Secondary School (British Curriculum)

- The American Community School of Abu Dhabi

- The American International School in Abu Dhabi

- Bright Kids Nursery, Muroor Street

- Emirates College for Advanced Education (ECAE)

- Emirates Future International Academy

- INSEAD Centre in Abu Dhabi

- International School of Choueifat, Abu Dhabi

- Islamia English School (Kindergarten through 12th-grade FSC, IGCSE: O Levels and A Levels also offered)

- Jarn Yafoor Middle School

- Khalifa University of Science, Technology and Research (KUSTAR)

- Masdar Institute of Science and Technology (research-oriented graduate-level university)

- Merryland International, Musaffah

- New York Institute of Technology

- New York University Abu Dhabi

- Paris-Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi

- Shaikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Bangladesh Islamia School

- Sherwood Academy CBSE

- Sherwood Academy IGCSC

- The British School

- The Petroleum Institute

- Zayed University

- Abu Dhabi Grammar School (Canada)

- Al Mushrif

- Al Nahda National Schools (Boys' and Girls' school O Levels, A-Levels, American High school system)

- Al Yasmina School

- Al-Noor Indian Islamic School

- Al Manhal International Private School

- Al Ma'ali International School

- Ashbal Al Quds Private School

- Emirates National School

- First Steps School Nursery

- GEMS American Academy

- Indian Islahi Islamic School

- International Community School

- Khawarizmi International College

- Our Own English High School

- St.Joseph's School

- Strathclyde Business School (MSc/MBA)

- The British School – Al Khubairat

- The Cambridge High School

- The Elite Private School

- The Glenelg School of Abu Dhabi

- The Philippine School, Abu Dhabi

See also

- Mussafah Bridge

- Mussafah Port

- Postage stamps of Abu Dhabi

- Water supply and sanitation in Abu Dhabi

- Wildlife of the United Arab Emirates

References

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2017" (PDF). Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. June 2017. p. 114. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Cullinan, Trevor; Filocca, Giulia; Nair, Purnima (November 24, 2023). "Emirate of Abu Dhabi 'AA/A-1+' Ratings Affirmed; Outlook Stable". S&P Global Ratings. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0

- ^ "Abu Dhabi | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2017" (PDF). Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. June 2017. p. 114. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates | History, Culture, Population, Map, & Capital". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Abu Dhabi Over a Half Century". Statistics Centre - Abu Dhabi (SCAD). Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Gross Domestic Product". Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ a b "How did Dubai, Abu Dhabi and other cities get their names? Experts reveal all". UAE Interact. October 3, 2007. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates". Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Al-Hosani, Hamad Ali (2012). The Political Thought of Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan (PhD Thesis) (Thesis). Durham University. pp. 43–44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Morton, Michael Quentin (April 15, 2016). Keepers of the Golden Shore: A History of the United Arab Emirates (1st ed.). London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-7802-3580-6. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Calvin H. Jr. (February 5, 2016). "1: Land and People". Oman: the Modernization of the Sultanate. Abingdon / New York City: Routledge. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-1-3172-9164-0. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Janet L. Abu-Lughod (contributor) (2007). "Buraimi and Al-Ain". In Dumper, Michael R.T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-5760-7919-5. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Salama, Samir (December 30, 2011). "Al Ain bears evidence of a culture's ability to adapt". Gulf News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ Rugh, Andrea B. (2007). The Political Culture of Leadership in the United Arab Emirates. doi:10.1057/9780230603493. ISBN 978-1-349-53784-6.

- ^ Al-Fahim, M. (1995). "6". From Rags to Riches: A Story of Abu Dhabi. London Centre of Arab Studies. ISBN 1-900404-00-1.

- ^ a b c d e f "Statistics Center". Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ Gardner, Andrew Somerville (January 2004). The reptiles of Jebel Hafeet. ADCO and Emirates Natural History Group. pp. 149–168. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ Lieth, Helmut; Al Masoom, A. A., eds. (December 6, 2012). "Reclamation potentials of saline degraded lands in Abu Dhabi eastern region using high salinity-tolerant woody plants and some salt marsh species". Towards the rational use of high salinity tolerant plants: Vol 2: Agriculture and forestry under marginal soil water conditions. Vol. 2: Agriculture and forestry under marginal soil water conditions. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 271–274. ISBN 978-9-4011-1860-6. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Neild, Barry (October 3, 2018). "Day trip from Abu Dhabi: The cool oasis of Al Ain". CNN. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ^ a b c The Report Abu Dhabi 2016. Oxford Business Group. May 9, 2016. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-9100-6858-8. Archived from the original on January 13, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ Islands of Abu Dhabi Archived October 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sharjah, United Arab Emirates". BBC Weather. Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ "Government in Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi Politics - Allo' Expat Abu Dhabi". Abudhabi.alloexpat.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ Maitra, Jayanti; Hajji, Afra Al- (2001). Qasr Al Hosn: the history of the rulers of Abu Dhabi, 1793-1966. Abu Dhabi: Centre for Documentation and Research. ISBN 978-1-86063-105-4.

- ^ UAEinteract.com. "UAE Government Offices: Abu Dhabi". UAEinteract. Archived from the original on June 2, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ "President Sheikh Mohamed restructures Abu Dhabi Executive Council". The National. March 29, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "UAE Government: Political system - UAEinteract". Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ Abu Omar, Abeer (October 2, 2023). "Abu Dhabi Non-Oil Economy Booms Amid Push to Attract Hedge Funds". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "UAE: Emirates". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Statistics centre − Abu Dhabi". Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2011 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. July 2012. p. 119.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2012. Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. September 2012. p. 118.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2013 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. September 2013. p. 120.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2014 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. September 2014. p. 116.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2015 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. August 2015. p. 112.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2016. Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. August 2016. p. 112.

- ^ Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2017 (PDF). Abu Dhabi: Abu Dhabi Statistics Centre. July 2017. p. 111.

- ^ "twofour54 Abu Dhabi goes behind the scenes of Netflix hit '6 Underground' in exclusive video". twofour54. December 18, 2019. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

"We are proud to have played such an important role in ensuring the shoot went smoothly and seamlessly, demonstrating once again that Abu Dhabi has the infrastructure, talent and expertise to support even the most challenging productions. This end-to-end offering, combined with the generous 30% cash rebate

- ^ "'6 Underground' in Abu Dhabi: new video released from behind the scenes". The National. December 18, 2019. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

'Abu Dhabi was wild to shoot in. Because in our movie it's California, the Middle East, it plays as Hong Kong as well

- ^ a b c d e Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2018 (PDF), Statistics Centre – Abu Dhabi, 2018, p. 171, archived from the original on August 21, 2017, retrieved May 15, 2019

- ^ a b c The Report Abu Dhabi 2010. Oxford Business Group. 2010. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-9070-6521-7. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "List of Abu Dhabi Municipality administrative areas, zones, districts, sectors". Dubai FAQs. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ "Plan Maritime". Department of urban planning and municipalities. 2018. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Plan Abu Dhabi 2030: Urban Structure Framework Plan (PDF), Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council, pp. 1–174, archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2016, retrieved April 3, 2019

- ^ "Abu Dhabi Region Bus Services", Department of Transport, Government of Abu Dhabi, archived from the original on April 2, 2019, retrieved March 22, 2019

- ^ The Report Abu Dhabi 2015. Oxford Business Group. May 9, 2016. pp. 17–31. ISBN 9781910068250. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Bani Hashim, Alamira Reem (2015). Planning Abu Dhabi: From Arish Village to a Global, Sustainable, Arab Capital City (PhD dissertation). University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ "Contractor appointed for $1.4bn Jubail Island project in Abu Dhabi". Arab News. May 19, 2019. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Enabling Works commence on Dh5b Jubail Island". Khaleej Times. May 19, 2019. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ Townsend, Sarah (May 19, 2019). "Jubail Island appoints contractor for Dh5bn Abu Dhabi project". The National. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ Khater, Ismail (April 2013). Certification Systems as a Tool for Sustainable Architecture and Urban Planning Case Study: Estidama, Abu Dhabi (MS thesis). HafenCity University Hamburg. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ a b "Khalifa renames Eastern and Western Regions". WAM. Gulf News. March 16, 2017. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Sheikh Khalifa renames Abu Dhabi regions". The National. March 16, 2017. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ a b "Regional location maps (eastern and western regions of Abu Dhabi emirate)". Ask Explorer. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Unnikrishnan, Deepthi (December 11, 2009). "Abu Dhabi's Eastern Region: few people, bountiful nature". The National. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ "Eastern Region Bus Services", Department of Transport, Government of Abu Dhabi, archived from the original on May 24, 2018, retrieved November 4, 2018

- ^ "Dubai: Crime and accidents down in Al Faqa". Gulf News. April 14, 2014. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ "Population Bulletin" (PDF). Dubai Statistics Center, Government of Dubai. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ Al Wasmi, Naser (May 16, 2018). "Special report: Al Ain farm tackles food and water security by pairing fish with watermelons". The National. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

External links

- Abu Dhabi Police

- Abu Dhabi Chamber of Commerce and Industry

- Universities in Abu Dhabi

- Snow Abu Dhabi

- Newspapers