Contents

Fort Banks was a U.S. Coast Artillery fort located in Winthrop, Massachusetts. It served to defend Boston Harbor from enemy attack from the sea and was built in the 1809 during what is known as the Endicott period, a time in which the coast defenses of the United States were seriously expanded and upgraded with new technology.[1] Today, the fort's mortar battery is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The fort was active during World War II as the site of the Harbor Defense Command Post (HDCP) for the Harbor Defenses of Boston,[2] and was greatly expanded with numerous temporary structures (see 1938 map at top left). Because of its campus-like appearance and the fact that it was located on land, close of Boston, the fort was known as "The Country Club" by Coast Artillery soldiers pleased to be posted there. Fort Banks was named for Nathaniel P. Banks, a Civil War general, the 24th Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Construction

In 1891 construction began on the fort's four mortar pits, each of which was to hold four of the huge, new 12-inch coast defense mortars, each capable of firing a half-ton projectile over six miles out to sea, effectively commanding the northern approaches into Boston Harbor.[3] Construction on the mortar emplacements was completed in 1896,[4] making this the oldest Endicott period fort in Boston's harbor defenses (Battery Adams at Fort Warren was also built in 1891). The two eastern mortar pits were designated as Battery Sanford Kellogg and the two western ones as Battery Benjamin Lincoln, making these the first Endicott gun batteries to be completed in Boston and the first 12-inch coast defense mortar batteries to be completed anywhere in the U.S.[5] The mortars were taken out of service in 1942, and in 2007 the fort was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[6]

The four mortar pits were laid out in a design known as an "Abbot Quad,"[7] which contained the 16 mortars in a sort of "square-of squares." This arrangement was designed such that if all the tubes were aimed in parallel and fired at the same time, in a huge salvo, they would bracket an attacking ship with fire, somewhat like a huge shotgun blast. Since each shell could weigh over half a ton, a 16-mortar salvo of over 8 tons of steel and explosives was hoped to be a decisive deterrent to ships approaching the northern channels into Boston Harbor.[8] In fact, the Army had planned to build two 16-gun Abbot Quad arrays at Fort Banks, but ran out of budget before being able to complete that project.[9]

The Mortars

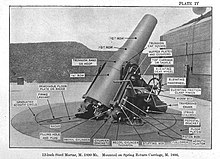

The M1890MI (Model 1890 Modification I) 12-inch mortars at Fort Banks were some of the most powerful coast artillery pieces of their era. The fort was built with generally similar M1886 mortars, but these were replaced with M1890MI mortars in 1911-1915. They were able to fire either high explosive or deck piercing shells. The former weighed 700 lbs each, and the latter weighed in at either 700 or 1,046 lbs. These mortars, firing the heavier shells at an elevation of 45 degrees, had a range of 12,019 yds. (about 7 miles).[10]

Each M1890MI mortar on an M1896 carriage (as at Fort Banks) weighed a total of 78.5 tons and was intricately geared to enable it to be turned (in azimuth) and raised or lowered (in elevation). The shock wave from firing one of these weapons, echoing off the enclosed walls of the mortar pit, was often so strong that it destroyed sensitive equipment mounted near the pit, broke nearby windows, and knocked doors off of nearby structures.[11]

When a mortar battery like those at Fort Banks was fully manned, guidelines called for two mortars in a pit to be manned by a pit commander, two mortar squads of 17 enlisted men each, and an ammunition squad of 16 enlisted men.[12] One of the last versions of the manual[13] for this mortar gives details on how it was crewed and fired.

The photo of Kellogg Pit B at top right clearly shows another unusual feature of the mortar pits—the data booth. This small concrete room, built into the western wall of the pit, with its tapered viewing slits, is visible just left of center in the photo.[14] This booth received and passed to the mortar crews the data (azimuth, elevation, and powder charge) that had been calculated in the plotting room by the Range Unit as settings for the mortars in order for them to hit their targets.[15]

Batteries

The batteries included surface pits, underground magazines, and connecting corridors of the Fort Banks mortar batteries. The mortar pits, flank magazines, and underground corridors are not open to the public.

Battery diagram

The battery diagram is displayed with east at the top. For an idea of scale, the measurement running west from the easternmost (outer) edge of the wall at the top, down the center of the central corridor to the westernmost (outer) edge of the wall at the bottom, is roughly 430 feet. To orient this diagram to the current (2010) surface geography, the point at which the central east-west and north-south galleries cross is approximately here: (42°23′02″N 70°58′51″W / 42.384027°N 70.980747°W).[16]

Looking at the diagram, one can see that the original mortar pit walls, completed in 1896, were much narrower than those that can be seen today (and which were rebuilt in the period 1910-1914). This enlargement of the pits took place because it was found that the smaller design did not allow enough room for the mortars to be properly served.

Originally, the two central (east-west and north-south) corridors completed in 1896 were to have provided the only ammunition and powder storage for the batteries. Indeed, blueprints from 1896 show rows of stored shells drawn-in along these corridors and in some rooms (see 1896 blueprint detail in photo gallery below). A total of some 1248 3-foot shells, 624 3.8-foot shells, and 208 5-foot "torpedoes" were indicated as planned to be stored in the corridors.[17] An extensive system of shell trolleys ran through the magazine rooms and corridors, to transport the heavy shells out to the pits. The 1910-1914 modifications added a series of lever-operated switches to some of these shell trolleys (see two trolley/switch photos in gallery below), so that different stacks of shells could be accessed. The section view in the blueprint image below also illustrates how these shell trolleys were intended to work.

The 1910-1914 work (due to inferior concrete in the original construction) added flank shell and powder storage rooms to both batteries and also a central magazine to Battery Lincoln (see plan above-right, with dimensions). These additional rooms are at the surface on the Battery Lincoln (west) side, but underground for Battery Kellogg (on the east). Although on the Battery Lincoln side the roofs of these magazines are today on the surface, originally all of these magazines were covered with 10 to 20 ft. of earth, as protection against enemy shells and bombs. This new construction expanded the magazines' storage capacity by a tremendous amount. The old (1896) corridors offered about 3,500 sq. ft. of storage. The new work added almost 15,000 sq. ft. of new storage capacity.[18] As part of this rework Battery Lincoln's M1886 mortars were replaced with M1890MI mortars; the same was done with Battery Kellogg's mortars in 1915. During World War I, two mortars each were removed from Pit B of Battery Lincoln and Pit B of Battery Kellogg. This was done to improve the rate of fire of the remaining mortars in the pit; in most cases this was done at all mortar pits, but not at Fort Banks. The removed mortars became potential railway artillery.

World War II

Fort Banks was the WWII location for an anti-aircraft defense command post, a meteorological station, and a bunker holding the "secure" central switchboard for the Harbor Command (see photo in gallery, below).[19] At one time, the fort became the headquarters for the Army's 9th Coast Artillery Regiment, which garrisoned much of the Boston harbor defenses in the early part of WWII. The 241st Coast Artillery Regiment also used the fort as a headquarters. It also had a 250-bed hospital. After the fort was declared surplus by the Army in 1947, its land was purchased by the Town of Winthrop and by private developers for municipal facilities and apartment uses.

Cold War

In the 1950s Nike anti-aircraft missiles were based on the site and in 1959, the Martin AN/FSG-1 Antiaircraft Defense System for the Fort Heath radar station was partly set up at Fort Banks for a SAGE/Missile Master test by NORAD.

Historical marker

A plaque on the site, provided by the Fort Banks Preservation Association and located just outside the portal to Battery Kellogg Pit B, recounts a terrible accident that took place in one of the mortar pits on October 15, 1904, during a practice firing.[20] The plaque indicates that a charge went off prematurely in one of the mortars without the breech of the mortar being closed and locked, killing four and injuring nine others.[21]

Today, the flank magazines of Battery Kellogg are crowded with debris left over from former service as a Town-sponsored "haunted house" at Halloween, and have temporary plywood walls with doors and windows added here and there. Much of this space is occupied by left-over materials stored by the town. On the western (Battery Lincoln) end, the two mortar pits have been filled about halfway up and paved over, and are now used as parking lots (see photo above, at right). The central magazine casemate, which sticks out between the two pits, housed the Harbor Defense Command Headquarters during World War II. The rooms inside this casemate have suffered fire damage (likely from vandals), leaving them littered with charred wood and other debris (see photo below). The rooms of Battery Lincoln's flank magazines have been renovated and are now used by the maintenance department for the nearby condominiums (as shown below). The lower central corridors between the batteries are mostly clear of refuse.

Today, almost all traces of the fort except for the mortar pits and magazines have been destroyed.[22] Of the four mortar pits that originally made up the armament of the fort, only one survives in close to original condition: Pit B of Battery Kellogg (the northeast pit of the quad). A good deal of the original floor of this pit is still visible (see photos in the gallery, below), due to excavations by the town in 1992.[23] The western two pits have been partially filled and then paved over for parking, while the southeast pit (Battery Kellogg, Pit A) has been covered up by a new building. The Winthrop Dept. of Public Works (DPW) now occupies part Battery Kellogg and uses some of the former magazines for storage, while parts of Battery Lincoln are used for offices and storage by property managers for the nearby apartments.

Gallery of additional images

-

A view from inside the data booth of Btty Kellogg Pit B

-

The outside entrance to Battery Kellogg Pit B

-

The bombproof telephone switchboard bunker 42°23′05″N 70°58′52″W / 42.384664°N 70.981048°W

-

One of the former shell rooms in the central magazine, Btty Lincoln

-

The west face of the flank magazines of Btty Lincoln, Pit A

-

Inside view of the Btty Lincoln Pit A flank magazines shows the original doorway openings.

-

Two switches, operated by handles on the wall, moved shells between tracks running along ceiling of a shell room.

-

This "obelisk" on the hill west of Btty Kellogg Pit B is in fact a chimney.42°23′03″N 70°58′51″W / 42.384271°N 70.980735°W

-

A 1938 map of the fort

-

View of Btty Kellogg Pit B looking southwest

-

12-inch mortars (1890 M1) like those at Fort Banks

-

Detail of 1896 plan, showing west end of central magazine

-

A typical view of the central E-W corridor, built in 1896 as a magazine

-

An 1896 shell/powder storage chamber for Btty Kellogg

-

A shell trolley with a switch to move shells from rail to rail

See also

- 9th Coast Artillery (United States)

- 241st Coast Artillery (United States)

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- List of military installations in Massachusetts

References

- ^ Other Coast Artillery forts defending Boston that were built or modernized during this period include Fort Warren on George's Island, Fort Andrews on Peddocks Island, Fort Strong on Long Island, Fort Dawes on Deer Island, and Fort Ruckman in Nahant.

- ^ The HDCP was located in the central above-ground magazine rooms of Battery Lincoln, just west of the end of the 1896 east-west magazine corridor (see plan below).

- ^ At the time, these mortar batteries were considered to be the "wonder weapon" of harbor defense. They could fire special hardened shells in high arcs, enabling these shells to plummet down and pierce the relatively light deck armor of even the heaviest battleships of the period. Furthermore, the mortars were mounted within pits surrounded by tall earthen berms, making them all but untouchable by the relatively low-angle fire of attacking ships lying offshore.

- ^ Extensive modifications were made to the mortar batteries in 1910–1917. See the section on Design below.

- ^ At the time construction began on Ft. Banks, no one had ever built a similar coast defense mortar battery nor fired one of the M1890 mortars in such an emplacement. Fort Warren on Georges Island is the oldest fort in the Boston harbor defense system, having been constructed before the Civil War, but the first of its modern armaments were not completed until 1899. See U.S. Army Engineers, "Reports of Completed Works," various dates.

- ^ The definition of the historic site is somewhat unusual. It is a three-dimensional site that includes the original boundaries of the four mortar pits (one of which is now completely covered by a new apartment structure), and also extends throughout the still-surviving bi-level shell and powder magazines beneath ground. Although the site in fact contains two mortar batteries, the name of the NRHP site only refers to one battery.

- ^ For a description of all the types of U.S. coast defense mortar batteries, battery plans, and a discussion of their differences, see "Analysis of Seacoast Mortar Battery Design Types (1890-1925), by Thomas Vaughan, Version 1.0. Stoughton. MA 27 February 2004.

- ^ Another two batteries of similar mortars were installed a few years later at Fort Andrews on Peddocks Island. These batteries were designed to protect the southern approaches to the harbor, through the channel between Georges Island and Hull, also known as Nantasket Roads.

- ^ There is evidence that the modifications to the four mortar pits which are detailed in the plan shown below were adopted by the Army as a "next-best" strategy for expending available construction funds.

- ^ See "The Service of Coast Artillery," Frank T. Hines and Franklin W. Ward, Goodenough & Woglom Co., New York, 1910, p. 119.

- ^ For this reason, the mortars, which were never fired in combat, were seldom fired in drills either.

- ^ See TR 435-422 "Coast Artillery Corps: Service of the Piece, 12-Inch Mortar (Fixed Armament), U.S. War Dept., Washington, D.C., December 24, 1924, p. 2.

- ^ 1942 version of the mortar manual

- ^ During the remodeling of 1904-1910, the data booths for Battery Lincoln were converted into small, free-standing "pillboxes," located on top of the earthen cover for the battery.

- ^ Since the mortar crews down in the pits could not see to aim their weapons, remote spotters located the targets and passed their coordinates to a plotting room for each battery, which computed the target's position on a plotting board. The proper azimuth and elevation for each pit (or later, for each mortar) was posted on a small "billboard" that hung outside the data booth, where it could easily be seen by each mortar crew out in the pit. This billboard also indicated the number of the zone for the target, equivalent to the size of the powder charge that should be used in the mortar to achieve the necessary range. Zone 3 was the smallest charge, and Zone 10 was the largest. The crews would strap together the required number of powder packets for the zone listed, attach an igniter packet to the base of the stack, and place this powder load into the breech of the mortar, behind the shell.

- ^ The location of this point was estimated by measuring on Vaughan's original blueprint the distance from the northeast corner of Kellogg Pit B to the central point and taking a bearing along this line (about 238 ft. at 245 degrees true). This information was transferred to a Google Map and the coordinates of the resulting point were read off the map cursor on Google. This point is thought to have a circular error of about 6 feet or so. This is consistent with a point about 5 feet distant from it that marks the former location of a U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (USCGS) survey mark (MY4776) for the directing point of Battery Kellogg and was described (in 1940) as roughly at the center of the intersection of the two berms on the surface that separated the four mortar pits.

- ^ The "torpedoes" were thin-walled steel shells containing about 130 lbs. of explosive, designed to detonate upon impact with a ship's deck and scatter shrapnel among the crew. The shells described for this mortar in the 1942 manual (see Note 12, supra) included a 3ft. 824lb. deck-piercing shell, 700lb. high explosive shells ranging in length from 3.75ft. to 4.22ft., and 1046lb. deck-piercing shells that were 4.1ft. long.

- ^ Later on, some of the additional space was used (during World War II) to house the harbor defense command headquarters and a rifle range.

- ^ The 1938 map of the fort (see gallery) shows this bunker as being located just north of Battery Lincoln, Pit B, as indicated by the cross-hatched square with the diagonal line through its center. This bunker is today (in 2010) accessible from the DPW parking lot, through the portal shown in the photo above.

- ^ No Coast Artillery armament in the continental United States was ever fired in battle; only practice firings were conducted.

- ^ The Boston Daily Globe of October 16, 1904, reported that the explosion blew the mortar's breech block through the pit, decapitating one of the crew and blowing his head up through the tube of a nearby mortar. The breech block then severely maimed two more men before ricocheting off and striking the wall of the pit. The accident occurred during the first firing of the mortar that day, so it was speculated that a bit of burning powder bag from an earlier firing of a nearby mortar had somehow floated down on the power bag used for the practice charge, smoldering there and later detonating the bag prematurely.

- ^ All the surface structures listed in the legends of the map shown at top left have been demolished, an immense amount of earth has been stripped off the top of the mortar batteries (see map c.1940 for a view of the original topography), and the land has been redeveloped.

- ^ Today, the Town of Winthrop stores granite curbing inside the pit. The ramp from street level down into the pit was added during the 1992 excavation. Previously the pit could be entered directly from the outside only through the portal pictured in the photo gallery below.

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

External links

- CoastDefense.com provides an overview of the coast defenses of Boston Harbor.

- Fort Banks at FortWiki.com

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- Harbor Defenses of Boston at NorthAmericanForts.com