Contents

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| ||

The 2000 presidential campaign of John McCain, the United States Senator from Arizona, began in September 1999. He announced his run for the Republican Party nomination for the presidency of the United States in the 2000 presidential election.

McCain was the main challenger to Texas Governor George W. Bush, who had the political and financial support of most of the party establishment. McCain staged an upset win in the February 2000 New Hampshire primary, capitalizing on a message of political reform and "straight talk" that appealed to moderate Republican and independent voters and to the press. McCain's momentum was halted when Bush won the South Carolina primary later that month, in a contest that became famous for its bitter nature and an underground smear campaign run against McCain.

McCain won some subsequent primaries, but after the March 2000 Super Tuesday contests he was well behind in delegates and withdrew. He reluctantly endorsed Bush two months later and made occasional appearances for him during the general election.

Leading up to the announcement

McCain was mentioned as a possible candidate for the Republican nomination beginning in 1997, but he took few steps to pursue it, instead concentrating on his 1998 senate re-election.[1] The decision of General Colin Powell not to run helped persuade McCain that there might be an opening for him.[2] McCain later wrote that he had a "vague aspiration" of running for president for a long time.[3] He would also be candid about his motivation: "I didn't decide to run for president to start a national crusade for the political reforms I believed in or to run a campaign as if it were some grand act of patriotism. In truth, I wanted to be president because it had become my ambition to become president. I was sixty-two years old when I made the decision, and I thought it was my one shot at the prize."[3]

Potential weaknesses of a McCain candidacy included his senatorial accomplishments skewing towards the maverick side rather than those that would appeal to the party core, a lack of funds and of fund-raising prowess, and an unpredictability of personality and temperament.[1] Potential assets included favorable treatment in the political media, as well as being featured on A&E's Biography series, and support from veterans.[1] National polls showed McCain with low name recognition, but once voters were asked about a hypothetical candidate with a similar military biography, the numbers improved dramatically.[2]

Announcements and Kosovo

McCain had initially planned on announcing his candidacy and beginning active campaigning on April 6, 1999.[4] There was to be a four-day roadshow, whose first day would symbolically begin at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, then see early primary states New Hampshire and South Carolina, before concluding in home Phoenix, Arizona[4] with a big audience, marching bands, and thousands of balloons.[5]

However, the Kosovo War intervened. On March 24, the NATO bombing campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia began. McCain had voted the day before in favor of approval for the Clinton administration's action, saying "Atrocities are the signature of the Serbian Army. They've been carrying out atrocities since 1992. We must not permit the genocide that Milosevic has in mind for Kosovo to continue. We are at a critical hour."[6] He was critical of past inaction by the Clinton administration in the matter,[6] and within days was urging that the use of ground troops not be ruled out.[7] McCain became a very frequent guest on television talk shows discussing the conflict, and his "We are in it, now we must win it" stance drew much attention.[7][8] On March 31, three American soldiers were captured by Yugoslavia;[9] the next day, McCain canceled his planned roadshow, stating "this is not an appropriate time to launch a political campaign."[7][10] He received media praise for his action and continued to be a highly visible spokesman for strong action regarding Kosovo;[7] CNN pundit Mark Shields said that, "In thirty-five years in Washington, I have never seen a debate dominated by an individual in the minority party as I've seen this one dominated by John McCain."[7]

On April 13, McCain simply issued a statement without fanfare that he would be a candidate:[11] "While now is not the time for the celebratory tour I had planned, I am a candidate for president and I will formally kick off my campaign at a more appropriate time."[11] McCain and his wife Cindy would make some campaign-related appearances over the spring and summer.[12]

McCain's co-authored, best-selling[13] family memoir, Faith of My Fathers, published in August 1999, helped promote the new start of his campaign.[14] The book garnered largely positive reviews,[15] and McCain went on a 15-city book tour during September.[15] The tour's success and the book's high sales led to the themes of the memoir, which included McCain talking more about his Vietnam prisoner-of-war experience than he had in the past, becoming a major part of McCain's campaign messaging.[16]

McCain finally formally announced his candidacy on September 27, 1999, before a thousand people in Greeley Park in Nashua, New Hampshire,[8][17] saying "It is because I owe America more than she has ever owed me that I am a candidate for president to the United States."[8] He further said he was staging "a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve."[14] As originally planned, he began his announcement day with a visit to the Naval Academy.[8]

Campaign staff and policy team

McCain's campaign used many veteran Washington political insiders, including some who had an insurgency-oriented or contrarian mindset.[2] Rick Davis was the campaign manager for the McCain effort, while Mike Murphy was the overall strategist and John Weaver the chief political adviser.[18] Greg Stevens was the media adviser and Mark Salter was the chief speechwriter (and credited co-author of McCain's books).[18] Howard Opinsky was the campaign's press officer.[18] Craig Turk was the general counsel.[19]

After a while, a rivalry formed between Davis, at campaign headquarters, and Weaver and Murphy, who traveled on the campaign bus.[19] Davis wanted a larger role in campaign strategy, and eventually differences between the two factions escalated to attacks made via the press.[19]

Campaign developments 1999

There was a crowded field of Republican candidates, but the big leader in terms of establishment party support and fundraising was Texas Governor and presidential son George W. Bush.[20][21][22] Indeed, by the time of McCain's formal announcement, top-echelon Republican contenders such as Lamar Alexander, John Kasich, and Dan Quayle were already withdrawing from the race due to Bush's strength.[20] As McCain would later write, "No one thought I had much of a chance, including me."[23] Four of McCain's fifty-five fellow Republican senators endorsed his candidacy.[24]

The day after McCain announced, Bush made a show of visiting Phoenix and displaying that he, not McCain, had the endorsement of Arizona Governor Jane Dee Hull and several other prominent local political figures.[14] McCain did have the support of the rest of the Republican Arizona congressional delegation.[25] Hull would continue to attack McCain during the campaign, and was featured in high-profile Arizona Republic and New York Times stories about McCain's reputation for having a bad temper,[14][26] with the latter featuring on-the-record criticism from Governor of Michigan John Engler.[26] By early November, stories about McCain's temper problem were frequent enough that Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz wrote a survey article about them.[27] Some of McCain's opponents, including those in or close to the Senate Republican leadership, intimated that McCain's temper was a sign of mental instability.[28] The notion that this was due to McCain's POW days caused Admiral James Stockdale, a fellow former POW and 1992 vice-presidential candidate for Ross Perot, to write an op-ed piece for The New York Times, "John McCain in the Crucible".[29] In it, Stockdale said that the reverse was true: that the experience of resisting during the POW experience made former POWs more emotionally stable in later life, not less.[30] In early December, McCain released some 1,500 pages of his medical and psychiatric records,[31] which showed several psychiatric evaluations over a number of years following his POW release that indicated no signs of lingering mental or emotional difficulty from that period.[32][33]

Bush avoided most of the scheduled Republican Party debates during 1999,[34] including one held on November 21 at Arizona State University in McCain's home state.[34] There McCain debated second-tier candidates Alan Keyes, Orrin Hatch, and Steve Forbes instead.[34] Bush finally did participate in the December 6 debate from the Orpheum Theatre in Phoenix, by which time McCain was so busy campaigning in New Hampshire that he had to join via a video linkup.[35] There McCain's signature push for campaign finance reform led to one of the few lively exchanges in an otherwise placid event.[35]

Following political consultant Mike Murphy's advice,[36] McCain decided to skip the initial event of the nomination season, the Iowa caucus, where his long opposition to ethanol subsidies would be unpopular[24] and his late start and lack of base party support would hurt him in the grassroots organizing necessary for success in the state.[37] (He had earlier skipped the August 1999 Iowa Straw Poll, labeling it a sham.[12]) McCain focused on introducing his biographical story, especially his Vietnam and POW experiences; a videocassette telling the story was sent to 50,000 voters in the first two primary states, as well as to military veterans in other states.[38]

Caucuses and primaries 2000

New Hampshire

By skipping Iowa, McCain was able to focus instead on the New Hampshire primary, where his message held appeal to independents and where Bush's father had never been very popular.[36] At first, McCain attracted small crowds and little media attention.[24] But by November 1999, McCain had become competitive, measuring evenly with Bush in polls.[39] Bush said he realized McCain was a strong candidate there: "If I had to guess why Senator McCain is doing well, it's people respect him and so do I. He's a good man."[39]

McCain traveled on a campaign bus called the Straight Talk Express, whose name capitalized on his reputation as a political maverick who would speak his mind. In visits to towns he gave a ten-minute talk focused on campaign reform issues, then announced he would stay until he answered every question that everyone had. He pledged that "I will never tell you a lie."[24] He conducted 114 of these town hall meetings,[40] speaking in every town in New Hampshire in an example of "retail politics" that overcame Bush's familiar name. His growing number of supporters became known as "McCainiacs".[41]

McCain was famously accessible to the press, using free media to compensate for his lack of funds.[2][14] As one reporter later recounted, "McCain talked all day long with reporters on his Straight Talk Express bus; he talked so much that sometimes he said things that he shouldn't have, and that's why the media loved him."[42] Some McCain aides saw the senator as naturally preferring the company of reporters to other politicians.[2]

McCain and Bush argued over their proposals for tax cuts; McCain criticized Bush's plan as too large and too beneficial to the wealthy.[43] McCain preferred a smaller cut that would allocate more of the surplus towards the solvency of Social Security and Medicare.[43] McCain pushed his signature issue of campaign finance reform, and was the only candidate to talk much about foreign policy and defense issues.[24]

On February 1, 2000, McCain won the primary with 49 percent of the vote to Bush's 30 percent, and suddenly was the focus of media attention.[24] Other Republican candidates had dropped out or failed to gain traction, and McCain became Bush's only serious opponent. Analysts predicted that a McCain victory in the crucial South Carolina primary might give his insurgency campaign unstoppable momentum;[44][45][46] a degree of fear and panic crept into not only the Bush campaign[14] but also the Republican establishment and movement conservatism.[45][46] Bush's top campaign staff met and strategized what to do about McCain; one advisor said, "We gotta hit him hard."[47]

South Carolina

The battle between Bush and McCain for South Carolina has entered U.S. political lore as one of the nastiest, dirtiest, and most brutal ever.[14][48][49] On the one hand, Bush switched his label for himself from "compassionate conservative" to "reformer with results", as part of trying to co-opt McCain's popular message of reform.[14][50][51] On the other hand, a variety of business and interest groups that McCain had challenged in the past now pounded him with negative ads.[14][52]

The day that a new poll showed McCain five points ahead in the state,[53] Bush allied himself on stage with a marginal and controversial veterans activist named J. Thomas Burch, who accused McCain of having "abandoned the veterans" on POW/MIA and Agent Orange issues: "He came home from Vietnam and forgot us."[14][53] Incensed,[53] McCain ran ads accusing Bush of lying and comparing the governor to Bill Clinton,[14] which Bush complained was "about as low a blow as you can give in a Republican primary"; many Republicans thought comparing Bush's truthfulness to Bill Clinton's dishonesty was distasteful smear by McCain.[14] An unidentified party began a semi-underground smear campaign against McCain, delivered by push polls, faxes, e-mails, flyers, audience plants, and the like.[14][54] These claimed most famously that he had fathered a black child out of wedlock (the McCains' dark-skinned daughter Bridget was adopted from Bangladesh; this misrepresentation was thought to be an especially effective slur in a Deep South state where race was still central[49]), but also that his wife Cindy was a drug addict, that he was a homosexual, and that he was a "Manchurian Candidate" traitor or mentally unstable from his North Vietnam POW days.[14][48] The Bush campaign strongly denied any involvement with these attacks;[48] Bush said he would fire anyone who ran defamatory push polls.[55] During a break in a debate, Bush put his hand on McCain's arm and reiterated that he had no involvement in the attacks; McCain replied, "Don't give me that shit. And take your hands off me."[47]

Bush mobilized the state's evangelical voters,[14][24] and leading conservative broadcaster Rush Limbaugh entered the fray supporting Bush and claiming McCain was a favorite of liberal Democrats.[56] Polls swung in Bush's favor; by not accepting federal matching funds for his campaign, Bush was not limited in how much money he could spend on advertisements, while McCain was near his limit.[56] With three days to go, McCain shut down his negative ads against Bush and tried to stress a positive image.[56] But McCain's stressing of campaign finance reform, and how Bush's proposed tax cuts would benefit the wealthy, did not appeal to core Republicans in the state.[24]

McCain lost South Carolina on February 19, with 42 percent of the vote against Bush's 53 percent,[57] allowing Bush to regain the momentum.[57]

On to Super Tuesday

McCain's campaign never completely recovered from his defeat in South Carolina.[14] He did rebound partially by winning in Arizona and Michigan on February 22,[58] mocking Governor Hull's opposition in the former.[14] In Michigan, which he won 50 percent to 43 percent in an upset,[24] he captured many Democratic and independent votes,[58] who combined made up over half of the primary electorate.[24]

Still reeling from his South Carolina experience, McCain made a February 28 speech in Virginia Beach that criticized Christian leaders, including Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, as divisive;[48] McCain declared, "... we embrace the fine members of the religious conservative community. But that does not mean that we will pander to their self-appointed leaders."[59] He also made an off-the-cuff, unserious remark on the Straight Talk Express that referred to Robertson and Falwell as "forces of evil", that came across as angry hostility to many Christian conservatives.[24] McCain lost the Virginia primary on February 29, as well as one in Washington.[60]

McCain had stated in mid-February that "I hate the gooks", referring to his captors during the Vietnam War.[61] This use gained some media attention in California, which had a large Asian American population.[61] After criticism from some in that community, McCain vowed to no longer use the term, saying, "I will continue to condemn those who unfairly mistreated us. But out of respect to a great number of people for whom I hold in very high regard, I will no longer use the term that has caused such discomfort."[62] Reaction among Vietnamese Americans to McCain's use of this term was mixed although supportive of McCain himself,[63][64][65] and exit polls in the primary in California showed that they strongly supported him.[66] This was not the first or the last example of controversial remarks by McCain.

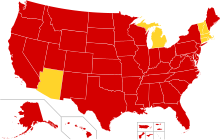

A week later on March 7, 2000, he lost nine of the thirteen primaries on Super Tuesday to Bush, including large states such as California, New York, Ohio, and Georgia; McCain's wins were confined to the New England states of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and Vermont.[67] His overall loss on that day has been attributed to his going "off message", ineffectively accusing Bush of being anti-Catholic due to having visited Bob Jones University[68] and getting into a verbal battle with leaders of the Religious Right.[69]

Withdrawal

Throughout the campaign, McCain had achieved parity with Bush among self-identified Republicans only in the northeastern states; in most of the rest of the country, Bush ran way well ahead of McCain among Republicans, enough to overcome McCain's strength among independents and Democrats.[24]

With little hope of overcoming Bush's delegate lead after Super Tuesday, McCain withdrew from the race on March 9, 2000.[70] In his remarks before a crowd of supporters and onlookers with the red rocks of Sedona, Arizona as a backdrop,[71] McCain said that "When we began this campaign, we knew that ours was a difficult challenge" but that now the challenge had become "considerably more difficult" and that it was time to stop.[70] Nevertheless, he said he would not abandon the idea of political reform that the campaign had embraced, saying "I will never walk away from a fight for what I know is right and just for our country."[71]

General election

Following the end of his campaign, McCain returned to the Senate, where he was welcomed with respect for the effort he had made, his openness in the campaign, and the attacks he had undergone.[72] Other Republicans sought out his endorsement in their general election races.[72] In the Senate, McCain continued his push for campaign finance reform.[73] The question of whether McCain would endorse Bush remained uncertain.[73]

The events of South Carolina stayed with McCain. In an interview during this time, McCain would say of the rumor spreaders, "I believe that there is a special place in hell for people like those,"[74] and in another interview he called the rumor spreaders "the ugly underside of politics."[75] McCain regretted some aspects of his own campaign there as well, in particular changing his stance on flying the Confederate flag at the state capitol from a "very offensive" "symbol of racism and slavery" to "a symbol of heritage".[14][48] He would later write, "I feared that if I answered honestly, I could not win the South Carolina primary. So I chose to compromise my principles."[48] He had done so woodenly, reading his revised statement from a piece of paper.[76] According to one report, the South Carolina experience overall left McCain in a "very dark place."[48]

McCain finally did announce he would campaign for Bush, in a joint appearance with him on May 9, but did not use the actual word "endorse" until reporters pressed him to do so.[24][77][78] The Guardian characterized the endorsement as "tepid" and said that McCain "betrayed little outward enthusiasm" during the appearance,[78] while The New York Times wrote that "there was a tight, grudging quality to the event," and that McCain had been "looking a bit like a teenager forced to attend a classical music concert."[79] McCain also made it clear that he was not interested in a vice-presidential nomination.[24]

When the 2000 Republican National Convention began in Philadelphia at the end of July, McCain took his Straight Talk Express to meet with his delegates and supporters before formally releasing them to Bush. There were tears from McCain, his wife Cindy, and some of the campaign staff and delegates.[80] Many of McCain's supporters were vocally unhappy with his words of support for Bush, and the Times wrote that, "Politics as usual with its compromises, cruelties and emotional costs—caught up with Senator John McCain this weekend."[80] McCain made a point of having Cindy McCain head the Arizona delegation at the convention, not his antagonist Governor Hull.[24] On August 1, the second night of the convention, McCain delivered a speech in praise of Bush, in particular trying to solidify Bush's national security and foreign policy credentials.[81] In it, McCain connected his family to Bush's, making reference to former President George H. W. Bush's combat service as a naval aviator in the Pacific Theater of World War II under Admiral John S. McCain, Sr., McCain's grandfather.[14] He said directly of the nominee, "I support him. I am grateful to him. And I am proud of him."[14] The Almanac of American Politics called it "a moving, elegiac speech that ended as if in a minor key."[24]

McCain's plans to campaign for Bush in fall 2000 were delayed later in August by a recurrence of melanoma.[14] This Stage IIa instance on his temple required extensive surgery that removed the lesion, surrounding lymph nodes, and part of the parotid gland.[82] The final pathology tests showed that the melanoma had not spread, and his prognosis was good, but McCain was left with cosmetic aftereffects including a puffy cheek and a scar down his neck.[82]

McCain did join Bush for a few days of appearances in late October,[83] emphasizing, in the wake of the October 12 USS Cole bombing, his belief that Bush was a better choice than Democratic Party nominee Al Gore to deal with international security threats.[14] Bush aide Scott McClellan later described the joint appearances by saying, "The tension was palpable. The two were cordial, but McCain would get that forced smile on his face whenever they were together."[47] McCain also campaigned for about forty Republican House of Representatives candidates, and was credited by National Republican Congressional Committee chair Tom Davis with keeping the House in Republican hands.[84] McCain would state that he voted for Bush on November 7 (although years later several witnesses would relate that McCain and his wife Cindy had both said at a dinner party that they had not).[85] When the November presidential election continued on in indecision during the Florida election dispute, McCain stayed generally quiet in an atmosphere of extreme partisanship,[86] though he did appear on CBS' Face the Nation to say, "I think the nation is growing a little weary of this. We're not in a constitutional crisis, but the American people are growing weary, and whoever wins is having a rapidly diminishing mandate, to say the least."[87] Once Bush was declared the winner and inaugurated in January 2001, McCain's battles with him would resume,[47][86] with a significant amount of lingering bitterness between the two men and their staffs over what had transpired during the course of 2000.[88]

Aftermath

South Carolina investigated and revisited

While South Carolina was known for legendary hard-knuckled political consultant Lee Atwater[49] and rough elections,[48] this had been rougher than most. Michael Graham, a native writer, radio host, and political operative, would say "I have worked on hundreds of campaigns in South Carolina, and I've never seen anything as ugly as that campaign."[89] In subsequent years there would be persistent accounts trying to tie the anti-McCain smears to high levels of the Bush campaign: the 2003 book Bush's Brain would use it to build up their "evil genius" depiction of Bush chief strategist Karl Rove,[90] while a 2008 NOW on PBS program showed a local political consultant stating that Warren Tompkins, a Lee Atwater protégé and then Bush chief strategist for the state, was responsible.[49][91] In contrast, in 2004 National Review's Byron York would try to debunk many of the South Carolina smear reports as unfounded legend.[92] McCain's campaign manager said in 2004 they never found out where the smear attacks came from,[93] while McCain himself never doubted their existence.[14]

When McCain ran for president again in 2008, South Carolina again proved crucial, in his battle with former Governors Mitt Romney and Mike Huckabee and former Senator Fred Thompson. This time, McCain had the support of much of the state Republican establishment[94] (although Rush Limbaugh and other talk radio figures were still lambasting him),[95] and aggressively moved to thwart any smear campaign before it got started.[96] McCain won the primary on January 19, 2008; in his victory remarks to supporters that evening, he said, "It took us awhile, but what's eight years among friends?"[97] The New York Times described McCain's win as "exorcising the ghosts of the attack-filled primary here that derailed his presidential hopes eight years ago."[97]

Primary campaign results

Total popular votes in Republican 2000 primaries:[98]

- George W. Bush – 12,034,676 (62.0%)

- John McCain – 6,061,332 (31.2%)

- Alan Keyes – 985,819 (5.1%)

- Steve Forbes – 171,860 (0.9%)

- Unpledged – 61,246 (0.3%)

- Gary Bauer – 60,709 (0.3%)

- Orrin Hatch – 15,958 (0.1%)

Key states:[98]

- Feb 1 New Hampshire primary: McCain 115,606 (48.5%), Bush 72,330 (30.4%), Forbes 30,166 (12.7%), Keyes 15,179 (6.4%)

- Feb 19 South Carolina primary: Bush 305,998 (53.4%), McCain 239,964 (41.9%), Keyes 25,996 (4.5%)

- Feb 22 Arizona primary: McCain 193,708 (60.0%), Bush 115,115 (35.7%), Keyes 11,500 (3.6%)

- Feb 22 Michigan primary: McCain 650,805 (51.0%), Bush 549,665 (43.1%), Keyes 59,032 (4.6%)

- Feb 29 Virginia primary: Bush 350,588 (52.8%), McCain 291,488 (43.9%), Keyes 20,356 (3.1%)

- Feb 29 Washington primary: Bush 284,053 (57.8%), McCain 191,101 (38.9%), Keyes 11,753 (2.4%)

- Mar 7 California primary: Bush 1,725,162 (60.6%), McCain 988,706 (34.7%), Keyes 112,747 (4.0%)

- Mar 7 New York primary: Bush 1,102,850 (51.0%), McCain 937,655 (43.4%), Keyes 71,196 (3.3%), Forbes 49,817 (2.3%)

- Mar 7 Ohio primary: Bush 810,369 (58.0%), McCain 516,790 (37.0%), Keyes 55,266 (4.0%)

- Mar 7 Georgia primary: Bush 430,480 (66.9%), McCain 179,046 (27.8%), Keyes 29,640 (4.6%)

- Mar 7 Missouri primary: Bush 275,366 (57.9%), McCain 167,831 (35.3%), Keyes 27,282 (5.7%)

- Mar 7 Maryland primary: Bush 211,439 (56.2%), McCain 135,981 (36.2%), Keyes 25,020 (6.7%)

- Mar 7 Maine primary: Bush 49,308 (51.0%), McCain 42,510 (44.0%), Keyes 2,989 (3.1%), Uncommitted 1,038 (1.1%)

- Mar 7 Massachusetts primary: McCain 325,297 (64.7%), Bush 159,826 (31.8%), Keyes 12,656 (2.5%)

- Mar 7 Vermont primary: McCain 49,045 (60.3%), Bush 28,741 (35.3%), Keyes 2,164 (2.7%)

- Mar 7 Rhode Island primary: McCain 21,754 (60.2%), Bush 13,170 (36.4%), Keyes 923 (2.6%)

- Mar 7 Connecticut primary: McCain 87,176 (48.7%), Bush 82,881 (46.3%), Keyes 5,913 (3.3%)

References

- ^ a b c Timberg, Robert (1999). John McCain: An American Odyssey. Touchstone Books. ISBN 0-684-86794-X. pp. 192–94.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas, Evan and Isikoff, Michael (2000-03-06). "How McCain Does It". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b McCain, John; Salter, Mark (2002). Worth the Fighting For. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-50542-3. p. 373.

- ^ a b Timberg, An American Odyssey, p. 199.

- ^ Alexander, Paul (2002). Man of the People: The Life of John McCain. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-22829-X. p. 190.

- ^ a b Greg McDonald (1999-03-23). "Senate OKs use of force in Balkans". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ a b c d e Timberg, An American Odyssey, pp. 200–02.

- ^ a b c d "McCain formally kicks off campaign". CNN.com. 1999-09-27. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ "Captured U.S. soldiers face military court in Yugoslavia". CNN. 1999-04-02. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ^ "Sen. McCain delays announcement for presidency". CNN.com. 1999-04-02. Archived from the original on November 28, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ a b "McCain says 'I am a candidate'". CNN.com. 1999-04-13. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 192–93.

- ^ "Faith of My Fathers (1999)". Books and Authors. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Dan Nowicki; Bill Muller (2007-03-01). "John McCain Report: The 'maverick' runs". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 194–95.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (2008-10-12). "Writing Memoir, McCain Found a Narrative for Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Man of the People, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Jason Zengerle (2008-04-23). "Papa John". The New Republic. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ^ a b Frank Bruni (2000-09-27). "Quayle, Outspent by Bush, Will Quit Race, Aide Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Timberg, An American Odyssey, p. 197.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. 217.

- ^ McCain, Worth the Fighting For, p. 369.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Barone, Michael; Cohen, Richard E. (2007). The Almanac of American Politics (2008 ed.). Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-89234-117-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) pp. 96–97. - ^ Alter, Jonathan (1999-11-15). "White Tornado". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ a b Richard L. Berke (1999-10-25). "McCain Having to Prove Himself Even in Arizona". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. 203.

- ^ Drew, Elizabeth (2002). Citizen McCain. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-641-57240-9. p. 23.

- ^ James Stockdale (1999-11-26). "John McCain in the Crucible". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2008-02-04. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. 206.

- ^ Lawrence K. Altman (1999-12-06). "Release of McCain's Medical Records Provides Unusually Broad Psychological Profile". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. 208.

- ^ Nancy Gibbs; John F. Dickerson (1999-12-06). "The power and the story". Time. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ a b c "GOP presidential hopefuls begin debate in Arizona". CNN.com. 1999-11-21. Archived from the original on May 19, 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ a b "Flattery more common than conflict in Arizona debate". CNN.com. 1999-12-06. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 188–89.

- ^ David Yepsen (1999-11-17). "McCain formalizes decision to skip Iowa caucuses". Des Moines Register. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Parmelee, John (July 2002). "Presidential Primary Videocassettes: How Candidates in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Primary Elections Framed Their Early Campaigns". Political Communication. 19 (3): 317–31. doi:10.1080/01957470290055529. S2CID 144157660.

- ^ a b "Polls: McCain ties Bush in New Hampshire; Bradley gains support in New York, Iowa". CNN.com. 1999-11-11. Archived from the original on December 12, 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ McCain, Worth the Fighting For, p. 371.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, p. ix.

- ^ Harpaz, Beth (2001). The Girls in the Van: Covering Hillary. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30271-1. p. 86.

- ^ a b "Bush, McCain continue to snipe over tax cuts, but is anybody listening?". CNN.com. 2000-01-19. Archived from the original on March 2, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Jeff Greenfield (2000-02-08). "Random thoughts of a McCain operative". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b Jonah Goldberg (2000-02-11). "Love Is a Two-Way Street". National Review Online. Archived from the original on 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b David Corn (2000-02-10). "The McCain Insurgency". The Nation. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b c d Carney, James (2008-07-16). "Frenemies: The McCain-Bush Dance". Time. Archived from the original on July 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jennifer Steinhauer (2007-10-19). "Confronting Ghosts of 2000 in South Carolina". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b c d "Dirty Politics 2008". NOW on PBS. Public Broadcasting Service. 2008-01-04. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Alison Mitchell (2000-02-10). "Bush and McCain Exchange Sharp Words Over Fund-Raising". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 259–60.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 254–55, 262–63.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 250–51.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 263–66.

- ^ Mike Ferullo (2000-02-10). "'Push polling' takes center stage in Bush-McCain South Carolina fight; Dems campaign in California". CNN. Archived from the original on April 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ a b c Alison Mitchell (2000-02-16). "McCain Catches Mud, Then Parades It". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b Brian Knowlton (2000-02-21). "McCain Licks Wounds After South Carolina Rejects His Candidacy". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b Ian Christopher McCaleb (2000-02-22). "McCain recovers from South Carolina disappointment, wins in Arizona, Michigan". CNN.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2008. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ "Excerpt From McCain's Speech on Religious Conservatives". The New York Times. 2000-02-29. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Stuart Rothernberg (2000-03-01). "Stuart Rothernberg: Bush Roars Back; McCain's Hopes Dim". CNN.com. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ a b Nevius, CW (2000-02-18). "McCain Criticized for Slur: He says he'll keep using term for ex-captors in Vietnam". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ Ma, Jason (2000-02-14). "McCain Apologizes for 'Gook' Comment". Asian Week. Archived from the original on 2000-11-02. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ Pasco, Jean (2000-03-02). "A Hero's Welcome for McCain in Little Saigon; Politics: Some Vietnamese protest senator's slur but most cheer candidate. Ex-POW salutes comrades in arms". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Bunis, Dena (2000-03-02). "McCain's visit stirs admiration". The Orange County Register.

- ^ Dang, Janet (2000-02-24). "Vietnamese American Reaction Divided". Asian Week. Archived from the original on 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Vik Jolly (March 10, 2000). "McCain easy winner among Vietnamese in O.C.". The Orange County Register.

- ^ Ian Christopher McCaleb (2000-03-08). "Gore, Bush post impressive Super Tuesday victories". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Freedman, Samuel G. (2000-03-10). "Thanks, but no thanks". Politics2000. Salon.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Robinson, B.A. (2000-03-09). "Religion and the U.S. Primaries in the Year 2000". Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ a b Ian Christopher McCaleb (2000-03-09). "Bradley, McCain bow out of party races". CNN.com. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ a b Gamerman, Ellen (2000-03-10). "McCain halts campaign, but not fight for reform; In 'suspending' bid, he leaves race to Bush, keeps message alive". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ a b Hulse, Carl (2008-11-08). "The Return of John McCain, but Which One?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ a b Alison Mitchell (2000-03-20). "McCain Returns to an Uneasy Senate". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ Morgan Strong (2000-06-04). "Senator John McCain talks about the challenges of fatherhood". Dadmag.com. Archived from the original on 2001-04-17. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ Alexander, Paul (2001-09-27). "The Rolling Stone Interview: John McCain". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2008-05-19.[dead link]

- ^ Thomas, Evan (2009). A Long Time Coming: The Inspiring, Combative 2008 Campaign and the Historic Election of Barack Obama. New York City: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-607-5. p. 82.

- ^ Frank Bruni (2000-05-10). "McCain Backs Former Rival, Uniting G.O.P." The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b Borger, Julian (2000-05-10). "Reluctant McCain endorses Bush". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ^ Peter Marks (2000-05-14). "A Ringing Endorsement for Bush". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b James Bennet (2000-07-31). "Tears, Cheers and Jeers as McCain Delivers His Delegates to Bush". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ Richard L. Berke (2000-08-02). "For Republicans, a Night to Bolster Bush". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b Lawrence K. Altman (2008-03-09). "On the Campaign Trail, Few Mentions of McCain's Bout With Melanoma". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, pp. 329–32.

- ^ Drew, Citizen McCain, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Elisabeth Bumiller (2008-05-09). "McCain's Vote in 2000 Is Revived in a Ruckus". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, p. 332.

- ^ Peter Marks (2000-11-13). "Talk Turns Murky as Selection of President Lurches Into Uncharted Areas". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ Drew, Citizen McCain, p. 5.

- ^ Dubose, Lou; Jan Reid; Carl M. Cannon (2003). Boy Genius: Karl Rove, the Brains Behind the Remarkable Political Triumph. Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-192-4. p. 142.

- ^ "Who is Bush's Brain? Karl Rove is, according to a New Book Chronicling the Political Life of the Machiavelli Behind the Throne of King George". Buzzflash.com. 2003-06-02. Archived from the original on 2007-11-13. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Jim Davenport (2008-01-04). "S.C. has legacy of dirty tricks". The State. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ Byron York (2004-04-19). "The Democratic Myth Machine: About John McCain and Max Cleland, those (alleged) political martyrs". National Review. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ Richard H. Davis (2004-03-21). "The anatomy of a smear campaign". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Byron York (2008-01-20). "In South Carolina, McCain Finally Gets the Home-Field Advantage". National Review Online. Archived from the original on 2008-01-21. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin; Jonathan Weisman (2008-01-20). "This Time, McCain Defused Conservative Attacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ "McCain Campaign Assails Mailer In S.C." CBS News. Associated Press. 2008-01-15. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ a b Michael Cooper; Megan Thee (2008-01-20). "McCain Has Big Win in South Carolina; Huckabee Falls Short". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b "US President - R Primaries 2000". Our Campaigns. 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2007-12-27.