Contents

The Middlesex Canal was a 27-mile (44-kilometer) barge canal connecting the Merrimack River with the port of Boston. When operational it was 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and 3 feet (0.9 m) deep, with 20 locks, each 80 feet (24 m) long and between 10 and 11 feet (3.0 and 3.4 m) wide. It also had eight aqueducts.

Built from 1793 to 1803, the canal was one of the first civil engineering projects of its type in the United States, and was studied by engineers working on other major canal projects such as the Erie Canal. A number of innovations made the canal possible, including hydraulic cement, which was used to mortar its locks, and an ingenious floating towpath to span the Concord River. The canal operated until 1851, when more efficient means of transportation of bulk goods, largely railroads, meant it was no longer competitive.

In 1967, the canal was designated a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers. Remnants of the canal still survive and were the subject of a 1972 listing on the National Register of Historic Places, while the entire route, including parts that have been overbuilt, is the subject of a second listing in 2009.

History

Conception

By 1790, England had thirty years and all of continental Europe's many canals to draw on for the experience. In the years after the American Revolutionary War, the young United States began a period of economic expansion away from the coast. American men of influence had always kept an eye on news from Europe, especially from Great Britain, so when in the years from 1790–1794 the British Parliament passed eighty-one canal and navigation acts,[2] American leaders were paying attention.[2]

Because of extremely poor roads, the cost of bringing goods such as lumber, ashes, grain, and fur to the coast could be quite high if water transport was unavailable. Most American rivers were made unnavigable by rapids and waterfalls. Up and down the Atlantic coast, companies were formed to build canals as cheaper ways to move goods between the interior of the country and the coast. Well aware that to stay independent the nation needed to grow strong and develop industries, the news from Europe rekindled a number of previously dropped canal or navigations projects and began discussions leading in the next decades to many others.[2] The year 1790 is credited as the start of the American Canal Age.[3]

In Massachusetts, several ideas were proposed for bringing goods to the principal port, Boston, and connecting to the interior.[4] For about three years there were plans to connect the upper reaches of the Connecticut River, above the falls at Enfield Connecticut, to Boston through a canal to the Charles.[4] Connecticut was believed to rise at similar elevations to the Merrimack River's, which could be reached by a string of streams, ponds, lakes, and manmade canals—if the canals were built.[4] In the first two years, rough surveys sought the best route up to the Connecticut Valley; but no route was obviously best, and nobody championed a specific one. A few true believers, but lesser socialites, needed a champion and pestered the Secretary of War, Henry Knox to ignite the project. After the collapse of stocks in early 1793 put paid to a scheme to join the Charles River with Connecticut,[a] championed by Henry Knox, a group of leading Massachusetts businessmen and politicians led by States Attorney General James Sullivan proposed a connection from the Merrimack River to Boston Harbor in 1793. This became the Middlesex (County) Canal system.

The Middlesex Canal Corporation was chartered on June 22, 1793, with a signature by Governor John Hancock, who purchased shares with other political figures including John Adams, John Quincy Adams, James Sullivan, and Christopher Gore. The incorporators were James Sullivan; Oliver Prescott; James Winthrop; Loammi Baldwin; Benjamin Hall; Jonathan Porter; Andrew Hall; Ebenezer Hall; Samuel Tufts, Jr.; Willis Hall; Samuel Swan, Jr.; and Ebenezer Hall, Jr.[5] Sullivan was made the company's president; its vice president and eventually chief engineer was Loammi Baldwin, a native of Woburn, who had attended science lectures at Harvard College and was a friend of physicist Benjamin Thompson.[b]

Construction

The route of the canal was first surveyed in August 1793. Local lore is that it is on this expedition that Baldwin was introduced to a particular apple variety that now bears his name. The route survey, however, was sufficiently uncertain that a second survey was made in October. Due to discrepancies in their results, Baldwin was authorized by the proprietors to travel to Philadelphia in an effort to secure the services of William Weston, a British engineer working on several canal and turnpike projects in Pennsylvania under contract to the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company.[6][7] Baldwin's application to the Navigation company was successful: Weston was authorized to travel to Massachusetts. In July and August 1794, Weston, accompanied by Baldwin and several of the latter's sons surveyed and identified two possible routes for the proposed canal.[8] The proprietors then secured contracts to acquire the land for the canal, some of which was donated by its owners; in sixteen cases the proprietors used eminent domain proceedings to take the land.[9]

The basic plan was for the canal's principal water source to be the Concord River at its highest point in North Billerica, with additional water to be drawn as needed from Horn Pond in Woburn. The site where the canal met the Concord River had been the site of a grist mill since the 17th century, which the proprietors purchased along with all of its water rights. From this point, the canal descended six miles to the Merrimack River in East Chelmsford (now western Lowell) and 22 miles to the Charles River in Charlestown.

In late September 1794 ground was broken in North Billerica. Work on the canal was performed by a number of contractors. In some instances, local workers were contracted to dig sections, while in other areas contract labor was brought in from Massachusetts and New Hampshire for the construction work. A variety of engineering challenges were overcome, leading to innovations in construction materials and equipment. A form of hydraulic cement (made in part from volcanic materials imported at great expense from Sint Eustatius in the West Indies) was used to make the stone locks watertight. Because of its cost and the cost of working in stone, a number of the locks were made of wood instead. An innovation was made in earth-moving equipment with the development of a precursor of the dump truck, where one side of the carrier was hinged to allow the rapid dumping of material at the desired location.

Water was diverted into the canal in December 1800, and by 1803 the canal was filled to Charlestown. The first boat operated on part of the canal on April 22, 1802.

Merrimack canals

A variety of enterprises by all or a few of "the proprietors of the Middlesex Canal"[c] which were the corporations' principal stockholders and the board came together with other third parties or acted in a few cases as a combined whole to fund the development of other stretches of the canal up the Merrimack above Chelmsford.[10] By the completion of construction between Medford and Chelmsford, several extensions envisioned all along were also nearing completion. The whole system was complete in 1814,[10] and with just a few exceptions, overall came to operate with prices and regulations as set by the proprietors of the (main) Middlesex Canal. The following extensions opened up the balance of the Merrimack River to the New Hampshire capital, Concord, which acted as a staging point for riverine traffic deep into the river system penetrating the White and Green Mountains of New Hampshire and Vermont respectively.

| The Merrimack River Canals (Chapter IX title)[11] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjunct name | Year completed |

Length | Locks |

| Wicasee Canal | 1813 | short | one |

| Cromwell's Canal | 1813 | short | one |

| Union Locks and Canals | 1808 | nine miles | seven |

| Amoskeag's Canal (formerly Blodget's Canal) |

1807 | short | four to seven at various times |

| Hookset Canal | 1813 | 6.25 miles | three |

| The Bow Canal (Garven's Falls) |

1813 | 0.75 miles | four |

Operation

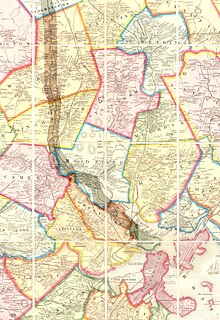

By 1808 the completed canal had reached Merrimack, New Hampshire, from the Charles (the downstream terminus) and was carrying two-thirds of the down freight and one-third of the up freight to Western New Hampshire and Eastern Vermont.[12] The other direction, the canal ran from 'Middlesex Village' or East Chelmsford, Massachusetts (The Town of Chelmsford was later divided and East Chelmsford was renamed Lowell, Massachusetts, now the fourth most populous city in Massachusetts, primarily because of the Lowell textile industry spawned by the transportation infrastructure and water power along the Middlesex Canal and the Nashua and Merrimack Rivers), through several sparser settled Middlesex County outlier suburbs such as Billerica, and Tewksbury, then closer-in suburban towns with the lower course running towards Boston generally along water courses nearly paralleling the routes of MA 38 from Wilmington, thence in Woburn along the Aberjona River from Horn Pond through Winchester (or Waterfield) into the Mystic Lakes and down the Mystic River between Arlington and Somerville on the west bank and Medford along the east (left) bank, until the river and canal ran into the Boston Harbor tidewater in the Charlestown basin.

At first, it terminated in Medford, but was later extended to Charlestown, Massachusetts, with a branch near Medford Center to the Mystic River.[13] Over time, the canal was connected to by a series of other canal companies, and many of those were owned in part by the canal proprietors,[10] which constructed spurs up through New Hampshire upstream along the Nashua and Merrimack Rivers, enabling freight to be transported as far inland as Concord, New Hampshire. Within two years of commencing operations, regular boat traffic operated by independent companies was reaching upriver over 50 miles (80 km).[10] Three main companies operated on the canal system. The water source for the canal was the Concord River at North Billerica. This was also the highest point of the canal and is the present location of the Middlesex Canal Association's museum.

Freight boats required 18 hours from Boston up to Lowell, and 12 hours down, thus averaging 2.5 miles per hour; passenger boats were faster, at 12 and 8 hours, respectively (4 miles per hour). As seen on later American canals, use was not restricted to freight and transit: people from the city would ride passenger boats on daylong tourism excursions to the countryside and take vacations in luxuriously fitted out canal boats, whole families spending a week or two lazing along the waterways in the heat of summer.

Freight statistics compiled for twenty years cited in the Harvard Economic study by Roberts[14] indicate the downriver trips from Concord to Boston took four days, and the reverse trip upriver took on average five days.[14] A round trip between Boston and Concord, New Hampshire usually took 7–10 days.[14] These speed limits were set and maintained by the board of proprietors to prevent wakes from damaging the canal sides. Roberts noted they were unlikely to be enforced, and generation of a shore damaging wake would require sails or animals to drive a canal boat in excess of 7 miles per hour (11 km/h), which would require dangerously stiff breezes in the correct direction.

The canal was one of the main thoroughfares in eastern New England until a few decades after the advent of the railroad. The Boston and Lowell Railroad (now a part of the MBTA Commuter Rail system) was built using the plans from the original surveys for the canal. Portions of the line follow the canal route closely, and the canal was used to transport construction materials and also an engine for the railroad.

The canal was no longer economically viable after the introduction of railroad competition, and the company collected its last tolls in 1851. The Middlesex Turnpike, incorporated in 1805, also contributed to its downfall. Investors who held their shares in the company lost money: shareholders invested a total of $740 per share but only reaped $559.50 in dividends. Those who sold their shares at an appropriate time made money: shares valued at $25 in 1794 reached a value of $500 in 1804 and were worth $300 in 1816.[15]

Before the corporation was dissolved, the proprietors proposed to convert the canal into an aqueduct to bring drinking water to Boston, but this effort was unsuccessful. After the canal ceased operation its infrastructure quickly fell into disrepair. In 1852 the company ordered dilapidated bridges over the canal torn down and the canal underneath filled in. Permission was given for the company to liquidate and pay the proceeds to the stockholders, and its 1793 charter was revoked in 1860. The company's records were given over to the state for preservation.[16] The canal corporation's land and dam in North Billerica, as well as the water rights on the Concord River, were sold to Charles and Thomas Talbot, who erected the Talbot Mills complex that now stands in the Billerica Mills Historic District.

Parts of the canal bed were covered by roads in the 20th century, including parts of the Mystic Valley Parkway in Medford and Winchester, and parts of Boston Avenue in Somerville and Medford. Boston Avenue crosses the Mystic River where the canal did. Parts of the canal in eastern Somerville were filled in by leveling Ploughed Hill in the late 19th century. Ploughed Hill was the site of notorious anti-Catholic riots in 1832 and had subsequently been abandoned.

Impact

The opening of the canal diminished the commercial viability of the port of Newburyport, Massachusetts, the outlet of the Merrimack River, since all trade from the Merrimack Valley in New Hampshire now went via the canal to Boston, rather than through the sometimes difficult to navigate river.[17]

The canal also played a prominent role in the eventual growth of Lowell as a major industrial center. Its opening brought on a decline in business at the Pawtucket Canal, a transit canal opened in the 1790s which bypassed the Pawtucket Falls just downstream from the Middlesex Canal's northern end. Its owners converted the Pawtucket Canal for use as a power provider, leading to the growth of the mill businesses on its banks beginning in the 1820s. The Middlesex Canal was used for the transport of raw materials, finished goods, and personnel to and from Lowell.

The canal's use of the Concord River had significant long-term environmental consequences. The raising of the dam height at North Billerica was believed to cause flooding of seasonal hay meadows upstream and prompted numerous lawsuits against the canal proprietors. These were all ultimately unsuccessful, due in part to the uncertainty of the science, and also in part to the political power of the proprietors. As the canal was in decline in its later years, the state legislature finally ordered the dam height to be lowered, but then repealed the order before it was executed. Analysis done in the 20th century suggests that the dam, which still stands (although no longer at its greatest height), probably had a flooding effect on hay meadows as far as 25 miles up the watershed. Many of these meadows had to be abandoned, and some now form portions of the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge; they are classified as wetlands.

The canal featured a number of innovations and was referred to as an example for later engineering projects. The use of hydraulic cement to mortar the locks is the first known use of the material in North America. The route was surveyed using a Wye level (an early version of a dumpy level), again the first recorded use in America. At North Billerica, where the canal met the Concord River at the millpond, a floating towpath was devised to handle the needs of crossing traffic patterns.[18]

Today

Though significant portions of the Middlesex Canal are still visible, urban and suburban sprawl is quickly overcoming many of the remains. The Middlesex Canal Association,[19] founded in 1962, has erected markers along portions of the canal's path. Prominent portions of the canal that are still visible include water-filled portions in Wilmington, Billerica, and near the Baldwin House in Woburn. Dry walkable sections can be found in Winchester, most notably a section at the Mystic Lakes where an aqueduct was situated, and Wilmington, where aqueduct remnants are also visible in the town park off Route 38. Most of the canal south of Winchester has been overbuilt by roads and residential construction, although traces may still be discerned in a few places.

In 1967 the canal was designated a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark (one of the first such designations made) by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The surviving elements of the canal are the subject of a 1972 listing on the National Register of Historic Places, while the entire route, including parts that have been overbuilt, is the subject of a second listing in 2009.

The Middlesex Canal Association maintains a museum in North Billerica, Massachusetts, at the Faulkner Mills. Directions and additional information are available on the Middlesex Canal Association website.[19]

Gallery

-

A segment of the canal in Wilmington

-

An overgrown dried-out remnant of the canal in Chelmsford

-

A walkable section of the canal in Winchester

-

Foundation remnants lining the Mystic River in Somerville and Medford

-

Plaque describing the canal in Medford, Massachusetts

-

Middlesex Canal Plaque

Notes

- ^ If indeed, there was any real interest in the speculation by Secretary Henry Knox, the economic downturn imperiled family holdings curtailing speculations with the family fortune.[4] Roberts cites multiple letters by Boston cognizatti, most of which seem to have been totally ignored by Secretary Knox. No reply is recorded where he is effusive and engaged in the project after a few initial communications in 1790.[4]

- ^ Baldwin's sons would all go into civil engineering and the family became important figures in the building industrial revolution.[4]

- ^ "The proprietors of the Middlesex Canal" which were the corporation's stockholders, as titled in the enabling act of 1793.

References

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Chapters I, pp. 4-5

- ^ James E. Held (July 1, 1998). "The Canal Age". Archaeology (Online) (July 1, 1998). A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

Little is known of the vessels and waterways that fueled the Canal Age in the United States, from 1790 to 1855, since few records were kept and fewer of the much-used boats survived.

- ^ a b c d e f Roberts, Chapters I and Chapter II

- ^ "An Act incorporating James Sullivan, Esq. and others, by the Name and Style of The Proprietors of the Middlesex Canal", June 22, 1793, p. 465ff, in Private and Special Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts from the year 1780 etc. , 1, 1805.

- ^ Kirby, Richard Shelton. "William Weston and his contribution to early American engineering." Transactions of the Newcomen Society 16.1 (1935): 111-127.

- ^ Clarke, p. 25

- ^ Clarke, pp. 28-29

- ^ Clarke, p. 35

- ^ a b c d Roberts, Chapter IX, The Merrimack River Canals, pp. 124–135

- ^ Roberts, Christopher (1938). The Middlesex Canal 1793–1860. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, Harvard Economic Studies, Volume LXI, 386 R.

- ^ Roberts, pp. 125-126

- ^ a b Jay B. Griffen (May 2006). "The Incredible Ditch". Medford Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Chapter X - Boats and Freights in Inland Trade, p. 141 cite as a 20-year average, nine days for the round trip Concord-Boston.

- ^ Clarke, pp. 123-124

- ^ Clarke, pp. 127-130

- ^ Muir, Diana, Reflections in Bullough's Pond, University Press of New England, p.112

- ^ Clarke, p. 10

- ^ a b Middlesex Canal Association website

Sources

- Clarke, Mary Stetson (1974). The Old Middlesex Canal. Easton, PA: Center for Canal History and Technology. ISBN 0930973054.

- Roberts, Christopher (1938). The Middlesex Canal 1793–1860. Harvard Economic Studies, Volume LXI, 386 R. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- Hopkins, Arthur T. (January 1898). "The Old Middlesex Canal". The New England Magazine. Vol. 17, no. 5. pp. 518–532 – via HathiTrust. Other online archives of The New England Magazine.

- Massachusetts General Court. House of Representatives. Joint Special Committee on the Flowage of Meadows on Concord and Sudbury Rivers. January 28, 1860. (1860). Report of the Joint Special Committee upon the Subject of the Flowage of Meadows on Concord and Sudbury Rivers. Boston: William White. ISBN 9780962579486 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) This is how the Middlesex Canal Corporation was dissolved. - The Middlesex Canal Commission; In association with The North Middlesex Council of Governments and The Massachusetts Historical Commission (2008). Middlesex Canal National Register Historic District Assessor's Plan Map Book (PDF). Winchester, Mass.: The Waterford Design Group.

- Early Canal Transportation: The Boats of the Middlesex Canal: An Exhibit by Thomas Joy and Gretchen Sanders Joy. Patrick J. Mogan Cultural Center, University of Lowell Center for Lowell History. 1991. Archived from the original on August 12, 2002.

- Seaburg, Alan (2009). Life on the Middlesex Canal. Thomas Dahill (illustrations). Billerica, Mass.: The Anne Miniver Press. ISBN 9780972089678. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2011 – via Google Books.

- Seaburg, Alan (2017). A Social History of the Middlesex Canal (PDF). Thomas Dahill (illustrations). Billerica, Mass.: The Anne Miniver Press.

- Seaburg, Carl; Seaburg, Alan; Dahill, Thomas (artwork) (1997). The Incredible Ditch: A Bicentennial History of the Middlesex Canal. Medford, Mass.: Anne Miniver Press for the Medford Historical Society. ISBN 9780962579486.