Contents

In Greek mythology, Silenus (/saɪˈliːnəs/; Ancient Greek: Σειληνός, romanized: Seilēnós, IPA: [seːlɛːnós]) was a companion and tutor to the wine god Dionysus. He is typically older than the satyrs of the Dionysian retinue (thiasos), and sometimes considerably older, in which case he may be referred to as a Papposilenus. Silen [1] and its plural sileni refer to the mythological figure as a type that is sometimes thought to be differentiated from a satyr by having the attributes of a horse rather than a goat, though usage of the two words is not consistent enough to permit a sharp distinction.[citation needed]

Silenus presides over other daimons and is related to musical creativity, prophetic ecstasy, drunken joy, drunken dances and gestures.[2]

In the decorative arts, a "silene" is a Silenus-like figure, often a "mask" (face) alone.

Evolution

The original Silenus resembled a folkloric man of the forest, with the ears of a horse and sometimes also the tail and legs of a horse.[3] The later sileni were drunken followers of Dionysus, usually bald and fat with thick lips and squat noses, and having the legs of a human. Later still, the plural "sileni" went out of use and the only references were to one individual named Silenus, the teacher and faithful companion of the wine-god Dionysus.[4]

| Coin from Mende depicting Silenus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Obv: Inebriated Silenus reclining on a donkey, holding kantharos with wine | Rev: Vine of four grape clusters within shallow linear incuse square, ΜΕΝΔΑΙΩΝ, of Mendians |

| Silver tetradrachm from Mende, 460–423 BC | |

A notorious consumer of wine, he was usually drunk and had to be supported by satyrs or carried by a donkey. Silenus was described as the oldest, wisest and most drunken of the followers of Dionysus, and was said in Orphic hymns to be the young god's tutor. This puts him in a company of phallic or half-animal tutors of the gods, a group that includes Priapus, Hermaphroditus, Cedalion and Chiron, but also includes Pallas, the tutor of Athena.[5]

When intoxicated, Silenus was said to possess special knowledge and the power of prophecy. The Phrygian King Midas was eager to learn from Silenus and caught the old man by lacing a fountain with wine from which Silenus often drank. As Silenus fell asleep, the king's servants seized and took him to their master. An alternative story was that when lost and wandering in Phrygia, Silenus was rescued by peasants and taken to Midas, who treated him kindly. In return for Midas' hospitality Silenus told him some tales and the king, enchanted by Silenus' fictions, entertained him for five days and nights.[6] Dionysus offered Midas a reward for his kindness toward Silenus, and Midas chose the power of turning everything he touched into gold. Another story was that Silenus had been captured by two shepherds, and regaled them with wondrous tales.

In Euripides's satyr play Cyclops, Silenus is stranded with the satyrs in Sicily, where they have been enslaved by the Cyclopes. They are the comic elements of the story, a parody of Homer's Odyssey IX. Silenus refers to the satyrs as his children during the play.

Silenus may have become a Latin term of abuse around 211 BC, when it is used in Plautus' Rudens to describe Labrax, a treacherous pimp or leno, as "...a pot-bellied old Silenus, bald head, beefy, bushy eyebrows, scowling, twister, god-forsaken criminal".[7] In his satire The Caesars, the emperor Julian has Silenus sitting next to the gods to offer up his comments on the various rulers under examination, including Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Augustus, Marcus Aurelius (whom he reveres as a fellow philosopher-king), and Constantine I.[8]

Silenus commonly figures in Roman bas-reliefs of the train of Dionysus, a subject for sarcophagi, embodying the transcendent promises of Dionysian cult.

- Silenus as member of the Dionysian entourage

-

Front side of a Roman sarcophagus, depicting the wedding of Dionysos and Ariadne, with old Silenus figuring in their entourage (sixth figure from the right), 150–160 CE (Glyptothek, Munich)

-

Papposilenus in a Dionysian procession, bell-krater from Paestum, Magna Graecia, c. 355 BC (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Satyr holding a thyrsus, supporting a drunken ivy-wreathed silenus, from the Borghese Vase, 1st century BC (Louvre)

-

Hermaphroditus and Silenus. On the right a maenad with thyrsus. Roman fresco from Pompeii, House of M. Epidi Sabini, IX.1.22.

-

Bacchus pours out wine for a panther, while Silenus plays the lyre, painting from Boscoreale, Campania, c. 30 BC (British Museum)

Papposilenus

Papposilenus is a representation of Silenus that emphasizes his old age, particularly as a stock character in satyr play or comedy. In vase painting, his hair is often white, and as in statuettes, Papposilenus has a pot belly, flabby breasts and shaggy thighs. In these depictions, it is often clear that the Papposilenus is an actor playing a part. His costuming includes a body stocking tufted with hair (mallōtos chitōn) that seems to have come into use in the mid-5th century BC.[9]

-

Papposilenus playing an aulos, bronze from 3rd century BC, (Walters Art Museum)

-

Two papposilenoi as singers at the Panathenaia on an Attic red-figure bell-krater attributed to Polion, c. 420 BC

Wisdom

A theme in Greek philosophy and literature is the wisdom of Silenus, which posits an antinatalist philosophy:

You, most blessed and happiest among humans, may well consider those blessed and happiest who have departed this life before you, and thus you may consider it unlawful, indeed blasphemous, to speak anything ill or false of them, since they now have been transformed into a better and more refined nature. This thought is indeed so old that the one who first uttered it is no longer known; it has been passed down to us from eternity, and hence doubtless it is true. Moreover, you know what is so often said and passes for a trite expression. What is that, he asked? He answered: It is best not to be born at all; and next to that, it is better to die than to live; and this is confirmed even by divine testimony. Pertinently to this they say that Midas, after hunting, asked his captive Silenus somewhat urgently, what was the most desirable thing among humankind. At first he could offer no response, and was obstinately silent. At length, when Midas would not stop plaguing him, he erupted with these words, though very unwillingly: 'you, seed of an evil genius and precarious offspring of hard fortune, whose life is but for a day, why do you compel me to tell you those things of which it is better you should remain ignorant? For he lives with the least worry who knows not his misfortune; but for humans, the best for them is not to be born at all, not to partake of nature's excellence; not to be is best, for both sexes. This should be our choice, if choice we have; and the next to this is, when we are born, to die as soon as we can.' It is plain therefore, that he declared the condition of the dead to be better than that of the living.

- – Aristotle, Eudemus (354 BCE), surviving fragment quoted in Plutarch, Moralia. Consolatio ad Apollonium, sec. xxvii (1st century CE) (S. H. transl.)

This passage is redolent of Theognis' Elegies (425–428). Silenus' wisdom appears in the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer, who endorsed this famous dictum. Via Schopenhauer, Nietzsche discusses the "wisdom of Silenus" in The Birth of Tragedy.

Both Socrates and Aesop were sometimes described as having a physical appearance like that of Silenus, with broad flat faces and fat bellies.[10]

- Drunken Silenus, from ancient to modern times

-

Drunk papposilenus supported by two young men, Etruscan red-figure stamnos from Vulci, c. 300 BC (Louvre)

-

Silenus detail from a Roman-era marble sarcophagus, 2nd century AD (Antalya Museum)

Classical tradition

In art

In the Renaissance, a court dwarf posed for the Silenus-like figure astride a tortoise at the entrance to the Boboli Gardens, Florence. Rubens painted The Drunken Silenus (1616–17), now conserved in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich – the subject was also treated by van Dyck and Ribera.

During the late 19th century in Germany and Vienna, symbolism from ancient Greece was reinterpreted through a new Freudian prism. Around the same time Vienna Secession artist Gustav Klimt uses the irreverent, chubby-faced Silenus as a motif in several works to represent "buried instinctual forces".[11]

-

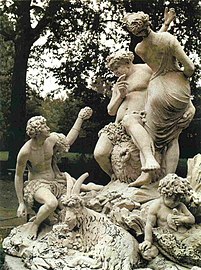

Jean-Baptiste Boudard: Group of the Silen, marble sculpture in the Ducal Park, Parma, 1766

-

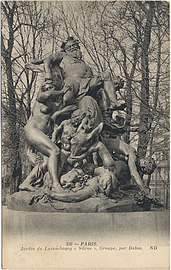

Jules Dalou: Triomphe de Silène, bronze sculpture, Jardin du Luxembourg, Paris, 1897

-

Rupert Bunny: Silenus with Some Perfect Ladies of Phrygia Gave a Cocktail Party, c. 1938

In literature

In Gargantua and Pantagruel, Rabelais referred to Silenus as the foster father of Bacchus. In 1884 Thomas Woolner published a long narrative poem about Silenus. In Oscar Wilde's 1890 novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry Wooton turns praise of folly into a philosophy which mocks "slow Silenus" for being sober. In Brian Hooker's 1923 English translation of Edmond Rostand's Cyrano de Bergerac, Cyrano disparagingly refers to the ham actor Montfleury as "That Silenus who cannot hold his belly in his arms."

Professor Silenus is a character in Evelyn Waugh's first novel, Decline and Fall. He features as the disaffected architect of King's Thursday and provides the novel with one of its primary motifs. In the prophetic style of the traditional Greek Silenus he informs the protagonist that life is

a great disc of polished wood that revolves quickly. At first you sit down and watch the others. They are all trying to sit in the wheel, and they keep getting flung off, and that makes them laugh, and you laugh too. It's great fun... Of course at the very centre there's a point completely at rest, if one could only find it.... Lots of people just enjoy scrambling on and being whisked off and scrambling on again.... But the whole point about the wheel is that you needn't get on it at all.... People get hold of ideas about life, and that makes them think they've got to join in the game, even if they don't enjoy it. It doesn't suit everyone...[12]

Silenus is one of the two main characters in Tony Harrison's 1990 satyr play The Trackers of Oxyrhynchus, partly based on Sophocles' play Ichneutae (5th century BC).

Scientific nomenclature

Carl Linnaeus used the feminine form Silene as the name of a genus of flowering plant.[13]

Gallery

-

Statue of Silerius. Exhibition in Taipei 2013

-

Statue of Silenus, detail

-

Gold phaler (ornament worn by horses) representing Silenus, Syria, 3rd century BC

-

Mask of Silen, first half of 1st century BC

-

Two Roman bronze fulcra (couch ornaments) representing Silenus, 1st century BC – 1st century AD (Art Institute of Chicago)

-

Mosaic with mask of Silenus

-

Statue of Silenus, 2nd century BC (Archaeological Museum of Delos)

-

Statue of Silenus, Archaeological Museum of Delos, detail

Footnotes

- ^ van Hoorn, G. (November 1954). "Choes and Anthesteria". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 74 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Georgieff, D. 2017. The essence of the Dionysian mysteries. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.36183.06568

- ^ Entry "Satyrs and silens", in: The Oxford Classical Dictionary

- ^ Kerenyi, p. 177.

- ^ Kerenyi, p. 177.

- ^ J. Thompson (2010). "Emotional Intelligence/Imaginal Intelligence", in: Mythopoetry Scholar Journal 1.

- ^ Plautus

- ^ The Caesars on-line English translation.

- ^ Albin Lesky, A History of Greek Literature, translated by Cornelis de Heer and James Willis (Hackett, 1996, originally published 1957 in German), p. 226; Guy Hedreen, "Myths of Ritual in Athenian Vase-Paintings of Silens", in: The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond: From Ritual to Drama (Cambridge University Press, 2007), p. 151.

- ^ Ulrike Egelhauf-Gaiser, "The Gleaming Pate of the Pastophoros: Masquerade or Embodied Lifestyle?", in: Aspects of Apuleius' Golden Ass, III (Brill, 2012), p. 59, citing passages in Plato and Xenophon.

- ^ Carl Schorske Fin-de-Siècle Vienna – Politics and Culture, 1980, page 221

- ^ Michael Gorra (Summer, 1988). "Through Comedy toward Catholicism: A Reading of Evelyn Waugh's Early Novels". Contemporary Literature 29 (2): 201–220.

- ^ Umberto Quattrocchi, CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names, 1999, ISBN 0-8493-2678-8, 4:2482

Further reading

- Guy Michael Hedreen, 1992. Silens in Attic Black-figure Vase-painting: Myth and Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan) Catalogue of the corpus.

- Karl Kerenyi. The Gods of the Greeks, 1951.

- Over 300 images of Silenus at the Warburg Institute's Iconographic Database Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.