Contents

Starlight Park is a public park located along the Bronx River in the Bronx in New York City. Starlight Park stands on the site of an amusement park of the same name that operated in the first half of the 20th century.[1][2]

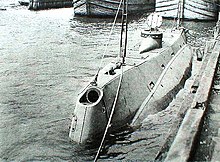

The amusement park was originally built for the Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries, which was hosted in 1918, and as such the park was known as Exposition Park during that time. During its heyday, Starlight Park featured various amusement rides, as well as the Bronx Coliseum and the submarine USS Holland. Much of the park was destroyed in a 1932 fire, though the remaining attractions continued to operate until 1946.

The northeastern part of the amusement park became the West Farms Depot of MTA Regional Bus Operations. A city park, operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, was built in the late 1950s as part of the construction of the Sheridan Expressway. The highway was built parallel to the Bronx River on the former site of the amusement park.

History

Amusement park

Early years

The site had originally contained the estate of politician William Waldorf Astor.[3][4][5] Exposition Park was initially leased in 1914[5] as part of the plans for the Bronx International Exposition of Science, Arts and Industries,[6] which opened in 1918.[4] The exposition, intended to showcase the recent creation of Bronx County, was so unsuccessful that it only attracted one country, Brazil.[7]: 149 The park was renamed Starlight Park on October 18, 1919, shortly after the exposition's close.[8][1] The Bronx Expositions Corporation purchased numerous rides and attractions, and converted the "exhibition hall" to an ice rink and dance hall.[8]

The rebranded Starlight Park opened in 1920. Throughout that year Starlight Park's operators added several attractions and concessions, including shooting galleries, games of chance, and a dark ride through an exhibit of "grottos and other worldly sights".[8] The park continued to add attractions and events for the 1921 season, including a baseball field, several shows, and a kid's club.[9] Further additions in 1922 included a sound system by the pool area; a program of movies broadcast from a projector; and rides such as electric riding cars, the Gyroplane, and the Maelstrom. Numerous promotional events were also held that year, including a Film Players Club fundraiser, a singing contest, and a "Surprise Week" featuring a different performance each day of the week.[10]

Lawsuit and incidents

In December 1920 the Bronx Expositions Corporation was the subject of a breach of contract lawsuit filed by Exposition Catering,[11] which at the time was one of the largest lawsuits filed in the entertainment industry.[8] According to the lawsuit, the Expositions Corporation had failed to uphold a contract to build an elaborate entrance, a convention center, and a permanent exposition, and had instead erected "a cheap amusement park" because of their mismanagement of money.[9][11] The outcome of the lawsuit was unknown.[9] During this time, several other lawsuits were filed against the park because of numerous incidents which resulted in injuries.[9]

In 1922, there were two accidents that damaged the park's reputation.[12] On May 21, a rider decided to stand up on the roller coaster as it rounded a curve, fell off, and was killed. The operator applied the emergency brake, injuring six other riders.[12][13] That November, Starlight Park's large Exposition Hall was destroyed in a fire, and the park's Ferris wheel and scenic railway were also badly damaged. Two smaller dance halls replaced the Exposition Hall.[12] Furthermore, the park in general was susceptible to fire because most of the buildings were flammable wooden structures. A thunderstorm on June 23, 1922, burned down several structures.[12][14]

There were several other incidents that brought negative attention to Starlight Park. For instance, throughout the park's operation, there were numerous drownings in the pool area.[12] Additionally, over two hundred bathers' items were stolen during a mass robbery in 1925.[12][15] The following year, a boxer died in a match at Starlight Park.[16] A circus performer died in 1930 after falling 40 feet (12 m) from a high wire.[17]

Later years and closure

The park was at its largest in 1926 when it had 150 concessions and 26 rides.[18] The following year saw the installation of the Forest Inn, a combined restaurant/performance venue. Many of the original attractions still remained, including the Bug House, Nonsense House, the Whip, a Noah's Ark, a Skee-Ball game, the wooden coaster, the Ferris wheel, the Frolic, the Motor Dome, the Whirlpool, Witching Waves, and the Canals of Venice.[19] In 1929, the 15,000-seat Bronx Coliseum opened at Starlight Park, becoming the park's new sporting arena.[20][21] With the start of the Great Depression in 1929, Starlight Park's operators installed several rides, as well as launched promotions such as free-admission days and contests, in an attempt to increase its visitor count. The park increased its schedule of events, as they were seen as more efficient than adding new rides.[17]

On August 8, 1932, a large section of Starlight Park was destroyed in a fire that started under the now-abandoned roller coaster and spread to numerous concessions. Fifteen thousand guests saw the fire, which was said to be started by several young boys.[17][22][23] In the aftermath of the fire, the Coliseum was the largest remaining attraction and continued to keep the park profitable. Several political rallies, including those of the Communist Party USA, were held at the Coliseum. However, Starlight Park also continued to make a profit from the swimming pool, picnic areas, and sporting fields.[17] Furthermore, in 1933, Starlight Park's manager added several recreational facilities in order to keep the park solvent. By this time, it was no longer envisioned as an amusement park.[17]

By 1940, Starlight Park was bankrupt, and a portion of the park and Coliseum were sold at auction.[17][24] The new owner, Richard F. Mount, leased the structures to a syndicate in May 1941, which in turn proposed building new sporting fields on the site.[17] However, these plans were abridged by World War II and the United States Army took over the Coliseum between 1942 and 1946.[7]: 152 [25] The stucco and wood bathing pavilion was damaged in a fire in July 1946[26][27] and was totally destroyed by another blaze the next year.[28] The park site was condemned,[27] and the Coliseum became the West Farms bus depot, operated by MTA Regional Bus Operations.[7]: 152 [25]

Conversion to city park

A city park, operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, was built in the late 1950s as part of the construction of the Sheridan Expressway. The highway was built parallel to the Bronx River on the former site of Starlight Park, which had been condemned to provide the right-of-way for both the Sheridan and Cross Bronx Expressways. As part of the project, a city park with the same name was created in its place, east of the expressway.[29][30][31] The city park comprised land west and south of the original site of the amusement park, along both banks of the river.[7]: 152

In the 1990s, after Youth Ministries had made the state aware of pollution on the Bronx River, the New York state government started to clean up the river. Cleanup efforts were delayed when chemicals from an old gas plant at the site were discovered in 2003. As part of the plan to clean up the pollution, the New York State Department of Transportation agreed to rebuild the park and connect it to the Bronx River Greenway, a proposed waterfront path along the Bronx River.[32] In 2013, after a 10-year renovation that cost $18 million, NYC Parks reopened a 13-acre (5.3 ha) section of the public park.[33][34] Another 11-acre (4.5 ha) segment remained closed because of a disagreement with Amtrak, who owned the Northeast Corridor railroad tracks on the park's eastern edge.[32] A $13 million environmentally-friendly headquarters for the Bronx River Alliance, described in The New York Times as "the greenest building in the South Bronx", opened within the park in 2016.[35]

In 2017, an expansion of the new Starlight Park was announced. As part of this expansion, parts of the park would undergo environmental cleanups. The Phase 2 project would also connect Starlight Park to Concrete Plant Park south of Westchester Avenue via new bridges across the Bronx River and the Northeast Corridor.[33] This coincided with another plan to downgrade Sheridan Expressway to a street-level boulevard so that the surrounding community could more easily access Starlight Park.[36] At the time, the park was only accessible via the East 174th Street bridge that crosses both the expressway and the Bronx River. The project was undertaken to improve pedestrian safety and increase access to both Starlight Park and the Bronx River shoreline.[37][38] The project to downgrade the Sheridan Expressway began in late 2018[39][40] and was completed in December 2019.[41] Contractors renovated the park during the early 2020s.[42] Following a $41 million renovation, NYC Parks opened an 2.7-acre (11,000 m2) section of the park in April 2023.[43][44]

Current attractions

Current recreational facilities in Starlight Park include four baseball fields (two made of grass and two of asphalt), as well as five checkers tables and eight handball courts.[29] A soccer field overlaps with two of the baseball fields, and a basketball court and playground are located south of the 174th Street bridge over the park.[45] A seasonal canoe launch is located in the park as well.[46] During the summer, the Bronx River Alliance operates a canoeing program called Community Paddle; the program charges a fee on Saturdays but is free on Fridays.[42] Plans for the park, announced in 2017, call for a waterfront greenway, as well as the opening of the parkland on the eastern bank of the Bronx River.[33]

Former attractions

Rides

Starlight Park amusement park featured fireworks displays, a roller coaster, a swimming pool, and carnival games of skill and chance.[6] The initial attractions were built for the Bronx International Exposition. The swimming pool was marketed as the world's largest saltwater pool, measuring 300 by 350 feet (91 by 107 m) with a capacity of 2,500,000 U.S. gallons (9,500,000 L), and ranging from 0 to 10 feet (0.0 to 3.0 m) deep. The pool contained diving boards and a wave pool machine at the deep end, as well as a 50-by-55-foot (15 by 17 m) beach with sand brought from Rockaway, Queens.[47]: 536 [48] The fair also contained a scenic ridable miniature railway on the Bronx River, a "mountain" exhibit with a 65-foot-tall (20 m) waterfall, and a hotel nearby.[47]: 536–537 LaMarcus Adna Thompson built a wooden roller coaster at the site,[48] which featured a dual track.[49] The Eli Bridge Company's Ferris wheel from the Panama–California Exposition was brought over to the Bronx World's Fair.[48] Other attractions included a bathing pavilion that could fit 4,500 people; a convention center; and 15 large pavilions, including Chinese and North Sea-themed pavilions, as well as those for fine arts, liberal arts, and American achievements.[48][50]

At the end of the 1918 Exposition, the "exhibition hall" became an ice rink and dance hall.[7]: 150 When the Exposition Hall was burned down in 1922, it was replaced with two smaller dance halls.[12] By 1927, the park had installed Witching Waves, an undulating flat ride.[19] A Tilt-A-Whirl, a scooter ride, a new Noah's Ark and a "Snap o' the Whip" ride were added in 1929 to draw patrons.[17] Additions in 1931 included a miniature golf course on the site of Witching Waves, as well as a roller rink.[18]

Other attractions

One of the park's most popular attractions was the submarine Holland. After being constructed by Irish-American inventor John Philip Holland in 1888, the Holland became the first submarine commissioned by the United States Navy. She had been maintained by the navy at Norfolk, Virginia, for training purposes until 1914, when she became a museum ship in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, New Jersey. The submarine then moved to Starlight Park in 1918 and remained there until 1932, when she was disassembled for scrap as part of the entire park's demolition.[6]

The 15,000-seat Bronx Coliseum was also located in Starlight Park, and was opened in 1929.[20][21] It was the home field of the New York Giants soccer team, but also featured numerous other sporting events as well as circuses.[51] The Coliseum also held events when Madison Square Garden in Manhattan was already hosting another event. The stadium was originally built for the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was transported to 177th Street and Devoe Avenue in 1928.[17] It came to be called the New York Coliseum, which had no relation to the building with the same name that was later built at Columbus Circle in Manhattan.[51]

Other structures

The amusement park was also home of the studios of radio station WBNX, which started broadcasting in 1926 and was known as "the official broadcasting station of the New York Coliseum".[52] It was located at Starlight Park until 1932, when the park's partial closure forced the station to relocate.[19][53]

Events

The first summer music festival in Starlight Park was hosted in 1921 when the Russian Symphony Orchestra Society performed Wagner at the park.[19][54] Starting in 1926, the park offered free 14-week-long programs of opera music in the summer, in an attempt to give the masses access to high culture at no cost.[51] The first of these operas, Rigoletto, was performed in May 1926.[19][55] The shows were given in the open air until the Starlight Park Stadium was erected, after which performances were moved to the stadium.[51] On Saturday nights, big-band jazz played for dancers on an outdoor dance floor, giving the park a feeling of "blue collar country club".[56]

Semiprofessional sports teams would compete at Starlight Park's baseball field, added in 1921.[9] Events such as baseball and soccer games, boxing matches, horseshoe throwing, and track and field competitions also drew crowds to Starlight Park.[19] One such match in October 1926 resulted in the death of boxer Joseph Geraghty; his opponent was later cleared of any wrongdoing.[16] After the Coliseum opened in 1929, these events were moved to the stadium.[17]

Children were also able to join a club called the Kiddie Klub, which entitled the member to several designated free-admission days at numerous amusement parks in New York City. Prospective members had to clip three coupons from different newspapers in exchange for a membership pin.[49] The first Kiddie Klub day on July 13, 1921, saw over 20,000 children.[49][57] The following year, there was a miscommunication about the Kiddie Klub event. On July 12, 1922, the Kiddie Klub free day had been held at Coney Island's Luna Park, but about 50 children showed up at Starlight Park instead.[10] The actual Kiddie Klub day at Starlight Park was held two weeks later.[10][58]

Vaudeville acts and high diving performances were other popular events hosted in Starlight Park.[9] Toward the late 1920s, in the park's attempt to bring back patrons, more tawdry shows began performing at Starlight Park.[18]

See also

References

- ^ a b Futrell, Jim (2006). Amusement Parks of New York. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-811-73262-8. Retrieved December 30, 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ultan, Lloyd ; Unger, Barbara (2000). Bronx Accent – A Literary and Pictorial History of the Borough. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-813-52863-2. Retrieved December 30, 2012 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Bronx World's Fair of 1918: the failure which became a magical park". The Bowery Boys: New York City History. September 13, 2016. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "Crowds See Opening Of Trade Exposition; Police Commissioner Enright Receives Keys for City at Formal Opening. Permanent Show Planned; Borough President Bruckner Thanks Promoters for Choosing Site in the Bronx". The New York Times. June 30, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 92.

- ^ a b c McNamara, John (1984). History in Asphalt – The Origin of Bronx Street and Place Names, Borough of the Bronx, New York City. The Bronx, New York: Bronx County Historical Society. pp. 287, 314, 397–398. ISBN 978-0-941-98016-6. Retrieved December 30, 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e DeVillo, S.P. (2015). The Bronx River in History & Folklore. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-62585-490-2. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e f Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 98.

- ^ a b "ASKS $5,000,000 DAMAGES.; Bronx Catering Company Sues Exposition for Contract Breach". The New York Times. December 15, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 99.

- ^ "Two Killed, One Hurt in Automobile Crash; Six Are Injured in Roller Coaster Mishap". The New York Times. May 21, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "TEN MINUTE CYCLONE KILLS 4, RAZES WALL, UPROOTS 500 TREES; Centres Fury on Brooklyn, Overturning Houses -- Damage Closes Prospect Park". The New York Times. June 27, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "2 SHOT IN HOLD-UP; 200 BATHERS ROBBED; Eight Armed Men Order Six Employes at Starlight Park, Bronx, to 'Stick 'Em Up.' LOOT CHECK ROOM AND FLEE Officer and Thief Wounded in Running Fight -- 500 Patrons in Panic. 2 SHOT IN HOLD-UP; 200 BATHERS ROBBED". The New York Times. August 13, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Boxer Cleared of Homicide Charge". The New York Times. October 6, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 103.

- ^ a b Dawson, James P. (April 7, 1929). "NEW BOXING ARENA WILL OPEN FRIDAY; Chocolate and Graham to Meet in Fifteen-Round Inaugural Feature in the Bronx. COLISEUM TO SEAT 18,500 Dominick Petrone and Al Goldberg Head Card Tomorrow Night at New Broadway, Brooklyn". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "FORECLOSURE FACES JEFFERSON SHRINE; S. G. Gibboney, Head of Memorial Association, Appeals for Funds to Save Monticello. ABOUT $127,000 IS NEEDED Dr. G. J. Ryan Urges Public to Aid in Preserving Birthplace of Great Leader". The New York Times. August 8, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "Boys Start Blaze in Starlight Park". New York Daily News. August 8, 1932. p. 75. Retrieved October 16, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Mortgagees Buy in Part Of Bronx Sports Center". The New York Times. August 3, 1940. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b Valentino, Elisa (July 12, 2018). "WEEKDAY MAGAZINE – Starlight Park: A Century of Bronx History – Part 2". This Is The Bronx. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ "Fire Damages Bronx Bathhouse". New York Evening World. July 18, 1946. p. 11. Retrieved October 16, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 106.

- ^ "2-Alarm Fire in Starlight Park". The New York Times. October 23, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ a b "Starlight Park: History". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Chapter 2: Greenway Route from South to North" (PDF). Bronx River Greenway Strategic Plan. Bronx River Alliance. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Photo Report on Progress of Cross Bronx Expressway" (PDF). New York Post. April 30, 1950. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b Wall, Patrick (May 13, 2013). "Starlight Park Officially Reopens, But Remains Disconnected to Greenway". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c Wirsing, Robert (May 12, 2017). "Starlight Park will undergo a major transformation as part of the $40 million Bronx River Greenway project". Bronx Times. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ "Starlight Park Opens With A Community Celebration, On Land And On Water". Starlight Park News. NYC Parks. May 10, 2013. Archived from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ Stapinski, Helene (July 10, 2016). "The Greenest Building in the South Bronx". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- ^ Sheridan Blvd Overall Plan. governor.ny.gov. New York State Department of Transportation. 2017. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (March 19, 2017). "Cuomo Plots Demise of Bronx's Unloved Sheridan Expressway". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ Durkin, Erin (March 19, 2017). "Cuomo announces Sheridan Expressway to be demolished in favor of pedestrian boulevard in the Bronx". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ Rivoli, Dan (September 19, 2018). "Feds pave way to transform the Bronx's Sheridan Expressway". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- ^ Walker, Ameena (September 20, 2018). "Bronx's Sheridan Expressway overhaul gets federal approval". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Barone, Vincent (December 11, 2019). "State finishes Sheridan Boulevard conversion to boost Bronx River waterfront access". www.amny.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Yensi, Amy (July 14, 2022). "Residents hope to preserve Starlight Park, an 'oasis in the Bronx'". Spectrum News NY1 New York City. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ Golata, Justine (May 1, 2023). "NYC Parks Unveils A $41 Million Greenspace In The Bronx". Secret NYC. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ "NYC Parks, NYC DDC, and Partners Officially Open $41 Million Major Greenspace Expansion in Starlight Park in the Bronx". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. April 28, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ "Field and Court Usage Report for Starlight Park : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ "Starlight Park Kayak/Canoe Launch Sites : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Making of America Project; Nature Publishing Group (1918). Scientific American. Library of American civilization. Munn & Company. pp. 524–525, 536–538. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 93.

- ^ a b c Gottlock & Gottlock 2013, p. 97.

- ^ "The Bronx International Exhibition". New-York Tribune. October 14, 1917. pp. 6–7. Retrieved October 2, 2019 – via The Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c d Twomey, Bill (2007). The Bronx – In Bits and Pieces. Bloomington, Indiana: Rooftop Publishing. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-1-600-08062-3. Retrieved December 30, 2012 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jaker, Bill (2008). The airwaves of New York : illustrated histories of 156 am stations in the metropolitan area, 1921- 1996. Jefferson, N.C: Mcfarland. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4766-0878-5. OCLC 908685721.

- ^ Ultan, Lloyd ; written in collaboration with the Bronx County Historical Society (1979). The Beautiful Bronx (1920-1950) (print). New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 0-87000-439-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MUSIC FESTIVAL IN BRONX.; Russian Symphony Orchestra Gives First Concert in Starlight Park". The New York Times. July 24, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "OPERA IN STARLIGHT PARK.; " Rigoletto" to Open the Summer Season on Saturday Night". The New York Times. May 25, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Dunford, Judith (August 13, 1995). "Remembrances of a War's End – The Real Starlight Park" (letter to editor). The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "20,000 Members of Kiddie Klub Merry at Outing". New York Evening World. July 13, 1921. pp. 1, 2 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Last Call for Starlight Park All Aboard for the Kiddie Klub". New York Evening World. July 25, 1922. p. 12. Retrieved October 16, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- Gottlock, Barbara; Gottlock, Wesley (2013). Lost Amusement Parks of New York City: Beyond Coney Island. Lost. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62584-556-6.

External links

- "Starlight Park Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 20, 1952. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Starlight Amusement Park at the Roller Coaster DataBase