Contents

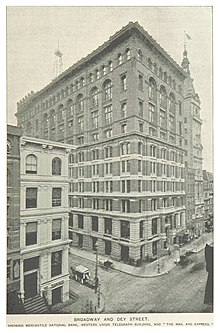

The Western Union Telegraph Building was a building at Dey Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The Western Union Building was built with ten above-ground stories rising 230 feet (70 m). The structure was originally designed by George B. Post, with alterations by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh. It is considered one of the first skyscrapers in New York City.

Western Union decided to construct the building in 1872 after outgrowing a previous space at 145 Broadway. Post was selected as the winner of an architectural design competition, and the building was completed in February 1875. At the time of its completion, it was one of the tallest structures in New York City, behind only Trinity Church, the New York Tribune Building, and the Brooklyn Bridge towers. The original design contained eleven stories, including the ground story. It had a three-story mansard roof and a clock tower whose pinnacle gave the building its 230-foot height. The interior included executive offices, a large telegraph operating room, and office space that could be rented to other tenants.

The top five stories were destroyed by fire in 1890, although the superstructure of the ground story and the lowest five floors remained intact. Hardenbergh designed a four-story flat-roofed expansion to the structure, completed in 1891. AT&T, which acquired the Western Union Telegraph Building, decided to redevelop the site with a 29-story building at 195 Broadway, which was completed in 1916. The old Western Union Building was demolished between 1912 and 1914, although Western Union continued to occupy the replacement structure until 1930.

Site

The Western Union Building was at the northwestern corner of Broadway and Dey Street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. The building originally occupied 75 feet (23 m) along Broadway to the east and 150 feet (46 m) along Dey Street to the south.[1][2][3] The rear boundary of the site, on the west, was slightly wider at about 78 feet (24 m).[4] The site initially took up five land lots in total: three on Broadway, each measuring 25 by 100 feet (7.6 by 30.5 m), and two on Dey Street, each measuring 25 by 78 feet (7.6 by 23.8 m).[5] Dey Street sloped downward away from Broadway, so that while the basement was half a level below Broadway, it was at the same level as Dey Street at the western end of the site.[6] When the Western Union Building was renovated in 1890, an additional lot on Dey Street was acquired for the expansion, measuring 25 by 100 feet (7.6 by 30.5 m).[7]

Architecture

The Western Union Building was originally designed by architect George B. Post and opened as the headquarters of Western Union in 1875.[8][9] The Western Union Building was designed in the Neo-Grec style with Beaux-Arts influences,[10][11] although at the time of its construction, the style was characterized as French Renaissance.[11] Numerous contractors provided material for the original building.[2][a] After the structure was severely damaged in an 1890 fire, it was rebuilt in 1892 to designs by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh.[12]

The building was ten stories tall (including a half-story attic), rising to a height of 230 feet (70 m) at the tip of its clock tower.[13][14][b] The height of the outer walls, below the mansard roof, was 140 feet (43 m).[16][17] The ground story was considered a fully raised basement, and the floor numbering started above the ground story.[18][c] The clock tower made the Western Union Building one of the tallest structures in New York City, after Trinity Church, the New York Tribune Building, and the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge.[20] At the time of the Western Union Building's completion, the city's tallest buildings were typically not taller than six stories, and church spires only rose to nine stories.[10] This was attributed to the fact that the elevator was still a relatively new technology.[10][21]

Facade

The articulation originally consisted of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column (namely a base, shaft, and capital).[10][22] The granite blocks used in the structure came from Quincy, Massachusetts, and Richmond, Virginia, while the brick came from Baltimore.[16] Above the base, the spandrels between the windows on each floor were recessed between the vertical piers, which separated the facades into bays.[11] On the Broadway facade, the second and fifth piers from south were designed to be wider, thereby supporting the clock tower and mansard roof above. The ornamentation of the Western Union Building was generally not as prominent as its main structural features.[23][24]

The base of the Western Union Building, comprising the lowest three stories, was clad with rusticated blocks of granite.[22] The main entrance was through a flight of stairs at the center of the Broadway facade, although there was also a direct entrance to the basement at the western end of the Dey Street facade.[25] Two pairs of Quincy granite columns flanked the main entrance. A stone balcony above the main entrance carried bronze sculptures of Samuel Morse and Benjamin Franklin.[26] The bronze sculptures may have been created by Launt Thompson, whom Post had recommended to Western Union.[2] Quincy granite was also used for the pilasters that ran around the base.[27]

The walls on the third through sixth floors consisted of alternating horizontal strips of Baltimore brick and Richmond granite.[28][22] The facade of the shaft was visually distinct from that of the base, with materials that were less heavy, less expensive, and more uniform in pattern.[10] The sixth story had low windows and a balcony with iron railings ran above it.[29] The exterior walls of the seventh floor, at the level of the balcony, were designed to let light into that floor and reduce the load on the walls in the floors below.[30]

The original roof was a three-story mansard roof, which contained the eighth through tenth stories.[31] The mansard roof was constructed by J. B. and J. M. Cornell.[32] The building was topped by a clock tower, which was one of the tallest structures in the city at its completion.[33] The centers of the clock faces were 184 feet (56 m) above street level.[17][28] Beginning in 1877, a time ball was dropped from the top of the building at exactly noon, triggered by a telegraph from the National Observatory in Washington, D.C.[34][35] According to a Western Union publicity director, the clock and time ball were used by "people on ships, in New Jersey, on Long Island and far north on Manhattan Island".[36] The time-ball system, invented by George May Phelps, was used as the initial reference for standard railway time starting in 1883;[37][38] it also directly inspired One Times Square's New Year's Eve "ball drop", an annual event since 1907.[39]

The sixth and seventh stories and the mansard roof burned in 1890. They were replaced with a four-story, flat-roofed expansion.[23] The reconstructed upper floors were designed in a distinct style compared to the lowest five floors and the ground story.[40][41] Unlike at the base and the shaft, the upper floors lacked any granite bands. There were semicircular arched windows above the sixth through eighth floors and smaller semicircular arched windows at the ninth floor.[41] The time ball was placed in a cage atop the expansion, about 300 feet (91 m) above street level.[42]

Features

The superstructure was mainly made of metal.[10] The cylindrical columns, made of cast iron, supported floor beams that were 10 inches (250 mm) deep.[36] The building was advertised as fireproof, using only a minimal amount of wood.[36][43] However, similar structures with iron columns had collapsed during the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, either because of extreme heat or when they were suddenly chilled by water from fire hoses. Nonetheless, the steel superstructure was left exposed in the Western Union Building and largely survived the 1890 fire.[36] The mansard roof was constructed of iron beams, supported only along the outer walls, thereby reducing the number of columns needed for the seventh floor.[31] The iron-truss beams that supported the top of the mansard roof were 65 feet (20 m) long.[9][36]

The floors consisted of brick arches between 10-inch (250 mm) iron beams.[44] The brick-arched floors were covered with Beton Coignet artificial stone tile, surrounded by a border of encaustic tile. The hallways were covered entirely in encaustic tiles.[16] The Western Union Building also contained plaster-block wall partitions and plastered ceilings.[36]

Interior

The Western Union Building served as a corporate headquarters, with clerical and operational departments.[6] There were two basement levels. The first basement level contained the packing room of the supply department, where goods were assorted and items were packed, while the second basement contained the engine room.[45] The ground story contained numerous departments. The treasurer's office had a separate entrance from Broadway and had a vault beneath the main entrance steps. Just inside the main door was a public passageway 80 feet (24 m) long and 19 feet (5.8 m) wide, which ran west-east parallel to Dey Street. On one side of the hall was a continuous mahogany counter for Western Union's cable, general message, city, and delivery departments. The hall connected to the elevator lobby and a ladies' waiting room. At the rear, or western, end of the ground story was the supply department and the office of the keeper of stores. The floor surface of the ground story was laid with encaustic tile in mosaic.[46] The first and second floors were originally used as rental floors, while the third through fifth floors contained various offices.[47]

On the original sixth floor was the battery room, which contained the inbound and outbound telegraph wires and thousands of cells that generated power for the telegraphs.[29][d] This story had a ceiling of 9 feet (2.7 m) and was lit by low windows.[3] Wires ran into the battery room from the balcony surrounding the seventh floor.[3][48] There were wardrobe rooms for operators on the sixth floor as well.[49] The battery room had been moved to the second basement prior to the 1890 fire.[7]

The original seventh floor, which contained the telegraph operating room, had dimensions of 145 by 70 feet (44 by 21 m) and a ceiling of 23 feet (7.0 m).[50] The seventh floor was largely free of obstructions, except for four iron columns on its eastern end, which supported the clock tower.[51] It was also illuminated well, with more than forty windows on all sides in addition to gas lamps.[52] There was a switchboard on the room's northern side, measuring 26 feet (7.9 m) long, 5.5 feet (1.7 m) wide,[53] which carried three hundred telegraph wires in total.[54] There were more than eighty mahogany operators' tables, each divided into four parts by glass partitions.[52] The different genders worked in a separate part of the room and were separated by a partition measuring 8 feet (2.4 m) tall.[55] The seventh-floor operating room had a ceiling fresco that depicted the sky.[56]

The original eighth through tenth stories were used as employee rooms and storerooms.[3][57] The eighth floor originally contained the bookkeeping department,[58] operators' lunchrooms,[59] the offices of the New York Associated Press,[60] and a water tank with a capacity of 5,000 U.S. gallons (19,000 L; 4,200 imp gal).[6] On the ninth floor were the kitchen, washing and drying rooms, refrigerators, and employee dining rooms. The tenth floor contained a message storeroom and another water tank.[61] A flight of stairs ran from the tenth floor to the clock tower.[62]

When the original sixth through tenth stories were destroyed in 1890, they were replaced with four flat-roofed stories. The new sixth floor was turned into offices, while the operating rooms were split between the new seventh and eighth stories.[7] The replacement operating rooms measured 75 by 200 feet (23 by 61 m) and were lit by thirty-six large windows. The seventh story had a commercial news department as well. There were ten switchboards across the operating rooms.[63] The new ninth story became a restaurant, kitchen, and servants' rooms.[7]

Utilities and elevators

In the cellar were six steam tubular boilers of 40 horsepower (30 kW) each; three were used to heat the building, while the other three were used to power the machinery, including the elevators, pneumatic tubes, and hoisters. On this floor were 18 wells, which were each sunk 50 feet (15 m) deep to a water stratum below the underlying layer of hardpan. The wells could extract a combined 300 U.S. gallons (1,100 L; 250 imp gal) of water per minute. Another pump could send up to 1,000 U.S. gallons (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) per minute to water tanks in the upper stories.[16] The wells were placed because Post or Western Union assumed the Croton Aqueduct would not provide enough water in case of a fire.[27]

The Western Union Building was built with three passenger elevators and one freight lift. The passenger elevators ran between the ground-level lobby and the fifth floor, while the smaller freight lift was powered by steam and extended between the cellar and the tenth floor. Two of the passenger elevators, for public use, were powered by steam and had a capacity of eighteen passengers each. The third passenger elevator, exclusively for Western Union employees, could fit fourteen passengers and was originally hydraulically powered.[64] The hydraulic employee elevator was hard for the elevator operator to control, so in 1891, it was replaced with a steam elevator.[27] A set of iron stairs also connected all floors.[65] The clock tower could be accessed by a flight of stairs.[62]

A pneumatic tube system delivered messages between the operating room and the ground-floor departments.[46] The pneumatic tubes from the operating room also connected to the Corn Exchange, the Produce Exchange, and an auxiliary Western Union office on Pearl Street.[66]

History

Western Union had been founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company.[12][67] It was renamed the Western Union Telegraph Company in 1856.[67][68] After it acquired several major competitors in the 1860s, Western Union became a major provider of transcontinental and transoceanic telegraph services in the late 19th century.[12][69][70] The company relocated to New York City from Rochester, New York, in 1866.[12][19] Its first New York City headquarters was at 145 Broadway, slightly south of the Western Union Building's site.[12]

Planning and construction

Western Union soon outgrew its headquarters at 145 Broadway,[71][72] and the company decided to search for a new headquarters under the leadership of president William Orton and main stockholder Cornelius Vanderbilt II.[73][70] At first, the company attempted to purchase the Astor House, across from the City Hall Post Office and Courthouse further north, although the acquisition was unsuccessful.[1][71][72] By March 1872, Western Union had purchased land at the northwest corner of Broadway and Dey Street, paying $840,000 to Thomas W. Evans, dentist for French emperor Napoleon III.[71][72][74] The company wanted to build a ten-story structure in which it would occupy three of the floors. According to architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern, the structure would also serve as "a visible representation of Western Union's virtual hegemony in its field and of the solidity of its leadership".[70] The company's directors voted in April 1872 to issue $1.5 million in bonds for the building's construction.[75]

Western Union held an architectural design competition for the building.[76] The competition, announced in March 1872, was only open to selected invited architects who submitted plans without their names attached. After the initial sketches were submitted, Western Union requested in-depth designs from three finalists.[77] Western Union did not commit to paying an appropriate architects' fee to the winning architect, so three of the invited architects declined to participate.[6][e] George Post had won the competition by July,[79][80] but not before a dispute arose with Western Union over compensation.[81] The compensation was a key concern for Post, who struggled to pay the high rent at his office in the Equitable Life Building.[8][6] By August 8, shortly after Post was selected as the architect, work had started on the foundations.[8][19]

Correspondence between Post and Orton indicated that plans for the substructure had been fully prepared by the end of August 1872.[8] Contractors began submitting bids for the basement work in September,[9][82] and the granite to be used in the basement had been prepared two months later. In March 1873, the main contractor was selected.[8] The original building plans indicated that the building would only be nine stories tall, but it was ultimately built with ten stories, excluding the ground story, which was considered a fully raised basement.[19] Initially, the building was slated to be completed in mid-1874, but work had only reached the seventh story by then. The deliveries of Richmond granite had been delayed because of a flood in the quarry where the granite was being procured.[83] The building was ready for occupancy by February 1, 1875.[17][84] It had cost $2.2 million in total to construct.[84]

Use

When the building opened, the first and second floors were leased to office tenants.[3][46] One room on the first floor was occupied by the editor of the Western Union Telegraph Company's paper, the Journal of The Telegraph.[85][40] The third through fifth floors were occupied by Western Union's executive officers; the electrician, auditor, tariff bureau, and general superintendents' offices; and the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company.[3][86] The northeast corner of the third floor contained the Western Union president's office.[87] Initially, the telegraph operating room was maintained by 290 operators, of which 215 were men and 75 were women.[55] The operating room was maintained 24 hours a day. According to an 1879 book, the room was staffed by over three hundred operators in the daytime and by one hundred operators at night.[88]

Electric lighting was installed in the building in 1883, supplanting the gas lighting system in use prior to then.[89] By 1886, Western Union took up the whole first floor and much of the third floor. The whole fifth floor and much of the fourth floor were rented to other companies.[40] The roof was slightly damaged in an 1889 fire, an incident that was described by the news media as demonstrating the fireproof quality of the building.[90] By 1890, the lowest five floors were occupied by the New York Associated Press and numerous railroad systems.[91]

On July 18, 1890, the roof and top floors were destroyed in a fire, surmised to have been caused by faulty electric wires.[40][91][92] The structure had been poorly equipped for fire protection, as it contained flammable objects in its storerooms, while having few egress routes.[40][93] The fifth floor, the highest floor that survived the fire, was cleared out to make way for a temporary operating room, but the remaining portion of the building was damaged by the water that had been used to extinguish the fire.[94] While the fire itself did not cause any deaths,[40] a workman removing debris died in the aftermath when a temporary debris-removal chute fell onto him.[95] Within four days of the fire, the operators had returned to work. Western Union officials had hired Post to survey the building to determine how the upper section of the building would be repaired.[96][97] Ultimately, Western Union decided to remove the top five stories and add a four-story flat-roof extension.[98] Hardenbergh was hired for the expansion, which was completed in 1891,[40][99] although the media were given a tour of the new operating room in 1892.[63] The expanded building occupied an additional lot at 14–18 Dey Street as well as the site of the older building.[7]

Demolition

In the first decade of the 20th century, Western Union began buying other lots on the same block.[100] Western Union was acquired by AT&T in 1909, and the following year, AT&T revealed plans to improve Western Union's offices "for the accommodation of the public and the welfare" of workers.[101] William W. Bosworth was offered the commission to design a headquarters building at 195 Broadway in November 1911.[42][102][103] He devised plans for a 29-story, white-faced building on Broadway from Dey Street to Fulton Street, on the site of the Western Union Building as well as the additional lots.[104] To minimize disruption to Western Union's operations, the new building was to be constructed in several portions, and the 195 Broadway Corporation was organized to take over operation of the existing structure.[105][106]

The Western Union Building annex at 14–18 Dey Street was demolished starting in 1912.[105] The New York Associated Press moved to 51 Chambers Street in April 1914,[107] and Western Union employees moved to a new structure at 32 Avenue of the Americas that June.[108] By that August, The Wall Street Journal reported that the old building was quickly demolished, stating, "The walls will soon be completely razed."[109] The new 195 Broadway building was declared to be completed in 1916.[104][105][110] Western Union continued to maintain their offices at 195 Broadway until 1930, when it moved to a new structure at 60 Hudson Street further north.[111]

Legacy

The Western Union Building's design received mixed criticism. The magazine The Aldine compared the Western Union Building to a cathedral, given that it was so prominent in the skyline of Lower Manhattan.[15] The New-York Tribune lamented that "for so marked a building a larger site [...] could not have been secured".[112] Alfred J. Bloor, addressing the American Institute of Architects shortly after the building's completion, felt that Post had made a mistake in using light-colored stone for the bands on the facade, as well as criticized the shaft and roof designs. Even so, he also stated his admiration for the design.[11][113][114] Post's involvement in the Western Union Building led Vanderbilt, then Western Union's main stockholder, to contract the design of his Fifth Avenue house to Post, despite the latter's relative inexperience in designing residences.[6] When the upper stories' reconstruction was completed, the Real Estate Record and Guide criticized the new design, saying, "The reconstructed building is now finished architecturally; we were about to say 'completed'; but that it can never be to the end of time. In mathematics, two halves may make a whole, but in architecture, they do not necessarily; and in the example in question most decidedly they do not."[99]

Later reviews also emphasized the building's importance. Architectural writer Winston Weisman stated in 1972 that the "basic principle" of architecture was "dictated by function", which Post "state[d] architecturally in refined form and in an exceptionally tall building where its message could not be missed".[23][115] Stern, writing in 1999, described the building as "a grand corporate monument, one of a handful of important buildings" that followed the completion of the Equitable Building.[1]

The initial structure has been described as one of three influential early skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, along with the Equitable Life Building and the New York Tribune Building.[116][117] The Tribune and Western Union Buildings are variously cited as being either the first-ever skyscrapers,[118] or the next major skyscrapers after the Equitable Life Building because of their substantial height increase.[119][120] Architectural historian Montgomery Schuyler wrote that the Tribune and Western Union Buildings were "much more visibly than the Equitable the products of the elevator", in reference to the Equitable Life Building's design, which gave it a diminished appearance.[121] The height difference from the Equitable was significant enough to attract attention from media reports such as the Graphic, which had written in 1873 that "the Western Union Building would be the loftiest business structure on Broadway twice the height of the five-story brownstone structure just north of it".[14]

References

Notes

- ^ These included:[2]

- James B. Smith & Prodgers Company, masonry and foundation

- J. B. & J. M. Cornell, iron

- J. G. Batterson and Andrews, Ordway & Green, granite

- N. Y. & L.I. Coignet & Co., concrete floors

- Anderson, Merchant & Co., encaustic tiling

- Joseph Cartessier, embossed glass

- Philip Herman, carpentry

- Locke & Monroe, plumbing and gas

- Otis Brothers, elevators

- ^ According to The Aldine magazine, the tip was 226 feet (69 m) above the street. By this calculation, the main roof would have been 174 feet (53 m) tall, and the flagpole atop the clock tower would have been 289 feet (88 m) tall.[15]

- ^ The Western Union Building was described using European floor numbering; i.e. the first story is directly above the ground floor. Architectural writers Sarah Landau and Carl Condit used U.S. floor numbering and counted the ground story as a first floor but excluding the attic.[19] Architectural writer Winston Weisman counted both the ground story and the attic, but treated the attic as half a floor.[14]

- ^ According to Reid 1879, p. 571, the batteries had an average of 15,000 cells. According to Western Union 1875, p. 50, there were 7,000 cells in use when the building opened, but there was capacity for up to 16,800 cells.

- ^ Griffith Thomas, Leopold Eidlitz, and Robert Griffith Hatfield refused to enter the competition as a result of the lack of commitment to compensation. The architects who participated but failed to receive the commission were Arthur Gilman, George Hathorne, Richard Morris Hunt, Napoleon LeBrun, and Russell Sturgis.[78]

Citations

- ^ a b c Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 396.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 408.

- ^ a b c d e f "The New Telegraph Building: How the Floors Are to Be Utilized". New-York Tribune. July 18, 1874. p. 2. ProQuest 572555261. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 408; Reid 1879, p. 568.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 568; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ a b c d e "The New Building Plans: What the New Western Union Will Be Like. The Appearance of the Reconstructed Edifice Will Be Wholly Different From That of the Old" (PDF). The New York Times. July 23, 1890. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Balmori 1987, p. 348.

- ^ a b c Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Balmori 1987, p. 354.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e "Western Union Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 1, 1991. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 78–80; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, pp. 396, 398; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Weisman 1953, p. 18.

- ^ a b "Western Union Telegraph Building". The Aldine. Vol. 7, no. 13. January 1875. p. 258. JSTOR 20636937. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Reid 1879, p. 569; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b c "Local Miscellany: the New Telegraphic Heart of America". New-York Tribune. February 1, 1875. p. 12. ProQuest 572607815. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Reid 1879, pp. 570–573; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, pp. 49–51.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Weisman 1972, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 81; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 83.

- ^ Weisman 1972, p. 182.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 81; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 81.

- ^ a b Reid 1879, p. 569.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 80–81; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Reid 1879, p. 569; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 408; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 78; Weisman 1953, p. 13.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Reid 1879, p. 573.

- ^ "Telegraph Time Service: How City Clocks Are Regulated the Office on the Service in the Western Union Building—the Standard Clock—Question of International Time". New-York Tribune. February 13, 1882. p. 2. ProQuest 572953111. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80.

- ^ "George M. Phelps: Master Telegraph Instrument Maker and Inventor". www.telegraph-history.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "Turning Back the Hands; a Quiet Change to the Standard Time. Stopping the Pendulums in the City Clocks and in the Railroad Stations—the Movement Started" (PDF). The New York Times. November 19, 1883. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "What's Your Problem?". Newsday (Nassau Edition). December 30, 1965. p. 48. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landau & Condit 1996, p. 84.

- ^ a b "The Reconstructed Western Union Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 47, no. 1206. April 25, 1891. p. 647. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Old Western Union Building Soon To Go; Lower Broadway Landmark Will Be Replaced by a 26-Story Structure". The New York Times. November 19, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Sky Building in New York". The Building News. Vol. 45. September 7, 1883. pp. 363–364. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Reid 1879, p. 569; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ Reid 1879, pp. 569–570; Western Union 1875, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c Reid 1879, p. 570; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 83–84; Reid 1879, pp. 570–571.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 80–81; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 571; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 569; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Reid 1879, p. 569; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 49.

- ^ a b Reid 1879, p. 571; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 81; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Reid 1879, pp. 572–573; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 572; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 80; Reid 1879, p. 572; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Reid 1879, pp. 572–573; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 573; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ a b Reid 1879, p. 573.

- ^ a b "A Triumph in Mechanism: the Equipment of the Western Union's New Quarters". The New York Times. January 21, 1892. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 1016020692. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 81; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 573; Western Union 1875, p. 51.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 571.

- ^ a b Huurdeman, A.A. (2003). The Worldwide History of Telecommunications. Wiley - IEEE. Wiley. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-471-20505-0. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Brewer 1901, p. 22.

- ^ Brewer 1901, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Balmori 1987, p. 344.

- ^ a b c "The Real Estate Market". New York Daily Herald. March 8, 1872. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c "A New Business Centre" (PDF). The New York Times. March 8, 1872. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, pp. 396, 398.

- ^ "Napoleon's Finances". Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express. March 28, 1872. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "A New Building for the Telegraph Company". Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express. April 4, 1872. p. 4. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 78; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 396.

- ^ Balmori 1987, p. 347; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 408; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Balmori 1987, p. 347; Landau & Condit 1996, p. 78.

- ^ Balmori 1987, p. 353.

- ^ Balmori 1987, pp. 347–348; Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 398.

- ^ Balmori 1987, pp. 353–354.

- ^ "New Buildings in Progress: the Western Union Building—the Dry Dock Savings Bank—the New Fifth-Ave. Presbyterian Church". New-York Tribune. May 2, 1874. p. 3. ProQuest 572574181. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Reid 1879, pp. 568–569.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 570.

- ^ Reid 1879, pp. 570–571; Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Western Union 1875, p. 50.

- ^ Reid 1879, p. 572.

- ^ "New York Items: Edison's Lights to Be Introduced Into the Western Union Telegraph Building". Courier-Journal. March 7, 1883. p. 2. ProQuest 1082117055. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Western Union Building Damaged: the Loss Slight and No Interruption to the Company's Business Explosion and Flames in a Church". New-York Tribune. November 22, 1889. p. 3. ProQuest 573507190. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Flames at Work". Times Union. July 18, 1890. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Fire in the Air". The Evening World. July 18, 1890. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Reconstructed Western Union Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 46, no. 1167. July 26, 1890. p. 110. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "The Wires Are Working; Telegraph Service Being Put Into Shape. The Western Union Building in the Hands of Repairers – Business Transacted at Branch Offices" (PDF). The New York Times. July 20, 1890. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "Killed by a Falling Chute: Fatal Sequel of the Western Union Building Fire—another Man Hurt Seriously". New-York Tribune. July 31, 1890. p. 3. ProQuest 573609682. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Ready for Work Again: Three Hundred Telegraph Operators at Their Posts the Western Union Building a Busy Place—pushing the Repairs Rapidly". New-York Tribune. July 22, 1890. p. 1. ProQuest 573552112. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Repairs Go on Briskly: the Western Union Restoring Order Out of Confusion. Transmissions Still Subjected to Great Delay, but the System Almost in Working Order" (PDF). The New York Times. July 22, 1890. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Western Union Fire.: Plans for the Reconstructed Building -all Wires Working" (PDF). The New York Times. July 23, 1890. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "The Reconstructed Western Union Building". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 47, no. 1206. April 25, 1891. p. 647. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; Western Union Adds to Its Dey Street Holdings – Broadway Lots Sold on the Heights – Buyers for Houses in Fifth Avenue Section – Day's Dealings in Bronx Properties" (PDF). The New York Times. December 10, 1904. p. 14. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Western Union For More Improvements; Executive Board Pledges the Company Also to Increased Salaries Based on Merit". The New York Times. April 7, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Western Union to Build: Will Erect 26 Story Building at Broadway and Dey Street". New-York Tribune. November 19, 1911. p. 2. ProQuest 574839083. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Jacobs, Quentin Snowden (1988). William Welles Bosworth: Major Works (MS Thesis). Historic Preservation, Columbia University. p. 87.

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (April 23, 2000). "Streetscapes/AT&T Headquarters at 195 Broadway; A Bellwether Building Where History Was Made". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c "American Telephone and Telegraph Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; Private Dwellings the Feature of a Dull Market". The New York Times. December 11, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Associated Press to Move to-day; Will Take Larger Quarters in Emigrant Savings Bank Building" (PDF). The New York Times. April 6, 1914. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "State Fund Insurance; Big Employers Taking Out Policies – 4,000 Already Written". The New York Times. June 29, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Old Western Union Building Nearly Razed: New Structure to Rise on the Site to Cost About $4,000,000 and the Value of the Ground Is $2,575,000—power of Leases on Real Estate". Wall Street Journal. August 26, 1914. p. 6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 129443555. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Bosworth, William Welles (1917). "The Telephone and Telegraph Building, New York City". Architecture and Building. Vol. 49. W.T. Comstock Company. p. 4. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "Western Union Quits Its 55-year-old Home; Begins Moving Executive Offices From 195 Broadway to New West Broadway Building". The New York Times. August 12, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- ^ "New Building of the Western Union Telegraph Company—its Dimensions and Arrangements". New-York Tribune. April 25, 1873. p. 8. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Bloor, A. J. (October 12, 1876). "Annual Address". Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Institute of Architects. Vol. 10. pp. 29–30. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 399.

- ^ Weisman 1972, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (May 15, 1988). "In the New York Region; the Lost Skyscrapers of Bygone New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 62.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 62; Weisman 1953, p. 13.

- ^ Kaufmann, Edgar; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.); Fein, Albert; Hitchcock, Henry-Russell; Scully, Vincent Joseph; Weisman, Winston (1970). "A New View of Skyscraper History". The rise of an American architecture, etc. London: Pall Mall P. p. 125. OCLC 1121117656.

- ^ Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1992). Architecture: nineteenth and twentieth centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-300-05320-3. OCLC 702601662.

- ^ Schuyler, Montgomery (September 1909). "The Evolution of the Skyscraper". Scribner's Magazine. Vol. 46. p. 261. hdl:2027/umn.319510019200199. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

Sources

- Balmori, Diana (December 1987). "George B. Post: The Process of Design and the New American Architectural Office (1868–1913)". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 46 (4): 342–355. doi:10.2307/990273. JSTOR 990273.

- Brewer, A.R. (1901). Western Union Telegraph Company, 1851-1901. The Company.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- Reid, James D. (1879). The Telegraph in America: Its Founders, Promoters, and Noted Men. Telecommunications. Arno Press. ISBN 978-0-405-06056-4.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-027-7. OCLC 40698653.

- "The Western Union Telegraph Building". Journal of the Telegraph. Vol. 8, no. 4. Western Union Telegraph Company. 1875. pp. 49–51.

- Weisman, Winston (September 1, 1972). "The Commercial Architecture of George B. Post". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 31 (3). University of California Press: 176–203. doi:10.2307/988764. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 988764.

- Weisman, Winston (1953). "New York and the Problem of the First Skyscraper". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 12 (1): 13–21. doi:10.2307/987622. JSTOR 987622.

External links

Media related to Old Western Union Telegraph Building (Manhattan) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Old Western Union Telegraph Building (Manhattan) at Wikimedia Commons