Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Greenhouse gas sources

-

2Mitigation

-

2.1Policy

-

2.1.1Policy and Law

-

2.1.2Forest Law of the People's Republic of China (1998)

-

2.1.3Energy Conservation Law (2007)

-

2.1.4Renewable Energy Act (2009)

-

2.1.512th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015)

-

2.1.6The National Strategy for Climate Change Adaptation (2013)

-

2.1.7National Plan For Tackling Climate Change (2014-2020)

-

2.1.8Energy Development Strategy Action Plan (2014-2020)

-

2.1.9Law on the Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution (2016)

-

2.1.1013th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020)

-

-

2.2Emissions Trading

-

2.3Vehicles

-

2.4Eco-Cities

-

-

3Future Plans

-

4See also

-

5References

-

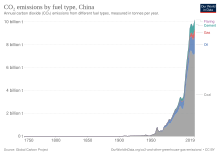

6External links

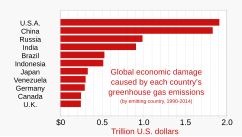

China's greenhouse gas emissions are the largest of any country in the world both in production and consumption terms, and stem mainly from coal burning, including coal power, coal mining,[3] and blast furnaces producing iron and steel.[4] When measuring production-based emissions, China emitted over 14 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2eq of greenhouse gases in 2019,[5] 27% of the world total.[6][7] When measuring in consumption-based terms, which adds emissions associated with imported goods and extracts those associated with exported goods, China accounts for 13 gigatonnes (Gt) or 25% of global emissions.[8]

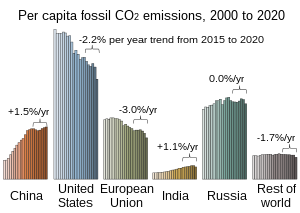

These high levels of emissions are due to China's large population; the country's per person emissions have remained considerably lower than those in the developed world.[8] This corresponds to over 10.1 tonnes CO2eq emitted per person each year, slightly over the world average and the EU average but significantly lower than the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the United States, with its 17.6 tonnes per person.[8] Accounting for historic emissions, OECD countries produced four times more CO2 in cumulative emissions than China, due to developed countries' early start in industrialization.[6][8] Overall, China is a net importer of greenhouse emissions.[9]

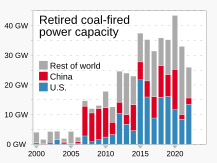

The targets laid out in China's nationally determined contribution in 2016 will likely be met, but are not enough to properly combat global warming.[10] China has committed to peak emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2060.[11] In order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C coal plants in China without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[12] China continues to build coal-fired power stations in 2020 and promised to "phase down" coal use from 2026.[13] According to various analysis, China is estimated to overachieve its renewable energy capacity and emission reduction goals early, but long-term plans are still required to combat the global climate change and meeting the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets.[14][15][16]

Greenhouse gas sources

Since 2006, China has been the world's largest emitter of CO2 annually. According to estimates provided by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, China's carbon dioxide emissions in 2006 amounted to 6.2 billion tons, and the United States' co-production in the same year was 5.8 billion tons. In 2006, China's carbon dioxide emissions were 8 percent higher than America's, the agency said. The U.S. emitted 2% more carbon dioxide in 2005 than China.[18] China ratified the Kyoto Protocol as a non-Annex B party without binding targets, and ratified the Paris Agreement to fight climate change.[19] As the world's largest coal producer and consumer country, China worked hard to change energy structure and experienced a decrease in coal consumption since 2013 to 2016.[20] However, China, the United States and India, the three biggest coal users, have increased coal mining in 2017.[21] The Chinese government has implemented several policies to control coal consumption, and boosted the usage of natural gas and electricity [citation needed]. Looking ahead, the construction and manufacturing industries of China will give way to the service industry, and the Chinese government will not set a higher goal for economic growth in 2018;[needs update] thus coal consumption may not experience continuous growth in the next few years.[20]

In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GhG, followed by the US with 11%, then India with 6.6%.[22]

China is implementing some policies to mitigate the bad effects of climate change, most of which aim to constrain coal consumption. The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) of China set goals and committed to peak CO2 emissions by 2030 in the latest, and increase the use of non-fossil fuel energy carriers, taking up 20% of the total primary energy supply.[23] If China successfully reached NDC's targets, the GHG emissions level would be 12.8–14.3 GtCO2e in 2030, reducing 64% to 70% of emission intensity below 2005 levels. China has surpassed solar deployment and wind energy deployment targets for 2020.[24][25]

Energy production

According to the Carbon Majors Database, Chinese state coal production accounts for 14% of historic global emissions, more than double the proportion of the former Soviet Union.[26]

Power is estimated as the largest emitter, with 27% of greenhouse gases produced in 2020 generated by the power sector.[7] Most electricity in China comes from coal, which accounted for 65% of the electricity generation mix in 2019. Electricity generation by renewables has been increasing, with the construction of wind and solar plants doubling from 2019 to 2020.[27]

According to a major 2020 study by Energy Foundation China, in order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C, coal plants without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[12]

Transport was estimated in 2021 to be less than 10% of the country's emissions but growing.[28]

According to Natural Resources Defense Council, the Chinese power sector is estimated to hit the carbon emission peak around 2029.[29]

Energy consumption

According to the 2016 Chinese Statistical Yearbook published by China's National Bureau of Statistics, China's energy consumption was 430,000 (10,000 tons of Standard Coal Equivalent), including 64% coal, 18.1% crude oil, 5.9% natural gas, 12.0% primary electricity, and other energy. Since 2011, the percentage of coal has decreased, and the percentage of crude oil, natural gas, primary electricity, and other energy have increased.[30]

China experienced an increase in electricity demand and usage in 2017 as the economy accelerated.[31] According to the Climate Data Explorer published by World Resources Institute, China, the European Union, and the U.S. contributed to more than 50% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[32] In 2016, China's greenhouse gas emissions accounted for 26% of total global emissions.[33] The energy industry has been the biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions since the last decade.[32]

Although China has large countrywide emissions, its per capita carbon dioxide emissions are still lower than those of some other developed and developing countries.

Industry

In terms of industrial production, China creates 1.26 Gt of greenhouse gases in 2020 and, judging by Climate Watch's chart, there is no downward trend at all. Industrial production accounts for 22.76% of all China's GHG emissions in the latest Climate Trace data for 2022.[7]

Cement

Cement is estimated to be 15% of emissions but only a tenth of companies are reporting data as of 2021.[34]

Iron and steel

Steel is estimated at 15% to 20% of emissions and consolidation of the industry may help.[35]

Transportation

A significant portion of greenhouse gas emissions also includes carbon dioxide exported by transportation. Although, China is now very successful in its transition to electric vehicles. According to ClimateWatch, China's transportation CO2 emissions account for 11% of global transportation GHG emissions, second only to the United States (21%). These figures are growing rapidly: between 2012 and 2019, China's CO2 emissions from transportation will grow at an average annual rate of 4%, placing it in second place among the top 10 countries with the highest transportation emissions in 2019, behind India at 5%.

Agriculture

Agriculture accounts for 7.65% of China's greenhouse gas emissions in 2022.[7] Methane emissions from food systems in China account for 34.1% of total emissions. Methane emissions mainly come from agricultural production and the exploration phase of mines. While methane accounted for only 13.2% of China's anthropogenic GHG emissions in 2018, the proportion of methane in GHG emissions from food systems is noteworthy. We find that N2O has the second highest share of GHG emissions at 14.1%, which is mainly attributed to agricultural production. Although fuel combustion contributes to N2O emissions, livestock manure management and fertilizer use in crop cultivation at the production stage are the main contributors.

Waste

China also produces large amounts of greenhouse gases such as methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the process of treating waste. In the 2022 Climate Trace statistics, waste treatment accounts for 7.06% of China's total greenhouse gas emissions. Waste disposal is the fourth largest source of GHG emissions in China, and landfills and incineration still dominate municipal waste disposal in China. As a result of the Chinese government's policy of mandatory waste separation in 11 prefectural-level cities, the GHG emissions from waste disposal are decreasing at an efficiency of 0.1% per year, which is effective, but the implementation of waste separation needs to be strengthened.[7] Most municipal solid waste is sent to landfill.[36]

Coal mine methane

China is by far the largest emitter of methane from coal mines.[3]

Mitigation

A 2011 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory report predicted that Chinese CO2 emissions will peak around 2030. This because in many areas such as infrastructure, housing, commercial building, appliances per household, fertilizers, and cement production a maximum intensity will be reached and replacement will take the place of new demand. The 2030 emissions peak also became China's pledge at the Paris COP21 summit. Carbon emission intensity may decrease as policies become strengthened and more effectively implemented, including by more effective financial incentives, and as less carbon intensive energy supplies are deployed. In a "baseline" computer model CO2 emissions were predicted to peak in 2033; in an "Accelerated Improvement Scenario" they were predicted to peak in 2027.[40] China also established 10 binding environmental targets in its Thirteenth Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). These include an aim to reduce carbon intensity by 18% by 2020, as well as a binding target for renewable energy at 15% of total energy, raised from under 12% in the Twelfth Five-Year Plan. According to BloombergNEF the levelized cost of electricity from new large-scale solar power has been below existing coal-fired power stations since 2021.[41]

Policy

The climate change mitigation policy in China is an important environmental protection strategy since the 2010s after rapid domestic developments. Having emitted the second-largest amount of greenhouse gas[42] and having the most people, China published a series of policies and laws to mitigate environmental impacts, such as reduce atmospheric pollution, transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, and achieve carbon neutrality.

In the past 20 years,[when?] China has published 4 legislative laws[43] and 5 executive plans[44] as outlines regarding the climate change issues. Government departments and local governments also developed their own special plans and implementation methods based on the national outline. In 2015 China joined the Paris Agreement to globally constrain the temperature rise and greenhouse gas emission.

In 2020 China created the 14th FYP(Five Year Plan) Archived 2020-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. The key climate- and energy-related ideas in the FYP will be critical to China's energy transition and global efforts to tackle climate change.[45]

In April, 2021, the United States and China decided to cooperate and reduce the global climate change. Series of international and domestic mitigation and adaption strategies was published based on the Paris Agreement.

Policy and Law

Forest Law of the People's Republic of China (1998)

The aim of this law was to conserve and rationally exploit forest resources. It accelerated territorial afforestation and cultivation while also ensuring forest product management, production, and supply in order to meet socialist construction requirements.[46]

Energy Conservation Law (2007)

The aim of this law was to strengthen energy conservation, especially for key energy-using institutions, as well as to encourage energy efficiency and energy-saving technology. The legislation allowed the government to promote and facilitate the use of renewable energy in a variety of applications.[47]

Renewable Energy Act (2009)

This Act outlines the responsibilities of the government, businesses, and other users in the production and use of renewable energy. It includes policies and targets relating to mandatory grid connectivity, market control legislation, differentiated pricing, special funds, and tax reliefs, as well as a target of 15 percent renewable energy by 2020.[48]

12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015)

The 12th Five-Year Plan sought to make domestic consumption and development more economically equitable and environmentally friendly. It also shifted the economy's focus away from heavy industry and resource-intensive manufacturing and into a more consumer-driven, resource-efficient economy.[49]

The National Strategy for Climate Change Adaptation (2013)

The strategy established clear guidelines and principles for adapting to and mitigating climate change. It includes interventions such as early-warning identification and information-sharing systems at the national and regional levels, an ocean disaster monitoring system, and coastal restoration to protect water supplies, reduce soil erosion, and improve disaster prevention.[50]

National Plan For Tackling Climate Change (2014-2020)

The National Plan For Tackling Climate Change is a national law that includes prevention, adaptation, scientific study, and public awareness. By 2020, China plans to reduce carbon emissions per unit of GDP by 40-45 percent compared to 2005 levels, raise the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to 15%, and increase forest area and stock volume by 40 million hectares and 1.3 million m3, respectively, compared to 2005 levels.[51]

Energy Development Strategy Action Plan (2014-2020)

This plan aimed to reduce China's high energy consumption per unit of GDP through a series of steps and mandatory goals, encouraging more productive, self-sufficient, renewable, and creative energy production and consumption.[52]

Law on the Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution (2016)

The aim of this law is to preserve and improve the environment, prevent and regulate air pollution, protect public health, advance ecological civilization, and promote economic and social growth that is sustainable. It demands that robust emission control initiatives be implemented against the pollution caused by the burning of coal, industrial production, motor vehicles and vessels, dust as well as agricultural activities.[53]

13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020)

The 13th Five Year Plan published the strategy and pathway for China's development during 2016-2020 and set specific environmental and productivity goals. Peak goals for carbon emissions, energy use, and water use were established in the 13th Five Year Plan. It also stated objectives for increasing industry productivity, removing obsolete or overcapacity production facilities, increasing renewable energy production, and improving green infrastructure.[54]

Emissions Trading

The Chinese Ministry of Finance originally proposed a carbon tax in 2010, to come into effect in 2012 or 2013.[55][56] The tax was never passed; in February 2021 the government instead set up a carbon trading scheme.[57][58][59]

The Chinese national carbon trading scheme is an intensity-based trading system for carbon dioxide emissions by China, which started operating in 2021.[60] This emission trading scheme (ETS) creates a carbon market where emitters can buy and sell emission credits. The scheme will allow carbon emitters to reduce emissions or purchase emission allowances from other emitters. Through this scheme, China will limit emissions while allowing economic freedom for emitters.

China is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG) and many major Chinese cities have severe air pollution.[61] The scheme is run by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment,[60] which eventually plans to limit emissions from six of China's top carbon dioxide emitting industries.[62] In 2021 it started with its power plants, and covers 40% of China's emissions, which is 15% of world emissions.[63] China was able to gain experience in drafting and implementation of an ETS plan from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), where China was part of the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).[61] China's national ETS is the largest of its kind,[63] and will help China achieve its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.[61] In July 2021, permits were being handed out for free rather than auctioned, and the market price per tonne of CO2e was around RMB 50, far less than the EU ETS and the UK ETS.[63]Vehicles

Vehicles account for around 8% of the heat-trapping gases released annually in China.[64] As the Chinese vehicle stock rises and heavy manufacturing as a percentage of the overall economy declines, this percentage will rise in the coming years. Fuel performance regulations[citation needed] and funding for electric vehicles are two of the Chinese government's key policies on vehicle emissions. The government refers to vehicles fueled by non-petroleum fuels as "new energy vehicles," or "NEVs." Almost all NEVs in China today are battery-powered plug-in electric vehicles.

Eco-Cities

The Chinese government has strategically promoted Eco-Cities in China as a policy measure for addressing rising greenhouse gas emissions resulting from China's rapid urbanization and industrialization.[65] These projects seek to blend green technologies and sustainable infrastructure to build large, environmentally friendly cities nationwide.[66] The government has launched three programs to incentivize cities to undertake eco-city construction,[67] encouraging hundreds of cities to announce plans for eco-city developments.[68]

Future Plans

14th Five Year Plan (2021-2025)

The 14th FYP(Five Year Plan) was created in September, 2020 as the key climate- and energy-related plan that is critical to China's energy transition and global efforts to tackle climate change.

On September 22, 2020, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated: "China will increase its nationally determined contributions, adopt more powerful policies and measures, strive to reach the peak of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030, and strive to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060."

Of particular interest is how China will integrate into the FYP to achieve peak carbon before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. The plan will be seen by many as a test of how seriously the pledge is being taken at the policy level.[69]

Unlike most nations that have committed to carbon neutrality, China's economy grows rapidly. China is still a developing country and, as of 2020, growth was still linked to carbon emissions. In the 14th Five Year Plan, the Chinese government revealed climate mitigation goals including higher share of non-fossil fuels in the energy mix, reduction of CO2 emissions per unit of GDP, carbon cap for the power sector, reduction of fine particle pollution in key cities, and greater forest coverage. These goals cover industrial production, transportation, forestry, and citizens’ daily life aspects.[69]

U.S.-China Cooperation

On April 15 and 16, 2021, U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and China Special Envoy for Climate Change Xie Zhenhua met in Shanghai to discuss aspects of the climate crisis. U.S. and China Finally released joint statement and decided to cooperating with each other and with other countries to tackle the climate crisis. According to the joint statement on U.S. Department of State, "This includes both enhancing their respective actions and cooperating in multilateral processes, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement."

In short term, The United States and China take following actions to further address the climate crisis:

- Both countries intend to develop by COP 26 in Glasgow their respective long-term strategies aimed at net zero GHG emissions/carbon neutrality.

- Both countries intend to take appropriate actions to maximize international investment and finance in support of the transition from carbon-intensive fossil fuel based energy to green, low-carbon and renewable energy in developing countries.

- They will each implement the phasedown of hydrofluorocarbon production and consumption reflected in the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

In addition, both countries will continue to discuss concrete actions in the 2020s to reduce emissions aimed at keeping the Paris Agreement-aligned temperature limit within reach. Potential areas include policies, measures, and technologies to decarbonize industry and power; Increased deployment of renewable energy; Green and climate resilient agriculture; Energy efficient buildings; Green, low-carbon transportation; Cooperation on addressing emissions of methane and other non-CO2 greenhouse gases; Cooperation on addressing emissions from international civil aviation and maritime activities; and other near-term policies and measures, including with respect to reducing emissions from coal, oil, and gas.[70]

Energy efficiency

In 2004, Premier Wen Jiabao promised to use an "iron hand" to make China more energy efficient.

Energy efficiency improvements have somewhat offset increases in energy output as China continues to develop. Since 2006, the Chinese government has increased export taxes on energy-inefficient industries, reduced import tariffs on certain non-renewable energy resources, and closed down a number of inefficient power and industrial plants. In 2009, for example, for every two new plants (in terms of energy generation capacity) built, one inefficient plant was closed. China is unique in its closing of so many inefficient plants.[71]

Renewable energy

China is the world's leading investor in wind turbines and other renewable energy technologies[72][73] and produces more wind turbines and solar panels each year than any other country.[74]

As the current largest greenhouse gas contributor in the world, coal burning is the major cause of global warming in China. Therefore, China has tried to transit from fossil fuels toward renewable energy since 2010.

China is the world leader in renewable energy deployment, with more than twice the ability of any other nation. China accounted for 43% of global renewable energy capacity additions in 2018.[75] For decades, hydropower has been a major source of energy in China. In the last ten years, wind and solar power have risen significantly. Renewables accounted for approximately a quarter of China's electricity generation in 2018, with 18% coming from hydropower, 5% from wind, and 3% from solar.[75]

Nuclear power is planned to be rapidly expanded. By mid-century fast neutron reactors are seen as the main nuclear power technology which allows much more efficient use of fuel resources.[76]

China has also dictated tough new energy standards for lighting and gas kilometrage for cars.[77] China could push electric cars to curb its dependence on imported petroleum (oil) and foreign automobile technology.

Co-benefits

Like India, cutting greenhouse gas emissions together with air pollution in China, saves enough lives to easily cover the cost.[78]

A temporary slowdown in manufacturing, construction, transportation, and overall economic activity during the beginning of the 2019–20 coronavirus outbreak reduced China's greenhouse gas emissions by "about a quarter," as reported in February 2020.[79][80] Nonetheless, for the year April 1, 2020 – March 31, 2021, China's CO2 emissions reached a record high: nearly 12 billion metric tons. Additionally, China's carbon emissions during the first quarter of 2021 were higher than in the first quarters of both 2019 and 2020.[81] Temporary reductions in carbon emissions due to lockdowns and initial economic relief efforts have limited long-term consequences, while the future direction of fiscal stimulus plays a more significant role in influencing long-term carbon emissions.[82]

Targets

The targets laid out in China's Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) in 2016 will likely be met, but are not enough to properly combat global warming.[10] China also established 10 binding environmental targets in its Thirteenth Five-Year Plan (2016-2020). These include an aim to reduce carbon intensity by 18% by 2020, as well as a binding target for renewable energy at 15% of total energy, raised from under 12% in the Twelfth Five-Year Plan. The Thirteenth Five-Year Plan also set, for the first time, a cap on total energy use from all sources: no more than 5 billion tons of coal through 2020.[83]

See also

- Debate over China's economic responsibilities for climate change mitigation

- List of countries by greenhouse gas emissions

References

- ^ "Historical GHG Emissions / Global Historical Emissions". ClimateWatchData.org. Climate Watch. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. ● Population data from "List of the populations of the world's countries, dependencies, and territories". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 June 2021.

- ^ Chart based on: Milman, Oliver (12 July 2022). "Nearly $2tn of damage inflicted on other countries by US emissions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Guardian cites Callahan, Christopher W.; Mankin, Justin S. (12 July 2022). "National attribution of historical climate damages". Climatic Change. 172 (40): 40. Bibcode:2022ClCh..172...40C. doi:10.1007/s10584-022-03387-y. S2CID 250430339.

- ^ a b Ambrose, Jillian (2019-11-15). "Methane emissions from coalmines could stoke climate crisis – study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-11-15. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ "Analysis: China's carbon emissions grow at fastest rate for more than a decade". Carbon Brief. 2021-05-20. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ^ "Preliminary 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimates for China". Rhodium Group. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ a b Bloomberg News (6 May 2021). "China's Emissions Now Exceed All the Developed World's Combined". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b c d e "CO2 Emissions: China - 2020 - Climate TRACE". climatetrace.org. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ a b c d Larsen, Kate; Pitt, Hannah (6 May 2021). "China's Greenhouse Gas Emissions Exceeded the Developed World for the First Time in 2019". Rhodium Group.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (7 October 2019). "How do CO2 emissions compare when we adjust for trade?". Our World in Data.

- ^ a b "To prevent catastrophic global warming, China must hang tough". The Economist. 2019-09-19. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2019-10-04. Retrieved 2019-10-04.

- ^ "China aims to cut its net carbon-dioxide emissions to zero by 2060". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- ^ a b China's New Growth Pathway: From the 14th Five-Year Plan to Carbon Neutrality (PDF) (Report). Energy Foundation China. December 2020. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

- ^ "Why China's climate policy matters to us all". BBC News. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ "China on Track to Blow Past Xi's Clean Power Goal Five Years Early". Bloomberg News. 28 June 2023.

- ^ "China's CO2 emissions fall but policies still not aligned with long-term goals". Reuters. 21 November 2022.

- ^ "China Climate Action". Climate Action Tracker.

- ^ a b Friedlingstein et al. 2019, Table 7.

- ^ "China now no. 1 in CO2 emissions; USA in second position". PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Archived from the original on 2019-07-09. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "It Didn't Take Long for China to Fill America's Shoes on Climate Change". Time. Archived from the original on 2018-03-29. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

- ^ a b Lu, Qi Ye and Jiaqi (2018-01-22). "China's coal consumption has peaked". Brookings. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ^ Daigle, Matthew Brown and Katy. "Coal on the rise in China, U.S., India after major 2016 drop". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ^ "Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined". BBC News. 2021-05-07.

- ^ "What is an INDC? | World Resources Institute". www.wri.org. 2014-10-17. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ^ "China - Climate Action Tracker". ClimateActionTracker.org. Archived from the original on 2018-04-04. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ^ "China greenhouse gas emissions soar 50% during 2005-2014 - government data". Reuters. 2019-07-15. Archived from the original on 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2024-04-03). "Just 57 companies linked to 80% of greenhouse gas emissions since 2016". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ "China doubles new renewable capacity in 2020; still builds thermal plants". Reuters. 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Xu, Xingbo; Xu, Haicheng (2021). "The Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions in China's Transportation Sector: A Spatial Analysis". Frontiers in Energy Research. 9: 225. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.664046. ISSN 2296-598X.

- ^ Schmidt, Jake (18 January 2022). "China's Top Industries Can Peak Collective Emissions in 2025". Natural Resources Defense Council.

- ^ "China Statistical Yearbook-2016". www.stats.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ "2017 electricity & other energy statistics | China Energy Portal | 中国能源门户". China Energy Portal | 中国能源门户. 2018-02-06. Archived from the original on 2018-04-15. Retrieved 2018-04-15.

- ^ a b "全球温室气体排放数据(最新版)_中国碳排放交易网". www.tanpaifang.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

- ^ Olivier, J.G.J.; Schure, K.M.; Peters, J.A.H.W. (2017). "Trends in global CO2 and total greenhouse gas emissions: 2017 Report" (PDF). PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-19. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "Concrete needs to lose its colossal carbon footprint". Nature. 597 (7878): 593–594. 2021-09-28. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..593.. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02612-5. PMID 34584258. S2CID 238218462.

- ^ Staff (2021-09-07). "Analysis: China's steel industry consolidation gathers pace, to aid output and emission cuts". www.spglobal.com. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- ^ "Sustainable waste management for zero waste cities in China: potential, challenges and opportunities".

- ^ a b "Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Shared attribution: Global Energy Monitor, CREA, E3G, Reclaim Finance, Sierra Club, SFOC, Kiko Network, CAN Europe, Bangladesh Groups, ACJCE, Chile Sustentable (5 April 2023). "Boom and Bust Coal / Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline" (PDF). Global Energy Monitor. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ ChinaFAQs: China's Energy and Carbon Emissions Outlook to 2050, ChinaFAQs on 12 May 2011, "ChinaFAQs: China's Energy and Carbon Emissions Outlook to 2050 | ChinaFAQs". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ^ Runyon, Jennifer (2021-06-23). "Report: New solar is cheaper to build than to run existing coal plants in China, India and most of Europe". Renewable Energy World.

- ^ "Cumulative CO2 emissions globally by country 2019". Statista.

- ^ "Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "The 14th Five Year Plan: what ideas are on the table?".

- ^ "Forest Law of the People's ... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "Energy Conservation Law - China - Climate Change Laws of the World".

- ^ "Renewable Energy Act (Legis... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World)". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "12th Five-Year Plan for the... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "The National Strategy for C... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "National Plan For Tackling ... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "Energy Development Strategy... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "Law on the Prevention and C... - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ "13th Five-Year Plan - China - Climate Change Laws of the World". climate-laws.org.

- ^ Jiawei, Zhang (11 May 2010). "China ministries propose carbon tax from 2012 -report". China Daily. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "China ministries propose carbon tax from 2012 -report". Alibaba News. Reuters. 10 May 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Can China's new carbon market take off?". The Economist. 2021-02-27. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ^ Xue, Yujie (16 July 2022). "China's national carbon trading scheme marks one-year anniversary". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ Xue, Yujie (2 February 2022). "Turnover of China's carbon trading scheme to reach US$15 billion in 2030". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "China National ETS". Archived from the original on 2019-06-03.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Jeff (March 2016). "China's National Emissions Trading System" (PDF). Global Economic Policy and Institutions.

- ^ Fialka, ClimateWire, John. "China Will Start the World's Largest Carbon Trading Market". Scientific American. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ a b c "China's carbon market scheme too limited, say analysts". www.ft.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ "CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2018". IEA Webstore. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ Sandalow, David (July 2018). Guide to Chinese Climate Policy (PDF). New York: Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy. ISBN 978-1-7261-8430-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-02-27.

- ^ Hunter, Garfield Wayne; Sagoe, Gideon; Vettorato, Daniele; Jiayu, Ding (2019-08-11). "Sustainability of Low Carbon City Initiatives in China: A Comprehensive Literature Review". Sustainability. 11 (16): 4342. doi:10.3390/su11164342. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ de Jong, Martin; Yu, Chang; Joss, Simon; Wennersten, Ronald; Yu, Li; Zhang, Xiaoling; Ma, Xin (2016-10-15). "Eco city development in China: addressing the policy implementation challenge". Journal of Cleaner Production. Special Volume: Transitions to Sustainable Consumption and Production in Cities. 134: 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.083. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Xu, Miao (2023). "Developer-led new eco-cities in China - identification, assessment and solution of environmental issues in planning". Archived from the original on 2023-05-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Climate and energy in China's 14th Five Year Plan – the signals so far". China Dialogue. 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ "U.S.-China Joint Statement Addressing the Climate Crisis". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ Hager, Robert P. (5 October 2016). "Steven W. Hook and John Spanier". Democracy and Security. 12 (4): 333–337. doi:10.1080/17419166.2016.1236635. S2CID 151336730.

- ^ "China Leads Major Countries With $34.6 Billion Invested in Clean Technology - NYTimes.com". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- ^ "China steams ahead on clean energy". 26 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2019 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith, 30 January 2010, China leads global race to make clean energy Archived 2019-10-11 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ a b REN21. "Renewables 2019 Global Status Report". www.ren21.net. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Nuclear Power in China, Updated March 2012, World Nuclear Association, http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf63.html Archived 2013-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (4 July 2010). "China Fears Warming Effects of Consumer Wants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ^ Sampedro, Jon; Smith, Steven J.; Arto, Iñaki; González-Eguino, Mikel; Markandya, Anil; Mulvaney, Kathleen M.; Pizarro-Irizar, Cristina; Van Dingenen, Rita (2020-03-01). "Health co-benefits and mitigation costs as per the Paris Agreement under different technological pathways for energy supply". Environment International. 136: 105513. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2020.105513. hdl:10810/44202. ISSN 0160-4120. PMID 32006762.

- ^ Myllyvirta, Lauri (2020-02-19). "Analysis: Coronavirus has temporarily reduced China's CO2 emissions by a quarter". Carbon Brief. Archived from the original on 2020-03-04. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ Aronoff, Kate (2020-02-20). "The Coronavirus's Lesson for Climate Change". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Archived from the original on 2020-03-07. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

- ^ He, Laura (21 May 2021). "China's construction boom is sending CO2 emissions through the roof". CNN. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ Shao, Shuai; Wang, Chang; Feng, Kuo; Guo, Yue; Feng, Fan; Shan, Yuli; Meng, Jing; Chen, Shiyi (May 2022). "How do China's lockdown and post-COVID-19 stimuli impact carbon emissions and economic output? Retrospective estimates and prospective trajectories". iScience. 25 (5): 2. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j4328S. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104328. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 9118742. PMID 35602942.

- ^ "The 13th Five-Year Plan | U.S.-CHINA". www.uscc.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-11-14. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

Sources

- "Nationally Determined Contributions submitted to UN". www4.unfccc.int. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- China's New Growth Pathway: From the 14th Five-Year Plan to Carbon Neutrality (PDF) (Report). Energy Foundation China. December 2020. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-16. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

- Friedlingstein, Pierre; Jones, Matthew W.; O'Sullivan, Michael; Andrew, Robbie M.; et al. (2019). "Global Carbon Budget 2019". Earth System Science Data. 11 (4): 1783–1838. Bibcode:2019ESSD...11.1783F. doi:10.5194/essd-11-1783-2019. hdl:20.500.11850/385668. ISSN 1866-3508.