Contents

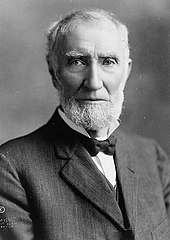

The 1908 U.S. Presidential election occurred in the backdrop of the Progressive achievements of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt's second term as well as against the U.S. recovery following the Panic of 1907.[1] In this election, Roosevelt's chosen successor, Republican William Howard Taft, ran in large part on Roosevelt's Progressive legacy and decisively defeated former Congressman and three-time Democratic U.S. Presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan (who also advocated progressive ideas in his campaign).[1][2] Overall, the 1908 presidential campaign and election were about labor issues, trusts, campaign finance reform, imperialism, and corruption.

Fight for the nomination

Democrat Alton Parker's defeat at the hands of President Theodore Roosevelt (who succeeded William McKinley after his assassination) in 1904 gave William Jennings Bryan, the 1896 and 1900 Democratic presidential nominee, an opening to reassert his leadership in the Democratic Party.[3] Bryan also was helped by newspaper tycoon and 1904 contender William Randolph Hearst's loss in the 1905 New York mayoral election, which hurt Hearst's chances to get the 1908 Democratic presidential nomination.[3] Bryan therefore was the front-runner.[3]

Bryan's most formidable challenger was Minnesota Governor John Albert Johnson.[3] Johnson's rags-to-riches story, honesty, reformist credentials, and ability to win in a heavily Republican U.S. state made him popular within the Democratic Party.[3] Johnson ultimately was unable to overcome Bryan,[3] and by the end of June 1908 Bryan had the two-thirds of the delegates needed to win the nomination.[3] At the 1908 Democratic National Convention, Johnson (who had no chance at the nomination by then) released his delegates to Bryan, helping Bryan to win the nomination on the first ballot with 892.5 votes to 105.5 votes for other (favorite son) candidates.[3] For Bryan's vice presidential running mate the convention delegates selected John W. Kern, a former state senator (1893–1897) and two-time gubernatorial candidate (and later U.S. Senator) from Indiana.[3] In response to Bryan's and Kern's nomination, The New York Times disparagingly pointed out that the Democratic national ticket was consistent because "a man twice defeated for the Presidency was at the head of it, and a man twice defeated for governor of his state [in 1900 and 1904] was at the tail of it."[3]

During the campaign, the fact that this was Bryan's third Democratic presidential nomination was mocked by Republicans.[4] Specifically, Republicans told voters to "[v]ote for Taft now[]" because they could "vote for Bryan anytime."[4]

Campaign

The 1908 Democratic platform criticized corporate power at the expense of the people as well as the increased number of federal officeholders and expenditures—"the heedless waste of the people's money"—and demanded "the strictest economy in every department compatible with frugal and efficient administration."[3] In addition, the Democrats condemned the "arbitrary power" of the Republican U.S. House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon (of Illinois) as well as the use of patronage by President Roosevelt to nominate "one of his Cabinet officers" (Taft) as his successor.[3]

Due to Bryan's efforts, a plank in the platform called for federal legislation requiring the publication of campaign contributions, limiting the amount that individuals could donate, and banning contributions from business corporations (via their officers), the last punishable by imprisonment.[3] The platform reiterated the party's longstanding support of tariff reform and welcomed Republicans' "tardy recognition of the righteousness of the Democratic position".[3] Labeling private monopoly "indefensible and intolerable," the trusts plank advocated three laws: banning directors from sitting on the board of more than one competing business, federal licensing of any corporation before it could control 25% of a market and prohibiting control of over 50% market-share of an American-consumed product, and requiring corporations to sell to all purchasers on the same terms (except for transportation costs).[3]

At Bryan's urging, his previous endorsement of government ownership of railroads was omitted from the platform.[3] The Democratic platform nevertheless advocated regulatory authority for the Interstate Commerce Commission, emergency currency "issued and controlled by the Federal Government," and an income tax on individuals and corporations.[3] Accepting most of the demands of Samuel Gompers, the President of the American Federation of Labor, the Democrats criticized the unfair use of injunctions against striking workers, affirmed the right of labor to organize and not be charged with restraining trade, and favored an eight-hour workday for federal employees, a general employers' liability law, and a separate Department of Labor.[3] Also, the Democrats advocated in support of a homestead law for Hawaii, territorial governments for Alaska and Puerto Rico, independence for the Philippines once a stable government was established, and a ban on Asian immigration to the United States.[3]

Unlike in 1896 and 1900, Bryan did not advocate in favor of free silver in 1908, believing this issue to be dead.[3][5][6] Rather, Bryan focused on labor issues, trusts, campaign finance reform, and imperialism during his campaign.[3][5][6] As in 1896 and 1900, Bryan ran an active and energetic campaign and delivered speeches throughout the North and West.[5][6] Of the 60 days that Bryan spent on the campaign trail, half were spent in the Midwest, 10 in New York, 6 in other Eastern states, and the remaining 14 days in the Plains States and Colorado.[5] Meanwhile, vice-presidential nominee Kern focused on campaigning in the South.[5] As in 1896 and 1900, Bryan attracted large crowds and gave numerous speeches each day (including a record-breaking 30).[5] Due to his older age, Bryan became more exhausted as a result of giving so many speeches than he was back in 1896 and 1900.[5] While he expected to lose New England and the West Coast, Bryan expected to hold the South and Rocky Mountain States (as he did in both 1896 and 1900).[5]

Late in the campaign, Bryan was hurt by his ties with Democratic National Committee treasurer and Oklahoma Governor Charles Haskell.[7] William Randolph Hearst revealed that both Haskell and Ohio Republican U.S. Senator Joseph Foraker accepting bribes in an attempt to stop the antitrust suit against the Standard Oil Company.[7] While Taft quickly cut off all of his ties with Senator Foraker, Bryan refused to do the same with Governor Haskell due to his refusal to believe the charges against Haskell.[7] In response, outgoing U.S. President Roosevelt called Bryan's association with and support of Haskell a "scandal and disgrace."[7]

Results

Taft defeated Bryan by a two-to-one (321 to 162) margin in the Electoral College and by a 52% to 43.5% margin in the popular vote.[7] Bryan did worse in 1908 than he did in both 1896 and 1900, carrying only the South, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Nevada (Bryan also won 6 of 8 electors in Maryland while losing the state to Taft by less than 0.30%).[7] Bryan won no crucial states and only won two large cities, Kansas City and New Orleans.[7] Taft did well in the more urban Northeast, the Midwest, and the Pacific Coast.[7]

While Bryan lost the election, Democrats picked up eight seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, gained strength in most state legislatures, and won governorships in five states that Taft carried that year.[7] In addition to this, and despite Bryan's loss, many of his proposed reforms from 1908 eventually became law, such as the direct election of senators (1913), a federal income tax (1913), and the government guarantee of bank deposits (1933).[7]

References

- ^ a b "HarpWeek | Elections | 1908 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ Milkis, Sidney M. (2013). "William Howard Taft and the Struggle for the Soul of the Constitution". In Postell, Joseph; O'Neill, Jonathan (eds.). Toward an American Conservatism. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 63–93. doi:10.1057/9781137300966_4. ISBN 978-1-137-30096-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "HarpWeek | Elections | 1908 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. 1906-08-30. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ a b Ostler, Rosemarie (2011-09-06). Slinging Mud: Rude Nicknames, Scurrilous Slogans, and Insulting Slang from ... - Rosemarie Ostler - Google Books. ISBN 9781101544136. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "HarpWeek | Elections | 1908 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ a b c "On This Day: July 18, 1908". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-09-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "HarpWeek | Elections | 1908 Overview". Elections.harpweek.com. Retrieved 2017-09-23.