Contents

The infantry in the American Civil War comprised foot-soldiers who fought primarily with small arms and carried the brunt of the fighting on battlefields across the United States. The vast majority of soldiers on both sides of the Civil War fought as infantry and were overwhelmingly volunteers who joined and fought for a variety of reasons. Early in the war, there was great variety in how infantry units were organized and equipped - many copied famous European formations such as the Zouaves - but as time progressed there was more uniformity in their arms and equipment.

Historians have debated whether the evolution of infantry tactics between 1861 and 1865 marked a seminal point in the evolution of warfare. The conventional narrative is that officers adhered stubbornly to the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars, in which armies employed linear formations and favored open fields over the usage of cover. However, the greater accuracy and range of the rifle musket rendered these tactics obsolete. The result was greater casualties and increasing usage of trench warfare, presaging the course of future conflicts. More recent scholarship has challenged this viewpoint and argued the impact of the rifled musket was minimal. In this interpretation, the tactics used remained practical and the decisiveness of battles was affected by other factors.

This debate has implications not only for the nature of the soldier's experience, but also for the broader question of the Civil War's relative modernity. Williamson Murray and Wayne Wei-Siang Hsieh argue that the conflict was resulted from "the combination...of the Industrial Revolution and French Revolution [which] allowed the opposing sides to mobilize immense numbers of soldiers while projecting military power over great distances."[1]

Outbreak of war

At the start of the war, the entire United States Army consisted of 16,367 men of all branches, with infantry representing the vast majority of this total.[2] Some of these infantrymen had seen considerable combat experience in the Mexican–American War, as well as in the West in various encounters, including the Utah War and several campaigns against Indians. However, the majority spent their time on garrison or fatigue duty. In general, the majority of the infantry officers were graduates of military schools such as the United States Military Academy.

In some cases, individual states, such as New York, had previously organized formal militia infantry regiments, originally to fight Indians in many cases, but by 1861, they existed mostly for social camaraderie and parades. These organizations were more prevalent in the South, where hundreds of small local militia companies existed to protect against slave insurrections.

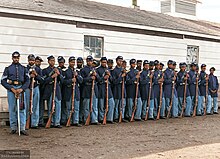

With the secession of eleven Southern states by early 1861 following the election of President Abraham Lincoln, tens of thousands of Southern men flocked to hastily organized companies, which were soon formed into regiments, brigades, and small armies, forming the genesis of the Confederate States Army (CSA). Lincoln responded by issuing a call for 75,000 volunteers, and later even more, to put down the rebellion, and the Northern states responded. The resulting forces came to be known as the Volunteer Army versus the professional Regular Army. More than seventeen hundred state volunteer regiments were raised for the Union Army throughout the war.[2] In all, approximately 80% of Union soldiers fought as infantry, while 75% of Confederate soldiers were infantry.[3]

Organization

The regiment was the foundational unit for mustering, training and maneuvering infantry during the Civil War.[4] The typical infantry regiment nominally consisted of about 1,000 soldiers organized into ten companies. It was commanded by a colonel (assisted by a lieutenant colonel and at least one major), with a dedicated headquarters and a band of musicians (the band later removed).[5][6] Regiments were designated by a number and the name of the state that raised them, such as the 10th New York or 48th Mississippi.[7] Each regiment also had their regimental colors, flags which not only served to denote position and alignment on the battlefield but which held special emotional significance. To be chosen as the color guard charged with protecting these flags was a special honor, and one of the most dangerous positions in the regiment.[8]

The actual authorized strength for a regiment could vary greatly. Within the Union Army there were three different regimental models: pre-war Regular Army regiments had an authorized strength of 878 soldiers; new Regular Army regiments created for the war were authorized up to 2,452 soldiers; and regiments raised by the states for the Volunteers Army ranged from 866 to 1,046. The Confederate States Army had their infantry regiments fixed to a maximum strength of 1,045, but they also experimented with forming legions, large regiments that combined infantry with cavalry and artillery. The concept was abandoned soon after the war began however for being too unwieldy.[7][9]

The official structure for regiments was not always followed: the 66th Georgia for example constituted 1,500 soldiers organized into thirteen companies at its formation, while the 14th Indiana was formed with 1,134 men. Nor did regiments stay at full strength. After just six months of duty, a regiment which started with 1,000 men often could muster only 600 or 700 on account of desertions, illness, detachment on special duty, and other factors. On average the fighting strength of a Civil War regiment was just 400 soldiers, with Union regiments having slightly more and Confederate regiments slightly less. Ironically, the smaller size of regiments had the unintended effect of making them more maneuverable and easier to command on the battlefield.[6]

The eventual fate of many regiments was to continue losing soldiers until they were deemed combat ineffective and either consolidated or disbanded.[6] Both armies made attempts to replenish regiments back to their full strength, but the process was haphazard and infrequent; nor was it helped by governors who preferred to meet their quotas by creating new regiments as a form of patronage. On the whole though, the Confederates put more effort into funneling replacements into existing regiments.[9][10]

Below the regiment was the battalion, although with few exceptions there was no formal structure, only that any two or more companies constituted a battalion.[4] If a regiment was formed with only eight or fewer companies, it was referred to as a battalion.[5] The company was traditionally seen as the smallest military unit and often recruited from a local community.[11] It's authorized strength was approximately 100 soldiers, led by a captain who was assisted by a couple of lieutenants and several non-commissioned officers (NCOs). However, as with regiments the actual strength of a company was often reduced to half or less.[7][12] A company could further split into two platoons, with each divided into two sections of two squads each. The smallest sub-unit were "comrades in battle" or the four men adjacent to each other in the line of battle. Such small units rarely featured in Civil War combat with some exceptions, such as during skirmishing.[13]

| unit | number |

|---|---|

| regiments | 642 |

| legions | 9 |

| battalions (separate) | 163 |

| companies (separate) | 62 |

| unit | number |

|---|---|

| regiments (Regular Army) | 19 |

| regiments (Volunteer Army) | 2,125 |

| battalions (separate) | 60 |

| companies (separate) | 351 |

Individual regiments (usually three to five, although the number varied) were organized and grouped into a larger body known as a brigade. A brigade was supposed to be commanded by a brigadier general, but it was often the case that the senior-most colonel would lead the unit. Confederate brigades usually combined regiments all from one state while Union brigades would mix regiments from different states.[9][12] Two or more brigades were combined into a division, usually commanded by a major general, with several divisions constituting a corps and multiple corps together making up an army.[12][15] In the beginning infantry divisions typically had cavalry and artillery units attached to them, although as the war progressed these were spun off into their own units under corps and army control. Union divisions were numbered based on their position within their corps, as were brigades within divisions. The same was true with Union corps at first, but they eventually came to be numbered irrespective of their army. For the Confederates corps were numbered within their respective armies, but divisions and brigades were identified by their commanding officer.[16] Confederate corps and armies were commanded by a lieutenant general and full general respectively, while major generals commanded both in Union forces.[12][15]

| unit type | low | high | average | most frequent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| corps per army | 1 | 4 | 2.74 | 2 |

| divisions per corps | 2 | 7 | 3.10 | 3 |

| brigades per division | 2 | 7 | 3.62 | 4 |

| regiments per brigade | 2 | 20 | 4.71 | 5 |

| unit type | low | high | average | most frequent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| corps per army | 1 | 8 | 3.71 | 3 |

| divisions per corps | 2 | 6 | 2.91 | 3 |

| brigades per division | 2 | 5 | 2.80 | 3 |

| regiments per brigade | 2 | 12 | 4.73 | 4 |

Starting at the regimental level, commanders had a staff of officers to help with the administration of their unit. Regimental staff officers were chosen from among the unit's lieutenants, while higher formations were to have a representative from the armies' respective War Departments. General officers were also allowed a personal staff of aides-de-camp and a chief of staff. Neither side had an effective way to train staff officers however, and so their competence tended to be based on how much experience they gained. Furthermore, with some exceptions there were no enlisted personnel authorized to assist in carrying out the logistical work necessary to keep these units supplied. Either civilian workers had to be hired or infantry soldiers detailed to handle these functions; the former tended to be unreliable while the latter lessened the combat effectiveness of their units.[18][19]

Infantry were accompanied by a train of wagons carrying the supplies they would need for a given campaign, although it was often necessary to supplement this by foraging or pillaging. The exact number of wagons needed depended on the number of soldiers and other factors, with commanders seeking to strike the right balance of sufficient supplies without slowing down the army with unnecessary wagons.[20] Once an ambulance corps was set up, infantry would also be accompanied by a number of ambulances to carry away the wounded (a task otherwise assigned to musicians).

Tactics

Both the Union and Confederate armies utilized a modified form of the linear tactics which defined the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.[21] These tactics were transmitted to American commanders in the form of manuals, the three principal ones being Winfield Scott's Infantry Tactics, or Rules for Manoeuvers of the United States Infantry (published in 1835), William J. Hardee's Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics: for the Instruction, Exercise and Maneuver of Riflemen and Light Infantry (1855), and Silas Casey's Infantry Tactics (1862).[22] Other popular instruction manuals included McClellan's Bayonet Drill (1862).

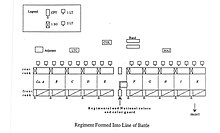

The core of these tactics was organizing soldiers into ranks and files in order to form a regiment into a line of battle or column.[21] The line was the primary formation of combat as it allowed the soldiers to fire a full volley at the enemy. Generally consisting of companies formed up into two ranks with files close enough to touch elbows, the line was held in alignment by placing the regimental colors in the center and a designated guide on either end of the line. File closers spread out just behind the line helped ensure order and prevented soldiers from deserting. Thus organized, a standard 475-man regiment occupied a front of 140 yards.[23] The column was primarily used for maneuvering, with a simple column consisting of companies stacked up behind one another at varying distances. More common was the double column consisting of two stacks of companies next to each other as doing so shortened the formation's length and widened its frontage. Infantry squares were rarely employed, both because they were the most difficult formation to carry out and because they were rarely necessary on Civil War battlefields.[24]

Of particular tactical importance was the usage of skirmishers, which historian Earl J. Hess argues reached its apogee during the Civil War. The textbook deployment of skirmishers was for a company to break into two platoons, one of which formed the skirmish line and the other a reserve 150 paces behind it. Soldiers deployed as skirmishers operated in groups of four known as "comrades in battle" spaced out at five-pace intervals, with spacing of twenty to forty paces between each group. Standard practice was for two companies to form a skirmish line for a regiment, while on a larger scale a regiment would form a skirmish line for a brigade. In essence a more advanced form of the line of battle, skirmish lines nevertheless required greater individual skill and determination of the soldiers forming it. They could act as a screen for a defensive line from oncoming enemy soldiers, harassing attackers as they approached, or probed an enemy's strength in preparation for an attack and screen the assaulting force. Some regiments were more adept at skirmishing than others, but most were adequate in the role.[25][26]

The most common means by which an infantry attack was carried out was with multiple or successive waves of battle lines approaching the enemy. Rather than having each line be formed of regiments under one commander, the proper way was to assign sectors of the battlefield to a commander so they could form successive lines with their own regiments, thereby allowing greater command and control. Successive lines were best spaced out a couple hundred yards from each other so that they were far enough away to avoid being hit by the same fire yet close enough to provide support.[27] The use of successive lines also necessitated an understanding how to pass one line through another, as doing so carelessly easily caused confusion. It was also common for successive lines to be organized into an echelon formation to protect an exposed flank or outflank an opposing line.[28] Obstacles such as buildings and ponds could be easily navigated by well-drilled units so as not to disrupt the battle lines, although linear impediments such as fences, waterways and road cuts could be fairly disruptive. However, the presence of thick woodlands (which might account for as much as half of the area of a given Civil War battlefield) could quickly render even veteran units confused and disorganized.[29]

Analysis

Infantry tactics in the Civil War had been developed around the use of the smoothbore musket, an inherently inaccurate weapon which (when combined with poor training and the general excitability of battle) was only effective at ranges of forty to sixty yards. For this reason emphasis was placed on volley fire to inflict damage on the enemy.[30][3] However the Civil War saw the widespread usage of rifled muskets which, utilizing the Minié ball, were capable of accurately hitting targets at ranges of up to 500 yards. This led contemporaries to predict the defender having a distinct advantage over the attacker and higher casualties in battle.[21] After the war, many veterans complained of an inappropriate devotion to Napoleonic tactics, conducting frontal assaults in tightly-packed formations and the casualties it would inevitably cause.[31] Such criticisms were picked up by later historians such as Edward Hagerman, writing that the rifled musket doomed the frontal assault and led to the introduction of trench warfare.[32]

More recently, historians have questioned this narrative and argued these tactics remained practical. Independent studies of Civil War battle records by Paddy Griffith, Mark Grimsley and Brent Nosworthy found that (despite the rifled musket's superiority) infantry combat most often took place at ranges similar to those of smoothbore muskets and the causality rates were little different than from earlier wars.[21] A number of factors are said to explain this seeming contradiction between technology and tactical reality. Allen Guelzo points out two technological limitations which reduced the rifled musket's effective range, the first being its continued use of black powder. The billowing clouds of smoke created from firing these weapons could become so thick as to reduce visibility to "less than fifty paces" and prevent accuracy at range. The second is that the unique ballistic properties of the Minié ball meant that it followed a curved trajectory which required a well-trained shooter to utilize it at range.[33]

These were compounded by the fact that target practice was for all intents and purposes nonexistent in both armies of the Civil War. While officers were encouraged to give their men this training, no funds were actually provided to carry them out.[34] The result of this deficiency was readily apparent. In one instance, forty men from the 5th Connecticut fired on a fifteen-foot high barn from a distance of one hundred yards: just four actually hit the barn, and only one at a height that would have hit a man. In another, a soldier of the 1st South Carolina remarked that the chief casualties from an intense firefight conducted at one hundred yards were the needles and pinecones from the trees above them. Highly-trained sharpshooters could utilize rifled muskets to their full potential but for most infantry a lack of training combined with the natural stresses of battle meant that the best one could do was "simply raise his rifle to the horizontal, and fire without aiming."[35] Likewise, Paddy Griffith also found no evidence that the elaborate earthworks of the Civil War were any more necessary to deal with modern rifle weaponry than they had been in previous wars. Instead he argues their increasing prevalence during the war was due to psychological reasons: a more risk-adverse populace combined with officers influenced by the defensive-oriented teachings of men like Dennis Hart Mahan.[36]

Hess argues that, given all these factors, the continued use of linear tactics by infantry in the Civil War were appropriate, and the most successful units were those most familiar with these tactics. An increase in volume of fire rather than range may have necessitate a change in tactics, but the breechloader and repeating firearms which promised to do so were simply not available in sufficient quantities until well after the war.[21]

Weapons and equipment

The standard weapon of infantry on both sides of the Civil War was the rifle musket, of which the Springfield Model 1861 and its derivatives was the most common. Rugged and simple to construct, "Springfields" as they were known had an effective range of 500 yards and were capable of firing three rounds a minute. Second-most common was the Pattern 1853 Enfield, purchased by both Union and Confederate governments during the war. It also came in several different models and was considered by some to be superior to the Springfield.[37][38] With the rifle the soldier was also given a bayonet with a scabbard to carry it, a cap box to carry percussion caps, and a cartridge box to store ammunition. The standard cartridge box could carry 40 rounds of ammunition, with additional bullets carried on the soldier's person.[38][39] Officers were typically armed with a revolver, the most popular being those produced by Colt, and both officers and sergeants traditionally carried a sword.[38][40]

However, soldiers in the Civil War could be armed with a variety of weapons, particularly in the early days when neither side was well equipped for the fight ahead. Many volunteers first showed up armed with hunting rifles, shotguns, or nothing at all. Even by 1863 when considerable effort had been made to arm soldiers with modern weapons, a significant number went into battle armed with second-rate rifles and smoothbore muskets; this was particularly true for Confederate armies or armies operating in the Western Theater. At the Battle of Gettysburg, even the well-equipped Army of the Potomac had only 70.8% of its regiments armed with either Springfields or Enfields, while 26.3% were armed wholly or in part with second-rate rifles or smoothbores (the rest were armed wholly or in part with breechloading rifles).[41] Given that most combat took place at ranges of 100 yards though, smoothbores remained a deadly option, especially as many soldiers loaded their muskets with buck and ball (a combination considered more lethal than Minié balls).[42]

In addition to his weapon and ammunition, the typical Union soldier usually had a knapsack and haversack to carry the rest of their gear. This included three to eight days' worth of marching or 'short' rations, a canteen, a blanket or overcoat, rubber ground cloth, a shelter-half, extra clothing, personal hygiene and other miscellaneous items (eating utensils, sewing kit, notebook, etc.). With arms and equipment, the total weight a soldier carried was approximately 45-50 pounds.[38][39] Confederate soldiers tended to be less well-equipped, and their material tended to be of lower quality than their Union counterparts. Both sides though were notorious for ditching anything they considered to be 'non-essential' during long hot marches or right before a battle; Union and Confederate soldiers for example often ditched their knapsack and would carry everything in a rolled-up blanket. Union General Irvin McDowell once observed that the amount of abandoned equipment he saw early in the war could've been used to equip a French army half their size.[38][39]

One primary account of the typical infantryman came from James Gall, a representative of the United States Sanitary Commission, who observed Confederate infantrymen of Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in camp in the occupied borough of York, Pennsylvania, in late June 1863, sometime after the Second Battle of Winchester.

Physically, the men looked about equal to the generality of our own troops, and there were fewer boys among them. Their dress was a wretched mixture of all cuts and colors. There was not the slightest attempt at uniformity in this respect. Every man seemed to have put on whatever he could get hold of, without regard to shape or color. I noticed a pretty large sprinkling of blue pants among them, some of those, doubtless, that were left by Milroy at Winchester. Their shoes, as a general thing, were poor; some of the men were entirely barefooted. Their equipments were light, as compared with those of our men. They consisted of a thin woolen blanket, coiled up and slung from the shoulder in the form of a sash, a haversack swung from the opposite shoulder, and a cartridge-box. The whole cannot weigh more than twelve or fourteen pounds. Is it strange, then, that with such light loads, they should be able to make longer and more rapid marches than our men? The marching of the men was irregular and careless, their arms were rusty and ill kept. Their whole appearance was greatly inferior to that of our soldiers... There were not tents for the men, and but few for the officers... Everything that will trammel or impede the movement of the army is discarded, no matter what the consequences may be to the men... In speaking of our soldiers, the same officer remarked: 'They are too well fed, too well clothed, and have far too much to carry.' That our men are too well fed, I do not believe, neither that they are too well clothed; that they have too much to carry, I can very well believe, after witnessing the march of the Army of the Potomac to Chancellorsville. Each man had eight days' rations to carry, besides sixty rounds of ammunition, musket, woollen blanket, rubber blanket, overcoat, extra shirt, drawers, socks, and shelter tent, amounting in all to about sixty pounds. Think of men, and boys too, staggering along under such a load, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day.[43]

Rapid-fire weapons

While thousands of repeating rifles and breechloaders, such as the 7-shot Spencer and 15-shot Henry models, were fielded to Union cavalry in the war, no significant funds were allocated to furnish Union infantry with the same equipment. With the exception of some volunteer regiments receiving extra funding from their state or wealthy commander, the small numbers of rapid-fire weapons in service with US infantrymen, often skirmishers, were mostly purchased privately by soldiers themselves.[44]

Despite President Lincoln's enthusiasm for these types of weapons, the mass adoption of repeating rifles for the infantry was resisted by some senior Union officers. The most common concerns cited about the weapons were their high-cost, massive use of ammunition and the considerable extra smoke produced on the battlefield. The most influential detractor of these new rifles was 67-year-old General James Ripley, the US Army's ordnance chief. He adamantly opposed the adoption of, what he called, "these newfangled gimcracks," believing they would encourage soldiers to "waste ammunition." He also argued that the quartermaster corps could not field enough ammunition to keep a repeater-armed army supplied for any extended campaign.[45]

One notable exception was Colonel John T. Wilder's mounted infantry "Lightning Brigade." Col. Wilder, a wealthy engineer and foundry owner, took out a bank loan to purchase 1,400 Spencer rifles for his infantrymen. The magazine-fed weapons were quite popular with his soldiers, with most agreeing to monthly pay deductions to help reimburse the costs. During the Battle of Hoover's Gap, Wilder's Spencer-armed and well-fortified brigade of 4,000 men held off 22,000 attacking Confederates, and inflicted 287 casualties for only 27 losses.[46] Even more striking, during the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, his Spencer-armed brigade launched a counterattack against a much larger Confederate division overrunning the Union's right flank. Thanks in large part to the Lightning Brigade's superior firepower, they repulsed the Confederates and inflicted over 500 casualties, while suffering only 53 losses.[47]

See also

- Cavalry in the American Civil War

- Field Artillery in the American Civil War

- List of American Civil War topics

References

- Boatner, Mark M. (1991). The Civil War Dictionary: Revised Edition. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73392-2.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Faust, Patricia L., ed. (1986). The Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-181261-7.

- Griffith, Paddy (1989). Battle Tactics of the Civil War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300042474.

- Hagerman, Edward (1992). The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253305466.

Primary sources

- Hardee, William J. Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics: For the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops when Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen (United States War Department, 1855), the main textbook in use. full text online

Notes

- ^ Murray, Williamson; Hsieh, Wayne Wei-lara (2016). A Savage War: A Military History of the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780691169408.

- ^ a b US Army, Center of Military History. "US Army Campaigns of the Civil War: The Regular Army before the Civil War, 1845-1860, p 50" (PDF). history.army.mil.

- ^ a b Guelzo, A. C. (2012). Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Italy. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 249-250

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 65

- ^ a b "Civil War Army Organization and Rank". North Carolina Museum of History. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Griffith, 91-93

- ^ a b c Coggins, J. (2012). Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. United States: Dover Publications. p. 21-22

- ^ Barney, W. L. (2011). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Spain: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 127

- ^ a b c Gudmens, J. J. (2005). Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6-7 April 1862. United States: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 4-6

- ^ Griffith, p. 94-96

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 66

- ^ a b c d Axelrod, A. (2017). Armies South, Armies North. United States: Lyons Press. p. 69-71

- ^ Hess, E. J. (2015). Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness. United States: LSU Press. p. 40

- ^ a b Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Perryville, 8 October 1862. (2005). Fort Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College. p. 5

- ^ a b Axelrod (2017), p. 63

- ^ Wilson, J. B. (1998). Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades. United States: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. p. 13-16

- ^ Eicher, p. 73.

- ^ Gudmens (2005), p. 7

- ^ United States Army Logistics, 1775-1992: An Anthology. (1997). United States: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. p. 198

- ^ United States Army Logistics, p. 206-208

- ^ a b c d e Hess, E. J. (2015). Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness. United States. LSU Press. Preface

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 29-36

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 37-42

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 49-53

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 53-55

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 95-102

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 106-113

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 114-118

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 87-88

- ^ Griffith, P. (2001). Battle Tactics of the Civil War. United Kingdom: Yale University Press. p. 73

- ^ Jamieson, P. D. (2004). Crossing the Deadly Ground: United States Army Tactics, 1865–1899. United Kingdom: University of Alabama Press. p. 1-4

- ^ Hagerman, E. (1992). The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. United States: Indiana University Press. Introduction.

- ^ Guelzo, A. C. (2012). Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Italy: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 253-254

- ^ Hess (2015), p. 32

- ^ Guelzo, A. (2014). Gettysburg: The Last Invasion. United States: Vintage Books. p. 37-41

- ^ Griffith (2001), p. 134-135

- ^ Coggins, J. (2004). Arms and Equipment of the Civil War. United Kingdom: Dover Publications. p. 32

- ^ a b c d e Axelrod (2017), p. 108-109

- ^ a b c United States Army Logistics, 1775-1992: An Anthology. (1997). United States: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. p. 199

- ^ Coggins (2004), p. 29

- ^ Griffith (2001), p. 76-77

- ^ Griffith (2001), p.74

- ^ Scott L. Mingus and Brent Nosworthy, The Louisiana Tigers in the Gettysburg campaign, June–July 1863 (2009) p 90 online

- ^ Redman, Bob. "The Spencer Repeating rifle". www.aotc.net. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- ^ Leigh, Phil (24 January 2012). "The Union's 'Newfangled Gimcracks'". Opinionator. Retrieved 2017-10-13.

- ^ Cozzens, Peter (1992). This terrible sound : the battle of Chickamauga. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 025201703X. OCLC 25165083.

- ^ "Battle of Chickamauga: Colonel John Wilder's Lightning Brigade Prevented Total Disaster | HistoryNet". www.historynet.com. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 2017-10-13.