Contents

The history of Saint John, New Brunswick is one that extends back thousands of years, with the area being inhabited by the Maliseet and Miꞌkmaq First Nations prior to the arrival of European colonists. During the 17th century, a French settlement was established in Saint John. During the Acadian Civil War, Saint John served as the seat for the administration under Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour. The French position in Saint John was abandoned in 1755, with British forces taking over the area shortly afterwards.

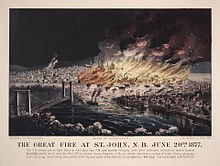

The area was incorporated into a city in 1785. During the 19th century Saint John saw an influx of Irish migrants, with the city becoming the third-largest city in British North America by 1851, after Montreal and Quebec. However, in 1877, the city was ravaged by a great fire. During the 1920s, the city saw itself at the centre of the Maritime Rights Movement. During the second half of the 20th century, the harbour and former railway lands of Saint John were redeveloped as a part of larger urban renewal projects.

Early history

Predated by the Maritime Archaic Indian civilization, the area of the northwestern coastal regions of the Bay of Fundy is believed to have been inhabited by the Passamaquoddy Nation several thousand years ago, while the Saint John River valley north of the bay became the domain of the Maliseet Nation. The Mi'kmaq also ventured into the territory and named the area ''Měnagwĕs'', which means "where they collect the dead seals."[1]

French colony (17th century–1758)

The mouth of the Saint John River was first discovered by Europeans in 1604 during a reconnaissance of the Bay of Fundy undertaken by French cartographer Samuel de Champlain. The day upon which Champlain sighted the mighty river was St. John The Baptist's Day, hence the name, which in French is Fleuve Saint-Jean. The city has the same name in both English and French.[2]

The strategic location at the mouth of the Saint John River was fortified by Charles de la Tour in 1631. The fort was named Fort Sainte Marie (AKA Fort La Tour) and was located on the east side of the river. To the west of the Saint John River, Fort Saint-Jean was later built.[3]: 14

Raid on St. John (1632)

Precipitated by the arrival of the new French governor of Acadia, Isaac de Razilly, on 18 September 1632, Captain Andrew Forrester, commander of the then Scottish community of Port Royal, Nova Scotia, crossed the Bay of Fundy with twenty-five armed men and raided Fort Sainte-Marie. Symbolically, Forrester's men knocked down the large wooden cross and arms of the king of France before plundering the fort. They seized the fort's personnel and their stock of furs, merchandise, and food. Forrester took his prisoners and loot to Port Royal.[3]: 14–15 This conflict was the last fighting, between the Scots and the French, before Port Royal was returned to the French.[4]

Acadian Civil War

Blockade of St. John (1642)

Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour and Charles de Menou, Sieur d'Aulnay each had a claim of some legitimacy to be Governor of Acadia because the French Imperial bureaucracy made their appointments with an incomplete understanding of the geography of the area. LaTour had a fortified settlement at the mouth of the Saint John River while d'Aulnay's headquarters was at Port Royal some 45 miles across the Bay of Fundy. In adjoining New England, the people supported LaTour's claim since he allowed them to fish and lumber in and along the Bay of Fundy without let or hindrance while d'Aulnay aggressively sought payment for that right. Word came to LaTour that d'Aulnay was concentrating men and materials for an attack on LaTour's fort and fur trading operation at the mouth of the Saint John River. LaTour went to Boston to ask John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts Bay colony, for help. Winthrop arranged for several merchants to advance loans unofficially to LaTour for his purchase of men and material to defend the Saint John River fort from d'Aulnay's attack. For five months, the Governor of Acadia d'Aulnay who was stationed at Port Royal created a blockade of the river to defeat La Tour at his fort.[3]: 19 On 14 July 1643, La Tour arrived from Boston with four ships and a complement of 270 men to repossess Fort Sainte-Marie. After this victory, La Tour went on to attack d'Aulnay at Port Royal, Nova Scotia.[4]: 60 LaTour was unsuccessful then in catching d'Aulnay and the rivalry continued for several more years.

Siege of St. John (1645)

While La Tour was in Boston, on Easter Sunday 13 April 1645, d'Aulnay sailed across the Bay of Fundy and arrived at La Tours fort with a force of two hundred men.[4]: 61 La Tour's soldiers were led by his wife, Françoise-Marie Jacquelin, who became known as the Lioness of LaTour for her valiant defence of the fort. After a five-day battle, on 18 April, d' Aulnay offered quarter to all if Francoise-Marie were to surrender the fort. On that basis, knowing she was badly outnumbered, she capitulated and d’Aulnay had captured La Tour's Fort Stainte-Marie. d'Aulnay then reneged on his pledge of safety for the defenders and treacherously hanged the La Tour garrison while Madame de la Tour was forced to watch with a rope around her neck. Three weeks later, while still in d'Aulnay's hands, she died.[3]: 20 With the death of his wife and the loss of his fort, La Tour did not return to Acadia for the next four years, until d'Aulnay had died (1650).[4]: 61 And when he did return, he married d’Aulnay's widow to end the rivalry. He and Madame d’Aulnay had five children in the result they have hundreds of descendants living in the Canadian Maritimes today.[5]

Battle of St. John (1654)

Colonel Robert Sedgwick led one hundred New England volunteers and two hundred of Oliver Cromwell's soldiers to capture Port Royal, Nova Scotia. Prior to the battle, Sedgewick captured and plundered La Tour's fort on the Saint John River and took him prisoner.[3]: 23

King William's War

A naval battle on 14 July 1696 between New France and New England took place in the Bay of Fundy off present day Saint John, New Brunswick. English ships were sent from Boston to interrupt the supplies being taken by French ships from Quebec to the capital of Acadia, Fort Nashwaak (Fredericton, New Brunswick) on the Saint John River. The French ships of war captured one English ship, while the England frigate and a provincial tender escaped.[6]

18th century

After the Conquest of Acadia (1710), Acadians migrated from peninsula Nova Scotia to the French-occupied Saint John River. These Acadians were seen as the most resistant to British rule in the region.[7]

The only land route between Fortress Louisbourg and Quebec went from Baie Verte through Isthmus of Chignecto, along the Bay of Fundy and up the Saint John River.[8] With the establishment of Halifax, which began Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), the French recognized at once the threat it represented and that the Saint John River corridor might be used to attack Quebec City itself.[9] To protect this vital gateway, at the beginning of 1749, the French strategically constructed three forts within 18 months along the route: one at Baie Verte (Fort Gaspareaux), one at Chignecto (Fort Beausejour) and another at the mouth of the Saint John River (Fort Menagoueche). Immediately after the Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755), Robert Monckton sent a detachment to take Fort Menagoueche. French Officer De Boishebert knew that he faced a superior force so he burned the fort and retreated up the river to undertake guerrilla warfare. The destruction of Fort Menagoueche left Louisbourg as the last French fort in Acadia.[10]

British colony (1758–1867)

During the Seven Years' War, many more Acadians sought refuge from mainland Nova Scotia to the Saint John River. During the St. John River Campaign (1758), the British built Fort Frederick on the remains of Fort Menagoueche and burned every village on the river up to and including Fredericton, New Brunswick.

During the American Revolutionary War, the area was attacked by American privateers during the raid in 1775. This was followed two year later by the St. John expedition. In 1777, American forces briefly controlled Saint John after laying siege to it in 1777. In response, Major John Small personally led a force to drive out the Americans.

On June 30, 1777 under the command of Captain Hawker, four British ships with the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) arrived on the scene under the command of Major Gilfred Studholme.[11] When the 84th Regiment landed at Saint John on June 30, 1777, the Americans retreated to the woods. The 84th marched through the woods and were ambushed by the Americans. Twelve Americans and one member of the regiment were killed.[12][13] The 84th overcame Allan's force at Aukpaque (near Fredericton), some of its baggage and arms taken, but only three Americans captured.[14] Weeks later, on July 13, 1777, American privateers again attacked Saint John and were repulsed by the 84th.[13][12]

In August 1777, the Americans attacked yet again and were successful, carrying off 21 boatloads of plunder.[13][12] As a result, Major Gilfred Studholme arrived in Saint John harbour in November 1777 with orders either to repair Fort Frederick or to build a new fort. Because of the low-lying position of Fort Frederick and the damage done to it by the rebels the previous year, Studholme decided to erect a new fortification, and his 50 men, helped by local inhabitants, began the construction of Fort Howe.[15]

Incorporation of Saint John

In 1783, two settlements, Carleton and Parrtown, were established by American "Loyalists" who supported the British during the American Revolutionary War.[16] The Loyalist-dominated communities of Parrtown, on the east side of the Saint John River, and Carleton, on the west side of the Saint John River, were amalgamated by royal charter to become the City of Saint John in 1785, making it the first incorporated city in British North America (present-day Canada). To the west of Carleton was the Parish of Lancaster, and north-east of Portland were the "Lands of Simonds, Hazen and White", later called Simonds; both communities eventually amalgamated with the city in 1967.[17]

Many of those fleeing north from the American Revolution in the Thirteen Colonies were Black Loyalists, and the charter specifically excluded blacks and any whites who were not Loyalists or descendants of Loyalists, from practising a trade, selling goods, fishing in the harbour, or becoming freemen with a right to vote; these provisions stood until 1870.[18] In consequence, the town of Portland grew up north of the boundary of Saint John, around Fort Howe, where anyone could live and work freely. Portland was later amalgamated with the City of Saint John and is now thought of as the "north end."

The city's charter of 1785 established the medical quarantine station at Partridge Island, located south of the west side of the harbour.[19]: 30 Referred to as a "pest house", it was used to screen for the infectious diseases that plagued immigrant ship passengers. The quarantine station was the first landing place for many immigrants arriving at the port.

The Charter of 1785 also included a number of other provisions, to regulate local fishing rights, to establish police and fire services, trade regulation and taxation, to dedicate Navy Island for the use of the Royal Navy, and to build a lighthouse on Partridge Island.[19]: 30–33

19th century

During this war and the War of 1812, the city's location made it a probable target of attacks. This led to the construction of Fort Dufferin and Carleton Martello Tower, one of Canada's fourteen martello towers.

There were various naval battles in the Bay of Fundy fought by HMS Bream (1807) and Brunswicker, both worked out of Saint John.[20]

Irish migration

The Great Famine of Ireland (1845–1849) saw the city's largest immigrant influx occur, with the government forced to construct a quarantine station and hospital on Partridge Island at the mouth of the harbour to handle the new arrivals. These immigrants changed the character of the city and surrounding region so that in addition to its Loyalist-Protestant heritage, there was a new Irish-Catholic culture as well. Between 1845 and 1847, approximately 30,000 Irish arrived in Saint John, more than doubling the population of the city. During this period, Saint John was second only to Grosse Isle, Quebec as the busiest port of entry to Canada for Irish immigrants. The Roman Catholic population was largely impoverished and uneducated.

Saint John has often been called "Canada's Irish City". In the years between 1815, when vast industrial changes began to disrupt the old life-styles in Europe, and Canadian Confederation in 1867, when immigration of that era passed its peak, more than 150,000 immigrants from Ireland flooded into Saint John. Those who came in the earlier period were largely tradesmen, and many stayed in Saint John, becoming the backbone of its builders. But when the Great Famine raged between 1845 and 1852, huge waves of Famine refugees flooded these shores. It is estimated that between 1845 and 1847, some 30,000 arrived, more people than were living in the city at the time. In 1847, dubbed "Black 47," one of the worst years of the Famine, some 16,000 immigrants, most of them from Ireland, arrived at Partridge Island, the immigration and quarantine station at the mouth of Saint John Harbour. However, thousands of Irish were living in New Brunswick prior to these events, mainly in Saint John.

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.[21]

By 1850, the Irish Catholic community constituted Saint John's largest ethnic group. In the census of 1851, over half the heads of households in the city registered themselves as natives of Ireland. By 1871, 55 per cent of Saint John's residents were Irish natives or children of Irish-born fathers. However, the city was split with tensions between Irish Catholics and Unionist Protestants. From the 1840s onward, Sectarian riots were rampant in the city with many poor, Irish-speaking immigrants clustered at York Point.[22]

In 1967, at Reed's Point at the foot of Prince William Street, St. Patrick's Square was created to honour citizens of Irish heritage. The square overlooks Partridge Island, and a replica of the island's Celtic Cross stands in the square. Then in 1997 the park was refurbished by the city with a memorial marked by the city's St. Patrick's Society and Famine 150 which was unveiled by Hon. Mary Robinson, president of Ireland. The St. Patrick's Society of Saint John, founded in 1819, is still active today.[23]

Mid 19th century

By 1851 Saint John, with a population of 31,000, was the third largest city in British North America, after Montreal and Quebec City. In April 1854 the ship Blanche arrived in Saint John, and brought cholera to the city. Of 5,000 people stricken, 1,500 died. The periodic outbreaks centred largely in the poorer Catholic district, where people were scarcely over the effects of ship fever (typhus). The care for orphaned children became a priority.

Post-Canadian Confederation (1867–present)

Leadership was in the hands of merchants, financiers, railroad men and ship builders, who envisioned a great economic centre.[24] The city serviced a large rural hinterland in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with some 300,000 people. In the 1851–71 era, the business of the city flourished, while the rural hinterland remained stagnant.[25]

The main industry was shipbuilding – it was a major player on the world stage; the industry finally shut down in 2002. Much of the city's shipbuilding industry was concentrated on the mudflats of Courtney Bay on east side. One local shipyard built the sailing ship Marco Polo, and it was at about this time that the city became home to the world's fourth-largest accumulation of vessels.[26] Due to its location for railways and servicing the triangle trade between British North America, the Caribbean, and Britain, the city was poised to be one of Canada's leading urban centres.[25]: 333–335

Long before the Royal Military College of Canada was established in 1876, there were proposals for military colleges in Canada. After Confederation, a military school was opened in Saint John to conduct officer training for cavalry, infantry and artillery from December to May. Although the British Garrisons initially operated the school at Saint John, Canadian militia staff replaced the British regulars who were recalled from overseas station in 1870–1.[27]

A disastrous fire on June 20, 1877 destroyed a large portion of the central business district. It was the 16th recorded fire in the city and the worst ever. Starting in a warehouse it burned out of control for nine hours. The fire destroyed two-fifths of the city and left 13,000 homeless. Food, tents, clothing, and donations of money came from all over Canada, the United States, and Britain.[28][29] Saint John started rebuilding, with its community switching from building with wood to instead building with brick and stone.[30]

Trade unions

The city was a stronghold of trade unions, especially in the docks and the railways. By 1850 working class solidarity was strong among the longshoremen who handled the booming lumber trade. Labour organizations vied with merchants for control of the waterfront casual labor market. However, work-bred feelings of mutualism were often undermined by Protestant-Catholic conflicts. With the introduction of steamers, fast turnaround became even more important and the merchants could not afford job actions, so they compromised. In the World War, the longshoremen succeeded in imposing favourable new work rules and exerting partial control over hiring practices. But by 1919–20 the shipping industry regained its old authority, and hard-pressed longshoremen subsequently abandoned their class-based effort in favor of regional political activism.[31]

In July 1914, the street railway strike and riot occurred. Public opinion favoured the strikers because the company had high fares yet failed to provide quality service. Rioters overturned two streetcars, thwarted a cavalry charge, smashed windows in company offices, and poured cement on a dynamo.[32]

20th century

During the First World War, the city became a trans-shipment point for the British Empire's war effort.

At a time of rural protest in Canada from Ontario to the Prairies, the Maritime Rights Movement was a broad-based protest movement during the 1920s, demanding better treatment from Ottawa. This movement was centred in Saint John, where the city's business leaders politicized the economic crisis and solidified their economic and political leadership.[33]

Saint John's first airport was located north of the business district at Millidgeville. This location on a plateau overlooking the Kennebecasis River was a summer cottage area used by local residents to escape the coastal fog from the Bay of Fundy. Saint John Airport was developed post-war and is located in the eastern part of the city. A leading pioneer was Joseph E. Arrowsmith, the founder of New Brunswick's first passenger airline and a founder of the Saint John Flying Club. His airline was first named "Maritime Airways of Saint John" (1934), then became "Saint John Airline.'[34]

During the Second World War the port declined in importance due to the U-boat threat. Halifax's protected harbour offered improved convoy marshaling. However, manufacturing expanded considerably, notably the production of veneer wood for De Havilland Mosquito bomber aircraft. On account of the U-boat threat, additional batteries facilities were installed around the harbour.

Latter 20th century

Saint John saw major urban development between the 1950s to the 1970s.[35] Following the Second World War, plans were made to improve Saint John by city leaders. According to a 1946 study, Saint John's waterfront area was determined to be one of North America's worst slums. Several parts of the city required improvement, as indicated by another study in the mid-1950s. In the 1960s, major urban renewal projects would go underway, during which parts of the city, such as several portions of the east end facing Courtenay Bay as well as the old North End, attached to Main Street, were demolished. As less-of-interest buildings were being removed, attention was drawn towards preserving the city's heritage.[36]

An urban renewal project in the early 1970s involving a partnership between CPR along with the federal, provincial and municipal governments saw a new harbour bridge and expressway (called the Saint John Throughway) built on former railway lands. The ferry terminal for the service to Digby, Nova Scotia was also relocated from Long Wharf to a new facility on the lower West Side (see Bay Ferries Limited) as the CBD was expanded with new office buildings and downtown retail areas while historic industrial buildings were turned into shops and museums. The skyline in the city boasts office towers and historic properties.[citation needed]

In the 1970s redevelopment of the city and port, most of the port's industrial areas were scheduled to be relocated at a major new deepwater port being considered for the western part of the outer harbour at Lorneville in a major partnership between the Irving conglomerate, NB Power, CPR and the three levels of government. However, the plan fell through in favour of concentrating industrial development on the inner harbour along the mouth of the Saint John River – the very area where the waterfront redevelopment is being proposed, the Saint John Waterfront Development Partnership). Often cited in the media and by politicians as part of Saint John's redevelopment strategy, Harbour cleanup refers to the infrastructure project that will bring an end to the practice of discharging raw sewage into local waterways.[citation needed]

In 1982, Saint John introduced the Trinity Royal Heritage Conservation Area which serves to preserve its historic districts and buildings,[37] The Saint John Preservation Areas By-Law regulates exterior work done to these properties in a way that preserves the historic architecture in buildings built prior to 1915.[38] during which a 20 block area of the Uptown area was designated for historic preservation. A related development in recent years has been waterfront redevelopment for tourist and residential use. This effort increased markedly in the early first decade of the 21st century following the closure and dismantling of the Lantic Sugar refinery in the South End.[citation needed]

21st century

Saint John, having faced a several decades-long trend in population decline,[39] was overtaken in 2016 by Moncton as the most populous city in New Brunswick.[40] The city's decline in population had been supported by an aging population,[41] poverty, a lack of acceptable quality and affordable housing, and the city struggled with attracting and retaining immigrants, at the time being one of Canada's least diverse census metropolitan areas.[42] In 2018, Saint John announced a population growth strategy, primarily aimed at attracting immigrants.[43] By the following year, the city's population decline had started to reverse primarily due to immigration.[44][45][46] Saint John, as well as New Brunswick as a whole experienced a surge in population growth during COVID-19 pandemic, many of these residents migrating from western provinces such as Ontario due to better housing affordability.[47] Due to unprecedented population growth, however, Saint John started experiencing a housing crisis around 2023 due to the market not being able to keep up with the growing trend in population.[48][49]

References

- ^ Rand, Silas Tertius (1875). A First Reading Book in the Micmac Language: Comprising the Micmac Numerals, and the Names of the Different Kinds of Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Trees... Nova Scotia Printing Company.

- ^ "Geographical names approved in both English and French - Earth Sciences". Archived from the original on 2010-12-31. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- ^ a b c d e Dunn, Brenda (2004). A History of Port-Royal-Annapolis Royal, 1605-1800. Nimbus. ISBN 978-1-55109-740-4.

- ^ a b c d Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- ^ Poizner, Susan (February–March 2007). "The Lioness of Acadia". The Beaver. Archived from the original on 2012-11-22.

- ^ Murdoch, Beamish (1865). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. I. Halifax: J. Barnes. p. 218.

- ^ Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8122-0710-1.

- ^ Campbell, William Edgar (2005). The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec. Goose Lane Editions. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-86492-426-1.

- ^ Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm.

- ^ Sarty, Roger Flynn; Knight, Doug (2003). Saint John Fortifications, 1630-1956. Goose Lane Editions. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-86492-373-8.

- ^ Hannay, James (1909). The History of New Brunswick. Vol. I. Saint John, New Brunswick: John A. Bowes. p. 118.

- ^ a b c Craig, C.L. (1989). The Young Emigrants: Craigs of the Magaguadavic : a Story of the 84th Regiment, Royal Highland Emigrants, Craig Family History and the Settlement of the Magaguadavic River Area of New Brunswick. Self-published. p. 54.[better source needed]

- ^ a b c Stacy, Kim (1994). No One Harms Me With Impunity - the History, Organization and Biographies of the 84th Highland Regiment (Royal Highland Emigrants) and Young Royal Highlanders during the Revolutionary War 1775-1784 (Unpublished).[better source needed]

- ^ Gwyn, Julian (2003). Frigates and Foremasts: The North American Squadron in Nova Scotia Waters, 1745-1815. UBC Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7748-0911-5.

- ^ Godfrey, W.G. (1979). "Studholme, Gilfred". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^ "History of Saint John". 24 May 2001. Archived from the original on 2001-05-24. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ^ Schuyler, George W. (1984). Saint John: Two Hundred Years Proud. Windsor Publications (Canada). p. 122.

- ^ "Arrival of the Black Loyalists: Saint John's Black Community". Heritage Resources Saint John. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19.

- ^ a b Canada's First City, Saint John: The Charter of 1785 and Common Council Proceedings Under Mayor G.G. Ludlow, 1785-1795. Saint John, New Brunswick: Lingley. 1962.

- ^ Smith, Joshua M. (2011). Battle for the Bay: The Naval War of 1812. Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 978-0-86492-759-0.

- ^ "The Partition of Nova Scotia". Winslow Papers. University of New Brunswick. 21 June 2005. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ^ Winder, Gordon M. (Spring 2000). "Trouble in the North End: The Geography of Social Violence in Saint John 1840-1860". Acadiensis. XXIX (2): 27–57. JSTOR 30303222.

- ^ Cave, Rachel (16 March 2016). "Saint John St. Patrick's Society clings to men-only tradition". CBC New Brunswick.

- ^ Wallace, C.M. (Fall 1976). "Saint John Boosters and the Railroads in the Mid-Nineteenth Century". Acadiensis. XI (1): 71–91. JSTOR 30302585.

- ^ a b Buckner, Phillip; Reid, John G., eds. (1994). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5.

- ^ How (1993). p. 33.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[full citation needed] - ^ Preston, Richard Arthur (1969). Canada's RMC: A history of the Royal Military College. Published for the Royal Military College Club of Canada by the University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802032225.

- ^ Phillips, Doris (1977). "Nova Scotia's Aid for the Sufferers of the Great Saint John Fire (June 20th, 1877)". Nova Scotia Historical Quarterly. 7 (4): 351–366.

- ^ Rubin, Richard (27 October 2016). "In Saint John in Canada, Exploring the Legacy of the Loyalists". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "SAINT JOHN". Montreal Herald. 24 June 1889. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Babcock, Robert H. (Spring 1990). "Saint John Longshoremen During the Rise of Canada's Winter Port, 1895–1922". Labour/Le Travail. 25: 15–46. doi:10.2307/25143339. JSTOR 25143339.

- ^ Babcock, Robert H. (Spring 1982). "The Saint John Street Railwaymen's Strike and Riot, 1914". Acadiensis. XI (2): 3–27. JSTOR 30302675.

- ^ Nerbas, Don (Winter–Spring 2008). "Revisiting the Politics of Maritime Rights: Bourgeois Saint John and Regional Protest in the 1920s". Acadiensis. XXXVII (1): 110–130. JSTOR 30303121.

- ^ Wright, Harold E. (Winter 2009). "Pioneering in Maritime Air Transport". C.A.H.S.: The Journal of the Canadian Aviation Historical Society. 47 (4): 122–127.

- ^ Marquis, Greg (1 January 2010). "Uneven Renaissance: Urban Development in Saint John, 1955-1976". University of New Brunswick Saint John. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Trinity Royal - The Historic Heart of Saint John (2)". web.archive.org. 17 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Trinity Royal - The Historic Heart of Saint John (3)". web.archive.org. 17 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Trinity Royal - The Historic Heart of Saint John". web.archive.org. 10 October 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Blog, The Acadiensis (15 May 2023). "Revisiting the Shrinking City: Population, Re-industrialization and Democracy in Saint John, Part One". Acadiensis. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Scrimshaw, Mackenzie (8 February 2017). "Moncton bigger than Saint John, 2016 census confirms". CBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "The Greater Saint John Region in 2030" (PDF). New Brunswick Multicultural Council. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Marquis, Gregory (24 October 2017). "Growth Fantasies and the Shrinking City: Researching the Saint John Experience". Acadiensis. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "City of Saint John reveals plan to combat ongoing population problem". CTV Atlantic. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Smith, Connell (9 April 2019). "Immigration reverses Saint John's population decline, city data shows". CBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "'Something is changing': Saint John's population on the upswing - New Brunswick | Globalnews.ca". Global News. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ McCreadie, Danielle (9 April 2019). "Saint John Is Growing, Says Population Growth Manager". 97.3 The Wave. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Jones, Robert (21 December 2020). "Young Ontario families moving east help to reverse New Brunswick population drain". CBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Sturgeon, Nathalie (5 October 2023). "Envision Saint John proposes culture change for density to help housing crisis - New Brunswick | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Sturgeon, Nathalie (24 August 2023). "Saint John needs to double housing starts to meet population growth targets - New Brunswick | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

Further reading

- Mcgahan, Elizabeth W. (4 March 2015) [10 September 2012]. "Saint John". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.