Contents

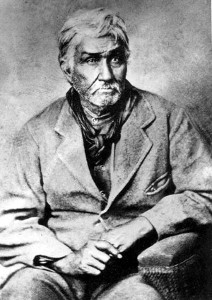

Jesse Chisholm (circa 1805 - March 4, 1868) was a Scotch-Cherokee fur trader and merchant in the American West. He is known for having scouted and developed what became known as the Chisholm Trail, later used to drive cattle from Texas to railheads in Kansas in the post-Civil War period.

Chisholm used this trail to supply his trading posts among the Native American tribes in Indian Territory, what is now western Oklahoma. He worked with Black Beaver, a Lenape guide, to develop the trail. Chisholm died before the peak period of the cattle drives from Texas to Kansas; but he was important to numerous events in Texas and Oklahoma history. He served as an interpreter for both the Republic of Texas and the United States government in treaty-making with Native American tribes.

Early life and education

Chisholm's father, Ignatius, was of Scottish descent and probably also a trader, and his mother Martha (née Rogers) was a Cherokee from the region of Great Hiwassee. As the Cherokee had matrilineal kinship, Jesse was considered to belong to his mother's people. He moved with his mother to Indian Territory during the early period when some Cherokee migrated there voluntarily from the Southeast, and grew up in Cherokee culture.

Career

In 1826, Chisholm became involved in working for a gold-seeking party, who blazed a trail and explored the region to present-day Wichita, Kansas. In 1830, he helped blaze a trail from Fort Gibson to Fort Towson. In 1834, he was a member of the Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition, who made the first contact with the southern Plains Indians on behalf of the United States federal government.[1]

In 1836, Chisholm married Eliza Edwards. They resided in the area of her father's trading post on the Little River near its confluence with the Canadian River in Indian Territory. Chisholm worked as a trader.

Fluent in thirteen Native American languages and also Spanish, Chisholm served as an interpreter and general aid in several treaties between the Republic of Texas and local Indian tribes, as well as between the United States federal government and various tribes after Texas joined the United States. This diplomatic work spanned 20 years, between 1838 and 1858.[2] During this period, he also continued in the Indian trade, trading manufactured goods for peltry and for cattle.

During the Civil War, he mostly remained neutral. Many residents of Indian Territory feared they might be massacred, either intentionally or as an accident of war if either side attempted to contend for control of the territory. Chisholm led a band of refugees to the western part of the territory. For some time, they suffered privation, as the trade had dried up during the war, as well.

At the end of the war, he settled permanently near present-day Kingfisher, Oklahoma, and again began to trade into Indian Territory. He built up what had been a military and Indian trail into a road capable of carrying heavy wagons for his goods. This road later became known as Chisholm's Trail. When the Texas-to-Kansas cattle drives started, the users of the trail renamed it the Chisholm Trail.[3]

Death and legacy

Chisholm died on March 4, 1868, at his last camp near Left Hand Spring (now Oklahoma), due to food poisoning. He was buried there.[4]

In 1974 Chisholm was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners.[5] His grave site in Blaine County is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

References

- ^ Hoig, Stan. "CHISHOLM, JESSE (ca. 1805-1868)". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Richardson, T. C. "CHISHOLM, JESSE". The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Rossel, John (February 1936). "The Chisholm Trail". Kansas Historical Quarterly. 5 (1). Kansas Historical Society: 3–14. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ "Founder of Chisholm Trail dies — This Day in History — 3/4/1868". History.com. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners".

Further reading

- "A Guide to the Jesse Chisholm Papers, 1859-1880, 1928". Texas Archival Resources Online. The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- Gaylord, Kristina (June 2011). "Chisholm Trail". Kansaspedia. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- Cushman, Ralph B. Jesse Chisholm: Trail Blazer, Sam Houston's Trouble-Shooter Friend, Kin to the Cherokee. Eakin Press. OCLC 521793565.

- Hoig, Stan (1991). Jesse Chisholm, Ambassador of the Plains. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. OCLC 22953071.

- Hoig, Stan (Winter 1988–1989). "Jesse Chisholm: Peace-maker, Trader, Forgotten Frontiersman". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. 66. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- Hoig, Stan (Summer 1989). "The Genealogy of Jesse Chisholm". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. 67. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- Taylor, T. U. (1939). Jesse Chisholm. Bandera, TX: Frontier Times. OCLC 2634774. An unverified transcription is available on line.