Contents

Cairo (/ˈkɛəroʊ/ KAIR-oh,[4] sometimes /ˈkeɪroʊ/ KAY-roh)[5] is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinois city to be surrounded by levees. It is in the river-crossed area of Southern Illinois known as "Little Egypt", for which the city is named, after Egypt's capital on the Nile. The city is coterminous with Cairo Precinct.

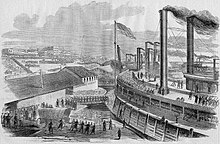

The city is located at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, some of the largest rivers in North America, and is near the Cache River complex, a Wetland of International Importance. Settlement began in earnest in the 1830s and busy river boat traffic expanded through the 1850s. Fort Defiance, a Civil War base, was located here in 1862 by Union General Ulysses S. Grant to control strategic access to the rivers, and launch and supply his successful campaigns south. Developed as a river port, Cairo was later bypassed by transportation changes away from the large expanse of low-lying land, wetland, and water, which surrounds Cairo, and due to industrial restructuring, the population peaked at 15,203 in 1920, while in the 2020 census it was 1,733.

Several blocks in the town comprise the Cairo Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). The Old Customs House is also on the NRHP. The city is part of the Cape Girardeau–Jackson, MO–IL Metropolitan Statistical Area.

The entire city was evacuated during Mississippi River floods in 2011, after the Ohio River rose higher than the 1937 flood levels, with the possibility of 15 feet of water inundating Cairo. The United States Army Corps of Engineers breached levees in the Mississippi flood zone near Cairo in Missouri to prevent flooding in Cairo and other more populous areas further downstream along both the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

History

Beginnings

The first municipal charter for Cairo and for the Bank of Cairo were issued in 1818, but without any settlement and without any depositors.[6] A second and successful effort to establish a town was made by the Cairo City and Canal Company in 1836–37, with a large levee built to encircle the site.[6] However, this effort collapsed in 1840, with few settlers remaining.[6]

Charles Dickens visited Cairo in 1842, and was unimpressed.[6] The city would serve as his prototype for the nightmare City of Eden in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit.[6] In 1846, 10,000 acres in Cairo were purchased by the trustees of the Cairo City Property Trust, a group of investors including writer John Neal[7] who planned to make it the terminus of the projected Illinois Central Railroad, which finally arrived there in 1855.

Cairo had been growing as an important river port for steamboats, which traveled all the way south to New Orleans. The city had been designated as a port of delivery by Act of Congress in 1854.

A new city charter was written in 1857, and Cairo flourished as trade with Chicago to the north spurred development. By 1860, the population exceeded 2,000.

During the Civil War, Admiral Andrew Hull Foote made Cairo the naval station for the Mississippi River Squadron on 6 September 1861. Since Cairo had no land available for base facilities, the navy yard repair shop machinery was afloat aboard wharf-boats, old steamers, tugs, flat-boats, and rafts.[8] In January 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant occupied the city, and had Fort Defiance constructed to protect the confluence. Cairo became an important Union supply base and training center for the remainder of the war.[6]

Military occupation caused much of the city's trade to be diverted by railroad to Chicago. Cairo failed to regain this important trade after the war, as more railroads converged on Chicago and it developed at a rapid pace, attracting stockyards, meat processing, and heavy industries. Instead, agriculture, lumber, and sawmills now dominated the Cairo economy.[6]

Post-war prosperity

The strategic importance of Cairo's geographic location during the Civil War sparked prosperity in the town. Several banks were founded during the war years, and the growth in banking and steamboat traffic continued after the war.

In 1869 construction began on the United States Custom House and Post Office, which was designed by Alfred B. Mullet, the Supervising Architect. The custom house was completed in 1872. It served as a custom house, post office, and United States Court. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Illinois met at the building until 1905.

From 1905 to 1942, the Custom House was used for the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Illinois. The building also housed the U.S. Circuit Court for the Eastern District of Illinois from 1905 to 1912. At the height of Cairo's prosperity, the post office in the building was the third busiest in the United States. It is one of only seven of Mullet's Victorian structures remaining in the nation, and the building has been converted for use as a museum. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[9]

After the Civil War, the city became a hub for railroad shipping in the region, which added to its economy. By 1900 several railroad lines branched from Cairo. In addition to shipping and railroads, a major industry in Cairo was the operation of ferries. Into the late 19th century, nearly 250,000 railroad cars could be ferried across the river in as little as six months. Vehicles were also ferried, as there were no automobile bridges in the area in the early 20th century. The ferry industry created numerous jobs in Cairo to handle large amounts of cargo and numerous passengers through the city.[10]

Wealthy merchants and shippers built numerous fine mansions in the 19th and early 20th century, including the Italianate Magnolia Manor, completed in 1872, and the Second Empire Riverlore Mansion, built by Capt. William P. Halliday in 1865. Across the street from the customs house, the Cairo Public Library was constructed in 1883 of Queen Anne-style architecture, finished with stained glass windows and ornate woodwork. The library was dedicated on July 19, 1884, as the A. B. Safford Memorial Library. Anna E. Safford paid for the construction of the Library and donated it to the city. These and other significant buildings are also listed on the National Register.[11]

For protection from seasonal flooding, Cairo is completely enclosed by a series of levees and flood walls, due to its low elevation between the rivers. Several buildings, including the old custom house, were originally designed to be built to a higher street level, to be at the same height as the top of the levees. That plan was scrapped as the cost of fill to raise the streets and surrounding land to that height proved to be impractical. In 1914 a large flood gate was constructed by Stupp Brothers of St. Louis, Missouri. The flood gate is known as the "Big Subway Gate", and it was designed to seal the northern levee in Cairo by closing over U.S. Highway 51. The gate weighs 80 tons, is 60 feet wide, 24 feet high, and five feet thick. With the addition of the gate, Cairo could become an island, completely sealed off from approaching flood waters.

Following the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, the levee system around Cairo was strengthened. As part of this project, the Corps of Engineers established the Birds Point-New Madrid Floodway. The Ohio River flood of 1937 brought a record water level to Cairo that crested at 59.5 feet. To protect Cairo, Corps of Engineers closed the flood gate and blew a breach in the Bird's Point levee for the first time to relieve pressure on the Cairo flood wall. Following the flood, the concrete flood wall was raised to its current height. It is designed to protect the town from flood waters up to 64 feet.[12][13][14][15]

In 1942 the federal government constructed a new U.S. Post Office and Court House in Cairo. Still growing, the city had a population approaching 15,000. The new federal court house, located at 1500 Washington, was designed by the architects Louis A. Simon and George Howe. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Illinois moved into the new court house in 1942, from the old U.S. Custom House and Post Office.

After the U.S. district court structure in Illinois was reorganized in 1978, the court house was used for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Illinois. The building remains in use by the federal courts and as the active post office for Cairo. The court house was built and is operated by the U.S. General Services Administration.[16][17]

Lynchings

Cairo's turbulent history of race relations is marked by the 1909 spectacle lynching of black resident William James. In 1900, Cairo had a population of nearly 13,000. Of that total, approximately 5,000 residents were African-American, or 38 percent. In 1900, this was an unusually high black population for a town of Cairo's size in the North. Five percent of all black residents in the state of Illinois lived here. Later in the early 20th century, Chicago became the center of black life in the state, as it was the destination of tens of thousands of migrants during the Great Migration.

The Illinois constitution of 1818 allowed for limited slavery in the salt mines and allowed current slave owners to retain their slaves. The General Assembly also passed legislation that severely curtailed the rights of free blacks residing in the state and discouraged the migration of free blacks. If a black person was unable to present proof of their freedom they could be fined \$50 or sold by the sheriff to the highest bidder. Not long after the passage of the constitution, the state's general assembly adopted a pro-slavery resolution that announced its approval of slavery in slave-holding states and at the same time condemned the formation of abolition societies within Illinois’ boundaries.[18]

Although Black people comprised a large proportion of the Cairo population, they were frequently discriminated against in jobs and housing. Race relations were strained in 1900.[19] The state passed an anti-lynching law in 1905.

On the night of November 11, 1909, two men were lynched. The first was William James, an African American accused of the murder of Anna Pelly, a young white woman killed three days earlier, although there was no physical or circumstantial evidence connecting him to the crime.[20] The second man lynched was Henry Salzner, a white man who had allegedly murdered his white wife the previous August.

James was accused of killing Pelly by choking her to death in an alley with pieces of a flour sack on the evening of November 8, 1909. Pelly's body was discovered the next morning. Police believed that James was large enough to have committed the crime, especially as there were rumors of an accomplice. James was placed in police custody on Tuesday, where he remained until Wednesday evening. No physical evidence linked him to the crime.[20] As word of the crime spread, whites in Cairo demanded an immediate trial of James, but the case was delayed by the court. The white townspeople grew infuriated by the delay in a speedy trial, and the threat of mob violence quickly developed. On November 10, Sheriff Frank E. Davis arranged to take James out of the city jail on an Illinois Central train to avoid mob violence.

One man chopped off James's head, put it on a pike, and lifted it up for the cheering crowd to see. The mob then set James's body on fire and roasted the remains while men, women, and children shouted and cheered... Some took out their pocketknives and cut off ears and fingers and broke up bones to take as gruesome souvenirs.

— Stacy Pratt McDermmot[21]

But the increasingly large mob in Cairo learned of this and seized another train, racing to catch up with the sheriff and James. Sheriff Davis' attempt to save James from the mob proved futile when the mob intercepted Davis and his prisoner. The mob returned James to Cairo and took him to the intersection of Commercial Avenue and Eighth Street. Approximately 10,000 people had gathered for a spectacle lynching as the leaders attempted to hang James from large steel arches that spanned the intersection. The rope broke and James survived the hanging, but members of the armed mob shot him more than 500 times, killing him. The mob dragged James' body to the scene of Pelly's murder. His head was cut from his body and displayed on a pole that was stuck into the ground, and his body was burned.

Hundreds of townspeople conducted a search for the alleged accomplice, Arthur Alexander. Unable to locate him and still bloodthirsty, they entered the court house jail and broke into the cell where Henry Salzner was being held. The mob hanged Salzner from a telegraph pole near the courthouse, and the crowd shot his body many times. After hanging Salzner, the mob continued searching for Alexander long into the night. Police and sheriff deputies located Alexander before the mob did, and they took him to the county jail disguised as a police officer. Some newspapers mistakenly reported that he was lynched.

The mob continued to search for Alexander, also threatening the mayor and chief of police, who were guarded in their homes by more police against the mob. Governor Charles S. Deneen of Illinois dispatched 11 companies of militia to Cairo to suppress the violence. By the time the mob discovered the next morning that Alexander was held at the jail, the soldiers had arrived and prevented further violence.[22][23][24][25]

A group of civil rights activists in Chicago hired journalist Ida B. Wells to investigate the lynchings. After the residents had calmed down, Governor Deneen enforced the 1905 anti-lynching law by dismissing Sheriff Davis for failing to protect James and Salzner.[20] Wells sided with the governor against reinstatement.

Economic decline

The slow economic decline of Cairo can be traced to local and regional changes back to the early 20th century. In 1889 the Illinois Central Railroad bridge was completed over the Ohio River, which brought about a decline in ferry business. The immediate economic impact was not severe, as the railroad traffic still was directed through Cairo, and automobile and truck traffic increased in the early 20th century.

In 1905 a second bridge was constructed across the Mississippi River at Thebes, Illinois. The effects of the second bridge were more severe, as rail traffic through Cairo was now reduced and railroad ferry operations were no longer necessary. As the steamboat industry was replaced with barges, river traffic had less reason to stop in Cairo.

In 1929, the Cairo Mississippi River Bridge was completed, linking Missouri with Illinois to the south of Cairo. In 1937 the Cairo Ohio River Bridge was completed. Completion of the two bridges ended the ferry industry in Cairo, putting many people out of work. As the town was bypassed by two bridges to the south, it also lost the benefit of motorist travel and trade between the states. Motorists cross the southern tip of Illinois between Missouri and Kentucky, completely bypassing the city of Cairo.[10][26] While the city was protected by its levees from destruction when the Ohio River rose to record heights during the 1937 flood, the city's economic decline continued.

Racial tensions and further decline

Between the 1930s and 1960s, the population in Cairo remained fairly steady; however, many jobs were gone as the shipping, railroad, and ferry industries left the city. Population decline began as workers moved to other cities.

Racial tensions rose in the late 1960s as African-Americans sought implementation of gains under new federal civil rights laws passed as a result of the Civil Rights Movement. The police, fire department, and most city jobs were still overwhelmingly dominated by whites. African-Americans were allegedly harassed by the police and unjustly targeted. On July 16, 1967, Robert Hunt, a 19-year-old black soldier home on leave, was allegedly found hanged in the Cairo police station. Police reported that Hunt had hanged himself with his T-shirt, but many members of the black community of Cairo accused the police of murder. There had been an alleged history of police discrimination and violence against black residents of the city.[27]

The death of Robert Hunt sparked aggressive protests in Cairo's black community. On July 17, 1967, a large portion of the black population in Cairo began rioting. The black rioting that erupted in 1967 was not confined to Cairo; it was part of a larger pattern of more than 40 racially motivated riots that broke out in major cities in the United States in the summer of 1967. During the night of rioting on July 17, three stores and a warehouse in Cairo were burned to the ground, and windows were broken out of numerous other buildings. The National Guard unit at Cairo was activated to respond to the violence.[28]

On July 20, 1967, one of the leaders of the violence in Cairo warned white city officials, "Cairo will look like Rome burning down" if city leaders did not meet the demands of the black groups in Cairo by Sunday, July 23, 1967. The spokesman represented approximately one hundred black residents of the Pyramid Court housing project. They demanded new job opportunities, organized recreation programs for their children, and an end to police brutality. Cairo Mayor Lee Stenzel and other city leaders met with federal and state representatives to ensure that a plan was developed to satisfy the demands by the deadline in an effort to head off any additional rioting.[29][30]

In response to the rioting, the white community in Cairo formed a citizens protection group that was deputized by the sheriff. The protection group became known as the "White Hats", because many of its 600 members began wearing white construction hats to show their membership while patrolling the streets to maintain order. In the following two years, accusations of White Hat bullying incidents in the black community began to increase. In early 1969, a few activists of the civil rights struggle formed the Cairo United Front, a civil rights organization to bringing together the local NAACP, a cooperative association, and a couple of black street gangs. The Cairo United Front was formed to organize the efforts of the black population in Cairo to counter the White Hats. The United Front formally accused the White Hats of intimidating the black community, and presented a list of seven demands to the City of Cairo. The seven demands included appointment of a black police chief, appointment of a black assistant fire chief, and an equal black-white ratio in all city jobs.[31]

Racial violence in Cairo reached a peak during summer 1969 as the Cairo United Front began leading protests and demonstrations to end segregation and draw attention to its seven demands. The protests led to a rash of violence that was stopped only when Illinois Governor Richard Ogilvie deployed National Guardsmen to restore the peace. In summer 1969, the Cairo United Front also began what became a decade-long boycott of white-owned businesses, which had generally not hired blacks as clerks or staff. The boycott encompassed virtually all the businesses in the town.

In December 1969, violence escalated again and several businesses were burned on Saturday, December 6. Early that morning, residents of the Pyramid Courts housing project opened fire on three firemen and the Chief of Police while they were responding to one of the intense fires. During the shootout, the Chief of Police and one of the firemen were shot by a high-powered rifle. Thirteen people were eventually arrested during the conflict.[32] The Cairo Chief of Police resigned the next month, stating that Cairo lacked both the legal and physical means to deal with the "guerrilla warfare tactics" that had left the town in a state of turmoil for over two years.[33]

To enforce the boycott, African-American picketing of businesses continued throughout 1970. In December, the city enacted a new city ordinance banning picketing within 20 feet of a business. Another large violent clash erupted as a result of the new city ordinance. Following the violence, the United Front called for another large rally and resumed picketing at white-owned businesses despite the new ordinance. The picketing turned violent after police heard shots fired and moved on the crowd.[34]

In 1978, the Interstate 57 bridge across the Mississippi River was opened. The interstate largely bypassed Cairo, crippling the remaining hospitality industry in the city. Cairo's hospital closed in December 1986, due to high debt and a dwindling number of patients.

Current status

With the decline in river trade, as has been the case in many other cities on the Mississippi, Cairo has suffered a marked decline in its economy and population. Its highest population was 15,203 in 1920;[35] in 2020 it had 1,733 residents, about an 89% loss of population from its peak a century earlier. The city has decreased in population for eight consecutive US census reports from 1950 to 2020.

The city faces many significant socio-economic challenges for the remaining population, including poverty, crime, issues in education, unemployment and rebuilding its tax base.

The closure of the Elmwood and McBride housing projects was announced by the federal government in 2017. In August 2017, Ben Carson, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development at the time, visited the city. Some 10 families had found new housing, but an estimated 400 people will be affected[needs update] by the closure.[36]

The community and region are working to stop abandonment of the city. They are restoring some architectural landmarks, and plan to develop heritage tourism focusing on the city's history and relationship to the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Other cities have used such strategies to attract visitors and build new businesses to their communities.

A community clinic offers medical and dental care, and several mental health services. Local media include the Cairo Citizen weekly newspaper.

Geography

Cairo is located at the confluence of the Ohio River with the Mississippi, near Mounds, Illinois. The elevation above sea level is 315 feet (96 m). The lowest point in the state of Illinois is located in Cairo at the Mississippi River.

According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Cairo has a total area of 9.11 square miles (23.59 km2), of which 6.99 square miles (18.10 km2) (or 76.72%) is land and 2.12 square miles (5.49 km2) (or 23.28%) is water.[37]

Climate

The city of Cairo has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) and has many characteristics of a city in the Upland South. Summers are warm and humid, with a daily average in July of 79 °F (26.1 °C) and temperatures reaching 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of 40 days annually. Winters are generally cool with mild periods, though extended stretches of cold can occur. Cairo's winter is typically mild by Illinois standards, as the January daily average is 34 °F (1.1 °C). Precipitation is spread relatively uniformly throughout the year. On average, Cairo's low elevation and proximity to the Mississippi and Ohio rivers prevent strong winter lows and plunging temperatures; however, during the summer months, those similar features retain heat and humidity, creating muggy conditions.

| Climate data for Cairo, Illinois (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

77 (25) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

92 (33) |

82 (28) |

79 (26) |

108 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.4 (6.3) |

48.2 (9.0) |

58.6 (14.8) |

69.9 (21.1) |

78.3 (25.7) |

85.9 (29.9) |

88.7 (31.5) |

87.8 (31.0) |

81.7 (27.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

57.9 (14.4) |

46.7 (8.2) |

68.2 (20.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 34.7 (1.5) |

38.9 (3.8) |

48.1 (8.9) |

58.7 (14.8) |

68.0 (20.0) |

76.0 (24.4) |

79.2 (26.2) |

77.6 (25.3) |

70.6 (21.4) |

59.3 (15.2) |

47.6 (8.7) |

38.4 (3.6) |

58.1 (14.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.0 (−3.3) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

37.6 (3.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

57.7 (14.3) |

66.1 (18.9) |

69.6 (20.9) |

67.5 (19.7) |

59.6 (15.3) |

47.7 (8.7) |

37.4 (3.0) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

48.0 (8.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−5 (−21) |

6 (−14) |

25 (−4) |

36 (2) |

45 (7) |

56 (13) |

50 (10) |

39 (4) |

27 (−3) |

5 (−15) |

−9 (−23) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.80 (97) |

3.88 (99) |

4.85 (123) |

5.38 (137) |

5.08 (129) |

4.37 (111) |

4.10 (104) |

3.18 (81) |

3.51 (89) |

4.14 (105) |

4.46 (113) |

4.25 (108) |

51.00 (1,295) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.1 (7.9) |

2.4 (6.1) |

1.6 (4.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.1 (2.8) |

8.6 (22) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 144.4 | 150.5 | 198.0 | 238.8 | 277.8 | 307.4 | 318.9 | 300.8 | 242.4 | 216.9 | 139.3 | 125.4 | 2,660.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 47 | 50 | 53 | 60 | 63 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 65 | 62 | 46 | 42 | 58 |

| Source 1: NOAA (1991–2020 temperature and precipitation normals, sun 1961–1987)[38][39] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Western Regional Climate Center (snow normals 1948–2012),[40] The Weather Channel (extremes) [41] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 242 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,188 | 804.1% | |

| 1870 | 6,267 | 186.4% | |

| 1880 | 9,011 | 43.8% | |

| 1890 | 10,324 | 14.6% | |

| 1900 | 12,566 | 21.7% | |

| 1910 | 14,548 | 15.8% | |

| 1920 | 15,203 | 4.5% | |

| 1930 | 13,532 | −11.0% | |

| 1940 | 14,407 | 6.5% | |

| 1950 | 12,123 | −15.9% | |

| 1960 | 9,348 | −22.9% | |

| 1970 | 6,277 | −32.9% | |

| 1980 | 5,931 | −5.5% | |

| 1990 | 4,846 | −18.3% | |

| 2000 | 3,632 | −25.1% | |

| 2010 | 2,831 | −22.1% | |

| 2020 | 1,733 | −38.8% | |

| Decennial US Census | |||

2020 census

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 434 | 25.04% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,193 | 68.84% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 5 | 0.29% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 5 | 0.29% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 76 | 4.39% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 20 | 1.15% |

| Total | 1,733 |

As of the 2020 census[43] there were 1,733 people, 828 households, and 377 families residing in the city. The population density was 190.29 inhabitants per square mile (73.47/km2). There were 1,036 housing units at an average density of 113.76 per square mile (43.92/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 25.33% White, 68.96% African American, 0.40% Native American, 0.63% from other races, and 4.67% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.15% of the population.

There were 828 households, out of which 18.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.07% were married couples living together, 20.29% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.47% were non-families. 52.29% of all households were made up of individuals, and 23.55% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.42 and the average family size was 2.16.

The city's age distribution consisted of 21.7% under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 16.9% from 25 to 44, 28.8% from 45 to 64, and 23.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 47.4 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $27,661, and the median income for a family was $31,280. Males had a median income of $14,464 versus $21,188 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,661. About 32.9% of families and 36.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 72.1% of those under age 18 and 14.2% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 2,831 people, 1,268 households, and 677 families residing in the city. There were 1,599 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 69.6% Black or African American, 27.9% White, less than 0.1% Native American, less than 0.1% Asian, less than 0.1% Pacific Islander, less than 0.1% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were less than 0.1% of the population.

There were 1,268 households, of which 26.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 21.2% were married couples living together, 28.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.6% were non-families. 43.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 3.00.

The distribution of the population by age was 31.6% 19 or under, 6.3% from 20 to 24, 19.2% from 25 to 44, 26.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.6% 65 or older. The median age was 36.9 years.

The median income for a household in the city was $16,682, and the median income for a family was $31,507. Males working full-time, year-round had a median income of $37,750 versus $21,917 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,461. About 33.0% of families and 44.2% of the population were living below the poverty line, including 71.7% of those under the age of 18 and 20.6% of those ages 65 and older.

2000 census

As of the census[44] of 2000, there were 3,632 people, 1,561 households, and 900 families residing in the city. The population density was 515.1 inhabitants per square mile (198.9/km2). There were 1,885 housing units at an average density of 103.2 per km2 (267.3 per sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 35.93% white, 61.70% black or African American, 0.08% Native American, 0.72% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.36% from other races, and 1.18% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.74% of the population.

There were 1,561 households, out of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.3% were married couples living together, 25.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.3% were non-families. 39.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 3.08.

The distribution of the population by age was 30.4% under 18, 8.1% from 18 to 24, 22.0% from 25 to 44, 21.6% from 45 to 64, and 17.9% who were 65 or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 79.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 70.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,607, and the median income for a family was $28,242. Males had a median income of $28,798 versus $18,125 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,220. About 27.1% of families and 33.5% of the population were living below the poverty line, including 47.0% of those under the age of 18 and 20.9% of those ages 65 and older.

Education

The city is served by Cairo Community Unit School District 1. Based on census estimates, the Cairo school district has the highest percentage in Illinois of children in poverty, 60.6%. This is the fifteenth highest percentage of any city in the United States.[45] The district has one elementary school, Emerson Elementary School. Middle and high school students attend Cairo Junior/Senior High School. Bennett Elementary School closed in 2010.[46]

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Belleville formerly operated St. Joseph Grade School.[47] It was previously K-12,[48] but by 2001 it had only elementary grades.[47] Enrollment was over 130 during the 1976–1977 school year. This figure dropped to 63 in 2000, and then 25, including 7 Catholic students, in the 2002–2003 school year. The school closed in 2003.[48]

Shawnee Community College opened an extension center in Cairo in January 2019.[49]

Government

Cairo is in Illinois's 12th congressional district and is represented in Congress by Republican Mike Bost. In 2020, 42.60 percent of Alexander County voters cast ballots for Democratic candidate and the 46th President Joe Biden.[50]

Transportation

Amtrak's Chicago–New Orleans City of New Orleans served Cairo until October 25, 1987; since then, its closest stops to Cairo are Carbondale, Illinois, 53 miles (85 km) to the north, and Fulton, Kentucky, 43 miles (69 km) to the south.[51]

Major highways include:

Cairo's location on a spit of land that lies between the Mississippi and Ohio rivers made overlapping US 60 and 62 briefly through Illinois more practical than directly connecting Missouri and Kentucky.

Cairo Regional Airport provides general aviation service to the city.

The closest airports with regular service are Barkley Regional Airport and Cape Girardeau Regional Airport. The airports are approximately 23 miles and 26 miles away, respectively.

Landmarks and points of interest

Magnolia Manor is a postbellum manor, built by the Cairo businessman Charles A. Galigher in 1869. It is a 14-room red brick house which features double walls intended to keep out the city's famous dampness with their ten-inch airspaces. Inside the home are many original, 19th-century furnishings. It has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since December 17, 1969.[52] The house is operated as a Victorian period historic house museum by the Cairo Historical Association.

Other points of interest include:

- Fort Defiance Park

- Gem Theatre[53]

- The Hewer, a 1902 public sculpture by George Gray Barnard

- Cairo Custom House & Post Office[54]

- The Riverlore[55]

- A. B. Safford Memorial Library[56]

In popular culture

- Filmmakers Jacob Cartwright and Nick Jordan's feature-length documentary Between Two Rivers (2012)[57] is about the social, economic and environmental problems faced by Cairo.

- Cairo was the original destination for Huck and Jim in Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, as they planned to paddle up the Ohio River to obtain freedom for Jim. They drifted past Cairo by mistake and ended up in the slave state of Arkansas instead. Twain also noted Cairo in his non-fiction Life on the Mississippi.[58]

- Charles Dickens visited Cairo in 1842 and was unimpressed with what he saw as a disease-ridden backwater. It became the model for the town of Eden in his 1843–44 novel Martin Chuzzlewit.[59]

- The musician Stace England produced a concept music CD called Greetings From Cairo, Illinois (2005), inspired by the city's turbulent history.[60]

- In the Disney Channel series So Weird episode 58 season 3 episode 19, an Egyptology museum in the town of Cairo, Illinois, turns out to be inhabited by a reanimated mummy.[61]

- The town serves as a plot point in Neil Gaiman's 2001 novel American Gods.[62]

- In the John Wayne movie "True Grit", Matti Ross asks Rooster what he did after the war. His answer was he robbed a pay master for a grub stake, then a little bank in New Mexico. After that he moved to Cairo, Illinois and opened an eatery called the Grass Frog.

Sports

- Cairo had its own minor-league baseball team (variously known as the Egyptians, Champions, Giants and Dodgers) in the Kentucky–Illinois–Tennessee League in 1903–06, 1911–14, 1922–24 and 1946–50.

- The St. Louis Cardinals of the National League held their annual spring training camp in Cairo from 1943 to 1945, due to travel restrictions imposed by Major League Baseball during World War II.[63]

- The town of Cairo is known for its love of basketball. In 2017, the Cairo Pilots high school basketball team came close to their first state championship, finishing 23–6 for the season. Finishing within four games of a state championship was especially noteworthy given the school's size. Enrollment in fall 2017 was only 97 students.[64]

Notable people

See also

- Illinois in the Civil War

- List of cities and towns along the Ohio River

- Steamboats of the Mississippi

- USS Cairo

References

Notes

- ^ Hevern. Southeast Missourian https://web.archive.org/web/20110519114653/http://www.semissourian.com/story/1726712.html. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cairo, Illinois

- ^ Brown, Donald E.; Schooley, Frank E. (1957). Pronunciation Guide for Illinois Place Names. University of Illinois.

- ^ McClelland, Edward (2019). "A Downstate Illinois Dictionary." Chicago Magazine.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Cairo | Illinois, United States". October 25, 2023.

- ^ Cairo City Property (Cairo, Ill.) (1858). The past, present and future of the city of Cairo, in North America. Portland [Me.]: Printed by B. Thurston. p. 99. OCLC 13619400. OL 271527M.

- ^ Miller, Francis Trevelyan (1957). The Photographic History of The Civil War. Vol. Six: The Navies. New York: Castle Books. pp. 213–215.

- ^ "US Customs House and Post Office, Cairo, IL"[permanent dead link], Northern Illinois University Library

- ^ a b "Cairo, Illinois". Lib.niu.edu. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ John McMurray Lansden. A history of the city of Cairo, Illinois. 1910. pp 153–154, 231–234

- ^ [1] Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Cairo Flood Wall Holds as Ohio River Rises". PJ Star. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Over Under and Through the Ohio's Assault on Cairo". St. Louis Beacon. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Coast Guard and Army Corps of Engineers Assist Residents in Midwest Flood Zone". Coast Guard. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "General Services Administration (GSA) Inventory of Owned and Leased Properties". Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Post Office and Courthouse – Cairo, Illinois". Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "African Americans in Illinois". Historic Reservation Division.

- ^ "1909: Will James, "the Froggie", lynched in Cairo". November 11, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c " 'An Outrageous Proceeding': A Northern Lynching and Enforcement of Anti-Lynching Legislation in Illinois, 1905–1910", Journal of Negro History, 1999, via JSTOR

- ^ McDermott, Stacy Pratt (1999). "'An Outrageous Proceeding': A Northern Lynching and the Enforcement of Anti-Lynching Legislation in Illinois, 1905-1910". The Journal of Negro History. 84 (1): 61–78. doi:10.2307/2649083. JSTOR 2649083. S2CID 150209743.

- ^ John M. Lansden and Clyde C Walton. A History of the City of Cairo, Illinois. 2009, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Niederkorn, William S. (November 12, 2009). "One Lynching in Cairo, Ill.; Then, Another". The New York Times.

- ^ "Lynching of a White Man." The Straits Times. December 18, 1909, p. 15.

- ^ "Soldiers Awe Mob; Negro Taken Away; Cairo People, Who Lynched Two, Jeer When Intended Victim Is Escorted to Train. Sheriff Seeks Evidence No Other Steps Taken to Prosecute Mob Leaders -- Mayor and Others Defend the Mob's Acts" (PDF). The New York Times. November 13, 1909.

- ^ [2] Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Let my people Go". Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Alert Guard After Racial Riots in Cairo". Chicago Tribune. July 18, 1967. p. 11.

- ^ "Scattered Race Riot Recurring". The Free-Lance Star. July 21, 1967. p. 3.

- ^ "Cairo Seeks to Head Off More Riots". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. July 22, 1967. p. 1.

- ^ "Races: War in Little Egypt". Time. September 26, 1969.

- ^ "2 Businesses Burn Saturday Morning". The Southeast Missourian. December 8, 1969. p. 4.

- ^ "Racial Tension Prompts Police Chief to Quit". Meriden Journal. January 2, 1970. p. 8.

- ^ "More Picketing Called Following Cairo, Ill Riot". The Lewiston Daily. December 7, 1970. p. 4.

- ^ Sanborn, "Cairo, IL", University of Michigan

- ^ Siegler, Kurt (August 9, 2017). "Carson Promises To Help Residents Of Housing Projects His Department Is Shutting Down". National Public Radio. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "Station: Cairo 3N, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ "Cairo/WSO City IL Climate Normals 1961–1987". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ "General Climate Summary Tables". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "Climate Statistics for Cairo, Illinois". Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "If you're poor, you have to work harder... nothing is fair", Chicago Sun-Times, January 10, 2008 Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bennett Elementary to Close in Cairo", KFVS 12, March 4, 2010 Archived May 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Schools". Roman Catholic Diocese of Belleville. August 18, 2001. Archived from the original on August 18, 2001. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

CAIRO St. Joseph Grade School 421 Cross Street Cairo, IL 62914

- ^ a b Quirin, Liz (August 1, 2003). "End of an Era as Catholic School Closed at St. Joseph's in Cairo". The Messenger. Belleville, Illinois. pp. 9, 17. - Clipping of first and of second page at Newspapers.com.

- ^ Parker, Molly (January 8, 2019). "Shawnee Community College plants roots in Cairo with opening of new extension center". The Southern Illinoisan. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ "Illinois presidential results". Politico. Illinois. January 6, 2021. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Craig (2006). Amtrak in the Heartland. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34705-3., p. 105

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Gem Theatre in Cairo, IL". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "customhouse". Southernmost Illinois History. Archived from the original on August 8, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Riverlore, Cairo IL, Pilot Light 2000 Historic Page". Pilotlight2000.com. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Cairo Public Library, Cairo IL, Pilot Light 2000 Historic Page". Pilotlight2000.com. May 5, 1985. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Between Two Rivers". Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Mark Twain. "Life on the Mississippi 173-6 (1883)". Lhup.edu. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Martin Chuzzlewit – as discussed in Cairo, Illinois, United States". Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Jones, Rachel (January 29, 2006). "Singer Evokes Turbulent History of Cairo, Ill". National Public Radio. Retrieved September 19, 2009.

England, 43, grew up on a Wabash River farm in central Illinois. Cairo, pronounced "Care-O", didn't became a creative inspiration for him until he started writing music and playing the guitar in the late 1980s.

- ^ Anderson, George (October 25, 2018). "epguides.com presents So Weird a Brief Episode Guide by George Fergus". Epguides.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (February 7, 2023). American Gods. Dark Horse Comics. ISBN 978-1-5067-3499-6. OCLC 1369840573.

- ^ "Why the Cardinals chose Cairo, Ill., for spring training". RetroSimba. March 2, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Dougherty, Jesse; Hutson, Boswell (May 2, 2018). "Ben Carson called this small Illinois town a 'dying community.' Its people, and basketball, are hanging on". Washington Post. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

Further reading

Published in the 19th century

- John Mason Peck (1839). "City of Cairo and Canal Company". The Traveller's Directory for Illinois. New York: J.H. Colton. OCLC 29129415. OL 24162626M.

- "Cairo". Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1858 and 1859. Chicago, Ill: George W. Hawes. 1858. OCLC 4757260. OL 24140361M.

- Cairo City Property (Cairo, Ill.) (1858), The past, present and future of the city of Cairo, in North America, Portland [Me.]: Printed by B. Thurston, OCLC 13619400, OL 271527M

- "Cairo". Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory, for the Years 1864-5. Chicago: J.C.W. Bailey. 1864. OCLC 6867103. OL 7082742M.

- "Part 1: Cairo". History of Alexander, Union and Pulaski Counties, Illinois. Chicago, Ill: O.L. Baskin & Co. 1883. OCLC 8695008. OL 6608394M.

Published in the 20th century

External links

- Between Two Rivers, a feature-length documentary about Cairo

- Cairo, Illinois at Abandoned

- History of Cairo by David Mascitelli

- Abandoned Town of Cairo, Illinois, at Atlas Obscura