Contents

Buck Colbert Franklin (May 6, 1879 – September 24, 1960) was an African American lawyer best known for defending survivors of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre.

Early life and education

Buck Colbert Franklin was born on May 6, 1879, near Homer, in would later become Pontotoc County, Oklahoma.[1] His father, David Franklin, was a Black man who had escaped from slavery and fought for the Union Army in 1864.[2] His mother, Millie Colbert Franklin, was one-fourth Choctaw and had been raised in that nation's traditional culture.[2] Millie and David were married in 1856 and moved from Mississippi to a 300-acre farm near Homer in the Indian Territory, on communal land of the Chickasaw Nation.[2] Buck was the seventh of the couple's ten children, and was named for his grandfather, who had purchased his own freedom.[2] Millie died in 1886 after a trip to Tuskahoma to prove her Choctaw citizenship.[2] David was a successful rancher who used his wealth to build up his community.[2]

Franklin's childhood was shaped by his chores on the ranch, and by age eleven he could ride horses, hunt deer, and cook for the family.[2] In 1890 his father brought him along on a business trip to Guthrie, where they met territorial governor George Washington Steele and young Franklin saw prominent African American lawyers and businessmen at work.[2] He was a successful athlete and student at Dawes Academy boarding school near Springer, Oklahoma; after graduating from Dawes, he was accepted at Roger Williams University in Nashville.[2]

Shortly after his father's death in 1900, Franklin followed his Dawes Academy teacher and mentor, John Hope, to attend the more prestigious Atlanta Baptist College (later Morehouse College).[2] Franklin met his classmate Mollie Lee Parker, and they married in 1903.[2] Mollie and Buck both pursued their studies while managing a large homestead, but when an illness killed the ranch's hogs, they lost nearly all their wealth and got jobs as teachers.[2]

Early career

The young couple settled on a smaller homestead in Ardmore, Oklahoma.[2] While working as a teacher, Franklin apprenticed with Black lawyers in Ardmore and studied to become a lawyer through a correspondence course from the Sprague School of Law in Detroit.[3] He was admitted to the Oklahoma Bar in December 1907.[3] He practiced law in Ardmore, then in 1912 moved the family to the African American town Rentiesville, Oklahoma.[2] Franklin established a newspaper, the Rentiesville News, and served as postmaster general for the town.[2] Much of his legal work involved defending the land and mineral rights of the Native American and freedmen communities.[2]

Work and life in Tulsa

In 1921

Franklin moved to Tulsa in early 1921, leaving his wife and youngest children behind in Rentiesville until he could save a nest egg of money.[2] He established a law practice with I.H. Spears and T.O. Chappelle at 107 1/2 North Greenwood Avenue, in the prosperous Greenwood District referred to as "Black Wall Street."[3][4] He survived three days of violence led by white mobs now known as the Tulsa race massacre, although he was marched at gunpoint to the Tulsa Convention Hall and imprisoned for several days, and his office was one of the many buildings destroyed.[3] He would later write about what he saw during those days, including families fleeing burning buildings and three men shot and killed.[2]

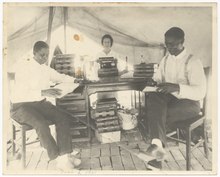

In the weeks after the Greenwood District was destroyed, the mayor and city commission worked to plan new commercial development in the area which would move Black residents and their businesses out of the downtown area.[2] The new plan would require new construction in the Greenwood area be constructed from fireproof materials such as brick, which the struggling residents could not afford.[5] Franklin, Spears, and Chappelle set up a makeshift tent as their office to provide legal support to the victims of the violence.[2] The team filed Tulsa County Case No. 15730, Joe Lockard v. T.D. Evans, et al., against Mayor T. D. Evans, the city commission, and others in the city government, arguing that the city did not have the right to prohibit the Black property owners from rebuilding on their own land.[2] An appeal by the city was rejected in September 1921 by a three-judge panel of Tulsa County judges who found that the city sought to deny the property rights of Greenwood's residents without due process.[2] The Greenwood community would go on to rebuild. Franklin and Spears also worked to process insurance claims for Greenwood residents, but these were unsuccessful.[3]

After 1921

Franklin's wife Mollie and their two younger children joined him in Tulsa in 1925; she started the first daycare for children of working mothers in North Tulsa.[2] Franklin continued to practice law; one of his cases reached the Oklahoma Supreme Court, a defamation lawsuit against World Publishing Co., the publisher of the newspaper Tulsa World.[2] In another notable case, he successfully argued that an all-white jury was discriminatory in a criminal case with a Black defendant.[5] He became a Senior Member of the Oklahoma Bar Association in 1959.[2]

After he suffered a stroke in 1956 which paralyzed the right side of his body, he endeavored to finish his autobiography with the help of his son John Hope.[2] He died in Tulsa on September 24, 1960.[3]

Legacy

The Franklins had four children together: Mozella Denslow, Buck Colbert Jr., Anne Harriet, and John Hope.[2] John Hope Franklin would go on to become a prominent historian and intellectual.[1]

In 2021, the University of Tulsa College of Law established the new Buck Colbert Franklin Legal Clinic, offering free legal services to residents of the Greenwood neighborhood.[6] The law school also hosts The Buck Colbert Franklin Memorial Civil Rights Lecture every year.[7]

My Life and An Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin was edited by his son John and grandson John Whittington Franklin and published in 1997.[8] The book includes details about Franklin's childhood in the Indian Territory, recollections of events such as the Tulsa race massacre, and reflections on race and the law.[8]

References

- ^ a b Yared, E. (April 2, 2016). "Buck Colbert Franklin (1879–1960)". BlackPast. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "The Victory of Greenwood: B.C. Franklin". The Victory of Greenwood. October 20, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "B.C. Franklin". Tulsa Historical Society & Museum. October 5, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Hannibal B. (March 1, 2021). "Greenwood: Rebirth". TulsaPeople Magazine. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ a b DelCour, Julie (January 17, 2016). "The legacy of B.C. Franklin". Tulsa World. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "TU Law to launch Buck Colbert Franklin Legal Clinic". University of Tulsa College of Law. February 3, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ "The Buck Colbert Franklin Memorial Civil Rights Lecture". Mabee Legal Information Center Digital Commons. University of Tulsa College of Law. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b "My Life and An Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin". LSU Press. Louisiana State University. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

External links

- "My Life and an Era: Buck Colbert Franklin" 40-minute video featuring John Hope Franklin and John Whittington Franklin discussing the book they co-edited (2001)