Contents

Staunton Military Academy was a private all-male military school located in Staunton, Virginia. Founded in 1884, the academy closed in 1976.[1] The school was highly regarded for its academic and military programs, and many notable American political and military leaders are graduates, including Sen. Barry Goldwater, the 1964 Republican presidential candidate, and his son, Rep. Barry Goldwater Jr., 1960's folk singer Phil Ochs, and John Dean, a White House Counsel who was a central figure in the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s.

A museum dedicated to the school's history is located on its former campus, now part of Mary Baldwin University.[1] Throughout its history, the academy was referred to by students, faculty, and Staunton residents simply by its initials, SMA.

History

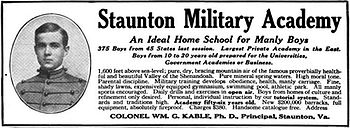

The Staunton Male Academy was founded in 1884 by William H. Kable, a native of Virginia in the region that became West Virginia following the Civil War.[2] Kable served the Confederacy during the war and was injured during the Battle of Gettysburg, and when the war ended began a career in education. After teaching briefly in rural Virginia, Kable enrolled at the University of Virginia to resume studies he had begun before the war. He graduated with a Master of Arts in 1868 and briefly started a school outside Staunton, Virginia but left teaching to tend to his family's farm near Charlestown, West Virginia. Kable married during this period and had his first son in 1872. Around this time, he joined the Charlestown Academy, a private school, as Principal, a position he held for 12 years. Near the end of his tenure at Charlestown, in May 1884, Kable sold 13 acres of his farm and purchased a house and four-acre property in Staunton with the intention of starting his own school.[3]

Troubled times

On September 2, 1884, the Staunton Male Academy opened with 50 students, including boarders who lived in the Kable residence. Classes were held in a frame building Kable had constructed on the property. After four years of successful operation, Kable added a wood frame barracks, acquired additional land, and adopted a military format, changing the school's name to Staunton Military Academy. During the summer of 1888, Kable's brother-in-law and business manager W.W. Gibbs went on a tour of the South and recruited more than 40 students. The academy started its 1888–89 session with a total enrollment of 117 cadets and a faculty of 11 instructors.

Around this time, a depression struck the country, and over the next decade enrollment at the new academy dwindled, falling to 50 in 1892. Unable to satisfy his creditors, Kable turned over control of the school to a trustee, and the next year he was forced to sell his assets at public auction, first the school's furnishings and equipment and then his land, house, and school buildings. Kable incorporated Staunton Military Academy which offered to buy the school's contents and was high bidder for the properties, having secured bonds that were to be satisfied in annual payments. Kable spent the next ten years paying off his remaining debts, which were finally settled in 1903. However, during this period enrollment continued to decline, sinking to 30 in 1896 and a low of 15 in 1900.

Recovery years

Kable's son William G. Kable was completing his studies at the academy as the troubles were just beginning. After graduating with honors in 1890, he went off to work for a year in Cincinnati, completed business college in Baltimore, taught for two years at the academy, and then worked for several major firms in New York City. The younger Kable finally returned to Staunton in 1898 to become a Mathematics and Languages instructor and was promoted to Commandant in 1900 with responsibility for managing the academy's operations. He was joined by another key figure in the school's development, Thomas Russell. A graduate of The Citadel military college in South Carolina, Russell had distinguished himself as a cadet and after graduation became Commandant at Horner Military Academy in North Carolina. In 1904, he was invited to come to Staunton as Headmaster.[4] Meanwhile, Captain Kable, as the father was known (he had been a Captain and a Quartermaster during the Civil War), served as President.

The new Commandant began expanding the school soon after taking over. He built a three-story wooden frame Mess Hall in 1901 with cadet rooms on the upper floors and added a five-story frame barracks in 1904. Enrollment soared over the first years of the new century with 270 cadets signed up for the start of the 1904 academic session. Then, on November 25, 1904, the day after Thanksgiving, a fire broke out in the new barracks. By morning, three of the academy's main structures were leveled, including the new barracks, the school's original barracks, and its classroom building. Only the Mess Hall building and Kable residence were spared.

Fortunately, no students were seriously injured, many of them awoken by Captain Kable himself. The town of Staunton responded to the tragedy admirably. Cadets were offered temporary housing, and the YMCA provided accommodations for classes. Meanwhile, the Kables went right to work rebuilding the school.

Expansion period

In March 1905, construction began on a combination barracks and classroom facility. Within six months the building was completed, in time for the start of the 1905 school year that September. Eventually named South Barracks, the three-story brick fortress-like structure stood on the top of the hill at the southern edge of the academy grounds overlooking Mary Baldwin College. The arched entranceway at the north end led to an open quadrangle surrounded by cadet rooms, classrooms, and study hall on the first floor and open galleries with cadet rooms and suspended walkways on the two upper floors. In all, the barracks accommodated over 100 cadet rooms, 3 laboratories, and 19 classrooms, including a large instruction hall on the second floor.

The academy flourished under the younger Kable over the next 15 years. Captain Kable died in 1912, at which point his son became President. That same year, the academy's plaza, which was used several times each day for cadet formations, was covered with asphalt, giving the assembly area the name it would be known by for the next six decades, "The Asphalt." In 1913, a new 500-seat Mess Hall was completed, and a building known as the Natatorium was erected to house a new swimming pool. In 1917, while the U.S. was becoming involved in World War I on the side of the Allies, SMA joined the Army's Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps (JROTC) program, an affiliation that would last for nearly a half-century. The next year, a Junior School was added for 6th through 8th grades with the only wooden barracks to be built since the disastrous fire of 1904.

Finally, North Barracks was constructed in 1919. With six stories and a smokestack at the rear rising another three stories above the roof, the building was the tallest ever built in Staunton. Four three-story columns graced its entrance, topped by a triangular gable with a large clock overlooking The Asphalt. The bottom floor, which was two stories tall, housed a gymnasium that could be used as a 1,600-seat assembly hall. The second floor included a mezzanine and the entrance to the school's armory, an underground storage facility in the front of the barracks.

The entrance from The Asphalt led to the building's third floor, which housed the school library, a post office, cadet social room, classrooms, and a laboratory. As with South Barracks, the building had an open quadrangle with cadet rooms around the perimeter and suspended walkways on the three upper floors. With the addition of North Barracks and its 55 cadet rooms, SMA opened its 1919-20 academic year with 650 students, a record that would stand until the mid-1960s.

Good times and bad

William G. Kable died in 1920, and as the academy's sole shareholder, he bequeathed ownership to his widow and their children.[5] Thomas Russell, who was promoted to President,[4] completed Kable's expansion plans during the mid-1920s, adding a wall around the Kable Field parade grounds, a two-story Guard House at the center of the South Barracks quadrangle, and Memorial Hall on the campus's north end. The latter structure, which was three stories tall, housed the Mathematics and Foreign Language departments, classrooms, faculty apartments, a gymnasium, and three large recreation rooms.

The last major building to be built on the SMA campus for the next 30-plus years was Kable Hall, in 1932. Located between Memorial Hall and North Barracks, the five-story structure included a new swimming pool on its ground floor, 54 cadet rooms on the three floors above the pool, and a rifle range on the fifth floor. The building, dedicated in honor of the academy's founder and his son, marked the end of the school's expansion, though various improvements would continue over the ensuing decades.

With the nation in the throes of the Great Depression, SMA's enrollment plummeted, and only 264 cadets enrolled the year Kable Hall was completed. Russell died the next year, 1933. With a new president in place and a new member installed on the academy's Board of Trustees, one of the board's original trustees was accused of an impropriety that occurred during the course of Russell's tenure.

In 1937, William G. Kable II brought a court suit alleging that William C. Rowland had issued improper commission payments to Russell over the 13-year period of his presidency. Rowland was forced to resign and ordered to pay $116,000 plus interest to the academy. Kable also charged Gilpin Willson, the new President, with breaching his fiduciary duty as a trustee in connection with an uncollected loan, resulting in a judgment of $150 plus 20% of the premiums for a life insurance policy taken out on Russell's behalf. In addition, Willson was held responsible for half of the commissions paid to Russell.[5] Finally, with the death of the new trustee in 1940, William G. Kable's widow was able to replace most of the board, giving her and her son complete control of the institution.

Cadet life

For the next quarter of a century, SMA earned a national reputation for its academic standards and the quality of its Junior ROTC program. Each day began for cadets with reveille on The Asphalt followed by breakfast in the Mess Hall. Students then attended classes until mid-afternoon with a break for lunch. After school, cadets participated in drills, practiced sports, and enjoyed free time. Following dinner, the evenings held more free time, sweep detail, a study period, and at the end of the day, taps.

On weekends, the routine changed. Saturdays included periodic military inspections and town leave, while Sundays featured church services and occasional parades. Other cadet activities included the academy's elite honor guard and drill team, The Howie Rifles; weekend varsity and junior varsity sports, notably varsity football; periodic dances; a military ball each spring; and alumni events twice annually. The school year would be capped with graduation ceremonies in late May, highlighted by a formal review of the corps on Kable Field led by the next year's First Captain, the highest ranking cadet.

The academy's demise

During the 1960s and 1970s, the unpopularity of the Vietnam War created an anti-military sentiment that eroded enrollments at military academies across the U.S. Contributing to the difficulties faced by military schools, particularly in the South, was the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Under the act, programs receiving federal funds were required to racially integrate. SMA chose not to do this, instead giving up federal funds by dropping its JROTC program and did not admit Black Students though the school continued to admit Asian and Hispanic students. SMA hoped to attract an influx of students who were withdrawing from the now-racially integrated public schools. The enrollments never materialized and instead, students gravitated toward non-military private schools.[6][7] JROTC was reestablished in a few years and continued until 1976's closure, when during that year the Corps received an unprecedented 100% score during the Annual Federal Inspection, held every spring by Army Command, and known as "GI Weekend".

The enrollment at Staunton peaked during the 1966-67 school year, reaching a historic high of 665 cadets. By 1972, enrollment fell to about 250, climbing back into the 300s the following year, then entering a final decline to under 200 by 1976. Accordingly, the academy's finances began to decline. Its last profitable school year was 1969-70, which ended with a net of $69,000 for the Kable family. The next year, 1970–71, the owners experienced a loss of $98,000, followed by a deficit of $132,000 a year later.[8]

Faced with the prospect of bankruptcy, the Kables elected to sell the academy. The new owner, Layne Leoffler, changed SMA's charter to non-profit status when he took over the school in 1973.[8][9] The following year, Loeffler undertook cost-cutting measures, including a reduction in athletic scholarships and the closing of North Barracks.[10] He also fully integrated the school admitting the first Black students in the fall of 1973. However, his introduction of aggressive religious practices, peculiar staff and management changes, and reactions to accidental fires in South Barracks and Kable Hall proved too much. The deteriorating situation, combined with management problems, forced the academy to close in 1976. Mary Baldwin University, then a women's college and SMA's longtime neighbor, bought the property for $1.1 million in a bankruptcy sale.[11]

Staunton Military Academy today

Today, eight of the buildings in which SMA cadets lived and learned survive as part of the Mary Baldwin campus. The SMA Mess Hall sign still hangs over the entrance to the building, now the university's Student Activities Center. The military legacy of the academy's grounds continues through the Virginia Women's Institute for Leadership (VWIL) at Mary Baldwin, the only all-women's corps of cadets in the world.

In 2001, a joint SMA-VWIL museum opened in the academy's former supply room at 227 Kable Street in Staunton. Additionally, the alumni association has endowed four scholarships to keep the school's legacy alive: SMA Leadership Scholarship, Henry Scholarship Honoring SMA, Henry SMA Legacy Scholarship for VWIL cadets, and SMA-John Deal Education Scholarship for a Florida State University student.

In April of each year an SMA all-class reunion is held in Staunton. Events include an "Old Boys" parade on Friday afternoon in conjunction with VWIL on the former SMA parade field and a banquet on Saturday night.

Academy buildings and campus

The SMA campus covered 60 acres, which were purchased by the Kable family as 30 separate parcels from 1884-1946. Following are the buildings that were part of the academy over its 92-year history, including those that have survived and are now owned by Mary Baldwin University.[12][13]

- Kable House: built 1873, added to Virginia Landmarks Register, December 19, 1978, and National Register of Historic Places, June 19, 1979 (Ref. # 79003299), current Student Life & Career Development Department, Mary Baldwin

- Kable Field (parade ground): purchased 1884, current Physical Activities Center, Mary Baldwin

- Classroom Building: built 1884, destroyed by fire 1904

- First Cadet Barracks: built 1887, destroyed by fire 1904

- The Asphalt (assembly grounds): built 1887, current parking lot, Mary Baldwin

- Original Mess Hall: built 1903, destroyed by fire 1933

- Second Cadet Barracks: built 1904, destroyed by fire 1904

- Original Laundry Building: built c. 1905, demolished 1918 (replaced by North Barracks)

- South Barracks: built 1905, demolished 1979

- Mess Hall: built 1913, current Student Activities Center, Mary Baldwin

- Natatorium (swimming pool): built 1913, demolished for Kable Hall 1931

- Superintendent's Quarters: built as Commandant's House 1916, current President's House, Mary Baldwin

- Junior School: built 1918-21, demolished 1966 (replaced by Tullidge Hall)

- North Barracks: built 1919, demolished 1982

- Central Heating Plant and Laundry: built 1919, current Drama Department Costume Shop, Mary Baldwin

- Mathematics Building: built 1921, destroyed by fire 1933

- West Barracks: built as Work Shop 1931, current Physical Plant Offices and Shops, Mary Baldwin

- Kable Hall: built 1932, current Kable Residence Hall, Mary Baldwin

- Memorial Hall (classroom building): built 1925, current Deming Fine Arts Center, Mary Baldwin

- Wieland Memorial Gate: built 1947

- Supply Room: built 1947, current Staunton Military and Virginia Women's Institute for Leadership Museum, opened 2001

- Tullidge Hall: built 1966, current Tullidge Residence Hall, Mary Baldwin

Faculty

Notable faculty included:

- Newton D. R. Allen (died 1927), American politician[14]

- Thomas D. Howie, "the Major of St. Lo"[15]

- Alexander Patch, commander of the Seventh Army 1944-1945 [16]

- Colonel Robert H. Wease, Professor of Government[17]

Extracurricular activities

Staunton Military Academy sports teams played teams from other prep schools, as well as college freshman and varsity teams. The academy also had a group known as the Howie Rifles, a nationally known drill team.

Notable alumni

- Ed Beard (1960), NFL San Francisco 49ers, 1965–72

- Ken Beck, defensive tackle for the Green Bay Packers in 1959-60

- Samuel Beer (1929), political scientist

- Winton M. Blount (1938), United States Postmaster General 1969-71

- Bruce Crump, drummer of Molly Hatchet

- E. Jocob Crull (1877), Montana State Representative and colonel who was Jennette Rankin's (first female member of the U.S. Congress) chief primary rival

- John Dean (1957), White House Counsel 1970-73 [18]

- Walter E. Foran, member of the New Jersey Legislature 1969-86

- Robert T. Frederick (1924), World War II combat commander

- Frank L. Gailer Jr. (1941), World War II flying ace[19]

- Barry Goldwater (1928),[20] five-term US Senator from Arizona (1953–65, 1969–87)

- Barry Goldwater Jr. (1957), US Representative from California 1969-83

- Frank Gorrell (1941) Lt. Gov. of State of Tennessee; Speaker of the state senate; football player for Vanderbilt University

- Ricardo Martinelli, President of the Republic of Panama 2009-14

- David McCampbell (1928), World War II Navy "Ace of Aces" and Medal of Honor recipient

- Phil Ochs (1958), folk singer and songwriter

- Edward C. Peter II (1947), U.S. Army lieutenant general[21]

- Chuck Pfarrer (1975), ex-Navy SEAL, novelist, screenwriter

- Bill Quinlan (1952), NFL player for nine seasons

- Johnny Ramone, guitarist and founding member of The Ramones (attended only for ninth grade)

- Lennie Rosenbluth (1953), college and NBA basketball player

- Richard P. Ross Jr., decorated brigadier general in the Marine Corps during World War II

- Bob Savage (1942), Philadelphia Athletics pitcher

- John F. Seiberling (1937), US Representative from Ohio 1971-87

References

- ^ a b Barnabi, Rebecca (February 12, 2016), "Staunton museum preserves military academy's history", The News Virginian, p. 1, retrieved July 30, 2018

- ^ "One of America's Most Distinguished Military Academies". sma-alumni.org. Staunton Military Academy Alumni Foundation. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Gregory P., SMA Historian. "SMA History Project: The Road to Staunton". Staunton Military Academy History Project. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b History of Virginia. Vol. 5. American Historical Society. 1924. p. 431. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Supreme Court of Virginia: Willson v. Kable, anylaw.com, June 8, 1941, retrieved August 17, 2021

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Trousdale, William B. (2016). Military High Schools in America. Routledge. ISBN 9781315424637.

- ^ "SMA Drops Army ROTC" (PDF), The Kablegram, p. 1, May 28, 1965, archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2018, retrieved July 29, 2018

- ^ a b Income Statements and Balance Sheets 1969 thru 1975 dated November 25, 1975 - United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia in Proceedings for Arrangement 75-236 (H)

- ^ "S.M.A. Ownership Transferred" (PDF), The Kablegram, p. 1, December 12, 1972, archived (PDF) from the original on July 29, 2018, retrieved July 29, 2018

- ^ Robertson, Gregory P., SMA Historian. "SMA History Project: The End of an Era, The Passing of a Dream". smahistory.com. Staunton Military Academy History Project. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Contract of Purchase dated November 16, 1976 & Order of Sale of Real Estate to Mary Baldwin College dated December 8, 1976 - United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia in Proceedings for Arrangement 75-236 (H)

- ^ Robertson, Gregory P., SMA Historian. "SMA History Project: Buildings and Grounds". Staunton Military Academy History Project. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mary Baldwin Main Campus Map" (PDF). Mary Baldwin University. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ "Newton D. R. Allen". The Evening Sun. 1927-02-03. p. 36. Retrieved 2023-03-22 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Service held in honor of Major Howie who gave his life liberating French town of St. Lo", The Daily Progress, August 9, 2017, archived from the original on August 9, 2017, retrieved August 2, 2018

- ^ "Tactician's Dream". Time Magazine. 1944-08-28. Archived from the original on 2009-03-07. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

Later he taught machine-gun operation at Fort Benning, taught military science at Staunton Military Academy, attended the Command and General Staff School, was graduated from the Army War College. In 1933 he wrote: "Now I am back at Staunton where I hope they will forget all about me." They didn't. After Pearl Harbor, Sandy Patch was sent to the French island of New Caledonia in the Pacific.

- ^ Robert H. Wease 1932-2019, legacy.com, 2019, retrieved August 17, 2021

- ^ "How John Dean Came Center Stage". Time Magazine. 1973-06-25. Archived from the original on 2008-12-14. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

At Virginia's Staunton Military Academy, he is best remembered not as an All-America backstroker but as having been extraordinarily willing to sacrifice himself for others.

- ^ "Brigadier General Frank L. Gailer Jr". United States Air Force. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ Adam Clymer (1998-05-29). "Barry Goldwater, Conservative and Individualist, Dies at 89". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-03-07. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

As a teen-ager, he failed half his courses in his first year in high school in Phoenix. His parents packed him off to Staunton Military Academy in Virginia, where he thrived. After graduating in 1928, he entered the University of Arizona at Tucson.

- ^ "Obituary, Edward C. Peter II". Legacy.com. Chicago, IL: Legacy.com, Inc. November 19, 2008. Retrieved December 11, 2022 – via The Washington Post, Savannah Morning News.