Contents

The Wood Green ricin plot was an alleged bioterrorism plot to attack the London Underground with ricin poison. The Metropolitan Police Service arrested six suspects on 5 January 2003,[1][2] with one more arrested two days later.

Within two days, the Biological Weapon Identification Group at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory in Porton Down were sure that there was no trace of ricin on any of the articles that were found. This fact was initially misreported to other government departments as well as to the public, who only became aware of this in 2005.[3] Reporting restrictions were in place before the public's perceptions could be corrected.[4][5]

The only conviction directly relating to terrorism was of Kamel Bourgass, sentenced to 17 years imprisonment for conspiring "together with other persons unknown to commit public nuisance by the use of poisons and/or explosives to cause disruption, fear or injury" on the basis of five pages of his hand-written notes on how to make ricin, cyanide and botulinum.[6] Bourgass had already been sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of detective Stephen Oake, whom he stabbed to death during his arrest in Manchester. Bourgass also stabbed three other police officers in that incident; they all survived. All other suspects were either released without charge, acquitted, or had their trials abandoned.[4] Bourgass had attended meetings of Al-Muhajiroun leading up to the plot.[7]

Public reaction

Prime Minister Tony Blair referred to the case in a speech shortly after the arrests.[8][better source needed]

Physicians throughout the United Kingdom were warned to watch for signs that patients had been poisoned by ricin,[2][9] and the public health director for London urged the public not to be alarmed following some media reports. Britain's largest circulation tabloid newspaper, The Sun, reported the discovery of a "factory of death",[10] and other newspapers warned on their front pages "250,000 of us could have died", "Poison gang on the loose" and "Killer with no antidote".[11][12]

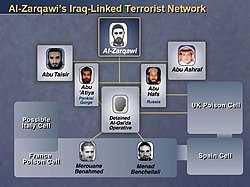

The fact that no ricin had been found was known to some government departments very early on, but this information was not revealed to the public until after Bourgass's trial two years later, although in the interim it was cited in support of further terrorism laws. The "UK poison cell" featured in a slide used with the US Secretary of State Colin Powell's 5 February 2003 speech to the UN to build the case for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. As late as February 2006, Chancellor Gordon Brown described it as a significant terrorism plot spanning 26 countries.[13]

Timeline of arrests and announcements

- 5 January 2003 – Police raided a flat above a pharmacy at 352 High Road, Wood Green, north London, and arrested six men on suspicion of manufacturing ricin intended for use in a terrorist poison attack on the London Underground.[1][14]

- 7 January — A seventh man was arrested.[15]

- 12 January — Five men and a woman were arrested in the Bournemouth area for terrorism involving ricin,[16] but released without charge several days later.[17]

- 14 January — Three men were arrested in Crumpsall, north Manchester, in a raid to detain a man who had been certified under part 4 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001.[18] Detective Constable Stephen Oake died after being stabbed eight times with a kitchen knife by Kamel Bourgass who was also there.[19]

- 20 January — Police raided and closed the Finsbury Park mosque for several days as part of the investigation. Seven men were arrested; another was arrested in London the next day.[20]

- 5 February – Colin Powell, the United States Secretary of State, referred to those arrested as the "UK poison cell" of a global terrorist network in making a case for military intervention in Iraq to the United Nations Security Council.[21] A week later he testified to the Committee on International Relations of the United States House of Representatives that this ricin had originated in Iraq,[22] though this was disputed immediately.[23]

- 11 March — The Home Secretary issued control orders against ten terrorist suspects just released from detention connecting them to the ricin plot, even though it was alleged to have occurred while they were in custody. Letters of apology were sent two weeks later explaining that it was a "clerical error", but that they were still terrorist suspects.[24]

- 21 March — Two vials falsely testing positive as ricin are found in a train station in Paris.[25] These were said to be connected to an attack on the Russian embassy,[26] until further tests proved that they were jars of wheat germ.[27]

- 15 September 2005 — Two[28] of the men tried with Bourgass were arrested in 2005 to face deportation on for national security reasons.[29] Two of the jurors who found them not guilty at the ricin trial expressed their sense of anger and betrayal at this.[28] One of them 'Y', who in 1997 and 1998 was sentenced in absentia to death and life imprisonment for terrorist offences by an Algerian court, appealed his deportation in 2006.[30]

Trials

On 30 June 2004, Kamel Bourgass was convicted for the murder of DC Stephen Oake during his arrest and was jailed for life with a minimum tariff of 22 years. During periods of his imprisonment, Bourgass has been placed in segregation after he was accused by prison authorities of involvement in attacks on other prisoners and attempts to force other inmates to convert to Islam.[31]

A second trial of five defendants, including Bourgass, for conspiracy to commit murder and other charges, began in September and lasted until 8 April 2005. Bourgass alone was convicted and sentenced to 17 years for conspiring to cause a public nuisance by "plotting to spread ricin and other poisons on the UK's streets".[32] Mouloud Sihali and David Khalef were convicted of possessing false passports.[33]

On 12 April 2005 the jury was dismissed after failing to reach a verdict on the charge of conspiring to commit murder, and a third trial of four further defendants was abandoned before it started.[32]

There was a blanket ban on media reporting until the trials ended.[5]

In October 2005, Eliza Manningham-Buller, the Director General of MI5, revealed that the evidence which uncovered the so-called ricin plot came from Mohamed Meguerba, a man who jumped bail and fled to Algeria where he was detained.[34] There was press speculation that Meguerba had been tortured.[34]

In the investigation spurred by the plot, dozens of houses raided and over 100 people were arrested.[8]

Criticisms

| Events leading up to the Iraq War |

|---|

|

|

On 13 April 2005, Jon Silverman, a legal affairs correspondent for the BBC wrote:

[I]s this case... notable for the way in which criminal investigations are shamelessly exploited for political purposes by governments in the UK and United States, whether to justify the invasion of Iraq or the introduction of new legislation to restrict civil liberties?

A key unexplained issue is why the Porton Down laboratory, which analysed the material and equipment seized from a flat in Wood Green, said that a residue of ricin had been found when it had not.[35]

On 11 April 2005, George Smith, of GlobalSecurity.org summed up:

It is no longer a surprise when one finds that many claims from the alleged best of American government intelligence in the war on terror are bogus. It is still dismaying, though, to see intelligence derived from materials submitted in the alleged trial of the "UK poison cell" that is so patently rotten. Who was informing Colin Powell on the nonsense before his date with the UN Security Council?

There was no UK poison cell linked to al Qaida or Muhamad al Zarqawi. There was no ricin with which to poison London, only notes and 22 castor seeds . There was no one who even knew how to purify ricin.[3]

On 17 August 2006, former British ambassador to Uzbekistan Craig Murray summed up:

I spoke at the annual Stop the War conference a couple of months ago [and] referred to the famous ricin plot... It was alleged that a flat in North London inhabited by Muslims was a "Ricin" factory, manufacturing the deadly toxin which could kill "hundreds of thousands of people". Police tipped off the authorities that traces of ricin had been discovered. In the end, all those accused were found not guilty by the court. The "traces of ricin" were revealed to be the atmospheric norm.

The "intelligence" on that plot had been extracted under torture in Algeria. Another police tip-off to the media was that the intelligence said that the ricin had been stored in plastic jars, and they had indeed found plastic jars containing a suspicious substance. It turned out the containers in question were two Brylcreem tubs. What was in them? In the first, paper clips. In the second, Brylcreem.[36]

The Wood Green conspiracy allegations were also depicted critically in the 2007 documentary Taking Liberties.

In 2023, Julian Hayes, a barrister who represented one of the acquitted defendants, said the plot investigation stemmed from Algerian intelligence given to Britain about an alleged UK mass poisoning plot, from information obtained from Mohamed Meguerber which Hayes believes was obtained through torture.[8]

See also

- Murder of Stephen Oake

- 2003 ricin letters

- List of terrorist incidents in the United Kingdom

- Casey Cutler

References

- ^ a b "Terror police find deadly poison". BBC. 7 January 2003. Archived from the original on 30 May 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ a b Dr Pat Troop — Deputy Chief Medical Officer (7 January 2003). "Concern over ricin poison in the environment". Department of Health (CEM/CMO/2003/1). Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ^ a b Smith, George (11 April 2005). "UK Terror Trial Finds No Terror: Not guilty of conspiracy to poison London with ricin". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ a b Summers, Chris (13 April 2005). "Questions over ricin conspiracy". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 January 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ a b "Terror trial had blanket news ban". BBC. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (14 April 2005). "The ricin ring that never was". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Gateway to Terror: Anjem Choudary and the Al-Muhajiroun Network" (PDF). Hope not Hate. November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Mortimer, Josiah (30 March 2023). "Ricin and the Red Tops: How a Made-Up Terror Plot Helped the Media Build the Case for the Iraq War". Byline Times. London. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Dr Pat Troop — Deputy Chief Medical Officer (9 January 2003). "Interim guidelines for health professionals on the response to suspected ricin exposure". Department of Health (CEM/CMO/2003/2). Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Seventh Man Arrested in London Ricin Case". Fox News. Associated Press. 8 January 2003. Archived from the original on 1 March 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "More Plotters With Ricin May Be on the Loose, London Police Say". Fox News. Associated Press. 8 January 2003. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "The sober truth about ricin". The Argus. 9 January 2003. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ^ Gordon Brown (13 February 2006). "Full text of Gordon Brown's speech to the Royal United Services Institute in London". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Burke, Jason; Bright, Martin (12 January 2003). "Britain faces fresh peril from the 'clean-skinned' terrorists". The Observer. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Police question seven over ricin find". BBC. 10 January 2003. Archived from the original on 6 December 2003. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Six questioned in ricin investigation". BBC. 14 January 2003. Archived from the original on 16 December 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Five released after terror raids". BBC. 14 January 2003. Archived from the original on 18 January 2003. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Lord Filkin (16 January 2003). "Death of Detective Constable Stephen Oake: Inquiry". House of Lords. Hansard. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Mystery still surrounds killer". BBC. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 November 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Mosque closed to worshippers". BBC. 24 January 2003. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Colin Powell (5 February 2003). "Al-Zarqawi's Iraq-Linked Terrorist Network". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Colin Powell (14 February 2006). "The President's international affairs budget request for fiscal year 2004; hearing before the Committee on International Relations; 108th Congress". House of Representatives. Archived from the original on 26 October 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- ^ "Europe skeptical of Iraq-ricin link". CNN. 12 February 2006. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2006.

- ^ "Apology over control orders error". BBC. 16 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 March 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Ricin found in Paris". BBC. 21 March 2003. Archived from the original on 14 April 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Ricin 'linked to militants'". BBC. 21 March 2003. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Paris 'ricin' find is harmless". BBC. 11 April 2003. Archived from the original on 20 June 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ a b "Our verdict was ignored: Two jurors from last year's ricin trial explain why they feel betrayed by a decision to deport men they found not guilty". The Guardian. 18 September 2006. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Algerian detainees 'face torture'". BBC. 16 September 2005. Archived from the original on 24 December 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Questions over terror informant". BBC. 24 May 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Terrorists Bourgass and Hussain denied court challenge". BBC News. 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Killer jailed over poison plot". BBC. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "The ricin case timeline". BBC. 13 April 2005. Archived from the original on 5 March 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ a b "MI5's 'torture' evidence revealed". BBC. 21 October 2005. Archived from the original on 23 October 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Silverman, Jon (13 April 2005). "Comment: Questions unanswered". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 January 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Hitting a nerve". Craig Murray. 17 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

Further reading

- Lawrence Archer; Fiona Bawdon; Michael Mansfield (2010). Ricin!: The Inside Story of the Terror Plot That Never Was. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745329277.

External links

- Dispatches: Spinning Terror The 'ricin plot'

- List of suspects involved from the BBC

- Ricin case timeline from the BBC

- Critical view from The Register

- GlobalSecurity.org report assesses the entire case and all the allegations