Contents

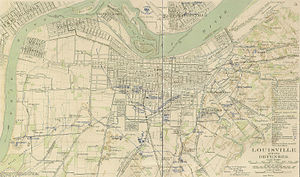

Louisville's fortifications for the American Civil War were designed to protect Louisville, Kentucky, as it was an important supply station for the Union's fight in the western theater of the war. They were typically named for fallen Union officers; usually those that served in the Army of the Ohio. The inspiration for building the forts came in October 1862, when Confederate forces engaged in their largest attack in Kentucky, only to be halted at the Battle of Perryville. Construction began in 1863, going at a slow pace until Confederate forces marched on Nashville, Tennessee, in the autumn of 1864. This caused General Hugh Ewing to demand from the city to force both military convicts and local "loafers" to help build the fortifications. Due to military engineers being needed on the front lines, the fortifications in Louisville were designed by civilian assistant engineers, as were the ones in Cincinnati, Ohio. Louisville was never endangered, so the guns never fired, save for salutes.[1]

Description

Unlike earlier fortifications, which were quickly constructed of stone masonry and timber, these forts were designed for heavy artillery fire. Also, it was decided that a five-mile (8 km) radius from the city would not adequately defend the city from artillery fire. As a result, newer fortifications would not use any pre-existing fortifications.[2]

They typically held a minimum of 50 artillerists and 200 infantrymen, with four to six cannon. Twelve batteries were to back up eleven forts in a 10 and a half mile arc around the city, relying on the Ohio River to protect the city's northern flank. They were placed in prominent positions, where they could engage in a cross-fire of opposing forces. The forts' lengths were between 550 and 700 feet (210 m), with walls fifteen to thirty feet thick, and six to eight feet high. 200 rounds for each gun were available in the forts.[2][3]

Forts

These forts were:

- Fort Clark: Located on the corner of 36th and Magnolia Streets. It was named for Lt. Col. Merwin Clark of the 183rd Ohio Infantry who died at the Battle of Franklin in November 1864.[4]

- Fort Elster: Near Bellaire, Emerald, and Vernon Avenues, between Brownsboro Road and Frankfort Avenue, where Beargrass Creek empties into the Ohio River. It was named for George R. Elstner, a Lieutenant Colonel of the 50th Ohio Infantry who died in Georgia in August 1864.[3]

- Fort Engle: Corner of Arlington Ave. and Spring Street. It was named for Captain Archibald H. Engle of the 13th U.S. Infantry, who died in Georgia in May 1864.[3]

- Fort Hill: On the hill between St. Louis Cemetery and Goddard Avenue, on what is now Castlewood Avenue. It was named for George W. Hill, a captain in the 12th Kentucky Infantry who died in Atlanta, Georgia, in August 1864.[3]

- Fort Horton: Where Merriwether and Shelby Streets meet. It was named for M.C. Horton, a captain of the 104th Ohio Infantry who died in Georgia in May 1864.[3]

- Fort Karnash: Between 26th and 28th Sts. on Wilson Avenue. It was named for Julius E. Karnash, a Second Lieutenant of the 35th Missouri Infantry who died in Atlanta, Georgia, in August 1864.[4]

- Fort McPherson: in the area of Preston Street, by the old Shepherdsville Turnpike and Louisville and Nashville Railroad, south of the old city limits. Fort Street, in Louisville, Kentucky pinpoints the location on today's maps. It was named for the Major General, James B. McPherson, who died in Atlanta, Georgia, in July 1864. It was the largest of fortifications for Louisville. It was also the first to be built. It typically held 100 artillerists and 500 infantry, but could hold upwards to a thousand soldiers. Its Parrott rifle, actually an artillery cannon, could shoot a 100-pounder shell five miles (8 km) away. It was complemented with ten additional artillery pieces. It also featured a caponier battery, built in the October 1864.[2][5][6]

- Fort Philpot: located by Algonquin Parkway and present-day Seventh Street Road (then the Louisville and Nashville Turnpike Road). It was named for J. D. Philpot, a captain for the 103rd Ohio Infantry who died in the Battle of Resaca in May 1864.[4]

- Fort Saint Clair Morton: on a small hill at corner of where 16th and Hill Streets would be if they intersected, it guarded what is now Dixie Highway (then Salt River Turnpike Road). Named for Major James St. Clair Morton of the Corps of Engineers, who died in the Second Battle of Petersburg in June 1864.[4]

- Fort Saunders: within Cave Hill Cemetery, named after E.D. Saunders of the A.A.G. Volunteers, who died in Georgia in June 1864.[3]

- Fort Southworth: On Paddy's Run, by the north side of a bend 1/4 mile from the Ohio River. It was named for A. J. Southworth, who died in Atlanta, Georgia, in August 1864. It was the westernmost of the fortifications and covered 19,000 square feet (1,800 m2) in total. Its construction began on August 1, 1864, and was paid for both by Louisville and by the federal government.[6][7]

Batteries

Only two of the proposed twelve batteries were constructed:

- Battery Camp: Located between Fort Hill and Fort Saunders, on the corner of present-day Baxter and Rufer Avenue. It was named for Edgar Camp, a captain of the 107th Illinois Infantry who fell at the Battle of Lost Mountain.[4]

- Battery Gallup: centered between Fort Clark and Fort Southworth on part of the old State Fairgrounds, it was named for A.G. Gallup of the 13th Kentucky Infantry who died in September 1864 in Georgia.

After the war

By March 31, 1865, the eleven forts were mostly completed. On May 1, progress of the fortifications had ended, as the majority of Confederate forces had already surrendered. Forty-four to sixty-six artillery pieces were to be used at the forts, but only twenty-two had been installed by the time construction was halted.[4]

None of these protections for Louisville have survived into the 21st century.

See also

- Camp Joe Holt

- Fort DeWolf

- Fort Duffield

- Louisville in the American Civil War

- Taylor Barracks (Kentucky)

References

- ^ Civil War Engineering and Navigation www.usace.army.mil/usace-docs/misc/un22/c-7.pdf pg. 109-113

- ^ a b c Civil War Engineering and Navigation pg.111

- ^ a b c d e f Kleber, John E. Encyclopedia of Louisville. (University Press of Kentucky). pg.196.

- ^ a b c d e f Kleber 197

- ^ Field, Ron. American Civil War Fortifications (2): Land And Field Fortifications (Osprey Publishing) pg. 21.

- ^ a b Kleber 196, 197

- ^ KY:Historical Society - Historical Marker Database - Search for Markers