Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Background

-

2Beginning of Appomattox Campaign

-

3Opposing forces

-

4Battle

-

4.1V Corps and Mackenzie's division join Sheridan

-

4.2Pickett withdraws to Five Forks

-

4.3Disposition of Confederate force

-

4.4Pursuit of Pickett's force

-

4.5Grant sends Sheridan permission to relieve Warren

-

4.6Sheridan's plan of attack; V Corps called up

-

4.7Mackenzie disperses Roberts's cavalry

-

4.8Pickett, Fitzhugh Lee away at shad bake

-

4.9Ayres starts V Corps attack; Sheridan at front

-

4.10Warren searches for Griffin, Crawford

-

4.11Griffin joins the main attack

-

4.12Second Confederate left flank line breached

-

4.13Sheridan orders Ayres, Griffin, Chamberlain forward

-

4.14Crawford moves forward; Warren searches again

-

4.15Pickett learns of attack; rides back to battle

-

4.16Third Confederate left flank formed, collapses

-

4.17Corse, Rooney Lee cover Confederate withdrawal

-

4.18Union cavalry attack

-

4.19Five Forks taken; Pegram killed

-

4.20Miles blocks White Oak Road

-

4.21Custer held off; pursues Fitzhugh Lee

-

4.22Warren leads a final charge

-

4.23Casualties

-

-

5Aftermath

-

5.1Confederate survivors move toward railroad

-

5.2Sheridan relieves Warren of command

-

5.3Porter reports victory to Grant; Grant orders general assault

-

5.4Grant sends Confederate flags to Lincoln

-

5.5Lee learns of defeat, sends troops west to railroad

-

5.6Grant sends Miles division to Sheridan; Sheridan's plan

-

5.7Medal of Honor recipients

-

-

6Footnotes

-

7Notes

-

8References

-

9Further reading

-

10External links

The Battle of Five Forks was fought on April 1, 1865, southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, around the road junction of Five Forks, Dinwiddie County, at the end of the Siege of Petersburg, near the conclusion of the American Civil War.

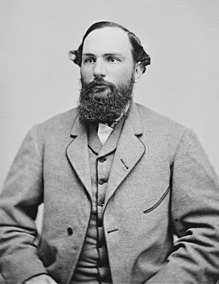

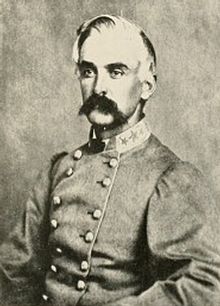

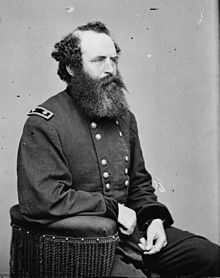

The Union Army commanded by Major General Philip Sheridan defeated a Confederate force from the Army of Northern Virginia commanded by Major General George Pickett. The Union force inflicted over 1,000 casualties on the Confederates and took up to 4,000 prisoners[notes 1] while seizing Five Forks, the key to control of the South Side Railroad, a vital supply line and evacuation route.

After the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House (March 31) at about 10:00 pm, V Corps infantry began to arrive near the battlefield to reinforce Sheridan's cavalry. Pickett's orders from his commander General Robert E. Lee were to defend Five Forks "at all hazards" because of its strategic importance.

At about 1:00 pm, Sheridan pinned down the front and right flank of the Confederate line with small arms fire, while the massed V Corps of infantry, commanded by Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, attacked the left flank soon afterwards. Owing to an acoustic shadow in the woods, Pickett and cavalry commander Major General Fitzhugh Lee did not hear the opening stage of the battle, and their subordinates could not find them. Although Union infantry could not exploit the enemy's confusion, owing to lack of reconnaissance, they were able to roll up the Confederate line by chance, helped by Sheridan's personal encouragement. After the battle, Sheridan controversially relieved Warren of command of V Corps, largely due to private enmity.[notes 2] Meanwhile, the Union held Five Forks and the road to the South Side Railroad, causing General Lee to abandon Petersburg and Richmond, and begin his final retreat.

Background

Military situation

Siege of Petersburg

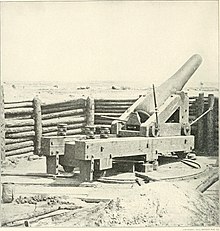

The 292-day Richmond–Petersburg Campaign (Siege of Petersburg) began when two corps of the Union Army of the Potomac, which were unobserved when leaving Cold Harbor at the end of the Overland Campaign, combined with the Union Army of the James outside Petersburg, but failed to seize the city from a small force of Confederate defenders at the Second Battle of Petersburg on June 15–18, 1864.[4] Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant then had to conduct a campaign of trench warfare and attrition in which the Union forces tried to wear down the smaller Confederate Army, destroy or cut off sources of supply and supply lines to Petersburg and Richmond and extend the defensive lines which the outnumbered and declining Confederate force had to defend to the breaking point.[5][6] The Confederates were able to defend Richmond and the important railroad and supply center of Petersburg, Virginia, 23 miles (37 km) south of Richmond for over nine months against a larger force by adopting a defensive strategy and skillfully using trenches and field fortifications.[7][8]

After the Battle of Hatcher's Run on February 5–7, 1865, extended the lines another 4 miles (6.4 km), Lee had few reserves after manning the lengthened defenses.[9] Lee knew that his defenses would soon become unsustainable and the best chance to continue the war was for part or all of his army to leave the Richmond and Petersburg lines, obtain food and supplies at Danville, Virginia, or possibly Lynchburg, Virginia, and join General Joseph E. Johnston's force opposing Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's army in North Carolina. If the Confederates could quickly defeat Sherman, they might turn back to oppose Grant before he could combine his forces with Sherman's.[10][11][12][13] Lee began preparations for the movement and informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate States Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge of his conclusions and plan.[14][15][16]

Under pressure from President Jefferson Davis to maintain the defenses of Richmond, and in any event unable to move effectively over muddy roads with poorly fed animals in winter, General Lee accepted a plan by Major General John B. Gordon to launch an attack on Union Fort Stedman designed to break Union lines east of Petersburg or at least compel Grant to shorten the Union Army lines.[17] If this were accomplished, Lee would have a better chance to shorten the Confederate lines and send a substantial force, or nearly his whole army, to help Johnston.[18][19]

Gordon's surprise attack on Fort Stedman in the pre-dawn hours of March 25, 1865, captured the fort, three adjacent batteries and over 500 prisoners while killing and wounding about 500 more Union soldiers. The Union IX Corps under Major General John G. Parke promptly counterattacked. The IX Corps recaptured the fort and batteries, forced the Confederates to return to their lines and in places to give up their advance picket line. The IX Corps inflicted about 4,000 casualties, including about 1,000 captured, which the Confederates could ill afford.[17][20]

Gains by the II Corps and VI Corps on the afternoon of March 25, at the Battle of Jones's Farm, capturing Confederate picket lines near Armstrong's Mill and extending the left end of the Union line about 0.25 miles (0.40 km) closer to the Confederate fortifications, put the VI Corps within about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) of the Confederate line.[21][22] After the Confederate defeats at Fort Stedman and Jones's Farm, Lee knew that Grant soon would move against the only remaining Confederate supply lines to Petersburg, the South Side Railroad and the Boydton Plank Road, and possibly cut off all routes of retreat from Richmond and Petersburg.[23][24][25]

Beginning of Appomattox Campaign

Grant's orders

On March 24, 1865, the day before the Confederate attack on Fort Stedman, Grant already had planned for an offensive to begin March 29, 1865.[26] The objectives were to draw the Confederates out into a battle where they might be defeated and, if the Confederates held their lines, to cut the remaining road and railroad supply and communication routes between areas of the Confederacy still under Confederate control and Petersburg and Richmond. The Battle of Fort Stedman had no effect on his plans.[27] The Union Army lost no ground due to the attack, did not need to contract their lines and suffered casualties that were a small percentage of their force.[28][29]

Grant ordered Major General Edward Ord to move part of the Army of the James from the lines near Richmond to fill in the line to be vacated by the II Corps under Major General Andrew A. Humphreys at the southwest end of the Petersburg line before that corps moved to the west. This freed two corps of Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac for offensive action against Lee's flank and railroad supply lines: Major General Andrew A. Humphrey's II Corps and the V Corps commanded by Major General Gouverneur K. Warren.[30][31] Grant ordered the two infantry corps, along with Major General Philip Sheridan's cavalry corps, still designated the Army of the Shenandoah, under Sheridan's command, to move west. Sheridan's cavalry consisted of two divisions commanded by Brigadier General Thomas Devin and Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer but under the overall command of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Wesley Merritt, as an unofficial corps commander, and the division of Major General George Crook detached from the Army of the Potomac. Grant's objectives remained the same although he thought it unlikely the Confederates would be drawn into open battle.[30][32]

Lee's orders

Confederate General-in-chief Robert E. Lee, who was already concerned about the ability of his weakening army to maintain the defense of Petersburg and Richmond, realized that the Confederate defeat at Fort Stedman would encourage Grant to make a move against his right flank and communication and transportation routes. On the morning of March 29, 1865, Lee already had prepared to send some reinforcements to the western end of his line and had begun to form a mobile force of about 10,600 infantry, cavalry and artillery under the command of Major General George Pickett and cavalry commander Major General Fitzhugh Lee. This force would go beyond the end of the line to protect the key junction at Five Forks from which a Union force could access the remaining open Confederate roads and railroads.[33][34]

Union troop movements

Before dawn on March 29, 1865, Warren's V Corps moved west of the Union and Confederate lines while Sheridan's cavalry took a longer, more southerly route toward Dinwiddie Court House. Humphrey's II Corps filled in the gap between the existing end of the Union line and the new position of Warren's corps. Warren's corps led by Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain's First Brigade of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Charles Griffin's First Division of the V Corps proceeded north on the Quaker Road toward its intersection with the Boydton Plank Road and the Confederates' nearby White Oak Road Line.[24][35][36]

Battle of Lewis's Farm

Along Quaker Road, across Rowanty Creek at the Lewis Farm, Chamberlain's men encountered brigades of Confederate Brigadier Generals Henry A. Wise, William Henry Wallace and Young Marshall Moody which had been sent by Fourth Corps commander Lieutenant General Richard H. Anderson and his only present division commander, Major General Bushrod Johnson, to turn back the Union advance. A back-and-forth battle ensued during which Chamberlain was wounded and almost captured. Chamberlain's brigade, reinforced by a four-gun artillery battery and regiments from the brigades of Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Edgar M. Gregory and Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Alfred L. Pearson, who was later awarded the Medal of Honor, drove the Confederates back to their White Oak Road Line. Casualties for both sides were nearly even at 381 for the Union and 371 for the Confederates.[37][38][39][40][41]

After the battle, Griffin's division moved up to occupy the junction of the Quaker Road and Boydton Plank Road near the end of the Confederate White Oak Road Line.[42] Late in the afternoon of March 29, 1865, Sheridan's cavalry occupied Dinwiddie Court House on the Boydton Plank Road without opposition.[43] The Union forces had cut the Boydton Plank Road in two places and were close to the Confederate line and in a strong position to move a large force against both the Confederate right flank and the crucial road junction at Five Forks in Dinwiddie County to which Lee was just sending Pickett's mobile force defenders.[38][44][45] The Union Army was nearly in position to attack the two remaining Confederate railroad connections with Petersburg and Richmond, if they could take Five Forks.[43][44][45]

Encouraged by the Confederate failure to press their attack at Lewis's Farm and their withdrawal to their White Oak Road Line, Grant decided to expand Sheridan's mission to a major offensive rather than just a possible battle or a railroad raid and forced extension of the Confederate line.[42][44]

Battle of White Oak Road

On the morning of March 31, General Lee inspected his White Oak Road Line and learned that the Union left flank held by Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres's division had moved forward the previous day and was "in the air." A wide gap also existed between the Union infantry and Sheridan's nearest cavalry units near Dinwiddie Court House.[46][47] Lee ordered Major General Bushrod Johnson to have his remaining brigades under Brigadier General Henry A. Wise and Colonel Martin L. Stansel in lieu of the ill Young Marshall Moody,[46][48][49] reinforced by the brigades of Brigadier Generals Samuel McGowan and Eppa Hunton, attack the exposed Union line.[46][48]

Stansel's, McGowan's and Hunton's brigades attacked both most of Ayres's division and all of Crawford's division which quickly had joined the fight as it erupted.[50][51] In this initial encounter, two Union divisions of over 5,000 men were thrown back across Gravelly Run by three Confederate brigades.[52] Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Charles Griffin's division and the V Corps artillery under Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Charles S. Wainwright finally stopped the Confederate advance short of crossing Gravelly Run.[50][51][52][53] Adjacent to the V Corps, Major General Andrew A. Humphreys conducted diversionary demonstrations and sent two of Brigadier General Nelson Miles's brigades from his II Corps forward. They initially surprised and, after a sharp fight, drove back Wise's brigade on the left of the Confederate line, taking about 100 prisoners.[50][51][54]

At 2:30 pm, Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain's men forded the cold, swollen Gravelly Run, followed by the rest of Griffin's division and then the rest of Warren's reorganized corps.[55][56][57] Under heavy fire, Chamberlain's brigade, along with Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Edgar M. Gregory's brigade, charged Hunton's brigade and drove it back to the White Oak Road Line, allowing Chamberlain's and Gregory's men across White Oak Road.[51][57][58] The remainder of the Confederate force then had to withdraw to keep itself from being outflanked and overwhelmed.[57] Warren's corps ended the battle again across a section of White Oak Road between the end of the main Confederate line and Pickett's force at Five Forks, cutting direct communications between Anderson's (Johnson's) and Pickett's forces.[51][57][59] Union casualties (killed, wounded, missing – presumably mostly captured) were 1,407 from the Fifth Corps and 461 from the Second Corps and Confederate casualties have been estimated at 800.[notes 3][60]

Battle of Dinwiddie Court House

About 5:00 p.m. on March 29, 1865, Union Major General Philip Sheridan led two of his three divisions of Union cavalry, totaling about 9,000 men counting the trailing division, unopposed into Dinwiddie Court House, Virginia, about 4 miles (6.4 km) west of the end of the Confederate lines and about 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the important road junction at Five Forks, Virginia.[24][43][61] Sheridan planned to occupy Five Forks the next day. That night, under orders from General Robert E. Lee, Confederate Major General Fitzhugh Lee led his cavalry division from Sutherland's Station to Five Forks to defend against an anticipated Union drive to the South Side Railroad, which would be intended to end use of that important final Confederate railroad supply line to Petersburg.[62][63] Fitzhugh Lee arrived at Five Forks with his division early on the morning of March 30 and headed toward Dinwiddie Court House.[64]

On March 30, 1865, in driving rain, Sheridan sent Union cavalry patrols from Brigadier General Thomas Devin's division to seize Five Forks, the key junction for reaching the South Side Railroad.[65] Devin's force unexpectedly found and skirmished with units of Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry division.[66][67][68] That night Confederate Major General George Pickett reached Five Forks with about 6,000 infantrymen in five brigades (under Brigadier Generals William R. Terry, Montgomery Corse, George H. Steuart, Matt Ransom and William Henry Wallace) and took overall command of the operation as ordered by General Lee.[69][64] The cavalry divisions of Major Generals Thomas L. Rosser and W. H. F. "Rooney" Lee arrived at Five Forks late that night.[64] Fitzhugh Lee took overall command of the cavalry and put Colonel Thomas T. Munford in charge of his own division.[64][70]

The rain continued on March 31.[71] Under Sheridan's direction, Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Wesley Merritt sent two of Devin's brigades toward Five Forks and held one brigade in reserve at J. Boisseau's farm.[72][73][74][75] Sheridan sent brigades or detachments from Major General George Crook's division to guard two fords of a swampy stream just to the west, Chamberlain's Bed, in order to protect the Union left flank from surprise attack and to guard the major roads.[72][76] Dismounted Union troopers of Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Charles H. Smith's brigade armed with Spencer repeating carbines held up Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry attack at the southern ford, Fitzgerald's Ford.[77][78] At about 2:00 pm, Pickett's force crossed the northern ford, Danse's Ford, against a small force from Brigadier General Henry E. Davies's brigade, which was left to hold the ford while much of the brigade unnecessarily moved to help Smith and could not return fast enough to help the few defenders.[79]

Union brigades and regiments fought a series of delaying actions throughout the day but were consistently eventually forced to withdraw toward Dinwiddie Court House.[80][81] The brigades of Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Alfred Gibbs and Brigadier General John Irvin Gregg, later joined by Colonel Smith's brigade, held the junction of Adams Road and Brooks Road for two to three hours.[82][83][84] Meanwhile, Sheridan had called up Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer with two brigades of his division under Colonels Alexander C. M. Pennington, Jr. and Henry Capehart.[82][84][85] Custer set up another defensive line about 0.75 miles (1.21 km) north of Dinwiddie Court House, which together with Smith's and Gibbs's brigades, held off the attack by Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee until darkness ended the battle.[84][85][86][87] Both armies initially stayed in position and close to each other after dark.[85][88][89] The Confederates intended to resume the attack in the morning.[88][48]

The Confederates did not report their casualties and losses.[88] Historian A. Wilson Greene has written that the best estimate of Confederate casualties in the Dinwiddie Court House engagement is 360 cavalry, 400 infantry, 760 total killed and wounded.[90] Union officers' reports showed that some Confederates also were taken prisoner.[82] Sheridan suffered 40 killed, 254 wounded, 60 missing, total 354.[notes 4][90] Pickett lost Brigadier General William R. Terry to a disabling injury. Terry was replaced as brigade commander by Colonel Robert M. Mayo.[91][92]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

V Corps and Mackenzie's division join Sheridan

Early in the evening of March 31, 1865, Union V Corps commander, Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, recognized from the sound of battle that Sheridan's cavalry was being pushed back at Dinwiddie Court House and sent Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett's brigade to reinforce Sheridan.[93][94][95] Moving cross country, Bartlett's men drove Confederate pickets from Dr. Boisseau's farm, just east of Crump Road.[96] Since the Gravelly Run bridge on the Boydton Plank Road had been wrecked by the Confederates, Pearson was delayed.[97] At about 8:20 pm, Warren told Meade about the needed bridge repair and possible delay but Meade did not pass the information to Sheridan.[98][99]

Meade told Warren to have his entire force ready to move.[100] By 9:17 pm, Warren was ordered to withdraw from the line and send a division to Sheridan at once.[101] At 9:45 pm, Meade first advised Grant of Bartlett's forward location at Dr. Boisseau's farm and inquired of Grant whether Warren's entire corps should go to help Sheridan. Meade did not tell Grant that the plan to move Warren's entire corps to Sheridan's aid was Warren's idea.[102]

When Grant then notified Sheridan that the V Corps and Ranald Mackenzie's division from the Union Army of the James had been ordered to his support, he gratuitously and without any basis said that Warren should reach him "by 12 tonight."[98][103][104] It was impossible for the tired V Corps soldiers to cover about 6 miles (9.7 km) on dark, muddy roads with a bridge out over Gravelly Run along the way in about an hour.[98][103][104][105] Through the night, no one gave Sheridan accurate and complete information about Warren's dispositions, logistical situation and when he received his orders.[105] Nonetheless, Warren's supposed failure to meet his schedule was something for which Sheridan would hold Warren to account.[notes 5][98][103][104]

When Mackenzie's division reached Dinwiddie Court House about dawn, Sheridan ordered them to rest since they had been on the road since 3:30 am.[106][107]

Meade's further order to send Griffin's division down the Boydton Plank Road and Ayres's and Crawford's divisions to join Bartlett at Dr. Boisseau's farm so they could attack the rear of the Confederate force did not acknowledge the large Confederate force at Dr. Boisseau's farm and the needed repair of the Gravelly Run bridge.[104] Meade learned of the Gravelly Run bridge problem when the telegraph was restored at about 11:45 pm.[108] Warren also received information from a staffer that a Confederate cavalry force under Brigadier General William P. Roberts held the junction of Crump Road and White Oak Road, threatening to hold up or stop a direct move by the V Corps to Dinwiddie Court House or Five Forks.[104]

Warren rejected Meade's suggestion to consider alternate routes because it would take too long to move his corps, even considering the existing delays.[109] Ayres had received Warren's order to move to the Boydton Plank Road at about 10:00 pm. This required him to move over about two miles of rough country and cross a branch Gravelly Run.[109] Warren allowed Crawford's and Griffin's men to rest where they were until he learned that Ayres's division had made contact with Sheridan's cavalry.[109]

Warren was told that the new Gravelly Run bridge was completed at 2:05 am.[110] Ayres's division arrived at Sheridan's position near dawn. As predicted by Warren, the effect of Bartlett's appearance threatening Pickett's flank was enough for Pickett to withdraw to Five Forks, which the Confederates had done by the time Ayres reach Dinwiddie Court House.[95][111][112] One of Sheridan's staff officers met Ayres and told him that his division should have turned on to Brooks Road, a mile back.[113][114] Ayres returned to Brooks Road, where a lone Confederate picket promptly fled as the division approached and, after Sheridan rode up for a brief meeting with Ayres, Ayres's men settled down for a rest until 2:00 pm.[113]

At 4:50 am, Warren received Sheridan's 3:00 a.m. message to cooperate with the cavalry by hitting Pickett's retreating men in the flank and rear.[115] This was similar to the plan Warren had proposed earlier in the evening but which had been given no consideration by Grant and Meade at that time.[116] Warren personally began to arrange the move of Griffin's and Crawford's divisions.[116] Warren had to carefully move Griffin's and Crawford's divisions because of the possibility of attack from the Confederates as the men withdrew from the White Oak Road Line and again at positions near Dinwiddie Court House where Confederates had been positioned while in contact with the Union cavalry earlier. Warren personally supervised Crawford's division's withdrawal and movement, leaving Warren at the end of the column when the troops moved.[117] Despite Warren's problems and Pickett's earlier retreat which would have prevented Warren from reaching him short of Five Forks, Sheridan blamed Warren for slow movements which gave Pickett the time to complete his retreat.[118]

About 5:00 am, Griffin's division was told to move to the left to J. Boisseau's house.[119] Since Warren did not definitely know that Pickett had withdrawn his force, he still thought Griffin could intercept the Confederates.[119] Griffin moved Chamberlain's brigade at the head of his column in line of battle with great care because Griffin thought they might strike the Confederate force if they emerged from White Oak Road while his division moved toward Crump Road.[120] The Confederates did not attack and Griffin advanced on Crump Road.[120] With a Confederate counterattack still thought to be possible as Crawford moved, Warren remained with Crawford until he reached Crump Road when Warren perceived that the Confederates from the White Oak Road Line were not going to wait for or follow the moving Union division.[120]

Sheridan was upset that a chance to strike Pickett was lost and was even more upset to find out from Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain at the head of Griffin's column at about 7:00 a.m. that Warren was at the end of the column.[114] Sheridan exclaimed: "That is where I should expect him to be!"[121] Warren's men knew this was an unfair comment because Warren had never shown a lack of personal bravery.[122] Chamberlain's further explanation about why Warren was in that position seemed to calm Sheridan at the time.[121] Warren thought he was doing what he should to be sure that disengagement of his corps in close contact with the enemy was made carefully.[114] Sheridan instructed Griffin to place his men 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of J. Boisseau's farm, while Ayres's remained 0.75 miles (1.21 km) south of Griffin.[122] Crawford's division arrived soon thereafter.[106][121][122] After seeing Crawford off and checking for any men or wagons not moving in the right direction, Warren and his staff then rode to join Griffin at about 9:00 am. Meanwhile, Griffin had met Devin's cavalry division at J. Boisseau's where he stopped his division and reported to Sheridan who was at the scene.[122]

At 6:00 am, Meade's Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb, had sent an order to Warren to report to Sheridan for further orders, which officially transferred Warren and his corps to Sheridan's command at that time.[121][123] Two of Warren's divisions had reported to Sheridan within an hour of the dispatch of that message.[124][125] A staff officer rode up to Warren at about 9:00 a.m. and handed him Webb's message. At the same time that Webb sent this message to Warren, 6:00 am, Meade sent a telegram to Grant stating that Warren would be at Dinwiddie soon with his whole corps and would require further orders.[123] Warren reported to Meade on the successful movement of the corps and stated that while he had not personally met with Sheridan, Griffin had spoken with him.[123] Warren did not personally meet with Sheridan until 11:00 am.[121][126][127] The failure of Warren to immediately report directly to Sheridan may have contributed to his being relieved from command later on April 1.[123] At their brief meeting, Sheridan told Warren to hold his men at J. Boisseau's farm but expressed some displeasure with Warren's remarks during the meeting.[128]

When Sheridan soon moved off to the front,[126] he accepted distorted reports that the Confederate works were stronger than they were and extended further than they did. He did not want to scout them further because he thought his plans might be given away by such activity. This left the mistaken impression that the Confederate line extended about 0.75 miles (1.21 km) further to the east than it actually did.[129]

Pickett withdraws to Five Forks

When Pickett became aware that Union infantry divisions were arriving near his flank at about 10:00 pm, he withdrew to his modest log and dirt defensive line about 1.75 miles (2.8 km) north at Five Forks.[95][111][130][131] The Confederates withdrew between 2:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., covered by Munford's cavalry and with Custer's men close behind but not forcing an engagement.[132]

After Pickett returned to Five Forks on the morning of April 1, 1865, he surmised that the Union forces were organizing to attack his left flank. He later recalled that he sent a telegram to General Robert E. Lee asking for reinforcements and a diversion to prevent his force from being isolated by Sheridan's men coming between his force and the end of the White Oak Road defenses.[notes 6][132] Pickett also said that he would have deployed north of Hatcher's Run[116][132] had he not received a telegram from General Lee that, according to many historians, stated:

Hold Five Forks at all hazards. Protect road to Ford's Depot and prevent Union forces from striking the Southside Railroad. Regret exceedingly your forces' withdrawal, and your inability to hold the advantage you had gained.[notes 7][133]

Historian Edward G. Longacre discounts the reliability of the report of this message, saying it was recalled 30 years later by Pickett's widow, who tended to exaggerate, distort and falsify her husband's records.[134] He wrote that Pickett's report only mentions Lee's direction to protect the road to Ford's Depot and that no copy of the message has ever been found, which historian Douglas Southall Freeman also had noted in 1944.[notes 8][134]

Robert E. Lee knew that if the Union Army could take Five Forks, they would be able to reach the South Side Railroad and the Richmond and Danville Railroad, cutting the major supply routes to and retreat routes from Petersburg and Richmond, cut the wagon roads to the west and circle around Hatcher's Run and attack the Confederate right flank.[135] Even if it were not the best location for a defense, Five Forks had to be defended.[135][136] Pickett later wrote that he assumed Lee had his message and would make a helpful diversion and send reinforcements.[134][135]

The slow withdrawal and narrow roads kept the last of the Confederate force from reaching Five Forks until midmorning on April 1.[134] When the Confederates reached Five Forks, they began to improve the trenches and fortifications, including establishing a return or refusal of the line running north of the left or eastern side of their trenches.[137][138] While particular attention was given to improving the refused left flank, Pickett did not have the line that initially had been constructed when his men had reached Five Forks substantially improved after his men returned from Dinwiddie Court House.[notes 9][139][140][141] The location of the line was not well chosen because some of it was in low places.[142]

Disposition of Confederate force

Not only did the Confederate line at Five Forks consist only of slim pine logs with a shallow ditch in front but Pickett's disposition of his force was poor. The cavalry in particular were poorly placed in wooded areas inundated by heavy streams so that they could only move to the front by a narrow road.[139][140] The artillery was poorly placed by Pickett, especially Colonel Willie Pegram's three guns set at the center of the line.[143] At the Warren Court of Inquiry 24 years later, Fitzhugh Lee said the Confederates made less careful dispositions than usual along White Oak Road at Five Forks because they expected to face only cavalry or to be supported by Lieutenant General Richard Anderson's corps if Union infantry left their lines to support Sheridan's force.[144] Historian Ed Bearss has written that Fitzhugh Lee and Pickett either did not know the result of the Battle of White Oak Road or failed to realize its significance.[144][145] Two of Major General Bushrod Johnson's brigades, from Anderson's only division, already were with Pickett and the troops left at White Oak Road and Claiborne Road were weakened and cut off to the west after the battle.[144] General Lee decided to send no reinforcements to Pickett because he had no notification that Pickett's force was in trouble.[146]

Pickett's line across Five Forks was dug mainly just north of White Oak Road, with a "refused" (bent back) left flank. It extended about 1.75 miles (2.82 km) about half on each side of the junction of White Oak Road with Dinwiddie Court House Road (Ford's Road to the north) and Scott Road. Pickett placed W. H. F. "Rooney" Lee's cavalry on the right of the line with Rufus Barringer's brigade watching the right flank at the western edge of Gilliam's farm. From right to left the line was held by the brigades of Brigadier General Montgomery Corse, Colonel Robert M. Mayo, who replaced the injured Brigadier General William R. Terry, and Brigadier Generals George H. Steuart, William Henry Wallace and Matt Ransom. On the left flank, the 8th Virginia Cavalry Regiment from Colonel Thomas T. Munford's division was in contact with the understrength cavalry brigade led by the Confederate Army's youngest general, Brigadier General William Paul Roberts. This small unit of a regiment plus a battalion was assigned to cover the 4 miles (6.4 km) between the end of Pickett's line and the end of the main Confederate defensive line at the junction of Claiborne Road and White Oak Road. The rest of Munford's division was positioned on Ford's Road behind the center of the line at Five Forks. Three of artillery Colonel Willie Pegram's six guns were placed along the line where fields of fire in the wooded location could be found, with the other three placed in battery at Five Forks. Four guns of Major William M. McGregor's Battalion were put on the right flank.[147][148][149][150] Thomas L. Rosser's division was in reserve, watching the wagon train north of Hatcher's Run.[148][150][151] Rosser later recalled that he asked for this assignment because his horses had been ridden hard and needed attention.[143][147]

Pursuit of Pickett's force

At dawn on April 1, 1865, Custer reported to Sheridan that his scouts had found that the Confederates had withdrawn from their positions in front of the line confronting the final Union defensive line set up on the evening of March 31 about 0.75 miles (1.21 km) north of Dinwiddie Court House. After Pickett's withdrawal, Sheridan planned to attack the Confederates at Five Forks as soon as possible.[118] Sheridan ordered Merritt to pursue Pickett's force with Custer's and Devin's divisions.[92] Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) William Wells's brigade of Custer's division was recalled from guarding the wagon train.[152]

When Custer reached the junction of Adams Road and Brooks Road with Pennington's and Capehart's brigades, he found Ayres's division of Warren's corps had arrived at that location about dawn.[notes 10][106] Due to the wet ground, Merritt decided to deploy Custer's men dismounted and move them cross country to turn the Confederate right flank.[92][152] Custer moved his men forward with Pennington's brigade on the left and Capehart's on the right, with Chamberlain's Bed and Bear Swamp to the cavalrymen's left.[153] Custer's troopers captured a few Confederate stragglers and drove off a patrol guarding the Scott Road crossing of Bear Swamp.[154] When Custer's men approached within several hundred yards of the Confederate defensive line at White Oak Road, he decided not to attack the apparently strong defenses but to send out combat patrols to test the line. They could not find a weak spot in the line so Custer told his men to hold their ground.[154]

When Custer's troops moved off the Dinwiddie Court House Road, Merritt sent Devin's force up that road to J. Boisseau's farm where they met Griffin's division, which had begun to arrive about 7:00 am, with Crawford's division following soon thereafter.[106][121][154] After Devin had met with Griffin, he moved toward Five Forks. Stagg's brigade discovered that Confederate infantry held the crossing of Chamberlain's Bed in force.[154] Devin then sent Fitzhugh's dismounted brigade to ford the creek and establish a position on the other side.[155] Stagg then sent his mounted force along with the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment to follow Fitzhugh's men across while the rest of Gibbs's brigade covered the right flank and rear of the division.[155] Devin then sent the dismounted brigade flanked by the mounted troopers to take a wooded area between Chamberlain's Bed and White Oak Road. The mounted men got within 20 yards (18 m) of the Confederate line and some of the dismounted men even briefly crossed the line and brought back some prisoners before being driven off.[139][155] Stagg dismounted his brigade and moved them into the line. Gibbs's brigade also was brought forward to oppose the center of the Confederate line and was dismounted except for one regiment, the 1st U.S. Cavalry.[155]

Custer's division was on the left of the Union line and its farthest right brigade, Pennington's, was at first in contact with Stagg's 1st Michigan Cavalry from Devin's division but the 1st Michigan moved off to look for the rest of their brigade which was in the middle of Devin's line.[155] Pennington then moved back to reform his line and to move to the right in thick woods about 600 yards (550 m) south of the Confederate line.[156] After this move, Pennington was across Scott Road from Fitzhugh's brigade, rather than from Stagg's brigade. The dismounted troopers threw up log breastworks while waiting for further orders.[107]

Wells's brigade of Custer's division arrived at Dinwiddie Court House with the wagons at 11:00 am. After Wells allowed his men to rest until 1:00 pm, they moved up to the battle line to report to Custer.[107] Davies's and Smith's brigades of Crook's division were assigned to guard the wagon trains when Wells's brigade moved forward. One of Davies's regiments was sent to watch the Boydton Plank Road bridge across Stony Creek. Gregg's brigade of Crook's division was sent across Chamberlain's Bed at Fitzgerald's Ford to seize Little Five Forks. That junction controlled the roads to the left and rear of Custer's division.[107] Gregg sent out patrols to be sure the Confederates could not make a surprise attack on Sheridan's left flank.[107]

Grant sends Sheridan permission to relieve Warren

Just before noon, one of Grant's staff, Lieutenant Colonel Orville E. Babcock, told Sheridan:

General Grant directs me to say to you, that if in your judgment the Fifth Corps would do better under one of the division commanders, you are authorized to relieve General Warren, and order him to report to General Grant, at headquarters.[157][158][159]

Sheridan replied to Babcock that he hoped that would not be necessary.[157][158] Grant had issued the order in part because a staff officer mistakenly reported to him at about 10:00 a.m. that Warren's corps still was held up at Gravelly Run.[127] Warren did not hear about Grant's message but some word leaked out to V Corps generals including Griffin and Chamberlain.[160]

Sheridan's plan of attack; V Corps called up

Sheridan then planned an attack whereby Custer would feint toward the Confederate right flank with Capehart's brigade, Warren's infantry corps would attack the left flank and Devin, joined by Pennington's brigade, would make a frontal attack on the Confederate entrenchments when they heard Warren's attack begin.[106][139][148][157][158] Sheridan sent a staff officer to order up the V Corps and an engineer, Captain George L. Gillespie, to turn the front of Warren's Corps into Gravelly Run Church road obliquely to and a short distance from White Oak Road, about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Five Forks.[157] In the Warren Court of Inquiry in 1880, Gillespie testified that contrary to Sheridan's after action report, he had made no reconnaissance of the Confederate line and did not know there was a "return" on the left flank. He only knew he was to align the V Corps with the right flank of Devin's division and have them positioned as a turning column a short distance from White Oak Road and about 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Five Forks.[161][162]

Gillespie reached Warren at J. Boisseau's farm at 1:00 p.m. with Sheridan's instructions.[148] Upon hearing Sheridan's order, Warren sent Colonel Henry C. Bankhead to have the division commanders move up at once.[163] Bankhead gave Crawford and Griffin the message and sent another officer to contact Ayres while he waited to see that the orders were obeyed as promptly as possible by the divisions at the farm.[163]

Warren went to see Sheridan who briefly and tersely explained to him the tactical situation and plan of operations.[106][129][163] Warren then rode to examine the ground where his men were to be massed on Gravelly Run Church Road and he sent his escort to patrol as far as White Oak Road to prevent the Confederates from discovering the V Corps' movement.[163][164]

Sheridan told Warren to advance with his entire corps in a two-division front oblique to the road with the third division following in reserve. He wanted the attack in a single blow and not piecemeal.[163] Otherwise, Warren could determine the number of assault waves and length of the line. Warren decided that each division should put two brigades in front in double battle lines with their third brigade centered behind the first two.[165] Warren's corps would cover about a 100 yards (91 m) front with about 12,000 officers and men, reduced from 15,000 by casualties, detachments and stragglers over the past 3 days.[166]

Crawford's division reached Gravelly Run Church first and deployed as Warren instructed.[165] Griffin's division arrived soon after Crawford's. Warren showed him where to set up and asked him to be as expeditious as possible in forming his line.[165] Ayres's division arrived last and Warren also asked him at least twice to move expeditiously.[166][167]

If the angle or "return" in the Confederate line had been where Warren was led to believe it was, Crawford's men would hit it first and Griffin would be with him to reinforce the attack.[106][166][168][169] Ayres division would prevent the Confederate troops in the earthworks facing White Oak Road from reinforcing Ransom's brigade which was holding the return.[166][167] Warren prepared a sketch map of the presumed situation for the division commanders.[166][170][171] Warren had to draw up the orders in reliance on what he was told about the location of the Confederate line and without making a personal reconnaissance.[172] Colonel James W. Forsyth, Sheridan's chief of staff said that Sheridan also saw a copy of Warren's diagram and instructions and approved them.[172][173] The instructions directed the corps to advance northwestwardly to the White Oak Road, wheel to the left, take a position at right angles to the road and that as soon as they were engaged, Custer's and Devin's men were to charge along the rest of the line.[174] No cavalry were on the right with the V Corps but Mackenzie's troopers were reported to be advancing on White Oak Road toward the V Corps' position.[174]

The ground where the V Corps formed was rough, wooded and filled with ravines. Since the Confederate breastworks could not be seen from this location, the direction of advance depended on the roads and supposed location of the Confederate works along White Oak Road.[174]

Warren "used all exertions possible" to get his troops to the point of departure.[174] The march appeared to be off to a good start. Griffin received his orders at 2:00 pm. The division marched 2.5 miles (4.0 km) over a narrow, woody road, arriving at the marshaling area about 4:00 pm, which most observers agreed was reasonable time, especially since the road was muddy and blocked by led horses of dismounted cavalry.[160][174] Sheridan came to visit Warren during the V Corps organizational movements and expressed concern that Warren get ready before his cavalry fired all their ammunition.[106][174][175] Warren offered to move with those troops which were ready if Sheridan so directed, but Sheridan wanted all the infantry to attack at once.[174][175]

Sheridan felt that Warren was not exerting himself to get the corps into position and stated in his after action report that he was anxious for the attack to begin as the sun was getting low and there was no place to entrench.[160][176] Warren denied Sheridan's allegation that Warren had given the impression he wanted the sun to go down before the attack could be made and that there were 2.5 hours of daylight still left at 4:00 pm.[notes 11][171][176]

Mackenzie disperses Roberts's cavalry

While the V Corps was organizing for its attack, Sheridan was further disturbed to learn that Meade had pulled Miles's division from the White Oak Road line back to the Boydton Plank Road, opening the possibility that Confederate reinforcements could come down White Oak Road and strike the V Corps in the flank and rear.[177] Sheridan called up Mackenzie's division.[178] They moved up the Adams and Dinwiddie Court House Roads to J. Boisseau's and turned on to the Crump Road, intending to move to the White Oak Road and set up a roadblock, with Major James E. McFarlan's battalion of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry in the lead.[177]

About 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of White Oak Road and 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Five Forks, Mackenzie's troopers encountered a considerable force of Roberts's men posted in rifle pits along the edge of a wood along White Oak Road with an open field to their front.[161][177] Rapid fire from Mackenzie's men who were armed with Spencer repeating carbines kept the Confederates pinned down and allowed Mackenzie personally to lead Major Robert S. Monroe's battalion of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry on horseback across the rifle pits into White Oak Road, striking the left flank of the Confederate line.[177] The North Carolina cavalrymen retreated in confusion as the remainder of the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry charged the Confederate cavalry's line.[177][178][179] Union brigade commander Colonel Samuel P. Spear was wounded in the mopping up operation.[180]

When he was informed of Mackenzie's success, Sheridan ordered Mackenzie to leave a detachment to block White Oak Road and to bring his division to Five Forks.[161][180] When Mackenzie reached a position near the Confederate line and was about to order his lead brigade to charge, the V Corps started across White Oak Road, briefly delaying both units' progress to their positions.[180]

Pickett, Fitzhugh Lee away at shad bake

From north of Hatcher's Run, Fitzhugh Lee's other division commander, Thomas L. Rosser, invited Lee and Pickett to a shad bake lunch. Rosser had brought a large catch of shad on ice from the Nottoway River when his division moved from that station to Five Forks.[181][182] Pickett and Lee accepted.[181][182] At 2:00 pm, as Lee was about to leave the line, Munford came up to report a dispatch from a lieutenant of the 8th Virginia Cavalry who wrote that Roberts's cavalry brigade stationed to the east along the White Oak Road had been overpowered by Union cavalry.[183][184] Some of Roberts's men fled into Pickett's line while others retreated into Anderson's end of the main Confederate White Oak Road line at Claiborne and White Oak roads.[185] The dispersal of Roberts's command meant that Pickett was cut off and if any reinforcements were sent, they would need to fight their way through on White Oak Road to reach his position or take a very circuitous route.[186] Fitzhugh Lee asked Munford to check this personally and to order up his division if necessary and report back.[182][183][186] Munford then saw Lee riding with Pickett north on Ford's Road toward Hatcher's Run but had no knowledge of their destination, which was about 1.25 miles (2.01 km) north of the front.[183][186]

After Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee had departed, Major General Rooney Lee was the senior officer in charge, though he was at the far right of the line and did not know he was in charge.[169][181][186] With Rooney Lee in overall command, Colonel Munford, who was better located in any event, would be the senior cavalry officer, while Brigadier General Steuart was the ranking infantry commander.[186] None of these officers knew that Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee were at the rear having a lengthy lunch and that they should assume additional duties.[133][169][182][183][186][notes 12]

Soon after Pickett and Fitzhugh Lee left for lunch, Colonel Munford saw the Union attack shaping up as he prepared to have his cavalry division defend the left flank against the attack.[187] Munford sent several couriers to look for Pickett or Fitzhugh Lee to tell them of the impending attack but they could not be found.[188][189] Captain Henry Lee of Fitzhugh Lee's staff also could not find them.[188][189] Munford had his division dismount, and deployed it on the left of Ransom's refused line.[189] Each Confederate unit commander prepared for the attack as best he could, not always in co-operation with each other.[189]

Ayres starts V Corps attack; Sheridan at front

When Ayres finished aligning his men, about 4:15 pm, the order was given for the attack.[169][189] Sheridan, Warren and Colonel Porter rode at the front of Ayres's division.[189] Union skirmishers drove in the Confederate outposts.[189] Ayres was told by a staff officer that there were indications of the enemy to the left.[189] Ayres alerted his reserve brigade commander Brigadier General Frederick Winthrop to be ready to bring his brigade forward.[189]

As Ayres's men crossed White Oak Road, they ran into Mackenzie's approaching cavalry.[190] Sheridan had ordered Mackenzie to strike toward Hatcher's Run, turn west and occupy Ford's Road, covering the V Corps' right flank.[190][191] Warren soon realized that the V Corps had crossed White Oak Road east of the left of the Confederate line and Crawford's division was starting to diverge from Ayres's.[190] Warren thought that the Confederate line must be in the edge of the woods, about 300 yards (270 m) from the road and continued to lead the corps toward the northwest.[161][190]

Ransom's Confederate brigade began to fire on Ayres's division after they crossed White Oak Road and entered a field beyond.[169] This established that the Confederate line was not immediately across White Oak Road from Gravelly Church Road but 700 yards (640 m) to 800 yards (730 m) west of that intersection.[106][161][190] The bad information about the location of the Confederate line had put the V Corps' march off target, with two of the three divisions past the end of the Confederate line but in a position to strike from the rear.[179]

Warren later recalled that Ransom's brigade was in a thick belt of woods, which disrupted their aim and reduced initial Union casualties.[190] The Confederate refused left flank was shorter than 150 yards (140 m) in length.[190] Ayres realized the situation soon after the attack began and changed his front to the left to face the return (bend) of the line.[169][190][192] The movement of Colonel Richard N. Bowerman's brigade to the left opened a space in the line which Ayres filled with Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Frederick Winthrop's brigade which had started in reserve.[190][192][193] Ayres then led the line in the attack.[190] Crawford, however, failed to adjust his movement when Ayres changed his front and Griffin continue to follow Crawford north and west through the woods.[194]

Ayres's men had faltered briefly when they became exposed to closer, more accurate firing from Ransom's brigade.[171][192][195] Sheridan then rode along the battle line shouting encouragement.[notes 13][192] When a soldier was hit in the neck and fell shouting "I'm killed!" Sheridan called to him "You're not hurt a bit, pick up your gun, man, and move right on to the front."[171][195] Reacting to Sheridan's words, the man stood up, picked up his gun and moved a dozen paces before he finally collapsed dead.[171][195]

Ayres's right flank brigade under Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) James Gwyn had moved well ahead of Crawford's division and began to waver as the troops realized they might be exposed to a flank attack.[196] On his horse, Sheridan called for his battle flag.[171][196] He rode among the soldiers shouting encouragement, threats, profanities and orders to close ranks.[196][197] His color sergeant was killed.[196] Another staff officer was wounded and at least two other staff officers' horses were killed.[196][197] Sheridan and Ayres and his officers managed to quickly get the troops under control and order them forward again.[196] This time some of Ransom's defenders broke for the rear.[196] McGregor's gunners limbered up their four artillery pieces and pulled out just as Ayres's men came over the earthworks.[196] Ayres's men killed or captured all of Ransom's men who had not fled.[notes 14][196]

As some of his men got away from the crumbling line, Ransom had to be freed from under his wounded and grounded horse.[198][199] An officer in one of Ransom's regiments later wrote: "The Yankees simply run over us and crowded us so that it became impossible to shoot."[200] The color-sergeant of the 190th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment planted the first Union flag on the Confederate line.[196]

Sheridan jumped his horse over the berm and landed among Confederates who had thrown down their weapons and were waiting to surrender. When they asked him what to do, Sheridan pointed to the rear and said: "Go over there. Get right along, now. Drop your guns; youll never need them any more. You'll be safe over there. Are there any more of you? We want every one of your fellows."[197][201] Ayres had taken the key to the entire Confederate line, over 1,000 prisoners and eight battle flags but among the Union casualties was Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Frederick Winthrop who was mortally wounded and Colonel Richard N. Bowerman who was severely wounded.[169][201] Colonel James Grindley assumed command of Winthrop's brigade while Colonel David L. Stanton took charge of Bowerman's brigade.[201]

Soon after Sheridan jumped his horse into the Confederate works, an orderly reported to him that Colonel Forsyth of his staff had been killed.[201] Sheridan replied; "It's no such thing. I don't believe a word of it. You'll find Forsyth's alright."[201] Ten minutes later, Forsyth rode up and Sheridan shouted: "There! I told you so."[201] Sheridan ordered Ayres to halt and reform his division. When it was obvious that the Confederate line in fact had given way, Sheridan ordered Ayres to move forward.[202]

Warren searches for Griffin, Crawford

When Griffin's and Crawford's divisions diverged from Ayres, Ayres sent a message to Griffin to come up on his right.[203] Sheridan also sent orders to Griffin and Crawford to come in on the right. Warren sent staff officers in pursuit of them.[203] Warren established a command post in the field east of the return where he thought he could get information from all points and exercise control of the whole field assigned to his corps.[203] Sheridan, however, thought Warren should have been leading from the front.[203] When the staff officers did not report back promptly, Warren himself went looking for the wayward divisions.[203] He was fired upon when he reached a local landmark, the "Chimneys",[notes 15] about 800 yards (730 m) north of the end of the Confederate refused line, by the volleys that caused Gwyn's brigade to recoil.[203]

Crawford's division had come in several hundred yards from the road before they wheeled to the left, entirely missing the approximately 150 yards (140 m) Confederate return line.[204] Warren first found Colonel John A. Kellogg's brigade and told him to form his brigade at right angles to its previous direction and wait until another brigade could close up on his right.[193][204][205] Warren and his staff officers could not find Crawford to tell him to move his other brigades.[205][206] When Warren came back from the woods, Kellogg was gone, having been ordered forward by one of Sheridan's staff officers who was also searching for Crawford.[193][204][205][207] A patrol of Munford's cavalry stopped Kellogg's advance from positions inside the Sydnor house.[204] Colonel Jonathan Tarbell brought up a battalion of the 91st New York Infantry Regiment which drove out Munford's men and allowed Kellogg's brigade to resume their move to the west.[204]

One of Warren's staff officers, Major Emmor B. Cope[notes 16] found Crawford and had him swing to the right to join Kellogg.[208] Since Kellogg had moved, Crawford proceeded toward the Chimneys, with the brigades of Brigadier General Henry Baxter and Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Richard Coulter, encountering a few of Munford's pickets as they progressed.[208] Crawford then found and moved against Munford's dismounted troopers, which still moved Crawford toward the northwest away from the main Confederate line.[208]

Griffin joins the main attack

Warren finally found Griffin about 800 yards (730 m) north of the return at the Chimneys.[208][209][210] Griffin had pushed ahead of Crawford's division and had gone even further to the right of the end of the refused segment of the Confederate line.[208] Griffin realized something was wrong when he did not come up against fortifications after marching about 1 mile (1.6 km) and only finding Munford's outposts as opposition.[206][208]

Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett of Griffin's division rode to the left when he heard increased firing and saw the Confederate left flank on the opposite side of Sydnor's field.[211] Griffin also rode to Sydnor's field and saw the Confederate movement along White Oak Road.[210][211] Major Cope then rode up and told Griffin that Warren wanted him to move toward White Oak Road by the left flank.[211] Meanwhile, all of Griffin's men except three regiments of Bartlett's brigade had moved off and joined Crawford's division.[211]

Griffin then led Bartlett's three regiments across Sydnor's field.[207][211] Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain saw the division flag moving to the left and followed Griffin with his brigade and a regiment of Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Edgar M. Gregory's brigade.[194][211] By the time Warren returned to White Oak Road, Ayres's division had captured the return.[211] Since no attack was now needed at the return (refused end) of the Confederate line, Warren sent Major Cope to tell Griffin to push westward toward the Ford's Road.[211] Griffin turned his men to the right and headed west parallel to White Oak Road.[210][211] Warren then turned back toward the return to look again for Crawford's division.[210]

Second Confederate left flank line breached

The collapse of Ransom's brigade put both Wallace's and Steuart's brigades in danger of being outflanked and attacked from the rear.[212] The three Confederate brigadier generals quickly threw up a new defensive line with light field works at a right angle to White Oak Road in the woods at the west end of Sydnor's field in order to protect Ford's Road.[notes 17][169][212] Griffin's brigade soon charged against this line with Chamberlain's brigade and one of Gregory's regiments on the left, Bartlett's brigade on the right and two of Gregory's regiments behind.[169][212] When Chamberlain's men attacked, their right wing overcame the new Confederate line and then a Union regiment and a battalion headed toward White Oak Road while Griffin's remaining troops maintained their pressure on that part of the Confederate line which was still holding out.[212][213][214] Another of Chamberlain's regiments and a battalion continued to pressure the Confederate line.[212] Bartlett's regiments met stiff resistance and even engaged in hand-to-hand fighting.[212] Some of Bartlett's men took cover in rifle pits where Chamberlain's men had broken the line.[212][213] Griffin's men succeeded in breaking the line after a fight of about half an hour.[209]

The generals and staff officers had to reform Bartlett's brigade and deploy the men at right angles to the Confederate line so they would not be trapped if the Confederates managed a counterattack.[215] Chamberlain rushed two regiments to help.[215] Together, these units put the Confederates to flight, taking about 1,500 prisoners and several battle flags.[169][215] Bartlett and Chamberlain reorganized 150 to 200 stragglers and put them back into the battle.[215] Chamberlain saw Colonel Gwyn's battle flag to the rear and asked Gwyn to have his brigade assist Chamberlain's men, which Gwyn did.[213][215] Suddenly confronted by a large number of Confederates, Chamberlain feared being caught in a cross-fire when the Confederates suddenly threw down their arms and surrendered.[216]

Sheridan orders Ayres, Griffin, Chamberlain forward

As the second Confederate return line collapsed, Ayres and Sheridan came forward.[217] Sheridan ordered Chamberlain to take command of all the infantry in the vicinity and to push for Five Forks.[217] He did so with the help of one of Griffin's staff officers.[217] After being cautioned by Sheridan and Ayres that his men were firing into their own cavalry, Chamberlain told Sheridan that he should go to a safer place.[205] Instead, Sheridan rode west on White Oak Road, following Griffin and Bartlett who had just come up.[205]

Griffin had not paused with the victory at the second defensive line but continued to advance to Five Forks where he met the dismounted troopers of Pennington's and Fitzhugh's brigades who had just broken through the Confederate fortifications.[215] Ayres's division then reached Five Forks as well.[215] On the right, Bartlett's brigade reached Ford's Road and captured an ambulance and wagon train.[215]

Crawford moves forward; Warren searches again

Crawford's troops also moved steadily across Ford's Road from the northern end of Sydnor's field and captured seven ambulances and some wagons from Wallace's brigade.[209][215][218] Crawford sent these wagons with many prisoners to the rear so fast that Crawford's provost marshal could not keep an accurate count of them.[219]

After Ayres's division had captured the return, Warren again went to search for Crawford.[220][221] He found Crawford's division in good order on the east side of the Boisseau farm, facing west.[181][218][221][222] Unfortunately for Warren, Sheridan asked for Warren at about this time and no one could say where he was.[223] Sheridan then ordered Griffin to take command of the corps.[223] Meanwhile, Warren ordered Crawford to wheel to the left and drive south against Five Forks because Warren perceived that the Confederates still held the crossroads because of artillery fire coming from that direction.[221][222] Coulter's brigade led the attack on the left of Ford's Road with Kellogg's and Baxter's brigades and four of Bartlett's separated regiments coming up on the right.[220][221] From woods on the south of the Boisseau farm, the Confederates fired steadily on the Union battle line.[221][223] Three companies of the 1st Maine Veteran Infantry Regiment routed a patrol of Rosser's cavalry across Hatcher's Run before rejoining their regiment.[221] Warren assigned the 1st Maine Veteran Infantry Regiment and the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment to watch the ford across Hatcher's Run.[223][224]

Pickett learns of attack; rides back to battle

During the shad bake lunch at Rosser's camp, two of Munford's pickets rode up to report that Union forces were advancing on all roads.[188] Fitzhugh Lee and Pickett decided that since they could not hear an attack, due as it turned out to the thick pine forest and heavy atmosphere between the camp and Five Forks and an acoustic shadow, there was little to worry about.[210] Soon after 4:00 pm, Pickett asked Rosser for a courier to take a message to Five Forks.[188] Not long after that, two couriers were dispatched, the officers heard gunfire and saw the lead courier captured by Union horsemen on Ford's Road just across Hatcher's Run.[188][225][226] Then they saw a Union Army battle line coming toward the road.[225][227]

Pickett crossed the ford just as some of Munford's cavalrymen were falling back with Kellogg's brigade pressing them closely.[224][225] Pickett appealed to his cavalrymen to hold back the Union attackers long enough so he could get to the front.[224][225][228] A small group of the Confederate cavalrymen, led by Captain James Breckinridge, who was killed, charged the advancing Union soldiers, giving Pickett enough time to pass using the horse's head and neck as a shield.[224][225][228] Getting to the ford a little later than Pickett, Fitzhugh Lee was unable to cross as Kellogg's men had occupied Ford's Road by that time.[224][225][228] Lee then tried to attack the roadblock with Rosser's reserve division but they failed to breach the Union line,[224] so Lee deployed the division north of Hatcher's Run in an effort to keep the Union force from using Ford's Road to reach the South Side Railroad.[224][225]

Pickett found that his subordinates, Ransom, Steuart and Wallace, had formed a new line parallel to and east of Ford's Road and were fighting with Griffin's division.[224][229]

Third Confederate left flank formed, collapses

Pickett pulled Mayo's brigade from the line west of Five Forks along with Graham's two guns to shore up the line and added stragglers from Ransom's and Wallace's brigades to the line in order to man a third line of resistance east of Ford's Road.[181][222][225][230] Coulter's Union brigade faced fierce fire from Mayo's brigade and Graham's battery but continued to advance with the support of Crawford's two other brigades and two of Bartlett's regiments.[231]

Mayo's brigade broke when Coulter's men rushed into the woods and over their line, although Mayo was able to reform part of the brigade in Gilliam's field.[222][231] Seeing the disordered condition of Mayo's brigade, and although the Confederates still controlled the Five Forks intersection, Pickett gave up the fight at Ford's Church Road and ordered Mayo to go across country to the South Side Railroad.[222][231][232] Coulter's brigade took a large number of prisoners from Mayo's brigade and captured Graham's two guns.[231]

After Mayo's brigade had been broken, Warren told Crawford to oblique his division to the right and occupy White Oak Road west of Five Forks to close the last line for Confederate retreat.[231] Custer's and Rooney Lee's divisions were engaged in fierce combat to the southwest of Crawford.[231] Crawford's left flank passed north of Five Forks and Warren split off for Five Forks.[231] Warren met the 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment riding up Ford's Road and instructed them to file to the left and march to support Crawford.[233]

Corse, Rooney Lee cover Confederate withdrawal

When Pickett sent Mayo off the field, he called for Corse's brigade to come from the front and deploy on the west side of Gilliam's field at a right angle to White Oak Road.[232][233][234] The Union forces would need to cross this open field to advance.[233] Pickett's objective was to gain time for the survivors of the shattered brigades of Ransom, Steuart and Wallace to escape.[233] Corse's men threw up light field works and Barringer's and Beale's brigades of Rooney Lee's cavalry division supported them to the south and west.[232][233]

Mackenzie's cavalry had advanced on the right of the V Corps and scattered Munford's picket line as well as screening the infantry from any attempt by Rosser's division north of Hatcher's Run to come in from behind.[233][235] Mackenzie had to pause twice to break up pockets of resistance.[233] The Union cavalrymen captured large numbers of prisoners during their advance.[233] At about 9:00 pm, Mackenzie halted and reported his location to Sheridan.[233] Sheridan sent instructions to have a cavalry detail relieve the infantry detachment then guarding the Hatcher's Run ford on Ford's Road.[233]

After Munford and his remaining troopers crossed Hatcher's Run, they remounted, crossed back and rode to the right to report to Pickett.[236] Realizing that they only could get trapped by continuing to fight, Pickett ordered Munford to rejoin Fitzhugh Lee north of Hatcher's Run. They did so after recrossing the run to the west at W. Dabney's Road and reported to Fitzhugh Lee after dark.[236]

Union cavalry attack

In line with Sheridan's order, Merritt ordered Devin and Custer to dismount their men and charge the Confederate works as soon as they heard the sound of battle from the infantry attack.[236] They were to leave one brigade each on horseback to exploit any breakthrough.[236] Devin's men and Pennington's brigade of Custer's division attacked the fortifications along White Oak Road when they heard the infantry's attack.[236][237] Pennington was at Custer's command post where Custer told him to call for his "led horses" so he could support Custer's flank attack, contrary to Merritt's orders that he should attack dismounted along with Devin's men.[238]

Within minutes of speaking with Custer, Pennington heard the sound of firing, followed by the appearance of a staff officer who told him that Merritt had sent Pennington's brigade into the attack.[238] Custer said he must be mistaken and rode off.[238] Pennington headed for the front only to find that his brigade in fact had attacked, faltered and was pulling back in confusion.[238] In his after action report, Pennington said the failure to maintain contact with Fitzhugh's brigade, the removal of Capehart's division from his left, and the fact that his men were running out of ammunition caused the retreat.[238] With Pennington's brigade no longer on his left, Devin had to pull his division back.[238] While the Union forces regrouped, Devin supplied Pennington's men with more ammunition and the Union attack was resumed.[238] After renewing their attack, Pennington's brigade fell back again but Devin's division continued their attack against Steuart's and Wallace's brigades.[239]

After Ayres's division broke the Confederate line, Steuart and Wallace had to withdraw a large number of their troops to man the new defensive line at right angles to White Oak Road.[240] Nonetheless, Pennington's men were being held back at the breastworks and Sheridan halted them temporarily because he was concerned that Ayres's men would fire into them.[207] It was only after Mayo's brigade was pulled out of the front line to form the third left flank line that Pennington's brigade made progress.[240]

Five Forks taken; Pegram killed

The guns at Five Forks and part of Steuart's brigade still held the intersection.[222] Colonel Pegram had posted his three guns to the west of Ford's Road in a little salient as directed by Pickett, then went to sleep.[240][241] When the firing started, Pegram woke up and rushed to the Five Forks intersection.[240] Pegram's three cannon fired at the charging Union cavalrymen, who were firing at the artillerists with repeating carbines.[198] Pegram rode out between the guns to give orders without dismounting and, after shouting "Fire your canister low, men!," was mortally wounded.[198][199][210][242] Pegram died the following morning.[243]

The Confederate detachments from Mayo's, Steuart's and Wallace's brigades could not carry on holding the front of the Confederate line when Union troops from Griffin's division appeared on their left to add weight to the attack by the Union cavalrymen who charged over the fortifications as Griffin's men came up.[198][229] Devin then sent the mounted 1st U.S. Cavalry regiment after the fleeing Confederates.[169][198] The Union cavalry division commanders reported that they captured almost 1,000 prisoners and seized two battle flags and two guns during the battle.[198]

After the Union cavalry broke the front line at the Five Forks intersection, Griffin's and Ayres's infantry divisions arrived at the scene, causing some disorder as units intermingled.[169][198] After restoring organization to their commands, Devin wheeled his division to the left and set up on Griffin's left while Ayres's division was behind Griffin's.[198][234] Then the Union battle line moved to the west of the junction.[234][244]

Miles blocks White Oak Road

At 5:30 p.m. on April 1, Grant sent Brigadier General Nelson Miles's division of the II Corps to hold White Oak Road at Claiborne Road and prevent reinforcements moving to Pickett over White Oak Road.[245]

Custer held off; pursues Fitzhugh Lee

Before the Union attack began, Custer positioned Capehart's and Wells' brigades opposite the Confederate right and remounted them as ordered by Merritt.[244] Custer then told the 15th New York Cavalry Regiment to make a feint against the end of the main line held by Corse's brigade.[244] Custer planned to lead the rest of the men of the two brigades in an attack on the Confederate flank.[244] Corse had been reinforced by a dismounted brigade from Rooney Lee's cavalry division.[244] The 15th New York was turned back twice as they tried to reach Confederate cannons that were firing canister.[244][246]

Custer began his flank attack when the 15th New York Cavalry began their attack on the front and swung his mounted brigades around the Confederate flank.[244] Before Custer could seize a position behind Corse, Rooney Lee led the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry (19th State Troops) and 3rd North Carolina Cavalry (41st State Troops) in a counterattack. Lee's troopers held their position, keeping Custer from joining the Union forces moving west along the Confederate line.[244][247] Covered by Rooney Lee's troopers from Barringer's brigade, McGregor's battery, many infantry, wagons and ambulances and Beale's cavalry brigade withdrew north of Hatcher's Run.[232][248][249]

Warren leads a final charge

Warren found Crawford's division hesitating at the edge of the woods on the east side of Gilliam's field at the same time Custer's division was being held back by Rooney Lee's men to the south and west.[247][248] The Union soldiers were not heeding officers' orders to move forward against Corse's line of breastworks.[248] After a few minutes for reorganization of the units, Warren took the corps flag and rode into the field with his staff officers and called for the men to follow.[232][247][248][250] The men then rose and followed their officers and color bearers to attack Corse's brigade, capturing many prisoners and dispersing the other Confederates.[248] In the attack, Warren's horse was shot from under him just short of the Confederate line, an orderly was killed and Lieutenant Colonel Hollon Richardson of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment was badly wounded when he jumped his horse between Warren and the Confederate defenders.[232][248][251]

After Corse's brigade had been scattered, Crawford's men moved west on White Oak Road about 0.5 miles (0.80 km).[252] After mopping up a few pockets of resistance, Warren halted the pursuit since no more Confederates could be seen and night was falling.[253][254] Warren had earlier sent his aide, Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Locke, to tell Sheridan he had gained the enemy's rear, taken over 1,500 prisoners and was pushing in a division as fast as he could.[254] Sheridan told Locke: "Tell General Warren, by God! I say he was not at the front. That is all I have got to say to him."[254][255]

When Pickett ordered Corse to the west side of Gilliam's field, he ordered Rooney Lee to prepare to withdraw to the South Side Railroad.[253] Lee covered his dismounted men with his mounted men and fought a successful delaying action as he slowly retreated.[253] He had to speed up as Corse's brigade collapsed.[234][253] Yet, Custer could not cut off many of Lee's men, who crossed Hatcher's Run at W. Dabney Road and then marched to Ford's Road to report to Fitzhugh Lee.[253] Custer followed Lee's men for about 6 miles (9.7 km) but gave up and set up camp on the battlefield, where Pennington's brigade rejoined them, as darkness closed in.[253]

Casualties

Historians offer a range of casualties. Some are similar to Earl J. Hess's numbers of about 600 killed and wounded, 4,500 prisoners and thirteen flags and six guns lost by the Confederates and 633 casualties for Warren's infantry and "probably...fewer" for Sheridan's cavalry.[234] Noah Andre Trudeau gives the same number of Union infantry casualties and a total of 830 Union casualties with 103 killed, 670 wounded, 57 missing. Trudeau gives a "more modern accounting." Although earlier than Hess's account, Greene and several other historians state that the Confederates lost about 605 killed and wounded and 2,400 taken prisoner.[256] A. Wilson Greene later gives the same figures.[181] Chris Calkins also cites the lower estimate of Confederate prisoners.[257] John S. Salmon gives Union casualties as 830 and Confederate casualties as 605 plus 2,000 to 2,400 taken prisoner for a total of about 3,000 lost.[258] This is nearly identical to the National Park Service figures.[notes 18][3]

Aftermath

Confederate survivors move toward railroad

The survivors of the Confederate infantry brigades moved north through the woods and fields to ford Hatcher's Run and moved over the W. Dabney road to a position near the South Side Railroad.[253] After some order was restored to the intermingled mass of survivors, Pickett moved the men in their re-formed units toward Exeter Mills at the mouth of Whippornock Creek where he planned to ford the Appomattox River and return to the Army of Northern Virginia.[253]

Sheridan relieves Warren of command