Contents

-

(Top)

-

1Background

-

2War

-

2.1Incident in Acton and aftermath

-

2.2Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency

-

2.3Captives

-

2.4Early Dakota offensives

-

2.5State military response

-

2.6Defense along southern and southwestern frontier

-

2.7Encounters in early September

-

2.8Attacks in northern Minnesota and Dakota Territory

-

2.9Army reinforcements

-

2.10Battle of Wood Lake

-

2.11Surrender at Camp Release

-

2.12Escape and death of Little Crow

-

-

3Aftermath

-

4Monuments and memorials

-

5In popular media

-

6See also

-

7References

-

8Further reading

-

9External links

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several eastern bands of Dakota collectively known as the Santee Sioux. It began on August 18, 1862, when the Dakota, who were facing starvation and displacement, attacked white settlements at the Lower Sioux Agency along the Minnesota River valley in southwest Minnesota.[7] The war lasted for five weeks and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of settlers and the displacement of thousands more.[8] In the aftermath, the Dakota people were exiled from their homelands, forcibly sent to reservations in the Dakotas and Nebraska, and the State of Minnesota confiscated and sold all their remaining land in the state.[8] The war also ended with the largest mass execution in United States history with the hanging of 38 Dakota men.[8]

All four bands of eastern Dakota had been pressured into ceding large tracts of land to the United States in a series of treaties and were reluctantly moved to a reservation strip twenty miles wide, centered on Minnesota River.[8]: 2–3 There, they were encouraged by U.S. Indian agents to become farmers rather than continue their hunting traditions.[8]: 4–5 A crop failure in 1861, followed by a harsh winter along with poor hunting due to depletion of wild game, led to starvation and severe hardship for the eastern Dakota.[9] In the summer of 1862, tensions between the eastern Dakota, the traders, and the Indian agents reached a breaking point. On August 17, 1862, in a disagreement four young Dakota men killed five white settlers in Acton, Minnesota.[10] That night, a faction led by Chief Little Crow decided to attack the Lower Sioux Agency the next morning in an effort to drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley.[8]: 12 The demands of the Civil War slowed the U.S. government response, but on September 23, 1862, an army of volunteer infantry, artillery and citizen militia assembled by Governor Alexander Ramsey and led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley finally defeated Little Crow at the Battle of Wood Lake.[8]: 63 Little Crow and a group of 150 to 250 followers fled to the northern plains of Dakota Territory and Canada.[11][12]: 83

During the war, Dakota men attacked and killed over 500 white settlers, causing thousands to flee the area[13]: 107 and took hundreds of "mixed-blood" and white hostages, almost all women and children.[14][15] By the end of the war, 358(?) settlers had been killed, in addition to 77 soldiers and 36 volunteer militia and armed civilians.[16][17] The total number of Dakota casualties is unknown, but 150 Dakota men died in battle. On September 26, 1862, 269 "mixed-blood" and white hostages were released to Sibley's troops at Camp Release.[18] Interned at Fort Snelling, approximately 2,000 Dakota surrendered or were taken into custody,[19] including at least 1,658 non-combatants, as well as those who had opposed the war and helped to free the hostages.[15][13]: 233

In less than six weeks, a military commission, composed of officers from the Minnesota volunteer Infantry, sentenced 303 Dakota men to death. President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the convictions and approved death sentences for 39 out of the 303.[8]: 72 On December 26, 1862, 38 were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, with one getting a reprieve, in the largest one-day mass execution in American history. The United States Congress abolished the eastern Dakota and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) reservations in Minnesota, and in May 1863, the eastern Dakota and Ho-chunk imprisoned at Fort Snelling were exiled from Minnesota to a reservation in present-day South Dakota. The Ho-Chunk were later moved to Nebraska near the Omaha people to form the Winnebago Reservation.[20][8]: 76, 79–80 In 2012 and 2013, Governor Ramsey's 1862 call for the Dakota to "be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the State" was repudiated,[21][22] and in 2019, an apology was issued to the Dakota people for "150 years of trauma inflicted on Native people at the hands of state government."[23]

Background

Previous treaties

The eastern Dakota were pressured into ceding large tracts of land to the United States in a series of treaties negotiated with the U.S. government and signed in 1837, 1851 and 1858, in exchange for cash annuities, debt payments, and other provisions.[24][8]: 2 Under the terms of the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux signed on July 23, 1851, and Treaty of Mendota signed on August 5, 1851, the Dakota ceded large tracts of land in Minnesota Territory to the U.S. in exchange for promises of money and supplies.[25]: 1–4

The treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota committed the Dakota to live on a 20-mile (32 km) wide reservation centered on a 150 mile (240 km) stretch of the upper Minnesota River. During the ratification process, however, the U.S. Senate removed Article 3 of each treaty, which had defined the reservations. In addition, much of the promised compensation went to traders for debts allegedly incurred by the Dakota, at a time when unscrupulous traders made enormous profits on their trade. Supporters of the original bill said these debts had been exaggerated.[26]

Encroachments on Dakota lands and funds

When Minnesota became a state in 1858, representatives of several Dakota bands led by Little Crow traveled to Washington to negotiate about upholding existing treaties. Instead, they lost the northern half of the reservation along the Minnesota River in the resulting 1858 Dakota Treaty.[27] This loss was a major blow to the standing of Little Crow in the Dakota community.[28][29]

Meanwhile, the settler population in Minnesota Territory had grown to 172,072 in 1860, two years after statehood, from just 6,077 in 1850.[30] The land[which?] was divided into townships and plots for settlement. Logging and agriculture on these plots eliminated surrounding forests and prairies, which interrupted the Dakota's annual cycle of farming, hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice. Hunting by settlers dramatically reduced populations of wild game, such as bison, elk, deer and bear. This shortage of wild game not only made it difficult for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota to directly obtain meat, but also reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies.[29]

Although payments were guaranteed, the U.S. government was two months behind on both money and food when the war started because of men stealing food.[31][32] The Federal government was preoccupied by waging the Civil War.[33] Most land in the river valley was not arable, and hunting could no longer support the Dakota community. The Dakota became increasingly discontented over their losses: land, non-payment of annuities, because the Indian agents were late with the U.S. government annuity payments owed to the eastern Dakota,[9] past broken treaties, food shortages, and famine following crop failure. The traders refused to extend credit to the tribesmen for food, in part because the traders suspected the payments might not arrive at all due to the American Civil War.[9][34]: 116, 121 Tensions increased through the summer of 1862.[35]

On 1 January 1862 George E. H. Day (Special Commissioner on Dakota Affairs) wrote a letter to President Lincoln. Day was an attorney from Saint Anthony who had been commissioned to look into the complaints of the Sioux. He wrote:

- I have discovered numerous violations of law & many frauds committed by past Agents & a superintendent. I think I can establish frauds to the amount from 20 to 100 thousand dollars & satisfy any reasonable intelligent man that the indians whom I have visited in this state & Wisconsin have been defrauded of more than 100 thousand dollars in or during the four years past. The Superintendent Major Cullen, alone, has saved, as all his friends say, more than 100 thousand in four years out of a salary of 2 thousand a year and all the Agents whose salaries are 15 hundred a year have become rich.[31]

Day also accused Clark Wallace Thompson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Superintendency, of fraud.[36]

Negotiations

On August 4, 1862, representatives of the northern Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota bands met at the Upper Sioux Agency in the northwestern part of the reservation and successfully negotiated to obtain food. When two other bands of the Dakota, the southern Mdewakanton and the Wahpekute, turned to the Lower Sioux Agency for supplies on August 15, 1862, they were rejected. Indian Agent (and Minnesota State Senator) Thomas Galbraith managed the area and would not distribute food to these bands without payment.[citation needed]

At a meeting of the Dakota, the U.S. government and local traders, the Dakota representatives asked the representative of the government traders, Andrew Jackson Myrick, to sell them food on credit. His response was said to be, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung."[37] But the context of Myrick's comment at the time, early August 1862, is historically unclear.[38] Another version is that Myrick was referring to the Dakota women, who were already combing the floor of the fort's stables for any unprocessed oats to feed to their starving children, along with a little grass.[39]

The effect of Myrick's statement on Little Crow and his band was clear, however. In a letter to General Sibley, Little Crow said it was a major reason for commencing war:

"Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dying with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung."[40]

On August 16, 1862, the treaty payments to the Dakota arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota, and were brought to Fort Ridgely the next day. They arrived too late to prevent violence.[35]

War

Incident in Acton and aftermath

On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men on a hunting trip killed five settlers near a settlement in Acton Township, Minnesota.[41][13]: 81 Some accounts say that the men acted on a dare, following an argument about whether or not they should steal eggs.[13] Others say that the men were provoked when the farmer refused to give them food or water,[42]: 304 or liquor.[8]: 7 The victims included Robinson Jones, who ran a post office, lodge, and store, and four others, including his wife and 15-year-old adopted daughter.[8]: 7–9

Realizing that they were in trouble, the four men – Wahpeton men who had married Mdewakanton women – returned to Rice Creek village to tell their story to Red Middle Voice, the head of their band,[8] : 10 and Cut Nose, the "head soldier" of their lodge.[13] Red Middle Voice lobbied his nephew Chief Shakopee III for support, and together they traveled to Little Crow's village near the Lower Sioux Agency.[8]

In the middle of the night, a war council was convened at Little Crow's house, also including other Mdewakanton leaders such as Mankato, Wabasha, Traveling Hail, and Big Eagle.[8] The leaders were divided about the course of action to take; according to many accounts, Little Crow himself had initially been against an uprising and agreed to lead it only after an angry young brave called him a coward.[43][42]: 305 [44] By daybreak, Little Crow ordered an attack on the Lower Sioux Agency to take place that morning.[13]: 83

Historian Mary Wingerd disagrees with the modern terminology of calling it the Dakota war, stating it is "a complete myth that all the Dakota people went to war against the United States" and that it was instead "a faction that went on the offensive".[44] She estimates that fewer than 1,000 mostly Mdewakanton men out of a population of more than 7,000 Dakota were involved in the "Sioux uprising".[42]: 307 According to Wingerd, up to 300 Sissetons and Wahpetons may have joined in the fighting – only a fraction out of the 4,000 who lived near the Upper Sioux Agency – in defiance of their tribal elders, who opposed participation in what they warned would be a suicidal offensive.[42]

Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency

On August 18, 1862, Little Crow led a group in a surprise attack on the Lower Sioux (or Redwood) Agency. Trader Andrew Myrick was among the first who were killed.[42]: 305 Wounded, he escaped through an attic window, but was gunned down while running for the cornfields.[13]: 84 Myrick's severed head was later found with grass stuffed into his mouth,[13] in retaliation for Myrick's response, "Let them eat grass!" when asked weeks before if he was willing to extend credit to the Dakota when the government annuity payments had not arrived.[25]: 6, 12 Killing was suspended for a time while the attackers turned their attention to raiding the stores for flour, pork, clothing, whiskey, guns, and ammunition, allowing others to flee for Fort Ridgely, fourteen miles away.[13][45]: 109 A total of thirteen clerks, traders, and government workers were killed at the agency; another seven were killed as they fled; ten were taken captive; and approximately 47 people escaped.[45]: 111

B Company of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment sent troops from Fort Ridgely to quell the uprising, but were defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. Twenty-four soldiers, including the party's commander (Captain John Marsh), were killed in the battle.[46] Throughout the day, Dakota war parties swept the Minnesota River Valley and near vicinity, killing many settlers. Numerous settlements including the townships of Milford, Leavenworth and Sacred Heart, were surrounded and burned and their populations nearly exterminated.[47]

Captives

During the chaos of the initial attacks, some Dakota tried to warn their friends at the Lower Sioux Agency to flee.[48][34]: 136–138 Even those participating in the attacks made exceptions for who was killed.[34][42]: 305 Reverend Samuel Hinman later recounted that Little Crow himself had come to the Episcopal mission when the shootings started, glared at him, and left, allowing Hinman and his assistant Emily West to escape to Fort Ridgely.[34] George Spencer, a clerk in the trading store, credited Little Crow's head soldier Wakinyantawa (His Own Thunder) for saving his life by placing him under his protection.[34][49]

Spencer then became one of the few white men taken captive during the war; the rest of the captives were predominantly women and children.[15] A large number of captives were "mixed-blood" Dakota.[42] Although there were repeated threats against the lives of mixed-blood settlers,[34]: 142 even the most violent men exercised restraint when reminded that by killing mixed-blood Dakota, they would risk retribution from their victims' "full-blood" kinsmen.[42]: 306

The large number of captives taken in the early days of the conflict presented a dilemma for the Dakota war leaders. Big Eagle and others argued that they should be returned to the fort, but Little Crow insisted that they were valuable to the war effort and should be kept as hostages for their own protection.[34]: 140–141 While the captives were initially held by the soldiers who had captured them, as the days progressed, the logistics of feeding and taking care of the captives were divided up more broadly among families in Little Crow's encampment.[50][51]

The subject of the rape and abuse of captives during the Dakota War is controversial.[51] Of the white women and girls who were taken captive over the course of war, up to 40 were between the ages of twelve and forty.[13]: 190 Historian Gary Clayton Anderson states that nearly all of the young girls taken captive and most of the middle-aged women were forced into relationships which Dakota men perceived as "marriage".[13]: 191 He lists "the chance to obtain a wife" as one of the many different motives young Dakota men had for participating in the early days of the conflict, along with revenge, plunder, and the chance to gain honors in warfare.[13]: 211 There was at least one widely reported case of rape on the first evening of the conflict, August 18, 1862.[51] There were also three well documented cases of female captives who were "adopted" and protected by Dakota families from potential aggressors.[51]

Early Dakota offensives

Confident with their initial success, the Dakota continued their offensive and attacked the settlement of New Ulm, Minnesota, on August 19, 1862, and again on August 23, 1862. Dakota men had initially decided not to attack the strongly defended Fort Ridgely along the river, and turned toward the town, killing settlers along the way. By the time New Ulm was attacked, residents had organized defenses in the town center and were able to keep the Dakota at bay during the brief siege. Dakota men penetrated parts of the defenses and burned much of the town.[52] By that evening, a thunderstorm dampened the warfare, preventing further Dakota attacks.[citation needed]

Regular soldiers and militia from nearby towns (including two companies of the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, then stationed at Fort Ridgely) reinforced New Ulm. Residents continued to build barricades around the town.[53]

The Dakota attacked Fort Ridgely on August 20 and 22, 1862.[54][55] Although the Dakota were not able to take the fort, they ambushed a relief party from the fort to New Ulm on August 21. The defense at the Battle of Fort Ridgely further limited the ability of the American forces to aid outlying settlements. The Dakota raided farms and small settlements throughout south central Minnesota and what was then eastern Dakota Territory.[56][citation needed]

State military response

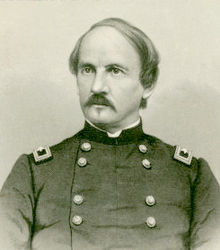

On August 19, 1862, Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey asked his long-time friend and political rival, former Governor Henry Hastings Sibley, to lead an expedition up the Minnesota River for the relief of Fort Ridgely, and gave him an officer's commission as Colonel of Volunteers.[8]: 31 Sibley had no previous military experience, but was familiar with the Dakota and the leaders of the Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Sisseton and Wahpeton bands, having traded among them since arriving in the Minnesota River Valley 28 years beforehand as a representative of the American Fur Company.[8][45]: 147–148

End of siege at Fort Ridgely

After receiving a message written by Lieutenant Timothy J. Sheehan about the seriousness of the attacks on Fort Ridgely, Colonel Sibley decided to wait for reinforcements, arms, ammunition and provisions before leaving St. Peter. On August 26, Sibley marched toward Fort Ridgely with 1400 men, including six companies of the 6th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 300 "very irregular cavalry".[57][8]: 31 On August 27, a vanguard of mounted men under Colonel Samuel McPhail arrived at Fort Ridgely and lifted the siege; the rest of Sibley's force arrived the next day and established a camp outside the fort. Many of the 250 refugees, some of whom had been confined within Fort Ridgely for eleven days, were transported to St. Paul on August 29.[57][58]

Militia units under Sibley's command to Fort Ridgely:[59]: 772, 781, 783, 784, 785, 790

- Captain William J. Cullen's mounted St. Paul Cullen Guards

- Captain Joseph F. Bean's company "The Eureka Squad"

- Captain David D. Lloyd's company organized in Rice County

- Captain Calvin Potter's company of mounted men

- Captain Mark Hendrick's battery of light artillery

- Captain J.R. Sterrett's company of mounted men raised at Lake City

Defense along southern and southwestern frontier

On August 28, Governor Ramsey sent Judge Charles Eugene Flandrau to the Blue Earth country to secure the state's southern and southwestern frontier, extending from New Ulm to the northern border of Iowa.[45]: 169 On September 3, Flandrau received his officer's commission as a colonel in Minnesota's volunteer militia. He set up his headquarters at South Bend, four miles southwest of Mankato, where he maintained a guard of 80 men.[60] Flandrau organized a line of forts, garrisoned by soldiers under his command, at New Ulm, Garden City, Winnebago, Blue Earth, Martin Lake, Madelia and Marysburg.[8]: 49 Flandrau and his companies were relieved on October 5, 1862, by the 25th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment.[45]: 170

Iowa Northern Border Brigade

In Iowa, alarm over the Dakota attacks led to the construction of a line of forts from Sioux City to Iowa Lake. The region had already been militarized because of the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857. After the 1862 conflict began, the Iowa Legislature authorized "not less than 500 mounted men from the frontier counties at the earliest possible moment, and to be stationed where most needed," though this number was soon reduced. Although no fighting took place in Iowa, the Dakota uprising led to the rapid expulsion of the few remaining unassimilated Dakota.[61][62]

Encounters in early September

Raids in Central Minnesota

After suffering defeats in the Minnesota River Valley, Little Crow split off from the main force and moved north into central Minnesota. On September 3, 1862, a detachment of the 10th Minnesota Infantry was attacked by Little Crow at the Battle of Acton and fell back to the fortified town of Hutchinson.[63] Unsuccessful sieges of the stockaded towns of Hutchinson and Forest City followed on September 4, but the Dakota left with many spoils including captured horses.[64]

Battle of Birch Coulee

On August 31, while Sibley trained new soldiers and waited for additional troops, guns, ammunition and food, he sent a group of 153 men on a burial expedition to find and bury dead settlers and soldiers, and ascertain what had happened to Captain John S. Marsh and his men during the attack at Redwood Ferry.[65]: 305 The company included members of the 6th Minnesota Infantry Regiment and mounted men of the Cullen Frontier Guards,[66] as well as teams and teamsters sent to bury the dead, accompanied by approximately 20 civilians who had asked to join the burial party. In the early morning hours of September 2, 1862, a group of 200 Dakota men surrounded and ambushed their campsite, kicking off a 31-hour siege known as the Battle of Birch Coulee, which continued until Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley finally arrived with more troops and artillery on September 3. The state military suffered its worst casualties during the war, with 13 soldiers dead on the ground, nearly 50 wounded, and more than 80 horses killed,[13]: 170 while only 2 Dakota soldiers were confirmed dead.[48]

Attacks in northern Minnesota and Dakota Territory

Farther north, the Dakota attacked several unfortified stagecoach stops and river crossings along the Red River Trails, a settled trade route between Fort Garry (now Winnipeg, Manitoba) and Saint Paul, Minnesota, in the Red River Valley in northwestern Minnesota and eastern Dakota Territory. Many settlers and employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and other local enterprises in this sparsely populated country took refuge in Fort Abercrombie, located in a bend of the Red River of the North about 25 miles (40 km) south of present-day Fargo, North Dakota. Between late August and late September, the Dakota launched several attacks on Fort Abercrombie; all were repelled by its defenders, including Company D of the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, which was garrisoned there, with assistance from other infantry units, citizen soldiers and "The Northern Rangers".[25]: 53–58

In the meantime, steamboat and flatboat traffic on the Red River came to a halt. Mail carriers, stage drivers and military couriers were killed while attempting to reach settlements such as Pembina, North Dakota; Fort Garry; St. Cloud, Minnesota; and Fort Snelling. Eventually, the garrison at Fort Abercrombie was relieved by a Minnesota Volunteer Infantry from Fort Snelling, and the civilian refugees were removed to St. Cloud.[67]:232-256

Army reinforcements

Due to the demands of the American Civil War, Adjutant General Oscar Malmros and Governor Alexander Ramsey of Minnesota had to repeatedly appeal for assistance from the governors of other northern states, the United States Department of War, and President Abraham Lincoln.[8]: 87 Finally, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton formed the Department of the Northwest on September 6, 1862 and appointed General John Pope, who had been defeated in the Second Battle of Bull Run, to command it, with orders to quell the violence "using whatever force may be necessary."[13]: 179–180 Pope reached Minnesota on September 16. Recognizing the severity of the crisis, Pope instructed Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley to move decisively, but struggled to secure additional Federal troops in time for the war effort.[68] Pope also requested "two or three regiments" from Wisconsin.[69] In the end, only the 25th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived on September 22, and was sent to defend temporary military posts along the "Minnesota frontier".[69]

Recruitment for the Minnesota infantry had restarted in earnest in July 1862, following President Lincoln's call for 600,000 volunteers to fight with the Union Army in the Civil War.[65]: 301–2 With the outbreak of war in Minnesota in August, the state adjutant general's headquarters ordered the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiments, which were still being constituted, to dispatch troops under Sibley's command as soon as companies were formed.[70][71]: 301, 349, 386, 416, 455 Many enlisted soldiers who had been furloughed until after harvest were quickly recalled, and new recruits were urged to enlist, furnishing their own arms and horses if possible.[65]: 302

Concerned that his troops lacked experience, Sibley urged Ramsey to hasten the return of the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment to Minnesota, following their humiliating surrender to the Confederates in the First Battle of Murfreesboro.[13]: 156 The enlisted men of the 3rd Minnesota were formally exchanged as paroled prisoners on August 28. Placed under the command of Major Abraham E. Welch, who had served as a lieutenant in the 1st Minnesota Infantry Regiment, they joined Sibley's forces at Fort Ridgely on September 13.[72]: 158

Battle of Wood Lake

The final decisive battle of the war took place at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862, and was a victory for the U.S. forces led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley. Following the arrival of more troops, guns, ammunition and provisions, Sibley's entire command had departed Fort Ridgely on September 19. According to one estimate, he had 1,619 men in his army, including the 270 men of the 3rd Minnesota, nine companies of the 6th Minnesota, five companies of the 7th Minnesota, one company of the 9th, 38 Renville Rangers, 28 mounted citizen guards, and 16 citizen-artillerists.[12] Sibley planned to meet Little Crow's men on the open plains above the Yellow Medicine River, where he believed his better organized, better equipped forces with their rifled muskets and artillery with exploding shells would have an advantage against the Dakota with their double-barreled shotguns.[73]

Meanwhile, Dakota runners were reporting Sibley's movements every few hours.[74] Chief Little Crow and his soldiers' lodge received word that Sibley's troops had reached the Lower Sioux Agency and would arrive at the area below the Yellow Medicine River around September 21. On the morning of September 22, Little Crow's soldiers' lodge ordered all able-bodied men to march south to the Yellow Medicine River.[15] While hundreds of soldiers marched willingly, others went because they had been threatened by the soldiers' lodge headed by Cut Nose (Marpiya Okinajin); they were also joined by a contingent from the "friendly" Dakota camp who sought to prevent a surprise attack on Sibley's army.[74][34]: 159 A total of 738 men were counted when they reached a point a few miles from Lone Tree Lake, where they had learned that Sibley had set up camp.[15] A council was called, and Little Crow proposed attacking and capturing the camp that night. However, Gabriel Renville (Tiwakan) and Solomon Two Stars argued vehemently against his plan, saying that Little Crow had underestimated the size and strength of Sibley's command, that attacking at night was "cowardly", and that his plan would fail because they and others would not help them.[75][76]

Upon learning that the army had thrown up breastworks to fortify the campsite, Rattling Runner (Rdainyanka) and the leaders of the "hostile" Dakota soldiers' lodge finally agreed that it would be unsafe to attack that night, and planned to attack Sibley's troops when they were marching on the road to the Upper Sioux Agency early in the morning.[48][76] On the night of September 22, Little Crow, Chief Big Eagle and others carefully moved their men into position under cover of darkness, often with a clear view of Sibley's troops, who were unaware of their presence.[48] Dakota fighters lay in the tall grass along the side of the road with tufts of grass woven into their headdresses for disguise, waiting patiently for daybreak when they expected the troops to march.[8][13]: 184

Much to the surprise of the Dakota, at about 7 am on September 23, a group of soldiers from the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment left camp in four or five wagons, on an unauthorized trip to forage for potatoes at the Upper Sioux Agency.[72] About half a mile from camp, after crossing the bridge over the creek to the other side of the ravine and ascending 100 yards into the high prairie, the lead wagon belonging to Company G was attacked by a squad of 25 to 30 Dakota men who sprang up and began shooting.[77][78][13] One soldier jumped out of the wagon and returned fire; the soldiers in the rear wagons started shooting; and the Battle of Wood Lake had begun.[77] Not waiting for orders or permission, Major Abraham E. Welch led 200 men from the 3rd Minnesota with a line of skirmishers to the left and the right following in reserve. They advanced to a point 300 yards beyond the stream, when an officer rode up to Major Welch with instructions from Colonel Sibley to fall back to camp. Welch obeyed reluctantly and the men of the 3rd Minnesota retreated down the slope towards the stream where they would sustain most of their casualties.[78]

Once the 3rd Minnesota had retreated across the creek, they were joined by the Renville Rangers, a unit of "nearly all mixed-bloods" under Lieutenant James Gorman, sent by Sibley to reinforce them.[13]: 185 The Dakota forces formed a fan-shaped line, threatening their flank.[73] Seeing that the Dakota were now passing down the ravine to try to outflank their men on the right, Sibley ordered Lieutenant Colonel William Rainey Marshall, with five companies of the 7th Minnesota Infantry Regiment and a six-pounder artillery piece under Captain Mark Hendricks, to advance to the north side of the camp; he also ordered two companies from the 6th Minnesota Infantry Regiment to reinforce them.[65] Marshall deployed his men equally in dugouts and in a skirmish line which fired as they gradually crawled forward and finally charged, successfully driving the Dakota back from the ravine.[79] On the extreme left, Major Robert N. McLaren led a company from the 6th Regiment around the south side of the lake to defend a ridge overlooking a ravine, and defeated a Dakota flanking attack on the other side.[65]

The Battle of Wood Lake ended after about two hours, as Little Crow and his men retreated in disorder.[73] Chief Mankato was killed in the battle by a cannonball.[8]: 62 Big Eagle later explained that hundreds of Dakota fighters were unable to get involved or fire a shot in the battle, because they had been positioned too far out.[48] Sibley decided not to pursue the retreating Dakota, mainly because he lacked the cavalry to do so.[8]: 64 On his orders, Sibley's men recovered and buried 14 fallen Dakota.[79][8]: 63 The exact Dakota losses are unknown but the fight effectively ended the war. Sibley lost seven men and another 34 were seriously wounded.[73]

Surrender at Camp Release

At Camp Release on September 26, 1862, the Dakota Peace Party handed over 269 former prisoners to the troops commanded by Colonel Sibley.[18] The captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (mixed-race) and 107 whites, mostly women and children, who had been held hostage by the "hostile" Dakota camp, which broke up as Little Crow and some of his followers fled to the northern plains. In the nights that followed, a growing number of Mdewakanton men who had participated in battles quietly joined the "friendly" Dakota at Camp Release; many did not want to spend winter on the plains and were persuaded by Sibley's earlier promise to punish only those who had killed settlers.[13]: 187

The surrendered Dakota men and their families were held while military trials took place from September to November 1862. Of the 498 trials, 303 men were convicted and sentenced to death.[8]: 72 President Lincoln commuted the sentences of all but 38.[80] A few weeks prior to the execution, the convicted men were sent to Mankato, while 1,658 Natives and "mixed bloods", including their families and the "friendly" Dakota, were sent to a compound south of Fort Snelling.[19]

Escape and death of Little Crow

Little Crow had fled northward on September 24, the morning after the Battle of Wood Lake, vowing never to return to the Minnesota River valley again. He and the Mdewakanton who followed him hoped to ally with the western Sioux – including the Yankton, Yanktonai and Lakota – and also hoped to gain support from the British in Canada, but received a mixed response.[34] Little Crow was turned away by Chief Standing Buffalo and the Sisseton north of Big Stone Lake, as well as the Yanktons to the southwest along the Missouri River.[16]: 62

Rebuffed by leaders of other tribes and accompanied by a dwindling number of his own followers, Little Crow eventually returned to Minnesota in late June 1863.[34] He was killed on July 3, 1863, near Hutchinson, Minnesota, while gathering raspberries with his teenage son, Wowinape. The pair were seen by Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey, who had been out hunting. Lamson and Little Crow exchanged fire, and Little Crow was mortally wounded by a ball in his breast.[8]: 83

Weeks later, when it was discovered that the body was that of Little Crow, Lamson received a $500 bounty from the state of Minnesota for his scalp.[34]: 178 In 1879, the Minnesota Historical Society put Little Crow's skeletal remains on display in the Minnesota State Capitol.[81] One notable objector to the display was former Lower Sioux Agency surgeon Dr. Asa Daniels, who wrote in 1908 that "Such a spectacle reflects sadly upon the humanity of Christian people."[82] Upon the request of Little Crow's grandson, Jesse Wakeman, his remains were removed from display in 1915, and finally returned to the family for burial in 1971 by historical archaeologist Alan Woolworth.[82][81] Wakeman noted on that day that the treatment of Little Crow's remains had "rankled" him and his people more than the way he had been killed.[82]

Chief Standing Buffalo led his band to the northern plains and Canada, where they wandered for nine years. After his death in an encounter with Gros Ventre in Montana, his son took the band into Saskatchewan. There they were ultimately given a reserve, where these northern Sisseton have stayed.[citation needed]

Aftermath

Trials

On September 27, 1862, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley ordered the creation of a military commission to conduct trials of the Dakota. One year later, the judge advocate general determined that Sibley did not have the authority to convene trials of the Dakota, due to his level of prejudice, and that his actions had violated Article 65 of the United States Articles of War. However, by then the executions had already occurred, and the American Civil War continued to distract the U.S. government.[83][13]: 214–215

The trials themselves were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and the officers who oversaw them did not conduct them according to military law. The 400-odd of trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Dakota represented by defense attorneys.[citation needed] Legal historian Carol Chomsky writes in the Stanford Law Review:

The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission composed completely of Minnesota settlers. They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings committed in warfare. The official review was conducted, not by an appellate court, but by the President of the United States. Many wars took place between Americans and members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war.[83]

The trials were also conducted in an atmosphere of extreme racist hostility towards the defendants expressed by the citizenry, the elected officials of the state of Minnesota and by the men conducting the trials themselves. By 3 November, the military commission had held trials of 392 Dakota men, with as many as 42 tried in a single day.[83] Not surprisingly, given the socially explosive conditions under which the trials took place, by 7 November the verdicts were in. The military commission announced that 303 Dakota prisoners had been convicted of murder and rape and were sentenced to death.[8]: 71

President Lincoln was informed by Maj. Gen. John Pope of the sentences on 10 November 1862 in a telegraphic dispatch from Minnesota.[83] His response to Pope was: "Please forward, as soon as possible, the full and complete record of these convictions. And if the record does not indicate the more guilty and influential, of the culprits, please have a careful statement made on these points and forwarded to me. Please send all by mail."[84]

When the death sentences were made public, Henry Whipple, the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and a reformer of U.S. Indian policy, responded by publishing an open letter. He also went to Washington, D.C. in the fall of 1862 to urge Lincoln to proceed with leniency.[85] On the other hand, General Pope and Minnesota Senator Morton S. Wilkinson warned Lincoln that the white population opposed leniency. Governor Ramsey warned Lincoln that, unless all 303 Dakota were executed, "[P]rivate revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians."[86]

Lincoln completed his review of the transcripts of the 303 trials with the help of two White House lawyers in under a month.[13]: 251 On December 11, 1862, he addressed the Senate regarding his final decision (as he had been requested to do by a resolution passed by that body on December 5, 1862):

- Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females. Contrary to my expectations, only two of this class were found. I then directed a further examination, and a classification of all who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles. This class numbered forty, and included the two convicted of female violation. One of the number is strongly recommended by the Commission which tried them for commutation to ten years' imprisonment. I have ordered the other thirty-nine to be executed on Friday, the 19th instant."[87]

In the end, Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 prisoners and allowed the execution of 39 men. However, "[on] December 23, [Lincoln] suspended the execution of one of the condemned men [...] after [General] Sibley telegraphed that new information led him to doubt the prisoner's guilt."[83] Thus, the number of condemned men was reduced to the final 38.[citation needed]

Even partial clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered white Minnesotans "reasonable compensation for the depredations committed."[citation needed] Republicans did not fare as well in Minnesota in the 1864 election as they had before. Ramsey (by then a senator) informed Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in a larger electoral majority. The President reportedly replied, "I could not afford to hang men for votes."[citation needed]

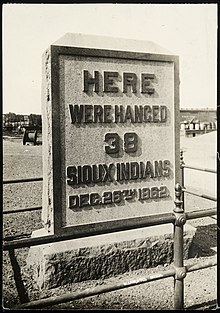

Execution

Companies D, E, and H of the 9th Minnesota, Companies A, B, F, G, H, and K 10th Minnesota and the 1st Minnesota Cavalry were part of the 2,000 man military guard[88] for the 38 prisoners hanged December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota.[89][90] It remains the largest single-day mass execution in American history. The size of the guard force was dictated by the numbers of angry Minnesotans encamped at Mankato and the concern of what they wanted to do to the prisoners not being hanged.[88]

The execution was public, on a square platform designed to drop from under the condemned. The gallows was built around the outside of the square with ten nooses per side. After the regimental surgeons pronounced the men dead, they were buried en masse in an unfrozen sand bar of the Minnesota River. Before they were buried, an unknown person nicknamed "Dr. Sheardown" possibly removed some of the prisoners' skin.[91] Despite having a large guard force posted at the grave-site, all of the bodies were exhumed and taken away the first night.[88]

At least three Dakota leaders escaped to Canada. In January 1864, Little Six and Medicine Bottle were captured, drugged, kidnapped and taken across the Canada–United States border to Fort Pembina, where they were arrested by Major Edwin A. C. Hatch.[92] Hatch's Independent Battalion of Cavalry took the two chiefs to Fort Snelling, where they were tried and later hanged in November 1865.[92][93][94] Little Leaf managed to evade capture.[citation needed]

Medical aftermath

Because of the high demand for cadavers for anatomical study, several doctors wanted to obtain the bodies after the execution. The grave was reopened in the night and the bodies were distributed among the doctors, a practice common in the era. William Worrall Mayo received the body of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ (Stands on Clouds), also known as "Cut Nose".[95] Mayo brought the body of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ to Le Sueur, Minnesota, where he dissected it in the presence of medical colleagues.[96]: 77–78 Afterward, he had the skeleton cleaned, dried and varnished. Mayo kept it in an iron kettle in his home office. His sons received their first lessons in osteology based on this skeleton.[96]: 167

In the late 20th century, the identifiable remains of Maȟpiya Akan Nažiŋ and other Dakota were returned by the Mayo Clinic to a Dakota tribe for reburial per the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The Mayo Clinic created a scholarship for a Native American student as apology for having misused the chief's body.[97][98]

Imprisonment

The remaining convicted Dakota were held in prison that winter. The following spring they were transferred to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa, where they were imprisoned from 1863 to 1866.[99][100] By the time of their release, one-third of the prisoners had died of disease. The survivors were sent with their families to Nebraska. Their families had already been expelled from Minnesota.[citation needed]

During their incarceration at Camp Kearney, the Dakota prison within Camp McClellan, Presbyterian missionaries attempted to convert the Dakota to Christianity and have them abandon their native cultural and spiritual beliefs and practices.[101][102]

In 1864, change of command at the camp allowed for a more lenient approach to the Dakota.[102] Using the general public's fascination to their advantage, they began to craft ornamental items, such as finger rings, bead work, wooden fish, hatchets, and bows and arrows, and sold them to support their needs within the internment camp, such as blankets, clothing, and food.[103] They also sent blankets, clothing, and money to their families who had been forcibly exiled to the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota.[103] In addition to packages, they maintained family ties communicating via postal mail. Profiteers exploited public bigotry by using the Dakota as spectacles, selling two-hour viewing sessions, forcing Dakota into public races with horses, and paying them for their dance ceremonies.[102][103]

During their incarceration, the Dakota continued to struggle for their rightful compensation of the lands ceded by treaty, as well as their freedom, even enlisting the help of sympathetic camp guards and settlers to assist. In April 1864, the imprisoned Dakota helped pay for missionary Thomas Williamson's trip to Washington, D.C. to argue in favor of the prisoners' release. He received a receptive audience in President Lincoln, but only a few Dakota were released, partially due to a proviso Lincoln had made with Minnesota congressmen who continued to refuse clemency.[103] The remaining Dakota were eventually released two years later by President Andrew Johnson, in April 1866. They, along with their families from the Crow Creek Reservation, were relocated to Santee Sioux Reservation in Nebraska.[101]

The United States Congress abolished the eastern Dakota and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) reservations in Minnesota and declared their treaties null and void. In May 1863, the eastern Dakota and Ho-chunk imprisoned at Fort Snelling were exiled from Minnesota. They were placed on riverboats and sent to a reservation in present-day South Dakota. The Ho-Chunk were also initially forced to the Crow Creek reservation, but later moved to Nebraska near the Omaha people to form the Winnebago Reservation.[20][8]: 76, 79–80

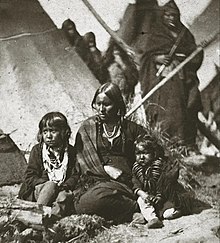

Pike Island internment

On November 7, 1862, the remaining 1,658 Dakota non-combatants – primarily women, children, and elders, but also 250 men – began a 150-mile journey from the Lower Sioux Agency to Fort Snelling.[19][42]: 319 They traveled in a wagon train that was four miles long, protected by only 300 soldiers under Lieutenant Colonel William Marshall.[42] Marshall urged The Saint Paul Daily Press to remind citizens living along their route that the Dakota they were escorting were "not the guilty Indians...but friendly Indians, women and children."[42]: 319, 396 When the caravan reached Henderson, however, an angry mob "armed with guns, knives, clubs and stones" overwhelmed the troops and attacked the Dakota, fatally injuring a baby.[42]: 320 They finally reached Fort Snelling on the evening of November 13, 1862.[19]

At first, they were settled in an open camp below Fort Snelling, but were soon relocated to a fenced stockade to protect them from further attacks.[42] Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious diseases such as measles struck the camp, killing an estimated 102 to 300 Dakota.[19] In April 1863, the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. The State issued a bounty of $25 per scalp on any Dakota male found free within the boundaries of the state to ensure their removal.[104] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who had remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict.[citation needed]

In May 1863, the surviving 1,300 Dakota were crowded aboard two steamboats and relocated to the Crow Creek Reservation, in Dakota Territory. At that time the place was stricken by drought making habitation difficult. In addition to those dying during the journey, more than 200 Dakota died within six months of arriving, many being the children.[105][106][107]

Firsthand accounts

Until 1894, most published accounts of the war were told from the point of view of European-American settlers and soldiers who had taken part in the war,[108] and to a lesser extent, the women who had been taken captive.[109][110] Many of these first-person narratives tended to focus on victim accounts of atrocities committed during the war.[111]

The first published narrative of the war told from the point of view of a Dakota leader who had fought in the uprising was compiled by historian Return Ira Holcombe in 1894. Holcombe interviewed Chief Big Eagle with the help of two translators.[108][48]

In 1988, historians Gary Clayton Anderson and Alan R. Woolworth published Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. The volume features excerpts from thirty-six Dakota narratives.[11] Many of the narratives come from "mixed-blood" eyewitnesses of events.[112] The narratives reflect a spectrum of views on the conflict, representative of factions within the Dakota community.[11]

Settler narratives

There are numerous firsthand accounts by European Americans of the wars and raids. For example, the compilation by Charles Bryant, titled Indian Massacre in Minnesota, included these graphic descriptions of the murders of settlers on the night of August 18, taken from an interview with Justina Kreiger about events she had not witnessed directly:[13]: 99

Mr. Massipost had two daughters, young ladies, intelligent and accomplished. These the savages murdered most brutally. The head of one of them was afterward found, severed from the body, attached to a fish-hook, and hung upon a nail. His son, a young man of twenty-four years, was also killed. Mr. Massipost and a son of eight years escaped to New Ulm.[67]: 141 The daughter of Mr. Schwandt, enceinte [pregnant], was cut open, as was learned afterward, the child taken alive from the mother, and nailed to a tree. The son of Mr. Schwandt, aged thirteen years, who had been beaten by the Indians, until dead, as was supposed, was present, and saw the entire tragedy. He saw the child taken alive from the body of his sister, Mrs. Waltz, and nailed to a tree in the yard. It struggled some time after the nails were driven through it! This occurred in the forenoon of Monday, 18th of August, 1862.[67]: 300–301

Although Mary Schwandt later disputed this lurid account of events based on discussions with her brother August Schwandt, who witnessed the killing of his family, the story of the nailing of children to fences and trees was repeated over and over again in Minnesota newspapers, by other survivors of the massacre, and by historians.[13]: 99, 303 Burial details burying victims of the killings also reported never finding such a child.[13]: 303

Newspaper editorials

S.P. Yeomans, editor of the Sioux City Register, c. May 30, 1863, wrote "with unflinching disregard for humankind"[113] an opinion piece complaining about the arrival in Iowa of Dakota women and children who had been exiled from Minnesota:[113]

The formerly favorite steamer, Florence," he wrote, "arrived at our levee on Tuesday; but instead of the cheerful faces of Capt. Throckmorten and Clerk Gorman we saw those of strangers; and instead of her usual lading of merchandise for our merchants, she was crowded from stem to stern, and from hold to hurricane deck with old squaws and papooses – about 1,400 in all – the non combative remnants of the Santee Sioux of Minnesota, en route to their new home….[114]

The Dakota have kept alive their own accounts of events suffered by their people.[115][116]

Continued conflict

After the expulsion of the Dakota, some refugees and Dakota men made their way to Lakota lands. Battles between the forces of the Department of the Northwest and combined Lakota and Dakota forces continued through 1864. In the 1863 operations against the Sioux in North Dakota, Colonel Sibley, with 2,000 men, pursued the Dakota into Dakota Territory. Sibley's army defeated the Lakota and Dakota in four major battles: the Battle of Big Mound on July 24, 1863; the Battle of Dead Buffalo Lake on July 26, 1863; the Battle of Stony Lake on July 28, 1863; and the Battle of Whitestone Hill on September 3, 1863. The Dakota retreated further, but faced Sully's Northwest Indian Expedition in 1864. General Alfred Sully led a force from near Fort Pierre, South Dakota, and decisively defeated the Dakota at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain on July 28, 1864 and at the Battle of the Badlands on August 9, 1864. The following year Sully's Northwest Indian Expedition of 1865 operated against the Dakota in Dakota Territory.[citation needed]

Conflicts continued. Within two years, settlers' encroachment on Lakota land sparked Red Cloud's War; the US desire for control of the Black Hills in South Dakota prompted the government to authorize an offensive in 1876 in the Black Hills War. By 1881, the majority of the Sioux had surrendered to American military forces. In 1890, the Wounded Knee Massacre ended all effective Sioux resistance.[citation needed]

Bounties

In reaction to raids by Dakota in southern Minnesota, on July 4, 1863 Governor Ramsey ordered the State adjutant general, Oscar Malmros to issue General Orders No. 41 initiating "volunteer scouts" who, providing their own arms, equipment, and provisions, patrolled from the town of Sauk Centre to the northern edge of Sibley County.[117] In addition to being paid two dollars a day, $25 bounties were offered for Dakota male scalps. On July 20, the original bounty order was amended to limit it to "hostile" men, instead of all Dakota males and scalps were no longer required. A bounty of $75 a scalp was offered to those not in military service; the amount was increased to $200 by Henry Swift Minnesota's new governor on September 22, 1863.[117] Newspapers during that time described the taking of many scalps, including that of Taoyateduta (Little Crow).[118] A total of $325 was paid out to four people collecting bounties.[117]

Minnesota after the war

During the war, at least 30,000 settlers fled their farms and homes in the Minnesota River valley and surrounding upland prairie areas.[16]: 61 One year later, no one had returned to 19 out of 23 counties that had been affected by the conflict.[16]

Following the American Civil War, however, the area was resettled. By the mid-1870s, it was again being used and developed by European Americans for agriculture.[citation needed]

The federal government re-established the Lower Sioux Indian Reservation at the site of the Lower Sioux Agency near Morton. It was not until the 1930s that the US created the smaller Upper Sioux Indian Reservation near Granite Falls.[citation needed]

Although some Dakota had opposed the war, most were expelled from Minnesota, including those who attempted to assist settlers. The Yankton Sioux Chief Struck by the Ree deployed some of his warriors to aid settlers, but he was not judged friendly enough to be allowed to remain in the state immediately after the war. By the 1880s, a number of Dakota had moved back to the Minnesota River valley, notably the Good Thunder, Wabasha, Bluestone and Lawrence families. They were joined by Dakota families who had been living under the protection of Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple and the trader Alexander Faribault.[citation needed]

By the late 1920s, the conflict began to pass into the realm of oral tradition in Minnesota. Eyewitness accounts were communicated first-hand to individuals who survived into the 1970s and early 1980s. The stories of innocent individuals and families of struggling pioneer farmers being killed by Dakota have remained in the consciousness of the prairie communities of south central Minnesota.[119] Descendants of the 38 Dakota killed, and their people, also remember the warfare and their people being dispossessed of their land and sent into exile in the west.[citation needed]

During the uprising the New Ulm Battery was formed under militia law to defend the settlement from the Dakota. That militia is the only Civil War era militia remaining in the United States today.[120] Many of the settlers in New Ulm had migrated from a German community in Ohio. In 1862, upon hearing of the uprising, their former neighbors in Cincinnati purchased a 10 Pound Mountain Howitzer and shipped to Minnesota.[120] General Sibley gave the battery one of the 6 pounders from Fort Ridgely. Today those guns are in the possession of the Brown County Museum.[120]

Repudiation of Ramsey's speech and apology to Dakota people

On August 16, 2012, Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton issued a proclamation calling for a Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation for the 150th anniversary of the Dakota War and also repudiating Governor Alexander Ramsey's calls for the Dakota people to be either exterminated or driven from the state when he addressed the Minnesota state legislature in September 1862; flags were also ordered to be flown at half-staff statewide.[121] Dayton declared, among other things, that "The viciousness and violence, which were commonplace 150 years ago in Minnesota, are not accepted or allowed now."[121] On May 2, 2013, Dayton again issued a repudiation Ramsey's September 1862 speech, which he claimed he was "appalled" by, and call for a Day of Reconciliation, which also involved flags being flow at half staff.[22] On December 26, 2019, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz issued an apology for the 1862 Mankato hangings and other acts against the Dakota people while participating in the annual Dakota 38+2 Memorial Ride and Run which was held at the site of the hangings.[23] Walz stated, among other things, that "On behalf of the people of Minnesota and as governor, I express my deepest condolences for what happened here, and our deepest apologies for what happened to the Dakota people" and that "While we can't undo over 150 years of trauma inflicted on Native people at the hands of state government, we can work to do everything possible to ensure that Native people are seen, heard, and valued today."[23]

Land returned

On February 12, 2021, the Minnesota government and Minnesota Historical Society transferred ownership of half of the lands near the Battle of Lower Sioux Agency to the Lower Sioux Community.[122][123][124] The Minnesota Historical Society owned approximately 115 acres of land while the state government owned near 114 acres.[122][124] About the return of their lands, Lower Sioux President Robert Larsen said, "I don't know if it's ever happened before, where a state gave land back to a tribe. [Our ancestors] paid for this land over and over with their blood, with their lives. It's not a sale; it's been paid for by the ones that aren't here anymore".[124]

Monuments and memorials

- Camp Release State Monument commemorates "the surrender of a large body of Indians and the release of 269 captives, mostly women and children" on September 26, 1862.[125] The monument credits "the signal victory over the hostile Sioux at Wood Lake by Minnesota troops under command of General Henry H. Sibley."[125] One of the other faces of the 51-foot granite monument is inscribed with the dates of battles that took place along the Minnesota River.[125]

- Wood Lake Battlefield State Monument, erected 1910, in memory of the U.S. soldiers who lost their lives in the Battle of Wood Lake.[126] Listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[127]

- Birch Coulee Battlefield in Morton, Minnesota features self-guided trails including historical markers telling the story of the battle from the perspectives of Captain Joseph Anderson for the U.S. and Chief Big Eagle (Wamditanka) for the Dakota.[128] The Birch Coulee State Monument honoring the officers and soldiers of the 6th Minnesota, the Cullen Frontier Guards and other detachments is approximately two miles away.[129][130]

- Faithful Indians' Monument, adjacent to the Birth Coulee State Monument, erected in 1899 to honor "full-blood" Dakota who had remained "unwaveringly loyal and who had saved the life of at least one white person."[57] Among the six Dakota named on the monument are John Other Day (Ampatutokicha), who helped 62 settlers escape to safety at the start of the conflict, and Snana (Maggie Brass), who took teenage captive Mary Schwandt under her protection during the war.[57][11]

- Fort Ridgely State Monument, erected in 1896, commemorates the soldiers and citizens who defended the fort during the siege (August 18–27, 1862). Listed on the monument are members of Companies B and C of the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, the Renville Rangers, armed citizens led by Benjamin H. Randall, and "a number of women who cheerfully and bravely assisted in the defense of the Fort."[131]

- Henderson Monument, dedicated to the memory of five members of the Henderson family. Erected in 1907 by the Renville County Pioneers, it was originally located in Beaver Falls Township, where they were killed. Moved to its current location near Morton by the Renville County Historical Society in 1981.[132][133]

- Radnor Erle Monument, in the Morton Pioneer Monuments Roadside Parking Area, four miles north of Morton, Minnesota, along U.S. highway 71.[134] Erected in 1907 as a memorial to Erle, who was killed on August 18, 1862, saving his father's life.[135]

- Schwandt State Monument, in Renville County, Minnesota, on County Road 15 near Timms Creek.[136] Erected in 1915 to memorialize six members of the Schwandt family and one family friend who were killed.[134]

- Redwood Ferry Monument, honors Captain John Marsh, U.S. Interpreter Peter Quinn, and 24 men who died at the ambush on August 18.[137] The granite monument was erected by the Minnesota Valley Historical Society on the site of the old ferry landing,[138] on the north side of the Minnesota River,[137] which was largely inaccessible and on private property.[139] There is a roadside marker located on a bluff above the site along state Highway 19 between Morton and Franklin, Minnesota.[134]

- Defenders State Monument, Center Street, New Ulm. Erected in 1890 by the State of Minnesota to commemorate the two battles fought in New Ulm in 1862.[134] The monument recognizes the citizens of Blue Earth, Nicollet, and Le Sueur Counties who came to the aid of their neighbors in Brown County.[140] The artwork at the base was created by New Ulm artist Anton Gag.[134]

- The "Hanging Monument" in Mankato, Minnesota, was a four-ton granite marker that read "Here Were Hanged 38 Sioux Indians: Dec. 26th, 1862."[141][42]: 333 It was erected in 1912 by two Dakota War veterans, Judge Lorin Cray and General James H. Baker, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of "the city's most significant event".[142] It originally stood in a grassy plot near the site of the mass execution of 38 Dakota men, but was moved in 1965 to the other side of a gas station, facing the main bridge into town.[142] In 1971, the City of Mankato removed the monument altogether in response to American Indian Movement (AIM) leaders,[142] as well as local citizens pushing for Mankato's designation as an "all American town" by the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission.[141] In the mid-1990s, it disappeared from a city storage yard at Sibley Park,[143] where it had been half-buried under sand.[142] Its current whereabouts are unknown.[143][141]

- Reconciliation Park near downtown Mankato, dedicated in 1997 "to promote healing between Dakota and non-Dakota peoples."[144] The park features a 67-ton statue of a buffalo by local sculptor Tom Miller and a large boulder with a quote from the late Dakota spiritual leader, Amos Owen.[142] In 2012, the "Dakota 38" memorial was unveiled, listing the names of the 38 men who were executed there.[145][144]

- Acton State Monument, erected in 1909 to mark the location where the first blood was shed on August 17, 1862.[146] Next to the monument, the Acton Incident historical marker – updated by the Minnesota Historical Society in 2012 – serves as a memorial to the five settlers who were murdered by four teenage hunters, on the eve of the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862.[147]

- Guri Endreson-Rosseland State Monument in the Vikor Lutheran Cemetery near Willmar, Minnesota. Dedicated to Mrs. Guri Enderson-Rosseland, who survived an attack at her home, and, in the following days, traveled the countryside assisting wounded settlers.[148]

- White Family Monument, near Brownton, Minnesota. All four members of the White family were killed on September 22 at their home on Lake Addie. The monument stands near the site of their home.[149]

- Lake Shetek State Park monument, to 15 white settlers killed there and at nearby Slaughter Slough on August 20, 1862[150][151]

- A stone monument with a plaque was erected in 1929 near the spot in Meeker County where Little Crow (Taoyateduta) was killed by Nathan Lamson.[152]

- West Lake Attack monument, in Lebanon Lutheran Cemetery, Peace Lutheran Church, New London, Minnesota. Dedicated to 13 white settlers of the Broberg and Lundborg families killed on August 20, 1862. [56]

Commemorative events

- The annual Mankato Pow-wow, held in September, commemorates the lives of the executed men.[153]

- Several memorial rides have taken place over the years since the executions. In 2012, for the 150th anniversary of the executions, the Dakota and Lakota memorial ride led by Jim Miller (Dakota) rode on horseback from Brule, South Dakota, reaching Mankato on the day of the anniversary.[44]

In popular media

- In the Laura Ingalls Wilder novel, Little House on the Prairie (1935), Laura asks her parents about the Minnesota massacre, but they refuse to tell her any details.[154]

- Frederick Russell Burnham begin Scouting on Two Continents with a description of his house being burned by the Dakota in 1862 while the baby Frederick survives hidden in a basket of corn husks in a field[155]

- The uprising plays an important role in the historical novel The Last Letter Home (1959) by the Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg. It was the fourth novel of Moberg's four-volume The Emigrants epic. These were based on the Swedish emigration to American and the author's extensive research in the papers of Swedish emigrants in archival collections, including the Minnesota Historical Society.[citation needed]

- These novels were adapted as the Swedish films The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972), both directed by Jan Troell. The latter film particularly portrays the period of the Dakota Wars and the historical mass execution. Stephen Farber of The New York Times said "its portrait of the Indians is one of the most interesting ever caught on film" and this is "an authentic American tragedy".[156]

- Poet Layli Long Soldier's poem "38" is about the massacre and was first published in Mud City Journal and later collected in her 2017 book Whereas.[157][158]

- In 2007, Minnesota House of Representatives member Dean Urdahl published his historical fiction novel "Uprising" about the events of 1862 followed by the sequels "Retribution" in 2009 and "Pursuit" in 2011.[159][160]

- The Lost Wife, an historical fiction book published in 2023, recounts the story of a woman who travels west, marries, and tries to flee with her children when the uprising begins.

Several works were completed that marked the 150th anniversary of the mass execution:

- The This American Life episode "Little War on the Prairie" (aired November 23, 2012) discusses the continuing legacy of the conflict and mass executions in Mankato, Minnesota, marking the 150th anniversary of the events.[44]

- The Past Is Alive Within Us: The U.S.–Dakota Conflict (2013) is a video documentary examining Minnesota's involvement in the Dakota War during the Civil War, which had its major battlefields in the East. It provides both historical information and contemporary stories.[161]

- Dakota 38 (2012) is an independent film by Silas Hagerty, which documents the annual long-distance, commemorative horseback journey, led by Jim Miller (Dakota), by a group of Dakota, Lakota, and their supporters in honor of the ancestors. In 2008 the event was filmed as they rode from Lower Brule, South Dakota, over 330 miles to reach Mankato, Minnesota on the anniversary of the mass execution. They made the ride and the film "to encourage healing and reconciliation."[162][163][164]

See also

- Fort Ridgely State Park

- Monson Lake State Park

- Upper Sioux Agency

- We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee

- List of Indian massacres

- American Indian Wars

- People

- Sarah F. Wakefield, captive

- We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee (Chaska), Dakota man who held or protected Wakefield

References

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862–1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2726-0.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862–1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2726-0.

- ^ Wingerd, p. 400 n 4.

- ^ Satterlee, Marion (1923). Outbreak and massacre by the Dakota Indians in Minnesota in 1862 : Marion P. Satterlee's minute account of the outbreak, with exact locations, names of all victims, prisoners at Camp Release, refugees at Fort Ridgely, etc. : complete list of Indians killed in battle and those hanged, and those pardoned at Rock Island, Iowa : interesting items and anecdotes. Minneapolis, MN: M.P. Satterlee. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7884-1896-9. OCLC 48682232.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862–1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2726-0.

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862–1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7864-2726-0.

- ^ "During the War". The US–Dakota War of 1862. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- ^ a b c Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota (2010) p. 302.

- ^ "The Acton Incident". The US–Dakota War of 1862. February 27, 2013. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Gary Clayton; Woolworth, Alan R., eds. (1988). Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 2, 4, 120, 141, 268. ISBN 978-0-87351-216-9.

- ^ a b Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Anderson, Gary Clayton (2019). Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-6434-2

- ^ "During the War". The US–Dakota War of 1862. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Samuel J. (1897). "Chapter IX, Narrative 1 (Samuel J. Brown's Recollections)". Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press (published 1988). pp. 222–223, 225. ISBN 978-0-87351-216-9.

- ^ a b c d Clodfelter, Micheal (1998). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862–1865. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-2726-4.

- ^ Wingerd, North Country (2010) p. 400 n 4.

- ^ a b "Camp Release". The US–Dakota War of 1862. July 13, 2012. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. (2005). Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. Prairie Smoke Press. pp. 9, 30, 37, 57. ISBN 978-0-9772718-1-8.

- ^ a b "Ho-Chunk and Blue Earth, 1855–1863". MNopedia. September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Nelson, Emma (August 16, 2012). "Dayton declares remembrance of U.S.–Dakota War". MN Daily. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "Dayton repudiates Ramsey's call to exterminate Dakota". Star Tribune. May 2, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Dakota Governor Walz makes historic apology for 1862 mass hanging in Mankato". Indian Country Today. January 2, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Clemmons, Linda (2005). "'We Will Talk of Nothing Else': Dakota Interpretations of the Treaty of 1837". Great Plains Quarterly. 186 – via Digital Commons – University of Nebrasksa – Lincoln.

- ^ a b c Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (2nd ed.). Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0873511032.

- ^ Gary Clayton Anderson, Massacre in Minnesota(2019) pp. 31–32, 50.

- ^ "Treaty with the Sioux, 1858". treaties.okstate.edu. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Babcock, W.M. (1962). "Minnesota's Indian War" (PDF). Minnesota History. 38 (3): 93–98. JSTOR 20176455. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Russo, P.A. (1976). "The Time to Speak Is over: The Onset of the Sioux Uprising" (PDF). Minnesota History. 45 (3): 97–106. JSTOR 20178433. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2023. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- ^ "Minnesota Territory, 1857". The US–Dakota War of 1862. September 2, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Day, George E.H. (January 1, 1862). "Report on Indian affairs in Minnesota". Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. Washington DC. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ Reminiscences of Little Crow, An address at the Annual Meeting of the Minnesota Historical Society, Dr. Asa W. Daniels, January 21, 1907, Library of Congress [1]

- ^ Douglas S. Benson (1996). Presidents at War: A Survey of United States Warfare History in Presidential Sequence 1775–1980. p. 328.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Anderson, Gary Clayton (1986). Little Crow: Spokesman for the Sioux. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-196-4.

- ^ a b "The Dakota Conflict (Sioux Uprsing) Trials of 1862". law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Thompson, Clark Wallace," MNOPEDIA Minnesota Historical Society, Colin Mustful, July 2019 [2]

- ^ Dillon, Richard H. (1920). North American Indian Wars. City: Booksales. p. 126.

- ^ Michno, Gregory (November 5, 2012). "10 Myths on the Dakota Uprising". (2012). True West Magazine. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Gary (1983). "Myrick's Insult: A fresh look at Myth and Reality" (PDF). Minnesota History. 48 (5). Minnesota Historical Society: 198–206. JSTOR 20178811. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Letter from Little Crow to Col. Henry Sibley (September 7, 1862) AG Report, 35–36

- ^ "Timeline". Minnesota Historical Society (U.S.–Dakota War of 1862). March 12, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wingerd, Mary Lethert (2010). North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Delegard, Kirsten. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1452942605. OCLC 670429639.

- ^ "Taoyateduta Is Not a Coward" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. September 1962. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "479: Little War on the Prairie". This American Life. April 15, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Folwell, William Watts (1921). A History of Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- ^ Anderson, Little Crow, 130–39; Schultz, Over the Earth I Come, 48–58; Heard, History of the Sioux War, 73; Board of Commissioners, Minnesota in the Civil War, 2:112–114, 166–181.

- ^ Nixon, Barbara (2012). Mi' Taku'ye-oyasin : Letters from Wounded Knee : the native American Holocaust. Bloomington, Indiana. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4653-5391-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f Big Eagle, Jerome; Holcombe, Return Ira (July 1, 1894). "A Sioux Story of the War: Chief Big Eagle's Story of the Sioux Outbreak of 1862". St. Paul Pioneer Press.

- ^ Bishop, Harriet E. (1864). Dakota War Whoop: Indian Massacres and War in Minnesota, 1862–3. Saint Paul: William J. Moses' Press.

- ^ Diedrich, Mark (1995). Old Betsey: The Life and Times of a Famous Dakota Woman and Her Family. Rochester, New York: Coyote Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0961690199.

- ^ a b c d Zeman, Carrie Reber; Derounian-Stodola, Kathryn Zabelle, eds. (2012). A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity: Dispatches from the Dakota War. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 66, 274, 300. ISBN 978-0-8032-3530-4.

- ^ Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co. p. 2 (autobiographical account). ASIN B000F1UKOA.

- ^ Tolzmann, Don Heinrich (February 9, 2024). Memories of the Battle of New Ulm. Heritage Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7884-1863-1.

- ^ Soldiers: 3 killed/13 wounded; Lakota: 2 known dead.

- ^ "Ft. Rid". The Dakota Conflict of 1862: Battles. Mankato Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Wilcox, Joan Paulson (March 29, 2013). "The West Lake Attack". The U.S.–Dakota War of 1862.

- ^ a b c d Folwell, William Watts (1921). A History of Minnesota. Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 149–150, 390–391.

- ^ Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 26, 31. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.