Contents

Fort Union National Monument is a unit of the National Park Service of the United States, and is located north of Watrous in Mora County, New Mexico. The national monument was founded on June 28, 1954.

The site preserves the second of three forts constructed on the site beginning in 1851, as well as the ruins of the third. Also visible is a network of ruts from the Mountain and Cimarron Branches of the old Santa Fe Trail.[5]

There is a visitor center with exhibits about the fort and a film about the Santa Fe Trail. The altitude of the Visitor Center is 6760 feet (2060 m). A 1.2-mile (1.9-kilometre) trail winds through the fort's adobe ruins.

Description by William Davis

Santa Fe trader and author William Davis gave his first impression of the fort in the year 1857:

Fort Union, a hundred and ten miles from Santa Fé, is situated in the pleasant valley of the Moro. It is an open post, without either stockades or breastworks of any kind, and, barring the officers and soldiers who are seen about, it has much more the appearance of a quiet frontier village than that of a military station. It is laid out with broad and straight streets crossing each other at right angles. The huts are built of pine logs, obtained from the neighboring mountains, and the quarters of both officers and men wore a neat and comfortable appearance.[6]

History of Fort Union

The fort was established in the New Mexico Territory, on the Santa Fe Trail.[7] It was provisioned in large part by farmers and ranchers of what is now Mora County (formally created in 1860), including the town of Mora, where the grist mill established by Ceran St. Vrain in 1855 produced most of the flour used at the fort. There were three different Fort Unions, the first was created in 1851 and lasted until 1861, the second was created in 1861 and lasted until 1862, and the third was created in 1862 and lasted until 1891.[8]

Fort Union and its creation was a shift in the use of monetary funds for defense, as well as to provide more efficient protection in the region at the time. The secretary of war at the time, C.M. Conrad, wrote a letter to Lt. Col. Edwin V. Sumner detailing these changes, this was the beginning of a complete reset of the structure of troops positioning in the area.[9]

The first Fort Union was constructed to provide protection for travelers and people living in the vicinity along the Santa Fe Trail from hostile Indigenous Tribes. The first fort was built and was labeled a "frontier fort" which is described as more open campuses, places to house and feed soldiers, rather than a traditional defense structure.[8] In the early days, the Utes and Jicarilla Apaches occupied the area around the fort and were the predominant tribes that kept soldiers constantly employed.[10]

The second Fort Union was the more traditional defense structure out of the three. It was built with the specific purpose of defending against an invasion of Confederate forces. The fort was built in less than a year. After completion in 1862 Fort Union was one of the last lines of defense between Confederate forces in Santa Fe and the extremely valuable mineral resources located in Colorado. Soldiers from Fort Union united with volunteer forces from Colorado to push back the Confederates in the Battle of Glorieta Pass.[11]

The third Fort Union was not unlike the first in the sense that it was a frontier fort and not created for defense, but it was mainly used as a supply base to hold and distribute different types of goods such as ammunition, food, clothing, etc. The third Fort Union is what you can tour today, it is made with native materials such as clay stone, and lumber, adobe brick was used for the walls and was coated in plaster (nps.gov).[8] The fort was abandoned by the military due to the conclusion of the American Indian Wars and the formation of the Santa Fe Railroad.

The fort served as the headquarters of the 8th Cavalry in the early 1870s and as the headquarters of the 9th Cavalry in the late 1870s during the Apache Wars.[12]

Land ownership

In its forty years (1851–1891) as a frontier post, Fort Union had to defend itself in the courtroom as well as on the battlefield. When the United States Army built Fort Union in the Mora Valley in 1851, the soldiers were unaware that they had encroached on private property, which was part of the Mora Grant. The following year Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner expanded the fort to an area of eight square miles by claiming the site as a military reservation. In 1868, President Andrew Johnson declared a timber reservation, encompassing the entire range of the Turkey Mountains (part of the Sangre de Cristo range) and comprising an area of fifty-three square miles, as part of the fort.[13]

The claimants of the Mora Grant immediately challenged the government squatters and took the case to court. By the mid-1850s, the case reached Congress. In the next two decades, the government did not give any favorable decision to the claimants, until 1876 when the Surveyor-General of New Mexico reported that Fort Union was "no doubt" located in the Mora Grant. But the army was unwilling to move to another place or to compensate the claimants because of the cost. The Secretary of War took "a prudential measure", protesting the decision of the acting commissioner of the General Land Office. He argued that the military had improved the area and should not give it up without compensation.[13] This stalling tactic worked; the army stayed at the fort until its demise in 1891, not paying a single penny to legitimate owners.

Gallery

-

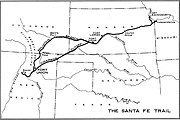

Map of the historic Santa Fe Trail

-

Remainder of buildings along Officer's Row

-

Remainder of the fort's hospital

-

View of the fort from a distance away

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Mora County, New Mexico

- List of national monuments of the United States

References

- ^ "Fort Union National Monument". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ "Annual Report of Lands as of September 30, 2011" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Cultural Encounters at Fort Union

- ^ William H. Davis, El Gringo − or New Mexico and Her People, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York 1857 (online at: El Gringo Archived 2006-09-18 at the Wayback Machine), p. 51

- ^ Leo E. Oliva. FORT UNION AND THE FRONTIER ARMY IN THE SOUTHWEST: A Historic Resource Study Fort Union National Monument. Professional Papers No. 41, Division of History National Park Service Fort Union, New Mexico. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Southwest Cultural Resources Center, 1993.

- ^ a b c "History & Culture - Fort Union National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ Utley, Robert (1965). Fort Union National Monument, New Mexico. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Stanley, F. (1953). Fort Union (New Mexico). p. 49.

- ^ "Fort Union National Monument". npshistory.com. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ^ Schubert, Frank N. (1997). Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870-1898. Scholarly Resources Inc. p. 41. ISBN 9780842025867.

- ^ a b U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Military Affairs, "Title to Certain Military and Timber Reservations", Senate Report 621, 45th Congress, 3rd Session, 1879, pp. 3-4