Contents

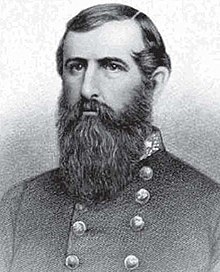

John Clifford Pemberton (August 10, 1814 – July 13, 1881) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole Wars and with distinction during the Mexican–American War. He resigned his commission to serve as a Confederate lieutenant-general during the American Civil War. He led the Army of Mississippi from December 1862 to July 1863 and was the commanding officer during the Confederate surrender at the Siege of Vicksburg.

Early life and career

Pemberton was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the second child of John and Rebecca Clifford Pemberton. His ancestor, Phineas Pemberton, traveled to the Colony of Pennsylvania from Lancashire, England along with William Penn in 1682.[1] John entered the United States Military Academy in 1833 and was a roommate and close friend of George G. Meade.[2] He graduated in 1837, standing 27th in his class out of 50 cadets.[3] He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Artillery Regiment on July 1, 1837. He participated with the 4th during the U.S. Army actions against the Seminole Indian tribe during the Second Seminole War in 1837 and 1838, fighting in Florida at the Battle of Loxahatchee on January 24, 1838.[4]

Pemberton and the 4th Artillery served in garrison duty at Fort Columbus, Governors Island, New York from 1838 to 1839, and then at the Camp of Instruction located near Trenton, New Jersey in 1839. He then served along the northern U.S. frontier during the brief Canadian Border Disturbances of the Aroostook War. Pemberton and the 4th were next stationed in Michigan, serving at Detroit in 1840, at Fort Mackinac in the upper Great Lakes in Michigan in 1840 and 1841, and at Fort Brady in 1841. He then served in Buffalo, New York, from 1841 to 1842, and was promoted to first lieutenant on March 19, 1842. Pemberton and the 4th returned to garrison duty at Fortress Monroe, in Hampton Roads harbor on coastal Virginia in 1842, then were stationed at the U.S. Army Cavalry School at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, in 1842 and 1843, and returned to Fort Monroe from 1844 to 1845.[4]

Mexican-American War

From 1845 to 1846, Pemberton and the 4th Artillery were part of the U.S. military occupation of Texas before the admission of the Republic of Texas into the United States as the 28th state in 1845. Then the 4th was sent to Mexico at the start of the Mexican–American War the following year. He fought at the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846, and at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma the next day. He then fought well at the Battle of Monterrey in that fall and was appointed a brevet captain "for Gallant Conduct in the several Conflicts at [Monterrey]" on September 23.[4]

Pemberton then fought in the U.S. Army's 1847 actions in Mexico, including the Siege of Vera Cruz in March, the Battle of Cerro Gordo in April, the skirmish near Amazoque in May, the capture of San Antonio and the Battle of Churubusco in August, and most notably in the Battle of Molino del Rey that September. Pemberton was appointed a brevet major[5] for his performance at Molino del Rey on September 8. He then was part of the storming of Chapultepec Castle on September 13, and the Battle for Mexico City that day and the next,[4] where Pemberton was wounded.[3] Pemberton held the position of Aide-de-Camp to Brevet Brigadier General William J. Worth from August 4, 1846, to May 1, 1849, and was a fellow staff lieutenant in the same division as his future opponent in the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant.[4] He was an original member of the Aztec Club of 1847 – a military society founded by U.S. Army officers who served in Mexico City during the military occupation following the war.

After Mexican-American War

In 1848, Pemberton married Martha Thompson of Norfolk, Virginia.[6]

After the war with Mexico, Pemberton and the 4th Artillery served in garrison duty at Fort Pickens near Pensacola, Florida, in 1849. He then fought in Florida during hostilities against the Seminoles in 1849 and 1850. The 4th returned to garrison duty at New Orleans Barracks in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1850, and Pemberton was promoted to captain on September 16. He next served in Fort Washington, Maryland, along the lower Potomac River below the capital in 1851 and 1852, at Fort Hamilton, New York, from 1852 to 1856. He and the 4th Artillery fought again in Florida during further hostilities against the Seminoles from 1856 to 1857.[4]

Pemberton and the 4th were then on frontier duty at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, from 1857 to 1858, and participated in the Utah War in 1858. He was then stationed at Fort Kearny in the New Mexico Territory in 1859, at Fort Ridgely in Minnesota from 1859 to 1861. After returning from the West in April 1861, he passed through Baltimore during the infamous Baltimore riot of 1861 in command of a regiment in transit on April 18–19, 1861, en route to Fort McHenry. Later he was briefly on garrison duty at the Washington Arsenal in Washington, D.C., in April 1861.[4]

American Civil War

At the start of the American Civil War in 1861, Pemberton resigned from his commission in the United States Army and joined the Confederate States Army, despite his birth in a free state and the fact that his two younger brothers both fought for the United States. He resigned his commission, effective April 29, despite pleas from his family and his former commander Winfield Scott.[3] His decision was due to the influence of his Virginia-born wife and many years of service in the slave states before the war.[7] He was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Army of the Confederate States of America (ACSA) on March 28, and was made assistant adjutant general of the forces around and in the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on April 29, the date of his resignation from the U.S. Army. He was promoted to colonel on May 8. On May 9, Pemberton took a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Artillery of the Provisional Army of Virginia.[8] Upon the absorption of the Provisional Army of Virginia into the PACS, Pemberton was appointed a major of artillery, a line field commission, on June 15, 1861, and was quickly promoted to brigadier general two days later. His first brigade command was in the Department of Norfolk, Virginia, leading its 1st Brigade from June to November.[3]

Pemberton was promoted to major general on January 14, 1862, and given command of the Confederate Department of South Carolina and Georgia, an assignment lasting from March 14 to August 29,[3] with his headquarters in Charleston, South Carolina. As a result of Pemberton's abrasive personality, his public statement that if he had to make a choice, he would abandon the area rather than risk the loss of his outnumbered army,[9] and the distrust of his free-state birth, the governors of both states in his department petitioned President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis for his removal. Davis needed a commander for a new department in Mississippi and also a command for Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, so he sent Pemberton west and assigned the more popular Beauregard to Charleston.[10]

Vicksburg

On October 10, 1862, Pemberton was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general,[3] and assigned to defend the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the Mississippi River, known as the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. Davis gave him the following instructions regarding his new assignment: "... consider the successful defense of those States as the first and chief object of your command." Pemberton arrived at his new headquarters in Jackson, Mississippi, on October 14.[11]

His forces consisted of fewer than 50,000 men under the command of Maj. Gens. Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price, with around 24,000 in the permanent garrisons at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana.[10] John D. Winters described the men under Pemberton as "a beaten and demoralized army, fresh from the defeat at Corinth, Mississippi."[11] Pemberton faced his former Mexican War colleague, the aggressive U.S. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and over 70,000 U.S. soldiers in the Vicksburg Campaign.

In an attempt to carry out his orders from both Davis and Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, Pemberton and his Army of Mississippi set out east to combine with Johnston's forces gathering around Jackson while remaining in contact and covering Vicksburg. Another order from Johnston changing their proposed meeting location caused Pemberton to turn around. When he did, he accidentally collided with Grant's army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16 and suffered a significant defeat. Pemberton retreated to the Big Black River, where he fought and suffered even more heavy losses on May 17.[12] Pemberton resolved to defend Vicksburg and led his defeated men back into its defenses on May 18. In the process, he gave up the high ground on Hayne's Bluff, which Sherman had failed to take in December. Johnston had advised him that if this ground ever fell, Vicksburg would be untenable and that he should escape with his army of 31,000, sacrificing the city. Pemberton refused to take this advice.[13] He held firm for over six weeks while soldiers and civilians were starved into submission. (Pemberton, well aware of his reputation as a Northerner by birth, was probably influenced by his fear of public condemnation as a traitor if he abandoned Vicksburg.)

On the evening of July 2, 1863, Pemberton asked in writing his four division commanders if they believed their men could "make the marches and undergo the fatigues necessary to accomplish a successful evacuation" after 45 days of siege. With four votes of no, the next day, Pemberton asked the U.S. soldiers for an armistice to allow time for the discussion of terms of surrender, and at 10:00 a.m. on July 4, he surrendered the city and his army to Grant. The written terms (which in the first talks were simply unconditional surrender) were negotiated so that the Confederate soldiers would be paroled and:[14]

...be allowed to march out of our lines, the officers taking with them their side-arms and clothing, and the field, staff, and cavalry officers one horse each. The rank and file will be allowed all their clothing, but no other property.[14]

Pemberton surrendered 2,166 officers and 27,230 men, 172 cannons, and almost 60,000 muskets and rifles to Grant.[14] This, combined with the successful Siege of Port Hudson on July 9, reestablished the United States complete control over the Mississippi River, a major strategic loss for the Confederacy that cut off Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith's command and the Trans-Mississippi Theater from the Confederacy for the rest of the war.

After his surrender, Pemberton was exchanged as a prisoner on October 13, 1863, and returned to Richmond. There he spent some eight months without an assignment. At first, Gen. Braxton Bragg thought he could use Pemberton. Still, after conferring with his ranking officers, he advised Davis that taking on the discredited lieutenant general "would not be advisable." Pemberton finally wrote Davis directly, asking to return to duty "in any capacity in which you think I may be useful." Davis replied that his confidence in him remained unshaken, saying:[15]

I thought and still think that you did right to risk an army for the purpose of keeping command of even a section of the Mississippi River. Had you succeeded none would have blamed; had you not made the attempt, few if any would have defended your course.[15]

Pemberton resigned as a general officer on May 9, 1864, and Davis offered him a commission as a lieutenant colonel of artillery three days later,[3] which he accepted, a testimonial of his loyalty to the Confederacy and the Confederate cause.[16] He commanded the artillery of the defenses of Richmond until January 9, 1865. He was appointed inspector general of the artillery as of January 7,[3] and held this position until he was captured in Salisbury, North Carolina, on April 12. Along with Pemberton and his 14 remaining guns, the U.S. soldiers rounded up about 1,300 men and nearly 10,000 small arms.[17] There is no record of his parole after his capture.[3]

Postbellum life

After the war, Pemberton lived on his farm near Warrenton, Virginia, from 1866 to 1876. He carried on a feud with Johnston about the Vicksburg campaign.[2] His mother, Rebecca Clifford Pemberton (1782–1869), survived her husband John Pemberton (1783–1847) by more than two decades, and a few years after her death, Pemberton returned to Pennsylvania.

Death and legacy

Pemberton died in Lower Gwynedd Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania on July 13, 1881, although his widow Martha Thompson Pemberton would survive until 1907. The families of several famous people, including General George Meade and Admiral John A. Dahlgren (whose brother also served as a Confederate General), protested against the unrepentant Confederate Pemberton's burial at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, where his mother and father had been buried. He was interred at the cemetery despite a supposed decision that the Confederate Pemberton would be interred elsewhere.[18] His sisters Rebecca Clifford Pemberton Newbold (1820–1883) and Anna Clifford Pemberton Hollingsworth (1816–1884) and brother Israel Pemberton (1813–1885, a railroad engineer) were buried at Laurel Hill shortly thereafter.

A statue depicting Pemberton, sculpted by Edmond Thomas Quinn, was erected in the Vicksburg National Military Park. His grandson, also John C. Pemberton (1893–1984),[19] in 1942 published a book about his grandfather's defense of Vicksburg, and donated family papers and his research concerning his grandfather to the University of North Carolina, which maintains them in its Special Collections.[20]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ John C. Pemberton (May 2002). Pemberton. University of North Carolina Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8078-5443-3.

- ^ a b "John C. Pemberton". www.battlefields.org. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eicher, p. 423.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Military biography of John C. Pemberton". www.library.ci.corpus-christi.tx.us. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ^ "for Gallant and Meritorious Conduct in the Battle of Molino del Rey"

- ^ Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9. p. 232.

- ^ "US National Park Service biography of Pemberton". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ^ Although this army was organized as a state establishment that was something more than a militia and which would become part of the Confederate States Army, it was not the Provisional Army of the Confederate States (PACS) and did not become part of it until after May 23, 1861, Virginia's vote to declare secession.

- ^ "Civil War Home biography of Pemberton". www.civilwarhome.com. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ a b Foote Vol. I, pp. 776–78.

- ^ a b Winters, p. 171.

- ^ "Battle of Big Black River". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 268.

- ^ a b c Foote Vol. II, pp. 606–13.

- ^ a b Foote Vol. II, p. 645.

- ^ Foote, Vol II. p. 646. "In this capacity Pemberton served out the war, often in the thick of battle, thereby demonstrating a greater devotion to the cause he had adopted than did many who had inherited it as a birthright."

- ^ Foote Vol. III, p. 967.

- ^ "John C Pemberton". www.remembermyjourney.com. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "John C. Pemberton". The New York Times. 27 October 1984.

- ^ "Collection Number: 00586. Collection Title: John C. Pemberton Papers, 1814–1942 (bulk 1922–1941)". finding-aids.lib.unc.edu.

Sources

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York, NY: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-05255-2195-2.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. 3 vols. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 978-0-394-74913-6.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- Winters, John D. The Civil War in Louisiana. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963. ISBN 978-0-8071-0834-5.

- Civil War Home biography of Pemberton

- Military biography of John C. Pemberton from the Cullum biographies

- US National Park Service biography of Pemberton

Further reading

- Ballard, Michael B. Vicksburg, The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. The Campaign for Vicksburg. 3 vols. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1985. ISBN 978-0-89029-312-6.

- Groom, Winston. Vicksburg, 1863. New York: Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26425-1.

- Winschel, Terrence J. Triumph & Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Company, 1999. ISBN 1-882810-31-7.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Jefferson Davis and His Generals: The Failure of Confederate Command in the West. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990. ISBN 0-7006-0461-8.

External links

- John C. Pemberton, National Park Service