Contents

The Northern Virginia Campaign, also known as the Second Bull Run Campaign or Second Manassas Campaign, was a series of battles fought in Virginia during August and September 1862 in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee followed up his successes of the Seven Days Battles in the Peninsula campaign by moving north toward Washington, D.C., and defeating Maj. Gen. John Pope and his Army of Virginia.

Concerned that Pope's army would combine forces with Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac and overwhelm him, Lee sent Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson north to intercept Pope's advance toward Gordonsville. The two forces initially clashed at Cedar Mountain on August 9, a Confederate victory. Lee determined that McClellan's army on the Virginia Peninsula was no longer a threat to Richmond and sent most of the rest of his army, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet's command, following Jackson. Jackson conducted a wide-ranging maneuver around Pope's right flank, seizing the large supply depot in Pope's rear, at Manassas Junction, placing his force between Pope and Washington, D.C. Moving to a very defensible position near the battleground of the 1861 First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), Jackson successfully repulsed Union assaults on August 29 as Lee and Longstreet's command arrived on the battlefield. On August 30, Pope attacked again, but was surprised to be caught between attacks by Longstreet and Jackson, and was forced to withdraw with heavy losses. The campaign concluded with another flanking maneuver by Jackson, which Pope engaged at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1.

Lee's maneuvering of the Army of Northern Virginia against Pope is considered a military masterpiece. Historian John J. Hennessy wrote that "Lee may have fought cleverer battles, but this was his greatest campaign."[4]

Background

I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies, from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary, and to beat him to when he was found; whose policy has been to attack and not defense.... Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance; disaster and shame lurk in the rear.

— John Pope, order to the "Officers and Soldiers of the Army of Virginia", July 14[5]

Military situation

After the collapse of McClellan's Peninsula campaign in the Seven Days Battles of June, President Abraham Lincoln appointed John Pope to command the newly formed Army of Virginia. Pope had achieved some success in the Western Theater, and Lincoln sought a more aggressive general than McClellan. Pope did not endear himself to his subordinate commanders—all three selected as corps commanders technically outranked him—or to his junior officers, by his boastful orders that implied Eastern soldiers were inferior to their Western counterparts. Some of his enlisted men were encouraged by Pope's aggressive tone.[6]

The Union Army of Virginia was constituted on June 26, from existing departments operating around Virginia, most of which had recently been outmaneuvered in Jackson's Valley campaign: Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont's Mountain Department, Maj. Gen Irvin McDowell's Department of the Rappahannock, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's Department of the Shenandoah, Brig. Gen. Samuel D. Sturgis's brigade from the Military District of Washington, and Brig. Gen Jacob D. Cox's division from western Virginia. The new army was divided into three corps of 51,000 men, under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel (I Corps), replacing Frémont, who refused to serve under Pope (his junior in rank) and resigned his command; Banks (II Corps); and McDowell (III Corps). Sturgis's Washington troops constituted the Army reserve. Cavalry brigades under Col. John Beardsley and Brig. Gens. John P. Hatch and George D. Bayard were attached directly to the three infantry corps, a lack of centralized control that had negative effects in the campaign. Parts of three corps (III, V, and VI) of McClellan's Army of the Potomac and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps (commanded by Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno), eventually joined Pope for combat operations, raising his strength to 77,000.[7]

On the Confederate side, General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was organized into two "wings" or "commands" (the designation of these units as "corps" would not be authorized under Confederate law until November 1862) of about 55,000 men. The "right wing" was commanded by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, the left by Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson. The Cavalry Division under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart was attached to Jackson's wing. The Confederate organization was considerably simpler than the one Lee inherited for the Seven Days Battles; in that campaign there had been eleven separate divisions, which led to breakdowns in communications and the inability of the army to execute Lee's battle plans properly. William H.C. Whiting , Theophilus Holmes, Benjamin Huger, and John B. Magruder were all reassigned elsewhere. The command structure was reorganized as follows: Jackson's wing comprised his old Valley Army; the Stonewall Division (now commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder) and Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell's division, plus the newly added command of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill. Longstreet had seven divisions. His former command was divided into two parts led by Brig. Gens. Cadmus Wilcox and James L. Kemper. Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson got Huger's division, and Brig. Gen. John B. Hood was leading Whiting's Division due to William H.C. Whiting being on sick leave. Brig. Gens. David R. Jones and Lafayette McLaws continued in command of their divisions, both of which had been part of Magruder's Army of the Peninsula. Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill's command was also placed under Longstreet. Also joining was Brig. Gen. .Nathan G. "Shanks" Evans's independent South Carolina brigade. McLaws and Hill were left in Richmond under the command of Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith, and so Longstreet would take only five divisions north.[8]

Plans

Pope's mission was to fulfill a few objectives: protect Washington and the Shenandoah Valley, and draw Confederate forces away from McClellan by moving in the direction of Gordonsville.[9] Pope started on the latter by dispatching cavalry to break the Virginia Central Railroad connecting Gordonsville, Charlottesville, and Lynchburg. The cavalry under Hatch got off to a slow start and found that Stonewall Jackson had already occupied Gordonsville on July 19 with over 14,000 men. (After a subsequent second failure to cut the railroad on July 22, Pope removed Hatch from his cavalry command and reassigned him to command an infantry brigade in Brig. Gen. Rufus King's division of the III Corps.)[10]

Pope had an additional, broader objective, encouraged by Abraham Lincoln. For the first time, the Union intended to pressure the civilian population of the Confederacy by bringing some of the hardships of war directly to them. Pope issued three general orders on the subject to his army. General Order No. 5 directed the army to "subsist upon the country," reimbursing farmers with vouchers that were payable after the war only to "loyal citizens of the United States." To some soldiers, this became an informal license to pillage and steal. General Orders 7 and 11 dealt with persistent problems of Confederate guerrillas operating in the Union rear. Pope ordered that any house from which gunfire was aimed at Union troops be burned and the occupants treated as prisoners of war. Union officers were directed to "arrest all disloyal male citizens within their lines or within their reach." These orders were substantially different from the war philosophy of Pope's colleague McClellan, which undoubtedly caused some of the animosity between the two men during the campaign. Confederate authorities were outraged and Robert E. Lee labeled Pope a "miscreant" and added that he "ought to be suppressed."[11]

Based on his experiences in the Seven Days, Lee concluded that McClellan would not attack, and he could thus move most of his army away from Richmond. This allowed him to relocate Jackson to Gordonsville to block Pope and protect the Virginia Central. Lee had larger plans in mind. Since the Union Army was split between McClellan and Pope and they were widely separated, Lee saw an opportunity to destroy Pope before returning his attention to McClellan.[12]

Initial movements

On July 26, Lee met with cavalry commander and partisan fighter Capt. John S. Mosby, who had just been exchanged as a prisoner of war. Coming through the Hampton Roads area in Union custody, Mosby observed significant naval transport activity and deduced that Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's troops, who had fought in North Carolina, were being shipped to reinforce Pope. Wanting to take immediate action before those troops were in position, the next day Lee committed Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to join Jackson with 12,000 men, while distracting McClellan with artillery bombardments and diversionary movements. McClellan advanced a force from Harrison's Landing to Malvern Hill, and Lee moved south to meet the threat, but McClellan eventually withdrew his advance. Still convinced that he was heavily outnumbered, he sent messages to Washington that he would need at least 50,000 more men before he could attempt another attack on Richmond. On August 3, General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck directed McClellan to begin his final withdrawal from the Peninsula and to return to Northern Virginia to support Pope. McClellan protested and did not begin his redeployment until August 14. The Army of the Potomac returned to Washington except for a division of the IV Corps, which was left on the Virginia Peninsula.[13]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battles and movements

On July 29, Pope moved his headquarters from Washington to the field. He was informed by Halleck of the plan to link up with McClellan's army, but rather than waiting for this to occur, he moved some of his forces to a position near Cedar Mountain, from whence he could launch cavalry raids on Gordonsville. Jackson advanced to Culpeper Court House on August 7, hoping to attack one of Pope's corps before the rest of the army could be concentrated.[14]

Cedar Mountain

On August 9, Nathaniel Banks's corps attacked Jackson at Cedar Mountain, gaining an early advantage. Confederate Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder was killed and his division mauled. A Confederate counterattack led by Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill drove Banks back across Cedar Creek. Jackson's advance was stopped, however, by the Union division of Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts. By now Jackson had learned that Pope's corps were all together, foiling his plan of defeating each in separate actions. He remained in position until August 12, then withdrew to Gordonsville.[15]

Lee advances to the Rappahannock

On August 13, Lee sent Longstreet to reinforce Jackson, and on the following day Lee sent all of his remaining forces (except for two brigades) after he was certain that McClellan was leaving the Peninsula. Lee arrived at Gordonsville to take command on August 15. He massed the Army of Northern Virginia south of Clark's Mountain and planned a turning movement to defeat Pope before McClellan's army could arrive to reinforce it. His plan was to send his cavalry under Stuart, followed by his entire army, north to the Rapidan River on August 18, screened from view by Clark's Mountain. Stuart would cross and destroy the railroad bridge at Somerville Ford and then move around Pope's left flank into the Federal rear, destroying supplies and blocking their possible avenues of retreat. Logistical difficulties and cavalry movement delays caused the plan to be abandoned.[16]

On August 20–21, Pope withdrew to the line of the Rappahannock River. He was aware of Lee's plan because a Union cavalry raid captured a copy of the written order. Stuart was almost captured during this raid; his cloak and plumed hat did not escape, however, and Stuart retaliated on August 22 with a raid on Pope's headquarters at Catlett's Station, capturing the Union commander's dress coat. Stuart's raid demonstrated that the Union right flank was vulnerable to a turning movement, although river flooding brought on by heavy rains would make this difficult. It also revealed the plans for reinforcing Pope's army, which would eventually bring it to the strength of 130,000 men, more than twice the size of the Army of Northern Virginia.[17]

Skirmishing on the Rappahannock

The two armies fought a series of minor actions August 22–25 along the Rappahannock River, including Waterloo Bridge, Lee Springs, Freeman's Ford, and Sulphur Springs, resulting in a few hundred casualties.[18] Together, these skirmishes kept the attention of both armies along the river. Heavy rains had swollen the river and Lee was unable to force a crossing. Pope considered an attack across the river to strike Lee's right flank, but he was also stymied by the high water. By this time, reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac were arriving from the Peninsula: Maj. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman's III Corps, Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter's V Corps, and elements of the VI Corps under Brig. Gen. George W. Taylor. Lee's new plan in the face of all these additional forces outnumbering him was to send Jackson and Stuart with half of the army on a flanking march to cut Pope's line of communication, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. The Hotchkiss journal shows that Jackson, most likely, originally conceived the movement. In the journal entries for March 4 and 6 1863, General Stuart tells Hotchkiss that "Jackson was entitled to all the credit" for the movement and that Lee thought the proposed movement "very hazardous" and "reluctantly consented" to the movement.[19][20] Pope would be forced to retreat and could be defeated while moving and vulnerable. Jackson departed on August 25 and reached Salem (present-day Marshall) that night.[21]

Raiding Manassas Station

On the evening of August 26, after passing around Pope's right flank via Thoroughfare Gap, Jackson's wing of the army struck the Orange & Alexandria Railroad at Bristoe Station and before daybreak August 27 marched to capture and destroy the massive Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. This surprise movement forced Pope into an abrupt retreat from his defensive line along the Rappahannock. On August 27, Jackson routed the New Jersey Brigade of the VI Corps near Bull Run Bridge, mortally wounding its commander George W. Taylor. Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's Confederate division fought a brisk rearguard action against Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's division at Kettle Run, resulting in about 600 casualties. Ewell held back Union forces until dark. During the night of August 27 – August 28, Jackson marched his divisions north to the First Bull Run (Manassas) battlefield, where he took position behind an unfinished railroad grade.[22] Pope did not know where Jackson had gone.

Thoroughfare Gap

After skirmishing near Chapman's Mill in Thoroughfare Gap, Ricketts's Union division was flanked on August 28 by a Confederate column passing through Hopewell Gap several miles to the north and by troops securing the high ground at Thoroughfare Gap. Ricketts retired, and Longstreet's wing of the army marched through the gap to join Jackson. This seemingly inconsequential action virtually ensured Pope's defeat during the battles of August 29–30 because it allowed the two wings of Lee's army to unite on the Manassas battlefield. Ricketts withdrew via Gainesville to Manassas Junction.[23]

Second Bull Run (Manassas)

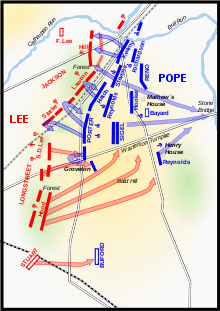

The most significant battle of the campaign, Second Bull Run (Second Manassas), was fought August 28–30.[24] In order to draw Pope's army into battle, Jackson ordered an attack on a Federal column that was passing across his front on the Warrenton Turnpike on August 28, alerting Pope to his position. The fighting at Brawner's Farm lasted several hours and resulted in a stalemate.

Pope became convinced that he had trapped Jackson and concentrated the bulk of his army against him. On August 29, Pope launched a series of assaults against Jackson's position along the unfinished railroad grade. The attacks were repulsed with heavy casualties on both sides. At noon, Longstreet arrived on the field from Thoroughfare Gap and took position on Jackson's right flank.

On August 30, Pope renewed his attacks, seemingly unaware that Longstreet was on the field. When massed Confederate artillery devastated a Union assault by Porter's corps, Longstreet's wing of 28,000 men counterattacked in the largest simultaneous mass assault of the war. The Union left flank was crushed and the army driven back to Bull Run. Only an effective Union rearguard action prevented a replay of the First Bull Run disaster. Pope's retreat to Centreville was precipitous, nonetheless. The next day, Lee ordered his army to pursue the retreating Union army.[25]

Chantilly

Making a wide flanking march, Jackson hoped to cut off the Union retreat from Bull Run. On September 1, beyond Chantilly Plantation on the Little River Turnpike near Ox Hill, Jackson sent his divisions against two Union divisions under Maj. Gens. Philip Kearny and Isaac Stevens. Confederate attacks were stopped by fierce fighting during a severe thunderstorm. Union generals Stevens and Kearny were both killed. Recognizing that his army was still in danger at Fairfax Courthouse, Pope ordered the retreat to continue to Washington.[26]

Aftermath

The northern Virginia campaign had been expensive for both sides, although Lee's smaller army spent its resources more carefully. Union casualties were 16,054 (1,724 killed, 8,372 wounded, 5,958 missing/captured) out of about 75,000 engaged, roughly comparable to the losses two months earlier in the Seven Days Battles; Confederate losses were 9,197 (1,481 killed, 7,627 wounded, 89 missing/captured) of 48,500.[1]

Edward Porter Alexander wrote:

- The [Army of Northern Virginia] acquired that magnificent morale which made them equal to twice their numbers, & which they never lost even to the surrender at Appomattox. And [Lee's] confidence in them, & theirs in him, were so equal that no man can yet say which was greatest[27]

The campaign was a triumph for Lee and his two principal subordinates. Military historian John J. Hennessy described it as Lee's greatest campaign, the "happiest marriage of strategy and tactics he would ever attain." He balanced audacious actions with proper caution and chose his subordinates' roles to best effect. Jackson's flank march—54 miles in 36 hours into the rear of the Union Army—was "the boldest maneuver of its kind during the war, and Jackson executed it flawlessly." Longstreet's attack on August 30, "timely, powerful, and swift, would come as close to destroying a Union army as any ever would."[28]

Pope, outmaneuvered by Lee, was virtually besieged in Washington. If it were not for his close political and personal ties to President Lincoln, his military career might have been completely ruined. Instead, he was transferred to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and command of the Army's Department of the Northwest, where he fought the Dakota War of 1862.[29] Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan assumed command of all Union forces around Washington, and his Army of the Potomac absorbed the forces of the Army of Virginia, which was disbanded on September 12, 1862.

With Pope no longer a threat and McClellan reorganizing his command, Lee turned his army north on September 4 to cross the Potomac River and invade Maryland, initiating the Maryland campaign and the battles of Harpers Ferry, South Mountain, and Antietam.[30]

The Bull Run battlefields are preserved by the National Park Service in Manassas National Battlefield Park.

Notes/References

- ^ a b c d Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 334.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 12/1, pp. 139, 262.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), pp. 334–335

16,054 (1,724 killed; 8,372 wounded; 5,958 missing/captured) according to Eicher. - ^ Hennessy (1992), p. 458.

- ^ Hennessy (1992), p. 12.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 318; Hennessy (1992), p. 12; Martin (1996), p. 24, 32-33.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 318; Hennessy (1992), p. 6; Martin (1996), p. 280.

- ^ Freeman (1946), p. 610-614; Glatthaar (2008), p. 157-158; Harsh (1998), p. 106; Hennessy (1992), p. 561-567; Langellier (2002), p. 90-93.

- ^ Esposito (1959), p. 54

Esposito's Map 54 - ^ Esposito (1959), p. 55; Martin (1996), p. 45-46

Esposito's Map 55 - ^ Hennessy (1992), p. 14-21; Martin (1996), p. 36-37.

- ^ Harsh (1998), p. 119-123.

- ^ Esposito (1959), p. 56; Hennessy (1992), p. 157-158; Sears (1992), p. 106; Welcher (1989), p. 835-36

Esposito's Map 56 - ^ Esposito (1959), p. 56

Map 56 - ^ NPS Cedar Mountain.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 322; Esposito (1959), p. 57; Hennessy (1992), p. 35-51

Esposito's Map 57 - ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 322; Esposito (1959), p. 57; Martin (1996), p. 92, 101-02

Esposito's Map 57 - ^ NPS First Rappahannock Station (White Sulphur Springs).

- ^ Collie. MilitaryHistoryOnline.com, 2017.

- ^ Hotchkiss (1973), p. 117-118; Robertson (1997), p. 547, 887.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 322-323; Esposito (1959), p. 58; Salmon (2001), p. 127-128

Esposito's Map 58 - ^ NPS Manassas Station Operations.

- ^ NPS Thoroughfare Gap.

- ^ NPS Second Bull Run,

The NPS has established these dates for the battle. The references by Greene, Hennessy, Salmon, and Kennedy, whose works are closely aligned with the NPS, adopt these dates as well. However, all of the other references to this article specify that the action on August 28 was a prelude to, but separate from, the Second Battle of Bull Run. Some of these authors name the action on August 28 the Battle of Groveton or Brawner's Farm. - ^ NPS Second Bull Run.

- ^ NPS Battle of Chantilly.

- ^ Alexander (1989), p. 139.

- ^ Hennessy (1992), p. 457-61.

- ^ Martin (1996), p. 33.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 336-37.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Edward P. (1989). Gary W. Gallagher (ed.). Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (1st (September 22, 1989) ed.). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 692. ISBN 9780807818480. OCLC 1053980665.

- Eicher, David J.; McPherson, James M.; McPherson, James Alan (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1846-9. OCLC 892938160.

- Esposito, Vincent J. (1959). West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York City: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8050-3391-5. OCLC 60298522.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall (1946). Manassas to Malvern Hill (PDF). Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. Vol. I (1970 Scribner ed.). New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 773. ISBN 9780684187488. OCLC 1035890441.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. (2008). General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse (1st edition (March 18, 2008) ed.). New York, NY: Free Press. p. 624. ISBN 9780684827872. OCLC 144767946.

- Harsh, Joseph L. (1998). Confederate Tide Rising: Robert E. Lee and the Making of Southern Strategy, 1861–1862 (Reprint edition (March 19, 2019) ed.). Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. p. 278. ISBN 9781606353844. OCLC 1089908147.

- Hennessy, John J. (1992). Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas (First Edition (November 1, 1992) ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 448. ISBN 9780671793685. OCLC 26095816.

- Hotchkiss, Jedediah (1973). MacDonald, Archie P. (ed.). Make Me a Map of the Valley: The Civil War Journal of Stonewall Jackson's Topographer (PDF) (3rd (1988) ed.). Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press. p. 410. ISBN 9780870741371. OCLC 562307122. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Langellier, John (2002). Second Manassas 1862: Robert E. Lee's Greatest Victory. Osprey Campaign (1st edition (February 25, 2002) ed.). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 9781841762302. OCLC 843344073.

- Martin, David George (1996). The Second Bull Run Campaign: July–August 1862. Great Campaigns (1st ed. (November 21, 1996) ed.). New York, NY: Da Capo Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780938289807. OCLC 35198720.

- Robertson, James I. Jr. (1997). Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend (PDF). London, UK: Prentice Hall International. p. 950. ISBN 978-0-02-864685-5. OCLC 1151321680. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811728684.

- Sears, Stephen W. (1992). To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (Hardcover) (1st ed. (September 1, 1992) ed.). Boston, MA: Stan Clark Military Books (Houghton Mifflin Co.). p. 468. ISBN 0899197906. OCLC 34006957.

- U.S. War Department (1885). Reports, Mar 17 – Jun 25; Operations in Northern Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. Mar 17 – Sep 2, 1862. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. XII-XXIV-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924077725921. OCLC 427057.

- Welcher, Frank J. (1989). The Eastern Theater. The Union Army, 1861-1865: Organization and Operations. Vol. 1 (1st, (October 1, 1989) ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 1084. ISBN 9780253364531. OCLC 799063447.

- Collie, Michael (2017). "Origin of the Movement Around Pope's Army of Virginia, August 1862". militaryhistoryonline.com. MilitaryHistoryOnline.com, LLC. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Cedar Mountain". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012.

- "Chantilly". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012.

- "Manassas, Second". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2005. Archived from the original on November 26, 2005.

- "Manassas Station Operations". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012.

- "Rappahannock Station". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012.

- "Thoroughfare Gap". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012.

Further reading

- Anthony, Nicholas J. (1984). Lee Takes Command: From Seven Days to Second Bull Run. The Civil War (1st edition (January 1, 1984) ed.). Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books. ISBN 9780809448043. OCLC 733726003.

- Dyer, Frederick H (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (PDF). Des Moines, IA: Dyer Pub. Co. ASIN B01BUFJ76Q. OCLC 8697590.

- Greene, A. Wilson (1995). The Second Battle of Manassas. National Park Service Civil War Series (1st edition (January 1, 1995) ed.). Fort Washington, PA: Eastern National Park and Monument Association. p. 55. ISBN 091599285X. OCLC 33147466.

- Hattaway, Herman; Jones, Archer (1983). How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 762. ISBN 9780252062100. OCLC 924976443.

- Henderson, George Francis Robert (1898). Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War (PDF). Vol. I (1st ed.). London UK: Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 648. OCLC 1085324715.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0395740126.

- Sauers, Richard Allen (2000). David Stephen Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler; James M. McPherson (Introduction) (eds.). Second Battle of Bull Run. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (Reissue edition (September 16, 2002) ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 2733. ISBN 9780393047585. OCLC 1001976604.

- Stackpole, Edward J. (1959). From Cedar Mountain to Antietam (Hardcover) (1st edition (January 1, 1959) ed.). Harrisburg, PA: The Stackpole Company. p. 466. ISBN 9780811724388. OCLC 814411747.

- Whitehorne, Joseph W. A. (1990). The Battle of Second Manassas: Self-Guided Tour. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. p. 70. OCLC 644264587. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2010-08-04.

- Wood, William J. (1997). Civil War Generalship: The Art of Command (PDF) (Praeger Illustrated edition (April 9, 1997) ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 288. ISBN 9780275950545. OCLC 1193365637.

- Woodworth, Steven E.; Winkle, Kenneth J.; McPherson, James M. (foreword) (2004). Oxford Atlas of the Civil War. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 9780195221312. OCLC 1136147162.