Contents

9°26′6.33″S 159°57′4.46″E / 9.4350917°S 159.9512389°E

The British Solomon Islands Protectorate was first declared over the southern Solomon Islands in June 1893, when Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa, declared the southern islands a British protectorate.[1][2]

Christian missionaries began visiting the Solomons from the 1840s, beginning with an attempt by French Catholics under Jean-Baptiste Epalle to establish a mission on Santa Isabel Island, which was abandoned after Epalle was killed by islanders in 1845.[3][4] Anglican missionaries began arriving from the 1850s, followed by other denominations, over time gaining a large number of converts.[5]

The Anglo-German Declarations about the Western Pacific Ocean (1886), established "spheres of influence" that Imperial Germany and the United Kingdom agreed, with Germany giving up its claim to the southern Solomon Islands. Following the formal declaration of the Protectorate in 1893, Bellona and Rennell Islands and Sikaiana (formerly the Stewart Islands) were added to the Protectorate in 1897, and the Santa Cruz group, the Reef Islands, Anuda (Cherry), Fataka (Mitre) and Trevannion Islands and Duff (Wilson) group in 1898. German interests in the islands to the east and south-east of Bougainville were transferred to the United Kingdom under the Samoa Tripartite Convention of 1899, in exchange for recognition of the German claim to Western Samoa. In October 1900, the High Commissioner issued a Proclamation extending the Protectorate to the islands in question, i.e. Choiseul, Ysabel, Shortland and Fauro Islands (each with its dependencies), the Tasman group, Lord Howe's group and Gower Island.[6][2]

The Protectorate was administered as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT) until the Solomon Islands became independent in 1978. During the 1950s, the British colonial administration built a network of official local councils. On this platform Solomon Islanders with experience on the local councils started participation in central government, initially through the bureaucracy and then, from 1960, through the newly established Legislative and Executive Councils. The 1970 constitution replaced the Legislative and Executive Councils with a single Governing Council.

A new constitution was introduced in 1974 which established a standard Westminster form of government and gave the Islanders both Chief Ministerial and Cabinet responsibilities. Governing Council was transformed into the Legislative Assembly. The Protectorate that existed over Solomon Islands was ended under the terms of the Solomon Islands Act 1978.

Establishment and addition of islands

After the Anglo-German Declarations about the Western Pacific Ocean (1886), the Protectorate was first declared over the southern Solomons in June 1893.[2] The formalities in its establishment were carried out by Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa, who hoisted the British flag and read Proclamations on twenty-one islands.[2]

In April 1896, Charles Morris Woodford was appointed as an Acting Deputy Commissioner of the British Western Pacific Territories. From 30 May to 10 August 1896, HMS Pylades toured through the Solomon Islands archipelago with Woodford, who had been sent to survey the islands and to report on the economic feasibility of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate.[6] On 29 September 1896, in anticipation of the establishment of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, Woodford purchased the island of Tulagi, which he selected as the site for the administrative centre.[6] The Colonial Office appointed Woodford as the Resident Commissioner in the Solomon Islands on 17 February 1897. He was directed to control the labour trade operating in the Solomon Island waters and to stop the illegal trade in firearms.[6]

Bellona and Rennell Islands and Sikaiana (formerly the Stewart Islands) were added to the Protectorate in 1897, and the Santa Cruz group, the Reef Islands, Anuda (Cherry), Fataka (Mitre) and Trevannion Islands and Duff (Wilson) group in 1898.[6][2] On 18 August 1898 and 1 October 1898, the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific issued Proclamations which declared (apparently superfluously) that all those islands should "henceforth" form part of the Protectorate.[2] The two Proclamations of 1898 were superseded by one dated 28 January 1899, which was apparently intended not to consolidate them but also to correct geographical errors: it lists "the Reef Islands, Swallow Group" and a different group of islands referred to collectively as "the Swallow Group," and it includes Trevannion in the Santa Cruz group.[2]

German interests in the islands to the east and south-east of Bougainville were transferred to the United Kingdom under the Samoa Tripartite Convention of 1899, in exchange for recognition of the German claim to Western Samoa.[7][8][9][10][11] In October 1900, the High Commissioner issued a Proclamation extending the Protectorate to the islands in question, i.e. Choiseul, Ysabel, Shortland and Fauro Islands (each with its dependencies), the Tasman group, Lord Howe's group and Gower Island.[2][6]

Suppression of headhunting and punitive expeditions

From the establishment of British colonial rule until approximately 1902, Solomon Islanders continued to launch headhunting raids and murder European traders and colonists. The British responded by dispatching Royal Navy warships to launch punitive expeditions against the villages responsible in an effort to curb such activities.[6][12][13]

On September 1891, several Kalikoqu tribesmen killed a European trader operating on Uki Island named Fred Howard. In response, the screw-sloop HMS Royalist launched a punitive expedition against the village responsible, killing several of the tribesmen who were involved in the murder along with burning the village and destroying several of its canoes.[14]

In March 1897, the Royal Navy warship HMS Rapid launched a punitive expedition, targeting villages which had been responsible for the murders of European traders and colonists on the islands of Rendova, New Georgia, Nggatokae and Vella Lavella.[15]

Arthur Mahaffy was appointed as the Deputy Commissioner in January 1898.[6][16] In January 1900, Mahaffy established a government station at Gizo, as Woodford considered Mahaffy’s military training as making him suitable for the role of suppressing headhunting in New Georgia and neighbouring islands.[6][17] Mahaffy had a force of twenty-five police officers armed with rifles.[16] The first target of this force was chief Ingava of the Roviana Lagoon of New Georgia who had been raiding Choiseul and Isabel and killing or enslaves hundreds of people.[16]

Mahaffy and the police officers under his command carried out a violent and ruthless suppression of headhunting, with his actions having the support of Woodford and the Western Pacific High Commission, who wanted to eradicate headhunting and complete a “pacification” of the western Solomon Islands.[6] Mahaffy seized and destroyed large war canoes (tomokos). One of which was used to transport the police officers.[16] The western Solomon were substantially pacified by 1902.[6] During this time Mahaffy acquired artefacts held in high value by the Solomon Islanders for his personal collection.[18]

Arthur Mahaffy visited Malaita on HMS Sparrow (1889), as a resident magistrate, in 1902 to investigate several deaths. Mahaffy demanded the Malaitians give up the person believed to be the murderer, and when they did not, Sparrow shelled the village and a shore party burnt down the village and killed the pigs.[19] Malaita was a difficult island to administer as Mahaffy believed that 80 per cent of Malaitan males possessed firearms in the 1900s. There were frequent inter-tribal killings and pay-back killings. Indiscriminate naval bombardments or naval shore parties destroying villages, canoes and killing pigs to punish Solomon Islanders was a common response to incidents, where the colonial administrators could not arrest the perpetrators of killings.[19]

Shipping in the Solomon Islands

Woodford initially used a 27-foot open whaleboat to travel between the islands,[15] or travelled on any available trading boat or Royal Navy ship. From 1896 the Burns Philp steamship the Titus was making between four and seven voyages from Sydney to the Solomon Islands. Two ships owned by Gustavus John Waterhouse of Sydney operated in the Solomon Islands; the schooner Chittoor, and SS Kurrara, a steam ship. The schooner Lark owned by J. Hawkins, from Sydney, also sailed in the waters of the Solomon Islands.[20]

In 1899, Woodford purchased the Lahloo, a 33-ton ketch, which he used for suppressing head-hunting in the New Georgia group. The Lahloo was wrecked in 1909. The Belama, a 100-ton steam ship, was acquired in 1909. However, it was wrecked in February 1911 when it struck an uncharted reef off Isabel. The replacement ship, also named Belama, (previously the river steamer Awittaka) arrived at Tulagi in August 1911. It was wrecked off Isabel in 1921.[21]

From about 1900, Burns Philp had a dominant role in trade in the region distributing general merchandise and collecting copra.[21] Ships servicing the Levers Pacific Plantations started in 1903. In 1904, Burns Philp began to acquire plantations and land to develop into plantations in the British Solomon Islands.[21]

W. R. Carpenter & Co. (Solomon Islands) Ltd was established in 1922 and became storekeepers, traders, and operated a fleet of inter-island steamers.[22][23]

Plantation economy

The policy of the colonial officials was to attempt to make the protectorate self-supporting through taxes imposed on copra and other products exported from the Islands. The long-term interests of the islanders was relegated to a secondary priority as the colonial officials focused on encouraging investment by British and Australian corporate trading companies and individual plantation owners. By 1902, there were about 83 Europeans in the Solomon Islands, with most engaged in the development of copra plantations.[24]

The Solomon (Waste Land) Regulation of 1900 (Queen's Regulation no. 3 of 1900), and later revisions, was intended by the British Solomon Islands administration in Tulagi, the Western Pacific High Commission in Suva, and the Colonial Office in London to make land available for commercial plantations by a formal process of identifying ‘waste land' – that is land not occupied by Solomon Islanders – which could be declared “not owned, cultivated, or occupied by any native or non-native person”.[24] Regulation 3 of 1900 implemented a concept of ‘waste land' that was not consistent with Melanesian customs, as unoccupied land was still recognised by customary law as being the property of individual people and communities.[24]

From 1900 to 1902, an attempt was made by the Pacific Islands Company Ltd to establish plantations. However, it was unable to raise sufficient capital to establish plantations because Regulation 3 of 1900 only permitted the issue of ‘Certificates of Occupation’ of the land and not a formal lease. This limited right to occupy the land were not accepted by financiers as sufficient collateral to finance development of plantations.[25]

In 1903, Levers Pacific Plantations Limited purchased 50,000 acres of coconut plantations from Lars Nielsen for £6,500, and in 1906 the company purchased the coconut plantation concessions from the Pacific Islands Company Ltd for £5,000. By 1905 the company had acquired approximately 80,000 acres in the Solomon Islands which were distributed over 14 islands: 51,000 acres from Lars Nielsen and other plantation owners, and 28,870 acres purchased from islanders.[26]

The plantation companies came into conflict with Charles Morris Woodford, the Resident Commissioner in the Solomon Islands, over his management of land alienation from the Solomon Islanders to plantation owners. The complaints including Woodford withdrawing ‘waste land’ from transfer to plantation owners when the original Solomon Islander owners were identified, and insisting on strict conformity with the improvement clauses on leases.[27] The Solomons (Land) Regulation of 1914 (King's Regulation no. 3 of 1914), replace earlier regulations, and ended the alienation of land from Solomon Islander owners and a leasehold system was instituted for plantation land.[27]

Levers Pacific Plantations Ltd, a subsidiary of Lever Brothers, became the largest operator of plantations, with 26 plantations established by 1916. The Malayta Company operated 7 plantations, and was controlled by the Young family who were associated with the South Seas Evangelical Church. Burns, Philp & Co operated 7 plantations through subsidiaries - the Solomon Islands Development Company, the Shortland Islands Plantation Ltd and Choiseul Plantations Ltd.[28] Burns Philp acquired 800 acres of coconut plantations in the Shortland Islands and other properties from plantation owners.[28] In 1917, Burns Philp acquired 15,000 acres of grass lands on Guadalcanal on a 999 year lease.[28]

These corporate plantation owners employed 55 per cent of the Solomon Islanders engaged in the copra industry, with individual plantation owners employing the remaining 45 per cent.[29]

Burns, Philp acquired the island of Makambo in Tulagi Harbour to operate as a trading station and cargo depot in competition with Lever’s operation on Gavutu Island that was nearby Tulagi.[30] Tulagi contained the administrative headquarters of the Protectorate and other facilities such as the hospital and jail, as well as a hotel and clubhouse for administrators and plantation owners.[30]

World War II

Japanese invasion of the Solomon Islands

In 1940 Donald Gilbert Kennedy joined the administration of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Kennedy organised an intelligence-gathering network of local informants and messengers to carry out the role of Coastwatchers to monitor Japanese activity. The Coastwatchers were planters, government officials, missionaries and islanders monitoring who went into hiding after the Japanese invasion of the Solomon Islands in January 1942. The Coastwatchers monitored Japanese shipping and aircraft (reporting by radio) and also rescued Allied personnel who were stranded in the territory held by the Japanese.[31][32][33]

The counter-attack was led by the United States; the 1st Division of the US Marine Corps landed on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in August 1942. Some of the bitterest fighting of World War II took place on the islands for almost three years.

Tulagi, the seat of the British administration on the island of Nggela Sule in Central Province was destroyed in the heavy fighting following landings by the US Marines. Then the tough battle for Guadalcanal, which was centered on the capture of the airfield, Henderson Field, led to the development of the adjacent town of Honiara as the United States logistics center.

Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana

Islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana were Allied scouts during the war. They became famous when they were noted by National Geographic for being the first men to find the shipwrecked John F. Kennedy and his crew of the PT-109 using a traditional dugout canoe. They suggested the idea of using a coconut to write a rescue message for delivery. The coconut was later kept on Kennedy's desk. Their names had not been credited in most movie and historical accounts, and they were turned back before they could visit President Kennedy's inauguration, though the Australian coastwatcher would also meet the president.

Gasa and Kumana were interviewed by National Geographic in 2002, and can be seen on the DVD of the television special. They were presented a bust by Max Kennedy, a son of Robert F. Kennedy. The National Geographic had gone there as part of an expedition by Robert Ballard, who found the remains of the PT-109. The special was called The Search for Kennedy's PT 109.[34]

Ambassador Caroline Kennedy met John Koloni, the son of Kumana, and Nelma Ane, daughter of Gasa at a ceremony in August 2023 in Honiara to mark the 80th anniversary of the battle of Guadalcanal. She also visited the places that her father had swum after the sinking of PT 109.[35][36][37]

War consequences

The impact of the war on islanders was profound. The destruction caused by the fighting and the longer-term consequences of the introduction of modern materials, machinery and western cultural artifacts, transformed traditional isolated island ways of life. The reconstruction was slow in the absence of war reparations and with the destruction of the pre-war plantations, formerly the mainstay of the economy. Significantly, the Solomon Islanders' experience as labourers with the Allies led some to a new appreciation of the importance of economic organisation and trade as the basis for material advancement. Some of these ideas were put into practice in the early post-war political movement "Maasina Ruru"—often redacted to "Marching Rule".

Towards independence

Legislative Council and Executive Council

Stability was restored during the 1950s, as the British colonial administration built a network of official local councils. On this platform Solomon Islanders with experience on the local councils started participation in central government, initially through the bureaucracy and then, from 1960, through the newly established Legislative and Executive Councils. The Protectorate did not possess a constitution of its own until 1960.[2] Positions on both Councils were initially appointed by the High Commissioner for the Western Pacific,[2] but progressively more of the positions were directly elected or appointed by electoral colleges formed by the local councils.

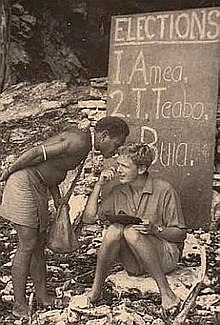

A major issue faced by the authorities in extending democratic representation was the low level of literacy, estimated to be below 6% in 1970.[38] The solution was to allow for voters to whisper their vote to the presiding official, normally the District commissioner or District officer who recorded the votes cast this way.[39][40]

Proposed transfer to Australia

In the 1950s, British and Australian government officials contemplated transferring sovereignty of the Solomon Islands from the United Kingdom to Australia. The Solomon Islands had close ties to Australia; it used the Australian pound, relied on Australian air and shipping services, employed many Australians as civil servants, and its businesses were dependent upon Australian capital. Some Australian officials argued that the British had shown little interest in the development of the islands, while British officials believed Australia did not have sufficient trained staff to take over the administration. Unlike Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and the New Hebrides, Australia made no formal request for a transfer of sovereignty. However, there were informal discussions between officials in the Colonial Office and the Australian Department of Territories.[41][42]

In 1956, Australian territories minister Paul Hasluck proposed to federal cabinet that Australia take over the Solomons, with the support of External Affairs Minister Richard Casey. It was proposed that Australia would effectively double the annual development funds that the UK had allocated to the Solomons, from £1,073,533 (equivalent to £29,000,000 in 2021) to about £2,000,000 (equivalent to £53,000,000 in 2021). However, Australia's Treasury Department was unenthused about the additional expenditure, and the Department of Defence stated there was "no defence advantage in assuming responsibility" with the islands in British hands. The Australian cabinet rejected the proposal.[41][42]

First national election

The first national election was held in 1964 for the seat of Honiara, and by 1967 the first general election was held for all but one of the 15 representative seats on the Legislative Council (the one exception was the Eastern Outer Islands constituency, which was again appointed by electoral college).

Elections were held again in 1970 and a new constitution was introduced. The 1970 constitution replaced the Legislative and Executive Councils with a single Governing Council. It also established a 'committee system of government' where all members of the Council sat on one or more of five committees. The aims of this system were to reduce divisions between elected representatives and the colonial bureaucracy and to provide opportunities for training new representatives in managing the responsibilities of government. It was also claimed that this system was more consistent with the Melanesian style of government, however, this was quickly undermined by opposition to the 1970 constitution and the committee system by elected members of the council. As a result, a new constitution was introduced in 1974 which established a standard Westminster form of government and gave the Islanders both Chief Ministerial and Cabinet responsibilities. Solomon Mamaloni became the country's first Chief Minister in July 1974 and the Governing Council was transformed into the Legislative Assembly. The protectorate that existed over Solomon Islands was ended under the terms of the Solomon Islands Act 1978 which annexed the territories comprising the protectorate as part of Her Majesty’s dominions.

Notes

- ^ as Resident Commissioner

References

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 6 The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Commonwealth and Colonial Law by Kenneth Roberts-Wray, London, Stevens, 1966. P. 897

- ^ "Exploration". Solomon Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Issue on the Solomon Islands" (PDF). UN Department of Political Affairs. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "Religion". Solomon Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 7 Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 198–206. doi:10.22459/NBI.10.2014. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ "Solomon IslandsArticle Free Pass". britannica.com. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "Solomon Islands". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "British Solomon Islands Protectorate c.1906–1947 (Solomon Islands)". crwflags.com. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "UK and Solomon Islands". gov.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Relations With the Solomon Islands". state.gov. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 6 The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 195–196. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 8 The new social order" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 220–225. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Nolden, Sascha (29 March 2016). "Surveying in the South Pacific". National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ a b Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 6 The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b c d "Mahaffy, Arthur (1869 - 1919)". Solomon Islands Historical Encyclopaedia 1893-1978. 2003. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Coates, Austin (1970). Western Pacific Islands. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 229. ISBN 978-0118804288.

- ^ Aoife O'Brien (2017). "Crime and Retribution in the Western Solomon Islands: Punitive raids, material culture, and the Arthur Mahaffy collection, 1898–1904". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 18 (1). doi:10.1353/cch.2017.0000.

- ^ a b Moore, Clive (October 2014). Making Mala - Malaita in Solomon Islands, 1870s–1930s. ANU Press. p. 311-312. ISBN 9781760460976.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 6 The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. p. 177. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 282–283. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ WR Carpenter (PNG) Group of Companies: About Us, http://www.carpenters.com.pg/wrc/aboutus.html Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12 December 2011.

- ^ Deryck Scarr: Fiji, A Short History, George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, Herts, England, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 245–249. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 249–256. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 255 & 266-69. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 266–69. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b c Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 270–281. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 10 The critical question of labour" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ a b Lawrence, David Russell (October 2014). "Chapter 9 The plantation economy" (PDF). The Naturalist and his "Beautiful Islands": Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific. ANU Press. p. 271. ISBN 9781925022032.

- ^ Laracy, Hugh (2013). "Chapter 11 - Donald Gilbert Kennedy (1897-1967) An outsider in the Colonial Service" (PDF). Watriama and Co: Further Pacific Islands Portraits. Australian National University Press. ISBN 9781921666322.

- ^ "Coastwatchers". Solomon Islands Historical Encyclopaedia 1893–1978. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Coastwatcher Donald Kennedy". Axis History Forum. 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "JFK's PT-109 Found, U.S. Navy Confirms".

- ^ "The Kennedys: A Relationship with Solomon Islands That Will Endure". Solomon Times (Honiara). 8 August 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Field, Michael (8 August 2023). "Caroline Kennedy meets children of Solomon Islanders who saved JFK's life". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Caroline Kennedy (1 August 2023). "Transcript: Ambassador Kennedy at a Ceremony Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of PT-109". U.S. Embassy in Canberra. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Prasad, Biman Chand and Kausimae, Paul (2012). Social Policies in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. The Commonwealth Secretariat. p. 21. ISBN 978-1849290838.

- ^ Tedder, James (2008). Solomon Island Years: A District Administrator in the Islands 1952–1974. Tautu Studies. p. 150.

- ^ Ogan, Eugene (1965). "An Election in Bougainville". Ethnology. 4 (4): 404. doi:10.2307/3772789. JSTOR 3772789.

- ^ a b Thompson, Roger (1995). "Conflict or co‐operation? Britain and Australia in the South Pacific, 1950–60". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 23 (2): 301–316. doi:10.1080/03086539508582954.

- ^ a b Goldsworthy, David (1995). "British Territories and Australian Mini-Imperialism in the 1950s". Australian Journal of Politics and History. 41 (3): 356–372. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1995.tb01266.x.