Contents

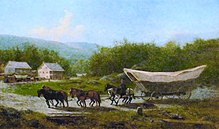

The Conestoga wagon, also simply known as the Conestoga, is an obsolete transport vehicle that was used exclusively in North America, primarily the United States, mainly from the early 18th to mid-19th centuries. It is a heavy and large horse-drawn vehicle which, while largely elusive in origin, originated most likely from German immigrants of Pennsylvanian Dutch culture in the Province of Pennsylvania in the early 18th century. The name "Conestoga Wagon" probably derived from the Conestoga River Valley settlement area in the province and saw usage as early as 1717, although it is not known whether the first wagons referred as such had similar builds as later Conestoga wagons.

Conestoga wagons are larger and more robust variants of covered wagons, sharing similarities in usage of white hemp cloths to cover the wagons, large wheels to travel on non-macadam road surfaces, and intended usage as vehicles to transport items elsewhere. It differs from most other covered wagon variants mainly by the curvature of the wagon body's sides and floor, which replicated boats, which served the purposes of keeping the luggage centered and looking visually pleasing to wagon customers. They were operated by a team of four to six horses of a now-extinct breed, a driver, and sometimes helpers. Conestoga wagons early may have been produced by farmers but later were often made by teams of blacksmiths, wheelwrights and wagon makers.

The specialized vehicles saw primary usage as transport vehicles that could have carried 6 short tons (5.4 t) to 8 short tons (7.3 t) of raw goods from rural areas to towns or cities of the eastern United States, typically bringing back commodified goods in exchange. Conestoga wagons were common presences in the northeast, especially Pennsylvania, as thousands of them may have traveled to different areas annually. Although it was sometimes used for westward frontier travel in the 19th century, lightweight and cheaper covered wagons were generally preferred by the pioneers. The Nissen wagon, likely deriving from Conestoga wagons, was also lightweight despite superficially resembling them and was a dominant vehicle type in the southeastern states compared to the heavyweight wagons. Conestoga wagon usage likely declined as a result of displacement by canals and railroads in the 19th century, which proved to be more efficient means of transporting goods elsewhere. Despite this, the cultural legacy of the Conestoga wagon endured in the later 19th and 20th centuries as they and other covered wagons became icons of early American history including pioneering, although the romanticized image waned by the 21st century.

Origin

The exact origins of covered wagons and the derivation of Conestoga wagons from earlier covered wagons remain not well known. The less adequately documented history of Conestoga wagons is in part due to the overall lack of specificity of the wagon types from early American colonists of the 18th century.[1] Knowledge of wagon production in colonial America originated from that of English and German immigrants of Great Britain and central Europe where a variety of wagon designs were already created. They also may have possibly brought early farm wagons with them as well. Wagons would have proven increasingly necessary in North America due to the need to haul farm goods and trade goods such as furs to other settlements such as Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania and to ports for Europe.[2]

There is no documented record of any strictly "first" Conestoga wagon to have ever been made. Covered wagon designs may have been standardized in design within colonial America, making it differ from the varied designs of English farm wagons of the 18th–19th centuries. They may have possibly derived from both English road wagons and large wagons of Germany although this remains speculative. The earliest documented usage of the American wagons was in 1716 when Philadelphia fur trader James Logan, who took over William Penn's business estate after his death, wrote in his account book the usage of an individual wagon by the wagoner John Miller for hauling goods from Philadelphia to the Conestoga River Valley in what is now Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Two other wagons were created and put to use by other individuals from the Conestoga valley named James Hendricks and Joseph Cloud, respectively in 1717. In November of the same year, Logan established a store for selling hardware and household goods to German settlers and Native Americans in Conestoga. Logan then purchased what he called a "Conestogoe Waggon" from James Hendricks in December 31, 1717, thus making this the earliest known mention of the wagon name.[2]

The name "Conestoga wagon" likely derived from the Conestoga River Valley, which was a settlement area for American colonists by the early 18th century that was about 45 mi (72 km) from Philedelphia and 60 mi (97 km) from Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[2] The earliest usage of the name "Conestoga" was previously applied to a river stream by the Bohemian merchant Augustine Herman in 1665, and it was also used as a name for the now-extinct Susquehannock tribe.[3] The slang term "stogie," used for long and cheap cigars made from rolled leaves and at times smoked by Conestoga wagoners, may have derived from the Conestoga wagon term.[1]

Farm wagons became increasingly prevalent in Philadelphia since after 1720, many of which were referred to as "Conestoga" or "Dutch" wagons.[4] Advertisements in The Pennsylvania Gazette indicate that the former term saw common usage by February 5, 1750 for a Philadelphia tavern named "The Sign of the Conestogoe Wagon." The synonymous term "Dutch Waggon" was also used for the location for another advertisement in the same newspaper publication in February 12, 1750.[5]

Description

General characteristics

The Conestoga wagon is a more robust variant of covered wagon (or prairie schooner) – it has the general characteristics of being a wooden wagon with both hickory bows on top to hold up a waterproof canvas and wooden wheels. Covered wagons are generally pulled by draft horses and act as both a transport vehicle and mobile home. They were specialized vehicles for transversing on rough roads, although walking or horse-riding would have been preferred in other circumstances by travelers. Although they generally made for uncomfortable travel experiences, covered wagons are considered by historians to have been vital to pioneer families whose possessions required long-distance travel while acting as temporary shelters for when the pioneers needed to sleep.[6] Wagoners did not ride inside the Conestoga wagons themselves; instead they either walked beside the wagon's team, rode on the backmost and left-sided horse (known as a "wheel horse"), or sat on the "lazy board" of the wagon's left side in front of its rear wheel.[7] The difficulty of Conestoga wagon travel was weighed largely on the road surface conditions, the poorer conditions leading to larger rolling resistance.[8]

Conestoga wagons derived in design from earlier covered wagons.[9] They had general boat-like shapes, their sides slanting outwards. The interior floors of the wagon type were slightly curved.[6] The wagons combined with three pairs of hauling horses could have measured up to 60 ft (18 m) long.[10] In the 18th century of the United States, the Conestoga wagon was the most popular transport vehicle of the American frontier, and as many as one hundred of them traveled in individual groups, extending in geographical range from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Augusta, Georgia. However, Conestoga wagon travel was still costly, so merchants often preferred transport of goods by sea. Depending on the weight load of the wagons, the terrestrial vehicles were transported by some four to six horses.[9] In comparison, American western frontier covered wagons were often transported by oxen instead of horses, but travelers tended to prefer the latter option.[11]

Early Conestoga wagons in the mid-18th century were smaller, consist of four draft horses for each wagon, and may have had been capable of carrying up to 1 short ton (0.91 t) of goods for hauling. The weight capacity of early Conestoga wagons is estimated, however, as none have survived to the modern day. The later, more advanced Conestoga wagons in comparison consisted of six draft horses individually and were capable of carrying up to 6 short tons (5.4 t) of goods for travel.[12] The largest Conestoga wagons may have been capable of carrying up to 8 short tons (7.3 t) of goods. Some Conestoga wagons had as many as 8 draft horses, but none ever had fewer than 4 of them.[13]

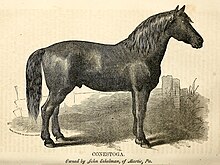

The Conestoga horse was a specialized breed of heavy and large draft animal as well as one of the few horse breeds to have originated from North America. The origins of the breed is unknown, but they probably originated from a few individual horses from Pennsylvania. They were popularly used because of their abilities to haul loaded heavy Conestoga wagons. Conestoga horses typically came in black or bay hair coat colors but were sometimes dapple gray. The Conestoga horse breed went extinct likely as a result of the decline of Conestoga wagon usage.[13]

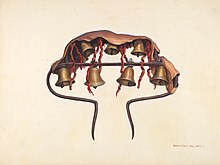

The pack horses were often equipped with bells, but when such a practice started is unknown. The bells are small-sized and are located on wearable "Conestoga bell arches," study iron pieces measuring 16 in (410 mm) to 20 in (510 mm). The lead horses (or front horses) often had five small bells, the middle horses four, and the pole horses (back horses) three larger ones for a total of twelve. The bell sounds coming from the Conestoga team was often seen by wagoners as a source of pride and them and may refine them for better tunes. Traditionally, a Conestoga wagon team that arrived without any bells on, usually the result of forfeiting them to another team as a result of needing assistance on a damaged or stuck wagon, was seen as a source of humiliation. The archaic American phrase "I'll be there with bells on" therefore derived from this now-obsolete tradition.[14]

Wagon body

The Conestoga wagon model is a uniquely American design with no close European equivalent, being well-suited for transversal through American roads that were not yet macadam, or built from hard stone. It is boat-shaped in terms of both crosswise (horizontal) and lengthwise (vertical) dimensions, thus ensuring the ability for sagging, or curving downwards in the middle, during movements through hills and valleys so that the loads remained centered.[15] However, the curvatures of the boxes could have also been for stylistic purposes, as consumers may have preferred their designs over those of straight-sided wagons.[16]

The wagon body of a Conestoga wagon, known also as a "box" or "bed," has a complex design compared to typically simple rectangular wagon boxes. The designs of the Conestoga wagon's body were intended to make the wagon last a long time and be flexible for traveling through roads that are normally rough for heavy-loaded vehicles. As a result, the Conestoga wagon is more representative in technological niches as a large-sized basket on a set of wheels than a box. Its designs were meant to replicate large-sized watercrafts that serve the dual purposes of carrying heavy quantities of goods and withstanding hostile environmental conditions such as currents. Historians George Shumway and Howard C. Frey considered suggestions by early United States history books that the Conestoga wagon boxes allowed for traveling passengers and goods across rivers to be nonsensical because the boxes would have leaked if placed in water bodies.[16]

The wagon bed is typically created from the hardy woods of white oaks (Quercus alba). It measures 16 ft (4.9 m) in length from its front to rear ends and never more than 4 ft (1.2 m) in width. Six to twelve hooplike hickory bows, reaching individual grounded heights of 12 ft (3.7 m), are arched over the wagon's bed to hold the white canvas sheet that covers them. The canvas, a cloth made from hemp fiber, was tied down to both sides of the wagon body but were left overhanging at both its front and rear ends. The white sheet measures approximately 24 ft (7.3 m) long. The positioning of the canvas serves to shield the wagon's contents from rainfall while allowing for air passages for cargo and passengers. The Conestoga wagon was extensively painted given the prominence of flair in Pennsylvania Dutch culture. The wagon box has light blue color tones whereas the ironworks were black and the wheels, running gear, and sideboards were vermilion in color.[15] The prominence of color in Conestoga wagons make it partially differ from other covered wagons, many of which had no painted colors due to concerns that draft animals were frightened by bright colors.[17]

On the left side of the Conestoga wagon is a short but strong white oak board known as the "lazy board." It is able to bear the weight of the wagon driver, or his helper if he hired one, who managed his draft animals plus team and operated the brake there. This meant that the driver had a habit of operating Conestoga wagons on the left side, starkly contrasting with modern operations of automobiles on the right. The heavy and sturdy brakes served to slow down the wagon's wheels when the driver held the iron handle (or "lock patent") down, and the handles were also used to lock the brakes. The brakes were vital for managing the wagon through unsmooth roads. The tongue, or a long board in the wagon's front area, may be plated in iron then painted.[18]

There are several other covered wagon variants, known from complete wagon evidence, that closely resemble the Conestoga wagon. The Weber wagon, utilized in the early 19th century, differs from typical Conestoga wagons in the presence of a front end panel and an almost vertical tail gate. Whether it and the similar Sternberg wagon and Shantz wagon can be considered Conestoga wagons is a matter of subjectivity according to Shumway and Frey.[19] On the other hand, the Groff wagon of the later 19th century, known by a single specimen, is clearly distinct from Conestoga wagons despite similar appearances in different constructions of the front end panel and lower sides. The "Sheibley wagon" has similar shapes to the Groff wagon but is classified as a Conestoga wagon because of the formatting of the wagon bed and bows.[20] The Nissen wagon is a distinct covered wagon variant originating from North Carolina that derived in design from the Conestoga wagon.[21] Therefore, Nissen wagons can superficially resemble Conestoga wagons, but the former differs from the latter in usage as lightweight carriage of people and items instead of as heavyweight carriage of goods and the presence of a box in the front area where a driver and a passenger could sit.[22] The Nissen wagon uses just two draft horses given its lightweight nature and is synonymous with the alternate term "Salem wagon."[23]

Running gear

The running gear of the four-wheeled Conestoga wagon is assembled into two parts. The first is the front portion, which contain the front wheels connected by the front axletree, front wagon hounds (parts binding the axles to the wagon), front wagon bolster (a wood beam connecting an axletree to the wagon body), and the tongue. The rear portion is made up of similar components, but instead of a tongue, it has a coupling pole (a beam connecting the front and back wagon axles). The front and rear portions are very similar in appearances, the differences being very specific.[24]

The axletrees are wooden and encased with iron coverings. The wagon's wheels are kept in place by iron linchpins to keep them in position. The rear brake mechanism can be handy for the covered wagons but are not required, hence the lack of them in some Conestoga wagons. The front hounds are made from oak wood and are the connecting piece between the wagon tongue and the front axletree. They are bound by a transverse oak and iron brace piece that can keep the wagon tongue up. The front hounds can also support the curved iron pieces that minimize sideways swaying and preventing toppling for the front wagon portion. The left front hound may also hold an iron sheath for an axe that wagoners can use to cut through wood obstacles or make new tongues and axletrees.[24]

The Conestoga wagon wheels were high so that the axles (or wheel centers) could clear through or move over low obstacles such as tree stumps and mud.[25] The wheels, equipped with iron tires, ranged in size in accordance to the wagon's size, the largest having been used for the Pitt wagon variants of the early 19th century for mountain-freighting. The rear wheels of large wagons on average have diameters between 60 in (1,500 mm) and 70 in (1,800 mm) while the front wheels were smaller and generally measured approximately 50 in (1,300 mm) in diameter. Medium-sized Conestoga wagon rear wheels meanwhile generally measure between 54 in (1,400 mm) and 60 in (1,500 mm) in diameter. The tires of large Conestoga wagon rear wheels usually measure 3.75 in (95 mm) to 4 in (100 mm) in width while those of medium Conestoga wagon rear wheels measured about 3 in (76 mm) in width. Conestoga wagons used for hauling and farming may have been complimented with different wheel size sets for performing different transversal duties, from small wheels for farms to large ones for road travel. Medium-sized wheels normally contain 14 spokes (or rods connecting to the wheel's center) while large wheels usually have 16 of them.[26]

Other accessories

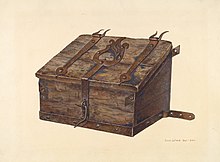

Additional accessories may be paired with the Conestoga wagon for utilitarian purposes. On the rear end of the wagon is a wooden trough known as the "feed trough" or "feed box" that wagon operators were able to remove, fill with grain, and place on the tongue to feed the draft animals.[25] Also present was a water bucket that was usually hung on the rear axletree, or an underside bar connecting two wheels, of the wagon.[27] Conestoga wagons may also be equipped with water barrels on the side, toolboxes for wagon-fixing, and a pot of tar for keeping the wheels moving.[28][27]

The feed box measures 5 ft (1.5 m) to 6 ft (1.8 m) long, approximately 12 in (300 mm) wide, and 10 in (250 mm) deep in dimensions. The top edges of the trough are embedded with light iron straps to prevent damage of it by the horses' teeth. The iron lug and pin of the feed box, positioned at the opposite ends of the trough from each other, are intended to fix the box's position at the tongue while the horses feed. The water bucket fills a similar purpose for consumption of water from nearby water sources by horses. The tar pot is wooden and had a lid with a central hole and a paddle for applying the tar to the wheels.[29]

In addition to the axe and toolbox which Conestoga wagons were equipped with, the wagon jack, used for raising wagons up, was another tool that was equipped on them, specifically probably in its rear end. They were highly durable and tended to have outlasted the wagons themselves, making them valuable for antique collectors. Trends around the size increase of wagon jacks is correlated directly with the increased size of the covered wagons.[29]

Production

Conestoga wagon production depended largely on the labors of blacksmiths and similar occupations since the colonial era of the United States, coinciding with increased land colonization and the rise of the American iron industry. The American iron industry was fueled by the abundant lumber from land-clearing that could be converted to charcoal and be used by blacksmiths to melt iron in furnaces into needed products. The American colonial iron industry was challenged by the British implementation of the Iron Act in 1750, which limited American production of cast iron and bar iron products. Nonetheless, pig iron (or crude iron) was still a prominent good within and near the Lancaster County of Pennsylvania.[30]

In the 18th century, farmers were expected to support themselves and their families by combined knowledge of farming and blacksmithing. Based on tax assessments in Lancaster County, the turn of the 19th century marked a shift towards specialized craftsmanship as wheelwrights and wagon makers became separate occupations from blacksmiths, all three of whom worked together to produce Conestoga wagons. Blacksmiths at times also hired apprentices to operate or produce tools. Blacksmiths used various tools such as vises, hammer and anvils, pliers, and drills to iron the wagon's gear and decorate the wagon bed. Early on, they built most of the wagon except for the wheels, but the wagon builder occupation later arose by the turn of the 19th century to help with the construction process.[30] The construction of the Conestoga wagon was a laborious process and required light but strong wood of pure qualities. Because of the long process and importance of the wagon in the United States, a finished product could have costed as much as $250 in 1820.[31]

Blacksmiths of high expertise were able to not only iron but decorate different elements of the Conestoga wagon such as toolbox lids. The tendencies by blacksmiths to decorate Conestoga wagons with motifs, often those of Pennsylvania Dutch culture such as tulips, hearts, serpents, and birds, are the result of competitive efforts to catch interest of their wagons by customers. Toolbox lids today are valuable collector's items for both museums and private collectors. Women played roles in Conestoga wagon production as well, using loom devices to weave simple canvas covers and ensuring that they fit with the corresponding wagons according to the wagons' sizes and the curvature of the wagon beds.[31]

By the time Conestoga wagons were commercially produced for the United States, the wagon makers individually tended to employ some 20 to 25 assistants in the construction process, but they did not strictly compose any single factory. Also, the Conestoga wagon was never completely standardized in design. Covered wagons resembling Conestoga wagons were built throughout the country, but true Conestoga wagon production, fairly organized in structure, was almost entirely restricted to eastern Pennsylvania. In the later 19th century in comparison, wagon shops in the United States tended to compose less than five workers total.[17]

Historic usage

Pennsylvanian origins

The region now known as Lancaster County was first permanently settled by European colonists, more specifically a Swiss Mennonite Conference group led by the religious leader Hans Herr, by 1719. The Ephrata Cloister religious community settled there in 1732 followed by the Amish around 1760. German immigrants arrived to Lancaster County within the 18th century because of the rich-quality land. The Pennsylvanian town of Lancaster was founded by John Wright in 1730 and grew to become one of the largest towns in the American colonies by the American Revolution. The German immigrants of the county referred to themselves as "Pennsylfawisch Deitsch," leading to the confusion by Englisher speakers who established the term "Pennsylvanian Dutch" despite them not actually being Dutch.[32]

By 1720, farm wagons were already put into usage within the British colony of Pennsylvania as they carried merchandise from Philadelphia to Lancaster county in exchange for furs.[4] In the mid-18th century, the German immigrants of Lancaster County produced their own Conestoga wagons for hauling crops elsewhere and for traveling on dirt roads. The covered wagons often carried flour and iron ores from Lancaster to Philadelphia in exchange for tools, clothing, and furniture.[32] They were also hauled from Conestoga, Pennsylvania to Philadelphia, where they returned to the former area with basic goods such as lead, gunpowder, rum, and salt.[33] Conestoga wagon usage was broadened to American settlers for pioneering west as time passed.[32]

Braddock Expedition

The Conestoga wagons were notably the major transport vehicles used during the Braddock Campaign of the French and Indian War. They were first referenced in relation to the war campaign by the Pennsylvania governor Robert Hunter Morris when he advised the Pennsylvania General Assembly that they cover the expenses of the wagons and horses to be employed for British-American military service to capture the French Fort Duquesne. Neither the Pennsylvania assembly nor those of Maryland and Virginia passed any law to cover military transport.[34]

The Major-General Edward Braddock arrived to North America in February of 1755 to carry out his role as commander-in-chief of the British forces during the French and Indian War.[35] Colonel Sir John St. Clair informed Braddock about settlers at the Blue Ridge Mountains who were running provisions and stores, expressing confidence that by early May of 1755, they would have 200 wagons and 1,500 pack horses ready for deployment into Fort Cumberland. Unfortunately for Braddock, only 25 wagons were deployed for the British frontier port by April, several of which were actually unusable. The major-general was aggravated in reaction to the underwhelming resources and wanted to shut down the expedition, but he later commissioned Benjamin Franklin to gather some 150 wagons and 1,500 pack horses from the locals. Franklin eventually succeeded in Braddock's demands but with great difficulty due to farmers being unable to afford giving up their resources and the Pennsylvania assembly having little interest in the war due to Quaker affinities. Another challenge was of building roads, as several road builders under Colonel James Burd were being killed by Native Americans, leading to many others threatening to quit their work unless they were given protection.[34]

Letters and newspaper accounts of the 1750s confirm the usage of farm wagons during the Braddock Expedition that were referred to as "Conestoga wagons." No wagon of the war campaign survives today, but archeological evidence of wagon fragments provide limited evidence of the wagon designs. The wheel diameters are typical of farm wagons rather than military vehicles, and the presence of strakes for wagon wheels indicate the lack of brakes in early farm wagons that later Conestoga wagons had. The wagons used by Braddock's men also carried smaller loads compared to later Conestoga wagons due to their smaller sizes.[36]

According to the British Army officer Robert Orme, the wagons, artillery, and carrying horses were placed into three different divisions that were each overseen by an appointed superior. The wagon masters of each division were expected to keep their teams stable and replenish horses when needed. During the expedition, many wagons sustained critical damage and were replaced by wagons from other camps. Management of horses also proved problematic as they were often lost or brought home by their owners, and those that remained grew weaker over time. Some wagons had to be sent back due to being too heavy, and the others had loads removed in order to reduce their weights.[35]

The Braddock Expedition ended with the Battle of the Monongahela, which ultimately proved to be disastrous for the British Army. Many of Braddock's soldiers were killed or wounded by the opposing French and their allied Native American forces, and Braddock himself was mortally wounded. Most of the British artillery, wagons, and supplies were abandoned by the British army as they quickly retreated, meaning that a majority of the remaining wagons were lost. Most of the wagons at Dunbar's Camp were burned by the British to prevent the French and Native Americans from seizing their materials as they anticipated pursuit by the enemy forces. Only a few wagons of the Braddock Expedition ultimately remained, and they were returned to their original owners when the vehicles arrived at Wills Creek in Pennsylvania. Both the owners who their wagons and/or horses returned to and those who did not due to their being lost were compensated for accordingly.[35] In total, 156 wagons are thought to have been employed for the disastrous Braddock Expedition, the only wagon to survive intact being that of William Douglas.[37]

Late 18th–19th centuries

Conestoga wagons, strictly speaking, are generally thought to have had widespread usage within North America lasting from 1750–1850, although the year range is by no means strict. Several authors argued that the "golden age" of Conestoga wagons (or time of peak usage) lasted from 1820 to 1840.[17][38] As the main terrestrial vehicles of transport in North America, they frequently hauled farm goods from rural areas into towns and cities in exchange for other manufactured commodities.[39][40] The increase in usage of Conestoga wagons within Pennsylvania in the later 18th century was correlated with the growth population in the western region and the rising economic development of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. From 1750 up to 1775, more than 10,000 Conestoga wagons traveled within the Pennsylvania region to Philadelphia annually, and 50 to 100 wagons traveled daily. At times, a whole train of 100 wagons traveled at once.[41] Wagon travel was made possible by the construction of roads across multiple provinces to make travel easier and forts within the Pennsylvania mountain front to protect settlers from Native American raids, as diplomatic relations had been damaged due to the French and Indian War.[42] Some of the most significant roads included the Conestoga Road and the Great Wagon Road.[43]

Beginning in the early 19th century, wagons became larger as evident by the size increase of the wagon jacks over time. They were also hauled across rivers such as the Susquehanna River via ferry boats, and heavy wagon traffic for ferrying had resulted in wagons waiting in line for up to three days.[43] It was used to some extent for travel to the western frontier, but it was generally too heavy, required too many draft animals for hauling, and was an expensive vehicle to build or purchase. Standard "prairie schooners" were much more often used since they were lighter, had sturdier wheels, and were cheaper.[41] The perception of Conestoga wagons being the preferred vehicle of choice for traveling westward in North America is seemingly the result of them being better-represented in literature and media compared to the smaller prairie schooners.[44] Still, by the 1840s, the Conestoga wagon saw usage in the Santa Fe Trail, being distinguished in purpose from the medium and light covered wagons used by settlers migrating to California or Oregon.[45] Conestoga wagons saw also some usage by German immigrants of the British provinces of what is now Canada as well, typically carrying 8 short tons (7.3 t) of goods, and roads were built to accommodate wagon travel.[46]

Wagoners, especially in Pennsylvania, often stopped by at taverns, also at the time called "stations." From Chambersburg, Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh, there were about 150 taverns, or roughly 1 tavern for each mile.[43] The inns of the 19th century often contained large signs containing painted figures and words that were mounted on posts at the highway to catch the attention of wagoners, including those who were illiterate. The taverns were numerous, but not all of them welcomed wagoners in for service.[47] In the winter, the wagons were parked on planks so that the wheels would not freeze while the wagoners stayed in overnight.[43] The taverns were normally crowded on busy days, and wagoners may have expected greetings from other tavern guests, ranging from fellow wagoners to community members meeting up there. Tavern keepers, generally influential men of their communities, made profits from selling liquor and meals to them, but their revenue mainly came from overnight stays, which would have costed less than $1.75. The next morning, wagoners followed typical schedules of eating breakfast then tending to their horses (i.e. feeding and watering them) before departing.[48]

Decline

The Conestoga after having seen a long time of usage in North America gradually declined in usage in the latter half of the early 19th century as part of a technological turnover against the slower and more costly vehicle. This was especially case in the state of Pennsylvania where the covered wagons originated from, as the introduction and spread of canals provided means to cheaper and faster transportation of goods. Another major factor to the decline of the Conestoga wagons was the construction of railroads, as companies such as the Reading Company were more efficient for hauling goods from the coal industry or agricultural shipping. As a result, Conestoga wagon usage later became largely restricted to rural areas.[49] The displacement of Conestoga wagon usage by railroads and canals in the United States was a national trend.[50] Despite the replacement of the Pony Express mail service and most wagons by more advanced technological services, the US horse population did not decline in correlation.[51]

The decline of the Conestoga wagon and most other covered wagons in the later 19th century did not reflect the decline of all covered wagon variants, however. The Nissen Wagon, originating from North Carolina,[21] was still a popular transportation vehicle throughout the 19th century and was manufactured in large numbers in reflection of such high demands.[52] They were still produced in high numbers by the Nissen Wagon Works in the early 20th century for southeastern states but declined in usage by the 1940s.[53]

Legacy

By the American Civil War, Conestoga wagons were viewed in a romantic light by Americans. Several poems about Conestoga wagons and their wagoners were produced, such as "The Wild Wagoner of the Alleghenies" by Thomas Buchanan Read in 1863 and "Wagoning" by H. L. Fischer in 1888. There were many wagoner-based songs that were produced within the 19th century. "The Wagoner's Curse On The Railroad" was a song sung in reflection of the saddened and disgruntled wagoners whose ways of life were displaced by the rise of the railroads.[54] A brief 1937 poem for The Denver Post made a comparison of covered wagons and the more recent autotrailers, drawing upon the mythical status of Conestoga wagons to promote an autotrailer camping craze. However, the camping wagons failed to make the same cultural impacts that covered wagons had.[6][55]

The legacy of the Conestoga wagon endured as a symbol of the early United States, being viewed in romantic light along with regular covered wagons in the 20th century. The popular image of the Conestoga wagon was roughly comparable to that of another American horse-drawn vehicle called the Concord coach.[56] The Covered Wagon, a silent film released in 1923 was amongst the earliest cases of covered wagons in 20th century popular culture. The Little House on the Prairie book series features a Conestoga wagon that was owned by the Ingalls family. The cultural depictions of the covered wagons represented American values of pioneering in its early history.[6] The Conestoga wagon is also featured in tradition in the form of a sports trophy that the football teams of both Dickinson College and Franklin & Marshall College had both competed for since 1963, and the wagon model of the trophy is meant to represent a Conestoga wagon that had transported the teams of both colleges back in 1889.[57]

In the modern day, the legacy of Conestoga wagons declined mostly to books, paintings, and historical artifacts held by museums and private collections. Nonetheless, they have been preserved to tell American history and establish appreciation for historical relics. [58] The National Museum of American History, as an example, featured a Conestoga wagon to encourage children to wonder about 19th century American family lives within the wagons, especially their struggles.[59]

References

- ^ a b Coulson (1948), pp. 215–217.

- ^ a b c Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 14–16.

- ^ Frey (1930), pp. 289–290.

- ^ a b Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Berkebile (1959), pp. 144.

- ^ a b c d Tyler (2010), pp. 13–19.

- ^ Clark (2017), pp. 5.

- ^ Elis, Haber & Horrillo (2023), pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Reich (2010), pp. 154.

- ^ Reist (1975), pp. 14–17.

- ^ White, Jr. (1965), pp. 194.

- ^ Clark (2017), pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Herrick (1968), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Herrick (1968), pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 185–187.

- ^ a b c McCord (1970), pp. 661–663.

- ^ Frey (1930), pp. 295.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 214–224.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 237.

- ^ a b Terry & Robertson (1985), pp. 25–27.

- ^ National Park Service (1984), pp. 8.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 254–256.

- ^ a b Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 197–200.

- ^ a b Herrick (1968), pp. 156–158.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Clark (2017), pp. 4.

- ^ Simpson (2013), p. 53–54.

- ^ a b Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 207–213.

- ^ a b Reist (1975), pp. 21–26.

- ^ a b Reist (1975), pp. 39–44.

- ^ a b c King (1996), pp. 319–321.

- ^ Reist (1975), pp. 18–26.

- ^ a b Berkebile (1959), pp. 142–143.

- ^ a b c Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 35–45.

- ^ Berkebile (1959), pp. 144–146.

- ^ Berkebile (1959), pp. 149.

- ^ Wilkinson & Beyer (1997), pp. 1–6.

- ^ Clark (2017), pp. 8.

- ^ Hart & Wilson (2016), pp. 145–146.

- ^ a b Herrick (1968), pp. 159–161.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 61–63.

- ^ a b c d Clark (2017), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Pertermann & Carr (2022), pp. 408–409.

- ^ McLynn (2002), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Bradford (2015), pp. 31–33.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 79–80.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Herrick (1968), pp. 161.

- ^ Frey (1930), pp. 311.

- ^ Brynjolfsson & McAfee (2015), pp. 9.

- ^ Bricker (2013), pp. 112.

- ^ Clark (2017), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Shumway & Frey (1968), pp. 87–108.

- ^ Wallis (1997), pp. 36–38.

- ^ Herrick (1968), pp. 161–162.

- ^ Adamovage (2023).

- ^ Clark (2017), pp. 11.

- ^ Barnes (2015), pp. 320.

- Barnes, Donna R. (2015). "Chapter 33: Playful Experiences for Children in Museums". In Fromberg, Doris Pronin; Bergen, Doris (eds.). Play from Birth to Twelve: Contexts, Perspectives, and Meanings (3rd ed.). pp. 319–328.

- Bradford, Robert (2015). Keeping Ontario Moving: The History of Roads and Road Building in Ontario. Dundurn Press.

- Bricker, Michael (2013). Historic Forsyth County. Arcadia Publishing.

- King, Linda J. (1996). "Lancaster (Pennsylvania, U.S.A.): Pennsylvania Dutch Country". In Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul (eds.). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. pp. 319–321. doi:10.4324/9781315073828-80.

- McLynn, Frank (2002). "Chapter 3: To Boldly Go". Wagons West: The Epic Story of America's Overland Trails. Grove Press. pp. 49–91. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Reich, Jerome R. (13 June 2010). "Chapter 14: Commercial Commerce". Colonial America (6th ed.). Routledge. pp. 147–156. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Reist, Arthur L. (1975). Conestoga Wagon – Masterpiece of the Blacksmith. Brookshire Printing. pp. 1–50.

- Shumway, George; Frey, Howard C. (1968). Conestoga Wagon 1750–1850: Freight Carrier for 100 Years of America's Westward Expansion (3rd ed.). George Shumway. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Simpson, Wilma Hicks (12 March 2013). Greater Than the Mountains was He: The True Story of Johann Jacob Shook of Johann Jacob Shook of Haywood County, North Carolina. Tate Publishing. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Terry, George D.; Robertson, Lynn (1985). Carolina Folk: The Cradle of a Southern Tradition. University of South Carolina Press. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Wallis, Allan D. (19 June 1997). Wheel Estate: The Rise and Decline of Mobile Homes. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Journal articles

- Berkebile, Don H. (1959). "Conestoga Wagons in Braddock's Campaign, 1755" (PDF). Contributions from The Museum of History and Technology. 9 (218): 142–153.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik; McAfee, Andrew (2015). "Will Humans Go the Way of Horses?". Foreign Affairs. 94 (4): 8–14.

- Clark, Ron (2017). "The Rise and Fall of the Conestoga Wagon or the Little Covered Wagon in the Barn". Academia.edu: 1–18.

- Coulson, Thomas (1948). "The Conestoga Wagon". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 246 (3): 215–222.

- Elis, Roy; Haber, Stephen; Horrillo, Jordan (2023). "Transport Corridors" (PDF). Long-Run Prosperity Working Paper Series, Hoover Institution: 1–37.

- Frey, Howard C. (1930). "The Conestoga Wagon" (PDF). Journal of the Lancaster County Historical Society. 34 (13): 289–312.

- Hart, Victor A.; Wilson, Jason L. (2016). "Clark's Ferry and Tavern: Gateway to the Juniata Valley". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 83 (2): 135–158. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.83.2.0135.

- Herrick, Michael J. (1968). "The Conestoga Wagon of Pennsylvania". Western Pennsylvania History. 51: 155–163.

- McCord, Carey P. (1970). "Wains and Wainwrights: Wagon Making as an Occupation". Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 20 (5): 661–665. doi:10.1080/00039896.1970.10665680.

- Pertermann, Dana L.; Carr, Bradley J. (2022). "To Preserve the Struggle: Digitizing the Oregon Trail". Historical Archaeology. 56: 407–416. doi:10.1007/s41636-022-00361-4.

- White, Jr., Lynn (1965). "The Legacy of the Middle Ages in the American Wild West". Speculum. 40 (2): 191–202. doi:10.2307/2855557.

Other sources

- Adamovage, David (28 September 2023). "Devils and Diplomats Under the Friday Night Lights for the Wagon". Dickinson Athletics. Archived from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- National Park Service (31 December 1984). National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form (PDF) (Report). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Tyler, Lindsay Elaine (2010). Mobile/Home: The Trailer As America (MA). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum & Parsons School of Design. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- Wilkinson, Norman B.; Beyer, George R. (1997). The Conestoga Wagon. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. pp. 1–6.