Contents

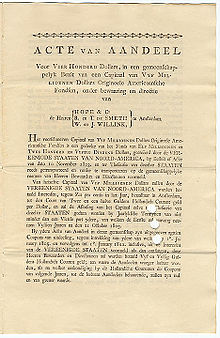

Hope & Co. was a Dutch bank that existed for two and a half centuries. The bank was located in Amsterdam until 1795; originally it concentrated on Great Britain. From 1750 it played a major part in the finances of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) through Thomas Hope and his brother Adrian. During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763) the Hope brothers profited from the Netherlands' neutral position and became very wealthy. The Hopes became heavily involved in the Dutch Caribbean, and Danish West Indies.[1] They specialised in plantation loans, in which the entire produce of the plantation was remitted to the lender, who would supervise its sale in order to secure repayment. In this way, the Hopes helped the plantation economy to become integrated into a global network of financiers and consumers.[2] The Hope family were among the richest in Europe at the time. The family business focused on financing commercial transactions and especially on issuing money loans to monarchs and governments in Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Russia, Portugal, Spain, France and America. The bank was famous for having Catherine the Great as their client and Adrian supplied her several times with diamonds.[3]

History

Six of eight sons of the Scottish merchant Archibald Hope (1664–1743) – Archibald Jr. (1698–1734), Isaac, Zachary, Henry, Thomas (1704-1779), and Adrian (1709–1781) – were merchants of trade. They were active in shipping, storage, insurance, and credit in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. In 1720 they barely survived the bubble that led to the passage of the Bubble Act in London.[4] Archibald and Henry invested in the Provinciale Utrechtsche Geoctroyeerde Compagnie (1720-1752).[5] Charles Hope, 1st Earl of Hopetoun was a cousin.[6]

In this early period the Hope brothers made money organizing shipment for Quakers and Swiss Mennonites out of Rotterdam (under the direction of Archibald, Isaac and Zachary). The top years for the transport of migrants to Pennsylvania were 1738, 1744, 1753 and 1765. These transports were paid for by the city of Rotterdam and the local Mennonite church.[7]

In 1743 the brothers inherited a fortune from their father. For many years the brothers traded with Saint Petersburg, Bilbao, Cadix and Sint Eustatius which became a free port in 1756.[8] The Hopes traded in sugar, cocoa beans, tobacco and timber, especially sailing masts from the Baltic states.[9] In 1750, Stadtholder William IV appointed Thomas as his representative in the meeting of directors of the West India Company (WIC), but it ended the year after when all the appointments were reverted.[10] In 1752, he became a member of the "Lords XVII", the managers of the VOC. Four years later Thomas represented Anne of Hanover in the VOC. The company moved to Keizersgracht in 1758. The firm operated as agents to the British government which supplied loans to Frederick the Great during the Seven Years' War.[11] The turnover raised from 10 to 37 million between 1755-1762.[12] In October 1759 and March 1760 the Hope brothers bought at auction from the Dutch East India Company a massive 595,879 pounds of tea, at a cost of more than one million guilders. There is no doubt that they intended to flood the North American market.[13]

In 1762 when Jan (John) and his nephew Henry Hope (1736–1811) joined Hopes, the name was changed to Hope & Co and a new era began. From that time the firm concentrated on banking.[4] They expanded the offices in Amsterdam, totalling 26 people. Their turnover reached 47 million guilders in 1762. This peak was followed by a sharp decline in 1763 and 1764, when the figures were 42 and 33 million guilders respectively.[15] During the Amsterdam banking crisis of 1763 Hope & Co helped out Leendert Pieter de Neufville. Henry's first substantial foreign loan was to Adolf Frederick of Sweden in 1768; in the next twenty years, Sweden was to borrow a total of 15 million guilders (securitised foreign loans); in 1770-1771 to the kings of Bavaria and Prussia.[16]

The Hope Company cooperated with Alexander Fordyce and Gurnell, Hoare, & Harman in 1770.[16][17][18] In 1771 George Colebrooke and James Cockburn, directors of the EIC, recruited Paul Wentworth (spy) to borrow £66,000 from Hope & Co. In 1771 Adrian Hope bought together with Andries Pels negotiaties for 904,000 guilders.[19] Hope & Co suffered from the crisis of 1772 and the fall of the EIC-stocks. The turnover with the Amsterdam Exchange Bank plummeted from more than 50 million guilders in 1772 to 30 million in 1773.[20] In 1774 Fordyce was forced to sell his estate to Sir Joshua Vanneck, 1st Baronet; the plaintiffs were Hope & Co and Harman and Co.[21][22][23] George Colebrooke went bankrupt.

Though primarily interested in trade deals from the start of their activities, the Hope brothers expanded their interests to longer-term investments in land and the arts. During the 18th century Hope & Co. set up a profit sharing agreement for the partners to reduce the risk of bankruptcy of the entire firm due to the indiscretions of one member, as happened in the case of rival banking house Clifford in 1772.[4] In order to become partner in the profit sharing scheme, the member had to learn the special Hope & Co. bookkeeping method developed by Adrian Hope, who had assisted filing the Clifford bankruptcy.[24]

In March 1781 Adrian Hope died without offspring; the heirs paid a small amount on inheritance tax, which was regarded as fraud.[25] Hope & Co. threatened to move the company to Ostend. The company lend an enormous amount of money to Charles III of Spain. For Spain Hope organised state loans for nine million guilders in the 1780s.

The adopted John Williams joined the Hope company in 1782. The company supplied Frederick VI of Denmark with money, a plantation on Saint Croix served as collateral;[26] in 1786 they supplied a loan to Stanisław August Poniatowski. In 1785 Nicolas Bauduoin (-1787) and Jan Caspar Hartsinck were members in the board; two years later Hartsinck was appointed in the city council by the stadtholder and in the Bank of Amsterdam.[27] In the summer of 1789 when the French population suffered from famine Jacques Necker intervened personally and successfully at Hope & Co. to supply Louis XVI with grain.[28][29] The 2.4 million in the royal treasury he used as a collateral.[30] Between 1787 and 1794 the company lost million of guilders in a deliberate effort to manipulate the price of cochineal from Mexico.[31]

In January 1790 Thomas Hope (designer) was admitted to the board of the Hope company; he owned almost a sixth of the shares, but preferred to travel to Italy, and Pierre César Labouchère became a partner.[a] Labouchère played an important role in negotiations with France, handling most of the financing for Holland with that country.[32] In 1792 Alexander Baring started to work at Hope & Co.[b] In November 1792, French Minister of Finances Étienne Clavière harshly pointed out that Hope & Co. was the leading member of a group of bankers engaged in speculation against the French credit and currency.[33] Between 1788 and 1794 Hope & Co. issued loans totalling 53 million guilders on behalf of the Russian Empress.[34][35] Early 1795 all the Hopes had fled to London to avoid the Batavian Revolution and the French occupation of the Netherlands and never came back. Their stock in warehouses was shipped to Hamburg? In 1796/97, after the Third Partition of Poland Robert Voûte, an employee, went to Saint Petersburg; by buying up Polish bonds prudently in 1798, the partners of Hope & Co. made a huge profit.[36] Then Hope & Co supplied loans to Portugal (to Rodrigo de Sousa Coutinho and John VI of Portugal).

In 1803, the bank was involved in financing the Louisiana Purchase.[37] The Hope brothers sold the real estate at Keizers- and Prinsengracht to John Williams Hope. Also Henry sold Villa Welgelegen to his fiduciary, who continued to hold that office until the establishment of the monarchy under Louis Bonaparte in 1806. When Henry Hope died in 1811, the London offices of Hope & Co. merged with Baring Brothers & Co.[38] Adriaan van der Hoop inherited the Amsterdam portion of the investments, together with Alexander Baring.[39]

Art collection

Thomas Hope was a member of the China-committee and likely started to collect blue and white Chinaware.[40] In 1770 the mansion was renovated and in 1771 they acquired a fine collection of paintings from two Mennonite brothers in Rotterdam. Both Jan, supported by his wife, and Henry collected paintings, statues and Loosdrechts porcelain.[41] In 1783 Jan Hope sued the painter Louis Gerverot.[40] Around 1790 John Williams Hope was portrayed by Angelika Kaufmann.

When Pichegru occupied the south Henry fled from Hellevoetsluis on 17 October 1794.[42] Henry took as much art he could ship according to August Schlegel.[43] The paintings that were too large to take to London and which remained in the possession of the bank, came into the hands of Adriaan van der Hoop. Henry settled on the corner of Harley Street and Cavendish Square.[44] Thomas Hope of Deepdene was collecting art, sculptures, antique vases and books in Duchess Street. His son Henry Thomas Hope inherited the collection after 1831. Lord Francis Pelham Clinton-Hope sold the Hope Collection of Pictures in 1898.

Archive

The Hope archive (1725–1940), at the Amsterdam City Archives, is an important source for the history of Amsterdam and the Netherlands as the center of world commerce in the 18th century.[46] The archive of Thomas Hope is mixed up with the archive of Jean Chrétien Baud because of the latter's interest in the Dutch East India Company.[47][48]

Unlike banks today, the partners of Hope & Co. mixed up their private business with public business and the bank's business. Letters in the archive touch on many subjects at once. A particularly rich portion of the archive is the correspondence in the period 1795–1815, when Henry Hope was forced to leave the Netherlands and set up offices in London. The regular correspondence between the Amsterdam and London branches give important insights into trade negotiations of the period and how they were done.

Hope family

In many historical documents, this bank is referred to as simply "Hopes" and sometimes "Hopes of Rotterdam" or "Hopes of Amsterdam".

| Archibald I (1664–1743) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archibald II (1698–1734) | Henry Sr (1699–1737) | Isaac (1702–1767) | Thomas Hope | Adrian (1709–1781) | Zachary (1717–1770) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Henry Hope | Oliver (1731-1783) | Jan Hope | Archibald III (1747–1821), WIC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John Williams Hope (1757–1813), adopted | Thomas Hope (designer) | Adrian Elias Hope (1772-1834), gardener | Henry Philip Hope, collector | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Later years

In the 19th century Hope & Co. specialized in railway investments in the United States and Russia. In the 20th century the emphasis shifted from international transport to Dutch investments. From 1885 Hope & Co. cooperated and in 1937, Hope & Co. acquired Van Loon & Co., formerly Wed. Borski.[34] In 1966 Hope & Co. merged with R. Mees & Zoonen to form Mees & Hope. In 1969, the Company merged with Nederlandse Overzee Bank. Ultimately, it was bought by ABN Bank in 1975. After the merger of ABN Bank and Amro Bank to form ABN Amro, Bank Mees & Hope merged with Pierson, Heldering & Pierson (then wholly owned by Amro Bank) in November 1992 into MeesPierson and was subsequently sold to Fortis. It subsequently became part of ABN Amro again when Fortis failed and Fortis' Dutch businesses were re-established as ABN Amro.

Notes

- ^ Pierre's marriage in 1796 to the third daughter of Francis Baring, Dorothy, was the cement between the two firms Barings and Hopes.[4]

- ^ Alexander Baring was in charge of joint operations led by Baring & Sons and Hope & Co. in the United States of America.

References

- ^ M.G. Buist, p. 12

- ^ "Adrian Hope of Amsterdam (1709 - 1781)".

- ^ Amsterdam City Archives; [1]

- ^ a b c d Buist, Marten Gerbertus (1974). At spes non fracta: Hope & Co. 1770-1815. Merchant bankers and diplomats at work. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-1629-2.

- ^ Slechte, C.H. (1998) De firma list en bedrog : de Provinciale Utrechtsche Geoctroyeerde Compagnie (1720-1752). In: Jaarboek Oud-Utrecht, p. 188. ISSN 0923-7046.

- ^ M.G. Buist, At Spes non Fracta: Hope & Co, p. 5

- ^ Empty Contract Promises Will Be Without Guarantee In Heaven by Michael Meade, p. 118

- ^ Barbara W. Tuchman (1988) The first salute

- ^ A.C. Carter (1971) The Dutch Republic in Europe in the Seven Years War, p. 110

- ^ J. Elias, p. 943

- ^ J. Jonker, p. 119

- ^ Elias, J. De vroedschap van Amsterdam, p. 1061

- ^ That Abominable Nest of Pirates St. Eustatius and the North Americans, 1680–1780 by VICTOR ENTHOVEN (2012) p, p. 286

- ^ Sotheby

- ^ M.G. Buist, p. 11

- ^ a b Elias, J. De vroedschap van Amsterdam, p. 1059

- ^ Amsterdam City Archives on 3 July 1770, NA 5075, nr. 426

- ^ J. Clapham (1944) The Bank of England, p. 249

- ^ https://archief.amsterdam/archief/5075/12400 dd 21 November 1771, p. 143-147

- ^ At Spes non Fracta: Hope & Co. 1770–1815 by M.G. Buist, p. 22

- ^ Information 1794, p. 64

- ^ The Town and Country Magazine, p. 669

- ^ Frank Brady, p. 37

- ^ Solutien aan den Hove van Holland overgegeeven

- ^ G.J. van Hardenbroek, Gedenkschriften, deel III, p. 71

- ^ https://archief.amsterdam/archief/5075/12478 26 July 1785

- ^ M.G. Buist, p. 38

- ^ At Spes non Fracta: Hope & Co. 1770–1815, p. 46 by M.G. Buist

- ^ Othénin d'Haussonville (2004) "La liquidation du 'dépôt' de Necker: entre concept et idée-force,", p. 156 Cahiers staëliens, 55

- ^ Neckers Charakter und Privatleben: nebst seinen nachgelassenen ..., Band 1, p. 83

- ^ J. Jonker & K. Sluyterman, p. 100

- ^ J. Jonker & K. Sluyterman, p. 140

- ^ Niccolò Valmori (2016) Private interest and the public sphere: finance and politics in France, Britain and The Netherlands during the Age of Revolution, 1789-1812, p. 135

- ^ a b NRC Handelsblad 25-10-1989

- ^ J. Jonker & K. Sluyterman, p. 122

- ^ M.G. Buist, p. 29

- ^ Archief van de Firma Hope & Co. met verwante archiefvormers

- ^ Titcomb, James (23 February 2015). "Barings: the collapse that erased 232 years of history". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ J. Knoef, 'De verzamelaar A. van der Hoop', _Jaarboek Amstelodamum_ (1948) 50-72

- ^ a b Zappey, W.M. (1988) De Loosdrechtse porseleinfabriek 1774–1784. In: Blaauwen, A.L. den, et al. (1988) Loosdrechts porselein 1774–1784.

- ^ J.W. Niemeijer, 'De kunstverzameling van John Hope (1737-1784)', Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 32 (1981), p. 127-232

- ^ At Spes non Fracta Hope & Co.,p. 43, 49

- ^ "Ontdek kunstverzamelaar Henry Hope".

- ^ Amsterdam City Archives 735-2895

- ^ Niccolò Valmori (2016) Private interest and the public sphere: finance and politics in France, Britain and The Netherlands during the Age of Revolution, 1789-1812

- ^ "Archive of the company Hope & Co". City archive Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ 1.10.46 Inventaris van het archief van T. Hope

- ^ 2.21.007.58 Inventaris van het archief van J.C. Baron Baud en aanverwanten, (1585) 1804-1985

Sources

- Buist, M.G. (1974), At spes non fracta: Hope & Co. 1770–1815. Merchant bankers and diplomats at work., The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, ISBN 90-247-1629-2.

- Jonker, Joost & Pieter Bastiaan (1997), The link between past and future: 275 years of tradition and innovation in Dutch banking, Amsterdam: MeesPierson, ISBN 90-901073-0-4.