Contents

International Hat Company, formerly named the International Harvest Hat Company, was a St. Louis, Missouri-based manufacturer of commercial hats and military helmets.[9] The company was one of the largest hat manufacturers in the United States and, at one time, the largest manufacturer of harvest hats in the world.[6] It is best remembered for its design and mass production of tropical shaped, pressed fiber military sun helmets for service members of the United States Army, Marines, and Navy during and after World War II. Additionally, the American owned company was a major producer of harvest hats, straw hats, fiber sun hats, enameled dress hats, baseball caps, and earmuffs throughout most of the 20th century. However, it is the International Hat military sun helmets that have become the most notable collector's items.

Established in 1917 as a private corporation, the company began with a single product line of harvest straw hats.[3] By the late 1930s, the company had expanded into fiber pressed sun hats and leather harvest hats.[3] During World War II, International Hat developed and produced several models of military sun helmets, including a model with rudimentary ventilation.[10] After the war, the company became interested in plastic molding injection, moving increasingly away from pressed fiber. In the 1950s, General Fibre Company, a subsidiary of International Hat, changed its name to General Moulding Company to reflect these production changes in basic materials. By the 1960s, International Hat was mostly producing baseball caps, straw hats, earmuffs, plastic helmets, and plastic sun hats. During this era of expansion, the company had a proclivity for building its factories in small rural cities, often becoming the largest employer and economic backbone of those communities.[11][12] On several occasions, International Hat donated land or facility equipment for the creation of municipal parks located adjacent to one of its factories, namely for the purpose of benefiting employees, their families, and the local community.[13]

After sixty-one years of business, the company was sold in 1978 to Interco, Inc., where it continued operating as a subsidiary.[14][15] In 1988, Interco was the target of a hostile takeover bid. Consequently, International Hat was divested the following year to Paramount Cap Company, as part of a debt restructuring plan instituted by the parent company.[5] However, Interco subsequently went bankrupt in 1991, after selling 16 of its 20 subsidiaries.[16] Although International Hat was liquidated, several of its original factories are still in operation by other hat companies in Southeastern Missouri.[5][17] Additionally, one of International Hat's warehouses in the historic district of Soulard, Missouri has been added to the National Register of Historic Places.[1][18] International Hat operated the historical building from 1954 to 1976.[2] It is presently used as a senior and disabled living facility.[1]

History

First location and early company history

The company was founded by Isaac Apple on August 17, 1917, as International Harvest Hat Company.[3] The prominent St. Louis families of Apple and Tilles incorporated International Harvest Hat during the turbulence of World War I.[4] The Apple family had previously founded the Apple Hat Company, which was based in Fort Smith, Arkansas.[19][20] Among the co-founders of International Harvest Hat was George Tilles, Sr., whose sister Hannah, was married to Isaac Apple.[20] However, the elderly Tilles left operational management of the company to his brother-in-law Isaac Apple.[21] The other original minority shareholders at the time of incorporation included Alexander E. Rosenthal, Harry J. Talbot, and John C. Talbot.[22] Rosenthal, who had previously been at the Apple Hat Company, was appointed as the first general manager of International Harvest Hat.[23] However, in 1918, he was arrested in Galveston, Texas on charges of embezzlement for the unauthorized sale of nineteen bales of harvest straw hats.[23]

The original business model of the company was commercial hat production of harvest straw hats.[3] On the micro-economic level, St. Louis had become a center of hat manufacturing during the Second Industrial Revolution.[24] In 1900, 129 businesses in St. Louis were producing custom hats for women, with approximately 600 employees in the industry.[24] Within the decade, St. Louis was the fifth largest producer of fur felt hats.[24] International Harvest Hat proposed to do the same thing for straw harvest hats, by ramping up production capacity and challenging the manufacturing centers in Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey.[24] The timing of market entry was favorable to the company's goals, as the organization was established at the peak decade of the commercial hat apparel market. In 1910, over 42 million hats were produced in the United States, an all-time record for domestic production.[25][26]

On the macroeconomic level, the company was founded at a time of ascendance for the United States. In 1916, the United States economic output, for the first time in history, was greater than that of the British Empire, establishing the United States as the world's largest economic superpower.[27] From World War I to the beginnings of the Great Depression, it was under these economic environmental conditions that the company originally produced a product line of harvest hats. Such hats of the period were a staple of farmers and field hands across the US.[21] By the 1920s, St. Louis replaced New England as the world's dominant manufacturing center for harvest hats.[28] International Harvest Hat was a major contributor to this regional shift in industrialization. By the early 1920s, the company had become the largest industrial producer of harvest hats in the world.[6] In 1928, the company produced over 36,000 per day and approximately 9.4 million harvest hats per year.[29]

With the rise of the automobile, fashions began to change by the 1930s. In 1931, the company expanded into men's straw dress hats to adopt to evolving fashion trends.[3] In 1938, the company name was changed to International Hat Company to better reflect the growing diversity of its product lines.[3] In 1940, the product lines were further expanded when International Hat began production of military sun helmets for the US military.[10] The war effort led to a realignment of production geared towards military apparel.[10]

With the death of Isaac Apple in 1935, his nephew George Tilles, Jr., was promoted to president of the company. Tilles served as president until his retirement in 1956 and as chairman of the board until his death in 1958.[21] Through the depression of the 1930s, Tilles managed the expansion of the company's facilities from a modest 5,000 square foot factory to a modernized 150,000 square foot factory.[30] Under Tilles, International Hat saw increasing growth during World War II. By 1942, the company's operations had grown to include its main factory facility, several warehouses, two buying offices in Mexico, and a sales office in New York City.[3] The company was also importing goods from a dozen countries.[3]

New markets and expansion

Following World War II, the International Hat Company entered an expansionist period with new markets, facilities, product lines, and basic materials. Frank Pellegrino served as vice president under George Tilles, Jr., becoming president of International Hat from 1956 until 1971 and chairman until his death in 1975.[21][31] Tilles placed Pellegrino in charge of opening a second factory.[13] In 1946, a new facility was constructed and operational in Oran, Missouri, becoming the largest employer in the city.[32]

Pellegrino managed International Hat into a company of over 1,500 employees with six domestic factories. During the 1950s and 1960s, International Hat expanded from its factory in St. Louis to include five other factories located in Southeast Missouri. A number of these locations became one factory towns. Additionally, a sixth plant was opened in Texas.[15] Reflecting this period of expansion into foreign markets, the company headquarters was also moved from St. Louis to New York City.[15] During this era, the company continued producing military helmets and straw hats. However, the company expanded its products lines into plastic hats and helmets, as an early entrant into this new consumer market. As press fiber waned, plastic allowed for more automated production and lighter materials, without the ventilation issues of pressed fiber trapping heat. Throughout the 1960s, the company began shifting into the baseball cap market.[11] In 1967, International Hat began its first consumer focused advertising campaign, to expand its reach in the retail sector, with advertising agency Stemmler, Bartram, Fisher & Payne.[33] In the 1970s, the company expanded into the winter apparel market, selling earmuffs manufactured by VIP Industries.[34]

Under Pellegrino, this would later prove as the height of the expansion of the company in terms of size, productivity, and financial success.[35]

Sale, decline, and liquidation

Jean S. Goodson became president of International Hat in 1971, following Pellegrino's retirement.[31] That same year Pellegrino was elected chairman of the board, which he retained until his death in 1975. Goodson began cutting down on the company's imports from the New York office and limiting the production of dress hats to focus on other product lines.[35] Unsatisfied with his performance, the board of directors requested Frank G. Pellegrino, Sr., minority shareholder and son of Frank P. Pellegrino, represent International Hat in pursuing the sale of the company.[36] At that time, Pellegrino was president of General Moulding Company, a subsidiary of International Hat, in the production of plastic molds for the parent company's hats and helmets. In 1977, Pellegrino initiated the sale of the company to Interco, Incorporated, a conglomerate of furniture, apparel, and shoe companies (now known as Furniture Brands International). On March 31, 1978, a special meeting of the stockholders was held to consider the terms by which Interco offered International Hat.[35] The stockholders accepted the deal and International Hat was officially sold to Interco by the end of the day.[15] The original shareholders were bought out and Jean Goodson continued on as a member of the Interco board of directors from 1978 until his retirement in 1985.[15][37] The company was purchased for 166,667 shares of Interco common stock.[38]

As a subsidiary, International Hat continued operation until June 14, 1989.[39][40] The domestic hat apparel market had undergone a steady increase in global competition since the 1970s during a time of record sales of hats in the US.[41] The company was pressured by changing market conditions, particularly the US loss of market share from cheaper imports coming in from Brazil, Spain, Taiwan, and China.[42] In 1984, China alone exported 2.98 million dozens of hats to the United States.[5] By 1989, 6.5 million dozens of hats were being imported from China, representing 31 percent of the total market share of the hat apparel industry.[5] Demand for hats actually increased during this period, whereas the US market share of hats decreased from 27.1 percent to 22.2 percent from 1984 to 1989.[5]

However, the mortal blow to the company derived from Interco's response to a hostile takeover bid. In 1988, Steven and Mitchell Rales, of the Cardinal Acquisition Corporation, offered $2.5 billion for the company.[43] In response to the offer, Interco's board authorized $1.95 billion in additional debt to buyback stock.[16] Senior management hired Goldman, Sachs & Company to restructure the company, including a plan to sell 16 of Interco's 20 companies.[44][45] While this restructuring plan successfully avoided the hostile takeover, the company was unable to support its debt payments in the subsequent years.[46] From 1989 to 1991, Interco was forced to divest the totality of its shoe and apparel divisions in an attempt to remain solvent.[47] While the majority of these wholly owned subsidiaries were profitable before their liquidation, the full value of these assets was never realized by Interco, as the parent company struggled to pay off its debts raised primarily through the acquisition of junk bonds.[48] The combination of selling the majority of its companies, while being saddled by over $2 billion in debt, created unsustainable negative cash flow, resulting in Inteco's bankruptcy in 1991.[46] Thus in spite of being a profitable subsidiary, International Hat was liquidated in 1989 in a fire sale to Paramount Cap Company.[5]

Successors

The factories in Dexter, Marble Hill, and Oran were re-opened in May 1989, after being sold in the liquidation to Paramount Cap Company.[5][17] The Dexter plant was shuttered in 2000 before being sold to Venture Products, Inc. and re-opened in 2001.[49] The factory in Oran was sold to Carr Textile Corporation, which was subsequently sold to Venture Products, Inc.[50] At present, the Oran hat plant is operational in the production of straw hats.

Products

International Hat produced a variety of products over eighty-three years of operations. However, it is most well known for its production of several different models of fiber pressed military sun helmets provided to the US armed services during World War II. From World War II to the Gulf War, the pressed fiber sun helmet is noted for the historic length of its military usage in the United States, outlasting the M1 steel helmet by approximately ten years.[52] This makes the pressed fiber sun helmet one of the longest used helmets in service by the United States military.[52] Throughout World War II, International Hat was one of two major government contracted manufacturers of the pressed fiber sun helmets for US military personnel.[53][52] Hawley Products Company was the other major government contractor.[53][54] Between Hawley Products Company and International Hat Company, over 100,000 sun helmets were produced for military use in the European and Pacific theaters.[51]

The United States Marine Corps used the International Hat sun helmet both as combat gear and as part of the Marine Corps training uniform.[53][55] The pith helmet, nicknamed the "elephant hat", was first issued to the 1st Marine Division for its 1941 deployment to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The pith helmet has been retained as the mark of the marksmanship range coach.[56]

Although the International Hat sun helmet was designed and introduced before the M1 steel helmet, the International Hat sun helmet continued to be used in the military for many decades, including the Korean War and Vietnam War.[53][52] By the Gulf War, only certain personnel in the US Navy had the pressed fiber sun helmet as serviceable gear.[53]

Military logistics records preserve the stock number, product type, military service date, and quantity produced for military use. Each service branch of the military kept separate quartermaster records until 1947. In particular, the US Army is known to have commissioned 38,423 International Hat helmets for World War II and its aftermath.[10]

| Product Stock Number | Type of Product | Order Received Date | Quantity Sold By Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army W-699 | Fiber Military Helmet | February 10, 1942 | 15,878[10] |

| Army PO | Fiber Military Helmet | May 1942 | 10,989[10] |

| Army W-30 | Fiber Military Helmet | 1946 | 11,875[10] |

Legal issues

International Hat has had several labor issues settled in the US legal system. The company also participated in ways to avoid legal issues. In 1934, Frank P. Pellegrino represented the company in Washington, D.C., at the US Hat Manufacturing Code hearing, to update manufacturing and labor practices within the industry, as the industry attempted to mitigate the need for government regulation during the New Deal era. International Hat's labor issues were generally with the National Labor Relations Board and the issue of unionization. Over the decades, the employees of the company never unionized, although unsuccessful attempts at unionization were made in joining the United Hatters, Cap, and Millinery Workers International, an AFL–CIO affiliate of 20,000 hat workers.[25][57]

Unionization never proved popular with the employees or the culture of the company.[57] In 1976, the Oran factory voted to unionize with the Retail Clerks Union but the motion failed.[58] In 1985, the National Labor Relations Board ruled against International Hat Company for allegedly violating elements of the National Labor Relations Act.[57] The company was claimed to have infringed upon the right of Tex Barnes, a cutter at the International Hat factory in Piedmont, Missouri to organize a union.[57] Barnes led the efforts for certification in April 1980 and was also a member the union's negotiating committee.[57] However, as in previous instances, the union lost the election when put to an employee vote.[57] The union was formally decertified on March 4, 1982.[57] Barnes filed an unfair labor practice charge against the company nine months later.[57] Although the National Labor Relations Board ruled in Barnes' favor, the United States Court of Appeals Eighth Circuit vacated and remanded the earlier decision.[57]

Philanthropy

International Hat engaged in various philanthropic activities. Most notably, was the establishment of two municipal parks under President and Chairman Pellegrino. Following the death of his business associate and the former president, Pellegrino donated land and money for the construction of a municipal park in Oran, the George Tilles Jr. Memorial Park.[32] In 1968, Pellegrino commissioned a new park in Marble Hill, MO.[59] Maria Pellegrino Park was dedicated in memory of Pellegrino's mother and opened to the public on June 2, 1972.[60] During the dedication ceremonies, the Mayor declared the event to be remembered as "Pellegrino Appreciation Day."[61] International Hat directly donated money to building the large pavilion at Pellegrino Park.[60]

Another philanthropic activity of the company was the donation of hats to certain American volunteer organizations. In 1981, International Hat donated 4,764 hats to the national convention of the Girls Scouts of America.[62] In 1989, the company produced 200 specially made women's spring hats for the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GWFC) convention delegates in Marble Hill.[63]

Legacy

In the subsequent decades of World War II, International Hat military fiber sun helmets, produced at the original factory in St. Louis, have become collector's items for military helmet and World War II collectors of American military uniform apparel. This is particularly true of the International Hat Marine helmets, which bear the USMC insignia on the front of the helmet.[53]

Facilities

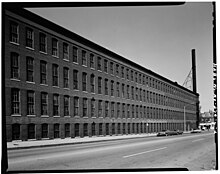

International Hat had multiple domestic and international facilities. At the height of its expansion, International Hat operated seven domestic factories, several warehouses, several international buying offices, and a sales office in New York.[3] Among all its facilities, the International Hat Company warehouse in the Soulard neighborhood of St. Louis is of particular historic note. On October 20, 1980, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[1] Built in 1904, by renowned architect Albert B. Groves, the building was originally a factory for the Brown Shoe Company.[1] In 1954, the factory was subsequently converted into a warehouse by the International Hat Company, which owned and operated the site until 1976.[1] The site has been recognized as a testament to Grove's architectural expertise in early 20th century industrial design.

In 1917, the original International Hat headquarters was located at 711 Lucas Avenue.[6] From 1917 to 1928, the factory manufactured straw harvest hats.[6] By the 1920s, the company was the largest manufacturer of harvest hats in the world from this facility.[6] In 1928, the company purchased 2528 Texas Avenue from Koken Barbers' Supply Company and sold the original factory at 711 Lucas to Koken as part of the deal.[6] The Texas location would continue manufacturing straw harvest hats, as well as all military sun helmets produced during and after World War II.[3] This five-story building included 87,000 square feet, or approximately two acres.[64][65] In 2016, this facility was purchased by two non-profit organizations, DeSales Community Development and St. Louis Makes to form a new joint private non-profit organization called Brick City Makes.[66][67] The Brick City Makes hub is noted as being the first non-profit organization in the United States to renovate an industrial building in order to provide rent space and development, as a business incubator, for entrepreneurial manufacturers.[65][66] The Brick City Makes business incubator, at the former International Hat factory, is the first model in the US to focus on business support services that grow the expertise and profitability of manufacturers and inventors until their organizations are large enough to exit the incubator and launch independently elsewhere.[66][68]

Six factories were located in Missouri and the seventh operated in Texas. The majority of warehouses were located with the factories onsite. From 1928 to the 1960s, the largest International Hat factory also served as the headquarters of the company, which was located in St. Louis, Missouri.[6] The other factories in Missouri were located in Chaffee, Dexter, Marble Hill, Piedmont, and Oran.[11][69][70] The Oran factory was constructed in 1946.[71] The factory was expanded in 1948 and 1968.[72] It eventually closed in 1984.[73] The Chaffee plant was closed in 1981 after opening in the summer of 1980 with 100 employees.[74][75][76] The Chaffee factory was operated by Florsheim Shoe Company, another subsidiary of Interco.[77] The Marble Hill factory was expanded in 1972.[78] The facility employed approximately 300 workers.[79] The Dexter facility was opened in 1959 and operated for 30 years under International Hat, eventually closing permanently in 1989.[5]

Presidents

- Isaac Apple (1917–1935)[80]

- George Tilles, Jr. (1935–1956)[81]

- Frank P. Pellegrino (1956–1971)[31]

- Jean S. Goodson (1971–1978)[31][37]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fox 1995, p. 54.

- ^ a b National Register of Historic Places, Nomination Form. Missouri State Government. December 1975. Retrieved on March 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k International Hat Company 1942, p. 3.

- ^ a b "President of Hat Company Accused General Manager of Embezzlement". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. August 14, 1918. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "New Ownership Gives Life Back to Factories". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, MO. April 19, 1989. p. 1. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Harvest Hat Company Buys Five-Story Building". St. Louis Star and Times. St. Louis. August 16, 1928. p. 17.

- ^ "Building Boom Gains Momentum". Southeast Missourian. May 19, 1972. p. 2. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Marble Hill to Ballot on Gift of Cash, Park". Southeast Missourian. May 17, 1969. p. 3. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Hat Department". The Clothier and Furnisher. 95 (1): 193. 1919. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lemons 2011, p. 212.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Stephen (June 5, 1971). "Oran, Village of Distinctive Personality, Self-Sufficient". Southeast Missourian. p. 1. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "Plant Closing is a Blow for Bollinger County". Southeast Missourian. March 26, 1989. p. 10A. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ a b "$10,000 Gift, Voter Approval Bring City Park". Southeast Missourian. April 2, 1962. p. 1. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Interco Purchases International Hat". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. April 3, 1978. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e "International Hat Company Sold to Interco". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. Associated Press. April 1, 1978. p. 1E.

- ^ a b Water, Judith Vande (April 11, 1988). "Interco Lists $5.9 Million Loss". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. p. 30.

- ^ a b "Dexter Group Buys Area for Industrial Use". Southeast Missourian. July 15, 2001. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ National Register of Historical Places (2016) Brown Shoe Company's Homes-Take Factory United States Federal Park Services. Retrieved March 15, 2016

- ^ "Growing Hat Company Enlarges Its Plant". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. January 9, 1921. p. 57.

- ^ a b "Funeral of Isaac Apple President of Hat Company". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. December 30, 1935. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d International Hat Company 1942, p. 6.

- ^ "Incorporations". St. Louis Star and Times. St. Louis. August 14, 1914. p. 9.

- ^ a b "Embezzlement Charges Against Hat Official". St. Louis Star and Times. St. Louis. August 14, 1918. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Brasch, Phyllis (October 6, 1980). "St. Louis' Hat and Cap Industry: Nearly 100 Years of Boom, Bust". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. p. 17.

- ^ a b Block, Michael (February 2, 1983). "Hat Industry Puts High Hopes on Your Head". Milwaukee Journal. Hartford Courant. p. 17.

- ^ United States Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1915). Commerce Reports. Washington, D.C. p. 595. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

35 million hats produced in 1910.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Frum, David (December 24, 2014). "The Real Story of How America Became an Economic Superpower". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ^ "Funeral Services Held for Leon M. Shlenker". St. Louis Star and Times. St. Louis. September 29, 1930. p. 3.

- ^ "Harvest Hat Concern Buys 5-Story Factory Building". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 12, 1928. p. 63. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ International Hat Company 1942, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d "International Hat Company Elects J. S. Goodson". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. November 10, 1971. p. 69.

- ^ a b "Oran Gets Factory". Southeast Missourian. November 9, 1946. p. 5. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "St. Louis Advertising and PR Agencies". St. Louis Media History. St. Louis Media History Foundation. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Spradling to Speak at Open House". Southeast Missourian. August 22, 1973. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c Goodson 1978, p. 1.

- ^ Goodson 1978, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Jean S. Goodson: Hat Company President". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. October 26, 2003. p. 9.

- ^ "Interco Acquiring International Hat". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. January 10, 1978. p. 58.

- ^ "Last International Hat Plant to Close". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. March 29, 1989. p. 27.

- ^ "Interco to Close Hat Plant, Idling About 200 in Southeast Missouri". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Associated Press. March 23, 1989. p. 49.

- ^ Norris, Floyd (September 19, 1979). "Record Sales of Hats". Herald-Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, p. 71.

- ^ Vise, David A.; Coll, Steve (August 26, 1988). "The Rales Brothers Play For Big Stakes". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Cardinal Extends Takeover Offer for Interco". Baltimore Sun. Associated Press. September 12, 1988. p. 23.

- ^ Michael Quint. "Market Place; A Takeover Bid Revives Interco" New York, NY: New York Times, August 22, 1988. Retrieved on March 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Manor, Robert (February 27, 1991). "Judge Rejects Interco Financing Agreement". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. p. 19.

- ^ Schmidt 1990, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Steyer, Robert; Manor, Robert (January 26, 1991). "Interco Enters Bankruptcy Company Struggling With Heavy Debt Load". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. p. 44.

- ^ "Marble Hill Plant to Close in June; 200 Jobs are Lost". Southeast Missourian. March 22, 1989. p. 1. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Jeffrey (October 27, 1997). "Venture Products to Expand, Consolidate". Southeast Missourian. p. 10B. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Suciu, Peter (December 4, 2015). "The American Pressed Fiber Helmets Blueprints". Military Sun Helmets. Military Helmet Experts. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Suciu & Bates 2009, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f Suciu, Peter (June 22, 2012). "USMC Pressed Fiber Helmet – Training Helmet and More". Military Sun Helmets. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ^ Lemons 2011, p. 195.

- ^ Suciu & Bates 2009, p. 58.

- ^ Wharton, Abigail M. (September 9, 2010). "Marine Corps Installations Pacific". United States Marine Corps. United States Government. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McMillian, Judge; Henley, Judge; Fagg, Judge. "INTERNATIONAL HAT COMPANY, Petitioner, v. NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS BOARD, Respondent". Legal Resource. United States Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Firm to Vote on Union". Southeast Missourian. August 16, 1976. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Twin Cities Get Offer of Land, Cash for Park". Southeast Missourian. April 2, 1969. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "Dedicate New Bollinger Park". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, MO. June 5, 1972. p. 12. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Dedicate New Park at Ceremonies Sunday". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau, MO. June 2, 1972. p. 3. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Hats for Scouts". Southeast Missourian. September 10, 1981. p. 3. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Spring GWFC Draws 126 Delegates". Southeast Missourian. May 9, 1989. p. 12. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Hub For Small, Growing Manufacturers Planned for 87K SF Fox Park Warehouse". Next St. Louis. January 11, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Barker, Jacob (January 11, 2017). "New Shared Space for Young Manufacturers Planned in Fox Park". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c Feldt, Brian (January 11, 2017). "New workspace planned for Fox Park industrial building". St. Louis Business Journal. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ "Hub for Growing Manufacturers Planned for Fox Park Warehouse". Construction for St. Louis. January 14, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ Moffitt, Kelly. "Old, Industrial Building in South St. Louis to Transform into Manufacturing Hub, Community space". St. Louis Public Radio. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ Owen, Ray (March 29, 1989). "Factory Job Loss Passes 900". Southeast Missourian. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "City Honors Industry". Bulletin Journal. August 7, 1980. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Oran to Plan Factory Drive". Southeast Missourian. October 3, 1947. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Business & Commerce Cape Girardeau". Southeast Missourian. November 16, 1968. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Factory Closings". Southeast Missourian. March 29, 1989. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Out of the Past: April 17, 1980". Southeast Missourian. April 17, 2005. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Chaffee Named as Plant Site". Southeast Missourian. June 22, 1983. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "New Plant". Southeast Missourian. May 9, 1980. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Chaffee". Southeast Missourian. June 11, 1984. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ "Began Building Addition on Marble Hill Hat Company Soon". Southeast Missourian. February 25, 1972. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Gas leaks cause minor discomfort". Southeast Missourian. January 7, 1980. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Funeral Is Held for Hat Firm Head, Isaac Apple". St. Louis Star and Times. St. Louis. December 30, 1935. p. 22.

- ^ "George Tilles Jr. Dies; Hat Firm's Board Head". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis. October 27, 1958. p. 24.

Bibliography

- Fox, Tim (1995). Where We Live: A Guide to St. Louis Communities. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Historical Society Press. p. 54. ISBN 188398212X. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

International Hat Company warehouse St. Louis.

- Goodson, Jean S. (March 2, 1978). "Notice of Special Meeting of Stockholders: Proxy Statement". International Hat Company.

- International Hat Company (1942). International Harvest Hat Company: A Brief History, 1917–1942 (25th Anniversary ed.). St. Louis, MO.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lemons, Charles R. (2011). Uniforms of the US Army Ground Forces (1939–1945), Addendum. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Press. ISBN 978-1105268922. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Schmidt, Richard John (1990). The Divestiture Option: A Guide for Financial and Corporate Planning Executives. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0899303978. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Suciu, Peter; Bates, Stuart (2009). Military Sun Helmets of the World (1st ed.). Uckfield, UK: Naval and Military Press. ISBN 9781894581523.

Further reading

- Army Service Forces, Headquarters (1943). Quartermaster Supply Catalog QM 3-2. Washington D.C.: United States Armed Forces. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- Carver, Nancy Ellen (2002). Talk with Tilles: Selling Life in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris[self-published source] Publishing. ISBN 1401071996.

- Kalajian, Perry (1992). "The Controversial World of Corporate Mergers and Acquisitions: A Critical Assessment". Missouri Law. 57 (3): 745–832. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Tulkoff, Alec (2003). Grunt Gear: USMC Combat Infantry Equipment of World War II. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 0912138920.

- United States Congressional Serial Set. United States Government Printing Office. 1913. pp. 4, 987–5, 009. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

External links

- "Evolution of the American Pressed Fiber Helmet," by military helmet experts Peter Suciu and Stuart Bates.

- Harvest Hat Patent

- Former International Hat Building. National Register of Historical Places.