Contents

Liberty is a town in DeKalb County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 367 at the 2000 census and 310 in 2010. Liberty's main street was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 as the Liberty Historic District.[6]

History

Liberty was settled circa 1797 by Adam Dale, an American Revolutionary War veteran from Maryland who built a mill on Smith Fork Creek.[7]

Much of Main Street in Liberty is included in an historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Properties in the historic district include the Liberty High School, built from limestone quarried in the area, and the Salem Baptist Church and cemetery.[8]

On the evening of March 23, 1889, Liberty was hit by a tornado that uprooted trees and caused extensive damage to homes. A local church was completely destroyed. According to records, there were no fatalities reported.[9]

Geography

Liberty is located at 36°0′18″N 85°58′22″W / 36.00500°N 85.97278°W (36.004959, -85.972816).[10]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 1.0 square mile (2.6 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 285 | — | |

| 1950 | 314 | — | |

| 1960 | 293 | −6.7% | |

| 1970 | 332 | 13.3% | |

| 1980 | 365 | 9.9% | |

| 1990 | 391 | 7.1% | |

| 2000 | 367 | −6.1% | |

| 2010 | 310 | −15.5% | |

| 2020 | 334 | 7.7% | |

| Sources:[11][12][3] | |||

At the time of the 2000 census[4] there were 367 people, 160 households, and 112 families residing in the town. The population density was 354.5 inhabitants per square mile (136.9/km2). There were 181 housing units at an average density of 174.8 per square mile (67.5/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.28% White, 1.36% African American, 0.54% Asian, 0.54% from other races, and 0.27% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.82% of the population.

There were 160 households, out of which 31.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.1% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.4% were non-families. 27.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.70.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 22.1% under the age of 18, 6.5% from 18 to 24, 29.7% from 25 to 44, 31.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.6 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $36,806, and the median income for a family was $42,031. Males had a median income of $27,750 versus $19,125 for females. The per capita income for the town was $19,856. About 17.8% of families and 25.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 52.1% of those under age 18 and 20.0% of those age 65 or over.

Government

The town of Liberty is governed by a mayor and a board of aldermen, consisting of five members. Both the mayor and aldermen are elected by the citizenry in at-large elections.[13]

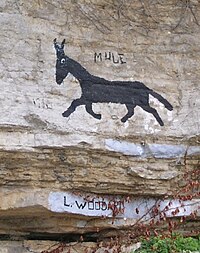

Allen Bluff Mule

The "Allen Bluff Mule" is a painting of a mule on a limestone bluff on U.S. Route 70 in Liberty. Some residents say a local man named Lavader Woodard painted the mule; other residents contend that it was painted as an advertisement of a local stock farm. Dr. Wayne T. Robinson has claimed to be the original painter of the Liberty Mule:

In early October 1906, I climbed up the face of the Allen Bluff to a ledge and with some coal tar made a flat picture of a character from a famous comic strip of that day. Everybody remembers Maud, the mule. That was 51 years ago, and even though it has been exposed to the elements and to nearby earth-shaking explosions, erosion has dimmed it very little. On the same bluff is the name of Will T. Hale, which was inscribed about 85 years ago.[14]

By this account, Dr. Robinson painted the original mule while a 21-year-old college student inspired by Maud the Mule, from the Frederick Burr Opper comic strip And Her Name Was Maud.

In 2003, Liberty residents became upset that an expansion of U.S. 70 to a four-lane road could threaten the mule painting. The residents started a letter writing campaign to the Tennessee Department of Transportation. Supporters of the mule also placed signs along the roadway stating "Save the Mule." Ultimately the road expansion was far enough away from the mule, that it was never in any danger.

Notable people

- Bob Griffith, baseball player

- Justin Potter (a.k.a. "Jet" Potter) (1898–1961) [15][16]

References

- ^ Tennessee Blue Book, 2005-2006, pp. 618-625.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Liberty, Smithville-DeKalb County Chamber of Commerce website, accessed January 18, 2010

- ^ Liberty, Center Hill Realty website, accessed January 18, 2010

- ^ [1], Gendisasters website, accessed June 28, 2010

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ City of Liberty, Smithville-DeKalb County Chamber of Commerce website, accessed January 18, 2010

- ^ "Historian unravels Liberty Mule mystery" by Thomas G. Webb, DeKalb County Historian, The Smithville Review November 11, 2006.

- ^ Associated Press, Tennessee Millionaire, Justin Potter, Dead, The Tuscaloosa News, December 10, 1961

- ^ Heinz Dietrich Fischer, Erika J. Fischer, National Reporting, 1941–1986: From Labor Conflicts to the Challenger Disaster, Walter de Gruyter, 1988, Volume 2, pp. 145-146 [2]