Contents

The Scribner Building (also known as the Old Scribner Building) is a commercial structure at 155 Fifth Avenue, near 21st Street, in the Flatiron District of Manhattan in New York City. Designed by Ernest Flagg in the Beaux Arts style, it was completed in 1893 as the corporate headquarters of Charles Scribner's Sons publishing company.

The Fifth Avenue facade contains a base of rusticated limestone blocks on its lowest two stories. On the third through fifth stories, the facade is subdivided into five limestone bays, while at the sixth story is a mansard roof. Among the facade's details are vertical piers at the center of the facade. At ground level is a retail space that was originally used as Scribner's bookstore. The upper stories originally contained the offices of Charles Scribner's Sons and were subsequently converted into standard office space.

Charles Scribner's Sons was founded in 1846 as Baker & Scribner, which occupied several buildings before moving to 155 Fifth Avenue. The company used the Old Scribner Building until 1913, when the firm moved to 597 Fifth Avenue, a structure also designed by Flagg. The family continued to hold the building until 1951, leasing it as office space. The Old Scribner Building was used as the headquarters of the United Synagogue of America from 1973 to 2007. The building was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) in 1976 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1980. It is a contributing property to the Ladies' Mile Historic District, which was designated by the LPC in 1989.

Site

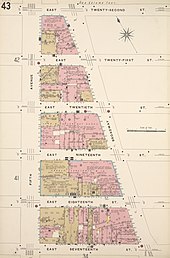

The Old Scribner Building is at 155 Fifth Avenue in the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City,[2] on the eastern side of the avenue between 22nd Street to the north and 21st Street to the south.[3] The building spans the addresses 153–157 Fifth Avenue.[2] The trapezoidal land lot covers 4,825 square feet (448.3 m2), with a frontage of 59.25 feet (18.06 m) on Fifth Avenue and a depth of 87.58 feet (26.69 m). Nearby buildings include the Flatiron Building and 935–939 Broadway to the north, as well as the Sohmer Piano Building to the west.[3][4]

The surrounding stretch of Fifth Avenue was developed with residences in the 1840s, which were demolished to make way for commercial and office uses by the late 19th century. The Scribner Building is one of several late-19th century office structures developed in the neighborhood.[5] Just prior to the Old Scribner Building's construction, the lots at 153–155 Fifth Avenue may have been occupied by the Glenham Hotel.[6] However, city records show that the hotel could have been on the adjoining lot to the south.[7]

Architecture

The Old Scribner Building was designed by Ernest Flagg in the Beaux Arts style for the company Charles Scribner's Sons.[2][8] It has a gross floor area of 37,288 square feet (3,464.2 m2).[3] The building is similar in appearance to the successor Scribner's bookstore at 597 Fifth Avenue, which Flagg also designed. Both structures have symmetrical limestone facades divided horizontally into multiple sections.[9] The Old Scribner Building's superstructure consists of a steel frame with brick infill.[10][11] The main contractor was Charles T. Wills.[11]

Upon the completion of the building, Scribner's Magazine said its headquarters had a "dignified and striking facade".[12] According to Scribner's Magazine, the building was "the first in America built from ground to top distinctly for the uses of a publishing house".[13][14] The design was praised by the architectural critic Francis Swales as being "one of the earliest" small stores in New York City to "possess any architectural merit".[15][16]

Facade

The facade is horizontally separated into three sections—the ground-story base, the second through fifth stories, and the sixth-story roof—each subdivided into five vertical bays.[13][17] The facade uses rusticated blocks of limestone at the base, contrasted with plain limestone on the upper stories, to resemble a load-bearing wall.[10] The ground or first story was designed with large central openings flanked by smaller doorways.[16] It is clad with rusticated limestone blocks and has an arched glass-and-iron storefront in the three center bays.[13][17] The arch was intended to give the impression of a truss supporting the stories above.[16] Above the center of the first floor is a cartouche with the capital letters "Charles Scribner's Sons", above a garland flanked by putti. There are rectangular doorways on either side of the storefront. Above each doorway is an entablature as well as cornice supported on brackets.[13][17] Originally, a curved glass marquee projected from the storefront.[16][17][18]

The windows on the second through fifth stories are the same size as each other.[16] The second story is clad with rusticated limestone blocks, similarly to the first story, with a stone band course at the top. The three center windows are designed as tripartite openings with two small colonettes, one on each side. Above the central second-story window are brackets shaped like lions' heads, which support a slightly protruding balcony at the central third-story window.[17][19] The third and fourth stories are treated as a single large opening.[16] At these stories, the three center bays are separated by vertical pilasters and flanked by half-pilasters. The inner bays are slightly recessed behind the pilasters, with carved iron spandrels separating the windows between either story. The outer bays are slightly projected from the inner bays and are more simple in design, with cornices above the third-story outer windows. An entablature with a pellet molding runs atop the fourth story. At the fifth floor, the three center windows are all tripartite openings with colonettes, while the two outer windows each contain one pane and are flanked by broad pilasters.[17][19] The fifth story is designed to appear like a deep frieze.[16]

A cornice with closely spaced console brackets runs above the fifth story, topped by a parapet and a slate mansard roof.[20][21] At the sixth story, the outermost bays have curved broken pediments containing cartouches, below which are inscriptions with dates in Roman numerals. The inscription above the left bay is MDCCCXLVI (1846), the date when Scribner's was founded as Baker & Scribner, while the inscription above the right bay is MDCCCXCIII (1893), the date of the Old Scribner Building's completion.[22] In the center bay above the cornice is a double-height dormer that projects from the roof. This dormer contains a tripartite window, with a horizontal transom bar near the top, and is topped by a pediment containing a cartouche. There are skylight windows in the roof on either side of the dormer.[20][22]

Interior

The retail space on the ground story was originally the Scribner's bookstore.[22][14] Upon the building's completion, the bookstore was described in Scribner's Magazine as resembling a "particularly well-cared-for library in some great private house, or in some of the quieter public institutions".[14][23] The ground-story walls were clad in oak, and full-height bookcases with glass shelves were placed in front of each wall.[14][24] These glass shelves were custom-made in France and were used because they were more clean-looking and sturdier than wood.[25] The center of the room had oak tables with book displays.[14] The wooden floor was laid on asphalt blocks and the ceiling was supported by high columns with Corinthian-style capitals. There was also a marble staircase at the rear of the store, with decorative iron railings containing "C" and "S" motifs.[14][26] The stair led to a gallery that surrounded the room on all sides except the west.[26] Also at the rear of the store, but at ground level, was a set of offices.[14] The building retained its retail use after Scribner's moved out during 1913.[26]

Two stairs led from the gallery to the second floor, one on either side of the stair from ground to gallery.[14] Additional office entrances are in the side bays of the facade.[26] The second floor originally contained Scribner's operating departments, such as the financial and manufacturing, wholesale, educational, and book-buyers' departments. The third floor was occupied by the departments of Scribner's Magazine such as the editorial, artistic, and publishing departments. The fourth floor contained the subscription department, while the fifth floor had storerooms. The sixth story included mail rooms, circular-printing equipment, as well as what Scribner's Magazine called "the other miscellany of a great business".[14]

History

In 1846, Charles Scribner I and Isaac D. Baker formed publishing company Baker & Scribner, which Scribner renamed the "Charles Scribner Company" after Baker's death in 1857.[2][27] The company was headquartered at several buildings in Lower Manhattan through the mid-19th century.[27][28] The name of the company was changed to Charles Scribner's Sons in 1878.[2][29] In subsequent years, the company published works such as Scribner's Magazine, Baedeker Guides, the Dictionary of American Biography. In addition, Charles Scribner's Sons published books for various authors.[2] The Glenham Hotel opened on September 17, 1869.[30]

Scribner's usage

In October 1893, Charles Scribner's Sons were reported as the buyers of the Glenham Hotel at 153 and 155 Fifth Avenue in the Flatiron District.[6][31] Charles Scribner II, the head of Charles Scribner's Sons during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hired his brother-in-law Ernest Flagg to design the new building.[31][32] Plans were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings that December.[33] The Scribner's bookstore relocated to the new building from its previous location on 745 Broadway during May 1894.[34][35] Over 300,000 books, manuscripts, letters, and accounts were moved within one month; according to The New York Times, "not one was even imperceptibly damaged".[34] The project cost $150,000 (equivalent to $4,727,000 in 2023).[11] That December, Scribner transferred the leasehold to the Union Trust Company.[36]

Upon the building's completion, a New York Times reporter described the bookstore as having a wide collection of items, including rare volumes and documents. The space was described as having the "appearance of a large public library", with a skylight in the rear illuminating the whole store.[37] Additionally, the Scribner Building hosted several events and exhibitions. For instance, in November 1894, the building had a bookbinding exhibition "under the gracefully-shaped architectural marquise of which it is delightful to pass in", as it was described by The New York Times.[38] The following year, the bookstore displayed some Robert Louis Stevenson memorabilia.[39] These events continued through the first decade of the 20th century. In 1908, the store exhibited a series of rare documents, books, manuscripts, and autographs, including several centuries of papal and French royal documents.[40][41]

By the beginning of the 20th century, development was centered on Fifth Avenue north of 34th Street.[42][43] Scribner's was among the companies that decided to relocate further north in Manhattan.[44] By January 1911, Ernest Flagg had written in his diary that Charles Scribner II had discussed the possibility of constructing a new quarters along Fifth Avenue.[23] The new structure at 597 Fifth Avenue, near 48th Street, opened by May 18, 1913,[45][46] thus becoming the seventh headquarters of Charles Scribner's Sons.[47] The development of the 597 Fifth Avenue building was described by architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern as "sure testimony to the rapid march of commerce to upper Fifth Avenue".[48]

Other occupancy

Following their relocation, Charles Scribner's Sons continued to hold the old building, leasing it in October 1913 to glass importers D. Bloch & Company.[49] D. Bloch moved to the building soon afterward, in what local media described as one of several signs of the surrounding neighborhood's mercantile redevelopment.[50][51] In 1920, some space was leased to Bardival Brothers, a lace and embroidery merchant.[52]

In 1934, the 153 Fifth Avenue Corporation leased the building for twenty-one years. The company was to refurbish the building for $40,000, adding retail on the first story and lofts on the other stories.[53][54] The renovations were designed by the Scribners' architect Louis E. Jallade along with the tenants' architect Arthur Weiser.[54] Among the modifications were the installation of new storefront windows.[20] Brown, Wheelock, Harris & Co. were named as the leasing agents for 153 Fifth Avenue's office space the same year.[55] Some space was taken by Alliance Distributors,[56] which renovated its offices on the third and fourth floors in 1937 to plans by F. P. Platt & Brother.[57][58] Blond wood barriers were installed at the ground floor, just inside the entrance, sometime in the 1940s or 1950s.[26] The Scribner family continued to own the building until 1951.[31] The following December, the building was transferred from the 153 Fifth Avenue Corporation to Harry C. Kaufman.[59]

The storefront was renovated in 1969, upon which the storefront's glass marquee was removed.[17] The United Synagogue of America (later United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism), an alliance of Conservative Jewish synagogues, acquired the building in 1973.[31][60] The Old Scribner Building became the United Synagogue's headquarters and was named Rapaport House.[61] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Old Scribner Building as a city landmark on September 15, 1976,[2][60] and the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 6, 1980.[1] The LPC further designated the Old Scribner Building as part of the Ladies' Mile Historic District,[62] a city landmark district created in 1989.[63] There were few vestiges of the Scribner company remaining on the facade by the 1990s.[61]

The United Synagogue sold the building in 2007 for $26.5 million to Philips International Holding.[64][65] The new owner sought to market the space toward a fashion tenant.[64] However, the building was resold the following year to the Eretz Group for $38 million.[66] During the 2010s, tenants of the Old Scribner Building included a showroom and office for clothing designer Rachel Zoe,[67] a store for The White Company,[68][69] and coworking space Knotel.[70][71]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Federal Register: 46 Fed. Reg. 10451 (Feb. 3, 1981)" (PDF). Library of Congress. February 3, 1981. p. 10649 (PDF p. 179). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "153 5 Avenue, 10017". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, pp. 144, 293, 296.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, p. 151.

- ^ a b "In the Real Estate Field; Details of Some Private Sales of Residence Property" (PDF). The New York Times. October 14, 1893. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, p. 144.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1982, p. 5.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 7.

- ^ a b c "Present Condition of Big Building Enterprises". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 53 (1368): 882. June 2, 1894. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Scribner's Magazine 1894, p. 802.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, p. 282.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scribner's Magazine 1894, p. 804.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, pp. 200–201.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Architecture in the United States; IV—The Commercial Buildings—The Shops". The Architectural Review. Vol. 25. January–June 1909. p. 85. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 2; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 201.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, pp. 282–283.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, p. 283.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, pp. 2–3; National Park Service 1980, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 3; National Park Service 1980, p. 3.

- ^ a b Marthey, Lynne D. (July 11, 1989). "Charles Scribner's Sons Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. pp. 5–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 3.

- ^ "Library Furniture and Glass Shelves" (PDF). The New York Times. May 1, 1897. p. BR4. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 1980, p. 3.

- ^ a b Scribner's Magazine 1894, p. 793.

- ^ "Publishers Uptown: Chas, Scribner's Sons and E. P. Dutton & Co. In New Quarters". New-York Tribune. April 26, 1913. p. 11. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Scribner's Magazine 1894, p. 794.

- ^ "A New Hotel on Fifth-Avenue". The New York Times. p. 8. ProQuest 92536513.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1976, p. 2; National Park Service 1980, p. 6.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (October 23, 1994). "Streetscapes/The Charles Scribner House; A Quintessential Flagg Building Is Being Restored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "New Buildings and Alterations". The New York Times. December 8, 1893. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 95082298. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Charles Scribner's Sons' Removal; Not One of at Least 300,000 Books Injured -- Old Building Almost Deserted" (PDF). The New York Times. May 25, 1894. p. 8. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Literary World". The Buffalo Commercial. May 28, 1894. p. 7. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Leasehold Conveyances". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. 54 (1397): 930. December 22, 1894. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Books for One's Friends; Shops That Are Bright and Gay With Beautiful Volumes" (PDF). The New York Times. December 6, 1894. p. 13. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Bookbindings at Scribners'; Magnificent Exhibition of the Best Works of Famous Artisans" (PDF). The New York Times. November 12, 1894. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Some of Stevenson's Work; Exhibition of Pictures of the Author and Samples of His Writings at Scribner's Sons" (PDF). The New York Times. November 13, 1895. p. 16. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Portraits of the Popes.; From Innocent IV, 1243, Down to Present Pontiff in Scribner Exhibit" (PDF). The New York Times. November 29, 1908. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Historic Letters: the Scribner Exhibition of Rare Manuscripts and Books". New-York Tribune. December 2, 1908. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Wist, Ronda (1992). On Fifth Avenue : then and now. New York: Carol Pub. Group. ISBN 978-1-55972-155-4. OCLC 26852090.

- ^ "Catharine Street as Select Shopping Centre Recalled in Lord & Taylor's Coming Removal". The New York Times. November 3, 1912. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1982, p. 2.

- ^ "Scribners in New Home; Publishing Firm Moves to Fifth Avenue and Forty-eighth Street" (PDF). The New York Times. May 18, 1913. p. 37. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ "Scribners' New Home: Publishing House Now Established at 5th Ave. And 48th St". New-York Tribune. May 18, 1913. p. 7. ProQuest 575077558. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Plaques Will Mark 3 Notable Buildings" (PDF). The New York Times. February 14, 1962. p. 31. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 200.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; Row of Harlem Apartments Sold -- Washington Heights Deal -- Downtown Firm Leases Old Scribner Building on Fifth Avenue -- $100,000 Bronx Sale -- Private House Rentals" (PDF). The New York Times. October 10, 1913. p. 17. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Twenty-third Street's Busy Retail Block Destined for Great Wholesale Centre; Rapid Readjustment of Conditions Shown by Decision of Many Downtown Firms to Move Into Old Shopping District -- Important Goelet Improvement -- Changes in Rental Values" (PDF). The New York Times. March 1, 1914. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Remlin, Frank (January 24, 1915). "Realty Tendencies in Chelsea Section District Seems Bound to Become a Great Wholesale Trade Centre". New-York Tribune. pp. 33, 34. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "$500,000 Rental for Old Scribner 5th Avenue Building". New-York Tribune. February 23, 1920. p. 19. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "To Remodel Building.; Lessees Will Improve Six-story Structure on Fifth Avenue" (PDF). The New York Times. January 4, 1934. p. 36. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "5th Avenue Property Taken in Long Lease". New York Herald Tribune. January 4, 1934. p. 38. ProQuest 1114860116. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Managing Agents Named For Midtown Properties: Nine-Story Broadway Offices Assigned to Really Firm". New York Herald Tribune. September 20, 1934. p. 35. ProQuest 1329080720. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Real Estate: Discount Firm Rents Offices In Wall Street Additional Pine St. Space Taken by F. B. Odium; Broadway Units Leased". New York Herald Tribune. December 21, 1934. p. 39. ProQuest 1221558168. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Real Estate Notes" (PDF). The New York Times. September 30, 1937. p. 41. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Alliance Distributors Expand". New York Herald Tribune. September 30, 1937. p. 44. ProQuest 1240441708. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Manhattan Transfers". The New York Times. December 24, 1952. p. 28. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 112306695. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b Miele, Al (September 15, 1976). "Statue of Liberty a City Landmark". New York Daily News. p. 294. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b Curcio, Barbara (November 7, 1993). "Edith Wharton's New York: Gilt and Innocence". The Washington Post. p. E1. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 140796542. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 1, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1989, p. 281.

- ^ "Ladies' Mile District Wins Landmark Status". The New York Times. May 7, 1989. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "155 Fifth Avenue". The Real Deal. May 22, 2007. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "USCJ Sells Manhattan Headquarters To Stem Red Ink". The Forward. January 21, 2015. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "155 Fifth Avenue". The Real Deal. January 21, 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Designer Rachel Zoe Opening Flatiron District Showroom and Office". Commercial Observer. October 27, 2015. Archived from the original on October 28, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Paton, Elizabeth (June 12, 2017). "A British Home Empire Aims to Colonize America". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Sutherl, Emily (July 5, 2017). "Q&A: The White Company takes on New York". Drapers. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Benowitz, Shayne; Rizzi, Nicholas; Gourarie, Chava (October 5, 2018). "Knotel Inks Three Manhattan Lease as WeWork Gets Into 'HQ' Business". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Noto, Anthony (October 24, 2018). "Knotel closes $60 million in funds, eyes NYC expansion". New York Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

Sources

- "The History of a Publishing House, 1846-1894". Scribner's Magazine. 16. December 1894.

- Kurshan, Virginia (March 23, 1982). "Charles Scribner's Sons Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

- "Ladies' Mile Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 2, 1989.

- "Scribner Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. May 6, 1980.

- "Scribner Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 14, 1976.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5. OCLC 9829395.

External links

- Virginia Kurshan (October 1979). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Scribner Building / Old Scribner Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2008. See also: "Accompanying three photos, exterior and interior, from 1979". Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. and "Accompanying nomination correspondence". Archived from the original on October 20, 2013.