Contents

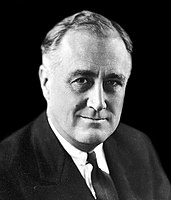

The 1936 United States presidential election was the 38th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 3, 1936. In the midst of the Great Depression, incumbent Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Republican Governor Alf Landon of Kansas in a landslide. Roosevelt won the highest share of the popular vote (60.8%) and the electoral vote (98.49%, carrying every state except Maine and Vermont) since the largely uncontested 1820 election. The sweeping victory consolidated the New Deal Coalition in control of the Fifth Party System.[2]

Roosevelt and Vice President John Nance Garner were re-nominated without opposition. With the backing of party leaders, Landon defeated progressive Senator William Borah at the 1936 Republican National Convention to win his party's presidential nomination. The populist Union Party nominated Congressman William Lemke for president.

The election took place as the Great Depression entered its eighth year. Roosevelt was still working to push the provisions of his New Deal economic policy through Congress and the courts. However, the New Deal policies he had already enacted, such as Social Security and unemployment benefits, had proven to be highly popular with most Americans. Landon, a political moderate, accepted much of the New Deal but criticized it for waste and inefficiency.

Roosevelt went on to win the greatest electoral landslide since the rise of hegemonic control between the Democratic and Republican parties in the 1850s. Roosevelt took 60.8% of the popular vote, while Landon won 36.56% and Lemke won 1.96%. Roosevelt carried every state except Maine and Vermont, which together cast eight electoral votes. By winning 523 electoral votes and 98.49% of the electoral vote total, this was the largest share of the Electoral College since 1820 and the second-largest number of raw electoral votes ever received by a candidate, and the largest ever for a Democrat. Roosevelt also won by the widest margin in the popular vote for a Democrat in history, although Lyndon Johnson would later win a slightly higher share of the popular vote in 1964. Roosevelt's 523 electoral votes marked the first of only three times in American history when a presidential candidate received over 500 electoral votes in a presidential election and made Roosevelt the only Democratic president to accomplish this feat.

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | John Nance Garner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32nd President of the United States (1933–1945) |

32nd Vice President of the United States (1933–1941) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | Henry Skillman Breckinridge | Upton Sinclair | John S. McGroarty | Al Smith |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. President from New York (1933–1945)

|

Assistant Secretary of War

(1913–1916) |

Novelist and Journalist from California

|

||

4,830,730 votes

|

136,407 votes

|

106,068 votes

|

61,391 votes

|

8,856

votes

|

Before his assassination, there was a challenge from Louisiana Senator Huey Long. But, due to his untimely death, President Roosevelt faced only one primary opponent other than various favorite sons. Henry Skillman Breckinridge, an anti-New Deal lawyer from New York, filed to run against Roosevelt in four primaries. Breckinridge's challenge of the popularity of the New Deal among Democrats failed miserably. In New Jersey, President Roosevelt did not file for the preference vote and lost that primary to Breckinridge, even though he did receive 19% of the vote on write-ins. Roosevelt's candidates for delegates swept the race in New Jersey and elsewhere. In other primaries, Breckinridge's best showing was 15% in Maryland. Overall, Roosevelt received 93% of the primary vote, compared to 2.5% for Breckinridge.[3]

The Democratic Party Convention was held in Philadelphia between July 23 and 27. The delegates unanimously re-nominated incumbents President Roosevelt and Vice-president John Nance Garner. At Roosevelt's request, the two-thirds rule, which had given the South a de facto veto power, was repealed.

| Presidential ballot | Vice-presidential ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | 1100 | John Nance Garner | 1100 |

Republican Party nomination

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alf Landon | Frank Knox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26th Governor of Kansas (1933–1937) |

Publisher of the Chicago Daily News (1931–1940) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the landslide defeat of former President Herbert Hoover at the previous presidential election in 1932, combined with devastating congressional losses that year, the Republican Party was largely seen as rudderless. In truth, Hoover maintained control of the party machinery and was hopeful of making a comeback, but any such hopes were dashed as soon as the 1934 mid-term elections, which saw further losses by the Republicans and made clear the popularity of the New Deal among the public. The expected third-party candidacy of prominent Senator Huey Long briefly reignited Hoover's hopes, but they were just as quickly ended by Long's assassination in September 1935. While Hoover thereafter refused to actively disclaim any potential draft efforts, he privately accepted that he was unlikely to be nominated, and even less likely to defeat Roosevelt in any rematch. Draft efforts did focus on former Vice-president Charles G. Dawes and Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary, two of the few prominent Republicans not to have been associated with Hoover's administration, but both men quickly disclaimed any interest in running.

The 1936 Republican National Convention was held in Cleveland, Ohio, between June 9 and 12. Although many candidates sought the Republican nomination, only two, Governor Landon and Senator William Borah from Idaho, were considered to be serious candidates. While County Attorney Earl Warren from California, Governor Warren Green of South Dakota, and Stephen A. Day from Ohio won their respective primaries, the seventy-year-old Borah, a well-known progressive and "insurgent," won the Wisconsin, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Oregon primaries, while also performing quite strongly in Knox's Illinois and Green's South Dakota.[4] The party machinery, however, almost uniformly backed Landon, a wealthy businessman and centrist, who won primaries in Massachusetts and New Jersey and dominated in the caucuses and at state party conventions.

With Knox withdrawing to become Landon's selection for vice-president (after the rejection of New Hampshire Governor Styles Bridges) and Day, Green, and Warren releasing their delegates, the tally at the convention was as follows:

- Alf Landon 984

- William Borah 19

Other nominations

Many people, most significantly Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley,[5] expected Huey Long, the colorful Democratic senator from Louisiana, to run as a third-party candidate with his "Share Our Wealth" program as his platform. Polls made during 1934 and 1935 suggested Long could have won between six[6] and seven million[7] votes, or approximately fifteen percent of the actual number cast in the 1936 election.

Popular support for Long's Share Our Wealth program raised the possibility of a 1936 presidential bid against incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt.[8][9] When questioned by the press, Long gave conflicting answers on his plans for 1936. While promising to support a progressive Republican like Sen. William Borah, Long claimed that he would only support a Share Our Wealth candidate.[10] At times, he even expressed the wish to retire: "I have less ambition to hold office than I ever had." However, in a later Senate speech, he admitted that he "might have a good parade to offer before I get through".[11] Long's son Russell B. Long believed that his father would have run on a third party ticket in 1936.[12] This is evidenced by Long's writing of a speculative book, My First Days in the White House, which laid out his plans for the presidency after the 1936 election.[13][14][note 1]

Long biographers T. Harry Williams and William Ivy Hair speculated that Long planned to challenge Roosevelt for the Democratic nomination in 1936, knowing he would lose the nomination but gain valuable publicity in the process. Then he would break from the Democrats and form a third party using the Share Our Wealth plan as its basis. He hoped to have the public support of Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist talk radio personality from Royal Oak, Michigan; Iowa agrarian radical Milo Reno; and other dissidents like Francis Townsend and the remnants of the End Poverty in California movement.[15] Diplomat Edward M. House warned Roosevelt "many people believe that he can do to your administration what Theodore Roosevelt did to the Taft administration in '12."[11]

In spring 1935, Long undertook a national speaking tour and regular radio appearances, attracting large crowds and increasing his stature.[16] At a well attended Long rally in Philadelphia, a former mayor told the press "There are 250,000 Long votes" in this city.[17] Regarding Roosevelt, Long boasted to the New York Times' Arthur Krock: "He's scared of me. I can out promise him, and he knows it."[18] While addressing reporters in late summer of 1935, Long proclaimed:

"I'll tell you here and now that Franklin Roosevelt will not be the next President of the United States. If the Democrats nominate Roosevelt and the Republicans nominate Hoover, Huey Long will be your next President."[19]

As the 1936 election approached, the Roosevelt administration grew increasingly concerned by Long's popularity.[17] Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley commissioned a secret poll in early 1935 "to find out if Huey's sales talks for his 'share the wealth' program were attracting many customers".[20] Farley's poll revealed that if Long ran on a third-party ticket, he would win about 4 million votes (about 10% of the electorate).[21] In a memo to Roosevelt, Farley wrote: "It was easy to conceive of a situation whereby Long by polling more than 3,000,000 votes, might have the balance of power in the 1936 election. For example, the poll indicated that he would command upwards of 100,000 votes in New York State, a pivotal state in any national election and a vote of that size could easily mean the difference between victory and defeat ... That number of votes would mostly come from our side and the result might spell disaster".[21]

In response, Roosevelt in a letter to his friend William E. Dodd, the US ambassador to Germany, wrote: "Long plans to be a candidate of the Hitler type for the presidency in 1936. He thinks he will have a hundred votes at the Democratic convention. Then he will set up as an independent with Southern and mid-western Progressives ... Thus he hopes to defeat the Democratic Party and put in a reactionary Republican. That would bring the country to such a state by 1940 that Long thinks he would be made dictator. There are in fact some Southerners looking that way, and some Progressives drifting that way ... Thus it is an ominous situation".[21]

However, Long was assassinated in September 1935. Some historians, including Long biographer T. Harry Williams, contend that Long had never, in fact, intended to run for the presidency in 1936. Instead, he had been plotting with Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist talk radio personality, to run someone else on the soon-to-be-formed "Share Our Wealth" Party ticket. According to Williams, the idea was that this candidate would split the left-wing vote with President Roosevelt, thereby electing a Republican president and proving the electoral appeal of Share Our Wealth. Long would then wait four years and run for president as a Democrat in 1940.

Prior to Long's death, leading contenders for the role of the sacrificial 1936 candidate included Idaho Senator William Borah, Montana Senator and running mate of Robert M. La Follette in 1924 Burton K. Wheeler, and Governor Floyd B. Olson of the Minnesota Farmer–Labor Party. After Long's assassination, however, the two senators lost interest in the idea, while Olson was diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer.

Father Coughlin, who had allied himself with Dr. Francis Townsend, a left-wing political activist who was pushing for the creation of an old-age pension system, and Rev. Gerald L. K. Smith, was eventually forced to run Representative William Lemke (R-North Dakota) as the candidate of the newly created "Union Party", with Thomas C. O'Brien, a lawyer and former District Attorney for Boston, as Lemke's running-mate. Lemke, who lacked the charisma and national stature of the other potential candidates, fared poorly in the election, barely managing two percent of the vote, and the party was dissolved the following year.

The Socialist Party again ran Norman Thomas who had been their candidate in 1928 and for Vice President George A. Nelson, a Wisconsin dairy farmer and writer on farming issues.

The Communist Party (CPUSA) nominated Earl Browder and for vice president their 1932 candidate James W. Ford, who had been the first African American nominee.

William Dudley Pelley, Chief of the Silver Shirts Legion, ran on the ballot for the Christian Party in Washington State, but won fewer than two thousand votes.

Campaign

Pre-election polling

This election is notable for The Literary Digest poll, which was based on ten million questionnaires mailed to readers and potential readers; 2.38 million were returned. The Literary Digest had correctly predicted the winner of the last five elections, and announced in its October 31 issue that Landon would be the winner with 57.08% of the vote (v Roosevelt) and 370 electoral votes.

The cause of this mistake has often been attributed to improper sampling: more Republicans subscribed to the Literary Digest than Democrats, and were thus more likely to vote for Landon than Roosevelt. Indeed, every other poll made at this time predicted Roosevelt would win, although most expected him to garner no more than 370 electoral votes.[22] However, a 1976 article in The American Statistician demonstrates that the actual reason for the error was that the Literary Digest relied on voluntary responses. As the article explains, the 2.38 million "respondents who returned their questionnaires represented only that subset of the population with a relatively intense interest in the subject at hand, and as such constitute in no sense a random sample ... it seems clear that the minority of anti-Roosevelt voters felt more strongly about the election than did the pro-Roosevelt majority."[23] A more detailed study in 1988 showed that both the initial sample and non-response bias were contributing factors, and that the error due to the initial sample taken alone would not have been sufficient to predict the Landon victory.[24]

The magnitude of the error by the Literary Digest (39.08% for the popular vote margin for Landon v Roosevelt) destroyed the magazine's credibility, and it folded within 18 months of the election, while George Gallup, an advertising executive who had begun a scientific poll, predicted that Roosevelt would win the election, based on a quota sample of 50,000 people.

His correct predictions made public opinion polling a critical element of elections for journalists, and indeed for politicians. The Gallup Poll would become a staple of future presidential elections, and remains one of the most prominent election polling organizations.

Campaign

Landon proved to be an ineffective campaigner who rarely travelled. Most of the attacks on FDR and Social Security were developed by Republican campaigners rather than Landon himself. In the two months after his nomination, he made no campaign appearances. Columnist Westbrook Pegler lampooned, "Considerable mystery surrounds the disappearance of Alfred M. Landon of Topeka, Kansas ... The Missing Persons Bureau has sent out an alarm bulletin bearing Mr. Landon's photograph and other particulars, and anyone having information of his whereabouts is asked to communicate direct with the Republican National Committee."[25]

Landon respected and admired Roosevelt and accepted most of the New Deal but objected that it was hostile to business and involved too much waste and inefficiency. Late in the campaign, Landon accused Roosevelt of corruption – that is, of acquiring so much power that he was subverting the Constitution:

The President spoke truly when he boasted ... 'We have built up new instruments of public power.' He spoke truly when he said these instruments could provide 'shackles for the liberties of the people ... and ... enslavement for the public.' These powers were granted with the understanding that they were only temporary. But after the powers had been obtained, and after the emergency was clearly over, we were told that another emergency would be created if the power was given up. In other words, the concentration of power in the hands of the President was not a question of temporary emergency. It was a question of permanent national policy. In my opinion the emergency of 1933 was a mere excuse ... National economic planning—the term used by this Administration to describe its policy—violates the basic ideals of the American system ... The price of economic planning is the loss of economic freedom. And economic freedom and personal liberty go hand in hand.[26]

Franklin Roosevelt's most notable speech in the 1936 campaign was an address he gave in Madison Square Garden in New York City on 31 October. Roosevelt offered a vigorous defense of the New Deal:

For twelve years this Nation was afflicted with hear-nothing, see-nothing, do-nothing Government. The Nation looked to Government but the Government looked away. Nine mocking years with the golden calf and three long years of the scourge! Nine crazy years at the ticker and three long years in the breadlines! Nine mad years of mirage and three long years of despair! Powerful influences strive today to restore that kind of government with its doctrine that that Government is best which is most indifferent.

For nearly four years you have had an Administration which instead of twirling its thumbs has rolled up its sleeves. We will keep our sleeves rolled up.

We had to struggle with the old enemies of peace—business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking, class antagonism, sectionalism, war profiteering. They had begun to consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs. We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.

Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.[27]

Results

Roosevelt won in a landslide, carrying 46 of the 48 states and bringing in many additional Democratic members of Congress. After Lyndon B. Johnson's 61.05% share of the popular vote in 1964, Roosevelt's 60.8% is the second-largest percentage in U.S. history (since 1824, when the vast majority of or all states have had a popular vote), and his 98.49% of the electoral vote is the highest in two-party competition.

The Republican Party saw its total in the United States House of Representatives reduced to 88 seats and in the United States Senate to 16 seats in their respective elections and only won four governorships in the 1936 elections.[28] Roosevelt won the largest number of electoral votes ever recorded at that time, and has so far only been surpassed by Ronald Reagan in 1984, when seven more electoral votes were available to contest. Garner also won the highest percentage of the electoral vote of any vice president.

Landon won only eight electoral votes, tying William Howard Taft's total in his unsuccessful re-election campaign in 1912. As of 2023, this is the equal lowest electoral vote total for a major-party candidate; the lowest number since was Reagan's 1984 opponent, Walter Mondale, who won only thirteen electoral votes.

Roosevelt's net vote totals in the twelve largest cities increased from 1,791,000 votes in the 1932 election to 3,479,000 votes which was the highest for any presidential candidate from 1920 to 1948. Philadelphia and Columbus, Ohio, which had voted for Hoover in the 1932 election, voted for Roosevelt in the 1936 election. Although the majority of black voters had been Republican in the 1932 election Roosevelt won two-thirds of black voters in the 1936 election.[28]

Norman Thomas, who had received 884,885 votes in the 1932 election saw his totals decrease to 187,910.[28]

Roosevelt also took 98.57% of the vote in South Carolina, the largest recorded vote percentage of any candidate in any one state with an opponent in any presidential election (this excludes Andrew Jackson in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi and Missouri in 1832, who won 100% of the vote in these states as he was unopposed).[29]

This was the last Democratic landslide in the West, as Democrats won every state except Kansas (Landon's home state) by more than 10%. West of the Great Plains States, Roosevelt only lost eight counties. Since 1936, only Richard Nixon in 1972 (winning all but 19 counties)[citation needed] and Ronald Reagan in 1980 (winning all but twenty counties) have even approached such a disproportionate ratio.

Of the 3,095 counties, parishes and independent cities making returns, Roosevelt won in 2,634 (85 percent) while Landon carried 461 (15 percent); this was one of the few measures by which Landon's campaign was more successful than Hoover's had been four years prior, with Landon winning 87 more counties than Hoover did, albeit mostly in less populous parts of the country. Democrats also expanded their majorities in Congress, winning control of over three-quarters of the seats in each house.

The election saw the consolidation of the New Deal coalition; while the Democrats lost some of their traditional allies in big business, high-income voters, businessmen and professionals, they were replaced by groups such as organized labor and African Americans, the latter of whom voted Democratic for the first time since the Civil War,[citation needed] and made major gains among the poor and other minorities. Roosevelt won 86 percent of the Jewish vote, 81 percent of the Catholics, 80 percent of union members, 76 percent of Southerners, 76 percent of Blacks in northern cities, and 75 percent of people on relief. Roosevelt also carried 102 of the nation's 106 cities with a population of 100,000 or more.[30]

Some political pundits predicted the Republicans, whom many voters blamed for the Great Depression, would soon become an extinct political party.[31] However, the Republicans would make a strong comeback in the 1938 congressional elections, and while they would remain a potent force in Congress,[31] they were not able to regain control of the House or the Senate until 1946, and would not regain the Presidency until 1952.

The Electoral College results, in which Landon only won Maine and Vermont, inspired Democratic Party chairman James Farley - who had in fact declared during the campaign that Roosevelt would lose only these two states - [22] to amend the then-conventional political wisdom of "As Maine goes, so goes the nation" into "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont." In fact, since then, the states of Vermont and Maine voted for the same candidate in every election except the 1968 presidential election. Additionally, a prankster posted a sign on Vermont's border with New Hampshire the day after the 1936 election, reading, "You are now leaving the United States."[22]

This was the last election in which Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota would vote Democratic until 1964. Of these states, only Indiana would vote Democratic again after 1964 (for Barack Obama in 2008), making this the penultimate time a Democrat won any of the Great Plains states.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Franklin D. Roosevelt (incumbent) | Democratic | New York | 27,752,648 | 60.80% | 523 | John Nance Garner | Texas | 523 |

| Alf Landon | Republican | Kansas | 16,681,862 | 36.54% | 8 | Frank Knox | Illinois | 8 |

| William Lemke | Union | North Dakota | 892,378 | 1.95% | 0 | Thomas C. O'Brien | Massachusetts | 0 |

| Norman Thomas | Socialist | New York | 187,910 | 0.41% | 0 | George A. Nelson | Wisconsin | 0 |

| Earl Browder | Communist | Kansas | 79,315 | 0.17% | 0 | James W. Ford | New York | 0 |

| D. Leigh Colvin | Prohibition | New York | 37,646 | 0.08% | 0 | Claude A. Watson | California | 0 |

| John W. Aiken | Socialist Labor | Connecticut | 12,799 | 0.03% | 0 | Emil F. Teichert | New York | 0 |

| Other | 3,141 | 0.00% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 45,647,699 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1936 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

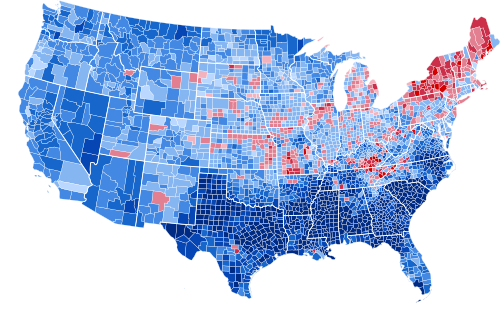

Geography of results

-

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

-

Presidential election results by county

-

Democratic presidential election results by county

-

Republican presidential election results by county

-

"Other" presidential election results by county

-

American Labor presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

-

Cartogram of American Labor presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source:[32]

| States/districts won by Roosevelt/Garner |

| States/districts won by Landon/Knox |

| Franklin D. Roosevelt Democratic |

Alfred Landon Republican |

William Lemke Union |

Norman Thomas Socialist |

Other | Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 11 | 238,136 | 86.38 | 11 | 35,358 | 12.82 | - | 551 | 0.20 | - | 242 | 0.09 | - | 1,397 | 0.51 | - | 202,838 | 73.56 | 275,244 | AL |

| Arizona | 3 | 86,722 | 69.85 | 3 | 33,433 | 26.93 | - | 3,307 | 2.66 | - | 317 | 0.26 | - | 384 | 0.31 | - | 53,289 | 42.92 | 124,163 | AZ |

| Arkansas | 9 | 146,765 | 81.80 | 9 | 32,039 | 17.86 | - | 4 | 0.00 | - | 446 | 0.25 | - | 169 | 0.09 | - | 114,726 | 63.94 | 179,423 | AR |

| California | 22 | 1,766,836 | 66.95 | 22 | 836,431 | 31.70 | - | - | - | - | 11,331 | 0.43 | - | 24,284 | 0.92 | - | 930,405 | 35.26 | 2,638,882 | CA |

| Colorado | 6 | 295,021 | 60.37 | 6 | 181,267 | 37.09 | - | 9,962 | 2.04 | - | 1,593 | 0.33 | - | 841 | 0.17 | - | 113,754 | 23.28 | 488,684 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 382,129 | 55.32 | 8 | 278,685 | 40.35 | - | 21,805 | 3.16 | - | 5,683 | 0.82 | - | 2,421 | 0.35 | - | 103,444 | 14.98 | 690,723 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 69,702 | 54.62 | 3 | 57,236 | 44.85 | - | 442 | 0.35 | - | 172 | 0.13 | - | 51 | 0.04 | - | 12,466 | 9.77 | 127,603 | DE |

| Florida | 7 | 249,117 | 76.10 | 7 | 78,248 | 23.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 170,869 | 52.20 | 327,365 | FL |

| Georgia | 12 | 255,364 | 87.10 | 12 | 36,942 | 12.60 | - | 141 | 0.05 | - | 68 | 0.02 | - | 660 | 0.23 | - | 218,422 | 74.50 | 293,175 | GA |

| Idaho | 4 | 125,683 | 62.96 | 4 | 66,256 | 33.19 | - | 7,678 | 3.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 59,427 | 29.77 | 199,617 | ID |

| Illinois | 29 | 2,282,999 | 57.70 | 29 | 1,570,393 | 39.69 | - | 89,439 | 2.26 | - | 7,530 | 0.19 | - | 6,161 | 0.16 | - | 712,606 | 18.01 | 3,956,522 | IL |

| Indiana | 14 | 934,974 | 56.63 | 14 | 691,570 | 41.89 | - | 19,407 | 1.18 | - | 3,856 | 0.23 | - | 1,090 | 0.07 | - | 243,404 | 14.74 | 1,650,897 | IN |

| Iowa | 11 | 621,756 | 54.41 | 11 | 487,977 | 42.70 | - | 29,687 | 2.60 | - | 1,373 | 0.12 | - | 1,940 | 0.17 | - | 133,779 | 11.71 | 1,142,733 | IA |

| Kansas | 9 | 464,520 | 53.67 | 9 | 397,727 | 45.95 | - | 497 | 0.06 | - | 2,770 | 0.32 | - | - | - | - | 66,793 | 7.72 | 865,014 | KS |

| Kentucky | 11 | 541,944 | 58.51 | 11 | 369,702 | 39.92 | - | 12,501 | 1.35 | - | 632 | 0.07 | - | 1,424 | 0.15 | - | 172,242 | 18.60 | 926,203 | KY |

| Louisiana | 10 | 292,894 | 88.82 | 10 | 36,791 | 11.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 93 | 0.00 | - | 256,103 | 77.66 | 329,778 | LA |

| Maine | 5 | 126,333 | 41.52 | - | 168,823 | 55.49 | 5 | 7,581 | 2.49 | - | 783 | 0.26 | - | 720 | 0.24 | - | -42,490 | -13.97 | 304,240 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 389,612 | 62.35 | 8 | 231,435 | 37.04 | - | - | - | - | 1,629 | 0.26 | - | 2,220 | 0.36 | - | 158,177 | 25.31 | 624,896 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 17 | 942,716 | 51.22 | 17 | 768,613 | 41.76 | - | 118,639 | 6.45 | - | 5,111 | 0.28 | - | 5,278 | 0.29 | - | 174,103 | 9.46 | 1,840,357 | MA |

| Michigan | 19 | 1,016,794 | 56.33 | 19 | 699,733 | 38.76 | - | 75,795 | 4.20 | - | 8,208 | 0.45 | - | 4,568 | 0.25 | - | 317,061 | 17.56 | 1,805,098 | MI |

| Minnesota | 11 | 698,811 | 61.84 | 11 | 350,461 | 31.01 | - | 74,296 | 6.58 | - | 2,872 | 0.25 | - | 3,535 | 0.31 | - | 348,350 | 30.83 | 1,129,975 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 157,318 | 97.06 | 9 | 4,443 | 2.74 | - | - | - | - | 329 | 0.20 | - | - | - | - | 152,875 | 94.31 | 162,090 | MS |

| Missouri | 15 | 1,111,043 | 60.76 | 15 | 697,891 | 38.16 | - | 14,630 | 0.80 | - | 3,454 | 0.19 | - | 1,617 | 0.09 | - | 413,152 | 22.59 | 1,828,635 | MO |

| Montana | 4 | 159,690 | 69.28 | 4 | 63,598 | 27.59 | - | 5,549 | 2.41 | - | 1,066 | 0.46 | - | 609 | 0.26 | - | 96,092 | 41.69 | 230,512 | MT |

| Nebraska | 7 | 347,445 | 57.14 | 7 | 247,731 | 40.74 | - | 12,847 | 2.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 99,714 | 16.40 | 608,023 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 31,925 | 72.81 | 3 | 11,923 | 27.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20,002 | 45.62 | 43,848 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 108,460 | 49.73 | 4 | 104,642 | 47.98 | - | 4,819 | 2.21 | - | - | - | - | 193 | 0.09 | - | 3,818 | 1.75 | 218,114 | NH |

| New Jersey | 16 | 1,083,850 | 59.54 | 16 | 720,322 | 39.57 | - | 9,407 | 0.52 | - | 3,931 | 0.22 | - | 2,927 | 0.16 | - | 364,128 | 19.97 | 1,820,437 | NJ |

| New Mexico | 3 | 106,037 | 62.69 | 3 | 61,727 | 36.50 | - | 924 | 0.55 | - | 343 | 0.20 | - | 105 | 0.06 | - | 44,310 | 26.20 | 169,176 | NM |

| New York | 47 | 3,293,222 | 58.85 | 47 | 2,180,670 | 38.97 | - | - | - | - | 86,897 | 1.55 | - | 35,609 | 0.64 | - | 1,112,552 | 19.88 | 5,596,398 | NY |

| North Carolina | 13 | 616,141 | 73.40 | 13 | 223,283 | 26.60 | - | 2 | 0.00 | - | 21 | 0.00 | - | 17 | 0.00 | - | 392,858 | 46.80 | 839,464 | NC |

| North Dakota | 4 | 163,148 | 59.60 | 4 | 72,751 | 26.58 | - | 36,708 | 13.41 | - | 552 | 0.20 | - | 557 | 0.20 | - | 90,397 | 33.03 | 273,716 | ND |

| Ohio | 26 | 1,747,140 | 57.99 | 26 | 1,127,855 | 37.44 | - | 132,212 | 4.39 | - | 117 | 0.00 | - | 5,265 | 0.17 | - | 619,285 | 20.56 | 3,012,589 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 11 | 501,069 | 66.83 | 11 | 245,122 | 32.69 | - | - | - | - | 2,221 | 0.30 | - | 1,328 | 0.18 | - | 255,947 | 34.14 | 749,740 | OK |

| Oregon | 5 | 266,733 | 64.42 | 5 | 122,706 | 29.64 | - | 21,831 | 5.27 | - | 2,143 | 0.52 | - | 608 | 0.15 | - | 144,027 | 34.79 | 414,021 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 36 | 2,353,987 | 56.88 | 36 | 1,690,200 | 40.84 | - | 67,468 | 1.63 | - | 14,599 | 0.35 | - | 12,172 | 0.29 | - | 663,787 | 16.04 | 4,138,426 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 165,238 | 53.10 | 4 | 125,031 | 40.18 | - | 19,569 | 6.29 | - | - | - | - | 1,340 | 0.43 | - | 40,207 | 12.92 | 311,178 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 113,791 | 98.57 | 8 | 1,646 | 1.43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 112,145 | 97.15 | 115,437 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 160,137 | 54.02 | 4 | 125,977 | 42.49 | - | 10,338 | 3.49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 34,160 | 11.52 | 296,472 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 328,083 | 68.85 | 11 | 146,520 | 30.75 | - | 296 | 0.06 | - | 686 | 0.14 | - | 953 | 0.20 | - | 181,563 | 38.10 | 476,538 | TN |

| Texas | 23 | 734,485 | 87.08 | 23 | 103,874 | 12.31 | - | 3,281 | 0.39 | - | 1,075 | 0.13 | - | 767 | 0.09 | - | 630,611 | 74.76 | 843,482 | TX |

| Utah | 4 | 150,246 | 69.34 | 4 | 64,555 | 29.79 | - | 1,121 | 0.52 | - | 432 | 0.20 | - | 323 | 0.15 | - | 85,691 | 39.55 | 216,677 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 62,124 | 43.24 | - | 81,023 | 56.39 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 542 | 0.38 | - | -18,899 | -13.15 | 143,689 | VT |

| Virginia | 11 | 234,980 | 70.23 | 11 | 98,336 | 29.39 | - | 233 | 0.07 | - | 313 | 0.09 | - | 728 | 0.22 | - | 136,644 | 40.84 | 334,590 | VA |

| Washington | 8 | 459,579 | 66.38 | 8 | 206,892 | 29.88 | - | 17,463 | 2.52 | - | 3,496 | 0.50 | - | 4,908 | 0.71 | - | 252,687 | 36.50 | 692,338 | WA |

| West Virginia | 8 | 502,582 | 60.56 | 8 | 325,358 | 39.20 | - | - | - | - | 832 | 0.10 | - | 1,173 | 0.14 | - | 177,224 | 21.35 | 829,945 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 802,984 | 63.80 | 12 | 380,828 | 30.26 | - | 60,297 | 4.79 | - | 10,626 | 0.84 | - | 3,825 | 0.30 | - | 422,156 | 33.54 | 1,258,560 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 62,624 | 60.58 | 3 | 38,739 | 37.47 | - | 1,653 | 1.60 | - | 200 | 0.19 | - | 166 | 0.16 | - | 23,885 | 23.10 | 103,382 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 531 | 27,752,648 | 60.80 | 523 | 16,681,862 | 36.54 | 8 | 892,378 | 1.95 | - | 187,910 | 0.41 | - | 132,901 | 0.29 | - | 11,070,786 | 24.25 | 45,647,699 | US |

States that flipped from Republican to Democratic

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (4 electoral votes):

- New Hampshire, 1.75% (3,818 votes)

Margin of victory greater than 5% but less than 10% (29 electoral votes):

- Kansas, 7.72% (66,793 votes)

- Massachusetts, 9.46% (174,103 votes)

- Delaware, 9.77% (12,466 votes)

Tipping point state:

- Ohio, 20.56% (619,285 votes)

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Issaquena County, Mississippi 100.00%

- Horry County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Lancaster County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Greensville County, Virginia 100.00%

- Edgefield County, South Carolina 99.92%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Jackson County, Kentucky 89.05%

- Johnson County, Tennessee 84.39%

- Owsley County, Kentucky 83.02%

- Leslie County, Kentucky 81.39%

- Avery County, North Carolina 77.98%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

- Burke County, North Dakota 31.63%

- Sheridan County, North Dakota 28.88%

- Hettinger County, North Dakota 28.25%

- Mountrail County, North Dakota 25.73%

- Steele County, North Dakota 24.30%

See also

- History of the United States (1918–1945)

- 1936 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1936 United States Senate elections

- Second inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Earl Browder

- Huey Long

Notes

References

- ^ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- ^ Paul Kleppner et al. The Evolution of American Electoral Systems pp 219–225.

- ^ Kalb, Deborah, ed. (2010). Guide to U.S. Elections. Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-60426-536-1.

- ^ "Borah and Nye want to form new national party. Washington, D.C., May 6. There have been new rumors that Senator Borah of Idaho and Senator Nye of North Dakota and other insurgent Republicans want to start a new National party with the purpose of unhorsing the present Republican National Committee. The leadership will fall to Senators William E. Borah and Gerald P. Nye caught as they were confering together at the Capitol today, 5/6/1937". Library of Congress. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Kane, Harnett; Huey Long's Louisiana Hayride, p. 126. ISBN 1455606111

- ^ Hair, William Ivy; The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long; ISBN 080712124X

- ^ Carpenter, Ronald H.; Father Charles E. Coughlin: Surrogate Spokesman for the Disaffected; p. 62 ISBN 0-313-29040-7

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 121.

- ^ Leuchtenburg, William E. (Fall 1985). "FDR And The Kingfish". American Heritage. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 122.

- ^ a b Snyder (1975), p. 125.

- ^ Snyder (1975), pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Brown, Francis (September 29, 1935). "Huey Long as Hero and as Demagogue; My First Days in the White House. By Huey Pierce Long. 146 pp. Harrisburg, Pa.: The Telegraph Press". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Sanson (2006), p. 274.

- ^ Kennedy (2005) [1999], pp. 239–40.

- ^ Hair (1996), p. 284.

- ^ a b Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 240.

- ^ Snyder (1975), p. 128.

- ^ "FDR And The Kingfish".

- ^ Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 239.

- ^ a b c Kennedy (2005) [1999], p. 241.

- ^ a b c Derbyshire, Wyn; Dark Realities: America's Great Depression; p. 213 ISBN 1907444777

- ^ Bryson, Maurice C. 'The Literary Digest Poll: Making of a Statistical Myth' The American Statistician, 30(4):November 1976

- ^ Squire, Peverill (1988). "Why the 1936 Literary Digest Poll Failed". Public Opinion Quarterly. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Time, August 31, 1936

- ^ Time October 26, 1936

- ^ "Franklin Delano Roosevelt Madison Square Garden Speech (1936)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Paul (1974). Political Parties In American History, Volume 3, 1890-present. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ^ @millenarian22 (July 31, 2020). "#ElectionTwitter Map of which Party/Presidential Candidate got the highest % of the vote ever in each state, from 1868-2016. This isn't an average, but just the single highest % achieved by any candidate in each state. SC sets the record with 98.6% of the vote for FDR in 1936" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Mary E. Stuckey (2015). Voting Deliberatively: FDR and the 1936 Presidential Campaign. Penn State UP. p. 19. ISBN 9780271071923.

- ^ a b Gould, Lewis L.; The Republicans: A History of the Grand Old Party. ISBN 0199936625

- ^ "1936 Presidential General Election Data - National". Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ "1936 Presidential General Election Data - National". Retrieved April 8, 2013.

Works cited

- Hair, William Ivy (1991). The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807141069.

- Sanson, Jerry P. (Summer 2006). ""What He Did and What He Promised to Do... ": Huey Long and the Horizons of Louisiana Politics". The Journal of Louisiana Historical. 47 (3): 261–276. JSTOR 4234200.

- Snyder, Robert E. (Spring 1975). "Huey Long and the Presidential Election of 1936". The Journal of Louisiana Historical. 16 (2): 117–143. JSTOR 4231456.

Further reading

- Andersen, Kristi. The Creation of a Democratic Majority: 1928–1936 (1979), statistical

- Brown, Courtney. "Mass dynamics of US presidential competitions, 1928–1936." American Political Science Review 82.4 (1988): 1153–1181. online

- Burns, James MacGregor. Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox (1956)

- Campbell, James E. "Sources of the new deal realignment: The contributions of conversion and mobilization to partisan change." Western Political Quarterly 38.3 (1985): 357–376. online

- Fadely, James Philip. "Editors, Whistle Stops, and Elephants: the Presidential Campaign of 1936 in Indiana." Indiana Magazine of History 1989 85(2): 101–137. ISSN 0019-6673

- Harrell, James A. "Negro Leadership in the Election Year 1936." Journal of Southern History 34.4 (1968): 546–564. online

- Kennedy, Patrick D. "Chicago's Irish Americans and the Candidacies of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1932-1944." Illinois Historical Journal 88.4 (1995): 263–278. online

- Leuchtenburg, William E. "Election of 1936", in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed., A History of American Presidential Elections vol 3 (1971), analysis and primary documents

- McCoy, Donald. Landon of Kansas (1968)

- Nicolaides, Becky M. "Radio Electioneering in the American Presidential Campaigns of 1932 and 1936", Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, June 1988, Vol. 8 Issue 2, pp. 115–138

- Pietrusza, David Roosevelt Sweeps Nation: FDR’s 1936 Landslide and the Triumph of the Liberal Ideal (2022).

- Savage, Sean J. "The 1936-1944 Campaigns", in William D. Pederson, ed. A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt (2011) pp 96–113 online

- Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M. The Politics of Upheaval (1960)

- Sheppard, Si. The Buying of the Presidency? Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal, and the Election of 1936. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2014.

- Shover, John L. "The emergence of a two-party system in Republican Philadelphia, 1924-1936." Journal of American History 60.4 (1974): 985–1002. online

- Spencer, Thomas T. "'Labor is with Roosevelt:' The Pennsylvania Labor Non-Partisan League and the Election of 1936." Pennsylvania History 46.1 (1979): 3–16. online

Primary sources

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds.; Public Opinion, 1935–1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls from USA

- Gallup, George H. ed. The Gallup Poll, Volume One 1935–1948 (1972) statistical reports on each poll

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956