Contents

Fort Stanton was a Civil War-era fortification constructed in the hills above Anacostia in the District of Columbia, USA, and was intended to prevent Confederate artillery from threatening the Washington Navy Yard. It also guarded the approach to the bridge that connected Anacostia (then known as Uniontown) with Washington. Built in 1861, the fort was expanded throughout the war and was joined by two subsidiary forts: Fort Ricketts and Fort Snyder. Following the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, it was dismantled and the land returned to its original owner. It never saw combat. Abandoned after the war, the site of the fort was planned to be part of a grand "Fort Circle" park system encircling the city of Washington. Though this system of interconnected parks never was fully implemented, the site of the fort is today a park maintained by the National Park Service, and a historical marker stands near the fort's original location.[1]

Planning and construction

Following the secession of Virginia and that state joining the Confederacy, Federal troops marched from Washington into the Arlington region of northern Virginia. The move was intended to forestall any attempt by Virginia militia or Confederate soldiers to seize the capital city of the United States. Over the next seven weeks, forts were constructed along the banks of the Potomac River and at the approaches to each of the three major bridges (Chain Bridge, Long Bridge, and Aqueduct Bridge) connecting Virginia to Washington and Georgetown.[2]

While the Potomac River forts were being built, planning and surveying were ordered for an enormous new ring of forts to protect the city. Unlike the fortifications under construction, the new forts would defend the city in all directions, not just the most direct route through Arlington. In mid-July, this work was interrupted by the First Battle of Bull Run. As the Army of Northeastern Virginia marched south to Manassas, the soldiers previously assigned to construction duties marched instead to battle. In the days that followed the Union defeat at Bull Run, panicked efforts were made to defend Washington from what was perceived as an imminent Confederate attack.[3] The makeshift trenches and earthworks that resulted were largely confined to Arlington and the direct approaches to Washington.

On July 26, 1861, five days after the battle, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was named commander of the military district of Washington and the subsequently renamed Army of the Potomac. Upon arriving in Washington, McClellan was appalled by the condition of the city's defenses. "In no quarter were the dispositions for defense such as to offer a vigorous resistance to a respectable body of the enemy, either in the position and numbers of the troops or the number and character of the defensive works... not a single defensive work had been commenced on the Maryland side. There was nothing to prevent the enemy shelling the city from heights within easy range, which could be occupied by a hostile column almost without resistance."[4]

To remedy the situation, one of McClellan's first orders upon taking command was to greatly expand Washington's defenses. At all points of the compass, forts and entrenchments would be constructed in sufficient strength to defeat any attack. One area of particular concern was the region of Maryland south of the Anacostia River. Confederate artillery floated across the Potomac in secret and mounted south of the river could threaten the Washington Navy Yard and Washington Arsenal, both of which lay at the junction of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers.

To prevent that threat from coming to pass, Brig. Gen. John G. Barnard, chief engineer of the defenses of Washington, directed that a line of forts be constructed on the heights southeast of the Anacostia River. From Fort Greble at the western end to Fort Mahan at the eastern end, the forts along the Eastern Branch River (as the Anacostia was then known) were not intended to constitute a continuous defensive line as was the Arlington Line that defended the Virginia approaches to the city. Instead, they were merely intended to deny Confederate artillery the position and warn of any sneak attack upon Washington from the southeast. General Barnard illustrated this in an October 1862 report, saying, "As the enemy cannot enter the city from this direction, the object of the works is to prevent him seizing these heights, and occupying them long enough to shell the navy-yard and arsenal. For this, the works must be made secure against assault, and auxiliary to this object is the construction of roads by which succor can be readily thrown to any point menaced."[5]

Fort Stanton, located in the Garfield Heights, was the first fort of this line to begin construction. Begun in September 1861, the fort was located almost directly south of the Washington Navy Yard and the Navy Yard Bridge that crossed the Anacostia River and connected Uniontown, a suburb of Washington, with the city itself. Work progressed rapidly, and by Christmas, a report by General Barnard indicated the fort was "completed and armed."[6]

Despite that speed, not everything went in the engineers' favor. Barnard's report indicates "the sites of Fort... Stanton and others were entirely wooded, which, in conjunction with the broken character of the ground, has made the selection of sites frequently very embarrassing and the labor of preparing them very great."[7] The experience of surveying and preparing the site of Fort Stanton would serve the engineers well in the construction of future forts around Washington and in service to the Army of the Potomac. Clearing brush and forest away from the site of Fort Stanton allowed for clear fields of fire for the fort's cannon for several hundred yards in each direction, a technique that would be applied (and later used) to great effect at Fort Stevens.

Wartime operation

By the summer of 1862, the fort was already being heavily used. A garrison had been assigned in the winter, and the 1862 report of the Commission to Study the Defenses of Washington describes Fort Stanton as "a work of considerable dimensions, well built, and tolerably well armed. Casemates for reversed fires are recommended in northwest and southwest counterscarp angles, and platforms for two or three rifled guns on the east front. The deep ravine which flanks this work on two sides requires some additional precaution, and further study of it is recommended."[8]

The commission had been ordered by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to inspect each of the forts surrounding Washington in late 1862 and make a report on the deficiencies of each. In addition to examining Fort Stanton, the commission analyzed two smaller works that supported Fort Stanton. Fort Ricketts was identified in the report as "a battery intended to see the ravine in front of Fort Stanton, which it does but imperfectly," while Fort Snyder "may be regarded as an outwork to Fort Stanton, guarding the head of one branch of the ravine just mentioned. Except additional platforms for field guns, and a ditch in front of the gorge stockade, and blockhouses, nothing further seems necessary."[9]

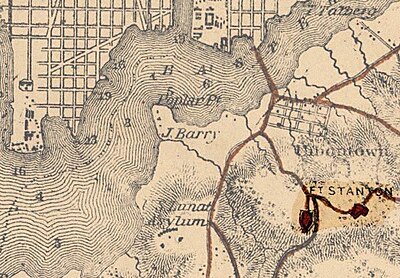

A military road was constructed from Uniontown to the fort to support Fort Stanton and its two subsidiary positions. Tributary roads led from Fort Stanton to the other forts in the Eastern Branch line. These roads were eventually widened into a large ring road that circled most of the 37-mile perimeter of Washington, which can be noted in the 1865 map[10] of the city's defenses. In fall 1862, however, the commission examining the defenses noted that "the work on roads about Washington requires ten regiments for twenty days ... or an equivalent of labor in some other shape."[11]

An 1864 inspection by Brig. Gen. Albion P. Howe, Inspector-General of Artillery, found Fort Stanton to be well-equipped but the garrison poorly trained. The fort was armed with six 32-pounder barbettes, three 24-pounder field howitzers, four 8-inch siege howitzers, one Coehorn mortar, and one 4-inch rifled mortar. The ammunition was listed as "complete and servicible," but the 131 men of a single company of the Heavy Massachusetts Volunteer Artillery that comprised the garrison at the time were "not drilled in artillery; some in infantry."[12]

Following the Confederate raid on Washington that resulted in the Battle of Fort Stevens, new assessments were made of weak spots in Washington's defenses. In the three years between the construction of Fort Stanton and the attack on Fort Stevens, Fort Stanton's perimeter had been greatly increased with the addition of two subsidiary forts and additional rifle pits and trenches, as well as the completion of the military ring road. A report by Maj. Gen. Christopher C. Augur of the U.S. Volunteers recommended Fort Stanton receive one 32-pounder howitzer, two 4½-inch rifled guns, four 12-pounder howitzers, and two 12-pounder Napoleons to bolster its defenses and control its position at the center of the Eastern Branch defenses.[13]

In August 1864, Gen. Barnard was replaced in his capacity as chief engineer of the defenses of Washington by Lt. Col. Barton S. Alexander. With the war winding down, Alexander's duties consisted primarily of maintaining and expanding the already-existing defenses rather than building new forts as Barnard had done. An October 1864 report from Col. Alexander to Brig. Gen. Richard Delafield, head of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, lists a series of improvements to Fort Stanton's already-impressive defenses. "Constructing three bastions, two new magazines, bomb-proofs, traverses, platforms, embrasures, grading glacis, and renewing abatis," the report reads.[14]

Post-war use

After the surrender of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the primary reason for garrisoned defenses protecting Washington ceased to exist. Initial recommendations by Col. Alexander, chief engineer of the Washington defenses, were to divide the defenses into three classes: those that should be kept active (first-class), those that should be mothballed and kept in a reserve state (second-class), and those that should be abandoned entirely (third-class). Fort Stanton fell into the first-class category, as it was thought that the fort would be needed to defend the Washington Navy Yard.[15]

Thanks to its status as a first-class fortification, Fort Stanton continued to receive regular maintenance and was continually garrisoned even after the final armistice. Work was even done to strengthen the defenses, as a stockade was added in the summer of 1865. The fort's parapets were re-sodded with fresh grass for better traction and to improve the look of the fortification.[16]

Abandonment

With the conclusion of the fighting, however, military budgets were slashed, and even the forts that were designated for second- and first-class status were deemed surplus. The guns were removed, surplus equipment sold, and the land returned to its original owners. Fort Stanton itself was officially closed on March 20, 1866.[17] Following the closure, the fort was abandoned to the elements, and the woods of Anacostia rapidly reclaimed the land.

In 1873, journalist George Alfred Townsend published Washington, Outside and Inside. A Picture and A Narrative of the Origin, Growth, Excellences, Abuses, Beauties, and Personages of Our Governing City, a work covering the history of Washington from its inception to the then-present day. The Civil War defenses of Washington figure prominently in the later portions of the book. He uses the state of Fort Stanton as an example of what had become of the forts a decade after they had been built.

I climbed the high hills one day on the other side, and pushing up by-paths through bramble and laurel, gained the ramparts of old Fort Stanton. How old already seem those fortresses, drawing their amphitheatre around the Capital City! Here the scarf had fallen off in places; the abatis had been wrenched out for firewood; even the solid log platforms, where late the great guns stood on tiptoe, had yielded to the farmer's lever, and made, perhaps, joists for his barn, and piles for his bridge. The solid stone portals opening into bomb-proof and magazine, still remained strong and mortised, but down in the battery and dark subterranean quarters the smell was rank, the floor was full of mushrooms; a dog had littered in the innermost powder magazine, and showed her fangs as I held a lighted match before me advancing. Still, the old names and numbers were painted upon the huge doorways beneath the inner parapet: 'Officers quarters, 21,' 'Mess, 12,' 'Cartridge Box, 7.'[18]

The Fort Circle Parks

The fort remained in a constantly deteriorating condition until 1919 when the Commissioners of the District of Columbia pushed Congress to pass a bill that would consolidate the aging forts into a "Fort Circle" system of parks that would ring the growing city of Washington. As envisioned by the Commissioners, the Fort Circle would be a green ring of parks outside the city, owned by the government, and connected by a "Fort Drive" road to allow Washington's citizens to easily escape the confines of the capital. However, the bill allowing for the purchase of the former forts, which had been turned back over to private ownership after the war, failed to pass both the House of Representatives and Senate.[19]

Despite that failure, in 1925, a similar bill passed both the House and Senate, which allowed for the creation of the National Capital Parks Commission (NCPC) to oversee the construction of a Fort Circle of parks similar to that proposed in 1919.[20] The NCPC was authorized to begin purchasing land occupied by the old forts, much of which had been turned over to private ownership following the war. Records indicate that the site of Fort Stanton was purchased for a total of $56,000 in 1926.[21] The duty of purchasing land and constructing the fort parks changed hands several times throughout the 1920s and 1930s, eventually culminating with the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service taking control of the project in the 1940s.[22]

During the Great Depression, crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps embarked on projects to improve and maintain the parks, which were still under the control of District authority at that time. At Fort Stanton, CCC members trimmed trees and cleared brush, and maintained and constructed park buildings.[23] Various non-park buildings were also discussed for the land. The City Department of Education proposed building a school on parkland, while authorities from the local water utility suggested the construction of a water tower would be suitable for the tall hills of the park.[24] The Second World War interrupted these plans, and post-war budget cuts instituted by President Harry S. Truman postponed the construction of the Fort Drive once more. Though land for the parks had mostly been purchased, construction of the ring road connecting them was pushed back again and again. Other projects managed to find funding, however. In 1949, President Truman approved a supplemental appropriation request of $175,000 to construct "a swimming pool and associated facilities" at Fort Stanton Park.[25]

By 1963, when President John F. Kennedy began pushing Congress to finally build the Fort Circle Drive,[26] many in Washington and the National Park Service were openly questioning whether the plan had outgrown its usefulness.[27] After all, by this time, Washington had grown past the ring of forts that had protected it a century earlier, and city surface roads already connected the parks, albeit not in as linear a route as envisioned.[28] The plan to link Fort Stanton Park with other fort parks via a grand drive was quietly dropped in the years that followed.

Continuing use

Not all the land that made up the site of Fort Stanton was converted to public parkland. In 1920, local African-American Catholics constructed Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church on land formerly owned by Dr. J.C. Norwood, a local physician.[29] After the remaining grounds of the fort were purchased in 1925, nearby residents reportedly "walked family cows to Fort Stanton Park to graze before the school bell rang."[30] Today, the church still stands adjacent to the grounds of the park. The Washington D.C. Department of Parks and National Park Service jointly manage the 67 acres (27 ha) of parkland that stand on the site of the fort today. D.C. authorities manage approximately 11 acres (4.5 ha) that contain a recreation center and ball fields, while the National Park Service manages the remaining acreage, which is mostly wooded and contains the remains of forts Stanton and Ricketts. The area also is site to the Anacostia Museum, a Smithsonian Institution facility devoted to the history of African-Americans.[31]

See also

References

- ^ Cultural Tourism DC. "Fort Stanton and the Washington Overlook" Archived October 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Culturaltourismdc.org. Accessed January 6, 2009.

- ^ J.G. Barnard and W.F. Barry, "Report of the Engineer and Artillery Operations of the Army of the Potomac from Its Organization to the Close of the Peninsular Campaign," (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1863), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1941), pp. 101–110.

- ^ U.S., War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 Volumes (Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office, 1880–1901) I, Volume 5, p. 11.

- ^ Official Records I, 19, Part 2 (serial 28), pp. 391–93

- ^ Official Records I, Volume 5, 11, pp. 678–84

- ^ Official Records I, Volume 5, 11, p. 681

- ^ Official Records I, 21 (serial. 31), pp. 915–16

- ^ Official Records I, 21 (serial. 31), p. 915

- ^ Engineer Bureau, War Department. "Military Map of NE Virginia and the Washington Defenses", Library of Congress Department of Maps. Republished on Wikipedia. Accessed January 6, 2009.

- ^ Official Records I, 21 (serial. 31), 916

- ^ Official Records I, 26, Part 2 (Serial 68), pp. 893–97

- ^ Official Records I, 37, Part 2 (serial 71), pp. 492–95

- ^ Official Records I, 43, Part 2 (serial 91), pp. 280–82.

- ^ Official Records, (Serial 97) Series I, Volume XLVI, Part 3, p. 1130.

- ^ Engineer Orders and Circulars, Orders, Issuances, 1811–1941, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Record Group 77, A2232, B.S. Alexander to Richard Delafield, July 10, 1865 Letters Received, 1826-66

- ^ Army and Navy Journal, 3 (March 24, 1866), p. 486

- ^ George Alfred Townsend, Washington, Outside and Inside. A Picture and A Narrative of the Origin, Growth, Excellences, Abuses, Beauties, and Personages of Our Governing City (Hartford, CT: James Betts & Co., 1873), p. 221.

- ^ Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States ... 66th Congress, 1st Session (Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office, 1919), p. 594

- ^ "Linking of Forts Embodied in Plan," The Evening Star, December 4, 1925

- ^ Record Group 328, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives, General Records, Planting Files, 1924-67, 545-100, Fort Drive, #2, T.C. Jeffers, Landscape Architect, "THE FORT DRIVE, A Chronological History of the More Important Actions and Events Relating Thereto," Feb. 7, 1947.

- ^ National Capital Park and Planning Commission." In H.S. Wagner and Charles G. Sauers, Study of the Organization of the National Capital Parks (Washington, DC: The National Park Service, National Capital Parks, 1939), p. 40

- ^ Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives, Records of the Branch of Recreation, Land Protection, and State Cooperation, Narrative Reports Concerning ECW (CCC) Projects in NPS Areas, 1933-35, District of Columbia, Boxes 11, National Capital Parks, Narrative Report covering Fifth Enrollment Period, ECW Camp N.A. #1, Washington, DC, Apr-Oct 1935

- ^ Record Group 66, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives, Entry 17, Project Files, 1910-52, Forts, Fort Stanton

- ^ House Executive Document No. 361, 81st Congress, 1st Session, "Supplemental Estimate of Appropriation for the Department of the Interior," October 11, 1949.

- ^ Martha Strayer, "JFK Settles Battle Over Ft. Drive," Washington Daily News, May 28, 1963.

- ^ National Capital Planning Commission, Fort Park System: A Re-evaluation Study of Fort Drive, Washington, D.C. April 1965 By Fred W. Tuemmler and Associates, College Park, Maryland (Washington, DC: National Capital Planning Commission, 1965), pp. 3–9

- ^ "Fort Sites Eyed for Future Use," The Washington Post, Friday, October 2, 1964.

- ^ Louise Daniel Hutchinson, The Anacostia Story: 1608–1930 (Washington, DC: Published for the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum of the Smithsonian Institution by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977), p. 126

- ^ Louise Daniel Hutchinson, The Anacostia Story: 1608–1930 (Washington, DC: Published for the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum of the Smithsonian Institution by the Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977), p. 129

- ^ CapitalSpace. "Fort Circle Parks: Fort Stanton" (PDF p. 4) May 20, 2008. Accessed January 6, 2009.