Contents

George Henry Corliss (June 2, 1817 – February 21, 1888) was an American mechanical engineer and inventor, who developed the Corliss steam engine, which was a great improvement over any other stationary steam engine of its time. The Corliss engine is widely considered one of the more notable engineering achievements of the 19th century. It provided a reliable, efficient source of industrial power, enabling the expansion of new factories to areas which did not readily possess reliable or abundant water power.[1] Corliss gained international acclaim for his achievements during the late 19th century and is perhaps best known for the Centennial Engine, which was the centerpiece of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Early life

George Henry Corliss was born June 2, 1817, the second child of Dr. Hiram and Susan (Sheldon) Corliss, at Easton, New York, near the Vermont border.[2] The son of a physician, he attended local schools until age 14, when he began working in a general store in the town of Greenwich, New York. In 1834 he entered the academy at Castleton, Vermont, and graduated in 1838.

Corliss displayed early signs of his mechanical abilities in 1837, after a flood washed away a bridge over the Batten Kill in Greenwich. He organized other local builders in erection of a replacement structure.[3] After graduating from Castleton in 1838, he established his own general store in town of Greenwich where he remained for three years. In January 1839 he married Phebe F. Frost, a native of Canterbury, Connecticut. Together they had two children, Maria and George, Jr.

During this time, Corliss became more interested in mechanical endeavors. Around 1841, he decided to give his whole attention to these new tasks, and in 1842 obtained a patent on a machine for sewing boots, shoes and heavy leather.[3]

Corliss moved to Providence, Rhode Island, in 1844 with hopes of finding funding to perfect his sewing machine. In Providence, he found work in the shop of Fairbanks, Bancroft & Company as a draftsman. However, he soon abandoned work on sewing machines to focus on a new endeavor, improving the stationary steam engine, which at the time was an innefficient or supplemental alternative to water power.

Career

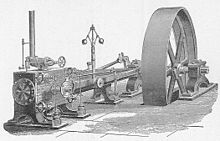

In 1848, Corliss entered into a partnership with John Barstow and E.J. Nightingale under the name Corliss, Nightingale & Company. During the same year, the company built the first engine utilizing Corliss' improvements, which except for various technical improvements later on, was essentially the Corliss steam engine of years later. Corliss and his associates erected a new factory at the junction of Charles Street and the railroad in Providence, where the company would expand greatly in the years to follow. By the time of Corliss' death in 1888, the plant would cover about 5 acres (2 ha) and the company would employ over 1,000 people.

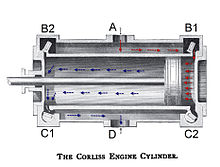

On March 10, 1849, Corliss was granted US Patent #6162 for his valve gear. In 1856 the Corliss Steam Engine Company was incorporated with George Corliss as president, and his younger brother, William, as treasurer.

By 1859, Corliss engines were being exported to Scotland for use in cotton mills. By 1864, valves for the engines were being made at B. Hick and Son, Bolton, England. Corliss directed both the business and research sides of this company, and over the years invented many assembly line improvements such as a bevel-gear cutter.[4] Europe eventually became a great purchaser of the Corliss engine and it was copied by the engine builders who placed upon their imitations the name of the American builder.

The dramatic improvement in fuel efficiency of the Corliss engine was a major selling point to manufacturers, particularly during the early years. Similar to other engine makers of the day, the Corliss Steam Engine Company often negotiated the selling price of their machines on the projected savings in coal.[5]

Corliss' first wife Phebe died on March 5, 1859. In December, 1866, he married Emily Shaw.

The Corliss Steam Engine Company supplied the United States government with machinery during the Civil War. When Monitor was being constructed in 1861, it was found a large ring must be made, upon which the turret of Monitor would revolve, and the Corliss Engine Works was one of the very few plants in the country with the necessary machinery to 'turn' up the large ring. When Corliss found out what the tooling was for, he put aside other business and worked his plant day and night to get this important ring completed and on time and delivered to New York.[citation needed]

By the late 1860s, Corliss began to be recognized internationally for his accomplishments. At the 1867 World's Fair held at Paris, he won the first prize in a competition of the one hundred most famous engine builders in the world. One of its commissioners to the exposition, John Scott Russell, proclaimed of the Corliss valve gear, "A mechanism as beautiful as the human hand. It releases or retains its grasp on the feeding valve, and gives a greater or less dose of steam in nice proportion to each varying want. The American engine of Corliss everywhere tells of wise forethought, judicious proportions and execution and exquisite contrivance."

On January 11, 1870, one hundred years after James Watt patented his first steam engine, Corliss was awarded the Rumford Prize by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It was on this occasion Dr. Asa Gray, the president of the academy, remarked, "No invention since Watt's time has so enhanced the efficiency of the steam engine as this for which the Rumford medal is now presented."

Centennial Exposition

In 1872 the State of Rhode Island appointed Corliss its commissioner to take charge of the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, and he was chosen one of the executive committee appointed to look after the preliminaries. Upon the great task of arranging the exposition, he worked with his usual indefatigable energy and it was his suggestion that the Centennial Board of Finance be organized, a body which had no little to do with the insurance of the financial success of the exhibition.

It was also in his own department as engineer that Corliss contributed largely to the success of the great fair, and it was he that supplied, after the plans of all other competitors proved inadequate, the great fourteen hundred horsepower engine which supplied the power used in Machinery Hall.[6]

This engine, unequaled in size at that time, was installed by Corliss at a cost of one hundred thousand dollars to himself and without additional expenditure to the exposition. The great engine was afterwards used to operate the Pullman Car Works at Chicago until 1910, when it was sold for scrap.[7]

Late career and legacy

Corliss was also active within the community. He was elected three consecutive times to the Rhode Island General Assembly as the Representative from North Providence, his term of service including the three years 1868-69-70. In 1876 he was chosen presidential elector, casting his vote for President Hayes. In the matter of his religious belief he was a Congregationalist. He attended Central Congregational Church in Providence until he joined the Charles Street Church at its founding in 1865. He was keenly interested in the cause of religion and gave liberally both to his own and to other churches.

Corliss' 1849 patent expired in 1870 after it was extended by U.S. Patent reissue 200 on May 13, 1851, and U.S. Patent reissues 758 and 763 on July 12, 1859. After 1870, numerous other companies began to manufacture Corliss engines. Among them, the William A. Harris Steam Engine Company,[8] the Worthington Pump and Machinery Company, and the E.P. Allis Company, which eventually became Allis-Chalmers. In general, these machines were referred to as "Corliss" engines regardless of who made them. The "Corliss-type" engine became particularly popular in Europe. Amusingly, Corliss received the Grand Diploma of Honor by the Vienna Exposition at Vienna in 1873, although he was not even an exhibitor.

Another honor, perhaps the greatest of all was given to him by the Institute of France by public proclamation, March 10, 1879, of the Montyon prize for the year 1878, the most coveted prize for mechanical achievement awarded in Europe. He received this honor by a peculiar coincidence, on the thirtieth anniversary of the granting of his first patent. In 1886, the King of Belgium made Corliss an officer in the Order of Leopold.[9]

Despite the competition, Corliss would continue to remain active within his company, directing changes to his basic design as market or customer needs dictated.[10]

Corliss died on February 21, 1888, at the age of 70. He is buried at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, with his second wife Emily.

The Corliss Steam Engine Company was purchased by the International Power Company in 1900. In 1905 it was purchased by the American and British Manufacturing Company. In 1925 the company merged into Franklin Machine Company.

The house he built in 1875 on the east side of Providence, is now known as the Corliss-Brackett House and is part of Brown University. Corliss Street in Providence, located near the former site of the Corliss factory, is also named in his honor, as is Corliss High School in Chicago.

Corliss was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.[11]

See also

References

- ^ A GENERAL PURPOSE TECHNOLOGY AT WORK: THE CORLISS STEAM ENGINE IN THE LATE 19TH CENTURY US, Nathan Rosenberg and Manuel Trajtenberg, September 2001.

- ^ History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, NY: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1920:

- ^ a b Goddard, Dwight (May 5, 2019). "Eminent engineers: brief biographies of thirty-two of the inventors and engineers who did most to further mechanical progress". The Derry-Collard company – via Google Books.

- ^ "George Henry Corliss Biography (1817-1888)". www.madehow.com.

- ^ Eminent Engineers, p. 116.

- ^ "What If the World Ran on Steam - The Henry Ford". www.thehenryford.org. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ "Some Engines!". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ^ "William A. Harris Steam Engine Co. – New England Wireless & Steam Museum".

- ^ Eminent Engineers, p. 121

- ^ Eminent Engineers, p. 115

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame bio". Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

External links

![]() Media related to George Henry Corliss at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Henry Corliss at Wikimedia Commons