Lao (Lao: ພາສາລາວ, [pʰáː sǎː láːw]), sometimes referred to as Laotian, is the official language of Laos and a significant language in the Isan region of northeastern Thailand, where it is usually referred to as the Isan language. Spoken by over 3 million people in Laos and 3.2 million in all countries, it serves as a vital link in the cultural and social fabric of these areas. It is written in the Lao script, an abugida that evolved from ancient Tai scripts.[3]

Lao is a tonal language, where the pitch or tone of a word can alter its meaning, and is analytic, forming sentences through the combination of individual words without inflection. These features, common in Kra-Dai languages, also bear similarities to Sino-Tibetan languages like Chinese or Austroasiatic languages like Vietnamese. Lao's mutual intelligibility with Thai and Isan, fellow Southwestern Tai languages, allows for effective intercommunication among their speakers, despite differences in script and regional variations.[4]

In Laos, Lao is not only the official language but also a lingua franca, bridging the linguistic diversity of a population that speaks many other languages. Its cultural significance is reflected in Laotian literature, media, and traditional arts. The Vientiane dialect has emerged as the de facto standard, though no official standard has been established. Internationally, Lao is spoken among diaspora communities, especially in countries like the United States, France, and Australia, reflecting its global diasporic presence.[5]

Classification

- Kra-Dai

- Hlai languages

- Kam-Sui languages

- Kra languages

- Be language

- Tai languages

- Northern Tai languages

- Central Tai languages

- Southwestern Tai languages

- Northwestern Tai languages

- Chiang Saen languages

- Northern Thai language

- Sukhothai language

- Lao-Phuthai languages

- Tai Yo language

- Phuthai language

- Lao language (PDR Lao, Isan language)

The Lao language falls within the Lao-Phuthai group of languages, including its closest relatives, Phuthai (BGN/PCGN Phouthai) and Tai Yo. Together with Northwestern Tai—which includes Shan, Ahom and most Dai languages of China, the Chiang Saen languages—which include Standard Thai, Khorat Thai, and Tai Lanna—and Southern Tai form the Southwestern branch of Tai languages. Lao (including Isan) and Thai, although they occupy separate groups, are mutually intelligible and were pushed closer through contact and Khmer influence, but all Southwestern Tai languages are mutually intelligible to some degree. The Tai languages also include the languages of the Zhuang, which are split into the Northern and Central branches of the Tai languages. The Tai languages form a major division within the Kra-Dai language family, distantly related to other languages of southern China, such as the Hlai and Be languages of Hainan and the Kra and Kam-Sui languages on the Chinese Mainland and in neighbouring regions of northern Vietnam.[6]

History

Tai migration (8th–12th century)

The ancestors of the Lao people were speakers of Southwestern Tai dialects that migrated from what is now southeastern China, specifically what is now Guangxi and northern Vietnam where the diversity of various Tai languages suggests an Urheimat. The Southwestern Tai languages began to diverge from the Northern and Central branches of the Tai languages, covered mainly by various Zhuang languages, sometime around 112 CE, but likely completed by the sixth century.[7] Due to the influx of Han Chinese soldiers and settlers, the end of the Chinese occupation of Vietnam, the fall of Jiaozhi and turbulence associated with the decline and fall of the Tang dynasty led some of the Tai peoples speaking Southwestern Tai to flee into Southeast Asia, with the small-scale migration mainly taking place between the eighth and twelfth centuries. The Tais split and followed the major river courses, with the ancestral Lao originating in the Tai migrants that followed the Mekong River.[8]

Divergence and convergence

As the Southwestern Tai-speaking peoples diverged, following paths down waterways, their dialects began to diverge into the various languages today, such as the Lao-Phuthai languages that developed along the Mekong River and includes Lao and its Isan sub-variety and the Chiang Saen languages which includes the Central Thai dialect that is the basis of Standard Thai. Despite their close relationship, there were several phonological divergences that drifted the languages apart with time such as the following examples:[9][10][11]

- PSWT *ml > Lao /m/, > Thai /l/

*mlɯn

'slippery'

ມື່ນ

muen

/mɯ̄ːn/

ลื่น

luen

/lɯ̂ːn/

- PSWT *r (initial) > Lao /h/, > Thai /r/

*raːk

'to vomit'

ຮາກ

hak

/hȃːk/

ราก

rak

/râːk/

- PSWT *ɲ > Lao /ɲ/, > Thai /j/

*ɲuŋ

'mosquito'

ຍູງ

nyung

/ɲúːŋ/

ยุง

yung

/jūŋ/

Similar influences and proximity allowed for both languages to converge in many aspects as well. Thai and Lao, although separated, passively influenced each other through centuries of proximity. For instance, the Proto-Southwestern Tai *mlɛːŋ has produced the expected Lao /m/ outcome maeng (ແມງ mèng, /mɛ́ːŋ/) and the expected Thai /l/ outcome laeng (แลง /lɛ̄ːŋ/), although this is only used in Royal Thai or restricted academic usage, with the common form malaeng (แมลง /máʔ lɛ̄ːŋ/), actually an archaic variant. In slang and relaxed speech, Thai also has maeng (แมง /mɛ̄ːŋ/), likely due to influence of Lao.[9]

Thai and Lao also share similar sources of loan words. Aside from many of the deeply embedded Sinitic loan words adopted at various points in the evolution of Southwestern Tai at the periphery of Chinese influence, the Tais in Southeast Asia encountered the Khmer. Khmer loan words dominate all areas and registers of both languages and many are shared between them. Khmer loan words include body parts, urban living, tools, administration and local plants. The Thai, and likely the Lao, were able to make Khmer-style coinages that were later exported back to Khmer.[12] The heavy imprint of Khmer is shown in the genetics of Tai speakers, with samples from Thai and Isan people of Lao descent showing proof of both the Tai migration but also intermarriage and assimilation of local populations. Scholars such as Khanittanan propose that the deep genetic and linguistic impact of the autochthonous Khmer and their language indicates that the earliest days of Ayutthaya had a largely bilingual population.[13] Although evidence and research in Lao is lacking, major Lao cities were known to have been built atop existing Khmer settlements, suggesting assimilation of the locals. Isan and Lao commonly use a Khmer loan not found in Thai, khanong (ຂະໜົງ/ຂນົງ khanông, /kʰáʔ nŏŋ/), 'doorframe', from Khmer khnâng (ខ្នង, /knɑːŋ/), which means 'building', 'foundation' or 'dorsal ridge'.[12][14]

Indic languages also pushed Thai and Lao closer together, particularly Sanskrit and Pali loan words that they share. Many Sanskrit words were adopted via the Khmer language, particularly concerning Indian concepts of astrology, astronomy, ritual, science, kingship, art, music, dance and mythology. New words were historically coined from Sanskrit roots just as European languages, including English, share Greek and Latin roots used for these purposes, such as 'telephone' from Greek roots τῆλε tēle, 'distant' and φωνή phōnē which was introduced in Thai as thorasap (โทรศัพท์, /tʰōː ráʔ sàp/) and spread to Isan as thorasap (ໂທຣະສັບ/ໂທລະສັບ thôrasap, /tʰóː lāʔ sáp/) from Sanskrit dura (दूर, /d̪ura/), 'distant', and śabda (शब्द, /ʃabd̪a/), 'sound'. Indic influences also came via Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism.

The effects of Khmer and Indic vocabulary did not affect all the Tai languages of Southeast Asia equally. The Tai Dam of northern Vietnam were shielded from the influence of the Khmer language and the Indic cultural influences that came with them and remain traditionally a non-Buddhist people. Although the Tai Dam language is a Chiang Saen language, albeit with a lexicon and phonology closer to Lao, the lack of Khmer, Sanskrit and Pali loan words makes the language unintelligible to Thai and Lao speakers.[15]

Lan Xang (1354–1707)

Taking advantage of rapid decline in the Khmer Empire, Phra Chao Fa Ngoum (ຟ້າງູ່ມ fȁː ŋum) defeated the Khmer and united the Tai mueang of what is now Laos and Isan into the mandala kingdom of Lan Xang in 1354. Fa Ngoum was a grandson of the ruler of Muang Xoua (RTGS Mueang Sawa), modern-day Louang Phrabang. Lan Xang was powerful enough to thwart Siamese designs from their base at Sukhothai and later Ayutthaya.[16]

Khmer, and Sanskrit via Khmer, continued to influence the Lao language. Since Fa Ngoum was raised in the Khmer court, married to a Khmer princess and had numerous Khmer officials in his court, a now-extinct speech register known as raxasap (ຣາຊາສັບ /láː sáː sáp/) was developed to address or discuss the king and high-ranking clergy. Khmer and Sanskrit also contributed many belles-lettres as well as numerous technical, academic and cultural vocabulary, thus differentiating the Lao language from the tribal Tai peoples, but pushing the language closer to Thai, which underwent a similar process. The end of the Lao monarchy in 1975 made the Lao raxasap obsolete, but as Thailand retains its monarchy, Thai rachasap is still active.[15]

The 16th century would see the establishment of many of the hallmarks of the contemporary Lao language. Scribes abandoned the use of written Khmer or Lao written in the Khmer alphabet, adopting a simplified, cursive form of the script known as Tai Noi that with a few modifications survives as the Lao script.[17] Lao literature was also given a major boost with the brief union of Lan Xang with Lan Na during the reign of Xay Xétthathirat (ໄຊເສດຖາທິຣາດ /sáj sȅːt tʰăː tʰī lȃːt/) (1546–1551). The libraries of Chiang Mai were copied, introducing the tua tham (BGN/PCGN toua tham) or 'dharma letters' which was essentially the Mon-influenced script of Lan Na but was used in Lao specifically for religious literature.[17] The influence of the related Tai Lan Na language was strengthened after the capitulation of Lan Na to the Burmese, leading many courtiers and people to flee to safety to Lan Xang.

Theravada Buddhism

Lan Xang was religiously diverse, with most of the people practicing Tai folk religion albeit somewhat influenced by local Austroasiatic animism, as well as the Brahmanism and Mahayana Buddhism introduced via the Khmer and Theravada Buddhism which had been adopted and spread by the Mon people. Although Lao belief is that the era of Lan Xang began the period of Theravada Buddhism for the Lao people, it was not until the mid-sixteenth century that the religion had become the dominant religion.[18]

The earliest and continuously used Theravada temple, Vat Vixoun was built in 1513 by King Vixounnarat (ວິຊຸນນະຣາດ) (1500–1521). His successor, Phôthisarat (ໂພທິສະຣາດ) (1520–1550), banned Tai folk religion and destroyed important animist shrines, diminished the role of the royal Brahmins and promoted Theravada Buddhism. Phôthisarat married a princess of Lan Na, increasing contact with the kingdom that had long adopted the religion via contacts with the Mon people, a process that would continue when Phôthisarat's son assumed the thrones of Lan Xang and Lan Na.[19]

With Theravada Buddhism came its liturgical language, Pali, an Indic language derived from the Prakrit. Many Pali terms existed alongside earlier Sanskrit borrowings or were Sanskritized, leading to doublets such as Sanskrit maitri (ໄມຕີ/ໄມຕຣີ /máj tiː/) and Pali metta (ເມດຕາ/ເມຕຕາ /mȇːt taː/), both of which signify 'loving kindness' although the Sanskrit term is more generally used for 'friendship'. The spread of Theravada Buddhism spread literacy, as monks served as teachers, teaching reading and writing as well other basic skills to village boys, and the Tai Noi script was used for personal letters, record-keeping, and signage, as well as to record short stories and the klon (ກອນ /kɔːn/) poetry that were often incorporated into traditional folksongs.[17]

| Pali | Isan | Thai | Lao | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| पुञ्ञ puñña /puɲɲa/ |

บุญ bun /būn/ |

บุญ bun /būn/ |

ບຸນ bun /bùn/ |

'merit' 'virtue' |

| दुक्ख dukkha /d̪ukkʰa/ |

ทุกข์ thuk /tʰūk/ |

ทุกข์ thuk /tʰúk/ |

ທຸກ thouk /tʰūk/ |

'suffering' 'misery' |

| पापकम्म pāpakamma /paːpakamma/ |

บาปกรรม bapkam /bàːp kām/ |

บาปกรรม bapkam /bàːp kām/ |

ບາບກຳ/ບາບກັມ bapkam /bȁːp kàm/ |

'sin' 'transgression' |

| अनुमोदना anumōdanā /ʔanumoːd̪anaː/ |

อนุโมทนา anumothana /ʔǎʔ nūʔ móː tʰāʔ náː/ |

อนุโมทนา anumothana /ʔàʔ núʔ mōː tʰáʔ nāː/ |

ອະນຸໂມທະນາ anoumôthana /ʔáʔ nūʔ móː tʰā náː/ |

'to share rejoicing' |

| सुख sukha /sukʰa/ |

สุข suk /súk/ |

สุข suk /sùk/ |

ສຸກ souk /súk/ |

'health' 'happiness' |

| विज्जा vijja /ʋiɟdʒaː/ |

วิชชา witcha /wīt tɕʰáː/ /wī tɕʰáː/ |

วิชชา witcha /wít tɕʰāː/ |

ວິຊາ visa /ʋī sáː/ |

'knowledge' 'wisdom' |

| चक्कयुग cakkayuga /tʃakkajuga/ |

จักรยาน chakkrayan /tɕǎk káʔ ɲáːn/ |

จักรยาน chakkrayan /tɕàk kràʔ jāːn/ |

ຈັກກະຍານ chakkagnan /tɕák káʔ ɲáːn/ |

'bicycle' |

| धम्म ḍhamma /ɖʱamma/ |

ธรรม tham /tʰám/ |

ธรรม tham /tʰām/ |

ທຳ/ທັມ tham /tʰám/ |

'dharma' 'morals' |

Lao Three Kingdoms period (1713–1893)

Despite the long presence of Lan Xang and Lao settlements along the riverbanks, the Khorat Plateau remained depopulated since the Post-Angkor Period and a long series of droughts during the 13th–15th centuries. The Lao settlements were found only along the banks of the Mekong River and in the wetter northern areas such as Nong Bua Lamphu, Loei, Nong Khai, with most of the population inhabiting the wetter left banks. This began to change when the golden age of Lao prosperity and cultural achievements under King Sourignavôngsa (ສຸຣິຍະວົງສາ /sú lī ɲā ʋóŋ sǎː/) (1637–1694) ended with a successional dispute, with his grandsons, with Siamese intervention, carving out their separate kingdoms in 1707. From its ashes arose the kingdoms of Louang Phrabang, Vientiane and later in 1713, the Champasak. The arid hinterlands, deforested and depopulated after a series of droughts, likely led to the collapse of the Khmer Empire, was only occupied by small groups of Austroasiatic peoples and scattered outposts of Lao mueang in the far north. In 1718, Mueang Suwannaphum (ສຸວັນນະພູມ Muang Suovannaphoum, /sú ʋán nāʔ pʰúːm) in 1718 in what is now Roi Et Province, was founded as an outpost of Champasak, establishing the first major Lao presence and the beginning of the expansion of Lao settlement along the Si (ຊີ /síː/) and Mun (ມູນ) rivers.[citation needed]

The bulk of the Lao, however, settled after 1778 when King Taksin, Siamese king during the Thonburi Period (1767–1782) conquered Champasak and Vientiane and raided Phuan areas for slaves, seizing the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang (although the latter was eventually returned) and forcing some of the Lao across the river to settle in Isan. Louang Phrabang was spared most of the destruction by submitting to Siamese overlordship.[20] Although the kingdoms remained nominally autonomous, the Siamese demanded tribute and taxes, kept members of the respective royal houses as hostages to ensure loyalty and required the three Lao kings to come to the capital several times a year to hold an audience with the Siamese king. When the kingdoms revolted, the Siamese armies retaliated by rounding up entire villages, tattooing them to mark them as slaves and forced to settle what is now Isan, forced to serve as soldiers or manpower in corvée projects to build roads, to grow food, build canals, or serve as domestics. The greatest population transfer occurred after the Laotian Rebellion by Chao Anouvông (ອານຸວົງ/ອານຸວົງສ໌, /ʔàː nū ʋóŋ/) in 1828 which led to the death of Anouvông and most of his family. The Siamese abducted nearly the entire population of Vientiane and its surrounding area and forced them to the right bank. Continued raids of people continued until the end of the nineteenth century.[21]

In addition to forced transfers, many Lao were encouraged to settle in Isan, with some disillusioned princes granted lofty titles in exchange for loyalty and taxation, robbing the Lao kings of taxation and wealth as well as what little nominal authority they had left. This greatly expanded the Lao population of Isan and caused assimilation of the local peoples into the mix, a process that is occurring on a smaller scale even now. Siamese intervention paradoxically strengthened the Lao character of the region as the Siamese left the Lao areas alone as long as they continued to produce rice and continued to pay tribute. Direct Siamese rule did not extend past Nakhon Ratchasima, and the Lao mueang, whether paying their tribute directly to Bangkok or the remaining Lao kings and princes, were still nominally part of the separate kingdoms. Temples built in what is now Isan still featured the Tai Noi script on its murals and although Siam would intervene in some matters, daily administration was still left to the remaining kings and various Lao princes that served as governors of the larger mueang. The result of the population movements re-centered the Lao world to the right bank, as today, if Isan and Lao speakers are counted together, Isan speakers form 80 percent of the Lao-speaking population.[citation needed]

French Laos (1893–1953)

During French rule, missing words for new technologies and political realities were borrowed from French or Vietnamese, repurposed from old Lao vocabulary as well as coined from Sanskrit. These Sanskrit-derived neologisms were generally the same, although not always, as those that developed in Thai.[22][23]

Whilst previously written in a mixture of etymological and phonetical spellings, depending on audience or author, Lao underwent several reforms that moved the language towards a purely phonetical spelling. During the restoration of the king of Louang Phabang as King of Laos under the last years of French rule in Laos, the government standardized the spelling of the Lao language, with movement towards a phonetical spelling with preservation of a semi-etymological spelling for Pali, Sanskrit and French loan words and the addition of archaic letters for words of Pali and Sanskrit origin concerning Indic culture and Buddhism.

Independence and Communist rule (1953–present)

Spelling reforms under the communist rule of Laos in 1975 were more radical, with the complete abolition of semi-etymological spelling in favor of phonetical spelling, with the removal of silent letters, removal of special letters for Indic loan words, all vowels being written out implicitly and even the elimination or replacement of the letter 'ຣ' /r/ (but usually pronounced /l/) in official publications, although older people and many in the Lao diaspora continue to use some of the older spelling conventions.[24]

Dialects

The standard written Lao based on the speech of Vientiane has leveled many lexical differences between dialects found in Laos, and although spoken regional variations remain strong, speakers will adjust to it in formal situations and in dealings with outsiders.[25]

| Dialect | Lao Provinces | Thai Provinces |

| Vientiane Lao | Vientiane, Vientiane Prefecture, Bolikhamxay and southern Xaisômboun | Nong Khai, Nong Bua Lamphu, Chaiyaphum, Udon Thani, portions of Yasothon, Bueng Kan, Loei and Khon Kaen (Khon Chaen) |

| Northern Lao Louang Phrabang Lao |

Louang Phrabang, Xaignbouli, Oudômxay, Phôngsali, Bokèo, and Louang Namtha, portions of Houaphan | Loei, portions of Udon Thani, Khon Kaen(Khon Chaen), also Phitsanulok, Phetchabun (Phetsabun) and Uttaradit (outside Isan) |

| Northeastern Lao Phuan (Phouan) Lao |

Xiangkhouang, portions of Houaphan and Xaisômboun | Scattered in isolated villages of Chaiyaphum, Sakon Nakhon, Udon Thani, Bueng Kan, Nong Khai and Loei[a] |

| Central Lao (ລາວກາງ) | Khammouan and portions of Bolikhamxay and Savannakhét | Mukdahan, Sakon Nakhon, Nakhon Phanom, Mukdahan; portions of Nong Khai and Bueng Kan |

| Southern Lao | Champasak, Saravan, Xékong, Attapeu, portions of Savannakhét | Ubon Ratchathani (Ubon Ratsathani), Amnat Charoen, portions of Si Sa Ket, Surin, Nakhon Ratchasima (Nakhon Ratsasima), and Yasothon[b] |

| Western Lao (Standard Isan) | * Not found in Laos | Kalasin, Roi Et (Hoi Et), Maha Sarakham, portions of Khon Kaen (Khon Chaen), Chaiyaphum (Sainyaphum), and Nakhon Ratchasima (Nakhon Ratsasima) |

Vientiane Lao dialect

In Laos, the written language has been mainly based on Vientiane Lao for centuries after the capital of Lan Xang was moved in 1560. The speech of the old élite families was cultivated into Standard Lao as emulated by television and radio broadcasts from the capital as well as taught to foreign students of Lao. The speech of the Isan city of Nong Khai, which sits on the opposite bank of the Mekong, is almost indistinguishable in tone and accent from the speech of Vientiane. Vientiane Lao predominates in Vientiane City, the surrounding Vientiane Province and portions of Bolikhamxai and some areas of Xaisômboun.

In Isan, Vientiane Lao is the primary form of Isan spoken in the northern third of the region which was long settled since the days of Lan Xang and was ruled as part of the Kingdom of Vientiane, including most of Nong Khai, Nong Bua Lamphu, eastern Loei and portions of Saiyaphum and Bueng Kan. As a result of the Lao rebellion of 1826 the Tai Wiang (ໄທວຽງ), /tʰáj ʋíːəŋ/), 'Vientiane people' of the city and surrounding parts of the kingdom, were rounded up by Siamese armies and forced to the right bank, greatly boosting the Lao population of what is now Isan. The Tai Wiang strengthened numbers in the northern third, where Vientiane Lao was traditionally spoken, but were scattered across the Isan region overall, with heavier concentrations in Yasothon, Khon Kaen, and Hoi Et provinces. This likely had a leveling effect on the Lao language as spoken in Isan, as most Isan speakers regardless of speech variety are prone to using /ʋ/ as opposed to /w/ and the informal conversion of syllable-initial /k/ to /tɕ/ in relaxed, informal speech, which in Laos, is particularly characteristic of Vientiane speech. For example, the word kaem (ແກ້ມ kèm, /kɛ̂ːm/), 'cheek', is often pronounced *chaem (*ແຈ້ມ chèm, */tɕɛ̂ːm/).

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low-Rising | Middle | Low-Falling (glottalized) | Low-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Middle | Low-Rising | Middle | High-Falling (glottalized) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Low | High-Rising | Middle | High-Falling | High-Falling | Middle (high) |

Northern Lao (Louang Phrabang) dialect

Northern Lao is a very distinct dialect, exhibiting several features and lexical differences quite apart from other Lao dialects except Northeastern Lao (Phuan). Even though it borders the Vientiane Lao dialect region, there is a sharp boundary that divides them. The dialect shares many similarities with Tai Lanna and is classified accordingly as a Chiang Saen language by Ethnologue.[6] The dialect is not common in Isan, restricted to western portions of Loei and pockets of villages spread throughout Udon Thani provinces. The Isan people of Phitsanulok and Uttaradit provinces, particularly the narrow strip hugging the shore of the Mekong and bordering Loei, outside of Isan are generally speakers of Northern Lao. In Laos, it is the primary dialect spoken in Louang Phrabang and Xaignabouli provinces. In the other northern Laotian provinces of Oudômxai, Houaphan, Louang Namtha and Phôngsali, native Lao speakers are a small minority in the major market towns but Northern Lao, highly influenced by the local languages, is spoken as the lingua franca across ethnic groups of the area.[27]

Northern Lao, specifically the speech of the city of Louang Phrabang was originally the prestigious variety of the language with the city serving as the capital of Lan Xang for the first half of its existence, with the kings of the city made kings of all of Laos by the French. Although the language lost its prestige to Vientiane Lao, Northern Lao is important for its history, as many of the earliest Lao literary works were composed in the dialect, and it served, in a refined form, as the royal speech of the Laotian kings until 1975 when the monarchy was abolished. Louang Phrabang remains the largest city in the northern region of Laos, serving as an important center of trade and communication with the surrounding areas.

Despite the proximity to speakers of Vientiane Lao, Northern Lao is quite distinct. Unlike other Lao dialects with six tones, Northern Lao speakers use only five. Due to the distinctive high-pitch, high-falling tone on words with live syllables starting with low-class consonants, the dialect is said to sound softer, sweeter and more effeminate than other Lao dialects, likely aided by the slower speed of speaking.[28] Similar in tonal structure and quality to Tai Lanna, likely facilitated by the immigration of Lanna people to Louang Phrabang after Chiang Mai's fall to the Burmese in 1551, the dialect is classified apart from other Lao dialects as Chiang Saen language by Ethnologue.[6] Northern Lao also resisted the merger of Proto-Tai */aɰ/ and */aj/ that occurred in all other Lao dialects, except Northeastern Lao. This affects the twenty or so words represented by Thai 'ใ◌' and Lao 'ໃ◌', which preserve /aɰ/ in Northern Lao. This vowel has become /aj/, similar to Thai 'ไ◌' and Lao 'ໄ◌' which is also /aj/. Northern Lao also contains numerous terms not familiar to other Lao speakers.[29]

| Source | Thai | Isan | Vientiane Lao | Northern Lao | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| */ʰmɤːl/ | ใหม่ mai /màj/ |

ใหม่ mai /māj/ |

ໃຫມ່ mai /māj/ |

ໃຫມ່ *mau /māɯ/ |

'new' |

| */haɰ/ | ให้ hai /hâj/ |

ให้ hai /hȁj/ |

ໃຫ້ hai /hȁj/ |

ໃຫ້ hau /hȁɯ/ |

'to give' |

| */cɤɰ/ | ใจ chai /tɕāj/ |

ใจ chai /tɕāj/ |

ໃຈ chai /tɕàj/ |

ໃຈ *chau /tɕaɯ/ |

'heart' |

| */C̥.daɰ/ | ใน nai /nāj/ |

ใน nai /náj/ |

ໃນ nai /náj/ |

ໃນ *nau /na᷇ɯ/ |

'inside' |

| */mwaj/ | ไม้ mai /máːj/ |

ไม้ mai /mâj/ |

ໄມ້ mai /mâj/ |

ໄມ້ mai /ma᷇j/ |

'wood'. 'tree' |

| */wɤj/ | ไฟ fai /fāj/ |

ไฟ fai /fáj/ |

ໄຟ fai /fáj/ |

ໄຟ fai /fa᷇j/ |

'fire' |

| Thai | Isan | Vientiane Lao | Northern Lao | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| เล่น len /lên/ |

หลิ้น lin /lȉn/ |

ຫລິ້ນ/ຫຼິ້ນ lin /lȉn/ |

ເອວ (เอว) eo /ʔeːw/ |

'to joke', 'to play' |

| ลิง ling /liŋ/ |

ลีง ling /líːŋ/ |

ລີງ ling /líːŋ/ |

ລິງ (ลิง) ling /lîŋ/ |

'monkey' |

| ขนมปัง khanom pang /kʰàʔ nǒm pāŋ/ |

เข้าจี่ ขนมปัง khao chi khanom pang /kʰȁo tɕíː/ /kʰáʔ nŏm pāŋ/ |

ເຂົ້າຈີ່ khao chi /kʰȁo tɕīː/ |

ຂມົນປັງ (ขนมปัง) khanôm pang /kʰa᷇ʔ nǒm pâŋ/ |

'bread' |

| ห่อ ho /hɔ̀ː/ |

ห่อ ho /hɔ̄ː/ |

ຫໍ່ ho /hɔ̄ː/ |

ຄູ່ (คู่) khou /kʰu᷇ː/ |

'parcel', 'package' |

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Mid-Falling Rising | Middle | High-Falling (glottalized) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Middle | Low-Rising | Middle | Mid-Rising (glottalized) | High-Falling | Mid-Rising |

| Low | Low-Rising | Middle | Mid-Rising | Mid-Rising | Middle |

Northeastern Lao dialect (Tai Phouan)

The Phuan language is a Chiang Saen (Thai) language rather than part of the Lao–Phutai languages, but it is considered a Lao dialect in Laos. As a Tai language of northern Southeast Asia, it shares many similarities with Tai Dam and Tai Lan Na. In contrast to other minority languages of Isan, it is not losing ground to the Thai or Isan language in Isan.[6]

Central Lao

Central Lao represents a transitional variety, with northern varieties closer to Vientiane Lao and southern varieties, roughly south of the confluence of the Xé Noi river with the Mekong, the speech varieties begin to approach Southern Lao. Some linguists, such as Hartmann, place Vientiane Lao and Central Lao together as a singular dialect region.[31] More Vientiane-like speech predominates in the Isan provinces of Bueng Kan, Sakon Nakhon, most of Nakhon Phanom and some areas of Nong Khai provinces and on the Laotian side, portions of eastern and southern Bolikhamxai and Khammouan provinces. More Southern Lao features are found in the speech of Mukdahan and southern Nakhon Phanom provinces of Thailand and Savannakhét Province of Laos.

Nevertheless, the tones of the southern Central varieties, such as spoken in Mukdahan, Thailand and Savannakhét, Laos have a tonal structure more akin to Vientiane Lao, sharing certain splits and contours. These areas do, however, exhibit some Southern features of their lexicon, such as the common use of se (ເຊ xé, /sêː/), 'river', which is typical of Southern Lao as opposed to nam (ນ້ຳ, /nȃːm/), which is the more common word and also signifies 'water' in general. Mukdahan-Savannakhét area speakers also understand mae thao (ແມ່ເຖົ້າ, /mɛ́ː tʰȁw/) as a respectful term for an 'old lady' (as opposed to Vientiane 'mother-in-law') and use pen sang (ເປັນສັງ, /pȅn sȁŋ/) instead of Vientiane pen yang (ເປັນຫຍັງ, /pen ɲăŋ/), 'what's wrong?', as is typical of Southern Lao.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | Rising | Middle | Low-Falling | Rising | Low-Falling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle | High-Falling | Middle | Rising-Falling | Rising | Low-Falling |

| Low | High-Falling | Middle | Rising-Falling | High-Falling | Middle |

Southern Lao

Southern Lao is spoken along the southern third of Isan and Laos. This region covers the Thai provinces of Surin, Buriram and Sisaket, where a large minority of speakers are Khmer people speaking the archaic northern variety of Khmer and another Austroasiatic people, the Kuy people, use Southern Lao as a second language to engage with their Isan neighbors. It is also spoken in Ubon Ratsathani, Amnat Charoen and portions of Yasothon and Nakhon Ratsasima. In Laos, it is the primary dialect of Champasak, Salavan, Attapeu and Xékong provinces. There are also small pockets of speakers located in Steung Treng Province, Cambodia or Siang Taeng (ຊຽງແຕງ, /síaːŋ tɛːŋ/), particularly near the Mekong River close to the Laotian border. Many of the areas where Southern Lao is spoken were formerly part of the Kingdom of Champasak, one of the three successor states to the Kingdom of Lan Xang, prior to the division of the Lao-speaking world between France and Siam.

Compared to other Isan and Lao dialects, Southern Lao has low tones in syllables that begin with high- or middle-class consonants and have long vowels. High- and middle-class consonants marked with the mai tho tone mark are low and low-falling, respectively, but in these cases are pronounced with very strong glottalization, which can be described as 'creaky'. Combined with the somewhat faster manner of speaking and reduced tendency to soften consonants at the end of words, Southern Lao sounds very rough and harsh to speakers of other dialects. Many of these features, such as the faster speaking pace and glottalization may be influences from Austroasiatic languages as most of the region was inhabited by the Khmer, Kuy and various other Austroasiatic peoples until the eighteenth century when the Lao began to settle and even now, Khmer speakers comprise half the population of Surin and roughly a quarter each of the populations of Sisaket and Buriram provinces.[28]

Specific dialectal words include don (ດອນ, /dɔ̀ːn/), 'riparian island', se (ເຊ xé, /sȅː/)) and many of the words used in Savannakhét that are more typical of Southern Lao such as mae thao (ແມ່ເຖົ້າ, /mɛ́ː tʰȁo/) as a respectful term for an 'old lady' (as opposed to Vientiane 'mother-in-law') and use pen sang (ເປັນສັງ, /pȅn sȁŋ/) instead of Vientiane pen yang (ເປັນຫຍັງ pén gnang, /pen ɲăŋ/), 'what's wrong?'. Possibly as a result of historical Khmer influence and current influences from Thai, Southern dialects tend to pronounce some words with initial Proto-Southwestern Tai */r/ as either the rhotic tap /ɾ/ or a strongly velarized /ɬ/ which is confused with /d/ by speakers of other Lao dialects which have /h/. For example, Vientiane Lao hap (ຮັບ, /hāp/), 'to receive', and honghaem (ໂຮງແຮມ hônghèm, /hóːŋ hɛ́ːm/) are pronounced as lap (ລັບ, /ɾàp/) and honglaem (ໂຮງແລມ hônglèm, /hɔ̏ːŋ ɾɛ̏ːm/), respectively but may sound like *dap and *hongdaem (hông dèm) to other Lao, but are really a strongly velarized /ɬ/ or a rhotic tap /ɾ/.[33] Southerners also tend to use chak (ຈັກ, /tɕa᷇k/) to mean 'to know someone' as opposed to hu chak (ຮູ້ຈັກ hou chak, /hȗː tɕák/) used in all other dialects.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | High-Rising | Lower-Middle | Low (glottalized) | Low | High-Rising |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle | Middle | Lower-Middle | Low-Falling (glottalized) | Low | High-Rising |

| Low | Mid-Falling | Lower-Middle | Low-Falling | Low-Falling | Lower-Middle (short) |

Western Lao

Western Lao (Standard Isan) does not occur in Laos but is the primary dialect of Khon Kaen, Kalasin, Hoi Et, and Maha Sarakham in Isan, Thailand. It is also spoken in much of Saiyaphum and portions of Nakhon Ratsasima.

| Tone Class | Inherent Tone | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) | Long Vowel | Short Vowel |

| High | Low-Rising | Middle | Low | Low | Low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle | Rising-Mid-Falling | Middle | Mid-Falling | Low | Low |

| Low | Rising-High-Falling | Low | High-Falling | Middle | Middle |

Vocabulary

The Lao language consists primarily of native Lao words. Because of Buddhism, however, Pali has contributed numerous terms, especially relating to religion and in conversation with members of the sangha. Due to their proximity, Lao has influenced the Khmer and Thai languages and vice versa.

Formal writing has a larger number of loanwords, especially Pali and Sanskrit, much as Latin and Greek have influenced European languages. For politeness, pronouns (and more formal pronouns) are used, plus ending statements with ແດ່ (dǣ [dɛː]) or ເດີ້ (dœ̄ [dɤ̂ː]). Negative statements are made more polite by ending with ດອກ (dǭk [dɔ᷆ːk]). The following are formal register examples.

- ຂອບໃຈຫຼາຍໆເດີ້ (khǭp chai lāi lāi dœ̄, [kʰɔ᷆ːp t͡ɕàj lǎːj lǎːj dɤ̂ː]) Thank you very much.

- ຂ້ານ້ອຍເຮັດບໍ່ໄດ້ດອກ (khānǭi het bǭ dai dǭk, [kʰa᷆ːnɔ̂ːj hēt bɔ̄ː dâj dɔ᷆ːk]) I cannot.

- ໄຂປະຕູໃຫ້ແດ່ (khai pa tū hai dǣ, [kʰǎj pa.tùː ha᷆j dɛ̄ː ]) Open the door, please.

French loanwords

After the division of the Lao-speaking world in 1893, French would serve as the administrative language of the French Protectorate of Laos, carved from the Lao lands of the left bank, for sixty years until 1953 when Laos achieved full independence.[36] The close relationship of the Lao monarchy with France continued the promotion and spread of French until the end of the Laotian Civil War when the monarchy was removed and the privileged position of French began its decline. Many of the initial borrowings for terms from Western culture were imported via French. For instance, Lao uses xangtimèt (ຊັງຕີແມດ /sáŋ tìː mɛ́ːt/) in an approximation of French centimètre (/sɑ̃ ti mɛtʀ/). Lao people also tend to use French forms of geographic place names, thus the Republic of Guinea is kiné (/ກີເນ/ /kìː néː/) from French Guinée (/gi ne/).

Although English has mostly surpassed French as the preferred foreign language of international diplomacy and higher education since the country began opening up to foreign investment in the 1990s, the position of French is stronger in Laos than in Cambodia and Vietnam. Since 1972, Laos has been associated with La Francophonie, achieving full-member status in 1992. Many of the royalists and high-ranking families of Laos left Laos in the wake of the end of the Laotian Civil War for France, but as of 2010, it was estimated that 173,800 people, or three percent of the population, were fluent in French and French is studied by 35% of the population as a second language as a required subject and many courses in engineering, medicine, law, administration and other advanced studies are only available in French.[36]

Laos maintains the French-language weekly Le Rénovateur, but French-language content is sometimes seen alongside English in publications in older issues of Khaosane Phathét Lao News and sporadically on television ad radio.[37] French still appears on signage, is the language of major civil engineering projects and is the language of the élite, especially the older generations that received secondary and tertiary education in French-medium schools or studied in France. France maintains a large Lao diaspora and some of the very well-to-do still send their children to France for study. The result of this long-standing French influence is the use of hundreds of loan words of French origin in the Lao language of Laos—although many are old-fashioned and somewhat obsolete or co-exist alongside more predominant native usages. They may be contrasted with the neighbouring languages in Thailand, which borrowed from English instead of French.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | French | Lao alternate |

Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| เนกไท nek thai /né(ː)k tʰáj/ |

เนกไท nek thai /nê(ː)k tʰāj, -tʰáj/ |

ກາລະວັດ/ກາຣະວັດ (*การะวัด) karavat /kàː lāʔ ʋāt/ |

cravate /kʁa vat/ |

'necktie' | |

| โฮงภาพยนตร์ hong phapphayon /hóːŋ pʰȃːp pʰāʔ ɲón/ |

โรงภาพยนตร์ rong phapphayon /rōːŋ pʰȃːp pʰáʔ jōn/ |

ໂຮງຊີເນມາ (*โฮงซิเนมา) hông xinéma /hóːŋ sīʔ nɛ´ː máː/ |

cinéma /si ne ma/ |

ໂຮງຫນັງ hông nang |

'cinema', 'movie theater' (US) |

| พจนานุกรม photchananukrom /pʰōt tɕáʔ náː nūʔ kom/ |

พจนานุกรม photchananukrom /pʰót tɕàʔ nāː núʔ krōm/ |

ດີຊອນແນ/ດີຊອນແນຣ໌ (*ดิซอนแนร์) dixonnè /diː sɔ́ːn nɛ́ː/ |

dictionnaire /dik sjɔ nɛʁ/ |

ພົດຈະນານຸກົມ phôtchananoukôm |

'dictionary' |

| แอฟริกา aepfrika /ʔɛ̏ːp fīʔ kaː/ |

แอฟริกา aepfrika /ʔɛ́ːp fríʔ kāː/ |

ອາຟິກ/ອາຟຣິກ (*อาฟรีก) afik/afrik /aː fīk/-/aː frīk/ |

Afrique /a fʁik/ |

ອາຟິກາ/ອາຟຣິກາ afika/afrika |

'Africa' |

| หมากแอปเปิล mak aeppoen /mȁːk ʔɛ̏p pɤ̂n/ |

ผลแอปเปิล phon aeppoen /pʰǒn ʔɛ́p pɤ̂n/ |

ຫມາກປົ່ມ/ໝາກປົ່ມ (*หมากป่ม) mak pôm /mȁːk pōm/ |

pomme /pɔm/ |

'apple' | |

| เนย noei /nɤ̀ːj/ |

เนย noei /nɤ̄ːj/ |

ເບີ/ເບີຣ໌ (*เบอร์) bue /bə`ː/ |

beurre /bœʁ/ |

'butter' | |

| ไวน์ wai /wáːj/ |

ไวน์ wai /wāːj/ |

ແວງ (*แวง) vèng /ʋɛ́ːŋ/ |

vin /vɛ̃/ |

'wine' | |

| คนส่งไปรษณีย์ khon song praisani /kʰón sōŋ pàj sáʔ níː/ |

คนส่งไปรษณีย์ khon song praisani /kʰōn sòŋ prāj sàʔ nīː/ |

ຟັກເຕີ/ຟັກເຕີຣ໌ (*ฟักเตอร์) fakteu /fāk təː/ |

facteur /fak tœʁ/ |

ຄົນສົ່ງໜັງສື (*คนส่งหนังสื) khôn song nangsue |

'postman', 'mailman' (US) |

| ปลาวาฬ pla wan /paː wáːn/ |

ปลาวาฬ pla wan /plāː wāːn/ |

ປາບາແລນ (*ปลาบาแลน) pa balèn /paː baː lɛ́ːn/ |

baleine /ba lɛn/ |

'whale' | |

| เคมี khemi /kʰéː míː/ |

เคมี khemi /kʰēː mīː/ |

ຊີມີ (*ซิมี) ximi /síː míː/ |

chimie /ʃi mi/ |

ເຄມີ khémi |

'chemistry' |

| บิลเลียด binliat /bin lîat/ |

บิลเลียด binliat /bīn lîat/ |

ບີຢາ (*บียา) biya /bìː yàː/ |

billard /bi jaʁ/ |

ບິລລຽດ binliat |

'billiards' |

| ธนาณัติ thananat /tʰāʔ náː nāt/ |

ธนาณัติ thananat /tʰáʔ nāː nát/ |

ມັງດາ (*มังดา) mangda /máŋ daː/ |

mandat /mɑ̃ da/ |

ທະນານັດ thananat |

'money order' |

| กรัม kram /kàm/ |

กรัม kram /krām/ |

ກາມ/ກຣາມ (*กราม) kam/kram /kaːm/-/kraːm/ |

gramme /ɡʁam/ |

'gramme', 'gram' |

Vietnamese loanwords

Because of the depopulation of the left bank to Siam prior to French colonization, the French who were already active in Vietnam brought Vietnamese to boost the population of the cities and help administer the region. Many Lao that received a French-language education during the period of French Indochina were educated in French-language schools in Vietnam, exposing them to French and Vietnamese languages and cultures. As the Vietnamese communists supported the Pathét Lao forces, supplying Lao communist militia with weaponry and training during the two-decade-long Laotian Civil War, large numbers of Vietnamese troops have been stationed at various times in Laos' post-independence history, although the Vietnamese military presence began to wane in the late 1980s as Laos pursued closer relations with its other neighbors and entered the market economy. Since market reforms in Vietnam, market liberalization has been the main focus between the two countries now.

| Isan | Thai | Lao | Vietnamese | Lao alternate | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ก๋วยเตี๋ยว kuaitiao /kŭaj tǐaw/ |

ก๋วยเตี๋ยว kuaitiao /kǔaj tǐaw/ |

ເຝີ feu /fɤ̌ː/ |

phở /fə ̉ː/ |

ກ໋ວຽຕຽວ kouay tio |

'Vietnamese noodle soup' |

| เยื้อน yuean /ɲɯ̂an/ |

งดเว้น ngotwen /ŋót wén/ |

ກຽງ kiang /kiaŋ/ |

kiêng /kiə̯ŋ/ |

ເຍຶ້ອນ gnuan |

'to abstain', 'to refrain' |

| ฉาก chak /tɕʰȁːk/ |

ฉาก chak /tɕʰàːk/ |

ອີແກ້ i kè /ʔìː kɛ̂ː/ |

ê-ke[c] /e kɛ/ |

ສາກ sak |

'carpenter's square', 'T-square' |

| เฮ็ดงาน het ngan /hēt ŋáːn/ |

ทำงาน tham ngan /tʰām ŋāːn/ |

ເຮັດວຽກ het viak /hēt ʋîak/ |

việc /viə̯̣k/ |

ເຮັດງານ hét ngan |

'to work', 'to labour' |

Phonology

Consonants

Many consonants in Lao have a labialized and plain form, thus creating a phonemic contrast. The complete inventory of Lao consonants is as shown in the table below:[38][39]

Initial consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lab. | plain | lab. | plain | lab. | plain | lab. | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ŋʷ | |||||

| Plosive | voiced | b | d | |||||||

| voiceless | p | t | tɕ | tɕʷ | k | kʷ | ʔ | ʔʷ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tʷʰ | kʰ | kʷʰ | |||||

| Fricative | f | s | sʷ | h | ||||||

| Approximant | ʋ~w | l | lʷ | j | ||||||

Final consonants

All plosive sounds (besides the glottal stop /ʔ/) are unreleased in final position. Hence, final /p/, /t/, and /k/ sounds are pronounced as [p̚], [t̚], and [k̚] respectively.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | p | t | k | ʔ* | |

| Approximant | w | j |

- The glottal stop appears at the end when no final follows a short vowel.

Vowels

All vowels make a phonemic length distinction. Diphthongs are all centering diphthongs with falling sonority.[38] The monophthongs and diphthongs are as shown in the following table:[38][39]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tones

Lao has six lexical tones.[40] However, the Vientiane and the Luang Prabang dialects have five tones (see below) (Brown 1965; Osatananda, 1997, 2015).[41][42][43]

Smooth syllables

There are six phonemic tones in smooth syllables, that is, in syllables ending in a vowel or other sonorant sound ([m], [n], [ŋ], [w], and [j]).

| Name | Diacritic on ⟨e⟩ | Tone letter | Example | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rising | ě | ˨˦ or ˨˩˦ | /kʰǎː/ ຂາ |

leg |

| High level | é | ˦ | /kʰáː/ ຄາ |

stuck |

| High falling | ê | ˥˧ | /kʰâː/ ຄ້າ |

trade |

| Mid level | ē | ˧ | /kʰāː/ ຂ່າ, ຄ່າ |

galangal, value resp. |

| Low level | è | ˩ | /kàː/ ກາ |

crow |

| Low falling | e᷆ (also ȅ) |

˧˩ | /kʰa᷆ː/ ຂ້າ |

kill, servant |

| Vientiane (Osatananda, 1997, p. 40)[42] |

Luang Prabang (Osatananda, 2015, p. 122)[43] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Tone letters | Example(s) | Name | Tone letters | Example(s) |

| low | 1(3) or ˩(˧)[d] | /kʰaː˩(˧)/ ຂາ "leg" /kaː˩(˧)/ ກາ "crow" |

high-falling-to-mid-level | 533 or ˥˧˧ | /kʰaː˥˧˧/ ຂາ "leg" |

| high | 35 or ˧˥ | /kʰaː˧˥/ ຄາ "stuck" | low rising | 12 or ˩˨ | /kʰaː˩˨/ ຄາ "stuck" /kaː˩˨/ ກາ "crow" |

| mid level | 33 or ˧˧ | /kʰaː˧˧/ ຂ່າ "galangal" /kʰaː˧˧/ ຄ່າ "value" |

mid-falling[e] | 32 or ˧˨ | /kʰaː˧˨/ ຂ່າ "galangal" /kʰaː˧˨/ ຄ່າ "trade" |

| mid-fall | 31 or ˧˩ | /kʰaː˧˩/ ຂ້າ "kill" | high level-falling[f] | 552 or ˥˥˨ | /kʰaː˥˥˨/ ຂ້າ "kill" |

| high-fall | 52 or ˥˨ | /kʰaː˥˨/ ຄ້າ "trade" | mid-rising[g] | 34 or ˧˦ | /kʰaː˧˦/ ຄ້າ "trade" |

- ^ Northeastern Lao is sometimes considered a separate language, as it is traditionally spoken by Phuan tribal members, a closely related but distinct Tai group. Also spoken in a few small and scattered Tai Phuan villages in Sukhothai, Uttaradit, and Phrae.

- ^ Southern Lao gives way to Northern Khmer in Sisaket, Surin, and Buriram, and to Khorat Thai and, to some extent, Northern Khmer in Nakhon Ratchasima.

- ^ Itself a loan word from French équerre

- ^ The tone letters are 13 (˩˧) in citation form or before a pause and 11 (˩˩) elsewhere, e.g., /haː˩˧ paː˩˧/ ຫາປາ "look for fish" becomes [haː˩˩ paː˩˧] (Osatananda, 1997, p. 119).[42]

- ^ This tone is realized as a low level tone (22 or ˨˨) in a checked syllable with a short vowel (e.g., [kʰap˨˨] ຄັບ "tight") (Osatananda, 2015, p. 122).[43]

- ^ This tone is realized as a mid level-falling tone (332 or ˧˧˨) in a checked syllable with a long vowel (e.g., [kʰaːp˧˧˨] ຂາບ "prostrate") (Osatananda, 2015, p. 122).[43]

- ^ This tone is realized as a low rising tone (23 or ˨˧) in a checked syllable with a long vowel (e.g., [kʰaːp˨˧] ຄາບ "dead skin of a reptile") (Osatananda, 2015, p. 122).[43]

Checked syllables

The number of contrastive tones is reduced to four in checked syllables, that is, in syllables ending in an obstruent sound ([p], [t], [k], or the glottal stop [ʔ]).

| Tone | Example | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| high | /hák/ ຫັກ |

break |

| mid | /hāk/ ຮັກ |

love |

| low-falling | /ha᷆ːk/ ຫາກ |

if, inevitably |

| falling | /hâːk/ ຮາກ |

vomit, root |

Syllables

Lao syllables are of the form (C)V(C), i.e., they consist of a vowel in the syllable nucleus, optionally preceded by a single consonant in the syllable onset and optionally followed by a single consonant in the syllable coda. The only consonant clusters allowed are syllable initial clusters /kw/ or /kʰw/. Any consonant may appear in the onset, but the labialized consonants do not occur before rounded vowels.[38]

One difference between Thai and Lao is that in Lao initial clusters are simplified. For example, the official name of Laos is Romanized as Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao, with the Thai analog being Satharanarat Prachathipatai Prachachon Lao (สาธารณรัฐประชาธิปไตยประชาชนลาว), indicating the simplification of Thai pr to Lao p.

Only /p t k ʔ m n ŋ w j/ may appear in the coda. If the vowel in the nucleus is short, it must be followed by a consonant in the coda; /ʔ/ in the coda can be preceded only by a short vowel. Open syllables (i.e., those with no coda consonant) and syllables ending in one of the sonorants /m n ŋ w j/ take one of the six tones, syllables ending in /p t k/ take one of four tones, and syllables ending in /ʔ/ take one of only two tones.[38]

Morphology

The majority of Lao words are monosyllabic, and are not inflected to reflect declension or verbal tense, making Lao an analytic language. Special particle words serve the purpose of prepositions and verb tenses in lieu of conjugations and declensions. Lao is a subject–verb–object (SVO) language, although the subject is often dropped. In contrast to Thai, Lao uses pronouns more frequently.

Numbers

| Number | Gloss | Number | Gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ໐ ສູນ/ສູນຍ໌ soun |

/sǔːn/ | 0 'zero' nulla |

໒໑ ຊາວເອັດ xao ét |

/sáːu ʔét/ | 21 'twenty-one' XXI |

| ໑ ນຶ່ງ nung |

/nɨ̄ːŋ/ | 1 'one' I |

໒໒ ຊາວສອງ xao song |

/sáːu sɔ̆ːŋ/ | 22 'twenty-two' XXII |

| ໒ ສອງ song |

/sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 2 'two' II |

໒໓ ຊາວສາມ xao sam |

/sáːu săːm/ | 23 'twenty-three' XXII |

| ໓ ສາມ sam |

/sǎːm/ | 3 'three' III |

໓໐ ສາມສິບ sam sip |

/săːm síp/ | 30 thirty XXX |

| ໔ ສີ່ si |

/sīː/ | 4 four IV |

໓໑ ສາມສິບເອັດ sam sip ét |

/săːm síp ʔét/ | 31 'thirty-one' XXXI |

| ໕ ຫ້າ ha |

/hȁː/ | 5 'five' V |

໓໒ ສາມສິບສອງ sam sip song |

/săːm síp sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 32 'thirty-two' XXXII |

| ໖ ຫົກ hôk |

/hók/ | 6 six VI |

໔໐ ສີ່ສິບ si sip |

/sīː síp/ | 40 'forty' VL |

| ໗ ເຈັດ chét |

/t͡ɕét/ | 7 'seven' VII |

໕໐ ຫ້າສິບ ha sip |

/hȁː síp/ | 50 'fifty' L |

| ໘ ແປດ pèt |

/pɛ̏ːt/ | 8 'eight' VIII |

໖໐ ຫົກສິບ hôk sip |

/hók síp/ | 60 sixty LX |

| ໙ ເກົ້າ kao |

/kȃo/ | 9 nine IX |

໗໐ ເຈັດສິບ chét sip |

/t͡ɕét síp/ | 70 'seventy' LXX |

| ໑໐ ສິບ sip |

/síp/ | 10 ten X |

໘໐ ແປດສິບ pèt sip |

/pɛ̏ːt sìp/ | 80 'eighty' LXXX |

| ໑໑ ສິບເອັດ sip ét |

/síp ʔét/ | 11 'eleven' XI |

໙໐ ເກົ້າສິບ |

/kȃo síp/ | 90 'ninety' XC |

| ໑໒ ສິບສອງ |

/síp sɔ̌ːŋ/ | 12 'twelve' XII |

໑໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ຮ້ອຍ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) hɔ̂ːj/ | 100 'one hundred' C |

| ໑໓ ສິບສາມ |

/síp săːm/ | 13 'thirteen' XIII |

໑໐໑ (ນຶ່ງ)ຮ້ອຍເອັດ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) hɔ̂ːj ʔét/ | 101 'one hundred one' CI |

| ໑໔ ສິບສີ່ |

/síp sīː/ | 14 'fourteen' XIV |

໑໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ພັນ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán/ | 1,000 'one thousand' M |

| ໑໕ ສິບຫ້າ |

/síp hȁːː/ | 15 'fifteen' XV |

໑໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ໝື່ນ/(ນຶ່ງ)ຫມື່ນ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) mɨ̄ːn/ | 10,000 ten thousand X. |

| ໑໖ ສິບຫົກ |

/síp hók/ | 16 'sixteen' XVI |

໑໐໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ແສນ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) sɛ̆ːn/ | 100,000 'one hundred thousand' C. |

| ໑໗ ສິບເຈັດ |

/síp t͡ɕét/ | 17 seventeen XVII |

໑໐໐໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ລ້ານ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) lâːn/ | 1,000,000 'one million' |

| ໑໘ ສິບແປດ |

/síp pɛ́ːt/ | 18 'eighteen' XVIII |

໑໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ພັນລ້ານ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000 'one billion' |

| ໑໙ ສິບເກົ້າ |

/síp kȃo/ | 19 'nineteen' XIX |

໑໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ລ້ານລ້ານ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) lâːn lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000,000 'one trillion' |

| ໒໐ ຊາວ(ນຶ່ງ) xao(nung) |

/sáːu (nɨ̄ːŋ)/ | 20 'twenty' XX |

໑໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐໐ (ນຶ່ງ)ພັນລ້ານລ້ານ |

/(nɨ̄ːŋ) pʰán lâːn lâːn/ | 1,000,000,000,000,000 'one quadrillion' |

Writing system

Lao script

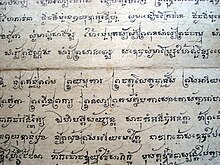

The Lao script, derived from the Khmer alphabet of the Khmer Empire in the 14th century,[44] is ultimately rooted in the Pallava script of Southern India, one of the Brahmi scripts.[45] Although the Lao script bears resemblance to Thai, the former contains fewer letters than Thai because by 1960 it was simplified to be fairly phonemic, whereas Thai maintains many etymological spellings that are pronounced the same.[46]

The script is traditionally classified as an abugida, but Lao consonant letters are conceived of as simply representing the consonant sound, rather than a syllable with an inherent vowel.[46] Vowels are written as diacritic marks and can be placed above, below, in front of, or behind consonants. The script also contains distinct symbols for numerals, although Arabic numerals are more commonly used.

Lao is written in the Tai Tham script for liturgical purposes[45] and is still used in temples in Laos and Isan.

Indication of tones

Experts disagree on the number and nature of tones in the various dialects of Lao. According to some, most dialects of Lao and Isan have six tones, those of Luang Prabang have five. Tones are determined as follows:

| Tones | Long vowel, or vowel plus voiced consonant | Long vowel plus unvoiced consonant | Short vowel, or short vowel plus unvoiced consonant | Mai ek (◌່) | Mai tho (◌້) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High consonants | rising | low falling | high | mid | low falling |

| Mid consonants | low rising | low falling | high | mid | high falling |

| Low consonants | high | high falling | mid | mid | high falling |

A silent ຫ (/h/) placed before certain consonants will place the proceeding consonant in the high class tone. This can occur before the letters ງ /ŋ/, ຍ /ɲ/, ຣ /r/, and ວ /w/ and combined in special ligatures (considered separate letters) such as ຫຼ /l/, ໜ /n/, and ໝ /m/. In addition to ອ່ (low tone) and ອ້ (falling tone), there also exists the rare ອ໊ (high) ອ໋ (rising) tone marks.

Tai Tham script

Traditionally, only secular literature was written with the Lao alphabet. Religious literature was often written in Tai Tham, a Mon-based script that is still used for the Tai Khün, Tai Lü, and formerly for Kham Mueang.[47] The Lao style of this script is known as Lao Tham.[48]

Khom script

Mystical, magical, and some religious literature was written in Khom script (Aksar Khom), a modified version of the Khmer script.[49]

See also

References

- ^ PDR Lao at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

Isan (Thailand Lao) at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Lao language at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "Lao". About World Languages. Archived from the original on 2017-12-27. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ "Ausbau and Abstand languages". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. 1995-01-20. Archived from the original on 2013-01-19. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ Hays, Jeffrey. "LAO LANGUAGE: DIALECTS, GRAMMAR, NAMES, WRITING, PROVERBS AND INSULTS | Facts and Details". factsanddetails.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-02. Retrieved 2020-12-19.

- ^ a b c d Paul, L. M., Simons, G. F. and Fennig, C. D. (eds.). 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Seventeenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com Archived 2007-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edmondson, Jerold A.; Gregerson, Kenneth J. (2007). "The Languages of Vietnam: Mosaics and Expansions". Language and Linguistics Compass. 1 (6): 727–749. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00033.x.

- ^ Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (1 January 2014). "Layers of Chinese Loanwords in Protosouthwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai". Manusya: Journal of Humanities. 17 (3): 47–68. doi:10.1163/26659077-01703004.

- ^ a b Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2009). "Proto-Southwestern-Tai revised: A new reconstruction" (PDF). Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 2: 119–143. hdl:1885/113003.

- ^ Greenhill, Simon J.; Blust, Robert; Gray, Russell D. (3 November 2008). "The Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database: From Bioinformatics to Lexomics". Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online. 4: 271–283. doi:10.4137/ebo.s893. PMC 2614200. PMID 19204825. ProQuest 1038141425.

- ^ Jonsson, Nanna L. (1991) Proto Southwestern Tai. Ph.D dissertation, available from UMI.

- ^ a b Huffman, Franklin E. (1973). "Thai and Cambodian – A Case of Syntactic Borrowing?". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 93 (4): 488–509. doi:10.2307/600168. JSTOR 600168.

- ^ Khanittanan, W. (2001). "Khmero-Thai: The great change in the history of Thai". ภาษาและภาษาศาสตร์. 19 (2): 35–50.

- ^ Gunn, G. C. (2004). 'Laotinization' in Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Ooi, K. G. (ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- ^ a b Diller, A. V. N., Edmondson, J. A. & Luo, Y. (2004) Tai-Kadai languages. (pp. 49–56). New York, NYC: Routledge.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, M. (1998). The Lao Kingdom of Lan Xang: Rise and Decline. (pp. 40–60). Banglamung, Thailand: White Lotus Press.

- ^ a b c Phra Ariyuwat. (1996). Phya Khankhaak, the Toad King: A Translation of an Isan Fertility Myth in Verse. Wajuppa Tossa (translator). (pp. 27–34). Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press.

- ^ Holt, J. C. (2009). Spirits of the Place: Buddhism and Lao Religious Culture. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 14.

- ^ Holt, J. C. (2009). p. 38.

- ^ Burusphat, S., Deepadung, S., & Suraratdecha, S. et al. (2011). "Language vitality and the ethnic tourism development of the Lao ethnic groups in the western region of Thailand" Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Lao Studies, 2(2), 23–46.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, M. (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. (pp. 1–20).

- ^ Keyes, Charles (2013), Finding Their Voice: Northeastern Villagers and the Thai State, Silkworm Books.

- ^ Platt, M. B. (2013). Isan Writers, Thai Literature Writing and Regionalism in Modern Thailand. (pp. 145–149). Singapore: NUS Press.

- ^ Ivarson, S. (2008). Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space Between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945. (pp. 127–135, 190–197) Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

- ^ Compton, C. J. (2009) Contemporary Lao Studies: Research on Development, Language and Culture, and Traditional Medicine. Compton, C. J., Hartmann, J. F. Sysamouth, V. (eds.). (pp. 160–188). San Francisco, CA: Center for Lao Cultural Studies.

- ^ Hartmann, J. (2002). Vientiane Tones. Archived 2020-08-11 at the Wayback Machine Center for Southeast Asian Studies. DeKalb: University of Northern Illinois. Based on Crisfield-Hartmann 2002/Enfield 2000, Brown 1965, and Chittavoravong (1980) (unpublished).

- ^ เรืองเดช ปันเขื่อนขัติย์. ภาษาถิ่นตระกูลไทย. กทม. สถาบันวิจัยภาษาและวัฒนธรรมเพื่อการพัฒนาชนบทมหาวิทยาลัยมหิดล. 2531.

- ^ a b Enfield, N. J. (1966). A Grammar of Lao. Mouton de Gruyter: New York, NY. 2007 reprint. p. 19.

- ^ Osantanda, V. (2015). "Lao Khrang and Luang Phrabang Lao: A Comparison of Tonal Systems and Foreign-Accent Rating by Luang Phrabang Judges." The Journal of Lao Studies. pp. 110–143. Special Issue 2(2015).

- ^ Hartmann, J. (2002). Louang Phrabang Tones. Archived 2022-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Based Brown (1965).

- ^ Hartmann, J. (2002). 'Spoken Lao—A regional approach.' SEASITE Laos. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

- ^ Hmong Research Group (2009). Central Lao Tones (Savannakhét). Archived 2010-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- ^ Davis, G. W. (2015). The Story of Lao r: Filling in the Gaps Archived 2021-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. The Journal of Lao Studies, Special 2(2015), pps 97–109.

- ^ Hartmann, J. (2002). Southern Lao Tones (Pakxé). Archived 2020-07-13 at the Wayback Machine Based on Yuphaphann Hoonchamlong (1981).

- ^ Hartmann, J. (1971). "A model for the alignment of dialects in southwestern Tai" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 65 (2): 72–87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-04-18.

- ^ a b L'Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF). Laos. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.francophonie.org/Laos.html Archived 2017-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Panthamaly, P. (2008). Lao PDR. In B. Indrachit & S. Logan (eds.), Asian communication handbook 2008 (pp. 280–292). Singapore: Asian Media Information and Communication Centre.

- ^ a b c d e Blaine Erickson, 2001. "On the Origins of Labialized Consonants in Lao" Archived 2017-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Analysis based on L. N. Morev, A. A. Moskalyov and Y. Y. Plam, (1979). The Lao Language. Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences, Institute of Oriental Studies. Accessed 2009-12-19.

- ^ a b Enfield, N. J. (2007). A Grammar of Lao. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ^ Blaine Erickson, 2001. "On the Origins of Labialized Consonants in Lao" Archived 2017-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Analysis based on T. Hoshino and R. Marcus (1981). Lao for Beginners: An Introduction to the Spoken and Written Language of Laos. Rutland/Tokyo: Tuttle. Accessed 2009-12-19.

- ^ Brown, J. Marvin. 1965. From Ancient Thai to Modern Dialects. Bangkok: Social Science Association Press.

- ^ a b c Osatananda, Varisa (1997). Tone in Vientiane Lao (Thesis). ProQuest 304347191.

- ^ a b c d e Osatananda, Varisa (August 2015). "Lao Khrang and Luang Phrabang Lao: A comparison of tonal systems and foreign-accent rating by Luang Phrabang judges" (PDF). The Journal of Lao Studies. Special Issue 2: 110–143.

- ^ Benedict, Paul K. (August 1947). "Languages and Literatures of Indochina". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 6 (4): 379–389. doi:10.2307/2049433. JSTOR 2049433. S2CID 162902327. ProQuest 1290485784.

- ^ a b UCLA International Institute, (n.d.). "Lao" Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2010-07-27.

- ^ a b Unicode. (2019). Lao. In The Unicode Standard Version 12.0 (pp. 635–637). Mountain View, CA: Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Everson, Michael, Hosken, Martin, & Constable, Peter. (2007). Revised proposal for encoding the Lanna script in the BMP of the UCS Archived 2019-06-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kourilsky, Grégory & Berment, Vincent. (2005). Towards a Computerization of the Lao Tham System of Writing Archived 2007-08-02 at the Wayback Machine. In First International Conference on Lao Studies.

- ^ Igunma, Jana. (2013). Aksoon Khoom: Khmer Heritage in Thai and Lao Manuscript Cultures. Tai Culture, 23: Route of the Roots: Tai-Asiatic Cultural Interaction.

Further reading

- Lew, Sigrid. 2013. "A linguistic analysis of the Lao writing system and its suitability for minority language orthographies".

- ANSI Z39.35-1979, System for the Romanization of Lao, Khmer, and Pali, ISBN 0-88738-968-6.

- Hoshino, Tatsuo and Marcus, Russel. (1989). Lao for Beginners: An Introduction to the Spoken and Written Language of Laos. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-1629-8.

- Enfield, N. J. (2007). A Grammar of Lao. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-018588-1.

- Cummings, Joe. (2002). Lao Phrasebook: A Language Survival Kit. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-168-2.

- Mollerup, Asger. Thai–Isan–Lao Phrasebook. White Lotus, Bangkok, 2001. ISBN 974-7534-88-6.

- Kerr, Allen. (1994). Lao–English Dictionary. White Lotus. ISBN 974-8495-69-8.

- Simmala, Buasawan and Benjawan Poomsan Becker (2003), Lao for Beginners. Paiboon Publishing. ISBN 1-887521-28-3