Contents

Thomas Sims was an African American who escaped from slavery in Georgia and fled to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1851. He was arrested the same year under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, had a court hearing, and was forced to return to enslavement. A second escape brought him back to Boston in 1863, where he was later appointed to a position in the U.S. Department of Justice in 1877.[1] Sims was one of the first slaves to be forcibly returned from Boston under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The failure to stop his case from progressing was a significant blow to the abolitionists, as it showed the extent of the power and influence which slavery had on American society and politics. The case was one of many events leading to the American Civil War.

Early life and family

Sims was born in Savannah, Georgia to James Sims, a white Slave overseer on the Potter Rice Plantation, and Minda Campbell, a slave under rice planter James Potter.[2] The exact date of his birth is unknown, but it is estimated to be around 1828.[2] He was the brother of Isabella, Cornilla and James M. Simms, another notable African American of the time.[3] Before his escape, Thomas Sims worked as a bricklayer for Potter.[1] During this time he also married and had children with a free African American woman.[1]

Escape from slavery

Sims made his escape on February 21, 1851, by stowing away on the M. & J.C. Gilmore.[1] He was 23 at the time.[1] On March 6, right before the ship's arrival to Boston, the ship's crew discovered Sims.[1] Sims tried to convince them that he was a freed slave from Florida, but the crew did not believe him and locked him up in a cabin.[1] Sims escaped before authorities came,[1] and from then until his arrest in April, he stayed at 153 Ann Street, a boarding house for African American sailors.[1] According to newspaper reports of the time, he "made no effort to conceal himself" while living there,[4] but was not caught until he sent his address to his wife asking for money.[1]

Arrest and trial

Once James Potter, Sim's owner, realized Sims whereabouts, he sent his agent, John B. Bacon, to capture Sims. Bacon coordinated together with Seth J. Thomas and the authorities of Boston, including U.S. Commissioner George T. Curtis. On April 3, 1851, Sims was arrested. There was a struggle and one of the policemen assigned to the case, Asa O. Butman, was stabbed by Sims in the thigh.[1]

The trial took place three days after his arrest and garnered much attention from the abolitionists and people of the North. Extra precautions were taken at the Court House. Between 100 and 200 policemen were stationed and chains were placed around the courthouse to prevent the crowds from swarming the building.[1]

Unintentionally, however, the chains became a symbol of the influence of slavery in the North. Individuals who needed to enter the Court House had to crouch under the chains, and as Henry Longfellow put it, "Shame that the great Republic, 'the refuge of the oppressed,' should stoop so low as to become the Hunter of Slaves." Chief Justice Wells was one of the few who refused to bend down to cross as he believed it lowered both his dignity and that of the city of Boston.[1]

The "trial" (Commissioner Curtis was not a judge) that followed was a matter of whether personal property or individual liberty prevailed in the end. Each side tried to explain why one was predominantly superior over the other, with differing viewpoints presented throughout the case. The prosecution produced the papers that showed that Sims was a former slave and called witnesses to attest to this fact.[5] The defense (Robert Rantoul Jr., Charles Greely Loring, and Samuel Edmund Sewall)[6] had a harder time as the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act favored the prosecution of the case. The Fugitive Slave Act stated that the testimonies of escaped slaves on trial could not be used as actual evidence in the hearing, but because the act also required a trial in a "summary manner," there was not adequate time for the defense to find their witnesses.[1]

In Rantoul's opening statement for Sims, he tried explaining that the Constitution did not allow for people bound by service to be sent back without full proof, which was not being given at the moment.[5] Sims' lawyers attempted to buy him more time, claiming that Sims was still a free man by being in Boston and questioning the Commissioner's authority to remand Sims, when he was not even a judge.[5] Commissioner Curtis gave them the weekend to continue preparing for the case, as he wanted be fair and allow them to present a more thoroughly fleshed out case for Sims.[7] Later, Rantoul argued the Fifth Amendment to the court, claiming that Sims was being deprived of his rights to life, liberty, and property. He also attacked the constitutionality of the law itself, trying to find something to be able to let Sims go free.[5]

The Boston Vigilance Committee looked to find some way to help free Sims while outside of the courtroom, and tried to think of everything that they could in order to help at least give Sims more time. They attempted to submit a writ of replevin and to ask for habeas corpus, but neither succeeded, one because of problems with feasibility and the other because Chief Justice Shaw dismissed their calls for it.[7]

At the conclusion of the case, the court ruled that Sims would be sent back to the South. Commissioner Curtis stated that he would have liked to pass on the duty to an actual tribunal, but there were none available and thus, he had to do it. Sims was officially labeled a slave of James Potter and if the Georgia courts wanted to reexamine the case after Sims was returned, they were allowed to.[7]

Return to slavery

Following the court trial, Sims was sent back to Georgia against the strong protests of abolitionists.[8] The Boston Vigilance Committee, which had previously helped Shadrach Minkins, another fugitive slave, escape the custody of U.S. Marshals,[7] became desperate and came up with multiple plans to free Sims, including placing mattresses under Sims' cell window so that he could jump out and make his getaway in a horse and chaise.[7] The sheriff, however, barred the window before they could act.[7]

On April 13, Sims was marched down to a ship and returned to Georgia under military protection. Sims exclaimed that he would rather be killed and asked for a knife multiple times.[8] Many people marched in solidarity with Sims to the wharf.[7] Upon his return to Savannah, Sims was publicly whipped 39 times[1] and sold in a slave auction to a new owner in Mississippi.[8] In Mississippi he was put to work as a bricklayer in Vicksburg.[9]

Later years

Afterwards, Charles Devens, the U.S. Marshal who was ordered to return Sims to Georgia, unsuccessfully tried to buy Sims' freedom.[8] Sims was able to escape yet again, and returned to Boston in 1863 during the Civil War.[8] According to a May 1863 account in the Kenosha Telegraph Courier, "When the siege [of Vicksburg] began, he determined to escape. Selecting a few trusty companions, he took a boat, with his wife and child, and rowed down the river. The night was moonlight, and there was great risk of discovery, but the hand of Providence drew a cloud over the moon as the voyagers passed the rebel batteries. The party met no accident, and are safe in Boston. In regard to matters at Vicksburg, Sims states that the rebel army is upon short rations, and is in a terrible condition."[9]

Devens, however, did not forget about Sims, and when he became U.S. Attorney General in 1877,[10] Devens appointed Sims to a position in the U.S. Department of Justice.[1]

Reactions

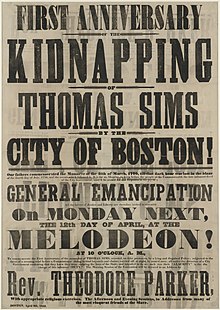

The "Sims Tragedy" was a major controversy among the abolitionists in Massachusetts and drew sympathy from many other abolitionists, as well. The following year, in 1852, his arrest and trial were remembered in a church ceremony featuring Reverend Theodore Parker.[11]

Three years after Sims' arrest, Judge Edward G. Loring ordered another fugitive slave, Anthony Burns, back to slavery in Virginia.[11] Sims' and Burns' cases are often compared, and, similar to Sims, Burns was escorted by the U.S. Marines to a ship headed for Virginia.[7] By the time of Burns' deportation, his cause had become so famous that 50,000 people watched federal officers take him to the wharf.[11] Within two years, Burns was back in Boston after the abolitionists raised $1,300 to pay for Burns' freedom.[7]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Levy, Leonard W. (January 1950). "Sims' Case: The Fugitive Slave Law in Boston in 1851". The Journal of Negro History. 35 (1): 39–74. doi:10.2307/2715559. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2715559. S2CID 150180859.

- ^ a b David, Robert S. (February 5, 2017). "Thomas Sim's epic struggle for freedom". Chattanooga Times Free Press.

- ^ Martin, Susan (February 2018). "'They belonging to themselves': Minda Campbell Redeems Her Family from Slavery". Massachusetts Historical Society.

- ^ "Arrest of Another Fugitive Slave". Boston Daily Evening Transcript. April 4, 1851.

- ^ a b c d "Redirecting". heinonline.org. Retrieved 2018-11-27.(registration required)[attribution needed]

- ^ "The Fugitive Slave Case". New-York Tribune. April 5, 1851. p. 6. Retrieved November 5, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schwartz, Harold (1954). "Fugitive Slave Days in Boston". The New England Quarterly. 27 (2): 191–212. doi:10.2307/362803. JSTOR 362803.

- ^ a b c d e "The Thomas Sims Case: Escaped to Freedom Only to Be Sent Back into Bondage". Black Then. 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ a b "A Child of the Fugitive Slave Law". The Telegraph-Courier. 1863-05-14. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ^ "The Trials of Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns". ComputerImages Corporation. 2012-03-04.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Stanley W. (2011). The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850–1860. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 117–121.

External links

- "Trial of Thomas Sims on an issue of personal liberty, April 7-11, 1851". Library of Congress: American Memory.