Contents

Camp Greene was the site of a training camp for the 1st United States Colored Infantry Regiment and other Colored Troops on Mason's Island, now known as Theodore Roosevelt Island, in Washington, D.C. The island was also a refugee camp for freedom seekers. It is situated in the Potomac River.[1] It has been made an Underground Railroad site on the National Park Service's Network to Freedom.

American Civil War

Refugee camp

Fleeing slavery, many escaped bondsmen and newly freed people made their way north, behind Union Army lines into northern cities. The people who fled slavery became known as "contrabands" and their numbers were so large that the United States government established contraband camps in 1861. The refugees were in need of shelter, medical care, clothing, food, and employment. In the metropolitan District of Columbia area, a camp called Freeman's Village was established on the Arlington Estate, but was soon overcrowded and disease-ridden. Mason's island then became a refugee camp.[1]

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation was signed into law on New Year's Day, 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln. It freed enslave people and it allowed for recruitment of African Americans in the Union Army.[1]

Union training camp

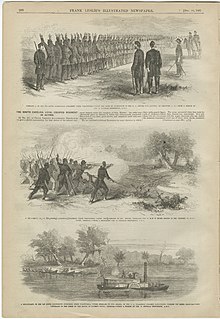

Army Chaplains W.G. Raymond and J.D. Turner, both of whom were white, recruited volunteers from temporary refugee camps, prisons, and hospitals. Most of the recruits came from the District of Columbia, including free men and freedom seekers, who had escaped slavery during the war.[1][3] Two of the recruits were Henry Bailey and John Chen, who escaped slavery in Suffolk and Caroline County, Virginia. The camp established in May 1863 was called Camp Greene.[1]

The recruits marched through Washington, D.C., on May 15 and they were trained and located on Mason's Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island) on May 19. They were stationed on an island due to the degree of animus against African Americans generally, which was heightened due to a major influx of African Americans into the city. It was common to see racially motivated violence.[3] There were people in the District of Columbia who did not want to see African Americans bear arms. There was fear in the military leadership of the reaction if they were to march within the city.[4] For their protection, the men were secretly moved to the island, known at that time as Mason's Island.[3] President Lincoln did not know where they were and the white recruiting officers were prevented from coming onto the island. A detachment of Massachusetts troops were brought in to protect the recruits after they were attacked in June by a gang who found out where they were located.[3]

The Bureau of Colored Troops was established on May 22, 1863. Blacks would serve as regular soldiers, not volunteers, and by June 30, ten more companies were formed with 700 men and stationed on the island. The 1st District of Columbia Colored Troops, the first black regiment formally mustered into service, was officially re-designated the 1st United States Colored Troops.[3][1] There was the state-based 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment and informal groups of soldiers in South Carolina and Kansas, but the 1st United States Colored Troops was the first federal regiment.[4] The black troops received 77% of the amount paid to white soldiers, they were subject to much harsher punishment, and many had to drill with broomsticks. If a black soldier was caught, they were killed (versus taken to a prisoner of war camp). Even though there was disparity in the way people were treated based upon their race, a lot of black men enlisted in the Army. There were 178,000 black troops that fought in the war from 1863 until the end of the war in 1865. About 40%, or 68,000 men, were killed in the war from injury or disease.[4]

Camp Greene recruits, which grew to about 1,000 soldiers at any one time, attended the Israel Bethel Church within Washington, D.C.[4] Walt Whitman was one of the people that came to the island to visit the troops.[1]

Camp Greene was a training and residential center for the 1st regiment until September 1863. They then served in Virginia, North Carolina, and as part of Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's Campaign of the Carolinas (March – April 1865).[3]

Network to Freedom

The Camp Greene and Contraband Camp is a National Park Service Network to Freedom designated site.[5]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aboard the Underground Railroad - Rush R. Sloane House". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ "Contraband Quarters, Mason's Island". Theodore Roosevelt Island National Memorial, The Theodore Roosevelt Center. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b c d e f "African Americans and the Defenses of Washington - Civil War Defenses of Washington". National Park Service. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Sandra (September 10, 1995). "Civil War Buffs Recall Glory of Black Soldiers". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- ^ "New NCR Sites Accepted into Network to Freedom at Santa Fe Public Review" (PDF). The Conductor. National Park Service - The National Underground Railroad Network To Freedom Program. Spring 2007. Retrieved 2021-06-02.