Contents

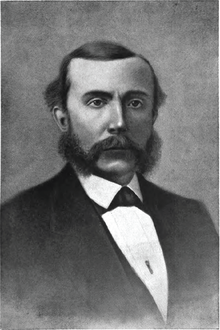

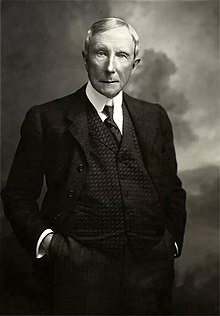

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He was one of the wealthiest Americans of all time[1][2][3][4] and one of the richest people in modern history.[5][6][3] Rockefeller was born into a large family in Upstate New York who moved several times before eventually settling in Cleveland, Ohio. He became an assistant bookkeeper at age 16 and went into several business partnerships beginning at age 20, concentrating his business on oil refining. Rockefeller founded the Standard Oil Company in 1870. He ran it until 1897 and remained its largest shareholder. In his retirement, he focused his energy and wealth on philanthropy, especially regarding education, medicine, higher education, and modernizing the American South.

Rockefeller's wealth soared as kerosene and gasoline grew in importance, and he became the richest person in the country, controlling 90% of all oil in the United States at his peak in 1900.[a] Oil was used in lamps, and as a fuel for ships and automobiles. Standard Oil was the greatest business trust in the United States. Through use of the company's monopoly power, Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and, through corporate and technological innovations, was instrumental in both widely disseminating and drastically reducing the production cost of oil.

Rockefeller's company and business practices came under criticism, particularly in the writings of author Ida Tarbell. The Supreme Court ruled in 1911 that Standard Oil must be dismantled for violation of federal antitrust laws. It was broken up into 34 separate entities, which included companies that became ExxonMobil, Chevron Corporation, and others—some of which remain among the largest companies by revenue worldwide. Consequently, Rockefeller became the country's first billionaire, with a fortune worth nearly 2% of the national economy.[7] His personal wealth was estimated in 1913 at $900 million, which was almost 3% of the US gross domestic product (GDP) of $39.1 billion that year.[8][full citation needed]

Rockefeller spent much of the last 40 years of his life in retirement at Kykuit, his estate in Westchester County, New York, defining the structure of modern philanthropy, along with other key industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie.[9] His fortune was used chiefly to create the modern systematic approach of targeted philanthropy through the creation of foundations that supported medicine, education, and scientific research.[10] His foundations pioneered developments in medical research and were instrumental in the near-eradication of hookworm in the American South,[11] and yellow fever[12] in the United States. He and Carnegie gave form and impetus through their charities to the work of Abraham Flexner, who in his essay "Medical Education in America" emphatically endowed empiricism as the basis for the US medical system of the 20th century.[13]

Rockefeller was the founder of the University of Chicago and Rockefeller University, and funded the establishment of Central Philippine University in the Philippines.[14][15][16] He was a devout Northern Baptist and supported many church-based institutions. He adhered to total abstinence from alcohol and tobacco throughout his life.[17] For advice, he relied closely on his wife, Laura Spelman Rockefeller: they had four daughters and a son together. He was a faithful congregant of the Erie Street Baptist Mission Church, taught Sunday school, and served as a trustee, clerk, and occasional janitor.[18] Religion was a guiding force throughout his life, and he believed it to be the source of his success. Rockefeller was also considered a supporter of capitalism based on a perspective of social Darwinism, and he was quoted often as saying, "The growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest."[19][20]

Early life

Rockefeller was the second of six children born in Richford, New York, to con artist William A. Rockefeller Sr. and Eliza Davison.[21] Rockefeller had an elder sister named Lucy and four younger siblings: William Jr., Mary, and fraternal twins Franklin (Frank) and Frances. His father was of English and German descent, while his mother was of Ulster Scot descent.[22] One source says that some ancestors were Huguenots, the Roquefeuille family, who fled to Germany from France during the reign of Louis XIV and a period of religious persecution. By the time their descendants immigrated to North America, their name had taken German form.[23] William Sr. worked first as a lumberman and then a traveling salesman. He claimed to be a "botanic physician" who sold elixirs, and was described by locals as "Big Bill" and "Devil Bill."[24] Unshackled by conventional morality, he led a vagabond existence and returned to his family infrequently.[21] Throughout his life, Bill was notorious for conducting schemes.[25] In between the births of Lucy and John, Bill and his mistress and housekeeper Nancy Brown had a daughter named Clorinda, who died young. Between John and William Jr.'s births, Bill and Nancy had another daughter, named Cornelia.[26]

Eliza was a homemaker and a devout Baptist who struggled to maintain a semblance of stability at home, as Bill was frequently gone for extended periods. She also put up with his philandering and his double life, which included bigamy. He permanently abandoned his family around 1855 and lived with second wife, Margaret L. Allen.[27]

Eliza was thrifty by nature and by necessity, and she taught her son that "willful waste makes woeful want".[28] John did his share of the regular household chores and earned extra money raising turkeys, selling potatoes and candy, and eventually lending small sums of money to neighbors.[29][30] He followed his father's advice to "trade dishes for platters" and always get the better part of any deal. Bill once bragged, "I cheat my boys every chance I get. I want to make 'em sharp." However, his mother was more influential in John's upbringing and beyond, while he distanced himself further and further from his father as his life progressed.[31] He later stated, "From the beginning, I was trained to work, to save, and to give."[32]

When he was a boy, his family moved to Moravia, New York, and to Owego, New York, in 1851, where he attended Owego Academy. In 1853, his family moved to Strongsville, Ohio, and he attended Cleveland's Central High School, the first high school in Cleveland and the first free public high school west of the Alleghenies. Then he took a ten-week business course at Folsom's Commercial College, where he studied bookkeeping.[33] Rockefeller was a well-behaved, serious, and studious boy despite his father's absences and frequent family moves. His contemporaries described him as reserved, earnest, religious, methodical, and discreet. He was an excellent debater and expressed himself precisely. He also had a deep love of music and dreamed of it as a possible career.[34]

Pre-Standard Oil career

As a bookkeeper

In September 1855, when Rockefeller was sixteen, he got his first job as an assistant bookkeeper working for a small produce commission firm in Cleveland called Hewitt & Tuttle.[35] He worked long hours and delighted, as he later recalled, in "all the methods and systems of the office."[36] He was particularly adept at calculating transportation costs, which served him well later in his career. Much of Rockefeller's duties involved negotiating with barge canal owners, ship captains, and freight agents. In these negotiations, he learned that posted transportation rates that were believed to be fixed could be altered depending on conditions and timing of freight and through the use of rebates to preferred shippers. Rockefeller was also given the duties of collecting debts when Hewitt instructed him to do so. Instead of using his father's method of presence to collect debts, Rockefeller relied on a persistent pestering approach.[37] Rockefeller received $16 a month for his three-month apprenticeship. During his first year, he received $31 a month, which was increased to $50 a month. His final year provided him $58 a month.[38]

As a youth, Rockefeller reportedly said that his two great ambitions were to make $100,000 (equivalent to $3.27 million[39] in 2023 dollars) and to live 100 years.[40]

Business partnership and Civil War service

In 1859, Rockefeller went into the produce commission business with two partners, Maurice B. Clark and George W. Gardner, under Clark, Gardner & Company, and they raised $4,000 ($135,644 in 2023 dollars) in capital.[41][42] Clark initiated the idea of the partnership and offered $2,000 towards the goal. Rockefeller had only $800 saved up at the time and so borrowed $1,000 from his father, "Big Bill" Rockefeller, at 10 percent interest.[43] Rockefeller went steadily ahead in business from there, making money each year of his career.[44] In their first and second years of business, Clark, Gardner & Rockefeller netted $4,400 (on nearly half a million dollars in business) and $17,000 worth of profit, respectively, and their profits soared with the outbreak of the American Civil War when the Union Army called for massive amounts of food and supplies. During the second year of the American Civil War, Gardner withdrew from the business, and the firm became Clark & Rockefeller.[41][42]

When the Civil War was nearing a close and with the prospect of those war-time profits ending, Clark & Rockefeller looked toward the refining of crude oil.[45] While his brother Frank fought in the Civil War, Rockefeller tended his business and hired substitute soldiers. He gave money to the Union cause, as did many rich Northerners who avoided combat. "I wanted to go in the army and do my part," Rockefeller said. "But it was simply out of the question. There was no one to take my place. We were in a new business, and if I had not stayed it must have stopped—and with so many dependent on it."

Rockefeller was an abolitionist who voted for President Abraham Lincoln and supported the then-new Republican Party.[46] As he said, "God gave me money", and he did not apologize for it. He felt at ease and righteous following Methodist preacher John Wesley's dictum, "gain all you can, save all you can, and give all you can."[47] During the Civil War, military consumption of oil drove the price up from $.35 a barrel in 1862 to as high as $13.75.[48] This created an oil-drilling glut, with thousands of speculators attempting to make their fortunes. Most failed, but those who struck oil did not even need to be efficient. They would blow holes in the ground and gather up the oil as they could, often leading to creeks and rivers flowing with wasted oil in the place of water.[49]

A market existed for the refined oil in the form of kerosene. Coal had previously been used to extract kerosene, but its tedious extraction process and high price prevented broad use. Even with the high costs of freight transportation and a government levy during the Civil War (the government levied a tax of twenty cents a gallon on refined oil), profits on the refined product were large. The price of the refined oil in 1863 was around $13 a barrel, with a profit margin of around $5 to $8 a barrel. The capital expenditures for a refinery at that time were small – around $1,000 to $1,500 and requiring only a few men to operate.[50] In this environment of a wasteful boom, the partners switched from foodstuffs to oil, building an oil refinery in 1863 in "The Flats", then Cleveland's burgeoning industrial area. The refinery was directly owned by Andrews, Clark & Company, which was composed of Clark & Rockefeller, chemist Samuel Andrews, and M. B. Clark's two brothers. The commercial oil business was then in its infancy. Whale oil had become too expensive for the masses, and a cheaper, general-purpose lighting fuel was needed.[51]

While other refineries would keep the 60% of oil product that became kerosene, but dump the other 40% in rivers and massive sludge piles,[52] Rockefeller used the gasoline to fuel the refinery, and sold the rest as lubricating oil, petroleum jelly and paraffin wax, and other by-products. Tar was used for paving, naphtha shipped to gas plants.[53] Likewise, Rockefeller's refineries hired their own plumbers, cutting the cost of pipe-laying in half. Barrels that cost $2.50 each ended up only $0.96 when Rockefeller bought the wood and had them built for himself.[citation needed] In February 1865, in what was later described by oil industry historian Daniel Yergin as a "critical" action, Rockefeller bought out the Clark brothers for $72,500 (equivalent to $1 million[39] in 2023 dollars) at auction and established the firm of Rockefeller & Andrews. Rockefeller said, "It was the day that determined my career."[54] He was well-positioned to take advantage of postwar prosperity and the great expansion westward fostered by the growth of railroads and an oil-fueled economy. He borrowed heavily, reinvested profits, adapted rapidly to changing markets, and fielded observers to track the quickly expanding industry.[55]

Beginning in the oil business

In 1866, William Rockefeller Jr., John's brother, built another refinery in Cleveland and brought John into the partnership. In 1867, Henry Morrison Flagler became a partner, and the firm of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was established. By 1868, with Rockefeller continuing practices of borrowing and reinvesting profits, controlling costs, and using refineries' waste, the company owned two Cleveland refineries and a marketing subsidiary in New York; it was the largest oil refinery in the world.[56][57] Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler was the predecessor of the Standard Oil Company.[citation needed]

Standard Oil

Founding and early growth

By the end of the American Civil War, Cleveland was one of the five main refining centers in the U.S. (besides Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, New York, and the region in northwestern Pennsylvania where most of the oil originated). By 1869 there was triple the kerosene refining capacity than needed to supply the market, and the capacity remained in excess for many years.[58]

On January 10, 1870, Rockefeller abolished the partnership of Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler,[59] forming Standard Oil of Ohio. Continuing to apply his work ethic and efficiency, Rockefeller quickly expanded the company to be the most profitable refiner in Ohio. Likewise, it became one of the largest shippers of oil and kerosene in the country. The railroads competed fiercely for traffic and, in an attempt to create a cartel to control freight rates, formed the South Improvement Company offering special deals to bulk customers like Standard Oil, outside the main oil centers. The cartel offered preferential treatment as a high-volume shipper, which included not just steep discounts/rebates of up to 50% for their product but rebates for the shipment of competing products.[60]

Part of this scheme was the announcement of sharply increased freight charges. This touched off a firestorm of protest from independent oil well owners, including boycotts and vandalism, which led to the discovery of Standard Oil's part in the deal. A major New York refiner, Charles Pratt and Company, headed by Charles Pratt and Henry H. Rogers, led the opposition to this plan, and railroads soon backed off. Pennsylvania revoked the cartel's charter, and non-preferential rates were restored for the time being.[62] While competitors may have been unhappy, Rockefeller's efforts did bring American consumers cheaper kerosene and other oil by-products. Before 1870, oil light was only for the wealthy, provided by expensive whale oil. During the next decade, kerosene became commonly available to the working and middle classes.[52]

Undeterred, though vilified for the first time by the press, Rockefeller continued with his self-reinforcing cycle of buying the least efficient competing refiners, improving the efficiency of his operations, pressing for discounts on oil shipments, undercutting his competition, making secret deals, raising investment pools, and buying rivals out. In less than four months in 1872, in what was later known as "The Cleveland Conquest" or "The Cleveland Massacre", Standard Oil absorbed 22 of its 26 Cleveland competitors.[63] Eventually, even his former antagonists, Pratt and Rogers, saw the futility of continuing to compete against Standard Oil; in 1874, they made a secret agreement with Rockefeller to be acquired.[citation needed]

Pratt and Rogers became Rockefeller's partners. Rogers, in particular, became one of Rockefeller's key men in the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. Pratt's son, Charles Millard Pratt, became secretary of Standard Oil. For many of his competitors, Rockefeller had merely to show them his books so they could see what they were up against and then make them a decent offer. If they refused his offer, he told them he would run them into bankruptcy and then cheaply buy up their assets at auction. However, he did not intend to eliminate competition entirely. In fact, his partner Pratt said of that accusation "Competitors we must have ... If we absorb them, it surely will bring up another."[52]

Instead of wanting to eliminate them, Rockefeller saw himself as the industry's savior, "an angel of mercy" absorbing the weak and making the industry as a whole stronger, more efficient, and more competitive.[64] Standard was growing horizontally and vertically. It added its own pipelines, tank cars, and home delivery network. It kept oil prices low to stave off competitors, made its products affordable to the average household, and, to increase market penetration, sometimes sold below cost. It developed over 300 oil-based products from tar to paint to petroleum jelly to chewing gum. By the end of the 1870s, Standard was refining over 90% of the oil in the U.S.[65] Rockefeller had already become a millionaire ($1 million is equivalent to $32 million[39] in 2023 dollars).[66]

He instinctively realized that orderliness would only proceed from centralized control of large aggregations of plant and capital, with the one aim of an orderly flow of products from the producer to the consumer. That orderly, economic, efficient flow is what we now, many years later, call 'vertical integration' I do not know whether Mr. Rockefeller ever used the word 'integration'. I only know he conceived the idea.

— A Standard Oil of Ohio successor of Rockefeller.[58]

In 1877, Standard clashed with Thomas A. Scott, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Standard's chief hauler. Rockefeller envisioned pipelines as an alternative transport system for oil and began a campaign to build and acquire them.[67] The railroad, seeing Standard's incursion into the transportation and pipeline fields, struck back and formed a subsidiary to buy and build oil refineries and pipelines.[68]

Standard countered, held back its shipments, and, with the help of other railroads, started a price war that dramatically reduced freight payments and caused labor unrest. Rockefeller prevailed and the railroad sold its oil interests to Standard. In the aftermath of that battle, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania indicted Rockefeller in 1879 on charges of monopolizing the oil trade, starting an avalanche of similar court proceedings in other states and making a national issue of Standard Oil's business practices.[69] Rockefeller was under great strain during the 1870s and 1880s when he was carrying out his plan of consolidation and integration and being attacked by the press. He complained that he could not stay asleep most nights. Rockefeller later commented:[58]

All the fortune that I have made has not served to compensate me for the anxiety of that period.

Monopoly

Although it always had hundreds of competitors, Standard Oil gradually gained dominance of oil refining and sales as market share in the United States through horizontal integration, ending up with about 90% of the US market.[53] In the kerosene industry, the company replaced the old distribution system with its own vertical system. It supplied kerosene by tank cars that brought the fuel to local markets, and tank wagons then delivered to retail customers, thus bypassing the existing network of wholesale jobbers.[70] Despite improving the quality and availability of kerosene products while greatly reducing their cost to the public (the price of kerosene dropped by nearly 80% over the life of the company), Standard Oil's business practices created intense controversy. Standard's most potent weapons against competitors were underselling, differential pricing, and secret transportation rebates.[71]

The firm was attacked by journalists and politicians throughout its existence, in part for these monopolistic methods, giving momentum to the antitrust movement. In 1879, the New York State Legislature's Hepburn Committee investigations into "alleged abuses" committed by the railroads uncovered the fact that Standard Oil was receiving substantial freight rebates on all of the oil it was transporting by railroad – and was crushing Standard's competitors thereby.[72] By 1880, according to the New York World, Standard Oil was "the most cruel, impudent, pitiless, and grasping monopoly that ever fastened upon a country". To critics, Rockefeller replied, "In a business so large as ours ... some things are likely to be done which we cannot approve. We correct them as soon as they come to our knowledge."[73]

At that time, many legislatures had made it difficult to incorporate in one state and operate in another. As a result, Rockefeller and his associates owned dozens of separate corporations, each of which operated in just one state; the management of the whole enterprise was rather unwieldy. In 1882, Rockefeller's lawyers created an innovative form of corporation to centralize their holdings, giving birth to the Standard Oil Trust.[74] The "trust" was a corporation of corporations, and the entity's size and wealth drew much attention. Nine trustees, including Rockefeller, ran the 41 companies in the trust.[75] The public and the press were immediately suspicious of this new legal entity, and other businesses seized upon the idea and emulated it, further inflaming public sentiment. Standard Oil had gained an aura of invincibility, always prevailing against competitors, critics, and political enemies. It had become the richest, biggest, most feared business in the world, seemingly immune to the boom and bust of the business cycle, consistently making profits year after year.[76]

The company's vast American empire included 20,000 domestic wells, 4,000 miles of pipeline, 5,000 tank cars, and over 100,000 employees.[76] Its share of world oil refining topped out above 90% but slowly dropped to about 80% for the rest of the century.[77] Despite the formation of the trust and its perceived immunity from all competition, by the 1880s Standard Oil had passed its peak of power over the world oil market. Rockefeller finally gave up his dream of controlling all the world's oil refining; he admitted later, "We realized that public sentiment would be against us if we actually refined all the oil."[77] Over time, foreign competition and new finds abroad eroded his dominance. In the early 1880s, Rockefeller created one of his most important innovations. Rather than try to influence the price of crude oil directly, Standard Oil had been exercising indirect control by altering oil storage charges to suit market conditions. Rockefeller then ordered the issuance of certificates against oil stored in its pipelines. These certificates became traded by speculators, thus creating the first oil-futures market which effectively set spot market prices from then on. The National Petroleum Exchange opened in Manhattan in late 1882 to facilitate the trading of oil futures.[78]

Although 85% of world crude production was still coming from Pennsylvania in the 1880s, oil from wells drilled in Russia and Asia began to reach the world market.[79] Robert Nobel had established his own refining enterprise in the abundant and cheaper Russian oil fields, including the region's first pipeline and the world's first oil tanker. The Paris Rothschilds jumped into the fray providing financing.[80] Additional fields were discovered in Burma and Java. Even more critical, the invention of the light bulb gradually began to erode the dominance of kerosene for illumination. Standard Oil adapted by developing a European presence, expanding into natural gas production in the U.S., and then producing gasoline for automobiles, which until then had been considered a waste product.[81]

Standard Oil moved its headquarters to New York City at 26 Broadway, and Rockefeller became a central figure in the city's business community. He bought a residence in 1884 on 54th Street near the mansions of other magnates such as William Henry Vanderbilt. Despite personal threats and constant pleas for charity, Rockefeller took the new elevated train to his downtown office daily.[82] In 1887, Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission which was tasked with enforcing equal rates for all railroad freight, but by then Standard depended more on pipeline transport.[83] More threatening to Standard's power was the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, originally used to control unions, but later central to the breakup of the Standard Oil trust. Ohio was especially vigorous in applying its state antitrust laws, and finally forced a separation of Standard Oil of Ohio from the rest of the company in 1892, the first step in the dissolution of the trust.[84]

In the 1890s, Rockefeller expanded into iron ore and ore transportation, forcing a collision with steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, and their competition became a major subject of the newspapers and cartoonists.[85] He went on a massive buying spree acquiring leases for crude oil production in Ohio, Indiana, and West Virginia, as the original Pennsylvania oil fields began to play out.[86] Amid the frenetic expansion, Rockefeller began to think of retirement. The daily management of the trust was turned over to John Dustin Archbold and Rockefeller bought a new estate, Pocantico Hills, north of New York City, turning more time to leisure activities including the new sports of bicycling and golf.[87]

Upon his ascent to the presidency, Theodore Roosevelt initiated dozens of suits under the Sherman Antitrust Act and coaxed reforms out of Congress. In 1901, U.S. Steel, then controlled by J. Pierpont Morgan, having bought Andrew Carnegie's steel assets, offered to buy Standard's iron interests as well. A deal brokered by Henry Clay Frick exchanged Standard's iron interests for U.S. Steel stock and gave Rockefeller and his son membership on the company's board of directors. In full retirement at age 63, Rockefeller earned over $58 million (~$1.65 billion in 2023) in investments in 1902.[88] One of the most effective attacks on Rockefeller and his firm was the 1904 publication of The History of the Standard Oil Company, by Ida Tarbell, a leading muckraker. She documented the company's espionage, price wars, heavy-handed marketing tactics, and courtroom evasions.[89] Although her work prompted a huge backlash against the company, Tarbell stated she was surprised at its magnitude. "I never had an animus against their size and wealth, never objected to their corporate form. I was willing that they should combine and grow as big and wealthy as they could, but only by legitimate means. But they had never played fair, and that ruined their greatness for me." Tarbell's father had been driven out of the oil business during the "South Improvement Company" affair.[citation needed] Rockefeller called her "Miss Tarbarrel" in private but held back in public saying only, "not a word about that misguided woman."[89] He began a publicity campaign to put his company and himself in a better light. Though he had long maintained a policy of active silence with the press, he decided to make himself more accessible and responded with conciliatory comments such as "capital and labor are both wild forces which require intelligent legislation to hold them in restriction." He wrote and published his memoirs beginning in 1908. Critics found his writing to be sanitized and disingenuous and thought that statements such as "the underlying, essential element of success in business are to follow the established laws of high-class dealing" seemed to be at odds with his true business methods.[90]

Rockefeller and his son continued to consolidate their oil interests as best they could until New Jersey, in 1909, changed its incorporation laws to effectively allow a re-creation of the trust in the form of a single holding company. Rockefeller retained his nominal title as president until 1911 and he kept his stock. At last in 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States found Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. By then the trust still had a 70% market share of the refined oil market but only 14% of the U.S. crude oil supply.[91] The court ruled that the trust originated in illegal monopoly practices and ordered it to be broken up into 34 new companies. These included, among many others, Continental Oil, which became Conoco, now part of ConocoPhillips; Standard of Indiana, which became Amoco, now part of BP; Standard of California, which became Chevron; Standard of New Jersey, which became Esso (and later, Exxon), now part of ExxonMobil; Standard of New York, which became Mobil, now part of ExxonMobil; and Standard of Ohio, which became Sohio, now part of BP. Pennzoil and Chevron have remained separate companies.[92]

Rockefeller, who had rarely sold shares, held over 25% of Standard's stock at the time of the breakup.[93] He and all of the other stockholders received proportionate shares in each of the 34 companies. In the aftermath, Rockefeller's control over the oil industry was somewhat reduced, but over the next 10 years the breakup proved immensely profitable for him. The companies' combined net worth rose fivefold and Rockefeller's personal wealth jumped to $900 million.[91]

Colorado Fuel and Iron

In 1902, facing cash flow problems, John Cleveland Osgood turned to George Jay Gould, a principal stockholder of the Denver and Rio Grande, for a loan.[94] Gould, via Frederick Taylor Gates, Rockefeller's financial adviser, brought John D. Rockefeller in to help finance the loan.[95] Analysis of the company's operations by John D. Rockefeller Jr. showed a need for substantially more funds which were provided in exchange for acquisition of CF&I's subsidiaries such as the Colorado and Wyoming Railway Company, the Crystal River Railroad Company, and possibly the Rocky Mountain Coal and Iron Company. Control was passed from the Iowa Group[96] to Gould and Rockefeller interests in 1903 with Gould in control and Rockefeller and Gates representing a minority interests. Osgood left the company in 1904 and devoted his efforts to operating competing coal and coke operations.[97]

Strike of 1913–14 and the Ludlow Massacre

The strike, called in September 1913 by the United Mine Workers over the issue of union representation, was against coal mine operators in Huerfano and Las Animas counties of southern Colorado, where the majority of CF&I's coal and coke production was located. The strike was fought vigorously by the coal mine operators association and its steering committee, which included Welborn, president of CF&I, a spokesman for the coal operators. Rockefeller's operative, Lamont Montgomery Bowers,[98] remained in the background. Few miners belonged to the union or participated in the strike call, but the majority honored it. Strikebreakers (called "scabs") were threatened and sometimes attacked. Both sides purchased substantial arms and ammunition. Striking miners were forced to abandon their homes in company towns and lived in tent cities erected by the union, such as the tent city at Ludlow, a railway stop north of Trinidad.[99]

Under the protection of the National Guard, some miners returned to work and some strikebreakers, imported from the eastern coalfields, joined them as Guard troops protected their movements. In February 1914, a substantial portion of the troops were withdrawn, but a large contingent remained at Ludlow. On April 20, 1914, a general fire-fight occurred between strikers and troops, which was antagonized by the troops and mine guards. The camp was burned, resulting in 15 women and children, who hid in tents at the camp, being burned to death.[99][100] Costs to both mine operators and the union were high. This incident brought unwanted national attention to Colorado.

Due to reduced demand for coal, resulting from an economic downturn, many of CF&I's coal mines never reopened and many men were thrown out of work. The union was forced to discontinue strike benefits in February 1915. There was destitution in the coalfields. With the help of funds from the Rockefeller Foundation, relief programs were organized by the Colorado Committee on Unemployment and Relief. A state agency created by Governor Carlson, offered work to unemployed miners building roads and doing other useful projects.[99]

The casualties suffered at Ludlow mobilized public opinion against the Rockefellers and the coal industry. The United States Commission on Industrial Relations conducted extensive hearings, singling out John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Rockefellers' relationship with Bowers for special attention. Bowers was relieved of duty and Wellborn restored to control in 1915, then industrial relations improved.[99]

Rockefeller denied any responsibility and minimized the seriousness of the event.[101] When testifying on the Ludlow Massacre, and asked what action he would have taken as Director, John D. Rockefeller Jr. stated, "I would have taken no action. I would have deplored the necessity which compelled the officers of the company to resort to such measures to supplement the State forces to maintain law and order." He admitted that he had made no attempt to bring the militiamen to justice.[102]

Personal life

Family

Against long-circulating speculations that his family has French roots, genealogists proved the German origin of Rockefeller and traced them to the early 17th century. Johann Peter Rockenfeller (baptized September 27, 1682, in the Protestant church of Rengsdorf) immigrated in 1723 from Altwied (today a district of Neuwied, Rhineland-Palatinate) with three children to North America. He settled in Germantown, Pennsylvania.[103][104]

The name Rockenfeller refers to the now-abandoned village of Rockenfeld in the district of Neuwied.[105]

Marriage

In 1864, Rockefeller married Laura Celestia "Cettie" Spelman (1839–1915), daughter of Harvey Buell Spelman and Lucy Henry. They had four daughters and one son together. He said later, "Her judgment was always better than mine. Without her keen advice, I would be a poor man."[44]

- Elizabeth "Bessie" Rockefeller (August 23, 1866 – November 14, 1906)

- Alice Rockefeller (July 14, 1869 – August 20, 1870)

- Alta Rockefeller (April 12, 1871 – June 21, 1962)

- Edith Rockefeller (August 31, 1872 – August 25, 1932)

- John Davison Rockefeller Jr. (January 29, 1874 – May 11, 1960)

The Rockefeller wealth, distributed as it was through a system of foundations and trusts, continued to fund family philanthropic, commercial, and, eventually, political aspirations throughout the 20th century. John Jr.'s youngest son David Rockefeller was a leading New York banker, serving for over 20 years as CEO of Chase Manhattan (now part of JPMorgan Chase). Second son Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller was Republican governor of New York and the 41st Vice President of the United States. Fourth son Winthrop Aldrich Rockefeller served as Republican Governor of Arkansas. Grandchildren Abigail Aldrich "Abby" Rockefeller and John Davison Rockefeller III became philanthropists. Grandson Laurance Spelman Rockefeller became a conservationist. Great-grandson John Davison "Jay" Rockefeller IV served from 1985 until 2015 as a Democratic Senator from West Virginia after serving as governor of West Virginia,[106] and another Winthrop served as lieutenant governor of Arkansas for a decade.

Religious views

John D. Rockefeller was born in Richford, New York, then part of the Burned-over district, a New York state region that became the site of an evangelical revival known as the Second Great Awakening. It drew masses to various Protestant churches—especially Baptist ones—and urged believers to follow such ideals as hard work, prayer, and good deeds to build "the Kingdom of God on Earth." Early in his life, he regularly went with his siblings and mother Eliza to the local Baptist church—the Erie Street Baptist Church (later the Euclid Avenue Baptist Church)—an independent Baptist church that eventually associated with the Northern Baptist Convention (1907–1950; now part of the modern American Baptist Churches USA).[citation needed]

His mother was deeply religious and disciplined, and had a major influence on him in religious matters. During church service, his mother would urge him to contribute his few pennies to the congregation. Rockefeller associated the church with charity. A Baptist preacher once encouraged him to "make as much money as he could, and then give away as much as he could".[107] Later in his life, Rockefeller recalled: "It was at this moment, that the financial plan of my life was formed". Money making was considered by him a "God-given gift".[107]

A devout Northern Baptist, Rockefeller would read the Bible daily, attend prayer meetings twice a week and led his own Bible study with his wife. Burton Folsom Jr. has noted:

[H]e sometimes gave tens of thousands of dollars to Christian groups, while, at the same time, he was trying to borrow over a million dollars to expand his business. His philosophy of giving was founded upon biblical principles. He truly believed in the biblical principle found in Luke 6:38, "Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap. For with the measure you use, it will be measured to you."[107]

Rockefeller would support Baptist missionary activity, fund universities, and deeply engage in religious activities at his Cleveland, Ohio, church. While traveling the South, he would donate large sums of money to churches belonging to the Southern Baptist Convention, various Black churches, and other Christian denominations. He paid toward the freedom of two slaves[108] and donated to a Roman Catholic orphanage. As he grew rich, his donations became more generous, especially to his church in Cleveland. Believed to be obsolescent, the church was demolished in 1925, and replaced with a new building.[107]

Philanthropy

Rockefeller's charitable giving began with his first job as a clerk at age 16, when he gave six percent of his earnings to charity, as recorded in his personal ledger. By the time he was twenty, his charity exceeded ten percent of his income. Much of his giving was church-related.[109] His church was later affiliated with the Northern Baptist Convention, which formed from American Baptists in the North with ties to their historic missions to establish schools and colleges for freedmen in the South after the American Civil War. Rockefeller attended Baptist churches every Sunday; when traveling he would often attend services at African-American Baptist congregations, leaving a substantial donation.[109] As Rockefeller's wealth grew, so did his giving, primarily to educational and public health causes, but also for basic science and the arts. He was advised primarily by Frederick Taylor Gates[110] after 1891,[111] and, after 1897, also by his son.

Rockefeller believed in the Efficiency Movement, arguing that: "To help an inefficient, ill-located, unnecessary school is a waste ... it is highly probable that enough money has been squandered on unwise educational projects to have built up a national system of higher education adequate to our needs, if the money had been properly directed to that end."[112]

Rockefeller and his advisers invented the conditional grant, which required the recipient to "root the institution in the affections of as many people as possible who, as contributors, become personally concerned, and thereafter may be counted on to give to the institution their watchful interest and cooperation".[113]

In 1884, Rockefeller provided major funding for Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary in Atlanta for African-American women, which became Spelman College.[114] His wife Laura Spelman Rockefeller, was dedicated to civil rights and equality for women.[115] John and Laura donated money and supported the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary whose mission was in line with their faith based beliefs. Today known as Spelman College, the school is an all women Historically Black College or University in Atlanta, Georgia, named after Laura's family. The Spelman Family, Rockefeller's in-laws, along with John Rockefeller were ardent abolitionists before the Civil War and were dedicated to supporting the Underground Railroad.[115] John Rockefeller was impressed by the vision of the school and removed the debt from the school. The oldest existing building on Spelman's campus, Rockefeller Hall, is named after him.[116] Rockefeller also gave considerable donations to Denison University[117] and other Baptist colleges.

Rockefeller gave $80 million (~$2.41 billion in 2023) to the University of Chicago[118] under William Rainey Harper, turning a small Baptist college into a world-class institution by 1900. He would describe the University of Chicago as "the best investment I ever made." He also gave a grant to the American Baptist Missionaries foreign mission board, the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society in establishing Central Philippine University, the first Baptist and second American university in Asia, in 1905 in the heavily Catholic Philippines.[119][120][16][14][15]

Rockefeller's General Education Board, founded in 1903,[121] was established to promote education at all levels everywhere in the country.[122] In keeping with the historic missions of the Baptists, it was especially active in supporting black schools in the South.[122] Rockefeller also provided financial support to such established eastern institutions as Yale, Harvard, Columbia, Brown, Bryn Mawr, Wellesley and Vassar. On Gates' advice, Rockefeller became one of the first great benefactors of medical science. In 1901, he founded the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research[121] in New York City. It changed its name to Rockefeller University in 1965, after expanding its mission to include graduate education.[123] It claims a connection to 23 Nobel laureates.[124] He founded the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission in 1909,[121] an organization that eventually eradicated the hookworm disease,[125] which had long plagued rural areas of the American South. His General Education Board made a dramatic impact by funding the recommendations of the Flexner Report of 1910.[citation needed] The study, an excerpt of which was published in The Atlantic,[13] had been undertaken by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[citation needed]

Rockefeller created the Rockefeller Foundation in 1913[126] to continue and expand the scope of the work of the Sanitary Commission,[121] which was closed in 1915.[127] He gave $182 million to the foundation,[114] which focused on public health, medical training, and the arts. It endowed Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health,[121] the first of its kind.[128] It also built the Peking Union Medical College in China into a notable institution.[117] The foundation helped in World War I war relief,[129] and it employed William Lyon Mackenzie King of Canada to study industrial relations.[130]

In the 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation funded a hookworm eradication campaign through the International Health Division. This campaign used a combination of politics and science, along with collaboration between healthcare workers and government officials to accomplish its goals.[131]

Rockefeller's fourth main philanthropy, the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation, was created in 1918.[132] Through this, he supported work in the social studies; this was later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation. In total Rockefeller donated about $530 million.[133]

Rockefeller became well known in his later life for the practice of giving dimes to adults and nickels to children wherever he went. He even gave dimes as a playful gesture to wealthy men, such as tire mogul Harvey Firestone.[134]

Rockefeller supported the passage of the 18th Amendment, which banned alcohol in the United States. He wrote in a letter to Nicholas Murray Butler on June 6, 1932, that neither Rockefeller nor his parents or his father's father and mother's mother drank alcohol. In the same letter, Rockefeller writes that he has "always stood for whatever measure seemed at the time to give promise of promoting temperance." He believed that measure to be prohibition, as he and his father donated $350,000 to "all branches of the Anti-Saloon League, Federal and State." But by 1932, Rockefeller felt disillusioned by prohibition because of its failure to discourage drinking and alcoholism. He supported the incorporation of repealing the 18th amendment into the Republican party platform.[135]

Florida home

Henry Morrison Flagler, one of the co-founders of Standard Oil along with Rockefeller, bought the Ormond Hotel in 1890, located in Ormond Beach, Florida, two years after it opened. Flagler expanded it to accommodate 600 guests and the hotel soon became one in a series of Gilded Age hotels catering to passengers aboard Flagler's Florida East Coast Railway. One of Flagler's guests at the Ormond Hotel was his former business partner John D. Rockefeller, who first stayed at the hotel in 1914. Rockefeller liked the Ormond Beach area so much that after four seasons at the hotel, he bought an estate in Ormond Beach called The Casements.[136][137] It would be Rockefeller's winter home during the latter part of his life. Sold by his heirs in 1939,[138] it was purchased by the city in 1974 and now serves as a cultural center and is the community's best-known historical structure.[139]

Illnesses and death

In his 50s Rockefeller suffered from moderate depression and digestive troubles; during a stressful period in the 1890s he developed alopecia, the loss of some or all body hair.[140] By 1901 he began wearing toupées and by 1902, his mustache disappeared. His hair never grew back, but other health complaints subsided as he lightened his workload.[141]

Rockefeller died of arteriosclerosis on May 23, 1937, less than two months shy of his 98th birthday,[142] at "The Casements", his home in Ormond Beach, Florida. He was buried in Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.[143]

Legacy

Rockefeller had a long and controversial career in the oil industry followed by a long career in philanthropy. His image is an amalgam of all of these experiences and the many ways he was viewed by his contemporaries. These contemporaries include his former competitors, many of whom were driven to ruin, but many others of whom sold out at a profit (or a profitable stake in Standard Oil, as Rockefeller often offered his shares as payment for a business), and quite a few of whom became very wealthy as managers as well as owners in Standard Oil. They include politicians and writers, some of whom served Rockefeller's interests, and some of whom built their careers by fighting Rockefeller and the "robber barons".

Biographer Allan Nevins, answering Rockefeller's enemies, concluded:

The rise of the Standard Oil men to great wealth was not from poverty. It was not meteor-like, but accomplished over a quarter of a century by courageous venturing in a field so risky that most large capitalists avoided it, by arduous labors, and by more sagacious and farsighted planning than had been applied to any other American industry. The oil fortunes of 1894 were not larger than steel fortunes, banking fortunes, and railroad fortunes made in similar periods. But it is the assertion that the Standard magnates gained their wealth by appropriating "the property of others" that most challenges our attention. We have abundant evidence that Rockefeller's consistent policy was to offer fair terms to competitors and to buy them out, for cash, stock, or both, at fair appraisals; we have the statement of one impartial historian that Rockefeller was decidedly "more humane toward competitors" than Carnegie; we have the conclusion of another that his wealth was "the least tainted of all the great fortunes of his day."[144]

Hostile critics often portrayed Rockefeller as a villain with a suite of bad traits—ruthless, unscrupulous and greedy—and as a bully who connived his cruel path to dominance. Economic historian Robert Whaples warns against ignoring the secrets of his business success:

[R]elentless cost cutting and efficiency improvements, boldness in betting on the long-term prospects of the industry while others were willing to take quick profits, and impressive abilities to spot and reward talent, delegate tasks, and manage a growing empire.[145]

Biographer Ron Chernow wrote of Rockefeller:[146]

What makes him problematic—and why he continues to inspire ambivalent reactions—is that his good side was every bit as good as his bad side was bad. Seldom has history produced such a contradictory figure.[147]

Wealth

Rockefeller is largely remembered simply for the raw size of his wealth. In 1902, an audit showed Rockefeller was worth about $200 million—compared to the total national GDP of $24 billion then.[148]

His wealth continued to grow significantly (in line with U.S. economic growth) as the demand for gasoline soared, eventually reaching about $900 million on the eve of the First World War, including significant interests in banking, shipping, mining, railroads, and other industries. His personal wealth was 900 million in 1913 worth 23.5 billion dollars adjusted for inflation in 2020.[149] According to his New York Times obituary, "it was estimated after Mr. Rockefeller retired from business that he had accumulated close to $1,500,000,000 out of the earnings of the Standard Oil trust and out of his other investments. This was probably the greatest amount of wealth that any private citizen had ever been able to accumulate by his own efforts."[150] By the time of his death in 1937, Rockefeller's remaining fortune, largely tied up in permanent family trusts, was estimated at $1.4 billion, while the total national GDP was $92 billion.[1] According to some methods of wealth calculation, Rockefeller's net worth over the last decades of his life would easily place him as the wealthiest known person in recent history. As a percentage of the United States' GDP, no other American fortune—including those of Bill Gates or Sam Walton—would even come close.[citation needed]

Rockefeller, aged 86, wrote the following words to sum up his life:[151]

I was early taught to work as well as play,

My life has been one long, happy holiday;

Full of work and full of play—

I dropped the worry on the way—

And God was good to me everyday.

See also

- Allegheny Transportation Company

- Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railway

- Ivy Lee

- List of German Americans

- Rockefeller's Mesabi Range Interests

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ a b c Hargreaves, Steve. "The Richest Americans". CNN. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- ^ "The Wealthiest Americans Ever". The New York Times. July 15, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ a b "John D. Rockefeller: The Richest Man in the World". Harvard Business School. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Housel, Morgan. "Who will be the world's first trillionaire?". USA Today. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ "Top 10 Richest Men of All Time". AskMen.com. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ "The Rockefellers". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ Nicholas, Tom; Fouka, Vasiliki. "John D. Rockefeller: The Richest Man in the World". hbs.edu. President & Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ US Gross Domestic Product 1913–1939 Stuck on Stupid: U.S. Economy http://www.usstuckonstupid.com/sos_charts.php#gdp Archived June 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daniel Gross (July 2, 2006). "Giving It Away, Then and Now – The New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Fosdick 1989, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Eradicating Hookworm". Rockefeller Archive Center. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Hookworm: Exporting a Campaign". Rockefeller Archive Center. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ a b GRITZ, JENNIE ROTHENBERG (June 23, 2011). "The Man Who Invented Medical School". The Atlantic.

- ^ a b A walk through the beautiful Central. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Weekly Centralian Link (June 15, 2018) – CPU holds Faculty and Staff Conference 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Facts about Central. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Martin, Albro (1999), "John D. Rockefeller", Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 23

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 52.

- ^ Hofstadter 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Schultz, Duane P.; Schultz, Sydney Ellen, A History of Modern Psychology, p. 128

- ^ a b Newton, David E. (2013). World Energy Crisis: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-61069-147-5.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 7. "A prudent, straitlaced Baptist of Scotch-Irish descent, deeply attached to his daughter, John Davison must have sensed the world of trouble that awaited Eliza..."

- ^ Flynn, John T. (2007). God's Gold. Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-61016-411-5.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Chernow 1998, Chapter one: "The Flimflam Man" via New York Times.

- ^ Chernow 1998, pp. 43, 50, 235.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 14.

- ^ "Business profile: From turkeys to oil... the rise of John D Rockefeller". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Manchester, William (October 6, 1974). "The founding grandfather". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "The Philanthropists: John D. Rockefeller – Tim Challies". October 13, 2013.

- ^ Coffey, Ellen Greenman; Shuker, Nancy (1989), John D. Rockefeller, empire builder, Silver Burdett, pp. 18, 30

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 40.

- ^ "John D. Rockefeller | Biography, Facts, & Death". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Hawke 1980, pp. 23, 24.

- ^ Hawke 1980, p. 22.

- ^ a b c 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Stevens, Mark (2008). Rich is a Religion: Breaking the Timeless Code to Wealth. John Wiley & Sons. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-470-25287-1.

- ^ a b John D., A Portrait in Oils, John. K. Winkler, The Vanguard Press, New York, June, 1929, p. 50-56

- ^ a b Ron Chernow (2004) Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.-Vintage, New York, p. 69-75-83

- ^ Hawke 1980, p. 26.

- ^ a b Segall 2001, p. 25.

- ^ Hawke 1980, pp. 29, 36.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Chernow 1998, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Folsom 2003, pp. 84–85, "Chapter 5: John D. Rockefeller and the Oil Industry".

- ^ Williamson & Daum 1959, pp. 82–194.

- ^ Hawke 1980, pp. 31, 32.

- ^ Chernow 1998, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c Nevins 1940, pp. 183–185, 197–198.

- ^ a b Folsom 2003, "Chapter 5: John D. Rockefeller and the Oil Industry".

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 32.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 32, 35.

- ^ "People & Events: John D. Rockefeller Senior, 1839–1937". PBS. Archived from the original on December 16, 2000. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ "Our History". ExxonMobil. Archived from the original on November 12, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c Yergin 1991, p. [page needed].

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 132.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Udo Hielscher: Historische amerikanische Aktien, p. 68 – 74, ISBN 3921722063

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 253.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 258.

- ^ "Proceedings of the Special Committee on Railroads, Appointed under a resolution of the Assembly to investigate alleged abuses in the Management of Railroads chartered by the State of New York (Vol. I, 1879)". Internet Archive. New York State Legislature. 1879. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

Resolved, That a special Committee of five [afterwards increased to nine] persons be appointed, with power to send for persons and papers, and to employ a stenographer, whose duty it shall be to investigate the abuses alleged to exist in the management of the railroads chartered by this State, and to inquire into and report concerning their powers, contracts and obligations; said Committee to take testimony in the city of New York, and such other places as they may deem necessary, and to report to the Legislature, either at the present or the next session, by bill or otherwise, what, if any, legislation is necessary to protect and extend the commercial and industrial interests of the State. Composed of Messrs. HEPBURN, HUSTED, DUGUID, LOW, GRADY, NOYES, WADSWORTH, TERRY and BAKER, met at the Capitol in the City of Albany on Wednesday March 26th, 1879, at 3 o'clock P. M., and was called to order by the Chairman.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 60.

- ^ "John D. Rockefeller". history.com. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 61.

- ^ a b Chernow 1998, p. 249.

- ^ a b Segall 2001, p. 67.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 259.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 242.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 246.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 68.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Rockefeller 1984, p. 48.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 69.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 287.

- ^ Segall 2001, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 84.

- ^ a b Segall 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 91.

- ^ a b Segall 2001, p. 93.

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 112.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 333.

- ^ Scamehorn 1992a, p. 17.

- ^ Scamehorn 1992a, p. 18.

- ^ Scamehorn 1992a, p. 19.

- ^ Scamehorn 1992a, p. 20.

- ^ "Lamont Montgomery Bowers". Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Scamehorn 1992c.

- ^ "Militia slaughters strikers at Ludlow, Colorado". History.com. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "The Ludlow Massacre". PBS. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Rockefeller Says He Tries To Be Fair". The New York Times. May 21, 1915.

- ^ Chernow 1998, pp. 3, 10.

- ^ Scheiffarth, Engelbert (1969), "Der New Yorker Gouverneur Nelson A. Rockefeller und die Rockefeller im Neuwieder Raum", Genealogisches Jahrbuch (in German), 9: 16–41

- ^ "Rockefeller". Dictionary of American Family Names (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 9780195081374. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Rockefeller, John Davison IV (Jay)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Rockefellers documentary[full citation needed]

- ^ Segall 2001, p. 24.

- ^ a b Chernow 1998, pp. 50, 235.

- ^ Coon, Horace (1990). Money to burn: great American foundations and their money. Transaction Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 0-88738-334-3.

- ^ Creager, Angela (2002). The life of a virus: tobacco mosaïc virus as an experimental model, 1930–1965. The University of Chicago Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-226-12025-2.

- ^ Rockefeller 1984, p. 69.

- ^ Rockefeller 1984, p. 183.

- ^ a b Weir, Robert (2007). Class in America: Q-Z. Greenwood Press. p. 713. ISBN 978-0-313-34245-5.

- ^ a b Laughlin, Rosemary. 2001. "John D. Rockefeller: Oil Baron and Philanthropist." Biography Reference Center, EBSCO

- ^ Miller-Bernal, Leslie (2006). Challenged by coeducation: women's colleges since the 1960s. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-8265-1542-8.

- ^ a b Fosdick 1989, pp. 5, 88.

- ^ Dobell, Byron (1985). A Sense of history: the best writing from the pages of American heritage. American Heritage Press. p. 457. ISBN 0-8281-1175-8.

- ^ "WO Valentine", The Centennial Echo (brief biography), Central Philippine University, 2004, archived from the original on October 31, 2003, retrieved January 26, 2013

- ^ Founder's Day Celebration, Central Philippine University, October 1, 2005, archived from the original on July 22, 2011, retrieved January 16, 2013

- ^ a b c d e Brison, Jeffrey David (2005). Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Canada: American philanthropy and the arts and the arts and letters in Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 27, 31, 62. ISBN 0-7735-2868-7.

- ^ a b Jones-Wilson, Faustine Childress (1996). Encyclopedia of African-American education. Greenwood Press. p. 184. ISBN 0-313-28931-X.

- ^ Unger, Harlow (2007). Encyclopedia of American Education: A to E. Infobase Publishing. p. 949. ISBN 978-0-8160-6887-6.

- ^ Beaver, Robyn (2008). KlingStubbins: palimpsest. Images Publishing. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-86470-295-8.

- ^ Hotez, Peter (2008). Forgotten people, forgotten diseases: the neglected tropical diseases and their impact on global health and development. ASM Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55581-440-3.

- ^ Klein 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Sealander, Judith (1997). Private wealth & public life: foundation philanthropy and the reshaping of American soclial policy from the Progressive Era to the New Deal. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-8018-5460-1.

- ^ Freeman, A.W. (July 1922). The Rotarian. p. 20.

- ^ Schneider, William Howard (1922). Rockefeller philanthropy and modern biomedicine: international initiatives from World War I to Cold War. Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-253-34151-5.

- ^ Prewitt, Kenneth; Dogan, Mettei; Heydmann, Steven; Toepler, Stefan (2006). The legitimacy of philanthropic foundations: United States and European perspectives. Russell Sage Foundation. p. 68. ISBN 0-87154-696-5.

- ^ Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Solorzano, Armando (1999). "Public health policy paradoxes: science and politics in the Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (9): 1197–1213. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00160-4. PMID 10501641.

- ^ "Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Foundation". Famento. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ The Philanthropy Hall of Fame, John D. Rockefeller Sr. profile, philanthropyroundtable.org; accessed October 21, 2016.

- ^ Chernow 1998, pp. 613–14.

- ^ "Text of Rockefeller's Letter to Dr. Butler". The New York Times. June 7, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Stasz 2000, p. 209.

- ^ Chernow 1998, p. 610.

- ^ "History". Ormond Beach. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "History of the House and The Guild". The Casements. n.d. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ "John D. Rockefeller Sr. and family timeline". PBS. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ "John D Rockefeller:Infinitely Ruthless, Profoundly Charitable". HistoryAccess.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ^ Carmichael, Evan. "The Richest Man In History: Rockefeller is Born". Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ "Old Home Visited By Rockefellers". The Plain Dealer. May 28, 1937. p. 4.

- ^ Latham 1949, p. 104.

- ^ Robert Whaples, "Review of Doran, Breaking Rockefeller: The Incredible Story of the Ambitious Rivals Who Toppled an Oil Empire EH.Net (July 2016)

- ^ Visser, Wayne (2011). The Age of Responsibility: CSR 2.0 and the New DNA of Business. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119973386. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ Chernow 1998.

- ^ "US GDP". Measuring Worth. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

- ^ United States Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics – historical inflation calculator

- ^ "Financier's Fortune in Oil Amassed in Industrial Era of 'Rugged Individualism'". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ "Rockefeller" (PDF). ANBHF. Retrieved September 11, 2010.

General bibliography

- Bringhurst, Bruce (May 10, 1979). Antitrust and the Oil Monopoly: The Standard Oil Cases, 1890–1911 (Contributions in Legal Studies). Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-20642-9.

- Chernow, Ron (1998). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-43808-3. Online via Internet Archive

- Collier, Peter; Horowitz, David (1976). The Rockefellers: An American Dynasty. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 9780030083716.

- Ernst, Joseph W., editor. "Dear Father"/"Dear Son": Correspondence of John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. New York: Fordham University Press, with the Rockefeller Archive Center, 1994.

- Folsom, Burton W. Jr. (2003). The Myth of the Robber Barons. New York: Young America.

- Fosdick, Raymond B. (1989). The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation (reprint ed.). New York: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-248-7.

- Gates, Frederick Taylor. Chapters in My Life. New York: The Free Press, 1977.

- Giddens, Paul H. Standard Oil Company (Companies and men). New York: Ayer Co. Publishing, 1976.

- Goulder, Grace. John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years. Western Reserve Historical Society, 1972.

- Harr, John Ensor; Johnson, Peter J. (1988). The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ———; Johnson, Peter J. (1992). The Rockefeller Conscience: An American Family in Public and in Private. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980), John D: The Founding Father of the Rockefellers, New York: Harper and Row

- Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. History of Standard Oil Company (New Jersey: Pioneering in Big Business). New York: Ayer Co., reprint, 1987.

- Hofstadter, Richard (1992) [1944]. Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-5503-8.

- Jonas, Gerald. The Circuit Riders: Rockefeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1989.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons. London: Harcourt, 1962.

- Kert, Bernice. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller: The Woman in the Family. New York: Random House, 1993.

- Klein, Henry H. (2003) [1921]. Dynastic America and Those Who Own It. New York: Kessinger.

- Klein, Henry (2005) [1921]. Dynastic America and Those Who Own It. Cosimo. ISBN 1-59605-671-1.

- Knowlton, Evelyn H. and George S. Gibb. History of Standard Oil Company: Resurgent Years 1956.

- Latham, Earl, ed. (1949). John D. Rockefeller: Robber Baron or Industrial Statesman?.

- Manchester, William. A Rockefeller Family Portrait: From John D. to Nelson. New York: Little, Brown, 1958.

- Morris, Charles R. The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Owl Books, reprint, 2006.

- Nevins, Allan (1940). John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise. Favorable scholarly biography

- Nevins, Allan (1953). Study in Power: John D. Rockefeller, Industrialist and Philanthropist. 2 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Pyle, Tom, as told to Beth Day. Pocantico: Fifty Years on the Rockefeller Domain. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1964.

- Roberts, Ann Rockefeller. The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1998.

- Rockefeller, John D. (1984) [1909]. Random Reminiscences of Men and Events. New York: Sleepy Hollow Press and Rockefeller Archive Center.

- Public Diary of John D. Rockefeller, now found in the Cleveland Western Historical Society

- Rose, Kenneth W.; Stapleton, Darwin H. (1992). "Toward a 'Universal Heritage': Education and the Development of Rockefeller Philanthropy, 1884–1913". Teachers College Record. 93 (3): 536–55. doi:10.1177/016146819209300315. ISSN 0161-4681. S2CID 151797425.

- Sampson, Anthony (1975). The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Made. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Scamehorn, H. Lee (1992a). "Chapter 1: The Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, 1892–1903". Mill and Mine: The CF&I in the Twentieth Century. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4214-2.

- Scamehorn, H. Lee (1992c). "Chapter 3: The Coal Miners' Strike of 1913–1914". Mill and Mine: The CF&I in the Twentieth Century. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 38–55. ISBN 978-0-8032-4214-2.

- Segall, Grant (February 8, 2001). John D. Rockefeller: Anointed With Oil. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19512147-6. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- Stasz, Clarice (2000). The Rockefeller Women: Dynasty of Piety, Privacy, and Service. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-58348-856-0.

- Tarbell, Ida M. (1963) [1904]. The History of the Standard Oil Company. 2 vols. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

- Williamson, Harold F.; Daum, Arnold R. (1959). The American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Illumination. (vol. 1); also vol 2, Williamson, Harold F.; Daum, Arnold R. (1964). American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Energy.

- Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-1012-6.

External links

- John D. Rockefeller Biography

- Works by John D. Rockefeller at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John D. Rockefeller at Internet Archive

- Works by John D. Rockefeller at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)