Contents

In November 1902, a white mob from Sullivan and Knox counties lynched James Dillard, a young Black man from Indianapolis. Dillard's death resulted in a lengthy legal battle over Indiana's 1899 anti-lynching law.

Life

James Dillard and his mother moved from Tennessee to Indianapolis in 1895.[1] In Indianapolis, Dillard worked a variety of jobs including being a porter at the Columbia Club and at Young’s Billiard Room.[2] At the time of his death, Dillard was in his twenties. He had left Indianapolis in the spring of 1901 and it is unknown why he was in Sullivan County.[1]

Lynching

In November 1902, residents in Sullivan and Knox counties accused James Dillard of assaulting two white women, the wives of Milton Davis and John Lemon.[2][3] On November 19, police apprehended Dillard in Lawrenceville, Illinois, shooting him three times in the process.[2][4] After police arrested Dillard, they transported him to Sullivan.[4] While being transported, a mob of approximately 50 local farmers gathered in the area, causing the Sullivan County sheriff, John S. Dudley, to invoke Indiana's 1899 anti-lynching law by requesting that Governor Winfield Durbin send in militia.[4][5][6] The militia was sent from Vincennes, many miles south of the mob and too far away to make it before Dudley conceded Dillard to the mob.[4]

Once the mob kidnapped Dillard, they decided to have his accusers identify him. They took him to the houses of both Davis in Sullivan County and Lemon in Knox County to be identified. After leaving the second house, the mob decided to abruptly end Dillard's life by lynching him on a telegraph pole near Oaktown, Indiana on November 20.[2][6]

Aftermath

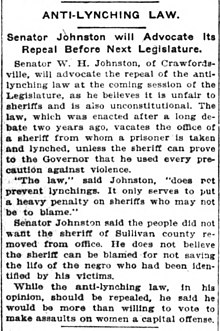

The lynching of James Dillard is one of the first events in which a governor enacted the 1899 Indiana anti-lynching law. This law intended to prevent lynchings by requiring sheriffs to protect prisoners from mob kidnappings and request militia back-up from the governor when lynchings were threatened. The punishment for noncompliance would be the sheriff's removal from office.[5]

In response to the lynching of James Dillard, Governor Durbin enforced this 1899 law, removing Sheriff Dudley from office. However, after a lengthy legal battle in which Dudley, townspeople, and other government officials fought against Durbin's decision, Dudley remained in office, demonstrating the difficulty of enforcing this law.[4][5][7] The lynching of James Dillard is cited as the last well-known lynching in Indiana before the 1930 lynching in Marion.[8]

References

- ^ a b "Dillard's Mother Found". The Indianapolis News. Indianapolis, IN. November 21, 1902. Retrieved April 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Hanged to a Pole". Indianapolis Journal. Vol. 52, no. 325. Indianapolis, IN. November 21, 1902.

- ^ Sdunzik, Jennifer (2019). "Indiana". In Reid-Merritt, Patricia (ed.). A State-by-State History of Race and Racism in the United States. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. pp. 283–299.

- ^ a b c d e Trigg, Lisa (May 3, 2018). "One lynching each recorded in Sullivan, Vigo histories". Tribune-Star. Terre Haute, IN.

- ^ a b c Madison, James H. (2001). A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America. New York: Palgrave.

- ^ a b McCormick, Mike (November 17, 2002). "A lynching, fightin' women, and a visit from Eugene V. Debs mark 100 years ago". Terre Haute Tribune Star. Terre Haute, IN.

- ^ Cutler, James Elbert (1905). Lynch-law: An Investigation Into the History of Lynching in the United States. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-557-35340-8.

- ^ Poletika, Nicole (May 15, 2018). "Strange Fruit: The 1930 Marion Lynching and the Woman Who Tried to Prevent It". Indiana History Blog. Indiana Historical Bureau.